Abstract

Infection is a common complication of solid organ transplantation. It is associated with an increased risk of acute cellular rejection and loss of graft function. The most common infections are due to bacteria and viruses, including transmission of cytomegalovirus from donor to recipient. In the past years, an increasing number of parasitic infections have been documented in transplant recipients. We describe the first reported case of intestinal Giardia lamblia transmission following simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation.

Background

Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation (SPK) is the preferred treatment option in type 1 diabetes with end-stage renal disease.1–6 Infection is a frequent complication after solid organ transplantation,2 3 7 it increases the risk of graft loss, and is associated with increased mortality and morbidity.1–3 8

Infections following solid organ transplantation are most often caused by bacteria or viruses.3 The prevalence and incidence of parasitic infections in transplant recipients are unknown since many patients are asymptomatic.9 10 However, published reports suggest that only 5% of infections are ascribed to human pathogenic parasites.9 10

Giardia lamblia is the most common parasitic infection in transplanted patients1 11 and has previously been identified in renal,9 10 intestinal12 and bone marrow recipients,13 including children with bone marrow transplants.14

G. lamblia is a flagellated protozoan parasite that invades the upper small intestine causing giardiasis. Human giardiasis is commonly observed worldwide. In developing countries, the reported overall incidence is between 20% and 30%, and in some populations a prevalence of 100% has been reported. In developed countries, the prevalence ranges from 3% to 7%.15 Giardia may exist as a cyst or as a trophozoite.15 16 Cysts are excreted with faeces from an infected host. Transmission occurs when cysts are ingested through contaminated food, water or by direct oral–faecal contact. Transmission may also occur from animals to humans, as some Giardia parasitic genotypes may infect several mammalian species including humans.15 16

When entering the first part of the proximal small intestine, the cysts transform into trophozoites, which colonise the gastrointestinal tract. Clinical manifestations of Giardia infection vary in severity. Some patients are asymptomatic,4 15 16 whereas others experience acute onset of symptoms including stomach pain, flatulence, steatorrhoea and diarrhoea. Symptoms usually begin 6–15 days following transmission.15 Giardia infections are usually self-limiting, but in patients with immune defects, it may present as chronic diarrhoea, anorexia, failure to thrive, growth retardation and cognitive dysfunction.15

Case presentation

A 37-year-old Danish man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease underwent a SPK with organs from a deceased donor, who originally came from the Middle East. The recipient's medical history included hypertension and microvascular diabetic complications including retinopathy, neuropathy and mild gastroparesis. He had no history of parasitic infections and no previous exposure to endemic areas of giardiasis.

The donor duodenal segment was anastomosed side-to-side to the native duodenal segment. Immediate function of both the kidney and the pancreas graft was observed with postoperative urine production and insulin-independency.

On the eighth postoperative day, a venous thrombosis was identified in the pancreas graft resulting in partial loss of pancreas graft function and insulin dependency. The thrombosis was believed to be caused by dehydration. The kidney graft function was excellent, and after 2 weeks, the plasma creatinine levels were within normal range. The patient’s immunosuppressive regimen at discharge consisted of tacrolimus (target level 6–10), mycophenylate mofetil (750 mg two times a day) and prednisolone. As infection prophylaxis, the patient was treated with sulfametoxizol and trimethoprim.

Shortly after transplantation, the patient had episodes of nausea, anorexia, stomach pain and symptoms of both diarrhoea and constipation associated with a 7 kg weight loss, causing a decline in body mass index from 20.5 kg/m2 before transplantation to 17.6 kg/m2.

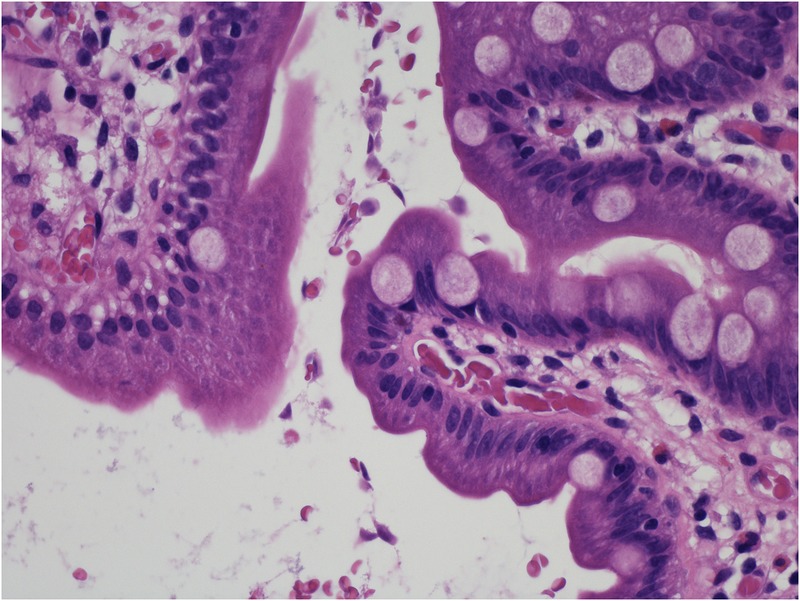

Fifty-one days after transplantation, the patient was admitted with nausea, vomiting, loose stools and fever. Stool cultures did not identify any pathogenic bacteria or viruses. A blood test for cytomegalovirus (CMV)-DNA was also negative. During the hospital stay, the patient was diagnosed with Escherichia coli septicaemia originating from the urinary tract. The infection was successfully treated with piperacillin/tazobactam, and the patient recovered, although persistent diarrhoea was noted at discharge; this was ascribed to the antibiotic treatment. Four days later, the patient was admitted with similar symptoms, but no fever. No pathogenic agents were identified in blood or stool samples, and the symptoms were interpreted as diabetic gastroparesis. During this hospital stay, the patient underwent endoscopic protocol biopsies of both, the donor and the recipient duodenal segments. The pathology revealed small, round cysts located in the lumen of the bowel of the donor and recipient duodenal biopsies, consistent with G. lamblia infection (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative image of a section from the recipient duodenal protocol biopsy (H&E staining). Several small, round cysts consistent with Giardia lamblia are located in the lumen of the bowel.

Subsequent stool microscopy confirmed Giardia cysts and trophozoites, and thus infection with G. lamblia. The patient was treated with metronidazole (500 mg three times a day for 10 days), resulting in relief of gastrointestinal symptoms, improvement in general health, weight gain and an increase in BMI to 20.4. After treatment, stool samples were negative for G. lamblia.

Discussion

The present case reports an early, post-transplant giardiasis in a SPK recipient residing in a non-endemic area and with no previous history of parasitic infections. The infection was identified in protocol biopsies performed about 2 months after transplantation, and was localised in donor and recipient duodenal tissue. Most likely this represents transfection at the time of transplantation, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported.

The patient had ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms, but these were ascribed to medication side effects (antibiotics) and diabetic gastroparesis. An early screening for parasitic infection may have allowed for earlier diagnosis; however, this was not initiated as the patient did not have a history of exposure. Non-invasive diagnosis of Giardia intestinal infection classically includes direct microscopy of fresh stools to look for characteristic cysts or possibly trophozoites. Additional, and possibly more sensitive stool tests, include immunoassays that detect antigens of cysts or trophozoites and nucleic acid amplification assays that detect Giardia DNA. To preserve donor confidentiality, no medical history or country of origin was noted in the patient files, which may have delayed the diagnosis.

In the past few years, there has been a reported increase in parasitic infections following solid organ transplantation.4 This may be due to increased globalisation.4 In our case, samples were no longer available to confirm a subclinical infection; however, the donor was originally from a part of the Middle East where giardiasis is endemic. Since the recipient had not been abroad and the incubation period was in accordance with the time of transplantation, infection was likely transmitted from the donor duodenal segment.

Persistent diarrhoea is common after solid organ transplantation, occurring in up to 20% of patients.8 It not only affects quality of life, but also increases the risk of malnutrition, number of hospital admissions and the risk of acute cellular rejection in kidney transplantation,8 17 possibly with reduced graft survival. Thus, rapid identification and correction of the cause are important.

Treatment with Mycophenolate Mofetil is the most common cause of diarrhoea in patients with transplant.18 Infectious diarrhoea is most often caused by CMV, Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter jejuni and novovirus,4 19 while G. lamblia and Cryptosporidium are the most common parasitic infections in patients with transplant.1

There are no published reports of the prevalence of giardiasis after solid organ transplantation; however, as globalisation increases and solid organ transplantation becomes more available around the world, parasitic infections, including G. lamblia, are likely to become more frequent among transplant recipients.4 19

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a likely transmission of G. lamblia from donor to recipient during SPK. This case also demonstrates the importance of searching for less common infectious agents in immunocompromised patients with unresolved symptoms of infection.

Learning points.

Giardia lamblia infection is a rare complication of solid organ transplantation.

In recent years, there has been a reported increase in parasitic infections following solid organ transplantation, possibly due to increased globalisation.

Transplanted and immunocompromised patients with specific or non-specific symptoms of infection should be tested for less common, infectious agents.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nankivell BJ, Kuypers DR. Diagnosis and prevention of chronic kidney allograft loss. Lancet 2011;378:1428–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60699-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel R, Paya CV. Infections in solid organ transplantation recipients. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997;10:86–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishman J. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2601–14. 10.1056/NEJMra064928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz BS, Mawhorter SD. AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Parasitic infections in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 2013;13(Suppl 4):280–303. 10.1111/ajt.12120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson P, Davis C, Larsen J et al. . American Diabetes Association, pancreas transplantation in type 1 diabetic. Diabetis Care 2004;27:S105 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.S105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morath DC, Schmied B, Mehrabi A et al. . Simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Clin Transplant 2009;23(Suppl 21):115–20. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman JA. The AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Introduction: infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009;9:3–6. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weclawiak H, Ould-Mohamed A, Bournet B et al. . Duodenal villous atrophy: a cause of chronic diarrhea after solid–organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 2011;11:575–82. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azami M, Sharifi M, Hejazi SH et al. . Intestinal parasitic infections in renal transplant recipients. Braz J Infect Dis 2010;14:15.–. 10.1016/S1413-8670(10)70004-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valar C, Keitel E, Prá RL et al. . Parasitic infection in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2007;39:460–2. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerri T, Forrest G. Gastrointestinal infections in immunocompromised hosts. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2006;22:18.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziring D, Tran R, Edelstein S et al. . Infections entertis after intestinal transplantation: incidens, timing, and outcome. Transplantation 2005;79:702–9. 10.1097/01.TP.0000154911.15693.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuen K, Patrick W, Liang R et al. . Clinical significance of alimentary tract microbes in bone marrow transplant recipients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1998;30:75–81. 10.1016/S0732-8893(97)00213-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaky J, Barners G, Bishop R et al. . Infectious diarrhea in children undergoing bone-marrow transplantation 1989;19:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halliez MC, Buret AG. Extra-intestinal and long term consequences of Giardia duodenalis infections. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:8974–85. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.8974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawrelak J. Giardiasis: pathophysiology and management. Altern Med Rev 2003;8:129–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunnapradist S, Neri L, Wong W et al. . Incidence and risk factors for diarrhea following kidney transplantation and association with graft loss and mortality. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:478–86. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maes BD, Dalle I, Geboes K et al. . Erosive enterocolitis in mycophenolate mofetil-treated renal-transplant recipients with persistent afebrile diarrhea. Transplantation 2003;75:665–72. 10.1097/01.TP.0000053753.43268.F0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Singer SM. Giardia duodenalis: the double-edged sword of immune responses in giardiasis. Exp Parasitol 2010;126:292–7. 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]