Abstract

Background

Reproductive traits such as number of stillborn piglets (SB) and number of teats (NT) have been evaluated in many genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Most of these GWAS were performed under the assumption that these traits were normally distributed. However, both SB and NT are discrete (e.g. count) variables. Therefore, it is necessary to test for better fit of other appropriate statistical models based on discrete distributions. In addition, although many GWAS have been performed, the biological meaning of the identified candidate genes, as well as their functional relationships still need to be better understood. Here, we performed and tested a Bayesian treatment of a GWAS model assuming a Poisson distribution for SB and NT in a commercial pig line. To explore the biological role of the genes that underlie SB and NT and identify the most likely candidate genes, we used the most significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), to collect related genes and generated gene-transcription factor (TF) networks.

Results

Comparisons of the Poisson and Gaussian distributions showed that the Poisson model was appropriate for SB, while the Gaussian was appropriate for NT. The fitted GWAS models indicated 18 and 65 significant SNPs with one and nine quantitative trait locus (QTL) regions within which 18 and 57 related genes were identified for SB and NT, respectively. Based on the related TF, we selected the most representative TF for each trait and constructed a gene-TF network of gene-gene interactions and identified new candidate genes.

Conclusions

Our comparative analyses showed that the Poisson model presented the best fit for SB. Thus, to increase the accuracy of GWAS, counting models should be considered for this kind of trait. We identified multiple candidate genes (e.g. PTP4A2, NPHP1, and CYP24A1 for SB and YLPM1, SYNDIG1L, TGFB3, and VRTN for NT) and TF (e.g. NF-κB and KLF4 for SB and SOX9 and ELF5 for NT), which were consistent with known newborn survival traits (e.g. congenital heart disease in fetuses and kidney diseases and diabetes in the mother) and mammary gland biology (e.g. mammary gland development and body length).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Reproductive traits, such as number of stillborn piglets (SB) and number of teats (NT), are widely included in the selection indices of pig breeding programs due to their importance to the pig industry. The number of SB is a complex trait that is directly affected by the total number of piglets born [1] and by temporal gene effects in different parities [2]. In humans, it has been shown that kidney diseases and diabetes in the mother and congenital heart disease in the fetus are some of the main causes of the occurrence of stillbirths [3–5]. In pigs, however, a better biological understanding of these traits is still needed to improve selection against SB. Number of teats is a trait with a large influence on the mothering ability of sows [6], since it is a limiting factor for increasing the number of weaned piglets. Biologically, the development of embryonic mammary glands requires the coordination of many signaling pathways to direct cell shape changes, cell movements, and cell–cell interactions that are necessary for proper morphogenesis of mammary glands [7]. In addition, number of vertebrae, which determines the body length of the sow, may also have a direct relation with the final NT that is observed in pigs [8].

Since these traits are directly involved with higher production and welfare of piglets, several genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed for SB and NT [2, 9, 10]. However, in these GWAS, these traits were assumed to be normally distributed, which may not be true. Both SB and NT are measured as count variables, and therefore they follow discrete distributions such as the Poisson distribution. Although the Poisson distribution has already been implemented in animal breeding in the context of traditional mixed models [11, 12] and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping [13, 14], there are no reports of GWAS for SB and NT using such models.

Poisson models can be fitted using a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach [15]. By applying Poisson models to GWAS with a traditional mixed animal linear model, it is possible to fit all markers simultaneously by using the genomic relationship matrix [16], as performed in genomic best linear unbiased prediction (GBLUP). GBLUP has been widely used in genome-wide selection (GWS), in which the vector of genome enhanced breeding values (GEBV), from each MCMC iteration, can be directly converted into a vector of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) allele substitution effects [17, 18]. Based on this, samples of the posterior distribution for each SNP effect are generated at each cycle and significance tests based on highest posterior density (HPD) intervals can be performed [19, 20] in order to identify the most relevant SNPs. In addition, the posterior probability (PPN0) of the estimated effect being smaller than 0 (for negative effects) or greater than 0 (for positive effects), as proposed by Ramírez et al. [20] and Cecchinato et al. [21], can also be used to report the significance of SNP effects under a Bayesian approach. Furthermore, when considering all SNPs simultaneously in the model (in this case, the GBLUP assuming a general shrinkage parameter), some issues such as the influence of gene length (i.e. occurrence of bias that favors genes including larger numbers of SNPs) [22] can be partially minimized by estimating the effect of a particular SNP in the presence of all other SNP effects.

Although many GWAS have been performed, the biological meaning of the identified candidate genes, as well as their functional relationship with transcription factors (TF), still need to be better understood. Results of GWAS can be used for the genetic dissection of complex phenotypes by applying a network approach to the identified genes in the genomic regions around significant SNPs. The genes that are linked to significant SNPs can be used to examine the sharing of pathways and functions, as well as the enrichment of significantly related TF in the selected genes. Some studies have shown that TF genes can be associated with important traits in pigs, e.g. PIT1 in carcass traits [23] and SREBF1 in the regulation of muscle fat deposition [24].

Thus, providing evidence for an interaction between a TF gene that is known to be related with a given trait and its predicted target genes via the analysis of regulatory sequences and the construction of gene-TF networks serves as an in silico validation for the gene-gene interactions. A gene-TF network facilitates the identification of the most probable group of candidate genes for the studied trait. In addition, these genes can be used in further functional analyses of in vitro and in vivo validation. Similar approaches have been performed for puberty-related traits in cattle [25, 26] to identify related candidate genes and TF. In pigs, however, this approach has just begun to be exploited [27].

In this study, we performed a Bayesian treatment of a GWAS model assuming Poisson and Gaussian distributions for SB and NT in a commercial pig line. Then, we used the significant SNPs to obtain related genes and generate gene-TF networks, in order to explore the biological roles that underlie the considered traits and identify the most probable candidate genes.

Methods

Phenotypic and genotypic data

Stillbirth records from 1390 Large White (LW) sows with an average of 3.9 parities were evaluated. The average SB number in this population was 1.2, ranging from 0 to 16 SB per litter. NT was counted at birth for 1795 LW animals. The average NT in this population was 15.3, ranging from 14 to 20 teats. All animals were genotyped using the Illumina 60 K + SNP Porcine Beadchip [28]. As a part of quality control procedures, SNPs with a GenCall score less than 0.15 [29], a minor allele frequency less than 0.01, a frequency of missing genotypes greater than 0.05, unmapped SNPs, and SNPs located on the Y chromosome according to the Sscrofa10.2 assembly of the reference genome [30] were excluded from the dataset. After quality control, genotypes of 1657 (NT) and 1200 (SB) animals for 41,647 SNPs were included in the association analyses.

Statistical analyses

Two GBLUP models were fitted to the data under a Bayesian framework. The difference between these models was that one model assumes that the traits follow a Gaussian distribution and the other assumes that the traits follow a Poisson distribution. For the Gaussian response, the following general linear model was assumed:

| 1 |

where y is the vector of phenotypic observations, β is the vector of systematic environmental effects, u is a vector of additive genetic effects, p is a vector of permanent environment effects (fitted only in the model for SB), e is a vector of residual effects, and X, Z, and W are design matrices related to β, u, and p, respectively. Herd-year-season (HYS) was considered as a systematic effect for both SB and NT, while a sow parity number was used only for SB and a sex effect was used only for NT. Sex effects are commonly accounted for when analyzing NT according to Lopes et al. [31], who showed that males had on average 0.35 ± 0.09 more teats than females.

For the Poisson response y, a latent variable (l) was introduced by means of the canonical parameter λ (often called the rate or mean parameter) of the Poisson distribution and the link function on the log scale, i.e., yi ∼ Poi(λ = exp (li)), where exp is the inverse link function. In this case, the linear model presented in (1) can be applied to the latent variable as follows:

| 2 |

Under a traditional Poisson mixed model [32], the conditional mean and variance of observations must be identical but the absence of some explanatory factors and sources of variation may result in a discrepancy (over-dispersion) between these quantities. The extra residual (e) term in Model (2) absorbs all unaccounted sources of variation, while the traditional generalized linear model has no term to which this extra variance can be allocated [33]. Model (2) was initially proposed by Tempelman and Gianola [33], who assumed a gamma distribution for the latent variable in a conjugate conditional distribution from which the parameter estimates were obtained by using a maximum a posteriori method via the Newton–Raphson algorithm. Since the computational simplicity of MCMC methods makes it possible to extend the distributions of the latent variable, we opted for the Gaussian distribution instead of a gamma distribution in order to directly estimate the residual variance, which is defined by functions of the parameters of the gamma distribution under the Tempelman and Gianola [33] approach. Implementation of MCMC algorithms (Gibbs sampler and Metropolis–Hastings) through the conditional posterior distributions for parameters of Model (2), and consequently for Model (1) by replacing l by y, are presented in detail on pages 36 and 37 of Sun et al. [34].

In the Bayesian analysis, the following prior distributions were assumed for the parameters of Models (1) and (2): β ∼ N(0, σ2βl), where σ2β is known and assumed to be large (in this case 1e + 10) in order to represent vague prior knowledge; u ∼ N(0, σ2uG) and p ∼ N(0, σ2pI), with I as an identity matrix and G the genomic relationship matrix (covariances between individuals based on observed similarity at the genomic level) proposed by Van Raden [16]. Thus, where M is the SNP genotype matrix, pi is the allele frequency at SNP i, N is the number of SNPs, and the sum is over all SNPs. This matrix was accessed from the kin function from the synbreed package in R software, which requires the values 0, 1, and 2 for genotypes aa, aA, and AA, respectively.

For the variance components (σ2u, σ2p and σ2e), an inverted Chi squared distribution was considered: σ2u|Vu, and where V (degree of freedom) and S (scale parameter) are hyperparameters. Assuming that where S = Vσ2* and σ2* is the prior most likely value of σ2 [35], the mode of this distribution was equalized to σ2* in order to set the hyperparameter V, i.e. σ2* = VS/(V + 2) = VVσ2*/(V + 2). Thus, we have V2−V−2 = 0, where the roots are V = −1 and V = 2. Since by definition V > 0, we opted for V = 2 and S = Vσ2*, where σ2* was assessed by the variance component estimates from other studies of this same commercial population for SB [36, 37] and NT [31, 38]. To calculate S, the values assumed for , and were, respectively, 0.3575, 0.33 and 3.9125 for SB, and 0.43, 0.0221 and 0.71 for NT.

In both Models (1 and 2), the residual vector was assumed to be , thereby implying a Gaussian likelihood function. In agreement with Hadfield and Nakagawa [15], the conditional probability of the latent variable is proportional to the product of two terms, the Poisson likelihood of the data given l and the Gaussian likelihood based on residual terms, i.e., P(li|y, β, u, p, σ2u, σ2p, σ2e) ∝ ∏Ni=1Pi(yi|li)P(ei|σ2e). Thus, in Model (2), the vector of latent variables (l) was also considered to be an unknown parameter, therefore not allowing for a fully recognizable conditional distribution and requiring the use of the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm to generate samples of posterior distribution for l. For the other unknown parameters , given the closed form of the full conditional posterior distributions, the Gibbs sampler algorithm was used. For the standard linear mixed Model (1) with a Gaussian response and identity link, P(li|y, β, u, p, σ2u, σ2p, σ2e) is always unity, and so the Metropolis–Hastings steps are not required.

Models (1) and (2) were fitted to the data using an adaptation of the MCMCglmm R package [39], with a total of 100,000 iterations, while assuming a burn-in period of 50,000 and a sampling interval (thin) each second iteration. The adaptation involved the use the inverse of the G matrix instead of the inverse of the traditional relationship matrix (A) in the ginverse option of this package.

To evaluate convergence of the MCMC chains, we used the boa.geweke function from the boa (Bayesian Output Analysis) package in the R software. This function enables users to define a matrix in which columns and rows contain the monitored parameters and the MCMC iterations, respectively. The output directly provides the Geweke Z-Scores and associated p values for each one of these parameters, thus allowing for the use of descriptive statistics to make inferences about convergence in the presence of a large number of parameters (marker effects and breeding values), as considered here. Descriptive statistics and histograms for p values from the Geweke test for all parameters, as well as trace plots for the most significant SNPs, are in Additional file 1: Figure S1, Additional file 2: Figure S2, and Additional file 3: Figure S3.

Models (1) and (2) were compared based on the deviance information criterion (DIC) developed by Spiegelhalter et al. [40]: where is a point estimate of the deviance that is obtained by replacing the parameters with their posterior mean estimates in the log-likelihood function, i.e. and respectively, for the Gaussian and Poisson models, and is the effective number of parameters. Models with a smaller DIC are preferred to models with a larger DIC.

One important statistical feature of the present study was the fact that the vector (GEBV) was kept at each kth MCMC iteration () for Models (1) and (2), which enabled us to generate the vector of SNP effects (α) for each iteration using the following linear system: [18], where (MM′)−1 is the generalized inverse and M is the incidence matrix for SNP effects based on the SNP genotypes used in G matrix definition, as previously presented. Once a vector of SNP effects was generated for each iteration (), it was possible to obtain a MCMC chain of 25,000 iterations (see burn-in and thin previously mentioned) for each SNP. Thus, after verifying convergence of these chains by the Geweke and Raftery and Lewis criteria (using, respectively, the functions geweke.diag and raftery.diag of coda R package) [41], a sample of the posterior distribution for the effect of each SNP was obtained. These distributions allowed the calculation of the 95 % HPD (highest posterior density) intervals, as presented by Li et al. [19], and determination of the posterior probability (PPN0) that the SNP effect is greater (for positive effects) or smaller than (for negative effects) zero, as presented by Ramírez et al. [20] and Cecchinato et al. [21]. The HPD intervals and PPN0 were obtained for each SNP and the chromosomal positions of the significant SNPs were used to identify genes that influence the target traits.

Obtaining the SNP effect directly from M′(MM′)−1 and storage of the chains for the effect of each SNP required the use of a large amount of data, which was facilitated by using the Intel Math Kernel Library, which is highly optimized for use on Intel processers and uses a parallel process to decrease computational time. The application of these optimized libraries for matrix computation in genomic issues was discussed in detail in Aguilar et al. [42]. The computer that was used to perform the analyses had 12 cores running Intel(R) Core(™) i7-3930 K CPU @ 3.20 GHz and 96 gb of ram.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between significant SNPs was evaluated using Haploview [43] to identify QTL regions on chromosomes, using the default parameters based on Gabriel et al. [44]. 95 % confidence bounds on D′ [45] were used to determine if a pair of SNPs was in “strong LD”.

Gene-TF networks

Genes that overlapped with significant QTL regions and with individual significant SNPs, along with, for both, a 32.5 kb flanking sequence (half the average distance between SNPs present on the chip), were identified at the dbSNP NCBI web site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). When checking these segments, we identified the presence of any gene that could be related with a QTL or a significant SNP. In addition, studies on the Large White pig breed have demonstrated that even for an average distance between two SNPs of around 200–250 kb, the LD (r2) is still high (0.31), with an average LD greater than 0.2 reported to be necessary for genomic analyses [46, 47]. The identified overlapping genes were then used to obtain functional gene ontology (GO) terms and pathways with GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org/) and TOPPCLUSTER (http://toppcluster.cchmc.org/).

TF enriched in the identified set of genes were found with the TFM-Explorer program (http://bioinfo.lifl.fr/TFM/TFME/). This program uses weight matrices from the JASPAR database [48] to detect all potential TF binding sites (TFBS) from a set of gene sequences and searches for locally overrepresented TFBS. Then, it gives significant clusters (TFBS regions of the input sequences associated with a factor) by calculating a score function with a threshold (p value) equal or greater than 10−3 for each position and each sequence, such as described in Touzet and Varré [49]. The program’s default size for the analyzed promoter region is 2000–200 bp. However, annotations of the genes’ transcription start sites (TSS) are uncertain for some regions in the current assembly, thus to compensate for inaccurate annotated TSS, both in the 5′ and 3′ direction, we increased (no restriction) the limits of the promoter regions, i.e. for the set of genes for each trait, excluding ncRNA genes, we collected 3000 bp upstream and 300 bp downstream sequences (FASTA format) of the genes’ TSS, based on the Sscrofa10.2 assembly at the NCBI web site. This data was then used as input for TFM-explorer and the given list of TF was fed into Cytoscape [50] using a Biological Networks Gene Ontology tool (BiNGO) plugin [51] to identify significantly overrepresented GO terms. Based on overrepresented biological processes in BiNGO and evidence from a review of the literature, we were then able to identify the most representative TF (according to their biological role and literature evidence) that were related to SB and NT to construct a network with gene-TF interactions. With the goal of identifying the most likely candidate genes for the studied traits SB and NT, we applied the Network Analyses Cytoscape tool for number of TFBS and consequently, number of connections in each gene, to determine those that were most strongly connected with SB and NT. Thus, genes with the higher TFBS for the most representative TF were highlighted on the gene-TF network.

Results

Statistical analyses

The convergence diagnostics of MCMC chains for all estimated parameters are summarized in Additional file 1: Figure S1, Additional file 2: Figure S2, and Additional file 3: Figure S3. All MCMC chains achieved the convergence according to Geweke’s test. There was no evidence that allowed us to reject the null hypothesis (stationarity of the MCMC chains) under a significance level of 5 %. This result is illustrated by histograms and descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, minimum and maximum) for the p values from Geweke’s test.

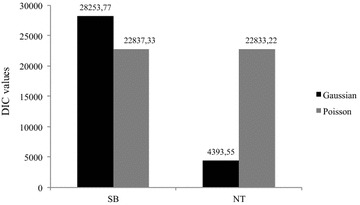

The most appropriate model (Gaussian or Poisson) was determined for each trait (SB and NT) by using DIC (Fig. 1). For SB, the DIC was 5416.44 times smaller with the Poisson model than with the Gaussian model. In contrast, for NT, the Gaussian model had a DIC that was 18439.67 times smaller than with the Poisson model. According to Spiegelhalter et al. [40], models with differences in DIC less than 2 must be equally considered, while models that have DIC that are between 2 and 7 have considerably less support. Thus, by using these differences in DIC as a reference, the Poisson model was clearly superior for SB and the Gaussian was clearly superior for NT. Histograms for the original phenotypes when considering the fit of the Poisson and Gaussian distributions are in Additional file 4: Figure S4. Thus, the remainder of the analyses presented here for SB and NT used the Poisson and Gaussian models, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Deviance information criterion (DIC) plot. DIC values obtained using Gaussian (black) and Poisson (gray) models for stillborn (SB) and number of teats (NT) data

Using these distributions, we identified 18 SNPs related to SB and 65 to NT [see Additional files 5: Table S1, Additional file 6: Table S2, Additional file 7: Figure S5 and Additional file 8: Figure S6]. Significant SNPs were identified based on 95 % HPD intervals and posterior probabilities (PPN0). Under the HPD approach, if zero was not included in the interval for the SNP effect, the SNP was declared as significant. In addition, if the PPN0 value was greater than 0.95, the SNP was also reported as significant.

From the significant SNPs, we identified one QTL region of four SNPs on chromosome 1 for SB and nine QTL regions for NT, with three on chromosome 7 (four, seven, and six significant SNPs in each QTL, respectively), five on chromosome 8 (six, four, five, four, and five significant SNPs in each QTL region, respectively) and one on chromosome 12, with four SNPs [See Additional file 9: Figure S7 and Additional file 10: Figure S8). In addition, 14 significant SNPs were identified for SB and 20 for NT that were not linked to other significant SNPs. Based on these QTL regions plus single SNP locations, we identified 18 and 57 genes that overlapped with significant SNPs, for SB and NT, respectively (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Significant SNPs for stillbirth and associated genes

| SNP | Chr | Position (bp) | QTL | Gene | Distance (bp)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGIS0003207 | 1 | 183,948,686 | – | FEM1B | 14,336 |

| PIAS1 | Inside | ||||

| ITGA11 | 6384 | ||||

| MARC0007670 | 1 | 193,689,396 | – | – | – |

| M1GA0001259 | 1 | 204,647,860 | QTL 1 | SAMD4A | 6863 |

| ALGA0007251 | 1 | 204,871,282 | LOC102168145, WDHD1, SOCS4, MAPK1IP1L, LGALS3 and DLGAP5 | Inside | |

| MARC0056056 | 1 | 204,934,912 | |||

| H3GA0003422 | 1 | 205,020,361 | |||

| ASGA0010665 | 2 | 87,274,373 | – | F2R | 5412 |

| LOC102165085/IQGAP2-like | 30,878 | ||||

| ALGA0014165 | 2 | 87,624,560 | – | LOC100520366 | Inside |

| MARC0000488 | 2 | 87,728,463 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0014249 | 2 | 88,859,718 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0018674 | 3 | 47,957,752 | – | NPHP1 | Inside |

| LOC102166895 | 9013 | ||||

| ASGA0028841 | 6 | 82,315,974 | – | PTP4A2 | 19,505 |

| ASGA0070042 | 15 | 90,388,740 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0086491 | 15 | 111,088,143 | – | LOC100738946/HECW2 | Inside |

| ASGA0070213 | 15 | 111,116,466 | – | LOC100738946/HECW2 | Inside |

| ASGA0072736 | 16 | 26,077,922 | – | – | – |

| H3GA0049633 | 17 | 61,860,123 | – | CYP24A1 | 31,229 |

| ASGA0077857 | 17 | 61,889,054 | – | CYP24A1 | 2298 |

The table shows significant SNPs, their positions in base pairs (bp) on the swine chromosome (Chr), the QTL region, associated genes (genes located in a QTL region or in an interval of 32.5 Kbp around each QTL region or SNP), followed by their distance in base pairs of a single marker or in relation to the first or last SNP of the region

aGene location in relation to the QTL region or to the single SNP

Table 2.

Significant SNPs for number of teats and associated genes

| SNP | Chr | Position (bp) | QTL | Gene | Distance (bp)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALGA0004864 | 1 | 99,713,078 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0012925 | 2 | 34,084,545 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0012930 | 2 | 34,177,927 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0013045 | 2 | 40,181,443 | – | LOC102167107 | 20,750 |

| MARC0055904 | 2 | 40,328,584 | – | SLC17A6 | Inside |

| ASGA0032215 | 7 | 31,600,286 | QTL 1 | KLHL31 | 978 |

| H3GA0020592 | 7 | 31,714,979 | LOC102166539, LOC102166618, GCLC, LOC102167236 and LOC102167364 | Inside | |

| MARC0010879 | 7 | 31,869,398 | |||

| MARC0098266 | 7 | 31,945,954 | KHDRBS2 | 12,332 | |

| ALGA0039995 | 7 | 32,047,280 | QTL 2 | KHDRBS2 | Inside |

| ALGA0040000 | 7 | 32,134,452 | |||

| ASGA0032254 | 7 | 32,166,462 | |||

| ASGA0032255 | 7 | 32,192,051 | |||

| MARC0043689 | 7 | 32,252,888 | |||

| INRA0024655 | 7 | 32,313,430 | |||

| ASGA0032266 | 7 | 32,543,114 | – | – | |

| ALGA0040040 | 7 | 32,915,748 | – | PRIM2 | Inside |

| ASGA0034811 | 7 | 91,149,363 | – | – | – |

| H3GA0022644 | 7 | 102,901,720 | – | PTGR2 | 27,013 |

| MARC0038565 | 7 | 103,495,170 | – | VRTN | 28,094 |

| SYNDIG1L | 5675 | ||||

| MARC0048752 | 7 | 103,789,642 | QTL 3 | AREL1 | 5892 |

| M1GA0010654 | 7 | 103,796,933 | FCF1, YLPM1, PROX2, DLST and RPS6KL1 | Inside | |

| ALGA0043962 | 7 | 103,816,521 | |||

| H3GA0022664 | 7 | 103,910,821 | |||

| ASGA0035527 | 7 | 103,933,199 | |||

| DIAS0001088 | 7 | 103,960,033 | |||

| M1GA0010658 | 7 | 103,999,954 | – | LOC102167367 | 26,610 |

| PGF | Inside | ||||

| ASGA0035536 | 7 | 104,108,293 | – | MLH3 | 16,923 |

| LOC102167860 | 5573 | ||||

| ACYP1 | Inside | ||||

| ZC2HC1C | 1044 | ||||

| NEK9 | 11,806 | ||||

| ALGA0122954 | 7 | 104,598,913 | – | JDP2 | Inside |

| LOC100624918/FLVCR2 | 8951 | ||||

| ASGA0035556 | 7 | 105,224,235 | – | TGFB3 | 14,323 |

| IFT43 | Inside | ||||

| MARC0093074 | 8 | 50,223,543 | QTL 1 | LOC102166479, C8H4orf45 and RAPGEF2 | Inside |

| H3GA0024861 | 8 | 50,329,649 | |||

| H3GA0024862 | 8 | 50,359,681 | |||

| H3GA0024868 | 8 | 50,479,231 | |||

| H3GA0052920 | 8 | 50,503,562 | |||

| ASGA0038804 | 8 | 50,537,893 | |||

| DRGA0008588 | 8 | 51,580,681 | – | – | – |

| MARC0077695 | 8 | 53,929,233 | – | – | – |

| ALGA0047895 | 8 | 55,647,917 | QTL 2 | LOC102159670 | Inside |

| H3GA0024880 | 8 | 55,670,008 | |||

| H3GA0024879 | 8 | 55,749,069 | |||

| ALGA0047896 | 8 | 56,064,449 | |||

| ASGA0038818 | 8 | 56,175,366 | – | – | – |

| H3GA0024884 | 8 | 56,642,918 | QTL 3 | – | – |

| ASGA0038820 | 8 | 56,673,496 | |||

| H3GA0024882 | 8 | 56,695,265 | |||

| ASGA0038822 | 8 | 56,764,454 | |||

| ALGA0047901 | 8 | 56,805,057 | |||

| MARC0013221 | 8 | 57,262,741 | – | LOC100519853/ZNF320 | Inside |

| LOC102160850 | 692 | ||||

| INRA0029832 | 8 | 58,466,955 | QTL 4 | LOC102165777, NMU, LOC102166140, PDCL2, LOC102166866, CLOCK and LOC100523623/TMEM165 | Inside |

| ALGA0047932 | 8 | 58,557,889 | |||

| ALGA0047933 | 8 | 58,625,849 | |||

| M1GA0011944 | 8 | 58,807,576 | SRD5A3 | 13,606 | |

| MARC0000554 | 8 | 67,026,060 | – | LOC100737487/EPHA5-like | Inside |

| ASGA0085207 | 8 | 69,065,977 | QTL 5 | – | – |

| MARC0020237 | 8 | 69,070,421 | |||

| MARC0095739 | 8 | 69,146,481 | |||

| ALGA0103392 | 8 | 69,146,919 | |||

| ALGA0102491 | 8 | 69,215,722 | |||

| ALGA0066725 | 12 | 50,281,949 | QTL 1 | METTL16, PAFAH1B1, LOC102165360, CLUH, LOC102165602/CCDC92 | Inside |

| ASGA0054883 | 12 | 50,340,265 | |||

| MARC0027202 | 12 | 50,489,072 | |||

| ALGA0066740 | 12 | 50,578,018 | |||

| DIAS0001557 | 12 | 55,962,023 | – | PFAS | 11,951 |

| RANGRF | Inside | ||||

| SLC25A35 | 163 | ||||

| ARHGEF15 | 8954 | ||||

| ODF4 | 31,445 | ||||

| ASGA0062949 | 14 | 43,688,399 | – | TRPV4 | 4852 |

| FAM222A | 4716 |

The table shows significant SNPs, their positions in base pairs (bp) on the swine chromosome (Chr), the QTL region, associated genes (genes located in a QTL region or in an interval of 32.5 Kbp around each QTL region or SNP), followed by their distance in base pairs of a single marker or in relation to the first or last SNP of the region

aGene location in relation to the QTL region or to the single SNP

Gene-TF networks

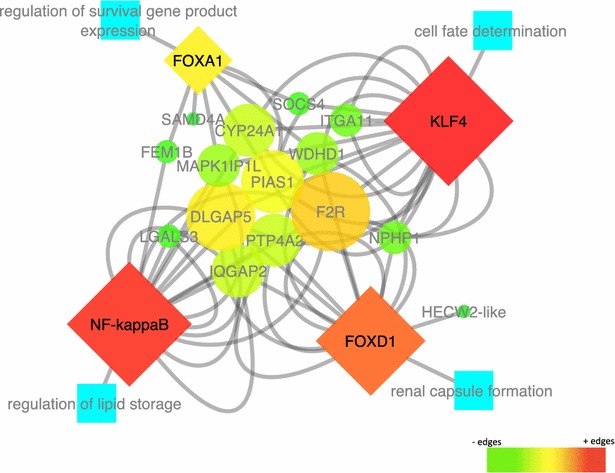

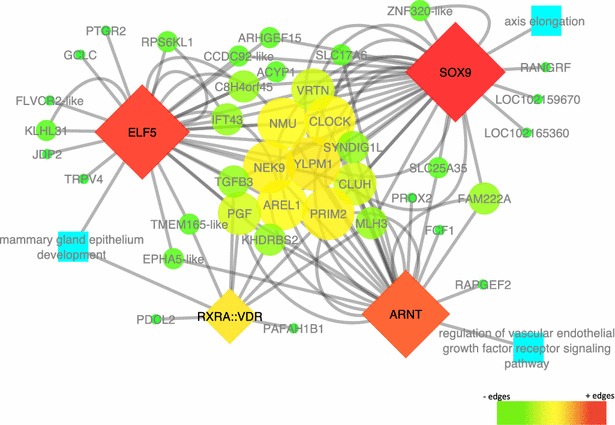

Information about biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions of all identified genes was based on human gene annotations, since they are more thorough and accurate than pig genome annotations [See Additional file 11: Table S3 and Additional file 12: Table S4]. Using the TFM-explorer, regulatory sequence analyses were performed to identify TF that were strongly related (p value <0.0001) to each set of genes for each trait [See Additional file 13: Table S5 and Additional file 14: Table S6]. The most representative TF genes (FOXA1, FOXD1, NF-kappaB, and KLF4 for SB and ARNT, ELF5, RXRA::VDR, and SOX9 for NT), according to the biological processes in which they are involved and to data in the literature, (e.g. TF involved with kidney diseases and diabetes for SB and TF related to mammary gland tissue and vertebrae composition and spinal cord expression for NT) were chosen to achieve a gene-TF network (Figs. 2, 3). Based on these networks, we were able to identify the most likely candidate genes for SB (CYP24A1, DLGAP5, F2R, IQGAP2, LGALS3, MAPK1IP1L, NPHP1, PTP4A2, PIAS1, and WDHD1) and NT (PRIM2, AREL1, CLOCK, NEK9, NMU, SYNDIG1L, TGFB3, TMEM165-like,VRTN, and YLPM1).

Fig. 2.

Stillbirth gene-transcription factor (TF) network. Four transcription factors associated with genes involved in stillbirth: NF-κB, FOXA1, KLF4, and FOXD1 (diamond nodes), with in silico validated targets (circle nodes). Their color scale and size corresponds to network analyses (Cytoscape) scores, where red and bigger nodes represent higher edge densities, while green and smaller nodes represent lower edge densities. Blue nodes are the transcription factor related biological processes

Fig. 3.

Number of teats gene-transcription factor network. Four transcription factors associated with genes involved in number of teats: SOX9, ELF5, RXRA::VDR, and ARNT (diamond nodes), with in silico validated target genes (circle nodes). Their color scale and size corresponds to network analyses (Cytoscape) scores, where red and bigger nodes represent higher edge densities, while green and smaller nodes represent lower edge densities. Blue nodes are the transcription factor related biological processes

Discussion

Based on DIC (Fig. 1), the Poisson model showed the best fit for SB, while the Gaussian model showed the best fit for NT. Most studies do not consider the Poisson distribution for SB [52], although the use of discrete distributions can lead to a more appropriate quantification of the genetic influences on this trait. Working under a hierarchical Bayesian approach, Varona and Sorensen [53] demonstrated the importance of proposing and comparing discrete distributions for SB data in animal breeding.

Although NT is also characterized as a discrete counting variable, the Gaussian distribution fits the behavior of this trait better than the Poisson distribution. A possible reason is that the Poisson distribution is asymmetric and right skewed, and the symmetry of the Gaussian distribution was more consistent with the observed distribution of the NT sample data. Another explanation is that the Poisson distribution assumes that the mean is equal to its variance, a condition that may not have been met when working with NT, even when assuming an extra residual term (Model 2). In addition, the mean of NT (15.3) was much larger than the mean of SB (1.2), and the Gaussian distribution is a reasonable approximation for the Poisson distribution when the mean is greater than 10. In future studies, it would be interesting to consider other distributions for discrete random variables for which such a constraint (mean equal to variance) is not required, e.g. the negative binomial and generalized Poisson distributions, as proposed by Varona and Sorensen [53].

The GWAS for SB identified 18 significant SNPs that were on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 6, 15, 16, and 17, along with one QTL region on chromosome 1 (Table 1). Several QTL for SB were previously reported near the chromosomal regions that were identified in this study for chromosomes 1, 6, 16, and 17 [2]. For NT, the GWAS identified 65 significant SNPs on chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 9, 11, and 14, along with QTL regions identified on chromosome 7, 8, and 12 (Table 2). Several previously reported QTL for NT were located in the same chromosomal regions in which SNPs and QTL were identified in this study [38, 54–57]. Identification of these SNPs that were associated with SB and NT in the GWAS and the replication of QTL that were identified in other studies gave us more confidence to evaluate the SNP effects and the biological function of their related genes when using post-GWAS analyses, such as gene-TF network analyses, which allowed us to propose a link between the traits, QTL, and overlapping genes.

Gene-TF networks

Based on single SNPs and QTL regions, we identified 18 and 57 genes, for SB and NT, respectively. From these genes, we collected information about their GO terms and pathways (e.g. renal system and reproductive biological processes for SB genes and glandular epithelial cell and mammary gland development biological processes for NT genes). The promoter regions that were enriched in the most relevant TF for each trait based on the biological process in which they were involved and on data from the literature, were investigated for each set of genes for each trait to generate gene-TF networks that highlighted the most likely candidate genes for SB and NT.

Stillbirth

Three of the four TF found for the SB gene-TF network (NF-κB, FOXA1, and FOXD1) have been reported to be involved in (human) kidney disease and diabetes [58–60]. These maternal diseases are associated with an elevated risk of stillbirth in humans [3–5]. The fourth TF found for the SB gene-TF network (KLF4) is related to vascular and cardiac disease [61]. Heart disease is one of the major causes of mortality and morbidity in the human perinatal period [5]. Among pregnant diabetic women, fetal hypoxia and cardiac dysfunction secondary to poor glycemic control are suggested as important pathogenic factors in stillbirths [4].

With these TF, we constructed a network that identified new candidate genes for SB (F2R, IQGAP2, PTP4A2, WDHD1, PIAS1, DLGAP5, MAPK1IP1L, SOCS4, NPHP1, and CYP24A1). DLGAP5 was one of the most highly connected genes in the gene-TF network. Fragoso et al. [62] indicated that it is a strong predictor of adrenocortical tumors and it is known that adrenocortical functions are linked to renal diseases [63] that are associated with SB. F2R was another well-connected gene, which has a role in congenital heart disease [64]. In the network, these two genes were connected to each other through the NF-κB, KLF4, and FOXD1 TF, which are related to kidney and heart diseases, thereby linking them with stillbirths.

In humans, a diabetic pregnancy affects the occurrence of stillbirths. In the SB network, CYP24A1 was one of the well-connected genes and it has been shown to be significantly more expressed in placental tissue from women with gestational diabetes mellitus [65]. Other genes in the SB network related to diabetes are PTP4A2, IQGAP2, and SOCS4 [66–68]. Nephronophthisis 1 (NPHP1) was another strong candidate gene that was identified and is associated with juvenile nephronophthisis and Joubert Syndrome (JS) [69]. One of the key symptoms of JS is breathing abnormality during the neonatal period [70], which could also be linked to the occurrence of SB. Using this gene-TF network, we were able to confirm genes that are linked to SB, not only through their position at a QTL, but also through a known biological role.

Number of teats

The TF SOX9 and ARNT from the NT gene-TF network are mainly involved with vertebrae composition and spinal cord expression. For example, SOX9 has been shown to be involved with campomelic dysplasia [71], a syndrome which, among other symptoms, is characterized by vertebrae malformation and a smaller number of ribs [72]. ARNT, a gene that encodes an aryl hydrocarbon nuclear regulatory factor and is expressed in the spinal cord during mouse development [73], and ELF5 and VDR that are involved with mammary gland tissue development [74, 75] were detected in the GO analyses based on their association with biological processes of the mammary gland development (see the gene-TF network in Fig. 3).

With these TF, we constructed a network that identified new candidate genes for NT (PRIM2, AREL1, YLPM1, NEK9, NMU, CLOCK, SYNDIG1L, TMEM165-like, TGFB3, and VRTN). Among these genes, YLPM1 was one of the well connected genes in the network and plays a role in the reduction of telomerase activity during differentiation of embryonic stem cells [76]. Another well connected gene in this network is PRIM2, which encodes a DNA primase (large subunit) and contains a significant SNP that was found to be associated with body length in a LW × Minzhu pig population [77]. Linked with this group of genes, we found genes that are related to the number of vertebrae such as PROX2, VRTN, and SYNDIG1L [38, 78], which may be related with the NT in pigs [8, 31]. The chromosomal regions that contain each of these genes have been explored in detail because they are significantly associated with NT [31, 38]. Other well connected genes in the gene-TF network are NMU, which is related to bone formation [79], and TGFB3, which is significantly associated with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine in humans [80]. TMEM165-like that is connected with two TF is associated with the mammary gland epithelium development GO term, and has been reported to be linked to developing, lactating, and involuting mammary gland [81]. These genes, as well as AREL1, NEK9 and CLOCK that have been studied in detail at the molecular level were highlighted in the network as the most likely candidate genes for NT.

Conclusions

We showed that the Poisson distribution best fitted the data for number of SB, whereas the Gaussian distribution was superior for NT in pig. To determine, which distribution is best for count traits in GWAS, both the Poisson and Gaussian distributions, together with other discrete distributions, should be tested. For both SB and NT, we observed associations between significant SNPs and genes that include these SNPs. The present study also provides information about these genes, thereby increasing our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underlie SB and NT. In addition, we predicted gene interactions that were consistent with known newborn survival traits and mammary gland biology in mammals, and that led to the identification of candidate genes for SB (e.g. DLGAP5, PTP4A2, IQGAP2, SOCS4, CYP24A1, F2R, and NPHP1) and NT (e.g. YLPM1, PROX2, VRTN, SYNDIG1L, PRIM2, TMEM165-like, NMU, and TGFB3). Our results highlighted TF that may have an important role for SB and NT (e.g. NF-kappaB and KLF4 for SB and SOX9 and ELF5 for NT). Nevertheless, these are complex traits that are subject to the action of a large number of genes that are regulated by several TF, many of which have yet to be identified.

Authors’ contributions

LLV, FFS, and SEFG planned the experiment. LLV, FFS, MSL, and MK ran the analyses. LLV, FFS, MSL, OM, SEFG, JWMB, PSL, EFK, LV, MD, and MK contributed to drafting the manuscript. PSL and EK contributed to the conception of the study and provided data for writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), National Institute of Science and Technology–Animal Science, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES/NUFFIC and CAPES/DGU), and Institute for Pig Genetics-IPG (Topigs Norsvin).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional files

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Histograms and descriptive statistics for the p values of the Geweke convergence test for breeding values (a and b) and SNP effects (c and d), respectively for the traits SB and NT.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Trace plots and empirical distributions for the two most significant SNPs for SB.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Trace plots and empirical distributions for the two most significant SNPs for NT.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Density of stillborn (SB) and number of teats (NT) data when considering the observed, Poisson and Gaussian curves.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Significant SNPs, position, and chromosome (chr) location on the S. scrofa reference genome (10.2), posterior mean, posterior probability under H0 (PPN0), and 95 % HPD (Highest Posterior Density) interval limits for SB.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Significant SNPs, position, and chromosome (chr) location on the S. scrofa reference genome (10.2), posterior mean, posterior probability under H0 (PPN0), and 95 % HPD (Highest Posterior Density) interval limits for NT.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Graphical summary (Manhattan plot) of genome-wide association results for SB. The x axis represents the genome in physical order, while the y axis shows the posterior probability under H0 (PPN0) for all SNPs.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Graphical summary (Manhattan plot) of genome-wide association results for NT. The x axis represents the genome in physical order, while the y axis shows the posterior probability under H0 (PPN0) for all SNPs.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x QTL region on chromosome 1 (Chr 1) that contains significant SNPs for SB. Solid lines mark the QTL region.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x QTL regions on chromosomes 7, 8, and 12 (Chr 7, Chr 8, and Chr 12 respectively) that contain significant SNPs for NB. Solid lines mark the QTL regions.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Pathway and Gene Ontology terms (GO) of genes associated with significant SNPs identified for SB.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Pathway and Gene Ontology terms (GO) of genes associated with significant SNPs identified for NT.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Transcription factors (TF) identified for genes associated with SB, location in base pairs (bp) of the window sequence that carries binding sites, and p-value of the window confidence that was obtained from the TFM-explorer tool.

10.1186/s12711-016-0189-x Transcription factors (TF) identified for genes associated with NT, location in base pairs (bp) of the window sequence that carries binding sites, and p-value of the window confidence that was obtained from the TFM-explorer tool.

Contributor Information

Lucas L. Verardo, Email: lucas_verardo@yahoo.com.br

Fabyano F. Silva, Email: fabyanofonseca@ufv.br

Marcos S. Lopes, Email: Marcos.Lopes@topigsnorsvin.com

Ole Madsen, Email: ole.madsen@wur.nl.

John W. M. Bastiaansen, Email: john.bastiaansen@wur.nl

Egbert F. Knol, Email: egbert.knol@topigsnorsvin.com

Mathew Kelly, Email: m.kelly7@uq.edu.au.

Luis Varona, Email: lvarona@unizar.es.

Paulo S. Lopes, Email: plopes@ufv.br

Simone E. F. Guimarães, Email: sfacioni@ufv.br

References

- 1.Blasco A, Bidanel JP, Haley CS. Genetics and neonatal survival. In: Varley MA, editor. The neonatal pig: development and survival. Wallingford: CABI; 1995. pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onteru SK, Fan B, Du ZQ, Garrick DJ, Stalder KJ, Rothschild MF. A whole-genome association study for pig reproductive traits. Anim Genet. 2012;43:18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nevis IF, Reitsma A, Dominic A, McDonald S, Thabane L, Akl EA, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2587–2598. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10841210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathiesen ER, Ringholm L, Damm P. Stillbirth in diabetic pregnancies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee K, Khoshnood B, Chen L, Stephen NW, Cromie JW, Mittendorf RL. Infant mortality from congenital malformations in the United States, 1970–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:620–627. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirooka H, de Koning DJ, Harlizius B, van Arendonk JA, Rattink AP, Groenen MA, et al. A whole-genome scan for quantitative trait loci affecting teat number in pigs. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:2320–2326. doi: 10.2527/2001.7992320x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hens JR, Wysolmerski JJ. Key stages of mammary gland development: molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of the embryonic mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:220–224. doi: 10.1186/bcr1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren DR, Ren J, Ruan GF, Guo YM, Wu LH, Yang GC, et al. Mapping and fine mapping of quantitative trait loci for the number of vertebrae in a White Duroc × Chinese Erhualian intercross resource population. Anim Genet. 2012;43:545–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uimari P, Sironen A, Sevón-Aimonen ML. Whole-genome SNP association analysis of reproduction traits in the Finnish Landrace pig breed. Genet Sel Evol. 2011;43:42. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-43-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider JF, Rempel LA, Rohrer GA. Genome-wide association study of swine farrowing traits. Part I: genetic and genomic parameter estimates. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:3353–3359. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Enciso M, Tempelman RJ, Gianola D. A comparison between linear and Poisson mixed models for litter size in Iberian pigs. Livest Prod Sci. 1993;35:303–316. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(93)90100-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayres DR, Pereira RJ, Boligon AA, Silva FF, Schenkel FS, Roso VM, et al. Linear and Poisson models for genetic evaluation of tick resistance in cross-bred Hereford x Nellore cattle. J Anim Breed Genet. 2013;130:417–424. doi: 10.1111/jbg.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui Y, Kim DY, Zhu J. On the generalized Poisson regression mixture model for mapping quantitative trait loci with count data. Genetics. 2006;174:2159–2172. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva KM, Bastiaansen JWM, Knol EF, Merks JWM, Lopes PS, Guimarães SEF, et al. Meta-analysis of results from quantitative trait loci mapping studies on pig chromosome 4. Anim Genet. 2011;42:280–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadfield JD, Nakagawa S. General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. J Evol Biol. 2010;23:494–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Raden PM. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:4414–4423. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stranden I, Garrick DJ. Derivation of equivalent computing algorithms for genomic predictions and reliabilities of animal merit. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:2971–2975. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Misztal I, Aguilar I, Legarra A, Muir WM. Genome-wide association mapping including phenotypes from relatives without genotypes. Genet Res (Camb) 2012;94:73–83. doi: 10.1017/S0016672312000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, Gopal V, Li X, Davis JM, Casella G. Simultaneous SNP identification in association studies with missing data. Ann Appl Stat. 2012;6:432–456. doi: 10.1214/11-AOAS516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramírez O, Quintanilla R, Varona L, Gallardo D, Díaz I, Pena RN, Amills M. DECR1 and ME1 genotypes are associated with lipid composition traits in Duroc pigs. J Anim Breed Genet. 2014;131:46–52. doi: 10.1111/jbg.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cecchinato A, Ribeca C, Chessa S, Cipolat-Gotet C, Maretto F, Casellas J, et al. Candidate gene association analysis for milk yield, composition, urea nitrogen and somatic cell scores in Brown Swiss cows. Animal. 2014;7:1062–1070. doi: 10.1017/S1751731114001098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirina A, Atzmon G, Ye K, Bergman A. Gene size matters. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu TP, Tuggle CK, Schmitz CB, Rothschild MF. Association of PIT1 polymorphisms with growth and carcass traits in pigs. J Anim Sci. 1995;73:1282–1288. doi: 10.2527/1995.7351282x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Yang XJ, Xia D, Chen J, Wegner J, Jiang Z, et al. Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 expression and genetic polymorphism significantly affect intramuscular fat deposition in the longissimus muscle of Erhualian and Sutai pigs. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:57–63. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fortes MR, Reverter T, Nagaraj SH, Zhang Y, Jonsson NN, Barris W, et al. A SNP-derived regulatory gene network underlying puberty in two tropical breeds of beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:1669–1683. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reverter A, Fortes MRS. Building single nucleotide polymorphism-derived gene regulatory networks: towards functional genomewide association studies. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:530–536. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verardo LL, Silva FF, Varona L, Resende MDV, Bastiaansen JWM, Lopes PS, et al. Bayesian GWAS and network analysis revealed new candidate genes for number of teats in pigs. J Appl Genet. 2015;56:123–132. doi: 10.1007/s13353-014-0240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos AM, Crooijmans RPMA, Affara NA, Amaral AJ, Archibald AL, Beever JE, et al. Design of a high density SNP genotyping assay in the pig using SNPs identified and characterized by next generation sequencing technology. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliphant A, Barker DL, Stuelpnagel JR, Chee MS. BeadArray technology: enabling an accurate, cost-effective approach to high-throughput genotyping. Biotechniques. 2002;Suppl56-8, 60-1. [PubMed]

- 30.Groenen MA, Archibald AL, Uenishi H, Tuggle CK, Takeuchi Y, Rothschild MF, et al. Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature. 2012;491:393–398. doi: 10.1038/nature11622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopes MS, Bastiaansen JW, Harlizius B, Knol EF, Bovenhuis H. A genome-wide association study reveals dominance effects on number of teats in pigs. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foulley JL, Gianola D, Im S. Genetic evaluation of traits distributed as Poisson-binomial with reference to reproductive traits. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;73:870–877. doi: 10.1007/BF00289392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tempelman RJ, Gianola D. A mixed effects model for overdispersed count data in animal breeding. Biometrics. 1996;52:265–279. doi: 10.2307/2533161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun D, Speckman PL, Tsutakawa RK. Random effects in generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) In: Dey DK, Ghosh SK, Mallick BK, editors. Generalized linear models: A Bayesian perspective. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorensen D, Gianola D. Uncertainty about functions of random variables. In: likelihood, Bayesian, and MCMC methods in quantitative genetics. New York: Springer-Verlarg; 2002.

- 36.Rashidi H, Mulder HA, Mathur P, van Arendonk JAM, Knol EF. Variation among sows in response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. Anim Sci. 2014;92:95–105. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrero-Medrano JM, Mathur PK, ten Napel J, Rashidi H, Alexandri P, Knol EF, et al. Estimation of genetic parameters and breeding values across challenged environments to select for robust pigs. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:1494–1502. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duijvesteijn N, Veltmaat JM, Knol EF, Harlizius B. High-resolution association mapping of number of teats in pigs reveals regions controlling vertebral development. BMC Genom. 2014;15:542. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hadfield JD. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22. doi: 10.18637/jss.v033.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Statist Soc B. 2002;64:583–639. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plummer M, Best N, Cowles K, Vines K. CODA: convergence diagnosis and output analysis for MCMC. R News. 2006;6:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aguilar I, Misztal I, Legarra A, Tsuruta S. Efficient computation of the genomic relationship matrix and other matrices used in single-step evaluation. J Anim Breed Genet. 2011;128:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0388.2010.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewontin RC. The interaction of selection and linkage. I. General considerations; heterotic models. Genetics. 1964;49:49–67. doi: 10.1093/genetics/49.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veroneze R, Bastiaansen JW, Knol EF, Guimarães SE, Silva FF, Harlizius B, et al. Linkage disequilibrium patterns and persistence of phase in purebred and crossbred pig (Sus scrofa) populations. BMC Genet. 2014;15:126. doi: 10.1186/s12863-014-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meuwissen TH, Hayes BJ, Goddard ME. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics. 2001;157:1819–1829. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engström P, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D91–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Touzet H, Varré JS. Efficient and accurate P-value computation for Position Weight Matrices. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2007;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canario L, Cantoni E, Le Bihan E, Caritez JC, Billon Y, Bidanel JP, et al. Between-breed variability of stillbirth and its relationship with sow and piglet characteristics. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:3185–3196. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varona L, Sorensen D. A genetic analysis of mortality in pigs. Genetics. 2010;184:277–284. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.110759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo YM, Lee GJ, Archibald AL, Haley CS. Quantitative trait loci for production traits in pigs: a combined analysis of two Meishan x Large White populations. Anim Genet. 2008;39:486–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee SS, Chen Y, Moran C, Cepica S, Reiner G, Bartenschlager H, et al. Linkage and QTL mapping for Sus scrofa chromosome 2. J Anim Breed Genet. 2003;120:11–19. doi: 10.1046/j.0931-2668.2003.00419.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.King AH, Jiang Z, Gibson JP, Haley CS, Archibald AL. Mapping quantitative trait loci affecting female reproductive traits on porcine chromosome 8. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:2172–2179. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.012955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato S, Atsuji K, Saito N, Okitsu M, Sato S, Komatsuda A, et al. Identification of quantitative trait loci affecting corpora lutea and number of teats in a Meishan × Duroc F2 resource population. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:2895–2901. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mezzano S, Aros C, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ardiles L, Flores C, et al. NF-KB activation and overexpression of regulated genes in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2505–2512. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Behr R, Brestelli J, Fulmer JT, Miyawaki N, Kleyman TR, Kaestner KH. Mild nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by Foxa1 deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41936–41941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levinson RS, Batourina E, Choi C, Vorontchikhina M, Kitajewski J, Mendelsohn CL. Foxd1-dependent signals control cellularity in the renal capsule, a structure required for normal renal development. Development. 2005;132:529–539. doi: 10.1242/dev.01604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshida T, Yamashita M, Horimai C, Hayashi M. Deletion of Krüppel-like factor 4 in endothelial and hematopoietic cells enhances neointimal formation following vascular injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000622. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fragoso MCB, Almeida MQ, Mazzuco TL, Mariani BM, Brito LP, Gonçalves TC, et al. Combined expression of BUB1B, DLGAP5, and PINK1 as predictors of poor outcome in adrenocortical tumors: validation in a Brazilian cohort of adult and pediatric patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:61–67. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arregger AL, Cardoso EM, Zucchini A, Aguirre EC, Elbert A, Contreras LN. Adrenocortical function in hypotensive patients with end stage renal disease. Steroids. 2014;84:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gigante B, Bellis A, Visconti R, Marino M, Morisco C, Trimarco V, et al. Retrospective analysis of coagulation factor II receptor (F2R) sequence variation and coronary heart disease in hypertensive patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1213–1219. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.140541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cho GJ, Hong SC, Oh MJ, Kim HJ. Vitamin D deficiency in gestational diabetes mellitus and the role of the placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:560.e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kakoola DN, Curcio-Brint A, Lenchik NI, Gerling IC. Molecular pathway alterations in CD4 T-cells of nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice in the preinsulitis phase of autoimmune diabetes. Results Immunol. 2014;4:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rinim.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woroniecka KI, Park ASD, Mohtat D, Thomas DB, Pullman JM, Susztak K. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2011;60:2354–2369. doi: 10.2337/db10-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feng X, Tang H, Leng J, Jiang Q. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) and type 2 diabetes. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:2265–2274. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parisi MA, Bennett CL, Eckert ML, Dobyns WB, Gleeson JG, Shaw DW, et al. The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:82–91. doi: 10.1086/421846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saravia JM, Baraister M. Joubert syndrome: a review. Am J Med Genet. 1992;43:726–731. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320430415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wunderle VM, Critcher R, Hastie N, Goodfellow PN, Schedl A. Deletion of long-range regulatory elements upstream of SOX9 causes campomelic dysplasia. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10649–10654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mansour S, Hall CM, Pembrey ME, Young ID. A clinical and genetic study of campomelic dysplasia. J Med Genet. 1995;32:415–420. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.6.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jain S, Maltepe E, Lu MM, Simon C, Bradfield CA. Expression of ARNT, ARNT2, HIF1α, HIF2 α and Ah receptor mRNAs in the developing mouse. Mech Dev. 1998;73:117–123. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choi YS, Chakrabarti R, Escamilla-Hernandez R, Sinha S. Elf5 conditional knockout mice reveal its role as a master regulator in mammary alveolar development: failure of Stat5 activation and functional differentiation in the absence of Elf5. Dev Biol. 2009;329:227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Welsh J, Wietzke JA, Zinser GM, Smyczek S, Romu S, Tribble E, et al. Impact of the Vitamin D3 receptor on growth-regulatory pathways in mammary gland and breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83:85–92. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(02)00277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blalock WL, Piazzi M, Bavelloni A, Raffini M, Faenza I, D’Angelo A, et al. Identification of the PKR nuclear interactome reveals roles in ribosome biogenesis, mRNA processing and cell division. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1047–1060. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang L, Zhang L, Yan H, Liu X, Li N, Liang J, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify the loci for 5 exterior traits in a Large White × Minzhu pig population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pistocchi A, Bartesaghi S, Cotelli F, Del Giacco L. Identification and expression pattern of zebrafish prox2 during embryonic development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3916–3920. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sato S, Hanada R, Kimura A, Abe T, Matsumoto T, Iwasaki M, et al. Central control of bone remodeling by neuromedin U. Nat Med. 2007;13:1234–1240. doi: 10.1038/nm1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Horikoshi T, Maeda K, Kawaguchi Y, Chiba K, Mori K, Koshizuka Y, et al. A large-scale genetic association study of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Hum Genet. 2006;119:611–616. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reinhardt TA, Lippolis JD, Sacco RE. The Ca2+/H+ antiporter TMEM165 expression, localization in the developing, lactating and involuting mammary gland parallels the secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase (SPCA1) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]