Abstract

Background

Shoulder arthroscopic surgeries have a high incidence of severe post-operative pain significant enough to interfere with recovery and rehabilitation. A regional anaesthetic technique combined with general anaesthesia reduces intra-operative requirements of anaesthesia and provides a better post-operative pain relief. As the commonly employed technique of interscalene brachial plexus block (ISB) is associated with potential serious complications, suprascapular nerve block (SSB) can be used as a safer alternative.

Methods and material

In this prospective study, 60 ASA 1 or 2 adult patients undergoing shoulder arthroscopic surgery were randomised into two groups – ISB and SSB. In group ISB, ISB with 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine mixed with 75 μg clonidine was given. In the SSB group SSB was given with 15 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 75 μg clonidine. Pain was assessed using visual analogue scale and verbal pain scale scores and time to first rescue analgesia was noted. We used Student's t test and Chi-square/Fisher Exact test and used a statistical software to compare data.

Results

In the present study, the mean duration of analgesia was 2.53 ± 2.26 h in SSB group compared to 7.23 ± 6.83 h in group ISB (p value < 0.05). Overall rescue analgesic requirements were higher in SSB group compared to ISB group (63.3% versus 40.0%) but this was statistically not significant (p value > 0.05).

Conclusion

Both interscalene and SSB can be used to provide intra-operative and post-operative analgesia in patients undergoing shoulder arthroscopy.

Keywords: Shoulder arthroscopy, Suprascapular nerve block, Interscalene block, Anaesthesia, Post-operative analgesia

1. Introduction

These days most of the shoulder joint surgeries are done arthroscopically in ambulatory settings as most patients like to have minimum scar, duration of surgery and hospital stay. Arthroscopic shoulder surgery has a 45% incidence of severe intra-operative and post-operative pain1 that is often significant enough to interfere with initial recovery and rehabilitation, and which can be difficult to manage without large dose opioids.2 Regional anaesthetic techniques have the ability to control pain effectively, both at rest and on movement, allowing earlier mobilisation without the adverse effects of opioids.3

General anaesthesia (GA) with a regional nerve block reduces intra-operative requirements of anaesthesia, resulting in rapid recovery and improvement in the quality of post-operative pain relief in arthroscopic shoulder surgeries.3

A commonly used nerve block technique for this purpose is interscalene brachial plexus block (ISB) and its efficacy is well established. Even in a small dose, single dose ISB provides significant analgesia.2, 4, 5 However, ISB is associated with potential serious complications, which include inadvertent epidural and spinal anaesthesia, vertebral artery injection, paralysis of vagus, recurrent laryngeal and cervical sympathetic nerves block,6 etc. Phrenic nerve block occurs in all patients undergoing ISB.7, 8, 9, 10

To avoid these complications of ISB, an alternative technique of suprascapular nerve block (SSB) has been suggested for post-operative analgesia after shoulder arthroscopy. The suprascapular nerve provides sensory fibres to 70% of the shoulder joint. While SSB cannot be used alone for surgery, it provides excellent pain relief and induces fewer side effects than intravenous patient controlled analgesia with morphine.3, 11

Various additives to local anaesthetic solutions have been used to prolong the duration and increase the efficacy of blocks.12, 13 Clonidine has been shown to increase the duration of local anaesthetic action and prolong post-operative analgesia when included in single-injection nerve blocks.14 Clonidine appears to be superior to epinephrine in enhancing the duration of plexus blockade with bupivacaine and offers better haemodynamic stability15 while avoiding the potential risks of epinephrine.16

2. Methods

The aim of our prospective randomised study was to evaluate and compare the intra-operative and post-operative analgesic efficacy of SSB and interscalene block in patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery of shoulder joint under GA.

After institutional approval and informed written consent, 60 patients in the age group of 18–60 years of either sex, with ASA physical status 1 or 2, scheduled to undergo elective arthroscopic shoulder surgeries under GA were randomised into two groups (30 each). Patients were excluded if they were unable to understand procedure and/or pain scales, had a body weight <50 kg or >100 kg, had pre-existing neurological deficit or pulmonary disease, diabetes, local skin infection or coagulation disorders. Patients with history of hypersensitivity to any of the medications used in the anaesthetic procedure or opioid or clonidine therapy in pre-operative period were also excluded. All patients were evaluated in the pre-anaesthetic clinic with a detailed history and relevant investigations were done.

Pre-operatively, patients were instructed in the use of visual analogue scale (VAS) and the verbal pain scale (VPS) for pain, nausea and vomiting, and sedation scores. Pre-operative baseline VAS and VPS scores were assessed 1 h before surgery at rest and on abduction of the shoulder and maximum score was recorded.

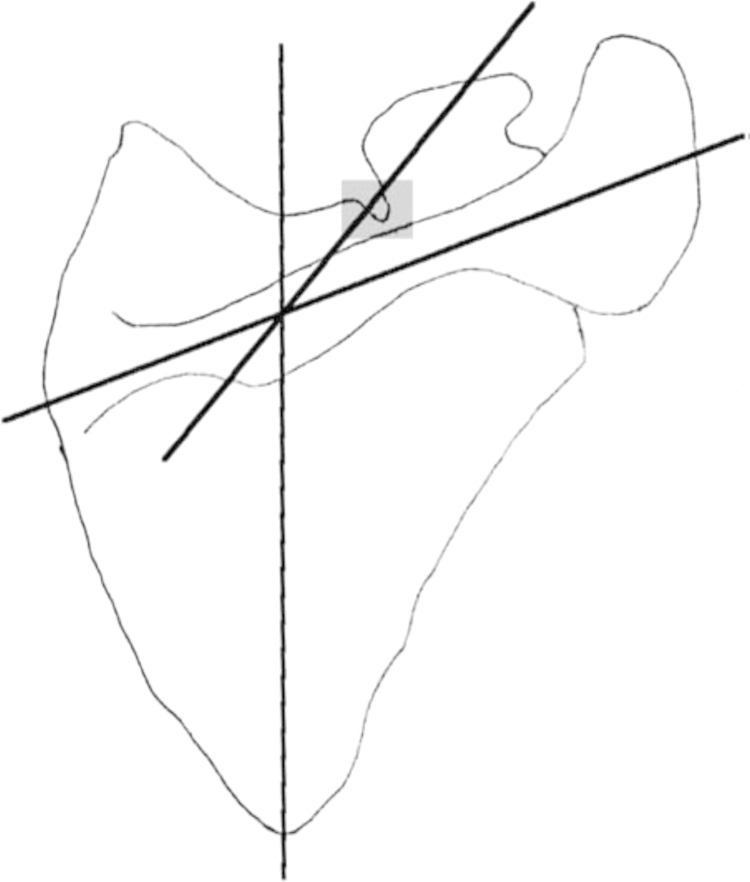

In group SSB, nerve block was performed at the suprascapular notch with the patient sitting up and leaning forward using the posterior approach described by Moore.17 A line was drawn along the length of the spine of the scapula and was bisected with a vertical line, parallel to vertebral spine, forming four quadrants. After skin preparation and draping, the angle of the upper outer quadrant was bisected and the skin was infiltrated with 2 ml of 1% lignocaine at a point 2.5 cm along this line of bisection. Under sterile conditions, a short bevelled 22 G insulated needle was introduced perpendicular to the skin. By using peripheral nerve stimulator (Plexygon, Vygon, France), the suprascapular nerve was located using a 100 mm insulated needle by stimulation with a 0.5 mA (impulse frequency 2 Hz and duration 300 μs) current. Stimulation of the suprascapular nerve caused contraction of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles and led to an abduction and external rotation of the arm respectively. In most patients, a loss of resistance was noticed as the needle slid into the suprascapular notch. At this point 15 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 75 μg of clonidine was injected after repeated negative aspiration. An additional 5 ml was infiltrated subcutaneously over the shoulder region to block cutaneous sensory branches of C3 and C4 nerve roots (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Superficial landmarks for the suprascapular nerve block. Grey rectangle represents the introduction point of the needle.

Fig. 2.

Surface landmarks for site of needle entry in suprascapular block.

In group ISB, block was performed following Winnie's landmarks.11, 18 Using this technique, the plexus was approached at the C6 level (cricoid cartilage) where the roots of the brachial plexus (C5 through T1) pass between the anterior and middle scalene muscles in interscalene groove. The direction of the needle is medial, dorsal, and caudal with the needle entry approximately 60° from the sagittal plane. A 22 G, 50 mm needle connected to a peripheral nerve stimulator, was introduced near the plexus sheath. Its position was judged adequate when a group of muscles distal to the deltoid were stimulated with a threshold stimulation of 0.5 mA. After negative aspiration test for blood, 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 75 μg of clonidine was injected.

All patients received standard GA using endotracheal intubation using fentanyl 2 μg/kg, propofol 2–2.5 mg/kg body weight and vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg. Vital signs (continuous ECG with heart rate, non-invasive blood pressure at every 5 min intervals, SpO2, etCO2) were monitored throughout the anaesthesia. Relaxation was maintained with top-up dose of vecuronium as required and supplemental doses of fentanyl (50 μg, until 30 min before end of surgery) were administered if heart rate and/or mean arterial blood pressure values exceeded 20% of baseline values. At the end of the surgery, reversal of neuromuscular block was accomplished by neostigmine and glycopyrrolate, and extubation was done, when patient was fully awake and breathing spontaneously.

All patients were shifted to the post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) for monitoring and observation. The earliest point in time at which patient was able to communicate was taken as ‘Zero Hour’. Post-operative pain at rest and on abduction of shoulder was assessed using self rating VAS ranging from 0 to 10 (0 = no pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain) and VPS ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = no pain, 1 = mild pain, 2 = moderate pain, and 3 = severe pain) at 0, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, and at 24 h. On experiencing pain at VAS ≥ 4, the patient received diclofenac sodium 75 mg im as the “First Rescue Analgesic”. Time elapsed between the nerve block and first rescue analgesic injection was noted and was considered as duration of analgesia produced by the nerve block. The number of rescue analgesic injection(s) received by patient in 24 h was noted.

Descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out in this study. Student's t test (two tailed, independent) has been used to find the significance of study parameters on continuous scale between two groups (inter-group analysis) on metric parameters. Chi-square/Fisher Exact test has been used to find the significance of study parameters on categorical scale between two or more groups. The Statistical software namely SAS 9.2, SPSS 15.0, MedCalc 9.0.1 were used for the analysis of the data.

3. Observation and results

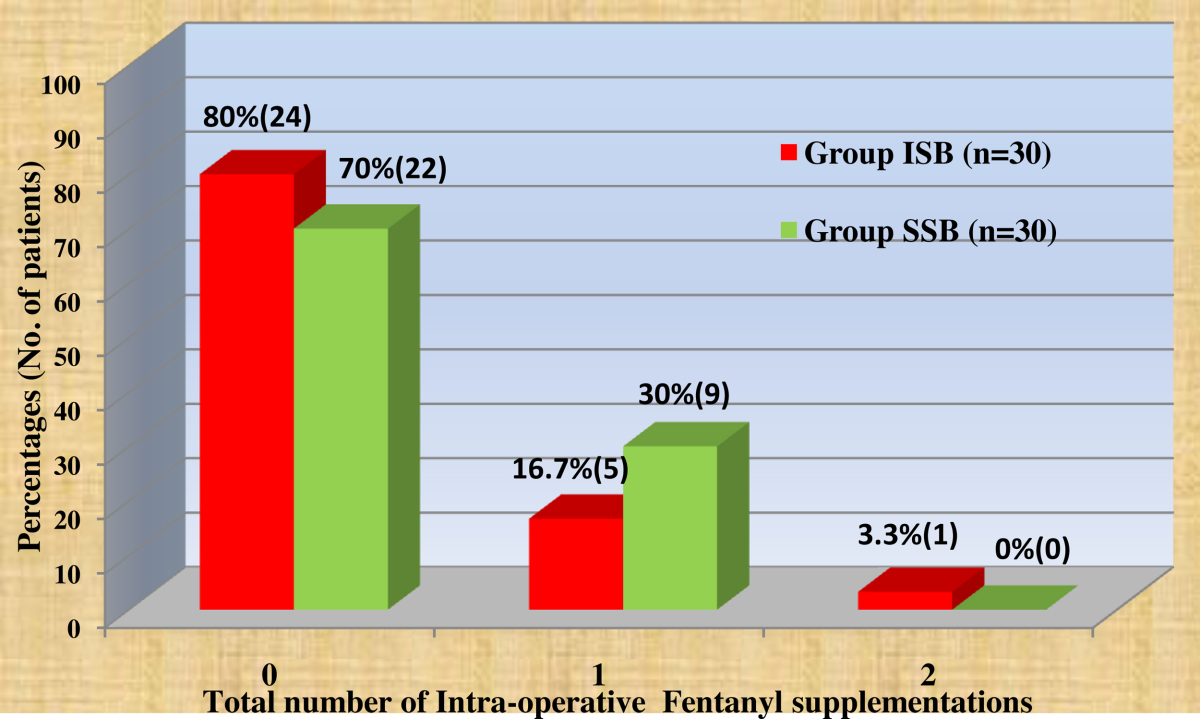

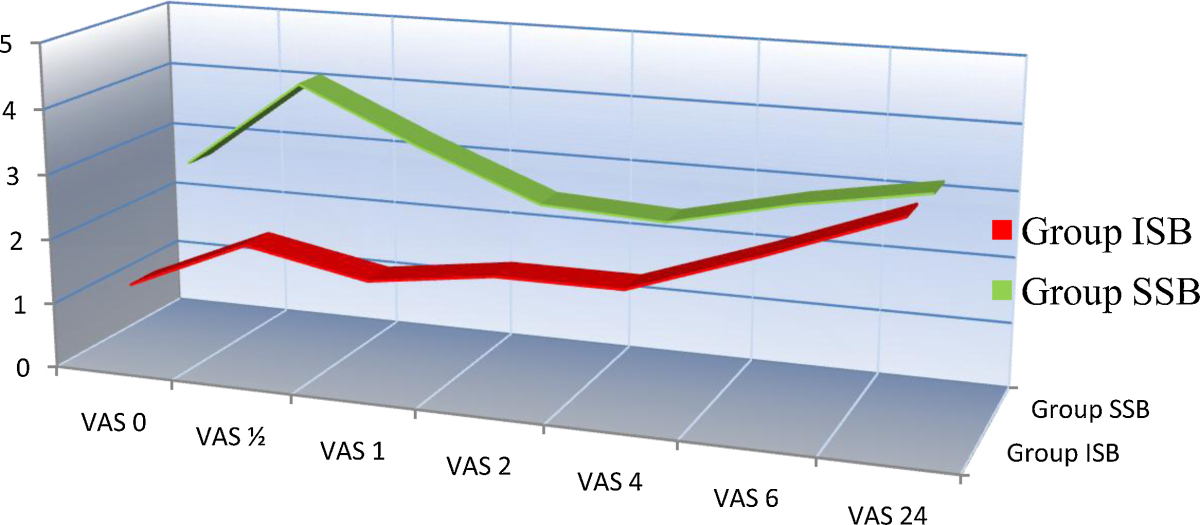

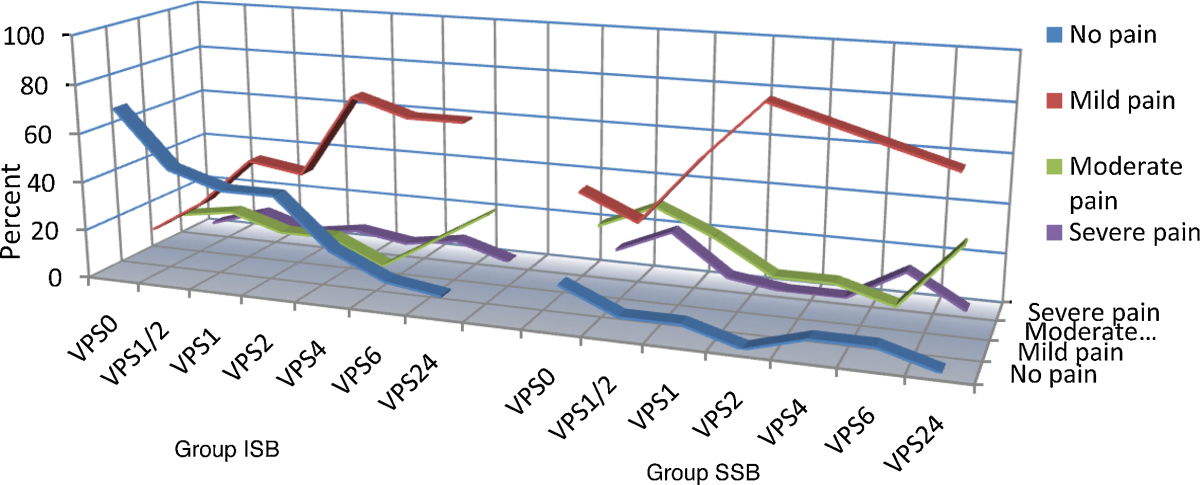

The demographic data were comparable in all groups, and duration of surgery was almost similar between groups. The number of patients needing fentanyl supplementations intra-operatively was comparable between groups with 6 (20%) in group ISB compared to 9 (30%) in group SSB required supplementation. In the PACU, all patients in Groups SSB and ISB had objective evidence (presence of a sensory block) of the associated block. Mean VAS scores and VPS scores at rest and on movement and supplemental analgesia are presented in graphs (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3).

Table 1.

Comparison of VAS scores between groups.

| VAS | Group ISB | Group SSB | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS 0 | 1.23 ± 2.23 | 2.70 ± 2.20 | 0.001 |

| VAS ½ | 2.03 ± 2.53 | 4.10 ± 2.16 | <0.001 |

| VAS 1 | 1.67 ± 1.86 | 3.27 ± 1.48 | <0.001 |

| VAS 2 | 1.93 ± 2.35 | 2.53 ± 0.82 | 0.002 |

| VAS 4 | 1.93 ± 1.48 | 2.43 ± 1.10 | 0.096 |

| VAS 6 | 2.60 ± 1.55 | 2.87 ± 1.31 | 0.708 |

| VAS 24 | 3.33 ± 1.29 | 3.20 ± 0.99 | 0.599 |

Table 2.

Total number of intra-operative fentanyl supplementations.

Table 3.

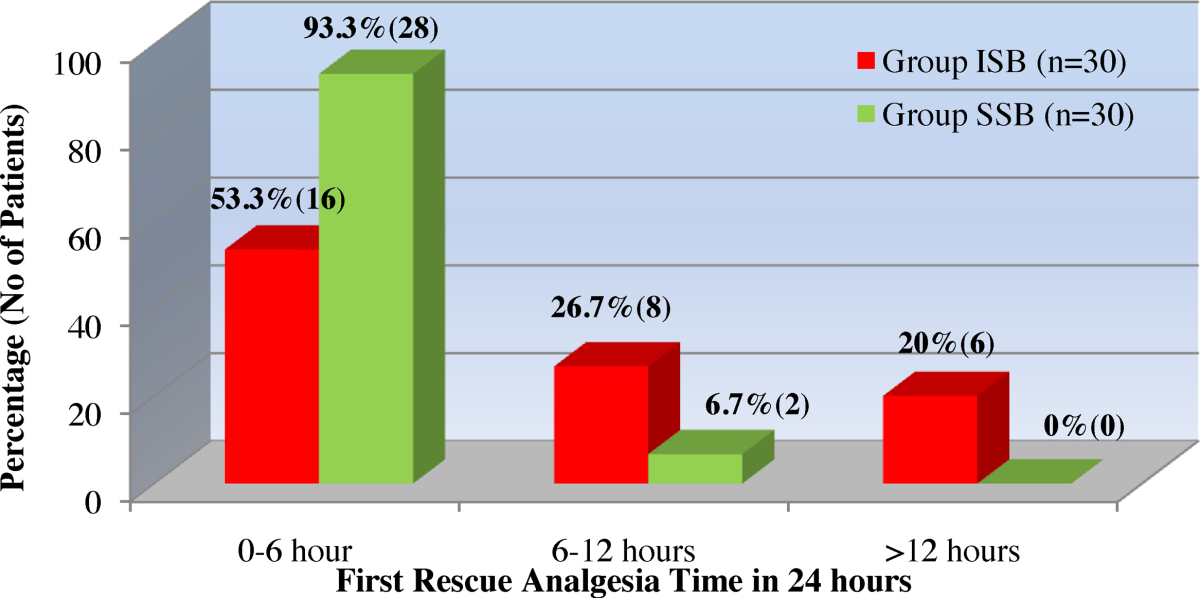

First rescue analgesia time in 24 h.

Intra-operative vital parameters such as heart rate, non-invasive blood pressure, peripheral oxygen saturation and end tidal carbon dioxide with ventilatory frequency kept same in all patients showed no significant inter-group differences. First rescue analgesia time considered as mean duration of analgesia was significantly less in Group SSB compared to Group ISB (2.53 h versus 7.23 h) (p value < 0.05) with 28 out of 30 patients in Group SSB requiring rescue analgesia within 6 h post-operatively compared to 16 patients in Group ISB. The total number of rescue analgesic requirement in 24 h follow-up in our study in group ISB 16 patients received one rescue analgesic, 12 patients received two rescue analgesics, and two patients received none compared to group SSB, where 11 patients received one rescue analgesic, and rest of 19 patients (63.3%) received two rescue analgesic which was statistically insignificant between groups (p value > 0.05).

VAS was recorded at specified intervals between the two groups post-operatively. Group SSB showed higher mean VAS scores compared to Group ISB during first 6 h, which was statistically significant till first 2 h. Verbal pain scores between groups showed statistical significant values up to 4 h interval, at 6 h interval scores were comparable between the groups and at 24 h interval scores were almost similar (Table 4, Table 5).

Table 4.

Comparison of VAS scores between groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of Verbal pain score (VPS) between two groups of patients.

4. Discussion

Anaesthesia techniques combining regional anaesthesia and GA can result in additive or synergistic effects of two or more drugs that relieve pain by different mechanisms and results in decreased requirements analgesics post-operatively. Many studies have demonstrated that ISB is the most efficient regional analgesic technique in shoulder arthroscopic surgery. ISB, alone or supplemented with superficial cervical plexus block to ensure the blockade of the supraclavicular nerve results in success rates of 87–100%.3 However it is associated with potentially serious complications include inadvertent epidural and spinal anaesthesia, vertebral artery injection, paralysis of vagus, recurrent laryngeal, and cervical sympathetic nerve,5 pneumothorax6 and injury to the brachial plexus. Phrenic nerve block occurs in all patients undergoing interscalene nerve block.7, 8, 9, 10

To avoid these complications of ISB an alternative technique of SSB has been suggested for post-operative analgesia for shoulder arthroscopy. Therefore, we planned to compare SSB with ISB with regard to efficacy and duration of post-operative analgesia and side effects associated with both the techniques.

In our study the mean duration of analgesia was 2.53 ± 2.26 h in SSB group compared to 7.23 ± 6.83 h in group ISB (p value < 0.05) which is significantly shorter in SSB group. Similarly Neal et al.19 observed mean duration to be 220 min (3.67 h) in SSB group. Ritchie et al.,3 demonstrated that in the immediate post-operative period, a 51% reduction in demand and a 31% reduction in consumption of morphine delivered by a patient-controlled analgesic system in SSB group compared placebo group. In our study, the overall rescue analgesic requirements were higher in SSB group compared to ISB group (63.3% versus 40.0%) and this was statistically not significant with p value > 0.05.

There was a modest increase in post-operative pain reported with the SSB group in our study which was also described by Ritchie et al.3 and Singelyn et al.11 in their studies. This has to be anticipated, as the supra scapular nerve supplies only 70% of the sensory fibres to the joint and capsule. However, because the duration of analgesia varies widely among patients, it is difficult to predict, if an individual patient will experience prolonged pain relief.

Adding clonidine to regional anaesthetic solution provided good haemodynamic conditions15 during the surgery with mean non-invasive blood pressure well maintained around 80 mm Hg, which was essential to provide better surgical field during arthroscopy without any adverse effects in both intra- and post-operative periods.

ISB combined with GA20 remains an useful technique for providing both intra-operative and post-operative analgesia in shoulder arthroscopic surgeries. When in an individual patient the risk of complications are considered to be high using interscalene approach, SSB can be used as an alternative technique.

We conclude that our prospective randomised study demonstrated efficacy of interscalene block with GA for both intra- and post-operative analgesia in arthroscopic shoulder surgeries. However SSB with GA is also a safe and simple alternative technique for this purpose. Clonidine at dose 1–1.5 μg/kg body weight can be safely added to local anaesthetic solutions for providing good haemodynamic and surgical conditions without any significant adverse effects in both the techniques.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Footnotes

Presented as ‘Free Paper’ In “Isacon-2012 Indore”, Madhya Pradesh. Organisation: Indian society of Anaesthesiologists; Place: Indore, Madhya Pradesh; Date: December 2012.

References

- 1.Moote C. Random double-blind comparison of intra-articular bupivacaine and placebo for analgesia after outpatient shoulder arthroscopy (abstract) Anesthesiology. 1994;81:A49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Kaisy A., McGuire G., Chan V.W. Analgesic effect of interscalene block using low-dose bupivacaine for outpatient arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:469–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritchie E.D., Tong D., Chung F. Suprascapular nerve block for postoperative pain relief in arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a new modality? Anesth Analg. 1997;84(6):1306–1312. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199706000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurila P.A., Lopponen A., Kanga-Saarela T. Interscalene brachial plexus block is superior to subacromial bursa block after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:1031–1036. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krone S.C., Chan V.W., Regan J. Analgesic effects of low-dose ropivacaine for interscalene brachial plexus block for outpatient shoulder surgery – a dose-finding study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:439–443. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2001.25914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conn R.A., Cofield R.H., Byer D.E. Interscalene block anesthesia for shoulder surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urmey W.F., Gloeggler P.J. Pulmonary function changes during interscalene brachial plexus block: effects of decreasing local anesthetic injection volume. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:244–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urmey W.F., Talts K.H., Sharrock N.E. One hundred percent incidence of hemidiaphragmatic paresis associated with interscalene brachial plexus anesthesia as diagnosed by ultrasonography. Anesth Analg. 1991;72(4):450–498. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urmey W.F., McDonald M. Hemidiaphragmatic paresis during interscalene brachial plexus block: effects on pulmonary function and chest wall mechanics. Anesth Analg. 1992;74(3):352–357. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pere P. The effect of continuous interscalene brachial plexus block with 0.125% bupivacaine plus fentanyl on diaphragmatic motility and ventilatory function. Reg Anesth. 1993;18(2):93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singelyn F.J., Lhotel L., Fabre B. Pain relief after arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a comparison of intraarticular analgesia, suprascapular nerve block, and interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:589–592. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000125112.83117.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy D.B., McCartney C.J., Chan V.W. Novel analgesic adjuncts for brachial plexus block: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1122–1128. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200005000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenach J.C., De Kock M., Klimscha W. alpha (2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984–1995) Anesthesiology. 1996;85:655–674. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iskandar H., Guillaume E., Dixmérias F. The enhancement of sensory blockade by clonidine selectively added to mepivacaine after midhumeral block. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:771–775. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200109000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culebras X., Van Gessel E., Hoffmeyer P. Clonidine combined with a long acting local anesthetic does not prolong postoperative analgesia after brachial plexus block but does induce hemodynamic changes. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:199–204. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sia S., Lepri A. Clonidine administered, as an axillary block does not affect postoperative pain when given as the sole analgesic. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1109–1112. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore D.C. Block of the suprascapular nerve. In: Thomas C.C., editor. 4th ed. vol. 9. Springfield; 1979. pp. 300–303. (Regional Nerve Block). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winnie A.P. Interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 1970;49(3):455–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neal J.M., McDonald S.B., Larkin K.L. Suprascapular nerve block prolongs analgesia after nonarthroscopic shoulder surgery but does not improve outcome. Anesth Analg. 2003;96(April (4)):982–986. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000052380.69541.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandl F., Taeger K. The combination of general anesthesia and interscalene block in shoulder surgery. Anaesthesist. 1991;40(October (10)):537–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]