Abstract

Systemic chemotherapy comprising anthracycline monotherapy is the standard regimen for metastatic soft tissue sarcomas, particularly leiomyosarcomas, which have limited sensitivity to ifosfamide. However, the optimal chemotherapy regimen for elderly patients, especially those considered unfit for anthracyclines, is undefined. Trabectedin is a potent marine-derived antineoplastic drug with documented activity in liposarcomas and leiomyosarcomas. It is registered in Europe for the treatment of adult patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma, after failure of anthracyclines and ifosfamide, or who are unsuited to receive these agents. We report the long-term response to first-line trabectedin therapy in an elderly patient with metastatic leiomyosarcoma unfit for standard therapy. A 66-year-old woman underwent resection of a pelvic epithelioid leiomyosarcoma with positive margins in December 2002, followed by postoperative radiotherapy. In February 2012, she was diagnosed with multiple lung lesions and local relapse in the pelvis. As she was considered unsuitable for both anthracycline and ifosfamide because of cardiovascular comorbidities and because she was highly anxious at the prospect of developing alopecia, vomiting, and fatigue, we commenced treatment with trabectedin at 75% of the standard dose of 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Treatment was well tolerated, and the patient continued treatment for 25 cycles, with disease stabilization according to the RECIST criteria and a partial response according to the Choi criteria. Disease progression was observed in November 2013 and the patient died 20 months after the diagnosis of metastases. Trabectedin may represent an alternative option for highly selected elderly patients with metastatic sarcoma and unfit for anthracyclines; careful monitoring of toxicities is strongly recommended.

Keywords: first-line chemotherapy, leiomyosarcoma, response, trabectedin

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas comprise more than 50 histological subtypes that are associated with varying outcomes depending on intrinsic biology diversity as well as heterogeneous responses to chemotherapy 1. Patients with metastatic disease have a median overall survival of about 12 months 2 and anthracycline monotherapy remains the standard reference regimen. The adjunct of high-dose ifosfamide failed to improve overall survival at the cost of increased toxicities in several trials, including a recent publication by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer – Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (EORTC-STBSG), although a significant improvement of response rate (26 vs. 14%; P<0.0006) and median progression-free survival (PFS) (7.4 vs. 4.6 months, P=0.003) was observed with combined therapy and could represent a relevant clinical benefit 3. The sensitivity of leiomyosarcomas to ifosfamide is considered to be inferior to that of other histotypes 4. Currently, the efficacy and toxicity of first-line chemotherapy in elderly sarcoma patients is poorly described. It is widely recognized that age is an independent risk factor for anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy 5 and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy may be poorly tolerated in elderly patients, in whom comorbidities may worsen the incidence and severity of expected side effects such as myelosuppression, mucositis, and cardiovascular events. A phase II EORTC-STBSG randomized clinical trial compared pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with doxorubicin monotherapy in a population of patients with metastatic sarcomas of mixed histology, with leiomyosarcoma in 33% and also some chemoresistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) 6.

Although the trial showed that pegylated liposomal doxorubicin could have equivalent activity to doxorubicin with an improved toxicity profile, no further development of this drug has been planned for the elderly population with sarcoma, in contrast to older women with breast cancer 7. Therefore, the optimal chemotherapy regimen for elderly patients, especially those considered to be unfit as defined using multidimensional geriatric assessment 8, remains undefined. Trabectedin, a potent antineoplastic drug derived from the marine tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata and currently manufactured by total synthesis 9, has been approved for the second-line treatment of advanced sarcomas in 2007 after showing appreciable rates of clinical benefit especially in leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma 10–13. The standard dose for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma is 1.5 mg/m2 administered as an intravenous infusion over 24 h every 3 weeks; dose reductions are allowed according to the tolerability in the patient 14. The main toxicities with trabectedin are nausea and vomiting, sickness, myelosuppression, fatigue, and transaminitis, all of which are usually reversible with no relevant cardiovascular consequences or alopecia. The drug is currently registered in Europe for metastatic sarcomas in patients unsuitable for or after failure of anthracycline and ifosfamide 14. Trabectedin, therefore, represents an attractive treatment option for elderly patients with advanced sarcomas, especially those with the so-called l-histologies (liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma).

Case presentation

In December 2002, a 66-year-old woman presented with a pelvic mass. Comorbidities included type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and mild psychotic syndrome; home therapy consisted of insulin, indapamide, perindopril, atorvastatin, and lorazepam. She underwent excision of the mass, which appeared to originate from the rectum. The histopathological diagnosis reported an epithelioid leiomyosarcoma with positive margins and postoperative radiotherapy was planned and completed in January 2003. Soon after completion of radiotherapy, the patient experienced a myocardial infarction that required coronary artery stenting plus long-term platelet antiaggregation therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel. Chest and abdomen computed tomographic scan was repeated every 3 to 4 months, but after 2 years, she preferred to continue clinical follow-up visits with her general practitioner.

In February 2012, the patient returned to the hospital following a diagnosis of multiple lung lesions and a large local relapse in the pelvis. A biopsy of the lung confirmed the mesenchymal origin of the disease. The patient underwent a full multidimensional geriatric evaluation 15 and was classified as vulnerable, with her daughter as a reliable sole caregiver.

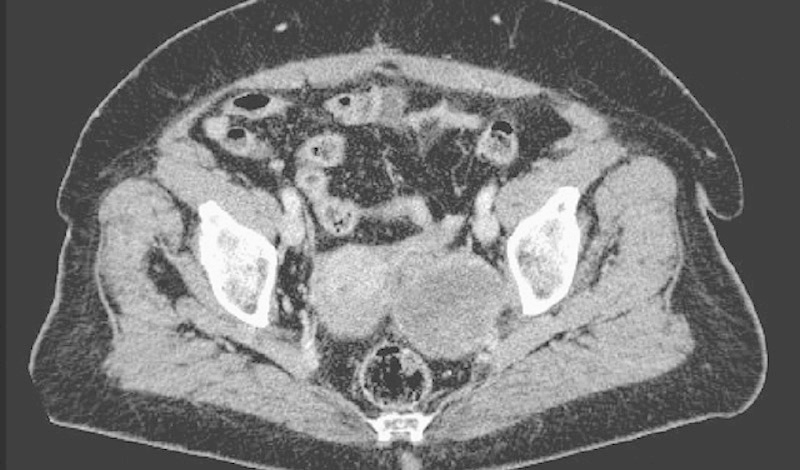

The patient was considered unsuitable for both anthracycline and ifosfamide because of her cardiovascular comorbidities and because she was highly anxious at the prospect of developing alopecia, vomiting, and fatigue, which could prevent her from receiving her girlfriends at home. She underwent several psycho-oncology consultations to control mild depressive symptoms, but she was deemed suitable to receive systemic chemotherapy. We proposed that she start trabectedin during April 2012 with standard dexamethasone premedication and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor prophylaxis. The dose was prudently reduced to 75% of the standard dose of 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks to limit the risk of severe vomiting and fatigue, which would heavily impact on the patient’s quality of life. Indeed, the patient experienced only moderate asthenia and a transient liver function alteration, but no grade 3 or 4 toxicities. She continued treatment with the same dosage of trabectedin for a total of 25 cycles. Best response was stabilization according to the RECIST criteria 16, although a reduction of lesion density at cycle 22 could be deemed as a partial response according to the Choi criteria 17 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pelvic localization of leiomyosarcoma showing density reduction after treatment with trabectedin.

At the end of November 2013, the patient complained of abdominal pain and her general condition deteriorated rapidly. The new computed tomographic scan showed multifocal radiological progression; therefore, trabectedin was stopped after 25 cycles. She was admitted to a nursing home and died at the end of December 2013, 20 months after the diagnosis of metastases.

Discussion

Trabectedin has shown meaningful activity in advanced metastatic soft tissue sarcoma in phase II clinical trials, especially in leiomyosarcomas and liposarcomas 9,10,18. Very recently, a significant 45% reduction in the probability of progression in comparison with dacarbazine was found in a multinational randomized phase III trial in pretreated patients with either liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma 19. The drug was approved in 2007 by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of advanced sarcoma following conventional first-line chemotherapy or deemed unsuitable for other cytotoxic treatment 13. More recently, a retrospective pooled analysis addressed the role of trabectedin in the subgroup of patients older than 60 years enrolled in five phase II clinical trials, mainly as second-line chemotherapy 20. With the caveat of patient selection, comparable activity in terms of both PFS and overall survival were reported, with an increase of grade 3/4 neutropenia (60.2 vs. 43.6%) and fatigue (14.4 vs. 6.3%) compared with younger patients. The median overall survival was 14.0 months (range 9.5–23.9) in patients aged more than or equal to 60 years versus 13.0 months (range 11.3–14.9) in those less than 60 years and the corresponding median PFS was 3.7 (range 2.1–5.5) versus 2.5 months (range 1.9–3.1), respectively 20. The only trial of trabectedin in a first-line setting included in the analysis was conducted in 26 chemotherapy-naive patients and reported a good response rate (17.1%), with a median response duration of 16.5 months 21. A phase III randomized clinical trial evaluated the activity of trabectedin in comparison with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in untreated, advanced/metastatic translocation-related sarcomas 22. PFS and survival were comparable, but a higher incidence of severe neutropenia, alopecia, and mucositis was reported for doxorubicin-based treatment. In contrast to this, a phase IIb/III 62091 randomized trial conducted by the EORTC-STBSG, which compared two schedules of trabectedin against single-arm doxorubicin in the first-line setting of mixed metastatic sarcomas, failed to show superior activity of trabectedin at the price of increased rate of interruption because of toxicity 23.

Anthracycline-based regimens, therefore, remain the standard first-line regimen for metastatic sarcomas, but for selected patients with contraindications to anthracyclines, such as our cardiopathic patient with leiomyosarcoma, and a high anxiety state at the thought of developing chemotherapy-induced alopecia, trabectedin represents a more reasonable option.

In our patient, we obtained a disease stabilization according to RECIST, whereas we detected a partial response according to the Choi criteria. Different clinical experiences and a somewhat atypical response as may be observed with trabectedin suggest assessing response using the Choi criteria rather than RECIST 24, both in GIST 25 and in non-GIST sarcomas 11,26, even if the widespread introduction of these criteria is hampered by the limited reproducibility. Furthermore, the duration of chemotherapy with trabectedin is also a challenging issue. In a retrospective French study, PFS and overall survival were significantly improved in patients receiving continued treatment with trabectedin after six cycles 27. More recently, a prospective trial examined the question of whether treatment beyond six cycles in patients with stabilization or response should be continued 28. On the basis of improvement in PFS and 12-month survival with maintenance therapy, the authors recommend that trabectedin should be continued until progression, unacceptable toxicities, or patient’s choice, also taking into consideration the fact that prolonged administration of trabectedin may be well tolerated, with a limited number of grade 3 to 4 toxicities observed in the initial large trials 9,29. Transaminitis is commonly encountered, but is usually transient, tending to become less significant with repeated cycles, and may be reduced with adequate steroid premedication 30. In contrast, neutropenia continues to be a common side effect (∼69%), even if febrile neutropenia is rare (∼2%) 31. In our patient, no grade 3 or 4 toxicities were detected thanks to dose reduction and prophylactic use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Up-front dose reduction and growth factors are common strategies used in unfit elderly patients because acute severe toxicities, especially in the first cycle, may be life-threatening and may break the therapeutic alliance with the patient and his/her caregivers 8. Moreover, the absence of alopecia was an advantage particularly important for this patient, who was able to continue the treatment up to clinical progression after 25 cycles of therapy administered as an outpatient, achieving a prolonged stabilization of disease.

Conclusion

The present case shows that trabectedin represents a safe and effective first-line treatment for selected patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma unfit for anthracyclines and ifosfamide because of age and/or cardiologic comorbidities. A study from the Italian Sarcoma Group (EudraCT 2013-001467-23) is ongoing to assess the efficacy of trabectedin as a first-line treatment for advanced sarcomas in elderly or unfit patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ray Hill, an independent medical writer, who provided English-language editing and journal styling before submission on behalf of Health Publishing & Services Srl.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Oosterhuis JW, Mouridsen H, Crowther D, Somers R, et al. Prognostic factors for the outcome of chemotherapy in advanced soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 2185 patients treated with anthracycline-containing first-line regimens – a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group Study. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Judson I, Verweij J, Gelderblom H, Hartmann JT, Schöffski P, Blay JY, et al. European Organisation and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Doxorubicin alone versus intensified doxorubicin plus ifosfamide for first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15:415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, Seddon B. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma 2010; 2010:506182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, Davis HL, Jr, Von Hoff AL, Rozencweig M, Muggia FM. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med 1979; 91:710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judson I, Radford JA, Harris M, Blay JY, van Hoesel Q, le Cesne A, et al. Randomised phase II trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (DOXIL/CAELYX) versus doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a study by the EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37:870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basso U, Roma A, Brunello A, Falci C, Fiduccia P, Banzato A, et al. Bi-weekly liposomal doxorubicin for advanced breast cancer in elderly women (≥ 70 years). J Geriatr Oncol 2013; 4:340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monfardini S, Gridelli C, Pasetto LM, Soubeyran P, Droz JP, Basso U. Vulnerable and frail elderly: an approach to the management of the main tumour types. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44:488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Carbonero R, Supko JG, Manola J, Seiden MV, Harmon D, Ryan DP, et al. Phase II and pharmacokinetic study of ecteinascidin 743 in patients with progressive sarcomas of soft tissues refractory to chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:1480–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Judson I, Van Oosterom A, Verweij J, Radford J, et al. Phase II study of ET-743 in advanced soft tissue sarcomas: a European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) soft tissue and bone sarcoma group trial. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grosso F, Jones RL, Demetri GD, Judson IR, Blay JY, Le Cesne A, et al. Efficacy of trabectedin (ecteinascidin-743) in advanced pretreated myxoid liposarcomas: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8:595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demetri GD, Chawla SP, von Mehren M, Ritch P, Baker LH, Blay JY, et al. Efficacy and safety of trabectedin in patients with advanced or metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of prior anthracyclines and ifosfamide: results of a randomized phase II study of two different schedules. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:4188–4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grosso F, Sanfilippo R, Virdis E, Piovesan C, Collini P, Dileo P, et al. Trabectedin in myxoid liposarcomas (MLS): a long-term analysis of a single-institution series. Ann Oncol 2009; 20:1439–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2015. Yondelis (trabectedin): summary of product characteristics. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/. [Accessed September 2015].

- 15.Basso U, Monfardini S. Multidimensional geriatric evaluation in elderly cancer patients: a practical approach. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2004; 13:424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC, Macapinlac HA, Burgess MA, Patel SR, et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:1753–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samuels BL, Chawla S, Patel S, von Mehren M, Hamm J, Kaiser PE, et al. Clinical outcomes and safety with trabectedin therapy in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas following failure of prior chemotherapy: results of a worldwide expanded access program study. Ann Oncol 2013; 24:1703–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL, Hensley ML, Schuetze SM, Staddon A, et al. Efficacy and safety of trabectedin or dacarbazine for metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of conventional chemotherapy: results of a phase III randomized multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2015; 62:4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cesne AL, Judson I, Maki R, Grosso F, Schuetze S, Mehren MV, et al. Trabectedin is a feasible treatment for soft tissue sarcoma patients regardless of patient age: a retrospective pooled analysis of five phase II trials. Br J Cancer 2013; 109:1717–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Carbonero R, Supko JG, Maki RG, Manola J, Ryan DP, Harmon D, et al. Ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743) for chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas: multicenter phase II and pharmacokinetic study. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:5484–5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blay JY, Leahy MG, Nguyen BB, Patel SR, Hohenberger P, Santoro A, et al. Randomised phase III trial of trabectedin versus doxorubicin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in translocation-related sarcomas. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50:1137–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bui-Nguyen B, Butrynski JE, Penel N, Blay JY, Isambert N, Milhem M, et al. A phase IIb multicentre study comparing the efficacy of trabectedin to doxorubicin in patients with advanced or metastatic untreated soft tissue sarcoma: the TRUSTS trial. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51:1312–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maruzzo M, Martin-Liberal J, Messiou C, Miah A, Thway K, Alvarado R, et al. Pazopanib as first line treatment for solitary fibrous tumours: the Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Clin Sarcoma Res 2015; 5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi H. Response evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncologist 2008; 13 (Suppl 2):4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stacchiotti S, Collini P, Messina A, Morosi C, Barisella M, Bertulli R, et al. High-grade soft-tissue sarcomas: tumor response assessment – pilot study to assess the correlation between radiologic and pathologic response by using RECIST and Choi criteria. Radiology 2009; 251:447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Duffaud F, Chevreau C, Penel N, Bui Nguyen B, et al. French Sarcoma Group. Trabectedin in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a retrospective national analysis of the French Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51:742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Domont J, Tresch-Bruneel E, Chevreau C, Bertucci F, et al. Interruption versus continuation of trabectedin in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma (T-DIS): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yovine A, Riofrio M, Blay JY, Brain E, Alexandre J, Kahatt C, et al. Phase II study of ecteinascidin-743 in advanced pretreated soft tissue sarcoma patients. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grosso F, Dileo P, Sanfilippo R, Stacchiotti S, Bertulli R, Piovesan C, et al. Steroid premedication markedly reduces liver and bone marrow toxicity of trabectedin in advanced sarcoma. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42:1484–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Cesne A, Yovine A, Blay JY, Delaloge S, Maki RG, Misset JL, et al. A retrospective pooled analysis of trabectedin safety in 1132 patients with solid tumors treated in phase II clinical trials. Invest New Drugs 2012; 30:1193–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]