Abstract

Aims:

To assess the diagnostic value of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 (cytokeratin 19 fragments) in serum and pleural fluid in non small cell lung cancer with malignant pleural effusion (MPE).

Settings and Design:

Two subsets of patients were recruited with lymphocytic exudative effusion, one subset constituted diagnosed patients of NSCLC with malignant pleural effusion and the other subset of constituted with Tubercular pleural effusion.

Materials and Methods:

CYFRA 21-1 and CEA levels were measured using Electrochemilumiscence Immunoassay (ECLIA). The test principle used the Sandwich method. For both the tests, results are determined via a calibration curve which is instrument specifically generated by 2 - point calibration and a master curve provided via reagent barcode.

Statistical Analysis Used:

All data are expressed as means ± SD and percentage. All the parametric variables were analysed by student-t test where as non parametric variables were compared by Mann-Whitney U-test Statistical significance was accepted for P values < 0.05. Software used were SPSS 11.5, and MS excel 2007. In order to compare the performance of the tumor markers, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed and compared with area under the curve (AUC). The threshold for each marker was selected based on the best diagnostic efficacy having achieved equilibrium between sensitivity and specificity.

Results:

In cases serum CYFRA21-1 levels had mean value of 34.1 ± 29.9 with a range of 1.6-128.3 where as in controls serum CYFRA21-1 levels had mean value of 1.9 ± 1.0 with a range of 0.5–4.7. In cases serum CEA levels had mean value of 24.9 ± 47.3 with a range of 1.0, 267.9 where as in controls serum CEA levels had mean value of 1.9 ± 1.4 with a range of 0.2-6.8. The difference in the means of serum CYFRA 21-l (P = 0.000) and CEA (P = 0.046) were statistically significant. In cases pleural fluid CYFRA21-1 levels had mean value of 160.1 ± 177.1 with a range of 5.4–517.2 where as in controls pleural fluid CYFRA21-1 levels had mean value of 15.9 ± 5.7 with a range of 7.2-29.6. In cases CEA pleural fluid levels had mean value of 89.8 ± 207.4 with a range of 1.0–861.2 where as in controls CEA levels had mean value of 2.5 ± 2.3 with a range of 1–8.9. The difference in the means of CYERA 21-1 (P = 0.001) between cases and controls is statistically significant.

Conclusions:

CYFRA21-1 (serum - pleural fluid) is a sensitive marker for NSCLC with sensitivity of 96.7%, highest of any combination [Serum (CYFRA 21-1 - CEA). CEA (Serum + Pleural Fluid), Pleural Fluid (CYFRA 21-1 + CEA)] and specificity of 77.8%. Levels of CYFRA21-l (serum + pleural fluid) are increased in malignant pleural effusion, so it is better to be used in suspicious malignant pleural effusion showing negative cytology, particularly in the absence of a visible tumor and or unsuitability for invasive procedure.

Keywords: Carcinoembryonic antigen, cytokeratin 19 fragments, malignant pleural effusion, nonsmall cell lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer represents 19.4% of all cancer related deaths.[1,2] It is a major health problem in Kashmir valley and constitutes 9.9% of all cancers here. It is the second common malignancy among males.[3] Pleural effusion is its common clinical presentation. Approximately, 20% of all pleural effusions are due to malignancy, and 50% of these are due to primary lung cancer.[4] A malignant pleural effusion (MPE) may be initial presentation of cancer in 10–50% of patients.[5]

Tumor deposits first establishes in the pleural space, spread along the parietal pleural membrane thereafter stimulate the release of chemokines that increase vascular and pleural membrane permeability thereby promoting pleural effusion.[6,7] Tumor markers are substances usually of peptide nature secreted by tumor cells or by host in response to a tumor. Pleural fluid is suitable medium to study the release of tumor markers. Many studies showed that pleural fluid had more levels of tumor markers than serum.[8] Tumor markers are normally absent or present in very small amount in serum and pleural fluid and thus serve as diagnostic tool in MPE.[9] Tumor marker is noninvasive tests to screen for the malignancy.

Tumor markers have high sensitivity in diagnosing cytologically negative effusion. By increasing number of tumor markers in panel, sensitivity increases to 90% and specificity as high as 95%, comparable to that of thoracoscopy (90%).[8] When measured serially after the diagnosis is established, they may aid in assessing response to treatment, in monitoring spontaneous course of illness and in keeping surveillance for tumor recurrences.[10]

Tumor markers fall in several categories:[11]

Oncofetal proteins

Structural proteins

Enzymes

Cell membrane components

Secreted proteins

Hormones

Other tumor associated antigens.

The most commonly used markers investigated in lung cancer are:

Neuron specific enolase (NSE)

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

Cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA 21-l)

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) antigen

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125)

Tissue polypeptide antigen

Tissue polypeptide specific antigen

CA 19-9

CA 15-3 10

ProGRP[12]

Tumor M2-PK.[13]

Several tumor markers in pleural fluid have been evaluated to distinguish malignant effusion from benign. CEA has been studied the most and has been shown to be very specific, but its sensitivity remains approximately 29–77% with variable cut-off values.[14,15] NSE is known as a serum marker of small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), and SCLC with pleural effusion was associated with elevated pleural fluid NSE.[16,17] However, the sensitivities of pleural fluid NSE for the diagnosis of malignant effusion from carcinomas including SCLC were relatively low.[18,19]

Serum CYFRA 21-1 have been shown to be the most sensitive tumor marker in non-SCLC (NSCLC), particularly the squamous cell type. In several reports’[19,20,21,22,23,24,25] on the use of pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 for the diagnosis of malignant effusion, the cut-off values varied from 8 to 175 ng/mL and the sensitivities varied from 22% to 91%.

Cytokeratin 19 fragment

Cytokeratins belong to the intermediate filament proteins, which are the major component of cell skelton.[26,27] There are around 20 different cytokeratins with a molecular weight ranging from 40 to 70 kd.[28] Cytokeratin 19 has molecular weight of 30.000 daltons. CYFRA 21-1 measures a fragment of cytokeratin 19. Unlike original cytokeratins, fragments of intermediate filaments are soluble in serum and can therefore be detected and measured with monoclonal antibodies. Preliminary investigations reveal CYFRA 21-1 shows a good specificity, sensitivity profile in bronchogenic carcinoma especially squamous cell type.[29]

Carcinoembryonic antigen

It is a glycoprotein of molecular weight 180 kd. lt is a single chain glycoprotein containing 30–70% weight percentage of carbohydrate. lt is one of the carcino-fetal antigen produced during fetal development. CEA is one the first tumor markers to be described and has relatively high sensitivity for advanced adenocarcinomas.[30] CEA levels is elevated in many malignancies such as digestive tract cancer, breast cancer jung cancer, metastatic disease of liver, pancreatic carcinoma, and medullary carcinoma of thyroid. However, CEA level is also increased in nonmalignant disorders too. Sensitivity of CEA is greater and serum CEA concentrations are higher in adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma lung.[31] The normal range of CEA in adult nonsmoker is <6.5 and in smoker <5.0 ng/ml, respectively.

This study is important as few studies are done on tumor markers in lung cancer in India as well as Kashmir and is first of its kind in MPE in lung cancer in Kashmir. Few data is available on tumor marker in our country and most of data is from Western countries. Our data is limited and needs to be researched. Western data has different cut-off values, and we need to establish our own cut-off values in view of ethnically different population. Previous studies involved heterogenous pathologic conditions, which included mesothelioma, lymphoma, metastatic lung cancer, and primary lung cancer.[32] In addition, patients with tuberculosis, parapneumonic effusion, empyema, and heart failure were enrolled together as benign control subjects. These make comparison of the results difficult and generalization not possible.

In the present study, we evaluated the diagnostic utility of each tumor marker, CEA, and CYFRA 21-1, in serum and pleural fluid as a marker of NSCLC by comparing with those of tuberculous pleurisy. In addition, the clinical value of a combination of these tumor markers was assessed.

Aims and objectives

To assess the diagnostic value of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in serum and pleural fluid in NSCLC with MPE

To assess the sensitivity and specificity of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in serum and pleural fluid in NSCLC cancer with MPE

To asses if combination values of tumor markers increase their diagnostic utility in MPE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Two subsets of patients were recruited with lymphocytic exudative effusion, one subset constituted diagnosed patients of NSCLC with MPE and the other subset of constituted with tubercular pleural effusion.

Study design

A Tertiary Care Center, 750 bedded hospital catering the population of Jammu and Kashmir State. It was a case control study.

Inclusion criteria for cases

Effusions were considered malignant if malignant cells were found on cytologic examination or in a biopsy specimen. Only specimens histologically diagnosed as primary NSCLC were considered. Malignancies due to any other causes were excluded.

Inclusion criteria for controls

Tuberculous pleurisy was diagnosed if one of the following criteria was met: Identification of acid-fast Bacillus (AFB) in pleural fluid, caseous granulomas in a pleural biopsy specimen, polymerase chain reaction for AFB positive and a high level of pleural fluid adenosine deaminase (40 U/L).

Exclusion criteria

Patients having renal failure. Patients who refused for a detailed examination and who refused giving a valid consent for serum and pleural fluid sample. Patients having bilirubin >65 mg/dl, lipemia >1500 mg/dl, and rheumatoid factors concentration >1500 IU/M1 were excluded from our study, as these factors cause interference in computation of marker levels.

History and detailed examination

Clinical parameters were recorded according to proforma given in the index. A special focus was on smoking in pack years or quantity of tobacco consumed in grams per day in hukka smokers. Examination of patients included a general physical examination and a systemic examination. Performance status was evaluated using Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale; it is five point system that is simple and easy to apply to clinical practice.

Routine investigations

Hemogram: Hemoglobin (Hb), Total leukocyte count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Liver function tests: Bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum albumin. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), chest X-ray, computed tomography chest, ultrasonography abdomen and chest, bronchoscopy, and histopathological examination of the specimen. If required CT guided biopsy, open lung biopsy, pleural biopsy, node biopsy, and thoracoscopic biopsy was done.

Special investigations

Serum and pleural fluid CEA and CYFRA 21-1 levels.

Cytokeratin 19 fragment levels

CYFRA 21-1 levels were measured using electrochemilumiscence immunoassay (ECLIA). The kit is manufactured by Roche diagnostics. The kit was stored at 2–8°C. Samples were stored at −70°C in the Immunology Department, SKIMS, Srinagar. The test principle used the Sandwich method.

Carcinoembryonic antigen levels

CEA levels were measured using ECLIA. The kit was manufactured by Roche diagnostics. The kit was stored at 2-8°C Samples were stored at −70°C in the Immunology Department, SKIMS, Srinagar. The test principle used the Sandwich method. For both the tests, results are determined via a calibration curve which is instrument specifically generated by 2-point calibration and a master curve provided via reagent barcode. In calibrator, two calset cal-1 and cal-2 are provided having two different concentrations. They are bar coded and are analyzed in Elecsys Immunosassay Analyzer (ROCHE, GERMANY). Accuracy is checked by quality control.

Limitations-interference

The assay is unaffected by icterus (bilirubin <65 mg/dl), hemolysis (Hb <2.2 g/dl), lipemia (intralipid <1500 mg/dl), and biotin <120 pg/ml. XO interference was observed from rheumatoid factors up to a concentration of 1500 IU/M1. In our study, these limitations were excluded. Prior to any therapy, blood and pleural fluid were collected from each patient on the same day. Serum and pleural fluid supernatant were obtained by centrifugation at 1800° - for 10 min and stored at −70°C (refrigerator-REVCO made in USA) in the Immunology Department, SKIMS, Srinagar, until tumor markers were assayed using commercial immunoassay kits. In both pleural fluid and serum, tumor markers were determined blind of information concerning the definitive diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and percentage. All the parametric variables were analyzed by Student's t-test whereas nonparametric variables were compared by Mann–Whitney U-test statistical significance was accepted for P < 0.05. Software used were SPSS (www.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss) 11.5, and MS Excel 2007. In order to compare the performance of the tumor markers, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed and compared with area under the curve (AUC). The threshold for each marker was selected based on the best diagnostic efficacy having achieved equilibrium between sensitivity and specificity.

RESULTS

A total of 48 patients with pleural effusions were studied, with age ranging from 30 to 85 years. Thirty patients were diagnosed as malignant effusion and 18 as benign (tubercular) which served as controls. The mean age in cases was 59.6 ± 10.5 years with range from 38 to 85 years. Out of the 30 cases, 23 (76.7%) patients were >50 years of age. The mean age of controls was 45.8 ± 9.9 years (range 30–65); out of the controls, only six (33.3%) patients were >50 years of age. A statistically significant association of malignant effusions was seen with age more than 50 years (P = 0.003).

Sixty percentage of the cases (18 of 30) and 72% of the controls (13 of 18) were males. Gender difference between the two groups was insignificant (P = 0.396). The most common symptoms in the cases was breathlessness (n = 27; 90%), followed by chest pain (n = 9; 30%), and hemoptysis (n = 5; 16.7%). A statistically significant association was seen between breathlessness and malignant effusions (P = 0.000). History of smoking was more commonly present in patients of malignant effusions (n = 24; 80%) compared to the controls (n = 7; 38.9%) as was the case with > 20 pack years of smoking (cases; n = 18; 75%: Controls; n = l; 14.3%>), and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.004). The performance score (ECOG score) of most of the cases at presentation was two (17; 56.7%) and three (13; 43.3%>). Higher score at presentation was significantly associated with malignant effusions (P = 0.000). The duration of symptoms (P = 0.364), side of effusion (0.301), and weight loss (0.817) has no significant association with malignancy but the P value of grade of effusion was significant (P = 0.001), with higher grades (moderate and massive) favoring malignancy.

A statistically significant difference of the means of serum LDH (P = 0.035) was observed between cases (465.2 ± 133.0 [186, 775]) and controls (391.9 ± 114.7 [138, 586]). All the 30 patients of malignant effusion were malignant cells positive fulfilling the criteria for inclusion in our study. All the cases were subjected to bronchoscopy but only 18 (60%) had positive findings on bronchoscopy. Histological diagnosis was confirmed by CT guided biopsy in 16 (53.4%) patients, and 14 (46.6%) were confirmed on bronchoscopic biopsy. Five patients were having metastatic deposits to peripheral lymph nodes. On histology, 23 (76.7%) were squamous cell lung carcinoma and 7 (23.3%) were adenocarcinomas of lung.

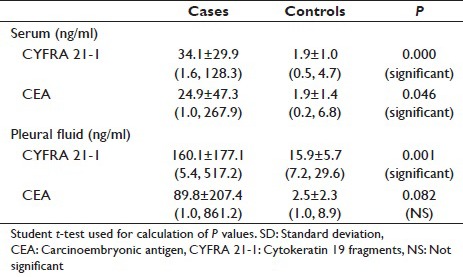

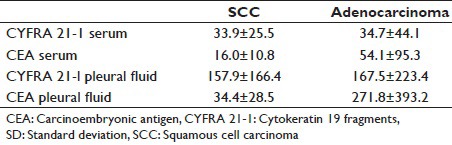

In cases, serum CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 34.1 ± 29.9 with a range of 1.6–128.3 whereas in controls serum CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 1.9 ± 1.0 with a range of 0.5–4.7 [Table 1]. In cases, serum CEA levels had mean value of 24.9 ± 47.3 with a range of 1.0, 267.9, whereas in controls serum, CEA levels had mean value of 1.9 ± 1.4 with a range of 0.2–6.8 [Table 1]. The difference in the means of serum CYFRA 21-l (P = 0.000) and CEA (P = 0.046) were statistically significant. In cases, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 160.1 ± 177.1 with a range of 5.4–517.2, whereas in controls, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 15.9 ± 5.7 with a range of 7.2-29.6. In cases, CEA pleural fluid levels had mean value of 89.8 ± 207.4 with a range of 1.0–861.2, whereas in controls, CEA levels had mean value of 2.5 ± 2.3 with a range of 1-8.9. The difference in the means of CYERA 21-1 (P = 0.001) between cases and controls is statistically significant [Table 1].

Table 1.

Tumor markers in serum and pleural fluid with mean±SD (minimum, maximum)

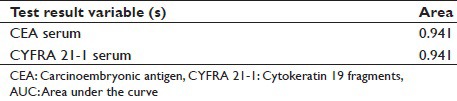

The performance of each marker at various levels of specificity was analyzed by comparing AUC ROC. The area under curve of pleural fluid CEA (0.942) is more than area under curve of serum CEA (0.941), serum CYFRA 21-1 (0.941), and pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 (0.930) [Table 2].

Table 2.

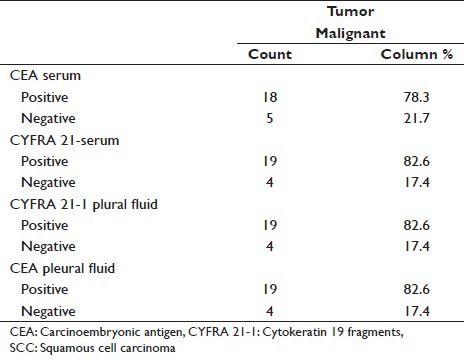

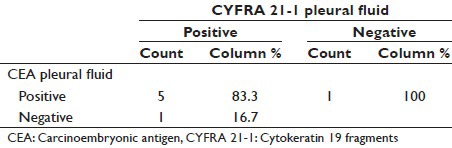

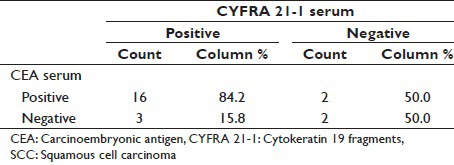

Tumor marker sensitivity in SCC

Serum CEA has sensitivity of 78.3% for SCC as compared to serum CYFRA 21-1 which has sensitivity of 82.6%. Pleura fluid CEA has sensitivity of 82.6% for SCC which is similar to Pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 which has sensitivity of 82.6% [Table 3].

Table 3.

AUC

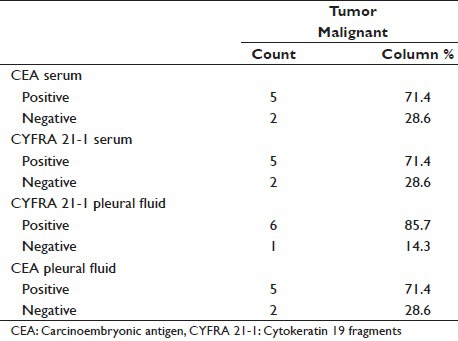

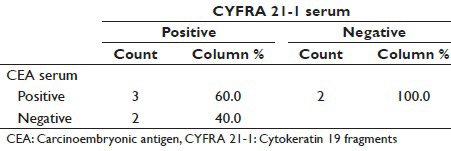

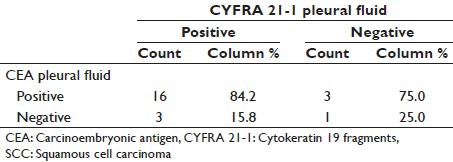

Serum CEA has sensitivity of 71.4% for Adenocarcinoma, which is similar to serum CYFRA 21-1, which has sensitivity of 7 1.4%. Pleural fluid CEA has sensitivity of 71.4% for Adenocarcinoma as compared to pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1, which has sensitivity of 85.7% [Table 4].

Table 4.

Tumor marker sensitivity in adenocarcinoma

Pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 positivity was observed among 6 adenocarcinoma subjects 85.7%, of which pleural fluid CEA who exhibited positivity among 5 (83.3%) subjects.

DISCUSSION

In malignant effusion, the cytologic examination is important because of its less invasiveness and ease. However, we sometimes encounter highly suspected cases of malignant effusion with repeated negative cytology findings. A pleural needle biopsy adds little to cytology, and thus an aggressive diagnostic technique such as thoracoscopy or thoracotomy should be considered.[5] The evaluation of tumor markers in serum and pleural fluid has been proposed as an alternative way of establishing a diagnosis of MPE. Therefore, we evaluated the diagnostic utility of two tumor markers CEA and CYFRA 21-1 for lung cancer to differentiate malignant from benign effusion.

The current study is an attempt to add to the already existing data regarding diagnostic utility of two tumor markers CEA and CYFRA 21-1 for lung cancer to differentiate malignant from benign effusion.

In the present study, we compared serum and pleural fluid levels of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in nonsmall cell carcinoma with MPE and tubercular effusion. The marker levels were much lower in tubercular effusion as compared with malignant effusion. The cut-off level for CEA in serum as provided in our kit in nonsmokers is 5.0 ng/ml and in smokers is 6.5 ng/ml. The cut-off level for CEA in pleural fluid in our study was fixed at 4.8 ng/ml. The cut-off level for CYTRA 21-1 in serum as provided in our kit in nonsmokers and in smokers is 3.3 ng/ml. The cut-off level for CYFRA 21-l in pleural fluid in our study was fixed at 21.6 ng/ml (cut-off was calculated by means of control +1SD).

The most common method of reaching at diagnosis in our cases was CT guided biopsy 16 cases (53.4%) as compared to bronchoscopy 14 cases (46.6%), which did not correlate with results shown by Buccheri et al.[10] as 53% cases being diagnosed by bronchoscopy. The discordance in our data could be due to small number of patients studied in our study.

Cytokeratin 19 fragment levels in serum and pleural fluid

In cases, serum CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 34.1 ± 29.9 ng/ml with a range of 1.6–128.3, whereas in controls serum, CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 1.9 ± 1.0 ng/ml with a range of 0.5–4.7 [Table 1].

In cases, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 160.1 ± 177.1 ng/ml with a range of 5.4–517.2, whereas in controls, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 15.9 ± 5.7 ng/ml with range of 7.2–29.6 [Table 1].

When compared with study conducted by Lee et al., in cases, serum CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 14.6 ± 33.3 ng/ml, whereas in controls, serum CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 0 ng/ml. In cases, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 61.7 ± 50.6 ng/ml, whereas in controls, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels had mean value of 23.2 ± 23 ng/ml.

In SQC, mean serum CYFRA 21-1 levels were 33.9 ng/ml with a SD of 25.5 when compared with study conducted by Lee et al.,[8] in SQC mean serum CYFRA 21-1 levels were 19.2 ng/ml with a SD of 18.3 [Table 5].

Table 5.

Tumor markers with mean±SD

In ACL, mean serum CYFRA 21-1 levels were 34.7 ng/ml with SD of 44.1. When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.,[8] ACL mean serum CYFRA 21-1 levels were 14.4 ng/ml with a SD of 38.7 [Table 5].

In SQC, mean pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels were 157.9 ng/ml with SD of 166.4. When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.,[8] SQC mean pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels were 94.3 ng/ml with a SD of 56.5 [Table 5].

In ACL, mean pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels were 167.5 ng/ml with a SD of 223.4. When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.,[8] ACL mean pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 levels were 60.3 ng/ml with a SD of 50.2 [Table 5].

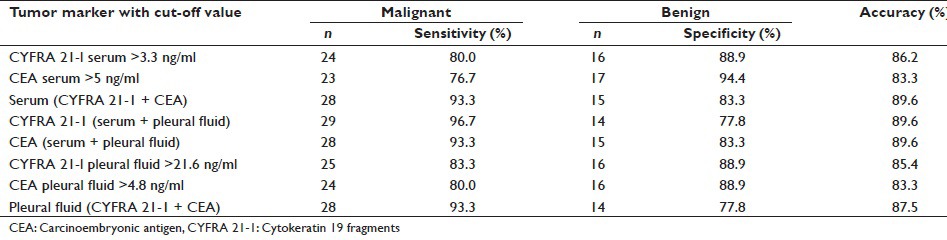

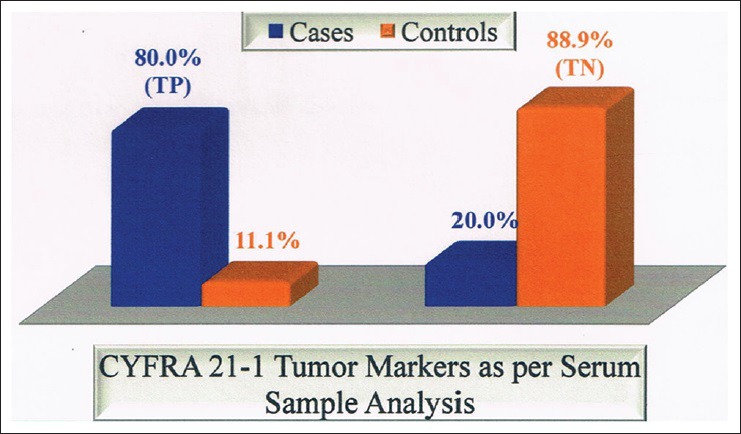

In our study, serum CYFRA 21-1 had a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 88.9%, and accuracy of 86.2% [Table 6, Figure 1]. while as Lee et al.,[8] Dejsomritrutai et al.[24] and Wagner et al.,[31] observed sensitivity of 45.2%, 81.5%, and 71.4%, and specificity of 100%, 97%, and 93%, respectively.

Table 6.

Tumor markers with sensitivity, specificity and accuracy pattern with cut-off value

Figure 1.

Cytokeratin 19 fragment tumor marker as per serum sample analysis. TP: True positives, TN: True negatives

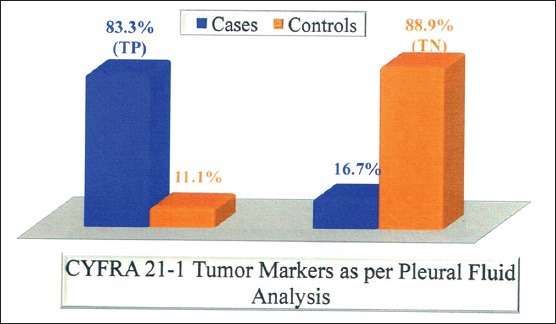

In our study, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 had a sensitivity of 83.3%, specificity of 88.9%, and accuracy of 85.4%. Various studies used cut-off values of pleural fluid CYFRA [Table 6 and Figure 2] 21-1 ranging from 8 to 175 ng/ml for diagnosis of malignant effusion, we used 21.6 ng/ml, and we obtained sensitivity and specificity 83.3% and 88.9%, respectively, while as other studies had sensitivity and specificity ranging from 22% to 91% and 71.4–100%, respectively [Table 6].

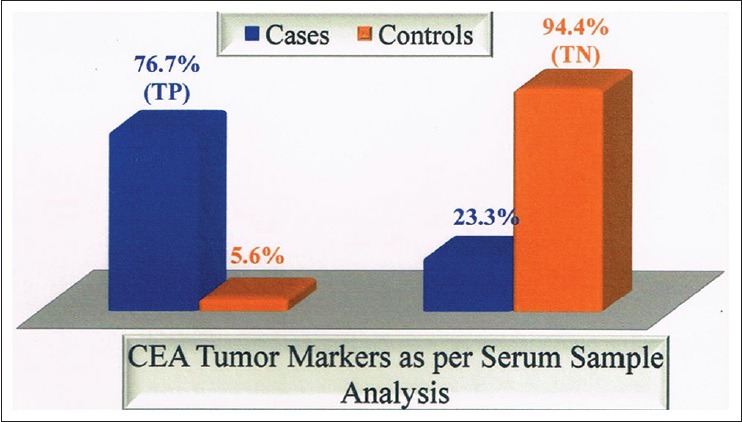

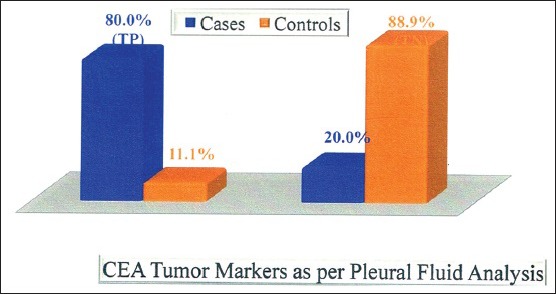

Figure 2.

Carcinoembryonic antigen tumor marker as per serum sample analysis. TP: True positives, TN: True negatives

Carcinoembryonic antigen levels in serum and pleural fluid

In our study, serum CEA levels in cases had mean value of 24.9 ± 47.3 ng/ml with a range of 1–267.9, whereas in controls, serum CEA levels had mean value of 1.9 ± 1.4 ng/ml with a range of 0.2–6.8 [Table 1].

In our study, pleural fluid CEA levels in cases had mean value of 89.8 ± 207.4 ng/ml with a range of 1–861.2, whereas in controls, pleural fluid CEA levels had mean value of 2.5-2.3 ng/ml with a range of 1–8.9 ng/ml [Table 1].

When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.[8] and Pasaoglu et al.,[32] serum CEA levels in cases had mean value of 33.7 ± 54.3 ng/ml and 59.2 ± 129.0 ng/ml, respectively, whereas in controls serum CEA levels had mean value of 2.1 ± 1.7 ng/ml and 1.96 ± 3.6 ng/ml, respectively. Lee et al.[8] and Pasaoglu et al.[32] observed that pleural fluid CEA levels in cases had mean value of 659.5 ± 1314 ng/ml and 124.4 ± 214.3 ng/ml, respectively, whereas in controls, pleural fluid CEA levels had mean value of 1.6 ± 2.1 ng/ml and 1.12 ± 2.7 ng/ml, respectively.

In our study, mean serum CEA levels in SQC were 16-0 ng/ml with a SD of 10.8. When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.[8] mean serum CEA levels in SQC were 19.2 ng/ml with a SD of 18.3.

In our study, mean serum CEA levels in ACL were 54.1 ng/ml with a SD of 95.3. When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.[8] mean serum CEA levels in ACL were 14.4 ng/ml with a SD of 38.7 [Table 5].

In our study, mean pleural fluid CEA levels in SQC were 34.4 ng/ml with a SD of 28.5. When compared with study conducted by Lee et al.[8] mean pleural fluid CEA levels in SQC were 94.3 ng/ml with a SD of 56.5 [Table 5].

In our study, mean pleural fluid CEA levels in ACL were 271.8 ng/ml with a SD of 393.2. W. Tien compared with study conducted by Lee et al.[8] mean pleural fluid CEA levels in ACL were 60.3 ng/ml with SD of 50.2 [Table 6].

We observed Serum CEA had a sensitivity of 76.7%, specificity of 94.4%, and accuracy of 83.3% [Table 6 and Figures 3–6]. Lee et al.,[8] Wagner et al.,[31] and Pasaoglu et al.[32] observed a sensitivity of 67.6%, 57.1%, and 30.5% specificity of 92.9%, 100% and accuracy of 75%, 93%, and 73%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Carcinoembryonic antigen tumor marker as per pleural fluid analysis

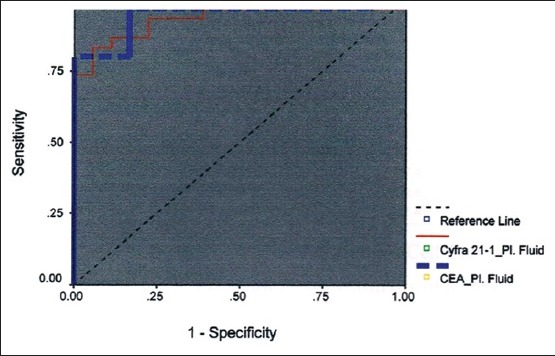

Figure 6.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and cytokeratin 19 fragments

Figure 4.

Cytokeratin 19 fragment tumor marker as per pleural fluid analysis

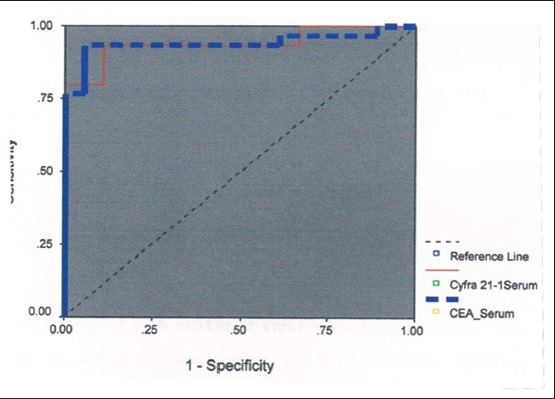

Figure 5.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for serum carcinoembryonic antigen and cytokeratin 19 fragments

We observed pleural fluid CEA had a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 88.9%, and accuracy of 83.3% [Table 6 and Figure 1]. Various studies used cut-off values of pleural fluid CEA ranging from 3 to 50 ng/ml for diagnosis of malignant effusion, we used 4.8 ng/ml, and we obtained sensitivity and specificity 80% and 88.9%, respectively, while as other studies had sensitivity and specificity ranging from 31% to 82.4% and 77–100%, respectively.

In our study, pleural fluid CEA has sensitivity of 71.4% for adenocarcinoma [Table 4] as compared to study conducted by Porcel et al.[15] and Salama et al.[21] whose study showed a sensitivity of 59% and 71.2%, respectively. In our study, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 has sensitivity of 85.7% for adenocarcinoma [Table 4] as compared to study conducted by Porcel et al.[15] and Salama et al.,[21] whose study showed a sensitivity of 22% and 59%, respectively.

In our study, pleural fluid CEA has sensitivity of 82.6% for SCC [Tables 3–11]. as compared to study conducted by Porcel et al.[15] and Salama et al.,[21] whose study showed a sensitivity of 18% and 100%, respectively.

Table 11.

Comparison of pleural fluid CEA and pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 in adenocarcinoma

Table 7.

AUC

Table 8.

Comparison of serum CEA and serum CYFRA 21-1 in SCC

Table 9.

Comparison of serum CEA and serum CYFRA 21-1 in adenocarcinoma

Table 10.

Comparison of pleural fluid CEA and pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 in SCC

In our study, pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 has sensitivity of 82.6% for SCC as compared to study conducted by Porcel et al.[15] and Salama et al.,[21] whose study showed a sensitivity of 9% and 75%, respectively. Porcel et al.[15] observed less sensitivity as he has also studied probable (cytology negative for malignant cells) MPE.

By study of combination of tumor markers, we found that CYFRA 21-1 (serum + pleural fluid) has sensitivity of 96.7%, highest of any combination and specificity of 77.8%, while as Lee et al.[8] and Dejsomritrutai et al.[25] observed sensitivity of 70%, 88.9%, respectively, and Lee et al.[8] observed specificity of 81.8% [Table 6].

In our study, we observed that CEA (serum + pleural fluid) has sensitivity of 93.3%, and specificity of 83.3%, while as Lee et al.[8] observed sensitivity of 85.3% and specificity of 83.3% [Table 6].

In our study, we observed that serum (CYFRA 21-1 + CEA) and pleural Fluid (CYFRA 21-1 + CEA) has sensitivity and specificity of 93.3%, 93.3%, 83.3%, and 77.8%, respectively, while as sensitivity and specificity of 77.4%, 90.9%, 100%, and 75% were observed by Lee et al.[8] [Table 6].

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Vast number of data is emerging for the use of serum and pleural fluid CYFRA 21-1 and CEA levels as a markers for the diagnosis of MPE in lung cancer

CYFRA 21-1 (serum-pleural fluid) is a sensitive marker for NSCLC with sensitivity of 96.7%, highest of any combination (serum [CYFRA 21-1 − CEA] CEA [serum + pleural fluid], pleural fluid [CYFRA 21-1 + CEA]), and specificity of 77.8%

Levels of CYFRA 21-l (serum + pleural fluid) are increased in MPE, so it is better to be used in suspicious MPE showing negative cytology, particularly in the absence of a visible tumor and or unsuitability for invasive procedure

Determination of tumor markers (CEA and CYFRA 21-1) in the pleural fluid may be helpful as a complimentary tool for diagnosis of pleural effusion.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS PROFILE

Sushil Sharma: Senior Resident Medicine MD, Department of Medicine, GMC and Hospital, Jammu, J & K, India

Sanjay Bhat: Consultant, Department of Medicine, ASCOMS and Hospital, Jammu, J & K, India

Vikas Chandel: Senior Resident MD, Department of Medicine , ASCOMS and Hospital, Jammu, J&K, India

Mayank Sharma: Senior Resident MD, Department of Medicine , ASCOMS and Hospital, Jammu, J&K, India

Pulkit Sharma: Intern MBBS, ASCOMS and Hospital, Jammu, J&K, India

Sakul Gupta: Senior Resident MD, Department of Medicine , ASCOMS and Hospital, Jammu, J&K, India

Sashank Sharma: Postgraduate MD, Department of Medicine , ASCOMS and Hospital, Jammu, J&K, India

Aijaz Ahmed Bhat: Postgraduate MD, Department of Medicine , ASCOMS & Hospital, Jammu, J&K, India

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernard Stewart, Christopher P. Wild World Cancer Report. 2014;(Ch. 1.1) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan NA, Afroz F, Lone MM, Teli MA, Muzaffar M, Jan N. Profile of lung cancer in Kashmir, India: A five-year study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:187–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marel M, Stastny B, Melínová L, Svandová E, Light RW. Diagnosis of pleural effusions. Experience with clinical studies, 1986 to 1990. Chest. 1995;107:1598–603. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.6.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenton KN, Richardson JD. Diagnosis and management of malignant pleural effusions. Am J Surg. 1995;170:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulanger E, Gérard L, Gabarre J, Molina JM, Rapp C, Abino JF, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of human herpesvirus 8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in patients with AIDS. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4372–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das DK. Serous effusions in malignant lymphomas: A review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:335–47. doi: 10.1002/dc.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Chang JH. Diagnostic utility of serum and pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen, neuron-specific enolase, and cytokeratin 19 fragments in patients with effusions from primary lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:2298–303. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pamies RJ, Crawford DR. Tumor markers. An update. Med Clin North Am. 1996;80:185–99. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buccheri G, Torchio P, Ferrigno D. Clinical equivalence of two cytokeratin markers in mon-small cell lung cancer: A study of tissue polypeptide antigen and cytokeratin 19 fragments. Chest. 2003;124:622–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.2.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, Rot MK, Oostendorp T, Huysmans A, van Muijen GN, et al. Cytokeratins in different types of human lung cancer as monitored by chain-specific monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3221–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zissimopoulos A, Stellos K, Permenopoulou V, Petrakis G, Theodorakopoulos P, Baziotis N, et al. The importance of the tumor marker CYFRA 21-1 in patients with lung cancer after surgery or chemotherapy. Hell J Nucl Med. 2007;10:62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rastel D, Ramaioli A, Cornillie F, Thirion B. CYFRA 21-1, a sensitive and specific new tumour marker for squamous cell lung cancer. Report of the first European multicentre evaluation. CYFRA - Multicentre Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:601–6. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Light RW, editor. Pleural Diseases. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001. Pleural effusions related to metastatic malignancies; pp. 108–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porcel JM, Vives M, Esquerda A, Salud A, Pérez B, Rodríguez-Panadero F. Use of a panel of tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 15-3, and cytokeratin 19 fragments) in pleural fluid for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant effusions. Chest. 2004;126:1757–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pettersson T, Klockars M, Fröseth B. Neuron-specific enolase in the diagnosis of small-cell lung cancer with pleural effusion: A negative report. Eur Respir J. 1988;1:698–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimokata K, Niwa Y, Yamamoto M, Sasou H, Morishita M. Pleural fluid neuron-specific enolase. A useful diagnostic marker for small cell lung cancer pleurisy. Chest. 1989;95:602–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.San Jose ME, Alvarez D, Valdes L, Sarandeses A, Valle JM, Penela P. Utility of tumour markers in the diagnosis of neoplastic pleural effusion. Clin Chim Acta. 1997;265:193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(97)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miédougé M, Rouzaud P, Salama G, Pujazon MC, Vincent C, Mauduyt MA, et al. Evaluation of seven tumour markers in pleural fluid for the diagnosis of malignant effusions. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:1059–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero S, Fernández C, Arriero JM, Espasa A, Candela A, Martín C, et al. CEA, CA 15-3 and CYFRA 21-1 in serum and pleural fluid of patients with pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:17–23. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salama G, Miédougé M, Rouzaud P, Mauduyt MA, Pujazon MC, Vincent C, et al. Evaluation of pleural CYFRA 21-1 and carcinoembryonic antigen in the diagnosis of malignant pleural effusions. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:472–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh H, Sumi M, Yagyu H, Ishikawa H, Suyama T, Naitoh T, et al. Clinical evaluation of CYFRA 21-1 in malignant pleural fluids. Oncology. 1995;52:211–4. doi: 10.1159/000227459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toumbis M, Rasidakis A, Passalidou E, Kalomenidis J, Alchanatis M, Orphanidou D, et al. Evaluation of CYFRA 21-1 in malignant and benign pleural effusions. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YC, Knox BS, Garrett JE. Use of cytokeratin fragments 19.1 and 19.21 (Cyfra 21-1) in the differentiation of malignant and benign pleural effusions. Aust N Z J Med. 1999;29:765–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1999.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dejsomritrutai W, Senawong S, Promkiamon B. Diagnostic utility of CYFRA 21-1 in malignant pleural effusion. Respirology. 2001;6:213–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang MS, Jong SB, Tsai MS, Lin MS, Chong IW, Lin HC, Hwang JJ. Comparison of cytokeratin fragment 19 (CYFRA 21-1), tissue polypeptide antigen (TPA) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumour markers in bronchogenic carcinoma. Respiratory Medicine. 1997;91:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeda Y, Segawa Y, Takigawa N, Takata I, Fujimoto N. Clinical usefulness of serum cytokeratin 19 fragment as a tumor marker for lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:764–71. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.35.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibayama T, Ueoka H, Tabata M, Nishi K, Kiura K, Gemba K, et al. Diagnostic Utility of CYFRA21-1, ProGRP and CEA in Lung Cancer. ASCO Annual Meeting. 1996 Abstract No. 1155. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupey J, Wilson T, Freedman SO, Gold P. The preparation of purified carcinoembryonic antigen of the human digestive system from large quantities of tumor tissue. Immunochemistry. 1972;9:617–22. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(72)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansour EG, Hastert M, Park CH, Koehle KA. Tissue and plasma carcinoembryonic antigen in early breast cancer a prognostic factor. Cancer. 1983;51:1243–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830401)51:7<1243::aid-cncr2820510712>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beckles MA, Spiro SG, Colice GL, Rudd RM. American College of Chest Physicians. The physiologic evaluation of patients with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):105S–14S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.105s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner IC, Guimarães MJ, da Silva LK, de Melo FM, Muniz MT. Evaluation of serum and pleural levels of the tumor markers CEA, CYFRA21-1 and CA 15-3 in patients with pleural effusion. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33:185–91. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132007000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasaoglu G, Zamani A, Can G, Oktay Ý. Diagnostic value of CEA, CA-19-9, CA 125 and CA 15-3 levels in malignant pleural fluids. Eur J Gen Med. 2007;4:165–71. [Google Scholar]