Abstract

Objective

Adolescent substance use is an area of concern because early substance use is associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes. Parenting style, defined as the general style of parenting, as well as substance-specific parenting practices may influence children's substance use behaviour. The present study aims to probe the impact of parenting style on adolescent substance use.

Method

A cohort of 1268 adolescents (48% girls), aged 12–13 years at baseline, from 21 junior high schools was assessed in the first semester of junior high school, and then again in the last semester of the 9th grade, 32 months later. Parenting style, operationalised as a fourfold classification of parenting styles, including established risk factors for adolescent substance use, were measured at baseline.

Results

Neglectful parenting style was associated with worse substance use outcomes across all substances. After adjusting for other proximal risk factors in multivariate analyses, parenting style was found to be unrelated to substance use outcomes with one exception: authoritative parenting style was associated with less frequent drinking. Association with deviant peers, delinquent behaviour, provision of alcohol by parents, and previous use of other substances were associated with substance use outcomes at follow-up.

Conclusions

The results of the present study indicate that parenting style may be less important for adolescent substance use outcomes than what has previously been assumed, and that association with deviant peers and delinquent behaviour may be more important for adolescent substance use outcomes than general parenting style.

Keywords: Adolescents, Substance use, Alcohol, Cannabis, Tobacco, Parenting styles

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large sample, followed prospectively during the course of over 2 years.

General parenting styles as well as several established risk factors for adolescent substance use are measured at baseline.

High response rates in adolescents.

Peer substance use not assessed separately, only together with other deviant behaviours.

Participating schools are not randomly selected and may not be representative of the general junior high school population.

Attrition rate and missing data not handled by imputation, though by sensitivity analysis and post-stratification weighting by census data.

Introduction

Adolescents who initiate substance use at an early age are at increased risk of substance use disorders, poor academic performance and impaired social functioning.1–4 Preventing or delaying onset of substance use in adolescents is a concern among public health professionals and researchers. A basic task in refining prevention programmes is to identify risk factors for early onset of substance use. It is thus important to study pathways to adolescent substance use in order to facilitate development of prevention programmes.

In the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Drugs, survey from 2011 estimated that 87% of European adolescents aged 15–16 years had ever used alcohol, 54% cigarettes and 18% illicit drugs, including cannabis. Among Swedish adolescents in the age range 15–16 years, 46% reported alcohol use in the past year, 14% were cigarette smokers, and 8% reported lifetime illicit drug use.5

Parental alcohol use, attitudes to adolescent drinking, and supervised drinking have repeatedly been shown to increase unsupervised drinking and other drug use in adolescents.6–9 However, not only substance-specific parenting practices are of importance, but general aspects of parenting may also contribute to the adolescents’ propensity to engage in substance use. In the 60s, Baumrind identified three major parenting styles based on two important aspects of parenting: responsiveness (the degree to which parents are responsive and warm to the child) and demandingness (the degree to which the parents expect mature behaviour, and exert control over the child).10 The parenting styles identified by Baumrind which encompassed the majority of families were: authoritative, being responsive to the child’s feelings and needs while also being demanding; authoritarian, being controlling with beliefs that child should be kept in place; and permissive, accepting and non-punitive, with few demands on the children. Maccoby and Martin11 extended this model by separating neglectful parenting, characterised by low demandingness and low responsiveness, from permissive parenting, and thus introduced a fourfold classification of parenting styles based on the four combinations of high/low on the aspects responsiveness and demandingness. This classification has become widely used in the context of adolescent substance use.12

A recent review shows that most studies find that authoritative parenting is associated with the best outcomes regarding adolescent substance use, and neglectful parenting with the worst.12 Specifically, many studies have shown that authoritative parenting is associated with less use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs in children and adolescents.12–16 Children of authoritarian parents generally report more substance use than children of authoritative parents, but some studies found no difference or even an inverse association.12 Findings related to the permissive parenting style are mixed; some studies have shown that permissive parenting is associated with higher rates of substance use, while others demonstrate the opposite association.13 14 17 Neglectful parenting style is almost consistently found to be associated with higher rates of substance use.13 14 17 A recent review called for more longitudinal research on this topic as most previous studies were cross-sectional, and also because the cultural context may influence associations between parenting style and substance use.12 13 18–21 Also, few previous longitudinal studies control for other aspects such as peers, delinquency and parental substance use, all of which may influence associations between parenting styles and substance use.

Having substance-using and deviant peers has been acknowledged as an important predictor of adolescent substance use,22–24 and the influence of peers seems to be greater than that of parents.25 Other well known predictors for adolescent substance use are personal characteristics, such as disinhibition, novelty seeking and delinquency.23 26–31 A negative school environment also has demonstrated an association with adolescent substance use.32 33 Adolescent substance use typically follows a pattern in which licit drugs, such as tobacco and alcohol, precedes the use of cannabis and other illicit drugs.34 35

Aims of the study

The aim of the current study is to investigate the impact of parenting styles on adolescent substance use at a 32-month follow-up, after adjusting for potential risk factors for adolescent substance use: association with deviant peers, serving of alcohol by parents, parental substance use, delinquent behaviour and school environment as indicated by not liking school. The current study is based on data from a quasi-experimental study of evidence-based intervention programmes, and in the main study, it was found that the intervention had positive effects on adolescent substance use outcomes.36 While the effect of the interventions is not the focus of the present study, the experimental status into consideration to adjust for the effect of the intervention on substance use outcomes.

The main hypotheses are that parenting styles influence subsequent substance use behaviours in adolescents, and that authoritative parenting style will prove to be associated with less severe substance use outcomes. Secondary hypotheses are that other aspects of parental influence, as well as established predictors for adolescent substance use, such as delinquency, early onset of substance use, and association with deviant peers will be associated with subsequent substance use.

Subjects and methods

Study design

The present study is based on the first and the last waves of a longitudinal study on a sample of adolescents and their parents from 21 Swedish junior high schools in 2004–2007. The first data collection was in the autumn at grade 7, and thereafter, at the end of each semester. The study was based on a government-funded initiative aiming to evaluate effects of implementing evidence-based programmes for primary prevention of substance use. Eleven schools across Sweden participated as intervention schools, and 10 schools, matched by demographic variables, were selected as controls. The intervention schools received information about evidence-based prevention programmes, and were free to choose between any of the evidence-based programmes. Control schools received no special instructions about prevention programmes, and conducted ‘business as usual’ in this respect. The study is described in more detail elsewhere.36 37

Participants

A total of 2139 students (12–13 years old) started in the seventh grade in the 21 schools in 2004. A written consent for participation was received from 1436 (67%) parents. The 1436 participants who were eligible for participation were given questionnaires in the classroom at four waves during the junior high school. Data from the fall semester of seventh grade was used as baseline, and data from ninth grade, 32 months later, as follow-up. A total of 1268 adolescents completed the baseline questionnaire (48% girls), who constitute the sample of this study. Among included participants, 1080 answered the questionnaire in the ninth grade (47% girls).

Measurements

Parenting styles were assessed using two major aspects of parenting: responsiveness (the extent to which the child perceives his or her parents as warm, caring, loving, involved and responsive) and demandingness (parental monitoring, control and supervision).10 11 Participants answered 13 items on the parent–child relationship that were considered to fit the dimensions of the parenting style. Principal component analysis identified two factors that corresponded with the two dimensions proposed: responsiveness (6 items, α 0.78, eg, Do your parents let you participate when you make a decision in the family? Do you get to finish speaking when you discuss at home?) and demandingness (7 items, α 0.82, eg, If you go out on a Saturday night, do you have to tell your parents where you're going and who you're going to see?, Do you have to have your parents’ permission to stay out late in week nights?). The two scales were dichotomised using median split, and four categories of parenting styles were thus created: authoritarian (high demandingness/high responsiveness), authoritarian (high demandingness/low responsiveness), permissive (low demandingness/high responsiveness) and neglectful (low demandingness/low responsiveness). Since separate data on perceived parenting style were not available for different caregivers of each adolescent, all caregivers for each adolescent are collectively referred to as parents. In all analyses on parenting style, authoritative is the reference category.

Parental smoking and drinking were assessed with one multiple-choice item each: Who among your closest family and friends smoke daily or regularly? and Who among your closest family and friends drink alcohol regularly (at least once per week)? Any indication that one or both of the parents smoked or drank regularly was considered an affirmative answer. Parental provision of alcohol was assessed with the item: Does it happen that your parents serve you alcohol? The item How do you like it at school? was dichotomised, and the categories very badly, rather badly, neither well nor badly were compared with rather well and very well.

Association with deviant peers was assessed with eight questions regarding how many of the responder’s peers exhibit any of a list of deviant behaviours (eg, substance use, criminal behaviour, fighting and truancy). Answering categories were: none, maybe one or two, some, most and don’t know, and they were scored 0–3 (‘don’t know’ answers were excluded from the analyses). Principle component analysis indicated that all items load on a single factor and an index scale (α=0.83) with the range 0–24 points with an overall mean of 7.9 was created. Adolescent delinquency was assessed in a similar manner, with a scale consisting of 18 items (α=0.84) reflecting a range of delinquent behaviour including petty and major crimes against property as well as violent, sexual and drug-related crimes. Response categories were: never, 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–10 times and more than 10 times, and were given scores of 0–4. Scores for all items were summed. A majority (66.3%) answered never for all items and thus scored 0 points, and for this reason, a binary variable that separated participants who had committed any crime from all others was constructed.

Measures for adolescent substance use were constructed as dichotomous variables. Onset of alcohol drunkenness was assessed with the following item: have you ever drunk alcohol to the point of feeling drunk? Never was coded as no use, and once or more was coded as use. Drunkenness more than 10 times was coded from the same item, separating the highest category of more than 10 times from all others. Cigarette smoking was assessed with one item: Do you smoke? and any current regular use (sometimes or daily) was coded as regular smoking. Onset of illicit drug use was assessed with the items: Have you ever used illicit drugs? What kinds of illicit drugs have you tried; How many times have you used hashish or marijuana? and How many times have you used other illicit drugs than hashish or marijuana? Individuals who reported use of illicit drugs on any of these items were coded as having ever used illicit drugs.

The adolescent sex and type of school (intervention or control) were also included in the analyses, and the interaction terms between intervention group and parenting styles were also included in the initial stages of analysis.

Thirteen per cent of women and 10% of men reported having been drunk at baseline. In the first outcome measure, onset of drunkenness in junior high school, the focus was to study the onset of drinking alcohol to drunkenness during the course of junior high school, and those who had already been drunk at baseline were thus excluded from these particular analyses. Similarly, for the outcome measure onset of illicit drug use in junior high school that regards whether the adolescents had initiated illicit drug use during junior high school, those who had already used illicit drugs at baseline were excluded from these analyses. One per cent of the women and 0.6% of the men had ever used illicit drugs and were thus excluded from the analyses that used onset of illicit drug use during junior high school as the outcome.

Data analysis

Principal component analysis with oblique rotation was used for factor analysis of parenting style items. The principal model for multivariate analysis intended for this study was logistic regression. Three predictors could be included in different ways as described above: delinquency, deviant peers and not liking school. A variable selection process was first conducted by testing each of these variables against each baseline variable in bivariate regressions models. For delinquency, using the scalar variable as a linear predictor, as a non-linear predictor using regression splines, and the dichotomous item described above, were compared. For deviant peers, using the scalar variable as a linear predictor was compared to using it as a non-linear predictor using regression splines. For not liking school, the dichotomous item was compared to using the categories as indicator variables, and using the variable as a linear variable. When constructing models with regression splines, generalised additive models, were used instead of generalised linear models (GLMs), but retaining the binomial distribution assumption and logit link function. Models were compared using likelihood-ratio tests for nested models, and manual comparison of Akaike information criterion (AIC) for non-nested models. The variables with the best performance were the dichotomous items for delinquency and not liking school, and for deviant peers, the linear variable was preferred for the outcomes having been drunk more than 10 times and regular smoking, while the non-linear variable was preferred for the other two outcomes.

In the next stage, the full models were specified with all predictor variables, including interactions between parenting style and intervention group. The model selection process was based on likelihood-ratio tests and comparisons of AIC, and predictor variables that did not improve the models were dropped. All interaction terms were thus dropped, indicating that no interactions between parenting style and intervention group could be identified. In the first model, using lifetime drunkenness as the outcome, the deviant peers variable was dropped from the model, and the model was thus reduced to a GLM. Testing for multicollinearity proved a variance inflation factor below 1.15 for all variables included in the final analyses, indicating no underlying multicollinearity problem.38

Results

Descriptive characteristics

A majority (n=1268, 88.3%) answered the first questionnaire in the fall semester of the seventh grade. In table 1, the numbers of individuals eligible for analysis at each stage, as well as the final analysed samples, are shown. Descriptive baseline and follow-up data are shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Individuals eligible for analysis in each stage, by outcome

| Eligible at baseline | Follow-up data available | Included in the analyses* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of drunkenness | 1120 | 974 | 917 |

| Drunk more than 10 times | 1268 | 1080 | 986 |

| Regular smoking | 1268 | 1080 | 923 |

| Onset of illicit drug use | 1251 | 1068 | 984 |

*Numbers of complete cases (no missing data) used in the multivariate analyses.

Table 2.

Descriptive data at baseline and follow-up

| n | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline, 7th grade (n=1268) | ||

| Authoritative parenting style | 403 | 31.8 |

| Authoritarian parenting style | 201 | 15.9 |

| Permissive parenting style | 222 | 17.5 |

| Neglectful parenting style | 380 | 30.0 |

| Intervention school group | 504 | 39.7 |

| Female sex | 607 | 47.9 |

| Parental regular drinking | 527 | 41.6 |

| Parental daily smoking | 338 | 26.7 |

| Provision of alcohol by parents | 529 | 41.7 |

| Does not like it at school | 187 | 14.7 |

| Deviant peers (mean score) | 7.91 | |

| Delinquency | 423 | 33.4 |

| Lifetime drunkenness | 144 | 11.4 |

| Lifetime cigarette use | 320 | 25.2 |

| Regular smoking | 38 | 3.0 |

| Lifetime illicit drug use | 10 | 0.8 |

| Follow-up, 9th grade (n=1080) | ||

| Onset of drunkenness | 549 | 50.8 |

| Drunk >10 times | 199 | 18.4 |

| Regular smoking | 190 | 17.6 |

| Onset of illicit drug use | 54 | 5.0 |

Onset of drunkenness in junior high school

At follow-up in the ninth grade, 56% of females and 46.5% of males had been drunk at least once. In the bivariate analyses (table 3), permissive and neglectful parenting styles were associated with higher probability of having been drunk. Female sex, parental regular drinking, provision of alcohol by parents, deviant peers, delinquency and baseline cigarette use or regular smoking were also all associated with drunkenness. In the multivariate analysis (table 4), female sex, provision of alcohol by parents, delinquency and baseline cigarette use remained significantly associated with drunkenness.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations between parenting styles, other risk variables and adolescent substance use

| Onset of drunkenness |

Drunk >10 times |

Regular smoking |

Onset of illicit drug use |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=917) |

(n=968) |

(n=923) |

(n=986) |

|||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Authoritarian | 1.05 (0.70 to 1.56) | 0.84 | 0.51 (0.25 to 0.97) | 0.04 | 0.86 (0.45 to 1.59) | 0.66 | 0.76 (0.18 to 2.65) | 0.78 |

| Permissive | 1.68 (1.13 to 2.50) | 0.01 | 1.60 (0.98 to 2.59) | 0.05 | 1.65 (0.97 to 2.81) | 0.06 | 2.46 (0.99 to 6.28) | 0.04 |

| Neglectful | 1.97 (1.40 to 2.77) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.25 to 2.82) | <0.01 | 2.31 (1.50 to 3.60) | <0.001 | 2.25 (1.02 to 5.26) | 0.04 |

| Intervention school group | 1.13 (0.86 to 1.49) | 0.38 | 1.02 (0.73 to 1.44) | 0.93 | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.32) | 0.67 | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.07) | 0.07 |

| Female sex | 1.34 (1.02 to 1.76) | 0.03 | 1.64 (1.17 to 2.29) | <0.01 | 1.77 (1.23 to 2.53) | <0.01 | 1.07 (0.57 to 1.98) | 0.88 |

| Parental regular drinking | 1.41 (1.07 to 1.87) | 0.01 | 1.33 (0.95 to 1.86) | 0.10 | 1.24 (0.87 to 1.77) | 0.22 | 1.33 (0.71 to 2.46) | 0.37 |

| Parental daily smoking | 1.36 (0.99 to 1.88) | 0.06 | 1.45 (0.99 to 2.10) | 0.04 | 1.78 (1.21 to 2.60) | <0.01 | 1.72 (0.87 to 3.27) | 0.09 |

| Provision of alcohol by parents | 2.24 (1.69 to 2.97) | <0.001 | 2.17 (1.55 to 3.05) | <0.001 | 2.58 (1.81 to 3.69) | <0.001 | 1.38 (0.74 to 2.57) | 0.30 |

| Does not like it in school | 1.00 (0.66 to 1.50) | 1 | 1.07 (0.65 to 1.70) | 0.81 | 1.92 (1.19 to 3.03) | <0.01 | 2.11 (0.97 to 4.29) | 0.03 |

| Deviant peers | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.13) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.18) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.14 to 1.25) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.1 to 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Delinquency | 2.26 (1.67 to 3.07) | <0.001 | 3.09 (2.20 to 4.35) | <0.001 | 3.28 (2.29 to 4.71) | <0.001 | 3.67 (1.96 to 7.02) | <0.001 |

| Baseline drunkenness | 5.63 (3.50 to 9.08) | <0.001 | 7.89 (4.68 to 13.4) | <0.001 | 5.43 (2.62 to 10.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Baseline cigarette use | 4.81 (3.18 to 7.40) | <0.001 | 4.12 (2.88 to 5.90) | <0.001 | 6.32 (4.30 to 9.32) | <0.001 | 3.50 (1.86 to 6.53) | <0.001 |

| Baseline regular smoking | 8.27 (1.06 to 373.6) | 0.03 | 6.49 (2.63 to 16.6) | <0.001 | 27.5 (7.74 to 149.5) | <0.001 | 6.70 (1.83 to 20.4) | <0.01 |

| Baseline illicit drug use | Inf* | 0.47 | 6.48 (0.73 to 78.0) | 0.05 | 6.93 (0.79 to 83.8) | 0.04 | ||

*All of those who used illicit drugs at baseline had been drunk at follow-up, so no OR could be calculated

Table 4.

Multivariate associations between parenting styles, other risk variables, and adolescent substance use

| Onset of drunkenness |

Drunk >10 times |

Regular smoking |

Onset of illicit drug use |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=917) |

(n=968) |

(n=923) |

(n=986) |

|||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Authoritarian | 0.89 (0.59 to 1.33) | 0.56 | 0.37 (0.18 to 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.31 to 1.11) | 0.11 | 0.58 (0.18 to 1.88) | 0.36 |

| Permissive | 1.37 (0.92 to 2.06) | 0.12 | 1.06 (0.64 to 1.74) | 0.83 | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.74) | 0.98 | 1.56 (0.66 to 3.73) | 0.31 |

| Neglectful intervention school group | 1.38 (0.97 to 1.97) | 0.07 | 0.94 (0.6 to 1.47) | 0.79 | 0.99 (0.60 to 1.61) | 0.96 | 1.08 (0.48 to 2.43) | 0.86 |

| 0.57 (0.31 to 1.03) | 0.06 | |||||||

| Female sex parental regular drinking | 1.41 (1.07 to 1.86) | 0.02 | 1.74 (1.23 to 2.76) | <0.01 | 1.86 (1.26 to 2.73) | <0.01 | ||

| Parental daily smoking | 1.19 (0.77 to 1.81) | 0.42 | ||||||

| Provision of alcohol by parents | 1.79 (1.34 to 2.39) | <0.001 | 1.41 (0.98 to 2.02) | 0.06 | 1.58 (1.07 to 2.34) | 0.02 | ||

| Does not like it in school | ||||||||

| Deviant peers | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.1) | 0.11 | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.16) | <0.001 | * | 0.03 | ||

| Delinquency | 1.58 (1.14 to 2.18) | <0.01 | 1.87 (1.28 to 2.73) | <0.01 | 1.72 (1.14 to 2.58) | <0.01 | 2.23 (1.16 to 4.29) | 0.02 |

| Baseline drunkenness | 2.19 (1.29 to 3.72) | <0.01 | 2.31 (1.29 to 4.14) | <0.01 | 2.56 (1.21 to 5.41) | 0.01 | ||

| Baseline cigarette use, baseline regular smoking | 3.69 (2.45 to 5.66) | <0.001 | 2.31 (1.53 to 3.47) | <0.001 | 3.37 (2.18 to 5.2) | <0.001 | ||

| Baseline illicit drug use | ||||||||

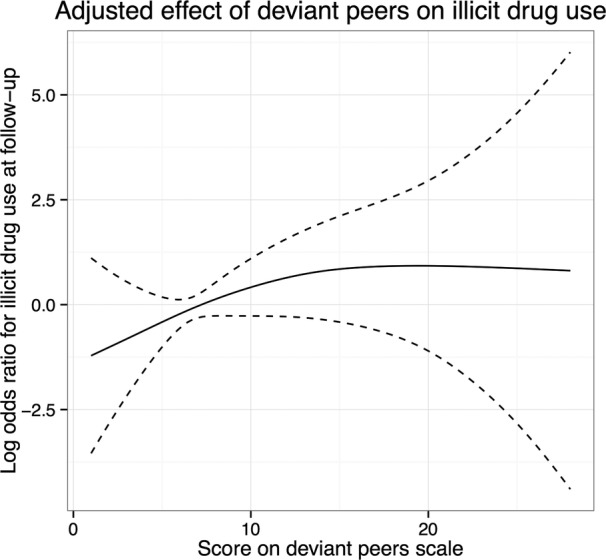

*See diagram in figure 2.

Drunkenness more than 10 times at follow-up

In the follow-up assessment, 22.3% of the women and 15% of the men reported having been drunk more than 10 times. Authoritarian parenting, compared to authoritative parenting, was associated with 49% lower odds (p=0.036) of the adolescent having been drunk more than 10 times (table 3). Permissive and neglectful parenting styles were associated with 60% and 87% higher odds, respectively (p=0.053 and 0.002). Most other predictor variables were also associated with a higher probability of having been drunk more than 10 times. Table 4 shows that authoritarian parenting remained significantly associated with lower odds of being drunk more than 10 times after adjusting for other predictor variables. Female sex, delinquency and baseline drunkenness or cigarette use remained significantly associated with drunkenness more than 10 times.

Regular smoking at follow-up

A total of 23.6% of the women and 13.5% of the men reported regular smoking at follow-up. As can be seen in table 3, neglectful parenting was associated with 131% higher odds of regular smoking at follow-up in the bivariate analysis (p<0.001). With the exceptions of the experimental group and parental drinking, all other predictor variables were associated with regular smoking at follow-up. After adjusting for confounding variables (table 4), none of the parenting styles remained associated with regular smoking. Female sex, provision of alcohol by parents, deviant peers, delinquency and baseline drunkenness or cigarette use remained statistically significantly associated with regular smoking at follow-up.

Onset of illicit drug use during junior high school

In the ninth grade, 5.2% of women and 4.8% of the men reported having used illicit drugs. In the bivariate analyses (table 3), permissive and neglectful parenting were associated with higher odds of having used illicit drugs at follow-up. Adolescents who did not like it in school, had deviant peers, exhibited delinquent behaviour, or had been drunk or used cigarettes at baseline, also had a higher probability of having used illicit drugs at follow-up. In the multivariate analysis (table 4), parenting style did not remain significantly associated with illicit drug use at follow-up, but deviant peers, delinquency and having been drunk at baseline remained significantly associated with illicit drug use. Figure 1 demonstrates the non-linear relationship between the deviant peers scale and illicit drug use, where the log OR seems to reach a plateau of about 0.8 at a scale value of 15, indicating that the odds of illicit drug use are increased by approximately 120% (p=0.026).

Figure 1.

Non-linear association between the deviant peers scale and illicit drug use at follow-up. Values on the y-axis denote log odds ratio (solid line) and 95% confidence intervals (dotted lines).

Post hoc analyses

To assess generalisability of our results, four sets of post hoc analyses were conducted. First, the intervention group was compared with the control group on all baseline variables to assess whether the groups were equivalent. The only significant difference between the groups was that adolescents in the intervention groups had a lower mean on the deviant peers scale (7.72 vs 8.20, p=0.015). The second set of analyses aimed to assess whether the final analysed samples differed from those eligible for analysis for each outcome. Smoking at baseline and having smoking parents were significantly associated with being excluded from analysis across all outcomes. For all outcomes but onset of drunkenness, there were also other statistically significant associations in expected directions, so that those who reported delinquency, deviant peers, other substance use, etc, had a lower chance of being included in the final analyses. Logistic regression models applied to each group demonstrated that the most consistently significant variable associated with being excluded was cigarette use at baseline, followed by baseline drunkenness and parental daily smoking. The third set of analyses was a sensitivity analysis to determine the influence of the dropouts from follow-up assessment. First, dropouts were coded as positive on each outcome measure, and the same regression models were applied. Second, they were coded as negative on each outcome measure, and the regression models were applied again. The differences in estimated coefficients and p values were minimal compared to the analyses presented in table 4. The only difference regarding parenting styles was that, when assuming that dropouts had been drunk more than 10 times, authoritarian parenting style was no longer significantly negatively associated with that outcome (p=0.180). Post-stratification weighting was conducted and all the regression models were run again using weighted data.39 The census data used for weighting were country of birth, parents’ country of birth, whether the adolescent lived with their both biological parents or not. Those data were gathered from Statistics Sweden.40 The results were highly similar to the results reported in table 4 with respect to ORs, CIs and statistical significance. The only exception was that, in the post hoc analysis of weighted data, authoritarian parenting style was negatively associated with regular smoking at follow-up (OR 0.45, 0.23to 0.91, p=0.026).

Discussion

With the exception of having been drunk more than 10 times, parenting style does not seem to influence the substance use outcomes when other risk factors are taken into consideration.

The strongest predictors for having been drunk at least once at follow-up were female sex, parents’ serving of alcohol, delinquency and having used cigarettes at baseline. Permissive and neglectful parenting styles were strongly associated with higher rates of onset of drunkenness in the bivariate analyses, but when controlling for important risk factors for adolescent substance use these associations did not reach statistical significance. The association between provision of alcohol by parents and increased drinking behaviour has been consistent in the literature6 7 9 and is further confirmed in the present study. Delinquency and cigarette use at baseline also predicted having been drunk at follow-up, confirming results from previous studies.28 35

The results for drunkenness more than 10 times at follow-up were slightly different. While delinquency and cigarette use were important for this outcome, authoritarian parenting was associated with slightly lower odds of having been drunk more than 10 times than authoritative parenting. Having deviant peers was found to be associated with a higher risk of having been drunk 10 times. Being served alcohol at home was not associated with having been drunk more than 10 times and perceived parental patterns of alcohol and cigarette use did not affect any of the alcohol use outcomes in the multivariate analyses. A question that arises is why authoritarian parenting seems to have a protective effect on more frequent alcohol consumption when this association cannot be seen in the other studies.13 14 17 One possible explanation might be that parenting styles often are operationalised slightly differently, and some studies employ tertiary split instead of median split.12 17 Also, the results may reflect cultural differences in the associations between parenting styles and alcohol use, as other studies have shown that the importance of parental control can vary across cultures.20 21 This might also apply to the associations between parenting styles and adolescent regular smoking, as indicated by the post hoc analyses in which authoritarian parenting style was significantly associated with lower odds of adolescent regular smoking at follow-up.

Neglectful parenting was associated with a higher risk of regular smoking at follow-up. However, when adjusting for potentially confounding variables, this association disappeared. In the multivariate analysis, serving of alcohol by parents was associated with regular smoking at follow-up. While data on smoking-specific rules is unavailable, it might be hypothesised that serving of alcohol by parents is associated with a more lax attitude to substance use in general. The results of the present study indicate that early onset of substance use, deviant peers, delinquency, and early onset of cigarette or alcohol use are more important than parenting style for regular smoking. This is in agreement with some previous studies,13 14 although in conflict with others.16 In the current study, before adjusting for confounders, neglectful parenting was indeed associated with smoking, but this association disappeared when controlling for other risk factors. The present study takes more confounding variables into account than previous studies. This might indicate that the differences in regular smoking noted in the study by Chassin and colleagues20 21 may be explained by other factors rather than parenting styles. It could be that parenting style is of importance as a marker, but not as a potential modulator of risk.

Permissive and neglectful parenting styles were clearly associated with onset of illicit drugs at follow-up. However, when adjusting for drunkenness at baseline, delinquency and association with deviant peers, these associations disappeared. These results point in the same direction as what Shakya et al14 reported, but partly contradict the findings of Adalbjarnardottir and colleagues,13 in which authoritative parenting was identified as being protective against cannabis and amphetamine use. The divergent results might be due to the more comprehensive set of confounding variables taken into account in the present study, including variables, such as deviant peers and delinquency, which appear to be more important than parenting style for illicit drug use.

Strengths and limitations

The present study is the second largest longitudinal study on the impact of parenting styles, as conceptualised by Maccoby and Martin,11 on adolescent substance use. A major strength is the inclusion of several known risk factors for adolescent engagement in substance use, and the rate of adolescent participation in the study might be considered high in a school setting.

A major limitation is the lack of a generally acknowledged method of operationalising parenting styles,12 potentially limiting the possibility of comparing results. However, the method used in the present study is very similar to the one used in previous studies.12 Another limitation is that only 73–82% of eligible individuals at baseline could be included in the analyses. An attrition analysis indicated that baseline substance use as well as deviant peers, delinquency, parental drinking and smoking were more common in excluded subjects. Thus, our final sample may represent a group with less problem behaviours and risk factors than the average, and that our results may not be generalisable to groups with higher risk of problem behaviours. However, in the sensitivity analysis, assuming that dropouts were either positive or negative for all outcomes had minimal impact on the outcomes. In the post hoc analyses on census-weighted data, the results remained largely unchanged with the exception of the influence of authoritarian parenting style on regular smoking. The association was seen also in the main analysis (table 4), though not significant at the 0.05 level. This means that the results of the present study seem reasonably representative of this age group. The results also indicate that there might be different effects of authoritarian parenting style on adolescent regular smoking in different groups of adolescents. However, testing this hypothesis is outside the scope of the present study.

The current study is based entirely on children’s report of parenting style and other parental behaviours. However, previous research indicates that parenting styles as perceived by adolescents may be more accurate in predicting outcomes than if perceived by parents.16 The lack of parental report of own substance use and rules on adolescent substance use outside of home constitutes another limitation, since previous studies have indicated that these factors are important for substance use outcomes in adolescents.9 Finally, while the prevalence of illicit drug use in the present study is comparable with the results of the Swedish annual national survey of students’ drug habits (5.6% for students in the 9th grade in 2007), the low prevalence of illicit drug use in this setting might make it difficult to generalise the results to high-prevalence settings.

Conclusions

When other factors were taken into account, parenting styles, as operationalised in the present study, were found to be of little or no importance for the onset of substance use among adolescents. Specific rules concerning substance use, substance use among peers, and early delinquency and substance use seem to be more important for the development of substance use behaviours among adolescents. Our results indicate that, perhaps, preventive efforts should be focused on these areas rather than at the quality of the relationship between parent and child.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB has had the main responsibility for calculating statistics and writing the paper. KS is the principal investigator for the project, has had a counselling function in planning the present paper, and has actively taken part in revising the paper. AÖ and AH have taken part in planning and writing the paper, as well as revisions of the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and from the Department of Welfare and Education, City of Stockholm Executive Office.

Competing interests: JB reports grants from Lindhaga Foundation, a non-profit foundation that supports research in psychiatry, and grants from Skåne University Hospital to support his work as a PhD student, during the conduct of the study. AH reports grants from Skåne University Hospital, during the conduct of the study; grants from Svenska spel (Swedish governmental gambling monopoly, publicly owned), personal fees from Lundbeck, non-financial support from Hovenia Dulcis AB, non-financial support from A Carlsson Research AB, outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E et al. . Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. J Stud Alcohol 1997;58:280–90. 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse 1998;10:163–73. 10.1016/S0899-3289(99)80131-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewit DJ, Hance J Offord DR et al. . The influence of early and frequent use of marijuana on the risk of desistance and of progression to marijuana-related harm. Prev Med 2000;31:455–64. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ et al. . Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Prev Med 2004;39:976–84. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hibell B, Guttormsson U, AhlströM S et al. . 2011 ESPAD report: Substance use among students in 36 European countries, E.M.C.f.D.a. Addiction, Editor Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mcmorris BJ, Catalano RF, Kim MJ et al. . Influence of family factors and supervised alcohol use on adolescent alcohol use and harms: similarities between youth in different alcohol policy contexts. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2011;72:418–28. 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foley KL, Altman D, Durant RH et al. . Adults’ approval and adolescents’ alcohol use. J Adolesc Health 2004;35:345.e17–26. 10.1016/S1054-139X(04)00053-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull 1992;112:64–105. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:774–83. 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet Psychol Monogr 1967;75:43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maccoby E, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In: Mussen PH, ed Handbook of child psychology.. New York: Wiley, 1983:1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becoña E, Martínez Ú, Calafat A et al. . Parental styles and drug use: a review. Drugs 2015;19:1–10. 10.3109/09687637.2011.631060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adalbjarnardottir S, Hafsteinsson LG. Adolescents’ perceived parenting styles and their substance use: concurrent and longitudinal analyses. J Res Adolesc 2001;11:401–23. 10.1111/1532-7795.00018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shakya HB, Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Parental influence on substance use in adolescent social networks. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:1132–9. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Čablová L, Pazderková K, Miovský M. Parenting styles and alcohol use among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Drugs 2015;21:1–13. 10.3109/09687637.2013.817536 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose J et al. . Parenting style and smoking-specific parenting practices as predictors of adolescent smoking onset. J Pediatr Psychol 2005;30:333–44. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shucksmith J, Glendinning A, Hendry L. Adolescent drinking behaviour and the role of family life: a Scottish perspective. J Adolesc 1997;20:85–101. 10.1006/jado.1996.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolkan C, Sano Y, De Costa J et al. . Early adolescents’ perceptions of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and problem behavior. Marriage Fam Rev 2010;46:563–79. 10.1080/01494929.2010.543040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen DA, Rice J. Parenting styles, adolescent substance use, and academic achievement. J Drug Educ 1997;27:199–211. 10.2190/QPQQ-6Q1G-UF7D-5UTJ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia F, Gracia E. Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolescence 2009;44:101–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason CA, Walker-Barnes CJ, Tu S et al. . Ethnic differences in the affective meaning of parental control behaviors. J Prim Prev 2004;25:59–79. 10.1023/B:JOPP.0000039939.83804.37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marschall-Levesque S, Castellanos-Ryan N, Vitaro F et al. . Moderators of the association between peer and target adolescent substance use. Addict Behav 2014;39:48–70. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnow S, Schultz G, Lucht M et al. . Do alcohol expectancies and peer delinquency/substance use mediate the relationship between impulsivity and drinking behaviour in adolescence? Alcohol Alcohol 2004;39:213–19. 10.1093/alcalc/agh048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monahan KC, Rhew IC, Hawkins JD et al. . Adolescent Pathways to Co-Occurring Problem Behavior: the effects of peer delinquency and peer substance use. J Res Adolesc 2014;24:630–45. 10.1111/jora.12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen M, Donohue WA, Griffin A et al. . Comparing the influence of parents and peers on the choice to use drugs: a meta-analytic summary of the literature. Crim Justice Behav 2003;30:163–86. 10.1177/0093854802251002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer RH, Knopik VS, Rhee SH et al. . Prospective effects of adolescent indicators of behavioral disinhibition on DSM-IV alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug dependence in young adulthood. Addict Behav 2013;38:2415–21. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Windle M, Windle RC. Early onset problem behaviors and alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use disorders in young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;121:152–8. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burdzovic Andreas J, Jackson KM. Adolescent alcohol use before and after the high school transition. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015;39:1034–41. 10.1111/acer.12730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiramura H, Uji M, Shikai N et al. . Understanding externalizing behavior from children's personality and parenting characteristics. Psychiatry Res 2010;175:142–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma L, Markon KE, Clark LA. Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: a meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures. Psychol Bull 2014;140:374–408. 10.1037/a0034418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong JM, Ruttle PL, Burk LR et al. . Early risk factors for alcohol use across high school and its covariation with deviant friends. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2013;74:746–56. 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonell C, Parry W, Wells H et al. . The effects of the school environment on student health: a systematic review of multi-level studies. Health Place 2013;21:180–91. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazzeri G, Azzolini E, Pammolli A et al. . Factors associated with unhealthy behaviours and health outcomes: a cross-sectional study among Tuscan adolescents (Italy). Int J Equity Health 2014;13:83 10.1186/s12939-014-0083-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Chiu WT et al. . Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;108:84–97. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E et al. . Is cigarette smoking a gateway to alcohol and illicit drug use disorders? A study of youths with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2006;59:258–64. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrer-Wreder L, Sundell K, Eichas K et al. . An empirical test of a diffusion framework for school-based prevention: the 21 Swedish junior high school study. J Community Psychol 2015;43:811–31. 10.1002/jcop.21709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plenty S, Sundell K. Graffiti: a precursor to future deviant behaviour during adolescence. Deviant Behav 2015;36:565–80. 10.1080/01639625.2014.951569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Djurfeldt B. Statistisk verktygslåda 2—multivariat analys. 2009:113–14. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little R. Post-stratification: a modeler's perspective. J Am Stat Assoc 1993;88:1001–12. 10.1080/01621459.1993.10476368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Statistics Sweden. [Hemmaboende barn och ungdomar 0–21 år som bor med biologiska föräldrar och styvförälder efter kön, ålder, familjetyp (sammanboende eller ensamstående föräldrar) och utländsk/svensk bakgrund. År 2000–2014]. Statistics Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]