Key clinical message

Cancer‐associated retinopathy (CAR) is a rare paraneoplastic visual syndrome. Its early detection may lead to the diagnosis of the causative malignancy. As many different types of malignancies are known to be associated with CAR, it is important that clinicians are aware of the phenomenon of CAR.

Keywords: Cancer, cancer associated retinopathy, colon, colorectal

Introduction

Paraneoplastic syndromes are a heterogeneous group of clinical disorders that arise due to an underlying neoplasm. By definition, these clinical symptoms are not directly related to physical effects of the neoplasm or its accompanying metastases, but are rather triggered by an alteration of the immune system (cross‐reactivity) or by secretion of functional hormones from the tumor. Symptoms therefore show a broad variety ranging from endocrine to neurologic, but may also involve any other system of the body.

Among paraneoplastic syndromes, visual disorders are extremely rare. Cancer‐associated retinopathy (CAR) (Table 1) is a paraneoplastic syndrome mediated by autoimmune antibodies directed against proteins in retinal photoreceptor cells 1. The disease was first described in 1976. Recently, extraocular cancer was identified as the source of autoimmune antibody formation in patients with CAR. The autoimmune reaction itself leads to retinal photoreceptor cell death 2, 3, 4. No specific test exists to confirm CAR what makes its diagnosis quite difficult. Typically, loss of vision develops over months and can precede the diagnosis of the underlying malignancy. The percentage of patients presenting with visual symptoms prior to cancer diagnosis seems to be relatively unclear. In one study of Adamus et al. 6, only eight of 209 patients had visual symptoms before cancer diagnosis, whereas Rahimy and Sarraf reported preceding symptoms in almost half of patients with CAR 8. The diagnosis of CAR is established if a combination of different characteristic features is present. Often visual field defects, abnormal electroretinograms and serum autoantibodies can be found 5. Different autoantibodies have been investigated and identified in patients with CAR. Only about 65% of CAR patients present antiretinal antibodies and the most frequently detected are – in descending order – against α‐enolase (~30% of patients), transducin (~17%), carbonic anhydrase II (~14%), and recoverin (~10%) 6. Because CAR is such a rare disease, there are no statistical data on its incidence or prevalence. According to the work by Adamus et al. 6, average age of presenting symptoms is 65 years and the disease affects more women than men with a ratio of 2:1. Since the first review in 2003, which included 55 cases, the number of CAR has significantly increased 7. The vast majority of tumors associated with CAR are small‐cell lung cancer and gynecological malignancies 6, 10. Case reports exist for other solid tumors including non‐small‐cell lung, bladder, prostate, pancreatic, small bowel, thymus, and thyroid cancer 8. The association of CAR with colon cancer has also been described, but seems to be extremely rare. In the current literature, there are only two reported cases of colon cancer patients suffering from CAR. These two reports have certain interesting similarities with the patient we are reporting 9, 10.

Table 1.

Overview: Cancer types, autoantibodies detected, treatment and outcomes for CAR

| Author Year | Malignancy | Symptoms | Autoantibodies | Therapy | Course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Thirkill CE 1989 13 |

Small‐cell lung cancer |

Progressive loss of vision in both eyes 20/50 OD 20/100 OS |

No AB reported | Plasmapheresis | No improvement |

|

Ohnishi Y 1993 14 |

Small‐cell lung cancer | Right eye with ring scotomas | Recoverin Arrestin | Prednisone | Mild improved vision |

|

Adamus G. 1998 15 |

Endometrial cancer | Loss of color vision in OS and blurring vision in OD. Visual acuity was 20/70 OD and counting fingers OS | Recoverin | Methylprednisolone and immunomodulator drug | Visual acuity stabilized at hand motions |

|

Whitcup SM 1998 16 |

Benign Warthin tumor of the left parotid gland | Progressive vision loss in both eyes | Recoverin | Systemic prednisone treatment | Visual acuity diminished to no light perception |

|

Yoon YH 1999 17 |

Ovarian cancer | Sense of darkness in both eyes 20/25 OD 20/30 OS | α‐enolase | Prednisolone p.o. | Visual acuity diminished to movement perception |

|

Guy J 1999 18 |

Pat. 1 Adenocarcinoma of the lung Pat. 2 Adenocarcinoma of the cervix Pat. 3 Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas |

Pat. 1 Rapid progressive visual loss Pat. 2 Blindness Pat. 3 Loss of vision in the right eye |

Pat. 1 enolase Pat. 2 recoverin Pat. 3 enolase |

Immunoglobulin i.v. |

Pat. 1 Marked visual field improvement, visual acuity maintained at 20/50 OD and 20/40 OS. Pat. 2 No improvements Pat. 3 Improvements in visual field defects |

|

Jacobsen D 2000 9 |

Adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon | Progressive visual glare in both eyes | No anti‐retinal antibodies | No CAR‐specific therapy | Improved retinal function |

|

Raghunath A 2010 19 |

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the fallopian tube | Progressive worsening of vision in both eyes. Best visual acuity 20/25 OD, 20/60 OS | Carbonic anhydrase II α‐enolase | No CAR‐specific therapy | Visual acuity in follow up 20/30 OD, 20/40 OS |

|

Cybulska P 2011 20 |

Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium | Dimmed vision in both eyes with best corrected visual acuity 20/150 in both eyes | No AB reported | Five sessions plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin plus intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection OS | Vision deteriorated to light perception only |

|

Huynh N 2012 21 |

Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the lung | Decreased vision, photopsias and nyctalopia in both eyes | α‐enolase | Serial intravitreal injections of triamcinolone | Vision preserved at 20/40 OD and 20/32 OS |

|

Chao D 2013 10 |

Colon adenocarcinoma |

Progressive bilateral constriction of visual fields 20/60 OD 20/25 OS |

α‐enolase α‐transducin |

No CAR‐specific therapy |

Visual acuity improved 20/30 OS 20/25 OS |

|

Ogra S 2013 22 |

Carcinoid tumor of the small bowel | Progressive blurring of vision and nyctalopia in both eyes | Carbonic anhydrase II α‐enolase | n/a | Pat. died 1 month after diagnosis of CAR from small bowel obstruction |

|

Michiyuki S 2014 23 |

Small‐cell lung carcinoma | Progressive central vision loss OD and bilateral neuroretinits | Recoverin α‐enolase CRMP‐5 | Prednisolone oral | Optic disk swelling disappeared |

|

Turaka K 2014 24 |

Immature teratoma of the ovary | Diminished vision in both eyes | Arrestin | Methylprednisolone i.v. along with i.v. immunoglobulins and rituximab, followed by systemic prednisolone and biweekly intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab for 3 months | Each eye with improvement in color vision |

|

Nakamura T 2015 25 |

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung |

Rapid visual disorder in the dark, photophobia and impaired visual field. Visual acuities for both eyes 20/20 |

No anti‐retinal antibodies | No CAR‐specific therapy | Visual function was stable |

|

Javaid Z 2015 26 |

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | Unilateral blurred vision, disturbance in color and night vision and central sparing with residual VF islands of OS | No AB reported | Periocular steroid injections | Visual acuity remained stable |

Case Presentation

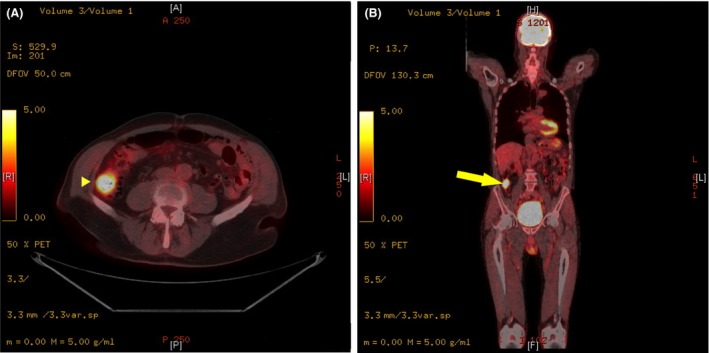

We present the case of a 76‐year‐old man who experienced progressive loss of vision of both eyes over a time period of 18 months. The patient was otherwise healthy, had no regular medication and is a nonsmoker. The family history for retinal disorders was negative. During the 18 months period, the patient was sent to several ophthalmologists, but no definitive diagnosis could be established. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head did not reveal retrobulbar tumor and all the intraorbital structures as well as the chiasma opticum appeared to be normal. Finally, ophthalmologic evaluation at our institution was highly suspicious for CAR. The best corrected visual acuity was 0.8 for oculus dexter (−0.25/−0.75/176°) and 0.4 for oculus sinister (−1.25/150°). Full‐field electroretinogram (ERG) did not show any amplitudes in A‐ and B‐waves. Multifocal ERG revealed markedly attenuated bilateral responses in the central and paracentral region. Visually evoked potentials (VEP) showed substantially delayed amplitude and latency periods for both eyes and in Flicker 30 Hz ERG responses were also substantially reduced. Examination of the field of vision for both eyes showed central scotomas. The patient had no other eye or neurological symptoms. Empiric steroid therapy was instituted with 20 mg prednisone per day and antiretinal antibody analysis was performed (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, United States and MVZ Labor Volkmann, Karlsruhe, Germany). Western blot was negative for recoverin, α‐enolase, transducin, and carbonic andydrase II antibodies. Subsequent positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET‐CT) revealed a tumor mass in the ascending colon (Figs 1A and B). Colonoscopy showed an ulcerated adenocarcinoma occluding one‐third of the bowels circumference, with a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in normal range. The patient reported no weight loss, changes in bowel habits, melena, or hematochezia. In addition, family history for colon cancer was negative. Laparoscopic right‐sided hemicolectomy was performed and histological diagnosis confirmed an adenocarcinoma pT1, pN0 (0/12). On postoperative day two, emergency laparotomy was necessary due to an acute abdomen. Intraoperatively complete ischemia of the remaining colon was detected and subtotal colectomy with creation of an ileostomy had to be performed. Immediately after operation, CT scan angiography was carried out to exclude thrombotic events elsewhere. Tests for other diseases combined with coagulation disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus and anti‐phospholipid antibody syndrome were negative. Histology demonstrated acute ischemic enterocolitis on the basis of thrombosis of the arteries. Further recovery was uneventful. Finally, empiric steroid therapy was continued with 50 mg/day. Despite this therapy, the loss of vision was progressive. Three months after operation best corrected visual acuity was 0.6 for oculus dexter and 0.4 for oculus sinister. Full‐field ERG showed no photopic or scotopic response. Multifocal ERG did not show any answer. Examination of the field of vision for the right eye showed an absolute scotoma central, infero‐nasal and superior, and for the left eye, a concentric absolute scotoma, meaning that the patient has lost almost all his visual acuity.

Figure 1.

Yellow arrow: Mass in the ascending colon, diameter of 3.5 cm, with significantly increased glucose metabolism of SUVmax 8.9.

Discussion

The current literature reveals only two other reports about CAR in association with colon cancer. These two patients presented with similar characteristics 9, 10. As in these two cases, our patient neither had any gastrointestinal complaints nor colon cancer was diagnosed prior to CAR. Moreover, anti‐retinal antibodies could not be detected with western blot, a finding also described by Jacobsen et al. They instead detected antibodies with immunocytochemical analysis, a method not available on a commercial basis in Europe. The patient's serum in the report by Chao et al. was positive for α‐enolase and transducin, but not for recoverin. One should be aware that patients with CAR tend to have a broad spectrum of anti‐retinal antibodies often with up to six different antibodies in western blot 11. Furthermore, we have to take into account that in up to 35% of CAR patients‐specific antibodies cannot be detected 6, 9. Our patient was diagnosed with stage I colon cancer and therefore no adjuvant treatment was necessary. Chao et al. and Jacobsen et al. reported a stage II and Duke C adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon, respectively. Both patients did receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Eight months after treatment anti‐retinal antibodies could not be detected neither by western blot nor by immunocytochemistry in the patient reported by Jacobsen et al. and visual symptoms almost completely resolved. Chao et al. do not state if cancer treatment could improve visual symptoms and if the level of anti‐retinal antibodies decreased after operation. Whether treatment of the causative cancer may delay or even stop progressive loss of vision is unclear.

Adamus et al. reported a case of a patient suffering from small‐cell lung cancer in whom cancer treatment decreased the amount of antibodies, probably as a result of radiation therapy. As soon as the host's immune system did recover, antibody levels again began to raise. The authors therefore speculate that cancer treatment itself does not improve vision 12.

Heckenlively and Ferreyra reported that prednisone can stabilize loss of vision in CAR patients, but has to be administered over a period of at least 1 year 11. In the review by Rahimy and Sarraf, the authors described different treatment attempts showing mixed results. They reported on cases in which a combination of systemic corticosteroids either with plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin administration, or immunomodulatory therapies was used 8. These sometimes promising results have to be taken with caution because the sample size varies between one and six patients, all suffering from different types of malignancies. It should be clearly stated that currently no evidence for the management of CAR is existing. Immunosuppressive therapy is the main element in treatment of CAR but visual prognosis remains poor and loss of vision might be inevitable 8.

In summary, early detection of paraneoplastic visual syndromes may lead to the diagnosis of the causative malignancy. Therefore, in case of unusual visual disorders, suspicion of an underlying malignancy should arise. Due to the simple fact that malignancies can occur in different organs, we strongly encourage that every clinician should be aware of the phenomenon of cancer‐related retinopathy.

All three authors contributed equally to conception, design, writing, revising, and final approval of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Clinical Case Reports 2016; 4(2): 171–176

References

- 1. Adamus, G. , Machnicki M., and Seigel G. M.. 1997. Apoptotic retinal cell death induced by antirecoverin autoantibodies of cancer‐associated retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 38:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sawyer, R. A. , Selhorst J. B., Zimmerman L. E., and Hoyt W. F.. 1976. Blindness caused by photoreceptor degeneration as a remote effect of cancer. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 81:606–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forooghian, F. , Macdonald I. M., Heckenlively J. R., Héon E., Gordon L. K., Hooks J. J., et al. 2008. The need for standardization of antiretinal antibody detection and measurement. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 146:489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adamus, G. 2003. Autoantibody‐induced apoptosis as a possible mechanism of autoimmune retinopathy. Autoimmun. Rev. 2:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobson, D. M. , Thirkill C. E., and Tipping S. J.. 1990. A clinical triad to diagnose paraneoplastic retinopathy. Ann. Neurol. 28:162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adamus, G. 2009. Autoantibody targets and their cancer relationship in the pathogenicity of paraneoplastic retinopathy. Autoimmun. Rev. 8:410–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chan, J. W. , D. Chao , W.‐C. Chen , C. E. Thirkill , and A. G. Lee . Paraneoplastic retinopathies and optic neuropathies. Surv. Ophthalmol. 48:12–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rahimy, E. , and D. Sarraf . 2013. Paraneoplastic and non‐paraneoplastic retinopathy and optic neuropathy: evaluation and management. Surv. Ophthalmol. 58:430–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobson, D. M. , and Adamus G.. 2001. Retinal anti‐bipolar cell antibodies in a patient with paraneoplastic retinopathy and colon carcinoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 131:806–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chao, D. , Chen W.‐C., Thirkill C. E., and Lee A. G.. 2013. Paraneoplastic optic neuropathy and retinopathy associated with colon adenocarcinoma. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 48:e116–e120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heckenlively, J. R. , and Ferreyra H. A.. 2008. Autoimmune retinopathy: a review and summary. Semin. Immunopathol. 30:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adamus, G. , Ren G., and Weleber R. G.. 2004. Autoantibodies against retinal proteins in paraneoplastic and autoimmune retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thirkill, C. E. , FitzGerald P., Sergott R. C., Roth A. M., Tyler N. K., and Keltner J. L.. 1989. Cancer‐associated retinopathy (CAR syndrome) with antibodies reacting with retinal, optic‐nerve, and cancer cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:1589–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohnishi, Y. , Ohara S., Sakamoto T., Kohno T., and Nakao F.. 1993. Cancer‐associated retinopathy with retinal phlebitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 77:795–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adamus, G. , Amundson D., MacKay C., and Gouras P.. 1998. Long‐term persistence of antirecoverin antibodies in endometrial cancer‐associated retinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 116:251–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whitcup, S. M. , Vistica B. P., Milam A. H., Nussenblatt R. B., and Gery I.. 1998. Recoverin‐associated retinopathy: a clinically and immunologically distinctive disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 126:230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoon, Y. H. , Cho E. H., Sohn J., and Thirkill C. E.. 1999. An unusual type of cancer‐associated retinopathy in a patient with ovarian cancer. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 13:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guy, J. 1999. Treatment of paraneoplastic visual loss with intravenous immunoglobulin. Arch. Ophthalmol. 117:471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raghunath, A. , Adamus G., Bodurka D. C., Liu J., and Schiffman J. S.. 2010. Cancer‐associated retinopathy in neuroendocrine carcinoma of the fallopian tube. J. Neuroophthalmol. 30:252–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cybulska, P. , Navajas E. V., Altomare F., and Bernardini M. Q.. 2011. Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium causing paraneoplastic retinopathy: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011:631929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huynh, N. , Shildkrot Y., Lobo A.‐M., and Sobrin L.. 2012. Intravitreal triamcinolone for cancer‐associated retinopathy refractory to systemic therapy. J. Ophthalmic. Inflamm. Infect. 2:169–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ogra, S. , Sharp D., and Danesh‐Meyer H.. 2014. Autoimmune retinopathy associated with carcinoid tumour of the small bowel. J. Clin. Neurosci. 21:358–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saito, M. , Saito W., Kanda A., Ohguro H., and Ishida S.. 2014. A case of paraneoplastic optic neuropathy and outer retinitis positive for autoantibodies against collapsin response mediator protein‐5, recoverin, and α‐enolase. BMC Ophthalmol. 14:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Turaka, K. , Kietz D., Krishnamurti L., et al. 2014. Carcinoma‐associated retinopathy in a young teenager with immature teratoma of the ovary. J. AAPOS 18:396–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakamura, T. , Fujisaka Y., Tamura Y., Tsuji H., Matsunaga N., Yoshida S., et al. 2015. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung with cancer‐associated retinopathy. Case Rep. Oncol. 8:153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Javaid, Z. , Rehan S. M., Al‐Bermani A., and Payne G.. 2015. Unilateral cancer‐associated retinopathy: a case report. Scott. Med. J. pii: 0036933015598124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]