Abstract

Objectives

To clarify the association between toothbrushing and risk factors for cardiovascular disease—namely, hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidaemia (DL), hyperuricaemia (HUA) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design

A large-scale, single-centre, cross-sectional study.

Setting

St Luke's International Hospital, Center for Preventive Medicine, Tokyo, Japan, between January 2004 and June 2010.

Participants

This study examined the toothbrushing practices of 85 866 individuals according to the 3-category frequency criterion: ‘after every meal’, ‘at least once a day’ and ‘less than once a day’. The ORs by frequency were calculated for the prevalences of HT, DM, DL, HUA and CKD according to binominal logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, gender, body mass index and lifestyle habits—smoking, drinking, walk time and sleep time.

Results

The prevalences of the risk factors were as follows: HT (‘after every meal’: 13.3%, ‘at least once a day’: 17.9% and ‘less than once a day’: 31.0%), DM (3.1%, 5.3% and 17.4%, respectively), DL (29.0%, 42.1% and 60.3%, respectively), HUA (8.6%, 17.5% and 27.2%, respectively) and CKD (3.8%, 3.1% and 8.3%, respectively). The prevalences were significantly higher in the ‘less than once a day’ group than in the ‘after every meal’ group for DM (OR=2.03; 95% CI 1.29 to 3.21) and DL (OR=1.50; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.14), but not for HT, HUA and CKD.

Conclusions

Even taking into account lifestyle habits, a lower frequency of toothbrushing was associated with high prevalences of DM and DL. Toothbrushing practices may be beneficial for oral health improvement and also for prevention of certain systemic diseases.

Keywords: Toothbrushing, Diabetes mellitus, Dyslipidemia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large-scale, cross-sectional Japanese study to clarify the association between toothbrushing practices and risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

This study used binominal logistic regression analyses adjusted for lifestyle habits—smoking, drinking, walk time and sleep time.

Even taking into account lifestyle habits, a low frequency of toothbrushing was significantly associated with the high prevalences of diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia, but not with hypertension, hyperuricaemia and chronic kidney disease.

A limitation of the study is residual selection bias due to a single-centre study.

Introduction

Good oral hygiene, in which toothbrushing has a central role,1 is important to prevent gingivitis and tooth decay. Some toothbrushing intervention programmes have shown promising results in reducing dental plaque formation.2 However, the extent of association between toothbrushing practices and cardiovascular disease remains unknown. Poor oral hygiene was associated with higher levels of risk for cardiovascular disease in a study conducted by de Oliveira et al.3 However, Yeung4 pointed out that the study had not determined the causality between oral hygiene and cardiovascular disease because of biased health consciousness. Recent studies reported that a low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with endothelial dysfunction5 and that an improvement in periodontal status prevented intima-media thickness progression in the carotid arteries.6 Daily toothbrushing was shown to be related to a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT) and dyslipidaemia (DL).7 Furthermore, a higher frequency of toothbrushing was found to be associated with a higher rate of good diabetes control in patients with DM.8 9 However, these mechanisms were unclear, but there was a report that a low frequency of toothbrushing facilitated the proliferation of Porphyromonas gingivalis. P. gingivalis proliferates in the presence of increased insulin resistance and systemic inflammation, with the alteration of gut microbiota.10 Increased insulin resistance and systemic inflammation also cause DM.

A great number of people, especially the elderly, are still affected by cardiovascular disease despite recent advances in medical knowledge and technology. Therefore, there is an increasing need to implement public health measures, including oral hygiene, to enable them to acquire healthier lifestyle habits. Toothbrushing is one of the most familiar and easiest methods of improving oral hygiene in the general population. Based on the possible link between dental disease and cardiovascular disease,11 toothbrushing may be an easily applicable preventive method for cardiovascular disease.

We conducted this epidemiological study to examine the association between frequency of toothbrushing and risk factors for cardiovascular disease—HT, DM, DL, hyperuricaemia (HUA) and chronic kidney disease (CKD)—in addition to considering lifestyle habits of the healthy general population.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This large-scale, single-centre, epidemiological study of cross-sectional design retrospectively analysed the medical records of 90 143 individuals who had undergone an annual medical checkup at St Luke's International Hospital Center for Preventive Medicine, Tokyo, Japan, between January 2004 and June 2010. This centre for preventive medicine conducted a conventional medical check-up. This medical system has ideal conditions for clinical measurements. These records used data only from the first visit between January 2004 and June 2010, so that participants who had more than one annual check-up during these periods were not double counted. Our previous study used this database and methods in a similar way to the present study.12

Of the 90 143 individuals, 85 866 people, aged 30–84, were analysed. Individuals arriving at our hospital, submitted a self-administered questionnaire including details of toothbrushing practices. The study population was split into the following three groups according to their toothbrushing practices: ‘after every meal’, ‘at least once a day’ and ‘less than once a day’. The prevalences of risk factors for cardiovascular disease—HT, DM, DL, HUA and CKD—were calculated in each group.

The smoking subgroup comprised individuals who had a current or past history of smoking. The drinking subgroup was composed of individuals with a drinking habit and did not include non-habitual drinkers. Walk time and sleep time were calculated based on information provided by the self-administered questionnaire.

Blood pressure (BP) was recorded using an automatic brachial sphygmomanometer (OMRON Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). BPs of each person were measured twice—after sitting and remaining quiet for >5 min, with the feet on the ground and the back supported. The mean values of systolic and diastolic BP of each person were calculated from the recorded measurements. HT was defined as a systolic BP of ≥140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic BP of ≥90 mm Hg. DL was defined as a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of ≥140 mg/dL, a high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of <40 mg/dL or a triglyceride level of ≥150 mg/dL. DM was defined as a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration of ≥6.5% (according to the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program). HUA was defined as a serum uric acid concentration of >7.0 mg/dL. CKD was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The HT, DL, DM and HUA subgroups included patients who were followed up and who received medication for their diseases.

Ethical considerations

All data were collected and held in a password-protected computer database. Individual data were anonymised. St Luke's International Hospital ethics committee approved the use of these data and the protocol for this study (approval number: 14-R033; 30 June 2014).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc method was conducted to compare the characteristics and lifestyle habits of individuals among the three groups. Statistical differences in toothbrushing between the groups were evaluated using binominal logistic regression models, with the ‘after every meal’ group as reference. Binominal logistic regression analyses were conducted, adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), HT, DM, DL, HUA and CKD, and for lifestyle habits— smoking, drinking, walk time and sleep time. A value of p<0.05, two-sided, was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics software (IBM SPSS Statistics V.19 for Windows; IBM, New York, New York, USA).

Results

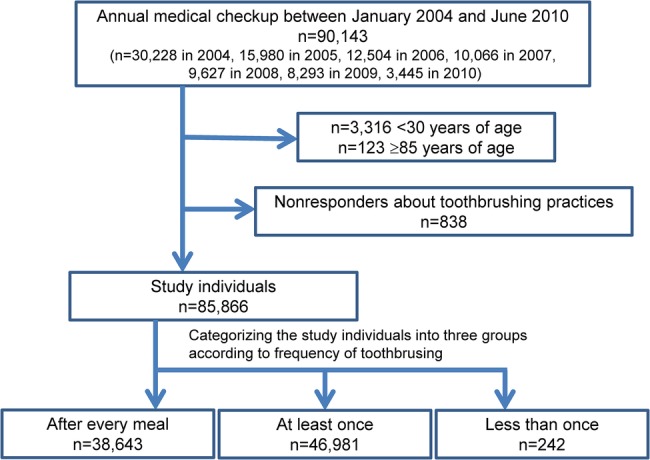

This study analysed the medical records of 90 143 individuals (men: 49.1%; age, mean±SD 46.3±12.0 years) who had undergone annual medical checkup between January 2004 and June 2010; 30 228 individuals in 2004, 15 980 individuals in 2005, 12 504 individuals in 2006, 10 066 individuals in 2007, 9627 individuals in 2008, 8293 individuals in 2009 and 3445 individuals in 2010 were enrolled. Of them, 85 866 (men: 49.0%; mean±SD age: 47.0±11.5 years) met the inclusion criteria for this study. The following individuals were excluded: 3316 <30 years of age; 123 ≥85 years of age; and 838 non-responders about toothbrushing practices. Individuals were categorised according to the three-category toothbrushing frequency criterion: 38 643 (45.0%)—‘after every meal’, 46 981 (54.7%)—‘at least once a day’ and 242 (0.3%)—‘less than once a day’ (figure 1). Among individual characteristics, low frequency of toothbrushing was significantly (p<0.001) associated with older age, the higher prevalence of male gender, greater height, greater weight, higher BMI, larger abdominal circumference, higher BP and lower pulse rate (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study enrollment.

Table 1.

Individual characteristics

| Characteristics | Overall | Frequency of toothbrushing per day |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After every meal | At least once | Less than once | |||

| (n=85 866) | (n=38 643) | (n=46 981) | (n=242) | ||

| Age, years | 47.0±11.5 | 46.4±11.6 | 47.4±11.4 | 51.7±15.0 | <0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 49.0 | 32.7 | 62.2 | 92.6 | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 164.2±8.6 | 162.3±8.2 | 165.9±8.7 | 168.5±7.3 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 60.9±11.2 | 57.3±11.2 | 63.8±12.5 | 71.6±13.2 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.4±3.3 | 21.6±3.1 | 23.1±3.4 | 25.1±3.9 | <0.001 |

| AC, cm | 80.3±10.3 | 78.0±10.9 | 82.2±9.4 | 88.8±10.4 | <0.001 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 117.7±17.4 | 115.5±17.3 | 119.4±17.3 | 126.9±11.7 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 73.2±11.2 | 71.7±11.1 | 74.3±11.2 | 77.9±10.6 | <0.001 |

| PR, bpm | 73.9±10.9 | 74.3±10.9 | 73.5±10.8 | 72.9±11.8 | <0.001 |

Values are expressed as mean±SD.

AC, abdominal circumference; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PR, pulse rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

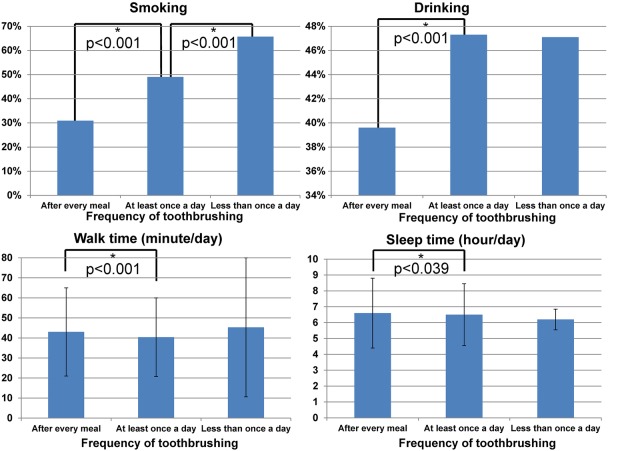

Lifestyle habits—that is, smoking, drinking, walk time and sleep time, were associated with frequency of toothbrushing. A low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with heavy smoking (‘after every meal’: 30.9%, ‘at least once a day’: 49.0%, ‘less than once a day’: 65.7%), heavy drinking (‘after every meal’: 39.6%, ‘at least once a day’: 47.3% and ‘less than once a day’: 47.1%), short walk time (mean±SD ‘after every meal’: 43.0±44.0 min, ‘at least once a day’: 40.4±39.3 min, ‘less than once a day’: 45.3±69.5 min) and short sleep time (mean±SD ‘after every meal’: 6.6±4.4 h, ‘at least once a day’: 6.5±3.9 h, ‘less than once a day’: 6.2±1.3 h). ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc method showed that significant differences between groups were mostly between ‘after every meal’ and the ‘at least once a day’ categories and differed significantly between the ‘at least once a day’ and the ‘less than once a day’ category only for smoking (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lifestyle habits and frequency of toothbrushing practices. *Significant difference between the groups (p<0.05 between groups by analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc method).

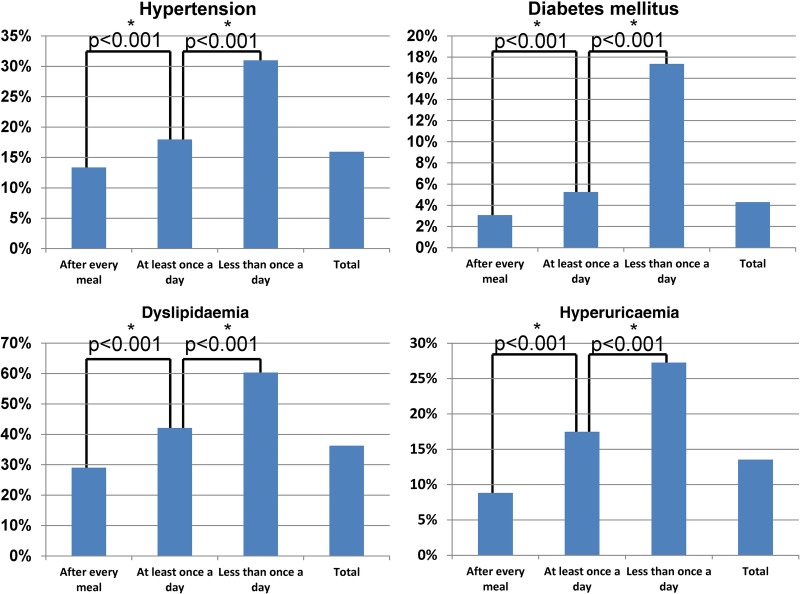

A low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with high prevalences of HT (‘after every meal’: 13.3%, ‘at least once a day’: 17.9% and ‘less than once a day’: 31.0%), DM (3.1%, 5.3% and 17.4%, respectively), DL (29.0%, 42.1% and 60.3%, respectively), HUA (8.6%, 17.5% and 27.2%, respectively) and CKD (3.8%, 3.1% and 8.3%, respectively). ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc method indicated that differences between the groups were statistically significant: HT (OR=1.34 for ‘at least once a day’ against ‘after every meal’ and OR=2.32 for ‘less than once a day’ against ‘after every meal’; p<0.001), DM (1.71 and 5.65, respectively; p<0.001), DL (1.45 and 2.08, respectively; p<0.001), HUA (1.98 and 3.09, respectively; p<0.001) and CKD (0.82 and 2.18; p<0.001) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease and frequency of toothbrushing practices. Analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc method indicated that differences between the groups were statistically significant: hypertension (OR=1.34 for ‘at least once a day’ against ‘after every meal’ and OR=2.32 for ‘less than once a day’ against ‘after every meal’; p<0.001); diabetes mellitus (1.71 and 5.65, respectively; p<0.001); dyslipidaemia (1.45 and 2.08, respectively; p<0.001); and hyperuricaemia (1.98 and 3.09, respectively; p<0.001). *Significant difference between the groups (p<0.05 between groups by analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc method).

In binominal logistic regression analyses, the prevalence of DM increased significantly with low frequency of toothbrushing (OR=1.17 and 95% CI 1.07 to 1.29 for ‘at least once a day’ against ‘after every meal’; OR=2.03 and 95% CI 1.29 to 3.21 for ‘less than once a day’ against ‘after every meal’). The prevalence of DL showed the similar changes: (OR=1.18 and 95% CI 1.14 to 1.23 for ‘once a day’ against ‘after every meal’; OR=1.50 and 95% CI 1.06 to 2.14 for ‘less than once a day’ against ‘after every meal’). No statistically significant differences were found between the three groups for HT, HUA and CKD (table 2).

Table 2.

Binominal logistic regression analyses on frequency of toothbrushing and risk factors for cardiovascular disease

| Toothbrushing | Prevalence (disease/total) | % | Crude |

Adjusted* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |||

| Hypertension | |||||||

| After every meal | 5158/38 642 | 13.3 | (reference) | (reference) | |||

| At least once a day | 8430/46 980 | 17.9 | 1.34 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.94 to 1.05 | 0.837 |

| Less than once a day | 75/242 | 31.0 | 2.32 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.60 to 1.33 | 0.579 |

| Total | 13 663/85 864 | 15.9 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||

| After every meal | 1188/38 642 | 3.1 | (reference) | (reference) | |||

| At least once a day | 2468/46 977 | 5.3 | 1.71 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.07 to 1.29 | 0.001 |

| Less than once a day | 42/242 | 17.4 | 5.65 | <0.001 | 2.03 | 1.29 to 3.21 | 0.002 |

| Total | 3698/85 861 | 4.3 | |||||

| Dyslipidaemia | |||||||

| After every meal | 11 221/38 642 | 29.0 | (reference) | (reference) | |||

| At least once a day | 19 778/46 978 | 42.1 | 1.45 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.14 to 1.23 | <0.001 |

| Less than once a day | 146/242 | 60.3 | 2.08 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 1.06 to 2.14 | 0.023 |

| Total | 31 145/85 862 | 36.3 | |||||

| Hyperuricaemia | |||||||

| After every meal | 3341/38 643 | 8.6 | (reference) | (reference) | |||

| At least once a day | 8206/46 981 | 17.5 | 1.98 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.02 to 1.15 | 0.011 |

| Less than once a day | 66/242 | 27.3 | 3.09 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.60 to 1.26 | 0.446 |

| Total | 11 613/85 866 | 13.5 | |||||

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||||

| After every meal | 1464/38 643 | 3.8 | (reference) | (reference) | |||

| At least once a day | 1454/46 981 | 3.1 | 0.82 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 0.77 to 1.14 | 0.482 |

| Less than once a day | 20/242 | 8.3 | 2.18 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 0.38 to 4.72 | 0.642 |

| Total | 2938/85 866 | 3.4 | |||||

*Adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, hyperuricaemia and chronic kidney disease, and also for lifestyle habits—smoking, drinking, walk time and sleep time.

Discussion

This large-scale epidemiological study provides a highly-quality medical record database because of the low exclusion rate. Adjusted binominal logistic regression analyses showed that a low frequency of toothbrushing was significantly associated with the high prevalences of DM (OR=2.03) and DL (OR=1.50), but not with HUA and CKD. This suggests the involvement of DM and DL, associated with a low frequency of toothbrushing, in cardiovascular disease.

A previous study showed that a low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with hypertriglyceridaemia only and that more frequent toothbrushing was associated with a low prevalence of metabolic syndrome.13 Another study indicated that a low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with high prevalences of DM, DL and HT,7 which is in agreement with our study for DM and DL; the prevalences of raised BP and HT were significantly higher with a low frequency of toothbrushing than with a high frequency. However, the previous study did not examine renal function and sleep time, which may explain the difference between the studies. Our present study provides a higher quality of research because it examines a greater number of lifestyle-related variables.

There are two possible reasons why a low frequency of toothbrushing is associated with DM and DL. One is that periodontal disease causes DM and DL. A low frequency of toothbrushing increases periodontal disease,1 and this disease is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease14 15 and DM.16 17 However, the causality between periodontal disease and DL remains controversial: both contrary18 and positive19 results have been published. The other theory is that DM and DL are strongly associated with P. gingivalis—a major pathogenic bacterium of periodontal disease. A low frequency of toothbrushing facilitates the proliferation of P. gingivalis. Furthermore, DL impairs the innate immune response to P. gingivalis20 that proliferates in cases of increased insulin resistance and systemic inflammation, with the alteration of gut microbiota.10 Increased insulin resistance and systemic inflammation also cause DM and DL. These theories can also explain why a low frequency of toothbrushing is associated with endothelial dysfunction.5

This study has several limitations. First, the study has a possible residual selection bias as it is a single-centre study, but all data were well-controlled and reported. A cohort and multicenter study is expected. Second, this study could not assess the duration and details of toothbrushing (eg, use of dental floss, interdental cleansers and water irrigation under pressure). Nevertheless, we consider that this study strictly considered possible confounding factors— age, gender, BMI, HT, DM, DL, HUA and CKD, and also lifestyle habits (smoking, drinking, walk time and sleep time). Third, the ‘less than once a day’ group was much smaller than the other two groups, comprising only 242 participants. Fourth, the ‘less than once a day’ group was composed of almost completely male participants (>90%) and we conducted logistic regression analyses adjusted for gender. Fifth, this study could not evaluate the association between toothbrushing and the incidence of cardiovascular disease. A previous study reported that a low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease,3 but our study focused on the association between toothbrushing and the risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

Our study confirmed that, even when considering lifestyle habits, a low frequency of toothbrushing was associated with the prevalences of DM and DL in a large adult general population, which possibly explains the association of toothbrushing with cardiovascular disease. A longitudinal cohort study will be needed to confirm whether toothbrushing prevents DM and DL.

Even when taking into account lifestyle habits, a lower frequency of toothbrushing was associated with high prevalences of DM and DL. Better toothbrushing practices may be beneficial for oral health improvement and for prevention of certain systemic diseases.

Acknowledgments

All the authors of this paper fulfil the criteria of authorship. The authors thank all staff in the Center for Preventive Medicine, St Luke’s International Hospital, for assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: all authors. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: MK, YMot, KI, MF, CI, HS, KK and YN. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: MK, YMot, HS and YN. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from Clinical and Epidemiologic Research of the Joint Project of the Japan Heart Foundation and the Japanese Society of Cardiovascular Disease Prevention sponsored by AstraZeneca. The sponsor had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data and in the writing of the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: St Luke's International Hospital ethics committee approved the protocol for this study (approval number: 14-R033; 30 June 2014).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Glickman I. Periodontal disease. N Engl J Med 1971;284:1071–7. 10.1056/NEJM197105132841906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefanovska E, Nakova M, Radojkova-Nikolovska V et al. Tooth-brushing intervention programme among children with mental handicap. Bratisl Lek Listy 2010;111:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Oliveira C, Watt R, Hamer M. Toothbrushing, inflammation and risk of cardiovascular disease: results from Scottish Health Survey. BMJ 2010;340:c2451 10.1136/bmj.c2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeung CA. Gums and heart disease. Healthy gums, healthy heart? BMJ 2010;341:c3710 10.1136/bmj.c3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kajikawa M, Nakashima A, Maruhashi T et al. Poor oral health, that is, decreased frequency of tooth brushing, is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Circ J 2014;78:950–4. 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Jacobs DR et al. Changes in clinical and microbiological periodontal profiles relate to progression of carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology study. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000254 10.1161/JAHA.113.000254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita M, Ueno K, Hata A. Lower frequency of daily teeth brushing is related to high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:387–94. 10.3181/0809-RM-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal A, Panat SR. Oral health behavior and HbA1c in Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. J Oral Sci 2012;54:293–301. 10.2334/josnusd.54.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merchant AT, Oranbandid S, Jethwani M et al. Oral care practices and A1c among youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J Periodontol 2012;83:856–63. 10.1902/jop.2011.110416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H et al. Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota. Sci Rep 2014;4:4828 10.1038/srep04828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persson GR, Persson RE. Cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: an update on the associations and risk. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35(8 Suppl):362–79. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwabara M, Niwa K, Nishi Y et al. Relationship between serum uric acid levels and hypertension among Japanese individuals not treated for hyperuricemia and hypertension. Hypertens Res 2014;37:785–9. 10.1038/hr.2014.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi Y, Niu K, Guan L et al. Oral health behavior and metabolic syndrome and its components in adults. J Dent Res 2012;91:479–84. 10.1177/0022034512440707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahekar AA, Singh S, Saha S et al. The prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J 2007;154:830–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howell TH, Ridker PM, Ajani UA et al. Periodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in U.S. male physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:445–50. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01130-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvi GE, Carollo-Bittel B, Lang NP. Effects of diabetes mellitus on periodontal and peri-implant conditions: update on associations and risks. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35(8 Suppl):398–409. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavarry NG, Vettore MV, Sansone C et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and destructive periodontal disease: a meta-analysis. Oral Health Prev Dent 2009;7:107–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almeida Abdo J, Cirano FR, Casati MZ et al. Influence of dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus on chronic periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2013;84:1401–8. 10.1902/jop.2012.120366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pejcic A, Kesic L, Brkic Z et al. Effect of periodontal treatment on lipoproteins levels in plasma in patients with periodontitis. South Med J 2011;104:547–52. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182242eaa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei L, Li H, Yan F et al. Hyperlipidemia impaired innate immune response to periodontal pathogen porphyromonas gingivalis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e71849 10.1371/journal.pone.0071849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]