Abstract

Objective

The primary aim was to study pregnancy hypertensive disease and subsequent risk of dementia. The second aim was to study if the increased risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke after pregnancy hypertensive disease persist in an elderly population.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Population or sample

3232 women 65 years or older (mean 71 years) at inclusion.

Methods

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to calculate risks of dementia, CVD and/or stroke for women exposed to pregnancy hypertensive disease. Exposure data were collected from an interview at inclusion during the years 1998–2002. Outcome data were collected from the National Patient Register and Cause of Death Register from the year of inclusion until the end of 2010. Age at inclusion was set as a time-dependent variable, and adjustments were made for body mass index, education and smoking.

Main outcome measures

Dementia, CVD, stroke.

Results

During the years of follow-up, 7.6% of the women exposed to pregnancy hypertensive disease received a diagnosis of dementia, compared with 7.4% among unexposed women (HR 1.19; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.73). The corresponding rates for CVD were 22.9% for exposed women and 19.0% for unexposed women (HR 1.29; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.61), and for stroke 13.4% for exposed women and 10.7% for unexposed women (HR 1.36; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.81).

Conclusions

There was no increased risk of dementia after self-reported pregnancy hypertensive disease in our cohort. We found that the previously reported increased risk of CVD and stroke after pregnancy hypertensive disease persists in an older population.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study addressing a potential association between hypertensive complications during pregnancy and dementia later in life.

The strengths of this study lie in the well-characterised cohort and our ability to follow-up women during a life period with a suspected high prevalence of dementia.

The major limitation of our study was that the information on pregnancy hypertensive disease was self-reported and collected many years after pregnancy.

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia used to be regarded as an isolated event during pregnancy and delivery, but we now know that women with a pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as ischaemic heart disease and stroke, later in life.1 2 Pre-eclampsia and CVD share many risk factors, including obesity and diabetes.3 Pregnancy has been described as a stress test for the cardiovascular system, where the demands of pregnancy unmask underlying phenotypic susceptibility to CVD.4 There is also the possibility that pre-eclampsia is an independent risk factor due to endothelial changes during the pregnancy, changes that have been shown to persist at least years after the pregnancy.5 Most previous studies of the association between pre-eclampsia and later CVD are limited to follow-up of women who have not yet reached menopause,1 and studies focusing on pre-eclampsia and CVD risk in elderly women (>65 years) are lacking. Since the risk of CVD generally increases with age,6 7 the effect of pre-eclampsia may vary with age of follow-up.

The prevalence of dementia is increasing worldwide. It has been estimated that the number of people living with dementia will almost double in the coming 20 years.8 The prevalence increases with age and is very rare in women below 65 years.9 Dementia is a heterogeneous disorder with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia being the two most common types.

When followed up several years after the index pregnancy, women with eclampsia and pre-eclampsia have significantly more brain white matter lesions on MRI than controls with normotensive pregnancies.10 11 These lesions can have different causes and be asymptomatic, but are often due to microangiopathy and have been found to correlate with impaired cognition and dementia, especially in periventricular location.12 13 There are also recent reports of detectable cognitive impairment a few months after severe pre-eclampsia, and self-reported impairment of cognitive function up to 7 years after eclampsia.14 15 On the basis of these findings together with the known association between pre-eclampsia and different cardiovascular complications, we hypothesised that pregnancy hypertensive disease is associated with increased dementia risk.

In this study, we included women 65 years or older. The primary aim was to explore if women with a history of pregnancy hypertensive disease have an increased risk of dementia. Second, we wanted to study if pregnancy hypertensive disease is associated with increased risks of CVD and stroke in this elderly population.

Material and method

Study population

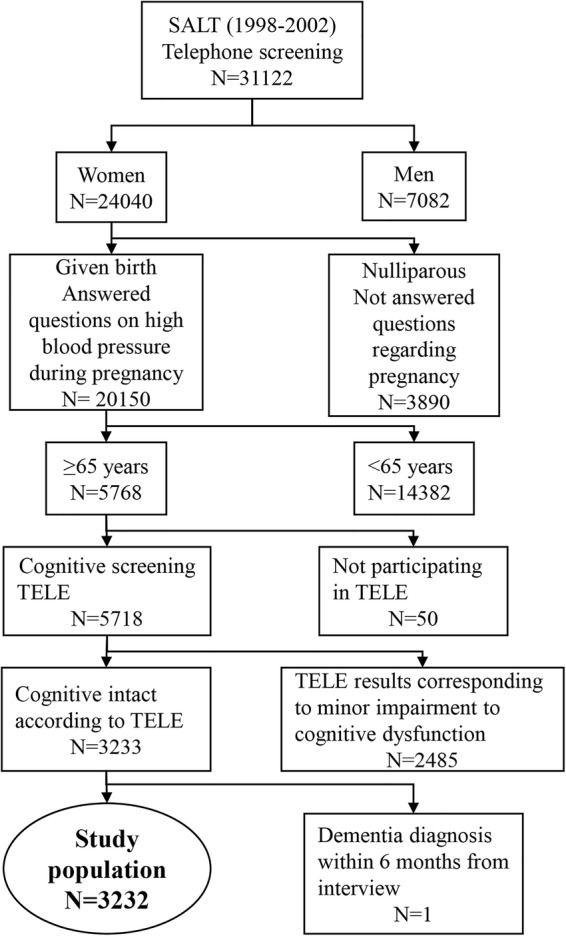

The cohort was retrieved from the nationwide Swedish Twin Register.16 Between 1998 and 2002, all twins in the Register born in 1958 or earlier were invited to a telephone interview, which was a part of the SALT (Screening Across the Lifespan Twin) study.16 17 The interview included questions about pregnancy complications, such as whether or not they had suffered from high blood pressure during pregnancy and, if so, also from proteinuria. Further, it included general questions, such as current weight and height, years of education and smoking habits. For those who were 65 years or older at the time of the interview, the interview included a short cognitive screening test called TELE.18 The cognitive test included the Mental Status Questionnaire, combined with other cognitive items, such as three-word recall, counting backwards and questions about the need for help with daily life due to memory impairment. In our study population, we included women who had given birth, answered questions regarding hypertensive complications during pregnancy, were 65 years or older at the interview and performed the cognitive screening TELE (figure 1). Since exposure data of our study were collected at the time of interview, we excluded women who were not cognitive intact according to the TELE test. We also excluded one woman who had a dementia diagnosis within 6 months after the interview, although she was screened cognitively intact at the interview. The final study population included 3232 women, aged 65 years or more with available self-reported data on pregnancy hypertensive disorder and intact memory at the start of follow-up (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population (SALT, Screening Across the Lifespan Twin).

Exposure data

The exposure was a history of pregnancy hypertensive disease and data were retrieved from the interview, which included two questions regarding hypertension and pregnancy. The first question was if the woman had high blood pressure during any pregnancy (yes/no/do not know). The second question was, if she had high blood pressure, did she also have proteinuria (yes/no/do not know). First, we divided the women into five groups: (1) no hypertension; (2) pre-eclampsia (yes for both hypertension and proteinuria); (3) gestational hypertension (yes for hypertension and no for proteinuria); (4) high blood pressure, unclear proteinuria (yes for hypertension and do not know for proteinuria) and (5) do not know (do not know for hypertension). In further analyses, we combined the second, third and fourth groups to ‘any hypertensive complication’.

Outcome data

The primary outcome was a diagnosis of dementia and the secondary outcomes were diagnosis of CVD and stroke after the time of the interview. Outcome data were retrieved from the National Patient Register and the Cause of Death Register. Linkage between the Swedish Twin Register and the National Patient Register and Cause of Death Register was made possible through each individual's unique personal registration number. The National Patient Register includes information on dates of hospital admissions and diagnoses, which are classified according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. From 1987, the registry includes all in-patient care in Sweden and from 2001 also hospital outpatient visits. ICD diagnoses for each diagnosis are presented in online supplementary table S1.

Covariates

Covariates in the study were collected at the time of the interview and included age (continuous) at interview; current body mass index (BMI) (continuous), education (9 years of school/ >9 years of school) and current smoking habits (daily smoking, yes/no).

Statistics

Risks of dementia, CVD and stroke after pregnancy hypertensive disease were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models and age at interview was set as a time-dependent variable. Women who reported no pregnancy hypertensive disease were the reference. Adjustments were made for BMI, education and smoking at the time of interview. To account for relatedness (twins), the analyses were clustered on twin-pair identity. The regression parameters in the Cox model were estimated by the maximum partial likelihood estimates under an independent working assumption and a robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used to account for the intracluster dependence.19

Results

Table 1 includes the basic characteristics of the study population at the time of interview (ie, start of follow-up). Women who did not remember if they had high blood pressure during pregnancy were somewhat older at the interview than the other exposure groups. After exclusion of women who did not remember if they had high blood pressure during pregnancy, 419 of 3065 (14%) women reported that they had at least one pregnancy with pregnancy hypertensive disease. Women who reported that they had a history of pregnancy hypertensive disease had a slightly higher BMI and education, but were less often smokers compared with those without pregnancy hypertensive disease. Women who reported a history of pregnancy hypertensive disease more often had a diagnosis of CVD, but not of stroke, in the Patient Register before the interview.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at the time of the interview (ie, start of follow-up)

| Pregnancy hypertensive disease |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=419) |

Do not know (N=167) | |||||

| No (N=2646) | Any (N=419) | With proteinuria (N=269) | Without proteinuria (N=113) | Unclear proteinuria (N=37) | ||

| Age at inclusion | 71.8±5.6 | 71.0±5.1 | 71.2±5.0 | 71.0±5.4 | 69.9±5.4 | 73.9±6.1 |

| Age at end of follow-up | 82.2±5.6 | 81.5±5.3 | 81.5±5.2 | 81.7±5.5 | 80.5±5.7 | 84.1±6.0 |

| BMI* | 24.9±3.8 | 26.2±4.2 | 26.0±4.2 | 26.4±5.3 | 25.6±3.7 | 24.8±3.5 |

| Education >9 years | 1197 (45.3) | 201 (48.1) | 137 (50.9) | 46 (40.7) | 18 (50.0) | 71 (42.8) |

| Smoking | 254 (9.6) | 28 (6.7) | 20 (7.4) | 6 (5.3) | 2 (5.4) | 22 (13.2) |

| Previous disease† | ||||||

| CVD | 200 (7.6) | 47 (11.2) | 28 (10.4) | 17 (15.0) | 2 (5.4) | 13 (7.8) |

| Stroke | 63 (2.4) | 11 (2.6) | 8 (3.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (5.4) | 11 (6.6) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or numbers (%).

*BMI. Data are missing in 99 women.

†Prior to interview according to the Patient Registry.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Table 2 presents rates of dementia, CVD and stroke after the time of the interview by exposure to pregnancy hypertensive disease. Rates of dementia seemed similar between women who reported a history of pregnancy hypertensive disease and those who did not (7.6% vs 7.4%). Rates of CVD and stroke seemed slightly higher in women who reported a history pregnancy hypertensive disease than those who did not (22.9% vs 19.0% and 13.4% vs 10.7%, respectively).

Table 2.

Rates of dementia, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke after time of interview by exposure to pregnancy hypertensive disease

| Pregnancy hypertensive disease |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

||||||

| No | Any | With proteinuria | Without proteinuria | Unclear proteinuria | Do not know | |

| Dementia (%) | 197 (7.4) | 32 (7.6) | 20 (7.4) | 11 (9.7) | 1 (2.7) | 20 (12.0) |

| CVD (%) | 504 (19.0) | 96 (22.9) | 58 (21.6) | 29 (25.7) | 9 (24.3) | 47 (28.1) |

| Stroke (%) | 284 (10.7) | 56 (13.4) | 38 (14.1) | 15 (13.3) | 3 (8.1) | 27 (16.2) |

Data are presented as numbers (%).

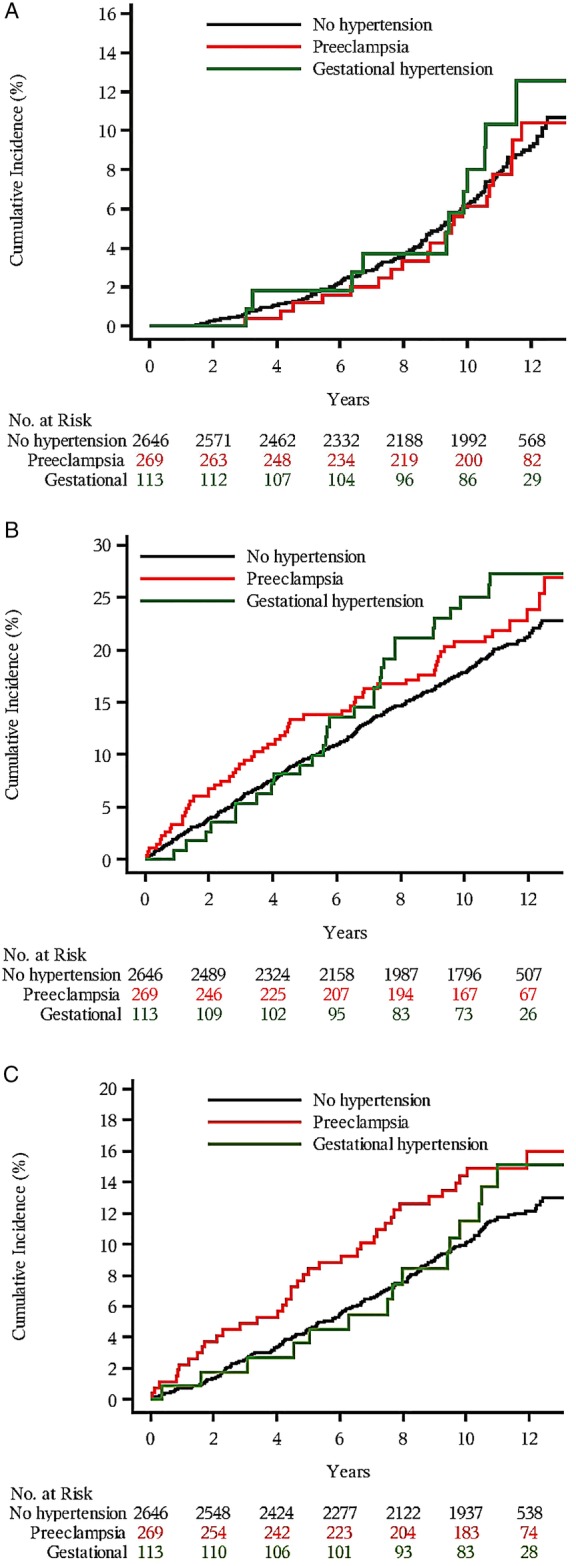

Table 3 presents the risk of dementia after any hypertensive complication during pregnancy, before and after adjustments for confounders. We found no significant association between dementia and pregnancy hypertensive disease. Figure 2A illustrates the cumulative incidence of dementia for women with a history of pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension or no hypertension. The three groups exhibit very similar graphs. If anything, the cumulative incidence of dementia increased with gestational hypertension towards the end of the observation period, possibly reflecting that the overall incidence is quite low at the start of follow-up.

Table 3.

Risk of dementia after time of interview for women with any hypertensive complication in pregnancy compared with women without pregnancy hypertensive disease

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 1.15 | 0.76 to 1.66 | 0.49 |

| Adjusted for education | 1.14 | 0.76 to 1.65 | 0.50 |

| Adjusted for education and smoking | 1.17 | 0.78 to 1.69 | 0.44 |

| Adjusted for education, smoking and BMI | 1.19 | 0.79 to 1.73 | 0.37 |

BMI, body mass index.

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence of dementia (A), cardiovascular disease (CVD) (B) and stroke (C) in women exposed to pre-eclampsia or gestational hypertension, compared with women with a normotensive pregnancy. Timeline from interview until end of 2010.

Table 4 presents risks of CVD and stroke after any hypertensive complication during pregnancy. Women who reported that they had a pregnancy hypertensive disease had slightly higher risks of CVD and stroke compared with women who reported no hypertensive disease.

Table 4.

Risk of CVD and stroke after time of interview for women with any hypertensive complication in pregnancy compared with women without pregnancy hypertensive disease

| HR |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | 95% CI | p Value | Adjusted* | 95% CI | p Value | |

| CVD | 1.29 | 1.02 to 1.61 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 1.02 to 1.61 | 0.03 |

| Stroke | 1.35 | 0.99 to 1.79 | 0.05 | 1.36 | 1.00 to 1.81 | 0.05 |

*Adjusted by BMI, education and smoking.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Figure 2B,C illustrate the cumulative incidences of CVD and stroke by history of pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension or no hypertension. The cumulative incidence of CVD and stroke increased with age in all three exposure groups. For CVD, the increase was slightly higher in women with a history of pre-eclampsia, as well as in women with gestational hypertension compared with non-hypertensive women (figure 2B). Women who experienced pre-eclampsia seemed to be more affected during the first 7 years of follow-up, but thereafter women with pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension were affected. For stroke, pre-eclampsia also conferred an increased risk during follow-up (figure 2C).

Discussion

Main findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing a potential association between hypertensive complications during pregnancy and dementia later in life. We could not detect a significant difference in the incidence of dementia between women with or without a history of pregnancy hypertensive disease. We could also show that the well-established increased risk for CVD in women with previous pre-eclampsia also applies to women of advanced age, but the risk increase seems somewhat lower compared with women in middle age.1

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study lie in the well-characterised cohort and our ability to follow the cohort until an age where the incidences of dementia and CVD are rapidly increasing. The major limitation of our study was that the information on pregnancy hypertensive disease was self-reported and collected many years after pregnancy. We also lacked further information regarding other pregnancy complications, such as giving birth to a preterm or growth retarded infant, that are associated with both our exposure and adverse long-term health of the mother.20 21

Since the need to rely on self-reported data often arises, especially if there is a long period between exposure and outcome, efforts have been made to try to validate these data. Klemmensen et al22 reported a positive predictive value of 59% for self-reported diagnosis of pre-eclampsia in a telephone interview 6–18 months after delivery. In contrast, Falkegård et al23 reported a positive predictive value of 80% for pregnancy hypertensive disease, although their population ranged from 25 to 88 years. To increase the validity of the self-reported data, we only included women who were cognitively intact according to a test performed at the same time as exposure data were collected. The prevalence of dementia in women aged around 80 is supposed to be approximately 12%.24 The incidence of dementia in our cohort was 7.4% and 7.6% in women unexposed and exposed to hypertensive complication in pregnancy, respectively. The major reason for the relatively low incidence in our cohort is probably the requirement of intact cognition at start of follow-up (mean age around 71 years at start). Owing to the study design, our results cannot be generalised to women with early impaired cognition. The association between pregnancy hypertensive disease and risk of CVD is more pronounced in women in middle-ages than among older women.25 This pattern could also be present concerning pregnancy hypertensive disease and risk of dementia. However, owing to the study design, our results cannot be generalised to women with early impaired cognition.

The incidence of any pregnancy hypertensive disease was 14% in our cohort, which is slightly higher than the usual reported incidence of 5–10%.26 Our finding is, however, in line with the results of Klemmensen et al,22 who also reported a higher incidence of self-reported gestational hypertension compared with data from registries.

In a post hoc analysis, using data from the current study regarding the number of women exposed and the observed incidence of dementia, we have estimated that we had the power to detect an 80% difference in risk of dementia between women exposed and unexposed for pregnancy hypertensive disease, with a 80% power and 0.05 significance level.

Our cohort was retrieved from a twin registry with information on pregnancy complications and lifelong follow-up. Compared with singletons, twins have a lower birth weight and shorter gestational length. In singletons, low birth weight and preterm birth are known risk factors for obesity and future CVD.27 28 However, earlier studies have not shown that twins have a higher incidence of CVD than singletons29 30 and both the exposed and non-exposed women in our cohort were twins. Thus, having a study population of twins should not have influenced our results.

Interpretation

We found no increased risk of dementia after self-reported hypertensive pregnancy. Since pregnancy hypertensive disease is associated with later hypertension and CVD, one hypothesis could be that pregnancy hypertensive disease would increase the risk of vascular dementia as opposed to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60–70% of all dementia cases, whereas vascular dementia accounts for approximately 15%.31 The difficulty lies in the reliability of the differential diagnosis. The Swedish Dementia Register reports that 30% of all dementia diagnosis are unspecified.32 Furthermore, the positive predictive value of a vascular dementia diagnosis is 57%.33 To obtain accurate results would therefore require a clinical validation of each patient's dementia diagnosis, which was not possible with our study design. On the other hand, there is support for a vascular aetiology in Alzheimer’s disease,34 35 in which case we would expect an overall increase in dementia diagnoses.

In our study, we could confirm the established link between pre-eclampsia and CVD also in an elderly population.1 36 Our finding concerning CVD is in accordance with the study of Arnadottir et al,25 reporting that pregnancy hypertensive disease was associated with a relative risk of 1.5 of death from CVD in women 65 years or older. We had a somewhat lower point estimate (1.3) compared with Arnadottir, which may be explained by an older study population. Our results extend the results of Arnadottir, since they also apply to morbidity from CVD and are adjusted for smoking and BMI, two important confounders for CVD.37 38 The study by Arnadottir further found that the relative risk for ischaemic heart disease death in women exposed to pregnancy hypertensive disease is higher in women below 65 years than in women 65 years or older (2.4 and 1.5, respectively). It could be that age itself is such an important risk factor that the risk induced by prior hypertensive pregnancy is attenuated. Since the absolute risk of CVD in women increases sharply after menopause, even a small increase in risk at this age has a bigger impact on the total number.

We also found a higher risk of stroke in women with pregnancy hypertensive disease, though with borderline significance. This is in line with previous work of Wilson et al.2 Our finding only refers to risk of stroke in women aged at least 65 years. As stated above concerning CVD, risk of stroke might also be relatively higher in younger than older women after exposure to pregnancy hypertensive disease.

The main hypothesis of the study was that women exposed to pregnancy hypertensive disease would have an increased risk of dementia later in life. Neuroimaging 5 years after eclampsia and pre-eclampsia has shown that women exposed to these pregnancy complications have an increased amount of white matter lesions compared with unexposed women.10 11 Pathological findings corresponding to white matter lesions are myelin loss and mild gliosis.39 Clinically, associations have been shown between white matter lesions and the incidences of stroke, dementia40 and cognitive decline.41 The white matter lesions seen after pre-eclampsia might be interpreted as either permanent brain effects of the disease or, perhaps more plausible, as merely another manifestation of the propensity of women with pre-eclampsia to develop vascular disease.

Conclusion

In this national study, we could not find an association between hypertensive complications during pregnancy and later dementia. Our cohort was retrieved from a twin registry and data on exposure were self-reported at an average age of 70 years. To account for this, we excluded a proportion of women not cognitive of intact at this time point, which can affect the generalisability of our study. Future work in the area is warranted to focus on associations between pregnancy hypertensive disease and subtypes of dementia, including vascular dementia. Demographic trends show an ageing population and increasing prevalence of dementia that will infer a great socioeconomic burden. To identify persons at risk will represent an important preventive strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: A-KW, HÅ and SC had the original idea for the study. MN, SC, HÅ, JW, NLP and A-KW all contributed to the design of the study. MN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MN, SC, HÅ, JW, NLP and A-KW all made substantial contribution to the interpretation of results and manuscript revision.

Funding: Regional Research Council in the Uppsala-Örebro region (project number 224391), the Swedish Research Council (project number 2014-3561), the European Union's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2011) under grant agreement number 259679.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by one of the Regional Ethical Review Boards in Stockholm, Sweden (reference number 2013/496; date of approval 10 April 2013).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD et al. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007;335:974 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson BJ, Watson MS, Prescott GJ et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and risk of hypertension and stroke in later life: results from cohort study. BMJ 2003;326:845 10.1136/bmj.326.7394.845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnussen EB, Vatten LJ, Lund-Nilsen TI et al. Prepregnancy cardiovascular risk factors as predictors of pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ 2007;335:978 10.1136/bmj.39366.416817.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams D. Pregnancy: a stress test for life. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2003;15:465–71. 10.1097/01.gco.0000103846.69273.ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berks D, Steegers EA, Molas M et al. Resolution of hypertension and proteinuria after preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:1307–14. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c14e3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:e28–292. 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The national board of health and welfare. (2013). Report 2013-3-26. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19032/2013-3-26.pdf.

- 8.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E et al. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:63–75.e2. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey RJ, Skelton-Robinson M, Rossor MN. The prevalence and causes of dementia in people under the age of 65 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1206–9. 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aukes AM, de Groot JC, Aarnoudse JG et al. Brain lesions several years after eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:504.e1–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aukes AM, De Groot JC, Wiegman MJ et al. Long-term cerebral imaging after pre-eclampsia. BJOG 2012;119:1117–22. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enzinger C, Fazekas F, Ropele S et al. Progression of cerebral white matter lesions—clinical and radiological considerations. J Neurol Sci 2007;257:5–10. 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, den Heijer T et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and the risk of dementia. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1531–4. 10.1001/archneur.61.10.1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aukes AM, Wessel I, Dubois AM et al. Self-reported cognitive functioning in formerly eclamptic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:365.e1–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brussé I, Duvekot J, Jongerling J et al. Impaired maternal cognitive functioning after pregnancies complicated by severe pre-eclampsia: a pilot case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:408–12. 10.1080/00016340801915127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichtenstein P, De Faire U, Floderus B et al. The Swedish Twin Registry: a unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J Intern Med 2002;252:184–205. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenstein P, Sullivan PF, Cnattingius S et al. The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millennium: an update. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:875–82. 10.1375/183242706779462444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatz M, Reynolds CA, John R et al. Telephone screening to identify potential dementia cases in a population-based sample of older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2002;14:273–89. 10.1017/S1041610202008475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee E, Wei LJ, Amato DA. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations. In: Klein JP, Goel PK, eds. Survival analysis: state of the art. Kulwer Academic Publisher, 1992:237–47. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wikstrom AK, Stephansson O, Cnattingius S. Previous preeclampsia and risks of adverse outcomes in subsequent nonpreeclamptic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:148.e1–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonamy AK, Parikh NI, Cnattingius S et al. Birth characteristics and subsequent risks of maternal cardiovascular disease: effects of gestational age and fetal growth. Circulation 2011;124:2839–46. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.034884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klemmensen AK, Olsen SF, Osterdal ML et al. Validity of preeclampsia-related diagnoses recorded in a national hospital registry and in a postpartum interview of the women. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:117–24. 10.1093/aje/kwm139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falkegård M, Schirmer H, Lochen ML et al. The validity of self-reported information about hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in a population-based survey: the Tromso Study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:28–34. 10.1111/aogs.12514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366:2112–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnadottir GA, Geirsson RT, Arngrimsson R et al. Cardiovascular death in women who had hypertension in pregnancy: a case-control study. BJOG 2005;112:286–92. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner SJ, Barac S, Garovic VD. Hypertensive pregnancy disorders: current concepts. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:560–6. 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06695.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risnes KR, Vatten LJ, Baker JL et al. Birthweight and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:647–61. 10.1093/ije/dyq267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkinson JR, Hyde MJ, Gale C et al. Preterm birth and the metabolic syndrome in adult life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1240–63. 10.1542/peds.2012-2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberg S, Cnattingius S, Sandin S et al. Twinship influence on morbidity and mortality across the lifespan. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1002–9. 10.1093/ije/dys067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrew T, Hart DJ, Snieder H et al. Are twins and singletons comparable? A study of disease-related and lifestyle characteristics in adult women. Twin Res 2001;4:464–77. 10.1375/1369052012803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L et al. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology 2000;54(Suppl 5):S4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Swedish Dementia Registry, SveDem. (2014). Annual report of 2013. http://www.ucr.uu.se/svedem/index.php/alla-dokument/doc_download/204-arsrapport-svedem-2013.

- 33.Jin YP, Gatz M, Johansson B et al. Sensitivity and specificity of dementia coding in two Swedish disease registries. Neurology 2004;63:739–41. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000134604.48018.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelleher RJ, Soiza RL. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in the development of Alzheimer's disease: Is Alzheimer's a vascular disorder? Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3:197–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eriksson UK, Bennet AM, Gatz M et al. Nonstroke cardiovascular disease and risk of Alzheimer disease and dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:213–19. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181d1b99b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wikström AK, Haglund B, Olovsson M et al. The risk of maternal ischaemic heart disease after gestational hypertensive disease. BJOG 2005;112:1486–91. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messner B, Bernhard D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:509–15. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.300156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006;113:898–918. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3666 10.1136/bmj.c3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debette S, Beiser A, DeCarli C et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke 2010;41:600–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuller LH, Shemanski L, Manolio T et al. Relationship between ApoE, MRI findings, and cognitive function in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke 1998;29:388–98. 10.1161/01.STR.29.2.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]