Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease (DED) in workers using visual display terminals (VDT).

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase and Science Direct databases for studies reporting DED prevalence in VDT workers.

Results

16 of the 9049 identified studies were included, with a total of 11 365 VDT workers. Despite a global DED prevalence of 49.5% (95% CI 47.5 to 50.6), ranging from 9.5% to 87.5%, important heterogeneity (I2=98.8%, p<0.0001) was observed. Variable diagnosis criteria used within studies were: questionnaires on symptoms, tear film anomalies and corneoconjunctival epithelial damage. Some studies combined criteria to define DED. Heterogeneous prevalence was associated with stratifications on symptoms (I2=98.7%, p<0.0001), tears (I2=98.5%, p<0.0001) and epithelial damage (I2=96.0%, p<0.0001). Stratification of studies with two criteria adjusted the prevalence to 54.0% (95% CI 52.1 to 55.9), whereas studies using three criteria resulted in a prevalence of 11.6% (95% CI 10.5 to 12.9). According to the literature, prevalence of DED was more frequent in females than in males and increased with age.

Conclusions

Owing to the disparity of the diagnosis criteria studied to define DED, the global prevalence of 49.5% lacked reliability because of the important heterogeneity. We highlight the necessity of implementing common DED diagnostic criteria to allow a more reliable estimation in order to develop the appropriate preventive occupational actions.

Keywords: OPHTHALMOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first meta-analysis on the prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease (DED) in workers using visual display terminals.

The heterogeneity of the DED diagnostic criteria and their measurement as well as the pathological threshold definition applied may explain the large variability in the prevalence reported.

Results from the meta-analysis are therefore unconvincing.

However, we demonstrated a greater homogeneity of prevalence with shared diagnosis criteria and therefore strengthened the need for a common widely standardised definition.

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is one of the most frequently established diagnoses in ophthalmology,1 and represents a growing public health concern, with consequences that remain widely underestimated. This pathology causes significant impact on visual function, which may affect quality of life2–4 and work productivity.5–8 Owing to variability of clinical manifestations and diagnostic criteria, and the poor correlation between clinical signs and symptoms,9 the assessment of its prevalence is difficult to determine, despite an improved understanding of pathogenic factors of acquired DED.

In 2007, the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) conducted a review of the understanding of DED, revisiting the original definition, developing new evidence on the epidemiology of the disease and strategies for diagnosis according to the stage of severity. The revised DED definition was “a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance and tear film instability, with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface”.10 Although the use of displays in workplaces is growing, the prevalence of DED associated with visual display terminal (VDT) workers is uncertain.11 12 We hypothesised that this wide heterogeneity may be explained by inconsistent use of criteria of diagnosis and a diversity of risk factors including different working conditions, age and smoking. A more unified identification of DED in workers may lead to preventive occupational actions.

Thus, we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to more precisely determine the prevalence of DED among VDT workers, taking into account the methodology of diagnosis used. A secondary aim was to identify the most frequently reported risk factors.

Methods

Literature search

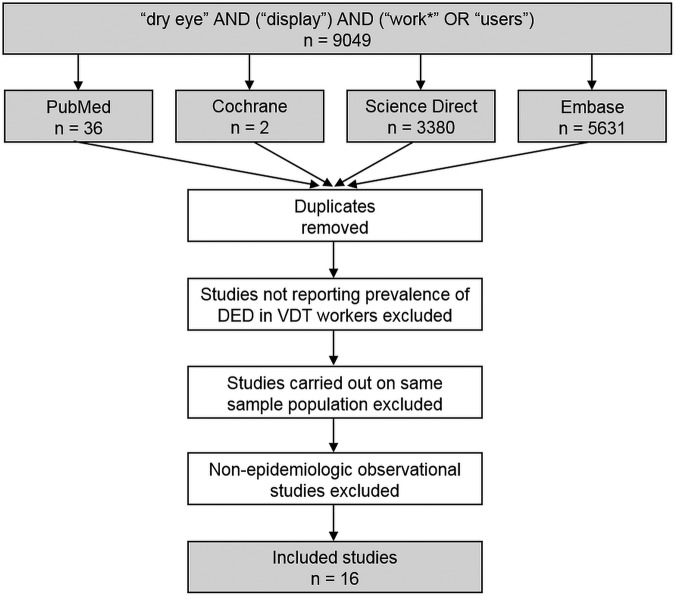

We reviewed all cohort studies involving DED in the VDT user population. Specifically, the inclusion criteria for the search strategy were VDT workers—cohort studies (with a minimum of 10 individuals), without a case-study design—using the following keywords: ‘dry eye’, ‘display’ and ‘users’ or ‘work*’. The following databases were searched on 7 July 2015: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Science Direct and Embase. The search was not limited to specific years and no language restrictions applied. To be included, articles needed to describe our primary outcome variable, which was the number of workers with dry eye disease. In addition, reference lists of all publications meeting the inclusion criteria were manually searched to identify any further studies not found through electronic searching. The search strategy is presented in figure 1. One author (RC) conducted all literature searches and collated the abstracts. Two authors (RC and FD) separately reviewed the abstracts and, based on the selection criteria, decided on the suitability of the articles for inclusion. A third author (CL) was asked to review the article where consensus on suitability was debated. Then, all the authors reviewed the eligible articles.

Figure 1.

Search strategy. DED, dry eye disease; VDT, visual display terminals.

Quality of assessment

Although not designed for quantifying the integrity of studies,13 the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) criteria were used for checking the quality of reporting.14 The 21 items identified in the STROBE criteria could achieve a maximum score of 34.

Statistical considerations

Statistical analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (V.2, Biostat Corporation, Englewood, New Jersey, USA)15 and Stata software (V.13, StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Baseline characteristics were summarised for each study sample, and reported as mean (SD) and number (%), for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Prevalence and 95% CI were estimated using random-effects models assuming between and within study variability. Statistical heterogeneity between results was assessed by examining forest plots and CIs, and using I2, which is the most common metric for measuring the magnitude of between-study heterogeneity, and is easily interpretable. I2 values range between 0% and 100% and are typically considered low for <25%, modest for 25–50% and high for >50%. This statistical method generally assumes heterogeneity when the p value of the I2 test is <0.05. A sensitivity analysis was thus conducted to assess the influence on the global prevalence of the inclusion and exclusion of studies. When possible (sufficient sample size), meta-regressions were proposed to study the relation between prevalence and clinically relevant parameters according to the literature. Type I-error was fixed at a=0.05.

Results

An initial search produced 9049 possible articles (figure 1). All articles that were not written in English were eliminated. Removal of duplicates and following the selection criteria reduced these articles reporting prevalence of DED in VDT workers to 16 studies.6 11 12 16–28

Quality of articles

Quality assessment of the 16 included studies was analysed by the STROBE criteria, from which results varied from 40.0% to 83.3%, with a mean score of 69.8±16.8. Overall, the studies performed best in the Methods section and worst in the Discussion section. Only three studies described ethical approval.19 25 26

Inclusion criteria for dry eye in VDT workers

DED was the shared inclusion criterion of the 16 studies.6 11 12 16–28 The diagnosis criteria for DED differed between studies and could be grouped into three categories: questionnaires on DED symptoms, tear film anomalies and corneoconjunctival epithelial damage. Questionnaires on symptoms as a diagnosis criterion was used in 13 studies,6 11 16–19 21–23 25–27 tear film anomalies evaluation in 14 studies6 11 12 16–20 23–28 and epithelial damage in 9 studies.6 11 16–19 23 24 27 Criteria were used independently or in combination. Eight studies combined two or three diagnosis criteria to identify DED.4 6 17–19 24 26 27 Moreover, the protocols and procedures associated with measurement and the thresholds applied to these different criteria also differed among studies.

Studies with symptoms as a diagnosis criterion for DED4 6 11 16–19 21 22 25–27 used different questionnaires. The most frequent questionnaire used was the Japanese dry eye diagnostic criteria.29 Only three studies used the Ocular Index Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire.11 21 25 However, the OSDI thresholds for diagnosis were, respectively, 12/100 and 23/100,11 21 and one study did not report a cut-off value.25 All questionnaires were completed by the investigator.

Assessments incorporating tear film evaluation as a criterion for diagnosis were tear break-up time (TBUT),6 11 12 16–19 23–28 Schirmer test,6 12 17–19 23–28 tear osmolarity11 26 and tear lipid layer status evaluation.12 16 As done previously, assessments could be used independently or combined, and thresholds for diagnosis varied. Among the 13 studies evaluating tear film anomalies, TBUT thresholds were considered as pathological for most. TBUT values equal or less than 5 s were used for diagnosis, with the exception of two studies, which applied a pathological value <6 s11 and <10 s.16 The Schirmer test was considered as positive in all studies for values superior or equal to 5 mm; except for one study, which cited a pathological value ≤10 mm.28 The Schirmer test was mostly performed without topical anaesthesia.6 17–19 23 25 26 Only two studies applied a topical anaesthetic prior to the Schirmer test,27 28 and two studies did not specified the use of an anaesthetic agent.12 24 Tear osmolarity cut-off values varied from 30811 to 316 mOsm/L.25 Two studies also evaluated tear lipid layer status, measuring the thickness of the superficial lipid layer of tear film ≤50 nm,16 or applying an alteration index (DR-1 grade) of 3.12

All studies diagnosing DED based on epithelial damage analysed conjunctival and/or corneal epithelium staining with fluorescein typically combined or with another vital stain: lissamine green in six studies6 17 18 23 24 or rose Bengal.19 27 Only one study used lissamine green as a unique vital stain.16

In addition, DED was defined by several criteria combined in eight studies.6 17–19 23 24 26 27 DED was described as probable or definite in seven studies based on the Japanese diagnosis criteria for DED. Specifically, DED was probable if two of the three following criteria—dry eye symptoms, tear film abnormalities and corneoconjunctival epithelial damage—were met. DED was considered as definite when all three criteria were observed. Only one study required evidence of the three criteria to diagnose a DED.25

Population

Sample size: Population sizes ranged from 5125 to 3549 individuals.22 In total, 11 365 VDT users were included in this literature review.

Gender: The proportion of males among the VDT worker population varied between 27.5%25 and 74.4%,22 but was not specified in the Brasche et al study,16 and not specified in the control group (without asthenopia) in the Nakaishi and Yamada study.20 Results were also separated for gender within DED as well as non-DED groups in seven studies.

Age: Age was not reported in most of the included studies. However, three studies6 17 18 reported age groups of DED and non-DED workers. Participants from the largest population studied ranged from 22 to 60 years of age.22

VDT using: The total time of daily VDT work and the VDT employment duration were not specified in most studies. Only six studies6 12 18 19 22 24 reported the daily duration of VDT use and only four of these reported the prevalence of DED related to this duration of VDT work.18 19 22 23 The cut-off used for the daily VDT working time was 4 h in three of these studies6 19 22 and 8 h for another.18 From the three studies, we calculated a prevalence of DED of 68.2%,19 33.4%22 and 61.6%23 in VDT users exposed to <4 h/day versus 72.1%,19 41.1%22 and 77.2%23 in VDT users exposed to >4 h/day. Combining these three studies to generate a pool of 6102 workers, we found a slightly higher prevalence of DED in VDT users with >4 h/day exposure than in VDT users with <4 h/day (61.1% vs 57.6%, χ2=0.5.72, p=0.017). A similar trend was observed in the study reporting a cut-off of 8 h of daily exposure.18 Specifically, 62.3% of VDT users with <8 h per day of exposure had a DED, compared with 85.3% for workers with >8 h of daily exposure (χ2=3.51, p=0.061).

Types of occupation: For all studies, the socioprofessional category specified was office worker6 12 16–27 or VDT operator.11 Moreover, workers included within each study were homogenous, with the same occupation, except for in one study, where individuals were enrolled in various occupations (computer operators, office workers, bank workers, teachers, tour operators and photographers).28

Outcome and aim of the studies

The prevalence of DED in VDT workers was the only reported primary outcome in five studies.21–23 27 28 The primary outcome of seven other studies was to evaluate the relationships between criteria of DED (symptoms, tear film abnormalities and epithelial damage).11 12 16 17 20 25 26 Two studies aimed to assess the impact of VDT on the lacrimal layer.19 24 The relationship between physical activity and DED was the focus of one study.18 One further study evaluated the impact of this disease on work performance and productivity in VDT workers.6

Study designs

All studies described a cross-sectional prevalence survey design, analysing DED in VDT workers, except for one study describing a prospective case–control, in which outcomes of two existing groups (contact lens vs non contact lens wearers) were compared because of a hypothesised causal attribute.19

Prevalence of DED

Within the 16 studies, the prevalence of DED in VDT workers was markedly heterogeneous with values ranging from 9.5% to 87.5%.11 12 The lowest prevalence (9.5%) was reported in the Nakamura et al study,12 which used the Schirmer test with a value inferior or equal to 5 mm to define the DED. In this same study, the use of other tear film evaluation abnormality criteria, TBUT ≤5 s and tear lipid layer status (DR-1 value) >grade 3, respectively, reported a prevalence of 49.4% and 18.1%. The highest prevalence (87.5%) was reported in one of the smallest sample size studies11 (64 VDT workers) with a DED defined by a TBUT ≤6 s. The use of other criteria in this study reported a prevalence ranging for the same population from 50.0% to 57.8%, respectively, using an OSDI score >12 and a value of tear osmolarity >308 mOsm/L. The prevalence estimated in the largest sample size study22 was 32.3% via a definition of DED that used a self-rating questionnaire of severe symptoms (dryness and irritation, constantly or often).

Meta-analysis

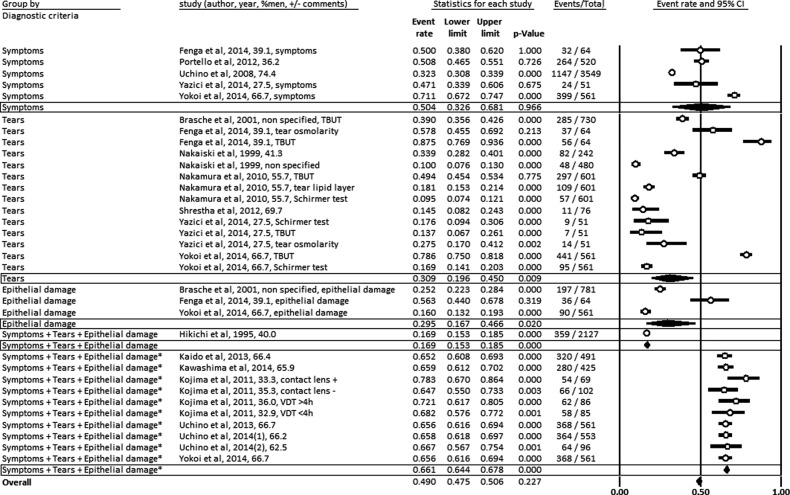

The meta-analysis was conducted on the prevalence of DED in VDT workers following the criteria used for the DED definition with data from the 16 selected studies.6 11 12 16–28 We identified a global prevalence of DED in VDT users of 49.5% (95% CI 47.5 to 50.6) with important heterogeneity (I2=98.8%, p<0.0001). Then, we stratified diagnostic criteria in the following groups: questionnaires on DED symptoms, tear film abnormalities and corneoconjunctival epithelial damage, and studies combining two or three of these diagnostic criteria. Some stratifications reported heterogeneous prevalence such as for symptoms (I2=98.7%, p<0.0001), tears (I2=98.5%, p<0.0001) and epithelial damage (I2=96.0%, p<0.0001). However, studies combining two or three diagnostic criteria reported a homogenous prevalence of 66.1% (95% CI 64.4 to 67.8, p<0.0001; I2=0%, p=0.69) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis on the prevalence of dry eye disease in visual display terminal workers stratified on the three criteria defining dry eye disease: symptoms, tear anomalies and epithelial damage.

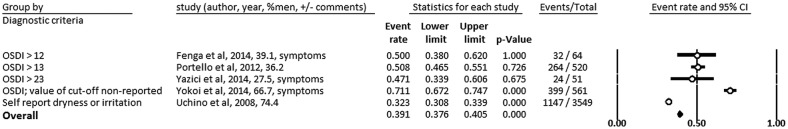

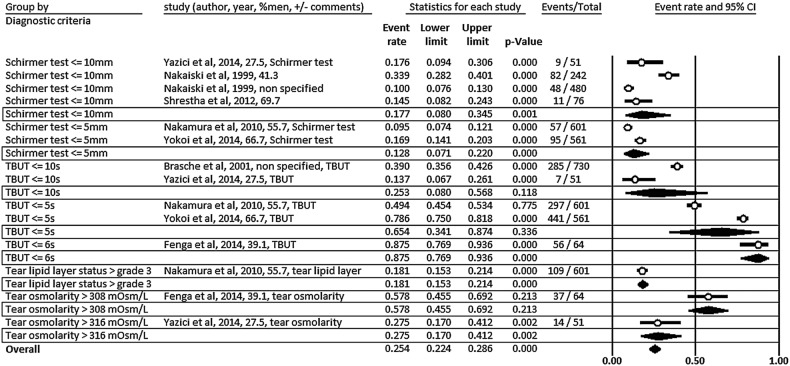

Stratification of diagnostic criteria on symptoms generated an overall prevalence of 39.1% (95% CI 37.6 to 40.5) (figure 3). Stratification of diagnostic criteria on tear film abnormalities resulted in an overall prevalence of 25.4% (95% CI 22.4 to 26.8). Prevalence appeared to decrease with restrictive cut-off criteria such as for TBUT (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis on the prevalence of dry eye disease in visual display terminal workers stratified on diagnostic criteria for symptoms. OSDI, Ocular Index Disease Index.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis on the prevalence of dry eye disease in visual display terminal workers stratified on diagnostic criteria for tear film abnormalities. TBUT, tear break-up time.

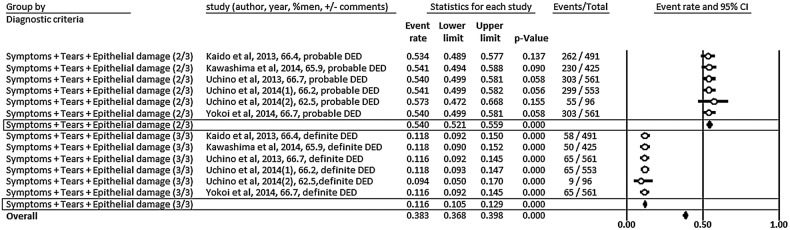

An insufficient number of studies limited any stratification using epithelial damage. Within stratification of studies combining several diagnostic criteria, the overall prevalence was 38.3% (95% CI 36.8 to 39.8) with an impact of the number of criteria for diagnosis. Stratification of studies with two criteria retrieved a prevalence of 54.0% (95% CI 52.1 to 55.9), whereas studies using three criteria retrieved a prevalence of 11.6% (95% CI 10.5 to 12.9). The prevalence was homogeneous for studies combing two and three criteria (I2=0%, p=0.99) (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis on the prevalence of DED in visual display terminal workers stratified on combining several diagnostic criteria. DED, dry eye disease.

Meta-regressions

We demonstrated an increased prevalence of DED with age (coefficient 5.05, 95% CI 1.98 to 8.12, p=0.003) and for female gender (coefficient 0.14, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.24, p=0.010) (table 1). Insufficient sample sizes precluded other meta-regressions.

Table 1.

Correlation between DED prevalence and worker characteristics (gender and age)

| Variables | Correlation coefficient | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | −0.137 | (−0.239 to −0.036) | 0.010 |

| Age | 5.054 | (1.985 to 8.124) | 0.003 |

DED, dry eye disease.

Discussion

Sixteen studies met our inclusion criteria for examining the prevalence of DED in VDT users. The major finding was that the prevalence of DED in office workers was difficult to estimate, with values ranging from 9.5% to 87.5% in a total population of more than 10 000 workers. Owing to the disparity of the diagnosis criteria used to define DED, the global prevalence of 49.5% (95% CI 47.5 to 50.6) was not relevant because of the substantial heterogeneity (I2=98.8%, p<0.0001). Thus, we highlight the necessity of implementing common DED diagnostic criteria to allow a more relevant estimation in order to develop the appropriate preventive occupational actions. Standardisation of criteria should be accepted on an international scale based on the DEWS review published in 2007 and other recent initiatives (Uchino et al).

Heterogeneity of DED diagnosis criteria and pathological thresholds

We highlighted wide variations of prevalence from 9.5% to 87.5%. We demonstrated that heterogeneity was linked with diagnostic criteria. Symptoms, tear film abnormalities and epithelial damage were the identified diagnosis criteria for all retrieved studies. Intuitively, the less restrictive diagnosis criteria were, the more prevalence increased. The number of diagnostic criteria used to define DED also provided a trend; studies combining several criteria demonstrated a higher prevalence. The prevalence also increased in studies identifying DED from tear film abnormalities, which can be described as less restrictive diagnosis criteria than questionnaires on symptoms or corneoconjunctival epithelial damage.26 30 31 Surprisingly, in the limited number of studies in which DED symptoms were assessed via questionnaires, when cut-off levels were made more discriminative, a similar proportion of DED was reported. The ability of patients to correctly recall their symptoms may be an explanation.32 Even though epithelial damage could have intuitively produced a more reliable and standardised diagnosis, the only two studies solely assessing DED on this criteria showed considerable variation. Therefore, we vigorously promote international guidelines for DED diagnostic criteria. At a national level, the Japanese research teams’ work is nevertheless remarkable, especially the Osaka study, for addressing the need to standardise the DED diagnostic criteria and evaluation method in the workplace. In these studies,6 17–19 23 24 26 we observed that DED prevalence was relatively homogeneous. Although homogeneity within Japanese publications could be explained by the use of similar DED diagnosis criteria and methodology, the underlying hypothesis of international reform could not be disregarded because of widespread heterogeneity of studies elsewhere in the world. DED should be assessed more consistently and further investigations may include assessing genetic susceptibility of DED.

DED in the worker population

DED is an underestimated health concern in the workplace, with direct consequences of workplaces completely devoid of preventative strategies. Indeed, DED is responsible for considerable discomfort at work for the employee and a loss of productivity for companies. Identified risk factors for DED include: age, female sex, certain medications, wearing contact lenses, eyelid infection, smoking, refractive surgery, extreme hot or cold weather conditions, low relative humidity and exposure to VDT.33

Within this systematic review of workers, an increased prevalence of DED was apparent with age and for female gender.10 Despite significant results with the use of χ2, establishing a higher prevalence of DED with duration of exposure to VDT use, the number of studies assessing the influence of time of exposure was too low to permit meta-regression on this parameter. Also, insufficient data precluded meta-regression analyses with others parameters; especially with individual risk factors already established (smoking, ocular and eyelid diseases, contact lenses wear, medications) and other work-related parameters that remain unclear (hours exposed to VDT daily, temperature and humidity in the workplace, and employment duration).

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. To assess effects of VDT work, it would have been interesting to compare the prevalence of DED in VDT users to the prevalence of DED in the general population, however, no studies compared the diagnosis of DED in VDT users to that of a control group, within the same studies, and therefore with the same diagnosis criteria. We can only note that our retrieved prevalence in VDT users (50%) seems greater than the prevalence in the general population (5–33%).10 Even though DED may be considered a chronic condition affecting the ocular surface, we did not retrieve studies addressing the issue of workers experiencing discomfort towards the end of the day. Furthermore, populations investigated in the meta-analysis appear to be clustered from specific countries of the world. Two studies were on European workers,11 16 one was in Nepal28 and one in the USA,21 whereas the remaining research was conducted exclusively in Japan. The use of broader keywords in the search strategy may have resulted in a wider potential of articles. However, we already included most of the articles on DED in VDT users. Most importantly, we believe that the key message of our article is not altered. The heterogeneity of the DED diagnostic criteria and their measurement as well as the pathological threshold definition applied may explain the large variability in the prevalence reported. Results from the meta-analysis are therefore inconclusive. However, we demonstrated greater homogeneity of prevalence with shared diagnosis criteria and therefore strengthened the need for a common widely standardised definition.

Conclusion

VDT work has been increasing in offices and a large number of workers experience symptoms associated with VDT use. The usage is especially associated with DED, but the prevalence is probably widely underestimated. Nevertheless, DED in VDT users has important consequences for employees and the employer because it causes VDT users distress at work and may compromise workplace productivity. We demonstrated that, in approximately 10 000 VDT workers, the estimation of prevalence of DED was widely heterogeneous with values widely scattered—from 9.5% to 87.5%. Thus, we strengthen the evidence for establishing common DED diagnostic criteria to allow more accurate estimation. Universal agreement and implementation of diagnostic criteria for DED would support the development of appropriate preventive occupational strategies and collectively contribute to advancing the understanding of DED risk in the workplace. Agreement could be guided by previous initiatives (DEWS, Uchino et al) but should include more than one criterion and should perhaps include more frequent assessment for workers already known to be at risk of DED.

Footnotes

Contributors: FD was responsible for the design and conception of the study. RC, BP and FD analysed and interpreted the data. RC and FD wrote the manuscript. RC and FD collected the data. BP was responsible for the statistical expertise. RC and FD completed the literature search. All the authors made critical revisions and gave final approval to the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Brewitt H, Sistani F. Dry eye disease: the scale of the problem. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;45:S199–202. 10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00202-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grubbs JR Jr, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Huynh K et al. A review of quality of life measures in dry eye questionnaires. Cornea 2014;33:215–18. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA et al. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:409–15. 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchino M, Schaumberg DA. Dry eye disease: Impact on quality of life and vision. Curr Ophthalmol Rep 2013;1:51–7. 10.1007/s40135-013-0009-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pflugfelder SC. Prevalence, burden, and pharmacoeconomics of dry eye disease. Am J Manag Care 2008;14:S102–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchino M, Uchino Y, Dogru M et al. Dry eye disease and work productivity loss in visual display users: the osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:294–300. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada M, Mizuno Y, Shigeyasu C. Impact of dry eye on work productivity. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2012;4:307–12. 10.2147/CEOR.S36352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel VD, Watanabe JH, Strauss JA et al. Work productivity loss in patients with dry eye disease: an online survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:1041–8. 10.1185/03007995.2011.566264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan BD, Crews LA, Messmer EM et al. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:161–6. 10.1111/aos.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.[No authors listed] The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the epidemiology subcommittee of the international dry eye workshop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5:93–107. 10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70082-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenga C, Aragona P, Di Nola C et al. Comparison of ocular surface disease index and tear osmolarity as markers of ocular surface dysfunction in video terminal display workers. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;158:41–8. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura S, Kinoshita S, Yokoi N et al. Lacrimal hypofunction as a new mechanism of dry eye in visual display terminal users. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e11119 10.1371/journal.pone.0011119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Costa BR, Cevallos M, Altman DG et al. Uses and misuses of the strobe statement: Bibliographic study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000048 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:W163–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ollier M Jr, Chamoux A, Naughton G et al. Chest computed tomography screening for lung cancer in asbestos occupational exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2014;145:1339–46. 10.1378/chest.13-2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasche S, Bullinger M, Bronisch M et al. Eye- and skin symptoms in German office workers—subjective perception vs. Objective medical screening. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2001;203:311–16. 10.1078/1438-4639-00042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaido M, Uchino M, Yokoi N et al. Dry-eye screening by using a functional visual acuity measurement system: the Osaka study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:3275–81. 10.1167/iovs.13-13000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawashima M, Uchino M, Yokoi N et al. The association between dry eye disease and physical activity as well as sedentary behavior: results from the Osaka study. J Ophthalmol 2014;943786:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kojima T, Ibrahim OM, Wakamatsu T et al. The impact of contact lens wear and visual display terminal work on ocular surface and tear functions in office workers. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152:933–40 e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakaishi H, Yamada Y. Abnormal tear dynamics and symptoms of eyestrain in operators of visual display terminals. Occup Environ Med 1999;56:6–9. 10.1136/oem.56.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portello JK, Rosenfield M, Bababekova Y et al. Computer-related visual symptoms in office workers. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2012;32:375–82. 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2012.00925.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchino M, Schaumberg DA, Dogru M et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease among Japanese visual display terminal users. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1982–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchino M, Yokoi N, Uchino Y et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease and its risk factors in visual display terminal users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:759–66. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchino Y, Uchino M, Yokoi N et al. Alteration of tear mucin 5ac in office workers using visual display terminals: the Osaka study. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:985–92. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yazici A, Sari ES, Sahin G et al. Change in tear film characteristics in visual display terminal users. Eur J Ophthalmol 2015;25:85–9. 10.5301/ejo.5000525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoi N, Uchino M, Uchino Y et al. Importance of tear film instability in dry eye disease in office workers using visual display terminals: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:748–54. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Fukui Y et al. Prevalence of dry eye in Japanese eye centers. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1995;233:555–8. 10.1007/BF00404705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrestha G, Mohamed F, Shah D. Visual problems among video display terminal (VDT) users in Nepal. J Optom 2011;4:56–62. 10.1016/S1888-4296(11)70042-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimazaki J, Tsubota K, Kinoshita S et al. Definition and diagnosis of dry eye 2006. Atarashii Ganka 2007;24:181–4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bron AJ, Tomlinson A, Foulks GN et al. Rethinking dry eye disease: a perspective on clinical implications. Ocul Surf 2014;12:S1–31. 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downie LE, Keller PR. A pragmatic approach to dry eye diagnosis: evidence into practice. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92:957–66. 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardona G, Marcellán C, Fornieles A et al. Temporal stability in the perception of dry eye ocular discomfort symptoms. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87:1023–9. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181ff99ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol 2009;3:405–12. 10.2147/OPTH.S5555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]