Abstract

A lipoma is one of the most common benign tumours and can develop at any location in the body. Lipomas present characteristic imaging features; hence, they are easy to identify on CT and MRI. However, cases of necrotic lipoma are rarely encountered; therefore, information on the imaging findings of necrotic lipomas is scarce. In the present report, we describe the case of a 63-year-old man with necrotic lipoma in the deep layer of the posterior thigh, which resembled a liposarcoma on imaging. To the best of our knowledge, only a few reports on necrotic lipoma on the extremities have been published.

Background

Lipomas are the most common benign tumours of mesenchymal origin, and can develop at any location on the body;1 however, only a few reports of lipoma with necrosis have been published so far. Lipomas present certain characteristic findings on CT and MRI.2 However, only a few reports have described both radiographic and histological findings in cases of lipoma with necrosis.3 4 In the present report, we describe a case of a man with a necrotic lipoma located at the posterior thigh that was preoperatively misdiagnosed as a liposarcoma on MRI.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old man was referred to our hospital, with a 10-year history of a slowly enlarging painless mass at the posterior thigh. Physical examination indicated a soft, non-painful mass, approximately 6 cm in size, in the deep posterior thigh. He had a history of lung cancer and kidney cancer, and had undergone chemotherapy, including anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor therapy.

Investigations

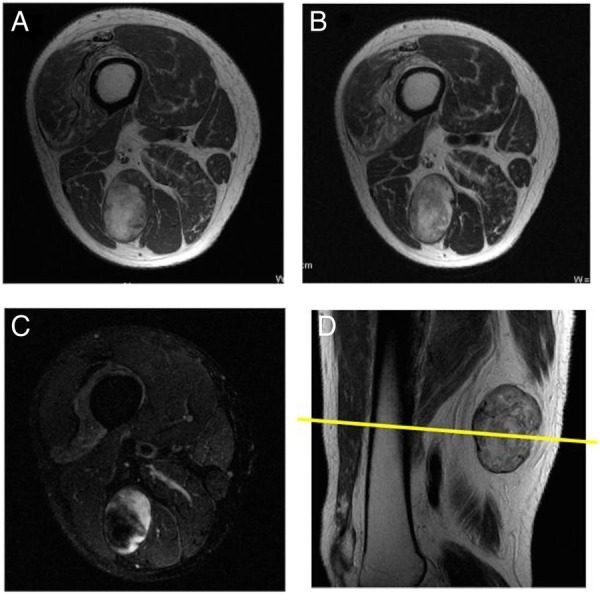

MRI indicated a round soft-tissue mass lesion, measuring 4×6 cm, located in the deep portion of the posterior thigh, between the biceps femoralis and semimembranosus muscle (figure 1). The majority of the mass lesion showed high-intensity signals on T1-weighted (figure 1A) and T2-weighted (figure 1B, D) imaging, which reduced after the fat-suppression technique was adopted (figure 1C), indicating an adipose component in the mass. Moreover, a tumour was also suspected in the lesion, as it showed iso-intense signals on T1-weighted imaging (figure 1A), high-intensity signals on T2-weighted imaging (figure 1B) and irregularly shaped mild contrast enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration (figure 1C), which suggested no lipomatous component.

Figure 1.

(A) T1-weighted, (B) T2-weighted fat suppression, (C) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat suppression preoperative axial view, (D) T1-weighted sagittal view of MRI shows a well-demarcated round lipomatous lesion in the posterior thigh with a non-lipomatous component at the periphery of the tumour. The non-lipomatous component shows good enhancement on gadolinium administration.

Differential diagnosis

Myxoid liposarcoma

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma

Encapsulated fat necrosis

Acute pancreatitis

Membranous fat necrosis.

Treatment

A percutaneous biopsy of the lesion was performed, and specimens were found to comprise fat and fibrous tissue, which was not suggestive of a malignant tumour. Based on the MRI findings, we inferred that the lesion was a myxoid liposarcoma or dedifferentiated liposarcoma, and hence performed incisional biopsy; however, no atypical cells, but only necrotic fat and fibrous tissue, were observed, similar to the findings of the percutaneous biopsy. Therefore, the patient was scheduled for tumour resection. As the tumour was attached to the surrounding muscles, the tumour along with a part of the surrounding muscles was resected. Pathological examination indicated that the tumour was composed of necrotic fat tissue with no cytological atypia, and surrounded by a fibrous capsule (figure 2A, B). The features were consistent with necrotic lipoma. The deep portion of the tumour, corresponding with the well-enhanced area on MRI, showed highly degenerative changes and focal fibrosis with neovascularisation (figure 2C), which was highlighted on CD34 immunohistochemistry (figure 2D).

Figure 2.

(A) Macroscopic picture demonstrating a well-defined yellow mass, which is consistent with necrotic lipoma. (B) On histological examination, the tumour was composed of necrotic adipose tissues. Note the highly degenerative area with focal fibrosis on the left side, which is enhanced on MRI. (C) On higher magnification (square area in B), the adipose tissue in the total necrosis area shows focal cystic degeneration and fibrosis. (D) CD34 immunostaining indicates the vascular channels in the fibrous area.

Outcome and follow-up

A follow-up examination after 6 months did not show any evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

We describe a case of a man with a necrotic lipoma located on the deep layer of the posterior thigh that mimicked a liposarcoma.

Only a few reports on necrotic lipoma have been published.3–5 Fat necrosis is observed in rare conditions such as encapsulated fat necrosis,6 pancreatic fat necrosis7 and membranous fat necrosis.8 Encapsulated fat necrosis presents as a distinct subcutaneous lesion, and is characterised by nodular cystic fat necrosis encapsulated by fibrous tissue that is mobile in the subcutis. The pathogenesis of encapsulated fat necrosis is thought to involve trauma and steroid treatment, and subsequent blood supply loss. Moreover, pancreatic fat necrosis is observed in cases of acute pancreatitis and presents as an inflammatory lesion. On the other hand, membranous fat necrosis is characterised by the development of pseudocystic cavities lined by hyaline-crenulated membranes. It may be caused by multiple local or systemic events, which lead to the disturbance of blood supply in the subcutaneous tissue. These conditions are usually noted in the subcutis;6 however, the tumour in the present case was located in the deep layer, and its pathogenesis was suspected to differ from the pathogenesis of these conditions.

We inferred that the necrotic lipoma observed in the present case was related to the interruption of blood supply due to a specific cause. Our patient had previously undergone chemotherapy for lung and kidney cancer, and had also received steroid and anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor therapy, which could have led to the disturbance of blood supply and the development of necrotic lipoma.

The MRI features of patients with lipomatous masses are usually sufficiently characteristic to enable an accurate diagnosis.2 However, information regarding the imaging findings of necrotic lipoma is scarce. Lipoma is characterised by the appearance of homogeneous fatty attenuation on CT and homogeneous signal intensity identical to that of fat in all pulse sequences on MRI.2 In contrast, on MRI, myxoid liposarcoma appears as a well-defined mass with low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and marked high-signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, in relation to the adjacent muscle, which suggests a myxoid component.9 Moreover, on T1-weighted and T2-weighted imaging, the tumour component shows linear or nodular areas of high-signal intensity that disappear after fat saturation, which corresponds to the lipomatous component of the lesion. In myxoid liposarcoma, the proportion of the lipomatous area reportedly accounts for only a small volume of the overall mass size (<10% of the lesion).10 In the present case, the proportion of the lipomatous area in the lesion was high, which was not consistent with the features of myxoid liposarcoma. Furthermore, dedifferentiated liposarcoma shares radiological features with a well-differentiated liposarcoma associated with non-lipomatous lesions.10 This latter lesion has a typically non-specific nodular appearance, and frequently contains areas of haemorrhage and necrosis. In the present case, the tumour contained non-lipomatous lesions with good enhancement on gadolinium administration, which potentially indicated the presence of a malignant component. Chan et al4 reported the imaging features of two cases of necrotic lipoma, where the necrotic area appeared as an amorphous cloud-like stranding and serpentine-like feature rather than a nodular pattern; however, the authors reported that the imaging findings of necrotic lipoma can be distinguished from liposarcoma. The enhanced lesion on MRI in the present case did not contain atypical cells, and we suspect that the lesion was related to the revascularisation of fibrous tissue after fat necrosis.

In conclusion, we describe the MRI findings of a case of necrotic lipoma. Necrotic lipoma is a rare condition, and resembles other lipomatous tumours, particularly myxoid liposarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Hence, necrotic lipoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of lipomatous tumours.

Learning points.

Necrotic lipoma is a rare condition, and should be included in the differential diagnosis of lipomatous tumours.

The MRI features of necrotic lipoma resemble those of other lipomatous tumours, particularly myxoid liposarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

Necrotic lipoma can contain non-lipomatous lesions with good enhancement by gadolinium on MRI.

Footnotes

Contributors: TO wrote the manuscript. TU was the histopathologist. YS reviewed the literature and HK corrected the draft.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Unnni KK, Mertens F. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press, 2014:20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kransdorf MJ, Bancroft LW, Peterson JJ et al. Imaging of fatty tumors: distinction of lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma. Radiology 2002;224:99–104. 10.1148/radiol.2241011113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreu C, Yat-Wah P, Fraga J et al. Necrotic lipoma of the posterior mediastinum. Arch Bronconeumol 2008;44:641–4. 10.1157/13128331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan LP, Gee R, Keogh C et al. Imaging features of fat necrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:955–9. 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1810955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López Soriano A, Tomasello A, Luburich P et al. Fat necrosis in a chest wall lipoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:866 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azad SM, Cherian A, Raine C et al. Encapsulated fat necrosis: a case of ‘thigh mouse’. Br J Plast Surg 2001;54:643–5. 10.1054/bjps.2001.3657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. Evidence that lipase and amylase alone do not induce lipocyte necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:359–64. 10.1016/S0190-9622(87)70213-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snow JL, Su WP. Lipomembranous (membranocystic) fat necrosis. Clinicopathologic correlation of 38 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 1996;18:151–5. 10.1097/00000372-199604000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung MS, Kang HS, Suh JS et al. Myxoid liposarcoma: appearance at MR imaging with histologic correlation. Radiographics 2000;20:1007–19. 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl021007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Ouni F, Jemni H, Trabelsi A et al. Liposarcoma of the extremities: MR imaging features and their correlation with pathologic data. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96:876–83. 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]