Abstract

Objective

We aimed to epidemiologically assess rubella herd immunity as a function of time, age and gender in Japan, with reference to the recent 2012–2014 rubella epidemic.

Design

This study is a retrospective seroepidemiological analysis.

Main outcome measures

The susceptible fraction of the population was examined as a function of age and time. The age at infection was assessed using reported case data.

Results

Whereas 30 years ago rubella cases were seen only among children, the median (25–75th centiles) age of cases in 2014 was elevated to 32.0 (17.0–42.0) years among males and 27.0 (7.0–37.0) years among females. Susceptible pockets among male birth cohorts 1989–1993 and 1974–1978 were identified, with seropositive proportions of 70.0% and 68.0%, respectively. The majority of female age groups had greater seropositive proportions than the herd immunity threshold, with a minor susceptible pocket for those born from 1989 to 1993 (78.3% seropositive). The age-standardised seronegative proportion decreased to 18.3% (95% CI 16.8% to 19.8%) among males and 15.6% (95% CI 10.0% to 21.2%) among females in 2013, and the immune fraction was not sufficiently below the herd immunity threshold. While the number of live births born to susceptible mothers in 1983 was estimated at 171 876 across Japan, in 2013 it was reduced to 23 698.

Conclusions

An elevated age at rubella virus infection and the presence of susceptible pockets among adults were observed in Japan. Although, overall, the absolute number of rubella cases has steadily declined in Japan, the elevated age of rubella cases, along with increased numbers of susceptible adults, contributed to the observation of as many as 45 congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) cases, which calls for supplementary vaccination among susceptible adults. Assessing herd immunity is considered essential for routinely monitoring the risk of future rubella epidemics and CRS cases.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study consists of an explicit assessment of herd immunity using multitudes of data sets, including seroepidemiological survey data.

It contains an analysis of epidemiological data over a long time period, which enables us to capture the elevated age at rubella infection and identify susceptible pockets of the population.

It uses epidemiological metrics that measure the standardised seronegative proportion of the entire population as well as among pregnant women.

Only a retrospective analysis was conducted, and an optimal vaccination policy has yet to be explored.

Background

Although rubella is a vaccine-preventable disease,1 2 Japan has yet to be successful in bringing this disease under full control. When rubella vaccination was introduced in 1976, Japan initially focused on women aged from 12 to 15 years as vaccinees, aiming to individually protect women who were at risk of having a fetus with congenital rubella infection, which may lead to congenital rubella syndrome (CRS).3 4 In 1995, the vaccination policy shifted, targeting both genders aged from 12 to 90 months (typically from 12 to 36 months) to elevate and maintain herd immunity. Although Japan is considered to be on its way to establishing sufficient herd immunity through vaccination, the country has recently experienced two major rubella epidemics, in 2004 and 2012–2014, involving 4248 and 12 614 reported rubella cases, respectively, and yielding 45 CRS cases in the most recent epidemic.5 6 Despite the implementation of supplementary vaccination after the 2004 epidemic, which was conducted among women of childbearing age as well as among their family members, the most recent epidemic was not prevented and involved a large number of adult cases.7 8

The age at infection with rubella virus is elevated by vaccination, but if the vaccination coverage is insufficient to prevent major epidemics, the insufficient vaccination programme could be responsible for a tragic increase in the number of CRS cases due to an increased risk of infection among pregnant women.9 Thus, once a country decides to aim to eliminate rubella, it is critical to ensure a high level of population immunity, among males and females.10 The potential consequence of the 1995 change in the Japanese vaccination policy may be that different birth cohorts have different levels of immunity against rubella.5 11 In fact, there were two notable characteristics of the rubella cases from the 2012 to 2014 epidemic: (1) 72% of the cases were adults7 and (2) the cases were concentrated in males aged 20–39 years (68%).10 An explicit assessment of the herd immunity is crucial for planning future ways to control the spread of this disease.12–18 The present study aimed to statistically analyse the transmission dynamics of rubella in Japan, with a particular emphasis on the most recent major epidemic from 2012 to 2014, and to assess the population level immunity over age and time.

Methods

Epidemiological data

To elucidate the epidemiological dynamics of rubella in Japan, we analysed three pieces of information: (1) reported cases of rubella and CRS, (2) seroepidemiological data and (3) vaccination coverage. The seroepidemiological data and vaccination coverage were investigated to assess herd immunity.12 19 20 The rubella and CRS data rest on the reporting of cases to the National Epidemiological Surveillance for Infectious Diseases (NESID), which were collected according to the Communicable Disease Prevention Law until 1998 and according to the Infectious Diseases Control Law thereafter.5 6 From 1982 to 2007, a sentinel surveillance of rubella cases was conducted, which received notifications from approximately 3000 sentinel paediatric clinics.10 Reporting of CRS cases first started in 1999; in 2008, a revision was made to the surveillance, requiring all diagnosed rubella and CRS cases to be reported.4 10

The seroepidemiological data were derived from the National Epidemiological Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (NESVPD).21 This serial cross-sectional serological survey, quantifying haemagglutination inhibition (HI) titres, has been implemented every year from July to September, non-randomly selecting the geographical area from which it draws its participants. The serum was collected by region from >5400 participants of all ages, recruiting participants from those who visited a prefectural medical facility or public health centre.22 The present study takes into consideration the survey data from every 5 years since 1983 to investigate the longitudinal trend of age at rubella infection, standardised seronegative proportion, and the number of live births that were born to seronegative mothers and considered to be at risk of CRS.

The vaccination coverage data were retrieved from the immunisation records of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.23 Vaccination coverage was calculated as the ratio of the annual number of vaccinations to the population size of an age-group that newly entered the participant age-group of vaccination, and this was overlaid with data from the reported rubella cases.

Statistical analysis

Time-dependent and age-dependent epidemiological dynamics of confirmed rubella cases from 1982 to 2014 were examined along with the changes in the vaccination coverage over this time period. Additionally, the reported rubella and CRS cases from 2012 to 2014 were examined to understand the comparative magnitude of the recent epidemic. The age and gender specificity of the recent epidemic were also examined.

Using serial cross-sectional seroepidemiological survey data from 2003, 2008, and 2013, the distributions of HI titre by age and gender were examined. Owing to the small sample size for each age, discrete age grouping was carried out over every 5 years. For this reason, the seroprevalence was compared by age and time as well as by birth year cohort. Seroconversion, following the convention in Japan (corresponding to results of ≥7.3 IU/mL from ELISA), was defined as an HI titre ≥32.24 The basic reproduction number, R0, acknowledged as the average number of secondary cases generated by a single primary case, was estimated at 6.1 for rubella using an age-structured realistic model.25 The herd immunity threshold against rubella was calculated by 1−(1/R0), and came to 83.6%.25 While we set the baseline levels of seropositivity and herd immunity by using the threshold described above, a sensitivity analysis was carried out using alternative values, that is, a conventionally accepted cut-off value of HI titre ≥8 and a seroprevalence of 94.0%, as adopted elsewhere.26 27 Adhering to published studies on herd immunity assessment, we also analysed the true prevalence with the assumption that the sensitivity and specificity of the serological testing were each 97%.26 27

The time-dependent elevation of age at rubella infection was examined using the reported case data. The age distribution of reported cases from 1982 to 2014 was analysed. A χ2 trend test was implemented to detect if there was an elevation in the age at infection from 1982 to 2014.

Evaluation metrics

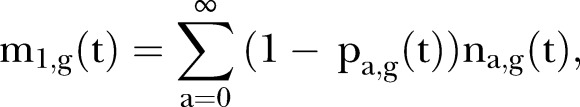

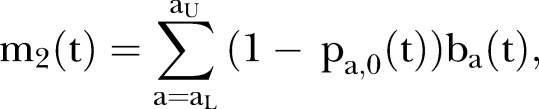

To assess herd immunity at the population level, we employed two evaluation metrics. These metrics focused on the seroprevalence data (and did not use vaccination coverage) because a substantial fraction of immune individuals, especially adults, acquired their immunity through a natural infection rather than through vaccination. First, we calculated the age-standardised seroprevalence, m1,g(t), at calendar time t and in gender g (g=0 for females or 1 for males), as

|

where pa,g(t) is the observed seropositive proportion and na,g(t) is the relative population size at time t and gender g of those aged a years. This metric is interpreted as the age-standardised seronegative proportion. The data for na were obtained from the Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIAC).28 Second, to assess the risk of CRS in relation to herd immunity, the absolute number of live births at risk of developing CRS was calculated in relation to time using the age-specific annual number of live births, ba(t), and the age-specific seronegative proportion in the corresponding age-group:

|

where aL and aU represent the lower and upper childbearing ages of mothers, respectively.

All the data that we used were secondary in nature, and all individuals were de-identified in advance of the study.29 For this reason, the present study was exempted from requiring ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board.

Data sharing policy

The summary of secondary data sets that were analysed in the present study can be shared by the corresponding author on request.

Results

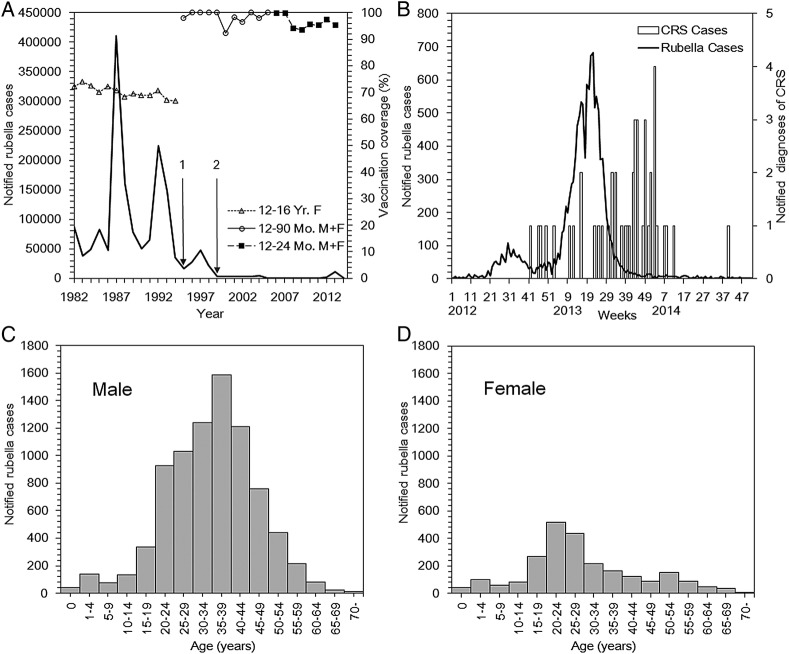

Figure 1A shows the reported rubella cases and the vaccination coverage from 1982 to 2014. Damped oscillation was observed for decades, and the magnitude of the most recent epidemic from 2012 to 2014 appeared to be smaller than those in the 1980s and 1990s. The absolute number of confirmed cases during the major epidemics was: 410 786 in 1987; 223 758 in 1992; 47 599 in 1997; 4248 in 2004; and 10 675 in 2013. Whereas the vaccination coverage in the 1980s was around 70%, the coverage under the routine immunisation programme that began in 1995 to raise herd immunity has been maintained well above 90%. During the most recent epidemic from 2012 to 2014 (figure 1B), there were 12 614 confirmed rubella cases and 45 reported CRS cases. The peak in CRS cases took place in the second week of 2014 with n=4 reported CRS events, which was 33 weeks after the peak of the reported rubella cases in the 21st week of 2013. The time-lag of 33 weeks is consistent with our conventional understanding that the exposure leading to CRS occurs during the first trimester of pregnancy. The average age at infection in 2013 was 34.4 years for males and 24 years for females (figure 1C, D). In the 2012–2014 epidemic, 77% of the cases were male.

Figure 1.

Rubella and CRS in Japan, 1982–2014. (A) The solid line represents the rubella cases reported to the national surveillance from 1982 to 2014. In 1994 (on point 1), a law revision was made to shift the focus from the individual protection of adolescent females to a mass vaccination among infants. In 1999 (on point 2), the Communicable Disease Law with sentinel surveillance was replaced by the Infectious Diseases Control Law. In 2008, the Infectious Disease Law was revised, requiring the reporting of all diagnosed rubella cases. The non-continuous line with data points above the solid line represents the rubella vaccination coverage (first dose) from 1977 to 2013. The shapes of the data points correspond to the change in the vaccination programme, from targeting females aged 12–16 years, to doing so to children aged 12–90 months (typically children aged 12–36 months), to those aged 12–24 months. Some vaccination coverage in the government statistics exceeded 100% because the coverage was calculated as the ratio of the annual number of vaccinations to the population size of an age-group that newly entered the participant age-group of vaccination. (B) Epidemic curve of rubella cases from 2012 to 2014 (left vertical axis). The bold solid line indicates the number of reported rubella cases by week. The bars indicate the number of reported diagnoses of CRS from January 2012 to October 2014, measured on the right vertical axis. (C–D) Age distribution of reported rubella cases in Japan in 2013 among males and females. CRS, congenital rubella syndrome; F, female; M, male; Mo, month; Yr, year.

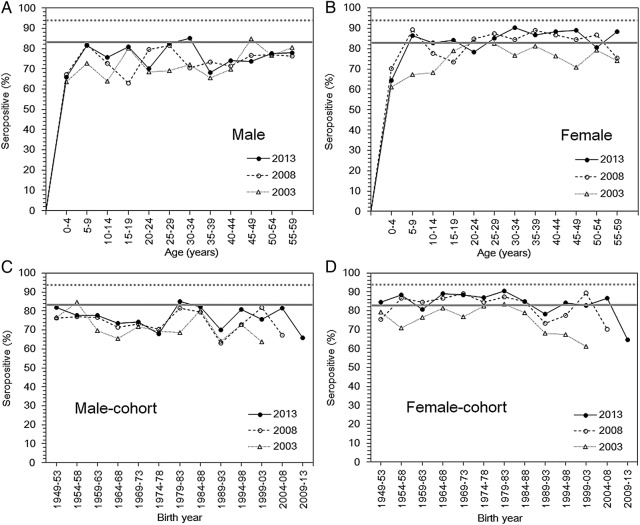

Overall, the seropositive proportion among adults increased over time from 2003 to 2013, except for those aged 20–24 and 45–49 years among males, and 20–29, 35–39 and 50–54 years among females (figure 2). In 2013, the seropositive proportion among males was mostly below the prespecified herd immunity threshold, with the lowest values of 68% and 70% among those aged 35–39 and 20–24 years, respectively (figure 2A). Among females (figure 2B), the seroprevalence in the majority of the age groups was greater than the herd immunity threshold in 2013, but in those aged 20–24 years, the seropositive proportion was only 78.3%. Notable susceptible pockets were identified by graphing the seroprevalence by birth years, which found cohorts born from 1974 to 1978 and 1989 to 1993 at low seroprevalence levels (figure 2C). A minor susceptible pocket in those born from 1989 to 1993 was observed in the female population (figure 2D). If we adopt 94% as the herd immunity threshold, all age groups of both sexes are considered to be susceptible to a rubella epidemic. Although the qualitative age-dependent patterns were not drastically different from those shown in figure 2 when we adopted HI≥8 as the cut-off value (see online supplementary figure S1A–D), having 94% to be considered as the herd immunity threshold, the susceptible pocket among adult males widens, leading those aged 30–34 years to be vulnerable in 2013. Additionally, when we adopted the cut-off value of HI≥8 along with a 94% herd immunity threshold for the birth year cohort, only the adult male population of those born later than 1979–1983, or all males aged 30 years or older in 2013, appeared to be vulnerable (see online supplementary figure S1A,C). If we adopted 83.6% as the threshold with cut-off value of HI≥8, the male adult population, except for those aged 35–39 and 45–49 years, was considered as substantially immune in 2013, while seroprevalence among adult females predominantly appeared to be above the threshold. Even when we accounted for the sensitivity and specificity of serological testing, the findings were similar to those directly obtained from the observed seroprevalence data (see online supplementary figure S2A–D).

Figure 2.

Age-specific rubella-seropositive proportions from 2003 to 2013. The age-specific proportion of males (A) and females (B) that was seropositive for rubella antibodies in Japan based on the seroepidemiological data from 2003, 2008, and 2013. The seropositive proportion is shown as a function of age. A haemagglutination inhibition titre ≥32 was used as the cut-off for deciding if seroconversion had occurred. The horizontal grey bold line, indicating a herd immunity threshold of 83.6%, was the result of the following calculation: 1−(1/basic reproduction number). Therefore, a major epidemic should be prevented above this line. The horizontal grey dotted line indicates an alternative herd immunity threshold of 94%.26 27 Birth cohorts of the rubella-seropositive proportions among males (C) and females (D) in Japan, as a function of birth year, from 1949 to 2013.

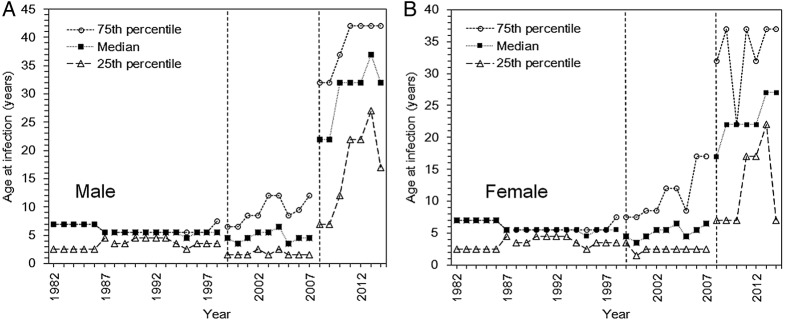

The time series of ages for cases from 1982 to 2014 is shown by gender in figure 3. In 1982, the median (and IQR) age of reported cases was 7 (2.5–7.0) years, among both, males (figure 3A) and females (figure 3B). The median (25–75th centiles) age in 2014 was elevated to 32.0 (17.0–42.0) years among males and 27.0 (7.0–37.0) years among females. From 1982 to 2014, there was a significant time-dependent increase in the age at infection among males and females (p≤0.001), although mandatory reporting of all rubella cases only started in 2008 and cases thereafter might be of older age than before reporting was required by law. Nevertheless, even restricting ourselves to the time from 2008 to 2014, the trend test also indicates a significant time-dependent increase in the age at rubella infection among males (p≤0.01). However, the increase in age at infection among females failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.06).

Figure 3.

Age at infection with rubella in Japan, 1982–2014. (Age at rubella infection in Japan among males (A) and females (B). The dotted line with circles represents the 75th centile of the age distribution of cases, the small dotted line with filled squares indicates the median, and the large dotted line with triangles represents the 25th centile. The data are not continuous because the discrete age category of cases in the reporting system was not consistent throughout the time period. For this reason, the lines are divided when there was a change. Moreover, percentile points are overlapped, especially in the early years of observation. The vertical dotted line in 1999 corresponds to when the infectious disease law was introduced. After the vertical dotted line in 2008, surveillance was drastically revised to enforce the reporting of all cases, including the reporting of cases in adults aged 20 years and older.

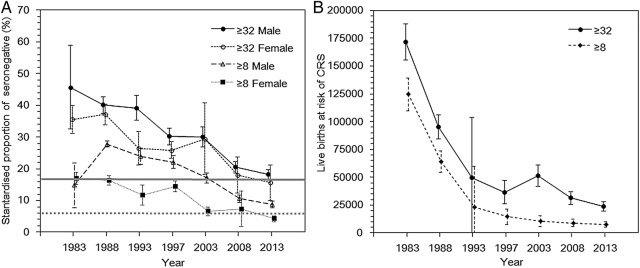

To allow an explicit comparison between the herd immunity threshold and the observed representative value of the seropositive fraction, the age-standardised seronegative proportion, m1, was calculated as a function of time from 1983 to 2013 (figure 4A). The results show that the estimate of m1 steadily dropped in males and females from 1983 to 2013 (figure 4A). While the seronegative proportions in 1983 were 45.7% (95% CI 32.5% to 58.9%) and 35.6% (95% CI 31.2% to 40.0%) among males and females, respectively, the proportions decreased in 2013 to 18.3% (95% CI 16.8% to 19.8%) and 15.6% (95% CI 10.0% to 21.2%), respectively. When the seropositive proportion was compared against the theoretical herd immunity seropositive threshold calculated using R0=6.1 (83.6%), the estimate among males was still below the herd immunity threshold, and that among females was only slightly above the threshold value. Figure 4B shows the number of live births at risk for CRS from 1983 to 2013. The number of susceptible live births in 1983 was calculated as 171 875, which was reduced to 23 697 in 2013. The slope of the decline in figure 4B was sharper than that among females in figure 4A because the decrease in figure 4B reflects the immunised fraction as well as the trend in the decline of the absolute number of births per year.

Figure 4.

Time dependence in the standardised rubella-seronegative proportion and the number of live births at risk for congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) in Japan, 1983–2013. (A) The standardised proportion of the population that was seronegative was analysed by sex every 5 years from 1983. The solid line with filled circles shows the male seronegative proportion (≥32), and the dotted line with unfilled circles represents the female seronegative proportion (≥32). Values were adjusted using the age-specific and gender-specific population sizes.25 The error bars show the 95% CIs derived from a normal approximation to binomial. Samples with haemagglutination inhibition titres ≥8 or ≥32 were considered to be seroconverted. The horizontal bold and dotted grey lines indicate the herd immunity thresholds of 83.6% and 94%, respectively,26 27 which were calculated by 1−(1/basic reproduction number). Therefore, a major epidemic should be prevented below this line. (B) The number of live births at risk for developing CRS. The number of live births at risk was calculated from 1983 to 2013; the age-specific annual number of live births was multiplied to the age-specific seronegative proportion in the corresponding age-group and the product was summed over age to yield a standardised proportion. Since the statistics for the number of live births by age of mothers were not available for every corresponding year, the data from the closest year available were taken into account.26 Owing to the nature of the calculation, the estimates reflect both the decreasing proportion of women at childbearing age who were seronegative for rubella as well as the decreasing number of babies delivered over time. The error bar represents the 95% CIs derived from a normal approximation to binomial.

Discussion

The present study assessed the herd immunity against rubella in Japan, characterising the special epidemiological features that led Japan to experience the 2012–2014 rubella epidemic. We identified susceptible pockets, especially among adult male cohorts, which were an important factor that helped the epidemic to take off. There has been an elevation in the average age at infection, making rubella control more difficult. Although the absolute number of rubella cases was smaller in the 2012–2014 rubella epidemic than in earlier epidemics (figure 1A), the occurrence of this epidemic was fuelled by insufficient herd immunity. The unfortunate tragedy that was identified in Greece in the 1990s9 has been repeatedly experienced by present day Japan. While a recently published study focused on estimating the impact on the age-specific rubella seroprevalence of the most recent epidemic in Japan from 2012 to 2014,24 the present study has comprehensively assessed the herd immunity in Japan through the analysis of longitudinal seroepidemiological data, which allowed us to compare between the age-standardised seropositive proportion and the theoretical herd immunity threshold, and, moreover, an elevated age at infection over time was confirmed based on an analysis of reported case data.

Mass vaccination lessens the force of infection and may lead to an elevated age at infection; therefore, it is essential to attain sufficient vaccination coverage to achieve herd immunity, in order to prevent complications, such as infections among pregnant women.30 31 In addition to the elevated age of rubella cases, the present study has shown that Japan has unvaccinated cohorts that were effectively left susceptible until their 30s and 40s, perhaps contributing to an increased opportunity for women of childbearing age to be infected. The epidemic in Japan has indicated that a major rubella epidemic can occur with adult patients making up the majority of cases. Given the limited immunising effect of the 2012–2014 epidemic,24 our findings call for a supplementary vaccination among those remaining susceptible.

Considering these findings, an important conclusion from the present study is that public health policymakers must make sure that susceptible pockets are not left when switching the vaccination policy from an individual-centred prevention programme to one aiming to achieve herd immunity or when introducing a new mass vaccination programme. Seroepidemiological studies can help to monitor susceptible fractions over time and age, so that susceptible pockets will not remain in the population. Identifying susceptible groups and optimising prioritised birth cohorts will be the subject of our future study.

A few limitations of this study should be noted. First, we adopted 1:8 and 1:32 HI titres to define the seropositive cases, but employing these cut-off values might not accurately capture all of the susceptible individuals. To minimise the effect of this limitation, we have implemented sensitivity analyses using two different cut-off values and two different herd immunity threshold levels. Second, we did not explore any geospatial dynamics, although the major rubella epidemics mostly occurred in urban settings.32 The spatiotemporal analysis of rubella epidemics is one of our ongoing research subjects. Third, our analysis of age at infection among reported cases was biased by the selection of sentinel medical facilities and, thus, the estimated ages might be biased, especially those prior to 2008. Nevertheless, the elevation of age at infection among the male population was observed even when we focused on the years from 2008 onward.

In conclusion, the present study comprehensively demonstrated an elevated age at infection with rubella and the presence of susceptible pockets, especially among adult males, as two important factors that have characterised the rubella epidemic in Japan from 2012 to 2014. Even though the large epidemic might be over, it is important to remember that this population remains vulnerable to rubella infection and could lead to further CRS cases unless supplementary vaccination is conducted.

Footnotes

Contributors: HN conceived the study and directed RK. RK collated and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript and text for figures. HN edited the earlier versions of the manuscript. Both the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; Daiwa Securities Health Foundation; Public Health Research Foundation; Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology, Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: HN received funding support from the Public Health Research Foundation, Daiwa Securities Health Foundation, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant numbers 26670308 and 26700028), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST programme, and the RISTEX programme for Science, of the Science, Technology and Innovation Policy.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lambert N, Strebel P, Orenstein W et al. Rubella. Lancet 2015;385:2297–307. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60539-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best JM. Rubella. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2007;12:182 10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duszak RS. Congenital rubella syndrome—major review. Optometry 2009;80:36 10.1016/j.optm.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugishita Y, Takahashi T, Hori N et al. Ongoing rubella outbreak among adults in Tokyo, Japan, June 2012 to April 2013. Western Pac Surveill Response J 2013;4:37–41. 10.5365/WPSAR.2013.4.2.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) Japan; Tuberculosis and Infectious Diseases Control Division (TIDCD), Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (MHLW). Infectious Agents Surveillance Report, 1982–2014, National Epidemiological Surveillance for Infectious Diseases (NESID).

- 6.National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID). Case report of CRS. Infectious Agents Surveillance Report 2014. http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/ja/rubella-m-111/rubella-top/700-idsc/5072-rubella-crs-20141008.html (in Japanese).

- 7.Yamada T, Mochizuki J, Hanaoka M et al. Effects of campaign for postpartum vaccination on seronegative rate against rubella among Japanese women. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:152 10.1186/1471-2334-14-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minakami H, Kubo T, Unno N. Causes of a nationwide rubella outbreak in Japan, 2012–2013. J Infect 2014;68:99–101. 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panagiotopoulos T, Antoniadou I, Valassi-Adam E. Increase in congenital rubella occurrence after immunisation in Greece: retrospective survey and systematic review. BMJ 1999;319:1462–7. 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous. Nationwide rubella epidemic—Japan, 2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:452–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ujiie M, Nabae K, Shobayashi T. Rubella outbreak in Japan. Lancet 2014;383:1460–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60712-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua YX, Ang LW, Low C et al. An epidemiological assessment towards elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome in Singapore. Vaccine 2015;33:3150–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ang LW, Chua LT, James L et al. Epidemiological surveillance and control of rubella in Singapore, 1991–2007. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2010;39:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khandaker G, Zurynski Y, Jones C. Surveillance for congenital rubella in Australia since 1993: cases reported between 2004 and 2013. Vaccine 2014;32:6746–51. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castillo-Solórzano C, Reef SE, Morice A et al. Rubella vaccination of unknowingly pregnant women during mass campaigns for rubella and congenital rubella syndrome elimination, the Americas 2001–2008. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl 2):S713–17. 10.1093/infdis/jir489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castillo-Solórzano C, Marsigli C, Bravo-Alcántara P et al. Elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome in the Americas. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl 2):S571–8. 10.1093/infdis/jir472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smits G, Mollema L, Hahné S et al. Seroprevalence of rubella antibodies in The Netherlands after 32 years of high vaccination coverage. Vaccine 2014;32:1890–5. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vynnycky E, Gay NJ, Cutts FT. The predicted impact of private sector MMR vaccination on the burden of congenital rubella syndrome. Vaccine 2003;21:2708–19. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkusa Y, Sugawara T, Arai S et al. Short-term prediction of the incidence of congenital rubella syndrome. Plos Curr 2014;6 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.8c74272f4348781c5d01c81e6150c2f7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cutts FT, Vynnycky E. Modelling the incidence of congenital rubella syndrome in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:1176–84. 10.1093/ije/28.6.1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW). Committee of NESVPD in National Institute of Infectious Diseases. 2003, 2008, 2013. Procedure for the National Epidemiological Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (in Japanese).

- 22.Nabae K, Satoh H, Nishiura H et al. Estimating the risk of parvovirus B19 infection in blood donors and pregnant women in Japan. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e92519 10.1371/journal.pone.0092519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW). Vaccination coverage of routine vaccination. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/bcg/other/5.html

- 24.Nishiura H, Kinoshita R, Miyamatsu Y et al. Investigating the immunizing effect of rubella epidemic in Japan, 2012–14. Int J Infect Dis 2015;38:16–18. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanaan MN, Farrington CP. Matrix models for childhood infections: a Bayesian approach with applications to rubella and mumps. Epidemiol Infect 2005;133:1009–21. 10.1017/S0950268805004528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plans-Rubió P. Evaluation of the establishment of herd immunity in the population by means of serological surveys and vaccination coverage. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012;8:184–8. 10.4161/hv.18444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plans P. New preventive strategy to eliminate measles, mumps and rubella from Europe based on the serological assessment of herd immunity levels in the population. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013;32:961–6. 10.1007/s10096-013-1836-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIAC). Statistics Japan. http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2013np/ (in Japanese).

- 29.Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW). Demographic statistics of age of mothers giving birth. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai10/toukei03.html (in Japanese).

- 30.Nokes DJ, Anderson RM, Anderson MJ. Rubella epidemiology in South East England. J Hyg (Lond) 1986;96:291–304. 10.1017/S0022172400066067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massad E, Burattini MN, de Azevedo Neto RS et al. A model based design of a vaccination strategy against rubella in a non-immunized community of São Paulo State, Brazil. Epidemiol Infect 1994;112:579–94. 10.1017/S0950268800051281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugishita Y, Shimatani N, Katow S et al. Epidemiological characteristics of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome in the 2012–2013 epidemics in Tokyo, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 2015;68:159–65. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]