Abstract

Gastrointestinal (GI) angiodysplasia is an important and challenging cause of acute GI haemorrhage, particularly in the elderly. We present the case of an 83-year-old woman admitted with acute upper GI bleeding that was refractory to both endoscopic ablation with argon plasma coagulation and gastroduodenal artery embolisation. Administration of thalidomide 100 mg daily after failure of the above therapeutic procedures resulted in cessation of bleeding and avoided the need for further blood transfusion at 6-month follow-up.

Background

Angiodysplasia (AD) is the most common vascular malformation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in adults as well as being an important cause of both occult and overt bleeding in these patients.1 AD is defined as pathologically dilated communications between veins and capillaries within the mucosa and submucosa. These ectatic, tortuous and thin-walled veins, venules and capillaries become prone to bleeding.2 AD can occur throughout the GI tract and more than half of patients will have multiple lesions.3 Although rare, AD is estimated to be responsible for 4–7% of non-variceal upper GI bleeds.1

The pathogenesis of AD is not fully understood, but an increased expression of pro-angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), may play an important role in aberrant angiogenesis within the submucosa, leading to the formation of ADs.4 The use of antiangiogenic therapy, such as thalidomide, has therefore surfaced in an increasing body of evidence as a potential treatment for bleeding AD.

Up to 50% of GI ADs stop bleeding without requiring any intervention.5 Endoscopy is the mainstay diagnostic and treatment modality for bleeding AD, particularly involving therapy with argon plasma coagulation (APC). Enteroscopic techniques may also be performed at endoscopy, such as push enteroscopy and deep small bowel enteroscopy (eg, double-balloon enteroscopy).1 Wireless capsule enteroscopy is the preferred first-line investigation endorsed by the British Society of Gastroenterology, for suspected obscure GI bleeding, where the source of haemorrhage is not identified on upper or lower GI endoscopy.6

Despite endoscopic therapy, up to 25% of patients have recurrent overt bleeding.5 In cases of acute severe bleeding or treatment-resistant bleeding, interventional radiology or surgical resection may provide the only treatment option. Systemic pharmacological therapies, such as thalidomide, offer an alternative option in a number of settings. Endoscopic treatment may be ineffective, particularly if there are multiple lesions in an indeterminate location, particularly the small bowel.1 They may also be offered to patients who are at high risk of complications from, or who do not wish to embark on, invasive treatment. Other systemic therapies found within the literature include hormonal therapy (combined oestrogen and progesterone) and somatostatin analogues.5

Case presentation

We present a case of an 83-year-old woman admitted via the acute Medical intake with haematemesis and melaena. She had a medical history of hypertension and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with interferon α. She had no family history to note, was a non-smoker, drank very little alcohol and lived alone independently. Other than age, she had no specific risk factors for AD, most notably history neither of aortic stenosis, nor von Willebrand disease nor of chronic renal failure.1

Investigations

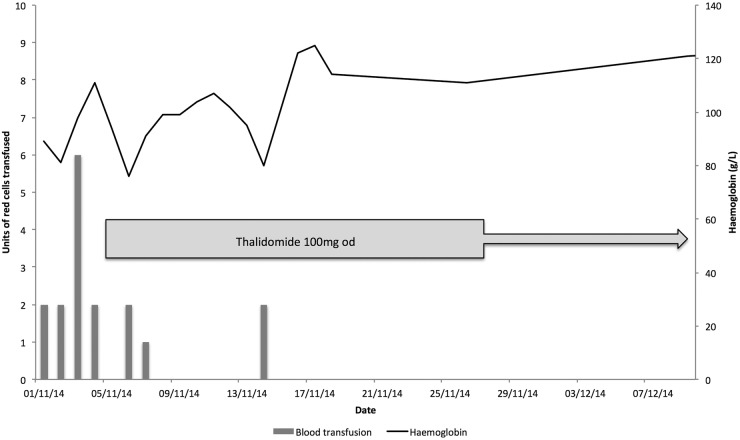

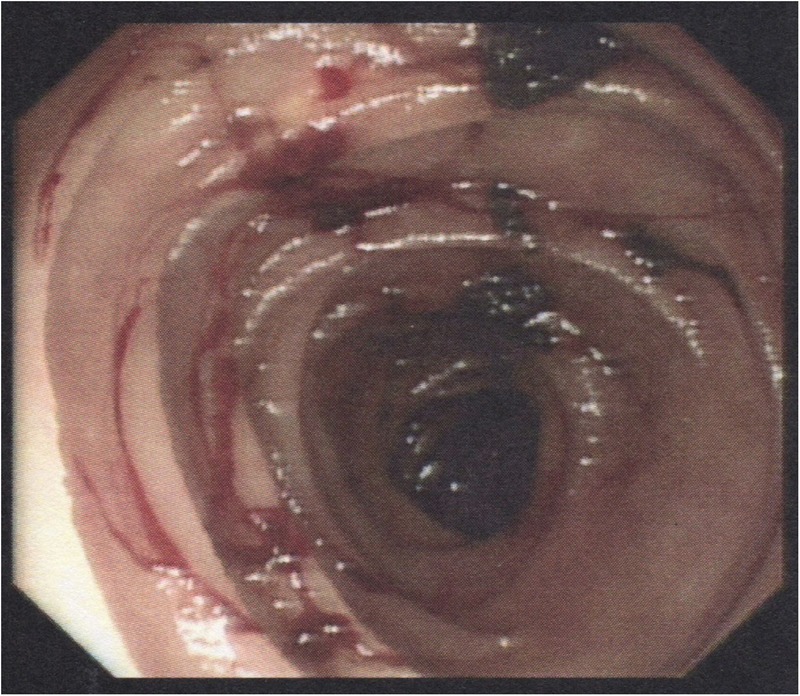

The patient was actively bleeding on admission to hospital, with a presenting haemoglobin count of 89 g/L and urea of 17.7 mmol/L. Platelet count was normal and she had no coagulopathy. Upper GI endoscopy was performed on the day of admission, initially with a gastroscope and then with a paediatric colonoscope, as she was found to have AD with multiple sources of bleeding in the stomach and duodenum. The paediatric colonoscopy was used to examine the upper 60 cm of jejunum. Multiple AD lesions were visualised to be actively bleeding, mainly in the duodenum and jejunum (figures 1 and 2). As many lesions as possible were ablated with APC but it was felt there were surely many more lesions beyond the reach of the paediatric colonoscopy not amenable to endoscopic therapy.

Figure 1.

Actively bleeding duodenal and small bowel angiodysplasia visualised at endoscopy.

Figure 2.

Actively bleeding duodenal and small bowel angiodysplasia visualised at endoscopy.

Treatment

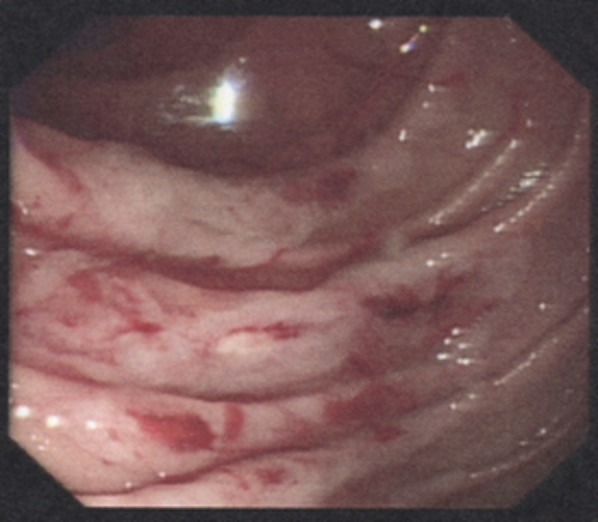

The patient subsequently continued to have active upper GI bleeding despite endoscopic therapy and intravenous tranexamic acid 1 g three times daily. On the third day of admission, gastroduodenal artery embolisation was performed radiologically via the common femoral artery. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have ongoing bleeding, and during the first 4 days of admission required 12 units of blood in order to maintain her haemoglobin at satisfactory levels (figure 3). On the fifth day of admission, thalidomide 100 mg daily was started.

Figure 3.

Graph illustrating red cell transfusion requirements and haemoglobin concentration plotted against time of administration of thalidomide.

Outcome and follow-up

Over the following week the patient's bleeding settled and urea returned to normal. She required 3 units of blood on days 2 and 3 after starting thalidomide, with a further transfusion of 2 units on day 10. Following an 18-day hospital admission, she was discharged home on thalidomide 100 mg daily. The patient has, for the past 6 months, had no further GI bleeding and her haemoglobin has remained above 120 g/L without any blood transfusions.

She did, however, develop central nervous system side effects after starting thalidomide, including dizziness and unsteadiness. She was assessed by a stroke physician, who identified a right lower limb ataxic hemiplegic gait with truncal ataxia and peripheral neuropathy. A brain MRI was performed, which was consistent with background small vessel cerebrovascular disease and posterior circulation atherosclerosis. Although thalidomide was likely contributing to her peripheral neuropathy and ataxia, the patient was keen to continue with treatment and manage with her neurological symptoms.

Discussion

We report a case of acute GI AD haemorrhage successfully treated with thalidomide. This case highlights a role for systemic therapy in treating multiple bleeding AD lesions that are refractory to endoscopic ablation or radiological artery embolisation.

There is currently limited high-grade evidence for the use of thalidomide in treating AD available in the literature. One randomised controlled trial (RCT) compared thalidomide 100 mg daily to oral iron in 55 patients refractory to treatment.7 In this study, the response rate was 71% in the treatment group compared to 4% in the control group (treatment response defined as at least a 50% reduction in bleeding episodes at 1 year). Bleeding stopped in 46% receiving thalidomide, compared to 0% in the control group.

Similar to the case we present in this article, the RCT also demonstrated significant adverse effects, particularly central nervous system side effects, associated with thalidomide use; 71% of patients reported adverse events in the thalidomide group, particularly fatigue (32%), constipation (25%), dizziness (21%) and peripheral oedema (14%). However, it is worth noting that these side effects are not necessarily a barrier to ongoing treatment, as highlighted in this case report.

Learning points.

Thalidomide can provide effective treatment for patients with acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding secondary to angiodysplasia (AD) lesions that are refractory to conventional endoscopic therapy and/or interventional radiology.

Patients and clinicians should, however, be wary of adverse effects, particularly central nervous system side effects, associated with the administration of thalidomide.

Given that limited high-grade evidence is available in the literature, double blind head-to-head trials are needed to further evaluate the role of thalidomide in relapsed or refractory bleeding GI AD lesions.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Waqar Ahmed at @DrWaqarAhmed1

Contributors: AB collected the information for the case report and wrote the manuscript. WA was the lead consultant and decision-maker in the patients’ care, and performed and photographed the endoscopy. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sami SS, Al-Araji SA, Ragunath K. Review article: gastrointestinal angiodysplasia—pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:15–34. 10.1111/apt.12527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boley SJ, Sammartano R, Adams A et al. . On the nature and etiology of vascular ectasias of the colon. Degenerative lesions of aging. Gastroenterology 1977;72:650–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clouse RE, Costigan DJ, Mills BA et al. . Angiodysplasia as a cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Intern Med 1985;145:458–61. 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360030098019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Junquera F, Saperas E, de Torres I et al. . Increased expression of angiogenic factors in human colonic angiodysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1070–6. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson CS, Gerson LB. Management of gastrointestinal angiodysplastic lesions (GIADs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:474–83. 10.1038/ajg.2014.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R et al. . Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy 2015;47:352–76. 10.1055/s-0034-1391855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhi-Zheng G, Hui-Min C, Yun-Jie G et al. . Efficacy of thalidomide for refractory gastrointestinal bleeding from vascular malformation. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1029–637. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]