Abstract

Background:

While many studies have previously focused on fingolimod's effect on immune cells, the effect it has on circulating and local central nervous system platelets (Plts) has not yet been investigated. This study will elucidate what effects fingolimod treatment has on multiple sclerosis (MS) patients’ plasma Plt levels. In addition, it will propose possible reasoning for these effects and suggest further investigation into this topic.

Methods:

This quasi-experimental study used patients from the Isfahan Multiple Sclerosis Society to produce a subject pool of 80 patients, including 14 patients who ceased fingolimod use due to complications. The patients had their blood analyzed to determine Plt levels both 1-month prior to fingolimod treatment and 1-month after fingolimod treatment had been started.

Results:

The mean level of Plts before initiation of fingolimod therapy (Plt1) among these MS patients was 256.53 ± 66.26. After 1-month of fingolimod treatment, the Plt level yielded an average of 229.96 ± 49.67 (Plt2). This number is significantly lower than the average Plt count before treatment (P < 0.01).

Conclusions:

MS patients taking oral fingolimod treatment may be at risk for side-effects caused by low Plt levels. This may not be a factor for patients with higher or normal Plt levels. However, a patient with naturally low Plt levels may experience a drop below the normal level and be at risk for excessive bleeding. In addition to these possible harmful side-effects, the decreased Plt population may pose positive effects for MS patients.

Keywords: Fingolimod, multiple sclerosis, platelet

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes deterioration of the myelin sheath leading to a myriad of neurological symptoms. Both physical and cognitive symptoms are frequently observed in MS patients. The disease can lead to increasing levels of disability. There is still no understanding of what causes MS or a cure for the disease. Fingolimod is an immunomodulatory drug that has recently been approved for the treatment of MS. It was the first oral medication approved for the treatment of MS, most notably for relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). Other drugs that are injectable or given intravenously can be ineffective in RRMS. It is the first sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator to be approved as a medication for any disease.[1] Sphingolipids are a class of signaling molecules that are most densely expressed in the brain.[2] Fingolimod acts by agonizing the S1P1 receptor and producing a subsequent down-regulation of the receptor's expression.[3] S1P1 functions by allowing lymphocytes to leave the lymphoid tissues and enter the circulation. When fingolimod is used, this function is interrupted thereby preventing some lymphocytes from entering the central nervous system (CNS).[4,5] Fingolimod also has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which allows it to directly affect the CNS.[6] The most exciting aspect of fingolimod may not be in its action but in its mode of administration. There are currently only three oral medications on the market for treating MS, including fingolimod. All other MS treatments involve either intravenous administration or subcutaneous injection. Patient compliance for oral drugs is much higher than more invasive ones.[7]

Fingolimod has shown promising results so far. The drug has been able to produce remission in patients with severe RRMS and some cases ease of nonremitting forms of MS.[8,9,10,11] Fingolimod, like most drugs, is not without risk. The most serious include heart conditions such as atrioventricular block and symptomatic bradycardia. These cardiovascular effects are most likely caused by the down-regulation of S1P1 receptor function fingolimod causes. Sphingolipids have been indicated as cardiovascular protectants that promote a regular heart rate.[12] In rare cases is can also cause severe herpetical viral infections and macular edema.[11,13,14,15] Cardiovascular side-effects may be more common in patient populations than suggested by clinical trials.[16] In a Phase III trial, one woman died who did not have varicella-zoster virus (VZV) antibodies due to a lack of being immunized or previously having the chickenpox. When she contracted a primary infection while on fingolimod the results were deadly.[1] In certain rare cases, patients on fingolimod developed aggressive skin cancer after the drug suppressed their immune function.[17] The increased risk for skin cancer is also common with other immunomodulating MS therapies. The most common side-effects include fatigue, headache, back pain, diarrhea, and flu-like symptoms.[10]

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that will investigate the effect fingolimod administration has on a patient's platelet (Plt) count. There have been many studies on fingolimod's effect on lymphocyte populations. Most studies, both experimental and observational, cite fingolimod's ability to produce lymphopenia, or a low lymphocyte count.[18,19] In vitro, fingolimod increased populations of regulatory T cell populations, further supporting the claim that the drug actively suppresses immune function.[20] These results are controversial. There have also been studies citing a decrease in these regulatory T cells after application of fingolimod, or no significant change.[21,22] Investigating the effect fingolimod has on Plt count in the MS population is important to deduce what health risks the drug poses for long-term usage.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This quasi-experimental study was performed on 80 patients who were diagnosed with definite MS (15 men and 65 women). All participants were Iranian and residing in the Isfahan province. The study population of this investigation was selected from the Isfahan Multiple Sclerosis Society (IMSS), the only referral system in Isfahan. All individuals were given definite diagnoses of MS from neurologists using McDonald's criteria. The severity of the patient's disability was assessed using the Expanded Disability Status Scale. Other clinical characteristics and paraclinical features were obtained using patient recall, the IMSS, and taking patient histories. In addition to giving an explanation about the study, written informed consent was obtained from all MS patients who were included in the study before initiation of the study procedure. The Ethnical Institutional Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences also approved this study's protocol.

Procedures

Before initiating fingolimod treatment of the MS patients, 3 ml of venous blood were collected from all subjects using routine venipuncture method and was stored in tubes containing EDTA as an anticoagulant. Since the time of blood sampling (day or night) and physical activity can considerably affect the individual level of Plts, all blood samples were collected in the morning without previous physical activity. The Plt counts were determined using an automated cell counter within 24 h after collection. The cell count was done at the immunology laboratory of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Fingolimod can only be given to patients who have antibodies against the VZV. Patients who have never had the chickenpox and never received the varicella vaccine were immunized with it 1-month prior to starting fingolimod therapy. In order to ensure that the antibodies for VZV were present in the patient's blood, serology testing for varicella immunoglobulin G was done. After the first blood sampling, fingolimod treatment was immediately initiated. One month after beginning fingolimod therapy, all cases were called back to the IMSS and 3 ml blood samples were again obtained. The Plt counts were determined in the same manner as mentioned above. Again, other clinical features and paraclinical characteristics were obtained using a questionnaire required of all participants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for hardware (version 20, IBM, Chicago, IL). Our data were normal according to Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Furthermore, paired sample t-test and independent sample t-test was used for other statistical analysis. All tests were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered as a significant threshold.

RESULTS

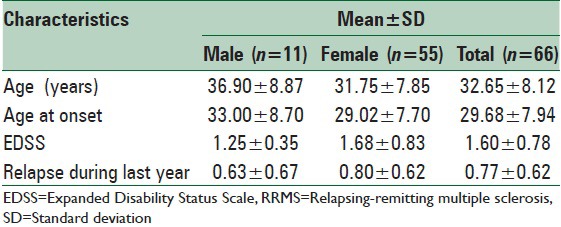

A total of 80 MS patients (15 men and 65 women) with a mean age of 32.65 ± 8.12 and the average age at onset of 29.68 ± 7.94 were enrolled in this study. However, during the study 14 of them were excluded due to treatment-related complications, including cardiovascular, hepatic, gastrointestinal, hematologic, and dermatologic complications. The most frequent complications reported were cardiovascular and skin problems. All of the patients were diagnosed as cases of RRMS according to the McDonald's criteria. Table 1 summarizes other general characteristics and clinical features of the studied patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and paraclinical features of RRMS patients

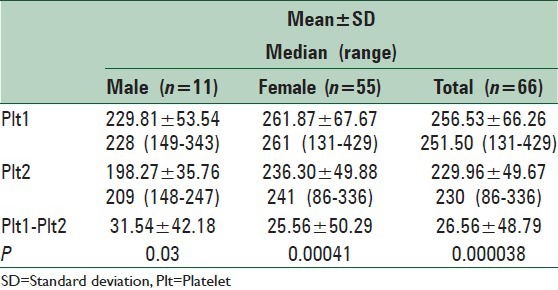

The mean level of Plts before initiation of fingolimod therapy (Plt1) among these MS patients was 256.53 ± 66.26. After 1-month of fingolimod treatment the Plt level yielded an average of 229.96 ± 49.67 (Plt2). This number is significantly lower than the average Plt count before treatment (P < 0.01). Before initiation of treatment, the average Plt counts for men and women were 229.81 ± 53.54 and 261.87 ± 67.67, respectively. After 1-month of follow-up the level of Plt reached 198.27 ± 35.76 and 236.30 ± 49.88 among men and women respectively. This shows a statistically significantly decreased level of Plts circulating in both men and women. This reduction was more considerable among women (P = 0.03 in men, P < 0.01 in women) [Table 2]. Our data showed that the vast of majority of the cases had decreased Plt count after 1-month of treatment with fingolimod.

Table 2.

Plt count before and after treatment with fingolimod

Prior to the treatment, there was no significant difference between women and men relating to their Plt count (P = 0.14), whereas after 1-month of beginning of the treatment, the Plt count of women was significantly higher than that of men (P = 0.01).

We did not have any patients, whose Plt count dropped below the reference limit.

DISCUSSION

Our results show a statistically significant decrease in Plt levels for patients taking fingolimod oral medication for 1-month. Plt counts were decreased in the entire cohort and in both males and females separately. The reduction in Plt count for women was more significant than that for men. Although these average levels did not drop below the “normal” range for adults, it should be noted that these levels are after only a month of treatment. Further investigation will need to be done to determine what the long-term effects are taking fingolimod. While we do not have any other references to compare these results to, we do have a vast expanse of knowledge about the health risks fingolimod treatment poses. There is a significant lack of knowledge about what the long-term effects of taking fingolimod might be for different patient profiles.[23] Another concern is how cessation of fingolimod treatment affects the course of MS progression.[24] There is a dose-dependent relationship between fingolimod and adverse reactions to the drug. Most severely, fingolimod users experience herpes zoster infections and cardiovascular effects including bradycardia.[25]

In an interesting study, Ocwieja et al.[26] have investigated Plt function in healthy volunteers taking fingolimod. They found that the treatment had no significant effect on Plt function.

Besides the obvious health risks a continually decreasing Plt count suggests such as an increased risk of bleeding, this information is crucial to understanding the function of sphingosine receptor for S1P.[27] A decreased level of blood plasma S1P has been demonstrated after the myocardial infraction in rats. This same study found a sharp decrease of S1P in Plts after myocardial infraction.[28] Aspirin is an anti-Plt drug that is often given to patients who have experienced negative cerebrovascular events. While a low-dose of aspirin might produce increased levels of S1P in the blood plasma, a higher dose can cause lowered levels of circulating S1P.[29] If patients are experiencing cardiovascular symptoms from taking the drug, aspirin may be an option for treatment that could interfere with fingolimod's effectiveness.

The decrease in Plt count in these patients, however, may be a positive force for protecting against MS. Plts have recently been identified as a mechanism used in neuroinflammation.[30] Recent studies suggest Plts as a sort of neuroinflammatory instigator that uses a compromised BBB to recruit and activate immune pro-inflammatory cells.[31] In the mouse model for MS, experimental autoimmune encephalitis and in humans, Plts were found in brain lesions suggesting this critical role Plts have in neuroinflammation.[32] This is a new and controversial idea. However, it suggests that fingolimod's effects may not be completely reliant on reducing classic autoimmune cells, such as lymphocytes. The reduction in Plt count may be the reason for fingolimod's success. If so, this suggests that further treatments for autoimmune diseases such as MS could rely only on lowering Plt counts to produce minimal side-effects for maximum gain. By avoiding the targeting of lymphocytes, many extreme side-effects such as rampant skin cancer and herpetical infections might be avoided. Although Ocwieja et al., has earlier investigated the role of fingolimod in Plt count, there is not many evidence with regard to the possible mechanisms that may have impact on the Plt count and function, therefore, decreased Plt count after fingolimod therapy that has been found in our study can show importance of investigating possible underlying mechanisms in future studies. The role Plts have in MS and in fingolimod treatment needs to be further investigated in humans in order to elucidate these further treatment options.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results show a sharp decrease in Plt counts following fingolimod treatment. This is an area that has not been investigated previously in regards to fingolimod's possible long-term effects on patient health. The decrease did not produce an average patient level below health normal levels. However, this study was only done 1-month after fingolimod treatment was initiated and as a limitation had no control group. Further analysis of long-term users will need to be done in order to investigate how drastic the Plt depletion is. Our results also suggest that fingolimod's effectiveness may lie in its ability to reduce Plts in MS patients. This is an important step forward in treatment options for MS and other autoimmune diseases. If Plts can be directly indicated in autoimmune pathogenesis, then perhaps they can be used as a primary target in treating these diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate patients participating in this study. This study was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. We acknowledge the technical help of Hamidreza Jahanbani-Ardakani. The protocol of the study was approved by Kashan University of Medical Sciences with project number of 89-124.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer BA. Initiating oral fingolimod treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6:269–75. doi: 10.1177/1756285613491520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huwiler A, Kolter T, Pfeilschifter J, Sandhoff K. Physiology and pathophysiology of sphingolipid metabolism and signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1485:63–99. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunkhorst R, Vutukuri R, Pfeilschifter W. Fingolimod for the treatment of neurological diseases-state of play and future perspectives. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:283. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun J, Hartung HP. Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181cbf825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann V, Pinschewer D, Chiba K, Feng L. FTY720: A novel transplantation drug that modulates lymphocyte traffic rather than activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anthony DC, Sibson NR, Losey P, Meier DP, Leppert D. Investigation of immune and CNS-mediated effects of fingolimod in the focal delayed-type hypersensitivity multiple sclerosis model. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasperini C, Ruggieri S. Development of oral agent in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: How the first available oral therapy, fingolimod will change therapeutic paradigm approach. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:175–86. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S8927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muris AH, Rolf L, Damoiseaux J, Koeman E, Hupperts R. Fingolimod in active multiple sclerosis: An impressive decrease in Gd-enhancing lesions. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:164. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0164-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen PS. Effects of fingolimod in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:526–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabresi PA, Radue EW, Goodin D, Jeffery D, Rammohan KW, Reder AT, et al. Safety and efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (FREEDOMS II): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:545–56. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, Hartung HP, Khatri BO, Montalban X, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:402–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkmann V, Billich A, Baumruker T, Heining P, Schmouder R, Francis G, et al. Fingolimod (FTY720): Discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:883–97. doi: 10.1038/nrd3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward MD, Jones DE, Goldman MD. Overview and safety of fingolimod hydrochloride use in patients with multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:989–98. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.920820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratchford JN, Costello K, Reich DS, Calabresi PA. Varicella-zoster virus encephalitis and vasculopathy in a patient treated with fingolimod. Neurology. 2012;79:2002–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182735d00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross CM, Baumgartner A, Rauer S, Stich O. Multiple sclerosis rebound following herpes zoster infection and suspension of fingolimod. Neurology. 2012;79:2006–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182735d24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fragoso YD, Arruda CC, Arruda WO, Brooks JB, Damasceno A, Damasceno CA, et al. The real-life experience with cardiovascular complications in the first dose of fingolimod for multiple sclerosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:712–4. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato DK, Callegaro D. Oral fingolimod to treat multiple sclerosis: See your cardiologist first. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:651–2. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20140171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarrasón G, Aulí M, Mustafa S, Dolgachev V, Domènech MT, Prats N, et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 antagonist, W146, causes early and short-lasting peripheral blood lymphopenia in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:1773–9. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson TA, Evans BL, Durafourt BA, Blain M, Lapierre Y, Bar-Or A, et al. Reduction of the peripheral blood CD56(bright) NK lymphocyte subset in FTY720-treated multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol. 2011;187:570–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou PJ, Wang H, Shi GH, Wang XH, Shen ZJ, Xu D. Immunomodulatory drug FTY720 induces regulatory CD4() CD25() T cells in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:40–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Tan W, Guo D, He S. Reduction of CD4 positive T cells and improvement of pathological changes of collagen-induced arthritis by FTY720. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;573:230–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaudel CP, Frink M, Schmiddem U, Probst C, Bergmann S, Krettek C, et al. FTY720 for treatment of ischemia-reperfusion injury following complete renal ischemia; impact on long-term survival and T-lymphocyte tissue infiltration. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sørensen PS. Balancing the benefits and risks of disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;311(Suppl 1):S29–34. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(11)70006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellmann MA, Lev N, Lotan I, Mosberg-Galili R, Inbar E, Luckman J, et al. Tumefactive demyelination and a malignant course in an MS patient during and following fingolimod therapy. J Neurol Sci. 2014;344:193–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonagh M. Drug Class Review: Disease-Modifying Drugs for Multiple Sclerosis: Single Drug Addendum: Fingolimod: Final Original Report. Portland (OR) 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ocwieja M, Meiser K, David OJ, Valencia J, Wagner F, Schreiber SJ, et al. Effect of fingolimod (FTY720) on cerebral blood flow, platelet function and macular thickness in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:1354–65. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregg D, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Cardiology patient page. Platelets and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;108:e88–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086897.15588.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knapp M, Zendzian-Piotrowska M, Blachnio-Zabielska A, Zabielski P, Kurek K, Górski J. Myocardial infarction differentially alters sphingolipid levels in plasma, erythrocytes and platelets of the rat. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:294. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knapp M, Lisowska A, Knapp P, Baranowski M. Dose-dependent effect of aspirin on the level of sphingolipids in human blood. Adv Med Sci. 2013;58:274–81. doi: 10.2478/ams-2013-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sotnikov I, Veremeyko T, Starossom SC, Barteneva N, Weiner HL, Ponomarev ED. Platelets recognize brain-specific glycolipid structures, respond to neurovascular damage and promote neuroinflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer HF, Chavakis T. Platelets and neurovascular inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:888–93. doi: 10.1160/TH13-02-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langer HF, Choi EY, Zhou H, Schleicher R, Chung KJ, Tang Z, et al. Platelets contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Circ Res. 2012;110:1202–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]