Abstract

Objectives

The increased incidence of multiple myeloma (MM) across China and East Asia stimulated us to examine the current rates in Great Britain, where rates increased dramatically in the second half of the 20th century. However, rates have been stable and high during this period in Malmö, Sweden, where there is a keen interest in MM. We thus assessed recent changes in MM incidence in Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö, Sweden, and examined how these changes might explain recent reports of increased MM incidence across Asia.

Design

Estimation of MM incidence for Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö, Sweden.

Populations

MM incidence data for Great Britain (1975–2009) were obtained from Cancer Research UK and for Sweden (1970–2009) from the Swedish Cancer Registry. MM incidence data from Malmö, Sweden, were available from 1950 to 2012.

Main outcome measures

Age-specific incidence of MM in Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö, Sweden.

Results

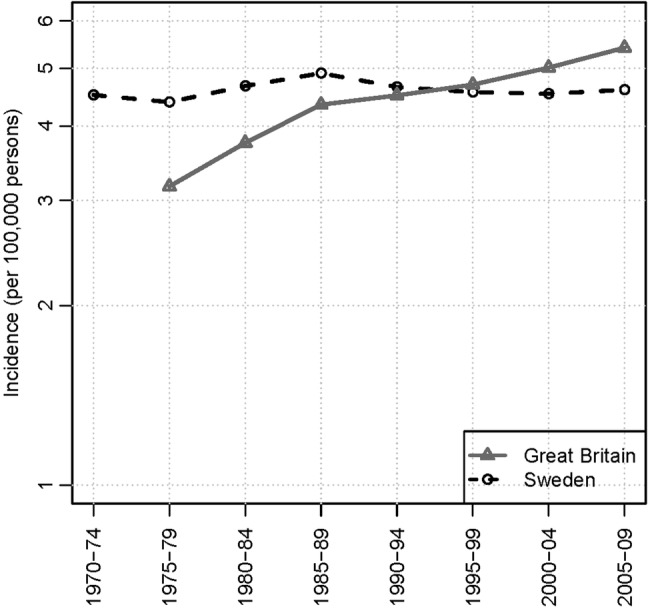

MM incidence in Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö increased progressively with age, even among the oldest group. The MM age-adjusted incidence (European standard population) increased by 69% from 1975–1979 to 2005–2009 in Great Britain, from 3.2/100 000 to 5.4/100 000. The largest increases occurred among those 70–79 years of age, for whom rates increased from 17.9/100 000 to 33.6/100 000; reflecting an increase of 69%. During this same period, the age-adjusted incidence (European stand population) in Sweden overall remained stable, at approximately 4.7/100 000.

Conclusions

MM age-specific incidence is now similar in Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö. We believe this is a result of improvements in case ascertainment in Great Britain, particularly among the elderly. Similar changes can be predicted to occur across Asia as improved access to healthcare contributes to better diagnosis of MM.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is an a priori hypothesis-driven study. Prior reports of stable age-adjusted and age-specific multiple myeloma (MM) incidence rates in Malmö, Sweden, had suggested that increasing incidence rates occurring elsewhere in the world might be attributable to improvements in case ascertainment.

We used a population-based study design. MM incidence rates over time were compared for Great Britain, Sweden, as a whole and Malmö. All have well-established cancer incidence registries.

We analysed time trends across populations. This allowed for comparisons of changes in MM incidence in Great Britain and Sweden as compared with Malmö, where MM incidence rates have been stable since the 1950s.

The study covers a long period of time (1975–2009) and minor changes in diagnostic criteria for MM cannot be excluded, such as cases of smoldering myeloma or solitary plasmacytomas being counted as MM.

Birth cohort analyses have not yet been performed for Great Britain and Sweden. This may give further support that the changes in incidence in Great Britain can be attributed to mainly to an age-period-cohort effect, due mainly to diagnostic improvements in case detection in persons age 65 and older.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell neoplasm first described in England in 1845.1 Its incidence increased dramatically in Great Britain, the USA and in Western Europe in the second half of the 20th century, and the proportional increase was exceeded only by that of lung cancer.2 3 This trend aroused suspicion that occupational and environmental factors might have contributed to these changes.3–5 We previously reported increasing trends in MM mortality in England and Wales from 1950 to 1979 and provided evidence to support that this increase was largely due to increasing case ascertainment, particularly among the elderly.6 Subsequently, we demonstrated a stable age-adjusted incidence in Malmö, Sweden, where there has been a long-term interest in MM, and we suggested that the rates in Malmö were likely the asymptotes towards which MM incidence will increase in other populations.7 8 Recent reports of the increased incidence of MM cases in China and other Asian countries9–11 prompted us to re-examine the incidence of MM in Great Britain and compare it with the incidence in Sweden to evaluate whether the trends reported previously had continued. Assuming that the temporal changes in MM mortality previously observed in Great Britain were largely due to an ascertainment bias, we hypothesised that the age-specific incidence of MM in Great Britain should now approximate the rates observed in Malmö, Sweden, where rates have been stable since the 1950s and where age-specific rates increase sharply for both sexes, even into the oldest age group.8 We believe that the changes now occurring throughout Asia are also driven by increasing case ascertainment and not necessarily by environmental or occupational exposures.

Methods and populations

MM incidence data for the UK overall and for Great Britain were obtained from the Cancer Research UK website.12 Cancer statistics for the UK are aggregated from cancer registries in England (eight regional registries), Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Data from Northern Ireland were only available beginning in 1995, so for consistency our paper focuses on Great Britain (ie, England, Wales and Scotland). Cancer records are subjected to extensive quality control measures before they are released.13 For our analyses of MM incidence and trends, we used data on incidence of MM for Great Britain, defined by 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code, by 5-year age group and sex for the period 1975–2009. These data were provided by Cancer Research UK, who in turn received the data from UK Association of Cancer Registries.14 Data beyond 2009 were not used due to issues with late registration.

Incidence data for Sweden were obtained from the Swedish Cancer Registry. National incidence data for MM and other malignancies became available in Sweden beginning in 1958, when all physicians were required by law to report new cases of cancer to the centralised nationwide Swedish Cancer Registry. In a recent validation study focusing on lymphoproliferative malignancies diagnosed from 1964 through 2003, we found the completeness and overall accuracy of the registry to be greater than 90–95%.15

The methods of data collection and a description of the population in Malmö, Sweden, have been described in our previous reports.7 8 Patients with solitary plasmacytomas were only included if they developed generalised MM. This criterion is a limitation in our statistics for the Malmö myeloma population, but since solitary plasmacytomas represent less than 5% of all plasma cell neoplasms, it has only a minor impact on the interpretation of the results.16

Incidence figures for Malmö are reported separately from those of Sweden overall to enable comparison of incidence trends in this population with those from 1950 (ie, before the start of the National Swedish Cancer Registry). We believe that the close surveillance of this population, including that patient records of all incident M-proteins detected by the central laboratory of the Department of Clinical Chemistry between 1950 and 2009 were investigated, suggests that the rates in Malmö represent the asymptotes towards which rates for other Caucasian populations will increase as case ascertainment improves.

Poisson likelihood-ratio 95% CIs for incidence rates were used.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Lund (protocol number 2015/20).

Results

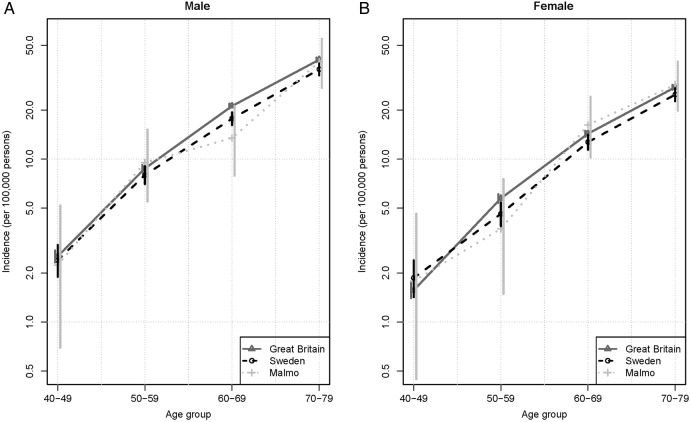

MM age-specific incidence rates for Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö are shown in figure 1. The three curves are very similar and show increasing incidence with age in all three cohorts. There was no decrease in incidence with ageing, as had been previously demonstrated for England and Wales.6 CIs for Great Britain are very small, Sweden slightly larger, and Malmö largest and cover Sweden and Great Britain. MM age-adjusted rates (European standard population) for Great Britain increased from 3.167/100 000 (95% CI 3.166 to 3.168) in 1975–1979 to 5.410 (95% CI 5.409 to 5.411) in 2005–2009. Most of this increase occurred in older individuals, where rates increased from 17.85/100 000 (95% CI 17.56 to 18.47) for those 70–79 years of age in 1975–1979 to 33.56/100 000 (95% CI 32.78 to 34.34) in 2005–2009. In 2005–2009, some 59% of MM cases in Great Britain were diagnosed in people age 70 years or older.14

Figure 1.

Age-specific multiple myeloma incidence rates for Great Britain (2005–2009), Sweden (2005–2009), and Malmö, Sweden (2000–2009).

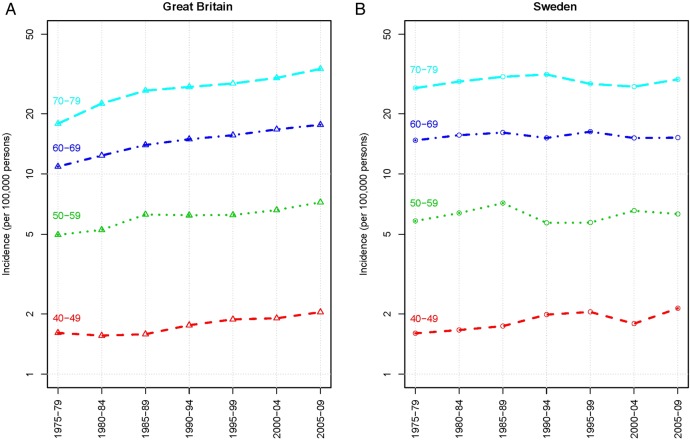

We compared age-standardised (European standard population) incidences of MM for Great Britain and Sweden (figure 2). Overall rates did not increase for Sweden between 1975 and 2009. A substantial increase was observed over the same period for Great Britain, where increases in the age-specific rates occurred primarily among the elderly but no increases occurred in Sweden for these age groups: for those 70–79 years incidence was 29.7 (95% CI 27.9 to 31.6)/100 000 in 1975–1979 and 26.9 (95% CI 25.1 to 28.7)/100 000 in 2005–2009 (figure 3).

Figure 2.

European age-standardised incidence rates for multiple myeloma (persons) for Great Britain and Sweden.

Figure 3.

Age-specific multiple myeloma incidence rates per 100 000 person-years for Great Britain and Sweden.

The national age-adjusted incidence of MM in Sweden overall increased during the first decade of reporting, approaching the incidence in Malmö, and from 1970 onward remained stable at levels similar to those in Malmö. This curve may reflect a slow initial start in complete case reporting to the National Registry. We examined the 5-year average age-specific incidences for both men and women from 1970–1974 through 2005–2009 (data not shown) and found them to be essentially unchanged and similar to those for Sweden from 2010 to 2012 (figure 1).

Discussion

Over the past 60 years, our ability to diagnose MM has improved greatly with the advent of special diagnostic tests, such as complete metabolic panels, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, and quantitative immunoglobulins.17 Variable access to testing and changes in clinical practice and disease awareness have led to variable disease incidences in different populations.18 Previously, we reported that the age-adjusted and age-specific incidences of MM in Malmö, Sweden, had remained stable since the 1950s.8 This stability has been attributed to a stable population receiving unrestricted access to healthcare and a keen awareness of MM, which began in 1949 with Dr Jan Waldenstrom at Malmö General Hospital. We now present data for Sweden overall, where, with the exception of the earliest time period, rates were parallel to the rates for Malmö. A major strength of our study is the use of a validated Swedish tumour registry and comparison with the population of Malmö, where all patient records were reviewed to ensure that the same diagnostic criteria were used during the study period. Similar stable incidence rates have been reported from Olmstead County, Minnesota, USA.19 Both Olmstead County and Malmö have high levels of disease surveillance. Given the geographic and exposure differences between these two populations, it is unlikely that these rates are a consequence of environmental and/or occupational exposures; they more likely represent the true incidence of MM in Caucasian populations, supporting our hypothesis of an asymptote towards which MM rates in Caucasian countries will increase with improvements in case ascertainment. We also found this increase in age-specific rates of MM has occurred in Great Britain, where rates are now similar to rates in Sweden overall and in Malmö. There is no longer a decrease in age-specific rates at older ages, but the age-specific incidence rates for Great Britain and Sweden are now similar to those for Malmö, Sweden, where there is a sharp and continual increase with age.

Extrapolating from the results of our study, we predict that the secular changes that occurred in Great Britain are now occurring in China and across East Asia. The data from Sweden argue strongly against the notion that environmental exposures (other than those related to access to healthcare and increased disease surveillance across all ages, especially among the elderly) were responsible for the changes in incidence. Another important consequence shown in our study is the increase in the number of new and prevalent cases as a result of an ageing population (data not shown). We can expect the number of prevalent cases worldwide to increase as a result of this phenomenon. Although concerns for potential new risk factors need to be addressed, the challenge for clinicians will be how to provide care to these patients. This challenge will provide a greater impetus for developing novel treatment strategies that are easier to administer to and better tolerated by the increasing number of elderly patients with myeloma.20 21

Conclusion

MM age-specific incidence rates are similar in Great Britain, Sweden overall, and Malmö, Sweden. Our analysis suggests that these rates are now similar as a result of improvements in case ascertainment in Great Britain, particularly among the elderly. The rates in Malmö and in Sweden overall have remained remarkably stable and at a higher rate than those worldwide because of Sweden's organisation of healthcare and interest in this disease. Changes similar to those observed for Great Britain can be predicted to occur across Asia as improved access to healthcare contributes to a better diagnosis of MM.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms Emily Blankenship and Ms Amanda Goode for their assistance with manuscript preparation. They are also grateful to Adam Brentnall for statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: RV, IT and JC contributed to the conception of this study as well as data acquisition. OL, SYK and all other co-authors contributed to data analysis and writing and revisions of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Clamp JR. Some aspects of the first recorded case of multiple myeloma. Lancet 1967;2:1354–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(67)90935-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devesa SS, Silverman DT. Cancer incidence and mortality trends in the United States: 1935–74. J Natl Cancer Inst 1978;60:545–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraumeni JF. Environmental and genetic determinants of cancer. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 1977;1:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander DD, Mink PJ, Adami H-O et al. . Multiple myeloma: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Int J Cancer 2007;120(Suppl 12):40–61. 10.1002/ijc.22718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang S-Y, Yao M, Tang J-L et al. . Epidemiology of multiple myeloma in Taiwan: increasing incidence for the past 25 years and higher prevalence of extramedullary myeloma in patients younger than 55 years. Cancer 2007;110:896–905. 10.1002/cncr.22850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velez R, Beral V, Cuzick J. Increasing trends of multiple myeloma mortality in England and Wales; 1950–79: are the changes real? J Natl Cancer Inst 1982;69:387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turesson I, Zettervall O, Cuzick J et al. . Comparison of trends in the incidence of multiple myeloma in Malmö, Sweden, and other countries, 1950–1979. N Engl J Med 1984;310:421–4. 10.1056/NEJM198402163100703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turesson I, Velez R, Kristinsson SY et al. . Patterns of multiple myeloma during the past 5 decades: stable incidence rates for all age groups in the population but rapidly changing age distribution in the clinic. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:225–30. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brian GM, Durie MD. International Myeloma Foundation. http://myeloma.org (accessed 9 Apr 2015).

- 10.Riedel DA, Pottern LM. The epidemiology of multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1992;6:225–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K, Lee JH, Kim JS et al. . Clinical profiles of multiple myeloma in Asia-An Asian Myeloma Network study. Am J Hematol 2014;89:751–6. 10.1002/ajh.23731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UK CR. Myeloma incidence statistics. 2014. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/myeloma/incidence/uk-multiple-myeloma-incidence-statistics (accessed 9 Apr 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray F, Parkin DM. Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods. Part I: comparability, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990 2009;45:747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mistry M, Parkin DM, Ahmad AS et al. . Cancer incidence in the United Kingdom: projections to the year 2030. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1795–803. 10.1038/bjc.2011.430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turesson I, Linet MS, Björkholm M et al. . Ascertainment and diagnostic accuracy for hematopoietic lymphoproliferative malignancies in Sweden 1964–2003. Int J Cancer 2007;121:2260–6. 10.1002/ijc.22912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Mendenhall NP. Solitary plasmacytoma of bone and soft tissues. Am J Otolaryngol 2003;24:395–9. 10.1016/S0196-0709(03)00092-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu DC, Wilkenfeld P, Joshua DE. Multiple myeloma. BMJ 2012;344:d7953 10.1136/bmj.d7953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuzick J, Velez R, Doll R. International variations and temporal trends in mortality from multiple myeloma. Int J Cancer 1983;32:13–19. 10.1002/ijc.2910320104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV et al. . Incidence of multiple myeloma in Olmsted County, Minnesota: trend over 6 decades. Cancer 2004;101:2667–74. 10.1002/cncr.20652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan D, Chng WJ, Chou T et al. . Management of multiple myeloma in Asia: resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e571–81. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70404-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson BO. Evidence-based methods to address disparities in global cancer control: the development of guidelines in Asia. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1154–5. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70496-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]