Abstract

This 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of low-dose (1.5–4.5 mg/day) and high-dose (6–12 mg/day) cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia (NCT00404573). The primary efficacy measure was change in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score, analyzed using a last observation carried forward approach. Other efficacy measures included the Clinical Global Impression-Severity (secondary) and PANSS subscales (additional). There were no significant differences between the two doses of cariprazine and placebo in PANSS total score change or any other efficacy parameter after multiplicity adjustment. However, low-dose cariprazine versus placebo showed significantly greater reductions in PANSS total (P=0.033) and PANSS negative (P=0.027) scores without multiplicity adjustment. Common treatment-emergent adverse events (incidence≥5% and twice that in the placebo group in either cariprazine dose group) were akathisia, restlessness, tremor, back pain, and extrapyramidal disorder. In this study, the overall cariprazine treatment effect was not statistically significant, but patients treated with low-dose cariprazine showed significantly greater improvement in schizophrenia symptoms relative to placebo-treated patients. Cariprazine was generally well tolerated. Results of this study suggest that cariprazine may be effective in treating schizophrenia and future research is warranted.

Keywords: antipsychotic, cariprazine, dopamine D3, schizophrenia

Introduction

Since their introduction in the 1990s, second-generation atypical antipsychotics have been considered the first-line treatment for schizophrenia. Atypical antipsychotics have similar efficacy to their first-generation predecessors and are thought to be associated with a lower propensity to induce extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), including tardive dyskinesia (Ban, 2007; Kane and Correll, 2010; Nasrallah et al., 2011).

Despite these advantages, their use is encumbered by metabolic issues, sedation, hypotension, weight gain, and limited efficacy, particularly negative symptoms and cognitive impairment (Kapur and Mamo, 2003; Lieberman et al., 2005; Kirkpatrick et al., 2006; Stroup et al., 2006; Keefe et al., 2007; Crossley et al., 2010; Tandon et al., 2010). During phase I of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study (Lieberman et al., 2005), antipsychotic discontinuation rates of 64–82% were reported because of the lack of efficacy, intolerable side effects, and other reasons. Therefore, new treatments with novel mechanisms of action may aid in improving the pharmacotherapeutic management of schizophrenia.

Cariprazine, a potent dopamine D3 and D2 receptor partial agonist with preferential binding to D3 receptors, is approved by the FDA for the treatment of schizophrenia and manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder; it is also in development for the treatment of bipolar depression and the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. The pharmacological profile of cariprazine is distinct from that of other antipsychotics in that it has an almost 10-fold greater affinity for D3 than D2 receptors in vitro (Kiss et al., 2010), and has high and balanced in-vivo occupancy of both D2 and D3 receptors in rats (Kiss et al., 2012) and humans (Slifstein et al., 2013). Although blockade of the dopamine D2 receptor is thought to be necessary for antipsychotic activity (Nord and Farde, 2011), affinity for additional neuroreceptors may enhance antipsychotic effects and further differentiate antipsychotics in terms of efficacy and tolerability. The dopamine D3 receptor is thought to be important in modulating mood and cognition and has emerged as a potential target for antipsychotic drug treatment (Gurevich and Joyce, 1999; Joyce and Millan, 2005; Laszy et al., 2005; Sokoloff et al., 2006).

Studies in animal models have shown that cariprazine confers dopamine D3 receptor-mediated cognitive-enhancing and antidepressant-like effects (Duman et al., 2012; Zimnisky et al., 2013). These results, together with potentially favorable pharmacological and preclinical efficacy data (Kiss et al., 2010; Gyertyán et al., 2011; Papp et al., 2014), led to this proof-of-concept, dose-range study evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.

Methods

Study design

This was a 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose, proof-of-concept study of 1.5–4.5 and 6–12 mg/day cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia (NCT00404573). Patients were enrolled at 34 US study centers; the study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each study center. ICH-E6 Good Clinical Practice guidelines were followed, and all patients provided written informed consent.

The study consisted of a no drug washout/screening period of up to 7 days, followed by 6 weeks of double-bind treatment and a 4-week safety follow-up period. Eligible patients were randomized (1 : 1 : 1) to receive placebo, low-dose cariprazine (1.5–4.5 mg/day), or high-dose cariprazine (6–12 mg/day) for the 6-week double-blind treatment period. Cariprazine dosing was once daily and was initiated at 1.5 mg/day for all patients. Dose adjustments were based on investigator judgment of response and tolerability. In the low-dose group, cariprazine could be uptitrated to 3 mg starting on Day 3, and to a maximum dose of 4.5 mg starting on Day 5. In the high-dose group, cariprazine dosage could be increased to 3 mg starting on Day 3, 6 mg starting on Day 5, 9 mg starting on Day 7, and to a maximum dose of 12 mg by Day 9. In patients with tolerability issues, reduction to a previous dose or a drug holiday of 1–2 days was allowed.

Patients were hospitalized during washout/screening and remained hospitalized for a minimum of 21 days after randomization to double-blind treatment; after 21 days, patients with a Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S; Guy, 1976b) score of 3 or lower and no significant risk for suicide or violent behavior could be discharged. Patients could be rehospitalized if their condition deteriorated.

Patients

Male or female patients (18–65 years of age) were eligible for inclusion if they met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. – text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for schizophrenia on the basis of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR. Patients had a schizophrenia diagnosis for 1 year or longer, with a current psychotic episode less than 4 weeks in duration and at least one other psychotic episode in the past year that required hospitalization or change in antipsychotic medication. At both screening and randomization, all patients had a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987, 1991) total score of 80–120 (inclusive), a score of 4 or higher on either the PANSS delusions item or the hallucinatory behavior item, a score of 4 or higher on either the PANSS conceptual disorganization item or the suspiciousness/persecution item, and a CGI-S score of 4 or higher.

Patients were excluded if they were in their first episode of psychosis, or if had they been diagnosed with schizoaffective, bipolar, or Axis II DSM-IV-TR disorders of sufficient severity to interfere with study participation. Additional exclusion criteria included alcohol or substance abuse or dependence within the past 3 months, or suicidal or homicidal intent within the past 2 years. Typical medical (e.g. uncontrolled medical illness; physical, laboratory, or ECG abnormalities; pregnant/breastfeeding women; BMI<18 or >40) and treatment-related (past/current use of certain psychotropic medications/treatment nonresponse to ≥2 marketed antipsychotics of adequate dose/duration) exclusions were also applied.

Medications with psychotropic activity were not allowed, with the following exceptions: lorazepam for control of agitation, irritability, hostility, or restlessness; zolpidem, zaleplon, chloral hydrate, or eszopiclone for insomnia; and diphenhydramine, benztropine, or propranolol for EPS.

Outcome measures

Efficacy measures were assessed as follows: PANSS was administered at screening (Week −1), baseline (Week 0), and all double-blind study visits (Weeks 1–6); CGI-S at Weeks 0–6; and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement at Weeks 1–6 (Guy, 1976b). PANSS was administered by an experienced clinician or trained psychiatric rater with expertise in the assessment of patients with schizophrenia; the CGI-S assessment was made by a psychiatrist.

Safety assessments included adverse event (AE) assessment (recorded at every visit), physical examination, clinical laboratory tests, vital sign assessments, 12-lead ECG (per analysis by central ECG interpretation laboratory), and administration of EPS scales [Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (Guy, 1976a), Barnes Akathisia Scale Items 1–3 (Barnes, 1989), and Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS; Simpson and Angus, 1970)]. Treatment-emergent parkinsonism was defined as an SAS score of 3 or lower at baseline and greater than 3 at any postbaseline assessment; treatment-emergent akathisia was defined as Barnes Akathisia Scale score of 2 or lower at baseline and greater than 2 at any postbaseline assessment. Ophthalmologic examination of the cornea and lens was performed at five designated sites on all randomized patients at baseline and at the end of the double-blind treatment (Week 6 or early termination) and safety follow-up phases.

Statistical methods

The safety population consisted of patients who received at least one dose of study medication; the intent-to-treat population consisted of all patients in the safety population who also had one or more postbaseline PANSS total score assessment. Demographic and baseline characteristics were compared among groups using a two-way analysis of variance model with treatment group and study center as factors for continuous variables and the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for categorical variables.

The primary efficacy parameter was PANSS total score change from baseline to Week 6. Between-group comparisons used an analysis of covariance model, with treatment group and study center as factors and baseline PANSS total score as a covariate. The missing postbaseline values were imputed using the last observation carried forward approach. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at a 5% level of significance. To control overall type I error rate, a sequential, stepwise multiple-comparison procedure was used. First, an overall F-test comparing the three treatment groups was performed at the 5% level of significance, followed by pairwise comparisons between each cariprazine dose group and placebo. A pairwise comparison was considered statistically significant with multiplicity adjustment only if both the overall and the respective pairwise comparisons were statistically significant. Two sensitivity analyses based on observed cases were performed using an analysis of covariance model and a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM). For MMRM, treatment group, study center, visit, and the treatment group-by-visit interaction were fixed effects and baseline value was a covariate. The secondary efficacy parameter, change from baseline to Week 6 in CGI-S score, was analyzed using similar methods.

Clinical Global Impression-Improvement analysis was carried out using an analysis of variance model with treatment group and study center as factors; PANSS response (≥20% improvement from baseline in PANSS total score) was analyzed using a logistic regression model with treatment group and baseline PANSS score as explanatory variables.

Safety parameters were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patient characteristics and disposition

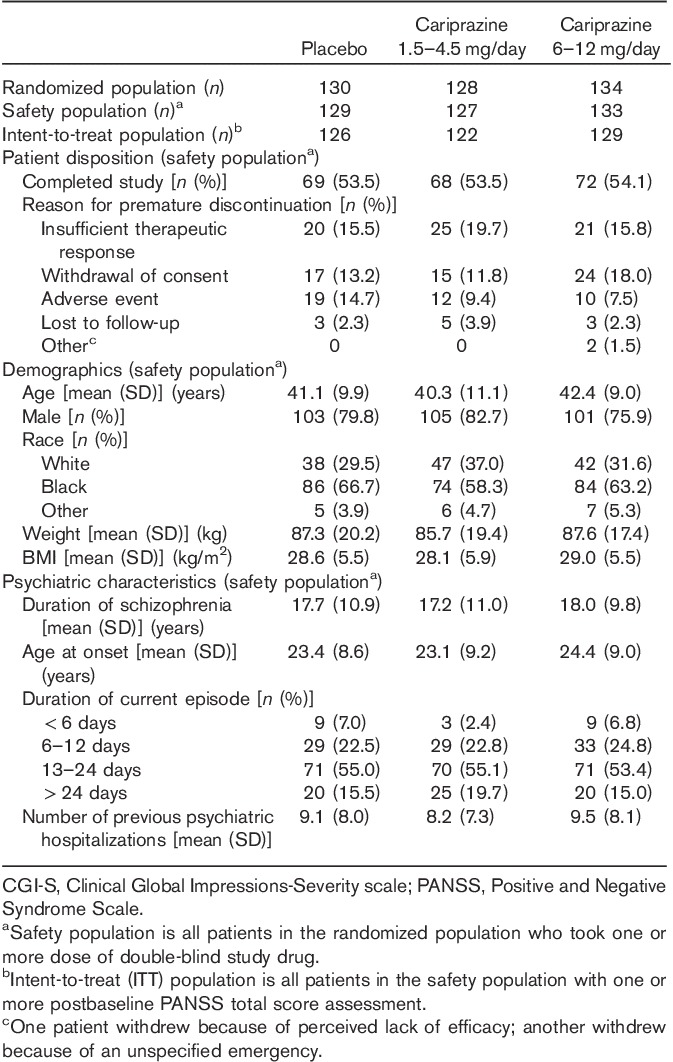

Of the 392 patients who were randomized, ∼54% completed the study. Completion rates were similar among the three treatment groups, with insufficient therapeutic response, withdrawal of consent, and AEs as the most frequent (>10%) reasons for premature discontinuation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

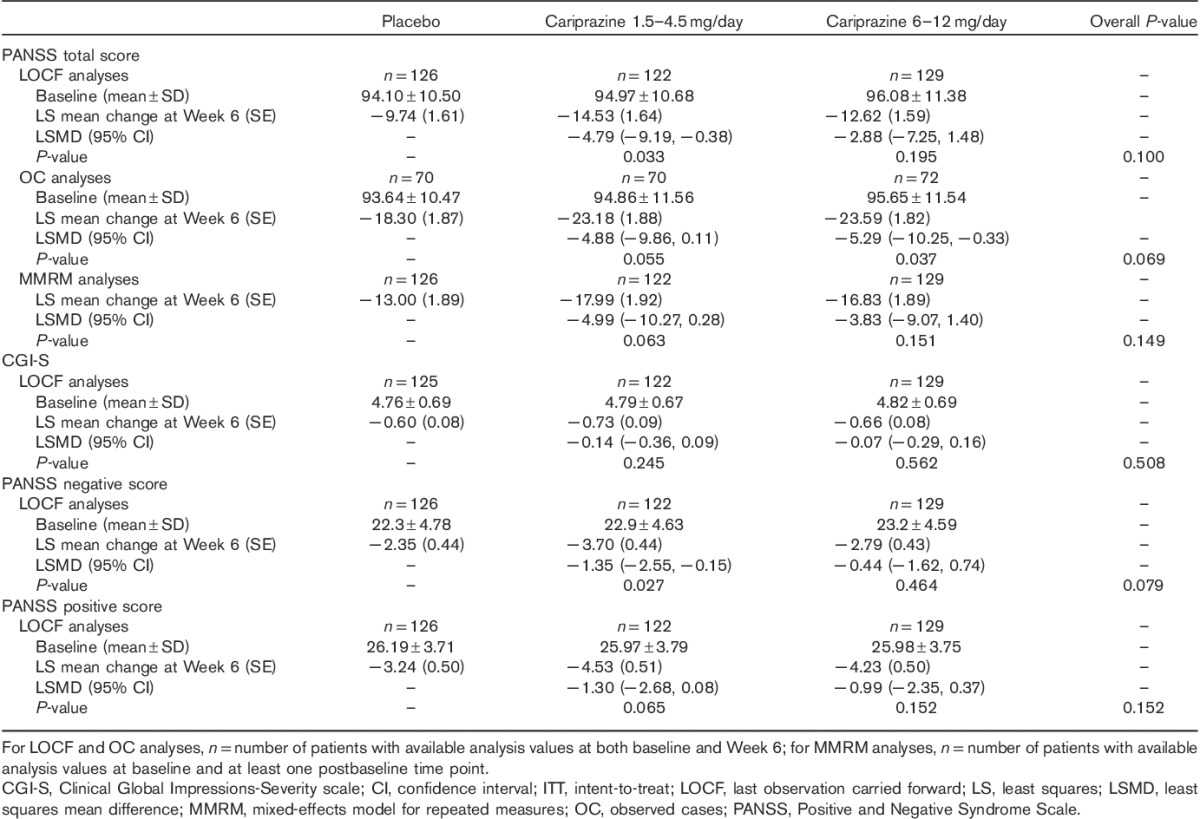

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were similar among the treatment groups (Table 1). The mean baseline PANSS (Leucht et al., 2005) and CGI-S scores (Guy, 1976b) indicate a moderately to severely ill patient population (Table 2).

Table 2.

PANSS and CGI-S score changes from baseline to Week 6 (ITT population)

Efficacy

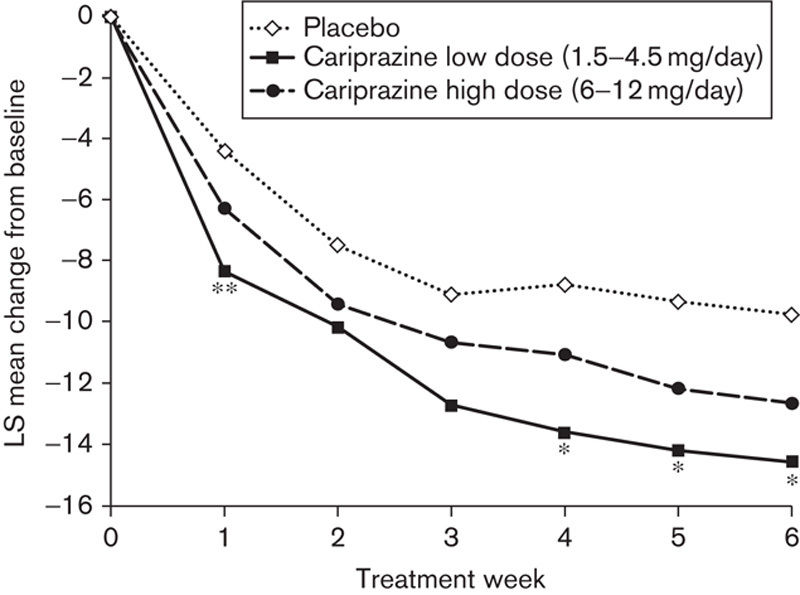

On the primary efficacy measure, the mean change in PANSS total score from baseline to Week 6, the overall P-value comparing the three treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.100). Pairwise comparison without adjustment for multiple comparisons between the low-dose cariprazine group (1.5–4.5 mg/day) and placebo was significant (P=0.033; Table 2). No significant difference was found in the pairwise comparison of the PANSS total score change of 6–12 mg/day cariprazine and placebo (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pairwise comparisons: PANSS total score change from baseline to Week 6 (intent-to-treat population; last observation carried forward). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus placebo. LS, least squares; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Overall and pairwise comparisons between cariprazine and placebo on the secondary efficacy measure, the CGI-S, were not significantly different on using the last observation carried forward approach (Table 2) or on sensitivity analyses (observed case or MMRM, not shown).

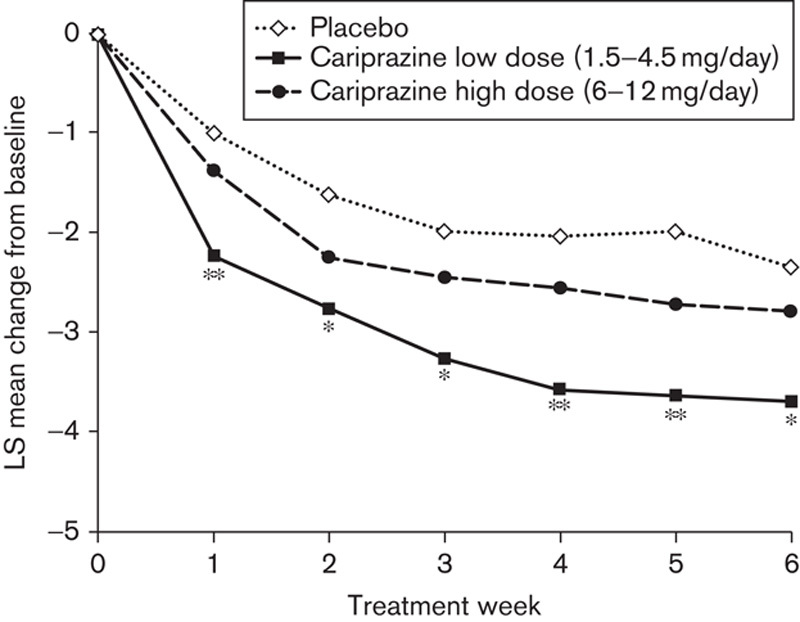

Patients treated with 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine experienced significantly greater improvement (without multiplicity adjustment) than the placebo group in PANSS negative scores from baseline to Week 6, but the overall P-value for the cariprazine treatment effect was not statistically significant (Table 2). Separation from placebo in the 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine group was observed by Week 1 and continued throughout each week of the double-blind treatment phase (Fig. 2). Pairwise comparison between 6–12 mg/day cariprazine and placebo in PANSS negative score changes at Week 6 was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Pairwise comparison: PANSS negative score change from baseline to Week 6 (intent-to-treat population; last observation carried forward). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus placebo. LS, least squares; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Improvement from baseline in PANSS positive score in cariprazine-treated patients (overall and pairwise comparisons) was not significantly different compared with placebo (Table 2). There was a numerically higher response rate (≥20% improvement from baseline in PANSS total score) at Week 6 for cariprazine patients (1.5–4.5 mg/day: 43%, and 6–12 mg/day: 35%) versus placebo (31%), but the difference did not reach statistical significance in the overall or the pairwise comparisons with placebo. No statistically significant differences between cariprazine groups and placebo were observed in any other additional efficacy parameter.

Safety

Exposure

The mean treatment duration was 30.6 days for placebo, and 30.3 and 29.8 days for 1.5–4.5 and 6–12 mg/day cariprazine groups, respectively; the overall mean daily doses were 3.83 and 8.70 mg/day for 1.5–4.5 and 6–12 mg/day cariprazine groups, respectively.

Adverse events

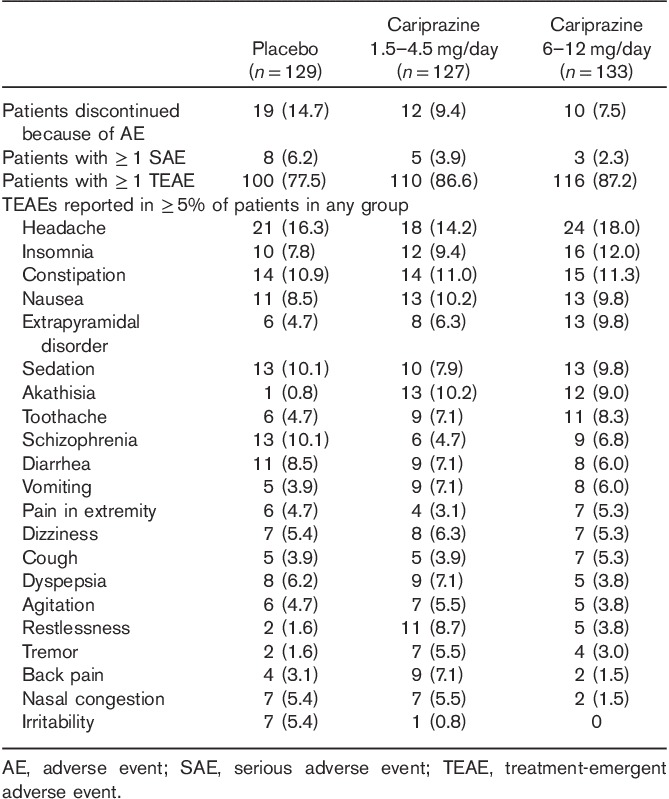

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in similar percentages of patients in all three treatment groups (Table 3); most TEAEs (∼94, 98, and 98% in the placebo, low-dose, and high-dose cariprazine groups, respectively) were mild to moderate in intensity. The only TEAEs that were reported during double-blind treatment in at least 5% of the patients in either cariprazine group and with an incidence of at least twice the rate in the placebo group were akathisia (both groups), restlessness (1.5–4.5 mg/day), tremor (1.5–4.5 mg/day), back pain (1.5–4.5 mg/day), and extrapyramidal disorder (6–12 mg/day). More patients discontinued because of AEs in the placebo group relative to the cariprazine groups (Table 3); the most frequent (≥2%) AEs contributing to discontinuation in the cariprazine groups were schizophrenia (placebo, 5.4%; 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine, 3.9%; 6–12 mg/day cariprazine, 3.8%) and akathisia (placebo, 0; 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine, 0.8%; 6–12 mg/day cariprazine, 2.3%).

Table 3.

Adverse events during the double-blind treatment period (safety population)

Serious AEs were reported in 16 patients during double-blind treatment (Table 3); of these, nine were considered to be possibly related to the study drug: three placebo (schizophrenia, status epilepticus, and psychotic disorder in one patient each), four 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine (schizophrenia in two patients, and seizures and hyponatremia in one patient each), and two 6–12 mg/day cariprazine (aggression/physically threatening and violent behavior, suicidal ideation/schizophrenia in one patient each).

During the safety follow-up phase, the only TEAE that was reported in at least 5% of the patients in any treatment group was schizophrenia. A total of 26 patients reported serious AEs during the safety follow-up phase, the most common of which were schizophrenia (placebo, 5.4%; 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine, 0.8%; 6–12 mg/day cariprazine, 5.3%), psychotic disorder (placebo, 3.1%; 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine, 0.8%; 6–12 mg/day cariprazine, 0), and aggression (placebo, 0; 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine, 0; 6–12 mg/day cariprazine, 1.5%). No deaths occurred during the study.

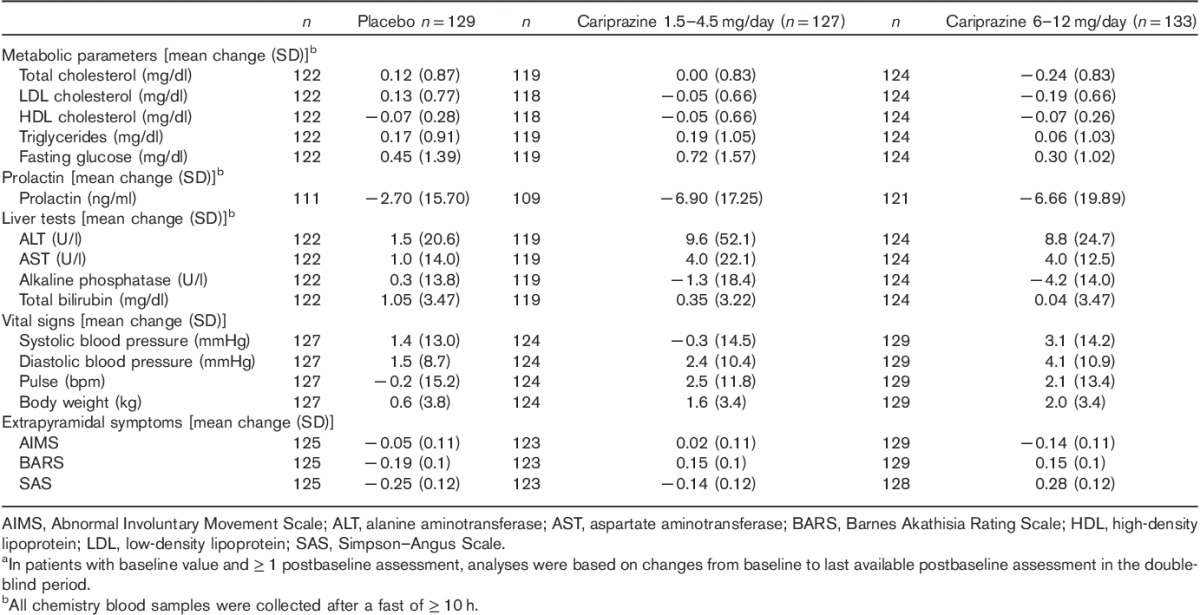

Laboratory parameters, vital signs, ECG, and ophthalmologic assessments

The mean changes from baseline to the end of study in metabolic parameters were generally similar across treatment groups (Table 4). Prolactin levels decreased in all three treatment groups. There were greater mean increases in alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels in the cariprazine groups compared with placebo; however, there was no evidence of a trend toward increased mean levels of total bilirubin or alkaline phosphate. No patient met Hy’s Law criteria [alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase at least three times the upper limit of normal (ULN), concurrent with total bilirubin at least two times the ULN and alkaline phosphatase less than two times the ULN].

Table 4.

Mean changes in safety parameters during the double-blind treatment period (safety population)a

Slightly greater mean increases in blood pressure and body weight occurred in the cariprazine groups compared with placebo, with greater increases in blood pressure and weight in the high-dose group versus the low-dose cariprazine group. Incidences of orthostatic hypotension were slightly higher in the high-dose cariprazine group (18.8%) relative to the low-dose group (13.4%) and placebo (14.7%).

No patient in any treatment group had QTcB, or QTcF interval greater than 500 ms; slight increases in ventricular heart rate were observed in the cariprazine treatment groups relative to placebo.

The mean changes in ophthalmologic parameters were small and similar between groups.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

The mean changes in EPS scores were higher in the cariprazine groups relative to placebo (Table 4). Akathisia was the most common EPS-related TEAE (placebo, 2.3%; 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine, 13.4%; 6–12 mg/day cariprazine, 15%). Most (>95%) EPS-related TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity, and no patient experienced tardive dyskinesia or neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Movement disorder-related TEAEs resulted in five discontinuations (one patient in the 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine group and four in the 6–12 mg/day cariprazine group).

The incidence of treatment-emergent parkinsonism (SAS score>3) was 3.9% in the placebo group, 9.4% in the 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine group, and 9.8% in the 6–12 mg/day cariprazine group. Use of antiparkinson medications was higher in cariprazine-treated patients (22 and 28.6% in the low-dose and high-dose cariprazine groups, respectively) than in placebo (15.5%), as was use of β-blocking agents (9.4 and 9.8% in 1.5–4.5 and 6–12 mg cariprazine groups, respectively, and 1.6% in placebo). The use of lorazepam for agitation and restlessness was ∼84, 92, and 91% in the placebo, and low-dose and high-dose cariprazine groups, respectively.

Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study, there was no significant difference in the overall comparison between cariprazine and placebo in the mean change from baseline to Week 6 in PANSS total score (the primary efficacy assessment), or in any of the other efficacy parameters tested.

Using pairwise comparisons (without multiplicity adjustment), it was found that PANSS total and PANSS negative scores significantly improved in the 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine group relative to the placebo group; improvement relative to placebo in PANSS negative scores occurred by Week 1 and persisted to the end of the study. There were no significant differences on pairwise comparisons between high-dose (6–12 mg/day) cariprazine and placebo groups in the PANSS total, positive, or negative score, or in any other efficacy parameter tested.

Cariprazine was generally well tolerated in this study at doses of up to 12 mg/day, with no apparent dose–response relationship between the cariprazine groups in safety parameters, with the possible exception of blood pressure, sedation, EPS, headache, and insomnia. Cariprazine treatment was not associated with clinically meaningful changes in metabolic parameters, elevated prolactin levels, or prolonged QTc intervals. Most TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity, and there were no apparent differences in severity among cariprazine doses. Movement disorder-related TEAEs (e.g. extrapyramidal disorder, akathisia, dystonia, and tremor) were reported more frequently in the cariprazine groups, but most events were mild to moderate in severity and discontinuations because of EPS symptoms were infrequent.

Although this study did not meet the primary efficacy objective, the significant advantage in the low-dose group relative to the placebo group suggested that further cariprazine studies for the treatment of schizophrenia are warranted. Therefore, three subsequent phase II and III trials followed this proof-of-concept study to further evaluate cariprazine in the treatment of schizophrenia (Durgam et al., 2014, 2015; Kane et al., 2015). In the three studies, cariprazine showed significantly greater improvement compared with placebo on most efficacy measures, including PANSS total, PANSS positive, and PANSS negative scores, at doses of 1.5, 3, 4.5, and 6 mg/day in the fixed-dose studies (Durgam et al., 2014, 2015), and 3–6 and 6–9 mg/day in the flexible-dose study (Kane et al., 2015). The lack of a statistically significant improvement in this study in the high-dose cariprazine group is surprising in light of the efficacy seen in the low-dose cariprazine group. Robust improvement was observed in patients treated with higher doses of cariprazine (6–9 mg/day) in later studies (Durgam et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015), but comparisons between these studies and the high-dose group in this study are difficult as most (84%) patients in this group were taking 12 mg/day cariprazine by the end of the study, a higher dose than was permitted in any of the subsequent studies.

The incongruity between the results of this trial and the subsequent phase 3 studies is perplexing given the similarity in their designs. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were almost identical, with similar baseline characteristics, demographics, and disease histories across the patient populations. The mean baseline PANSS and CGI-S scores were also indicative of similar levels of illness. One notable exception was that this study was conducted only at study centers in the USA, whereas subsequent trials were conducted at both US and non-US study centers. Increasing placebo response and decreasing treatment effect over time have been observed in schizophrenia trials conducted in the USA (Khin et al., 2012); however, without an active comparator, we have no way of knowing whether this study failed because of a high placebo response.

Conclusion

In this proof-of-concept, dose-range study, the overall cariprazine treatment effect did not meet statistical significance, although the 1.5–4.5 mg/day cariprazine group demonstrated significant improvements over placebo on the primary efficacy parameter without multiplicity adjustment; differences in the 6–12 mg/day cariprazine group did not reach statistical significance relative to placebo. Cariprazine was generally well tolerated across the dose range tested.

Acknowledgements

Writing assistance and editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Jennifer Kaiser, PhD, and Paul Ferguson, MS, of Prescott Medical Communications Group, Chicago, Illinois, a contractor for Forest Research Institute (an Allergan affiliate).

This study was supported by funding from Forest Laboratories, LLC (an Allergan affiliate) and Gedeon Richter Plc. Forest Laboratories, LLC (an Allergan affiliate) and Gedeon Richter Plc. were involved in the study design, data collection (through contracted clinical investigator sites), analysis and interpretation of data, and the decision to present these results.

Conflicts of interest

Suresh Durgam acknowledges a potential conflict of interest as an employee of Forest Research Institute (an Allergan affiliate). Robert E. Litman acknowledges a potential conflict of interest as a member of the speaker’s bureau for Johnson & Johnson and Otsuka. Kelly Papadakis and Dayong Li acknowledge a potential conflict of interest as employees of Forest Research Institute (an Allergan affiliate) at the time of this study. György Németh and István Laszlovszky acknowledge a potential conflict of interest as employees of Gedeon Richter Plc.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – text revision, 4th Edition Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ban TA. (2007). Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 3:495–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TR. (1989). A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley NA, Constante M, McGuire P, Power P. (2010). Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 196:434–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Duric V, Banasr M, Adham N, Kiss B, Gyertyán I. (2012). Cariprazine exhibits dopamine D3 receptor-dependent antidepressant-like activity in the chronic unpredictable stress model of anhedonia. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:S84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, Migliore R, Ruth A, Németh G, Laszlovszky I. (2014). An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res 152:450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgam S, Cutler AJ, Lu K, Migliore R, Ruth A, Laszlovszky I, et al. (2015). Cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a fixed-dose, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich EV, Joyce JN. (1999). Distribution of dopamine D3 receptor expressing neurons in the human forebrain: comparison with D2 receptor expressing neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology 20:60–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. (1976a). The Abnormal Movement Scale ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. (1976b). The Clinician Global Severity and Impression scales ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gyertyán I, Kiss B, Sághy K, Laszy J, Szabó G, Szabados T, et al. (2011). Cariprazine (RGH-188), a potent D3/D2 dopamine receptor partial agonist, binds to dopamine D3 receptors in vivo and shows antipsychotic-like and procognitive effects in rodents. Neurochem Int 59:925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JN, Millan MJ. (2005). Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as therapeutic agents. Drug Discov Today 10:917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Correll CU. (2010). Past and present progress in the pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 71:1115–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, Lu K, Ruth A, Nagy K, et al. (2015). Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 35:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Mamo D. (2003). Half a century of antipsychotics and still a central role for dopamine D2 receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 27:1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Opler LA, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Fiszbein A, Gorelick A. (1991). SCID-PANSS: two-tier diagnostic system for psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry 32:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Bilder RM, Davis SM, Harvey PD, Palmer BW, Gold JM, et al. (2007). Neurocognitive effects of antipsychotic medications in patients with chronic schizophrenia in the CATIE Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:633–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khin NA, Chen YF, Yang Y, Yang P, Laughren TP. (2012). Exploratory analyses of efficacy data from schizophrenia trials in support of new drug applications submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Psychiatry 73:856–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Jr., Marder SR. (2006). The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 32:214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, Schmidt E, Laszlovszky I, Bugovics G, et al. (2010). Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 333:328–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss B, Horti F, Bobok A. (2012). Cariprazine, a D3/D2 dopamine receptor partial agonist antipsychotic, displays greater D3 receptor occupancy in vivo compared with other antipsychotics. Schizophr Res 136 (Suppl 1):S190. [Google Scholar]

- Laszy J, Laszlovszky I, Gyertyán I. (2005). Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists improve the learning performance in memory-impaired rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 179:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel RR. (2005). What does the PANSS mean? Schizophr Res 79:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. (2005). Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 353:1209–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah H, Tandon R, Keshavan M. (2011). Beyond the facts in schizophrenia: closing the gaps in diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 20:317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord M, Farde L. (2011). Antipsychotic occupancy of dopamine receptors in schizophrenia. CNS Neurosci Ther 17:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp M, Gruca P, Lasoń-Tyburkiewicz M, Adham N, Kiss B, Gyertyán I. (2014). Attenuation of anhedonia by cariprazine in the chronic mild stress model of depression. Behav Pharmacol 25:567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM, Angus JW. (1970). A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 212:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifstein M, Abi-Dargham A, D’Souza DC, RE C, Laszlovszky I, Durgam S, et al. (2013). Cariprazine demonstrates high dopamine D3 and D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: a clinical pet study with [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:S520. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Diaz J, Le Foll B, Guillin O, Leriche L, Bezard E, Gross C. (2006). The dopamine D3 receptor: a therapeutic target for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 5:25–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, et al. (2006). Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 163:611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. (2010). Schizophrenia, "just the facts" 5. Treatment and prevention. Past, present, and future. Schizophr Res 122:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimnisky R, Chang G, Gyertyán I, Kiss B, Adham N, Schmauss C. (2013). Cariprazine, a dopamine D(3)-receptor-preferring partial agonist, blocks phencyclidine-induced impairments of working memory, attention set-shifting, and recognition memory in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 226:91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]