Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been the subject of many studies in recent years, ranging from basic science that looks into MSCs properties to studies that aim for developing bioengineered tissues and organs. Adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) have been the focus of most studies due to the inherent potential of these cells to differentiate into various cell types. Although, the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of cellular differentiation. These cells are another attractive stem cell source because of their ability to be reprogramed, allowing the generation of multiple cell types from a single cell. This paper briefly covers various types of stem cell sources that have been used for tissue engineering applications, with a focus on bone regeneration. Then, an overview of some recent studies making use of MSC-seeded 3D scaffold systems for bone tissue engineering has been presented. The emphasis has been placed on the reported scaffold properties that tend to improve MSCs adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation outcomes.

1. Introduction

Every year, more than 1 million surgical procedures involving the partial excision of bone, bone grafting, and fracture repair are performed in the USA, at an estimated cost of more than $5 billion [1–3]. A substantial percentage is for the elderly, the number of which is expected to double in the next 25 years [4]. Worldwide, fractures due to osteoporosis affect approximately one woman in three and one man in five over the age of 50 years and are a major cause of suffering and disability in the elderly population [5]. The repair rate of a bone defect is dependent on the wound size. When the defect size is greater than the healing capacity of osteogenic tissues, the fibrous connective tissue becomes dominant in the bone defect [2, 6]. Well-established clinical approaches are restricted to autograft and allograft transplantation. However, they are limited in availability and associated with postoperative complications [7, 8].

As an alternative, tissue engineering applies the knowledge of bioengineering, biology, cell transplantation, and materials science to construct biological substitutes that can restore and maintain normal function in injured and diseased bone [9, 10]. The tissue engineering approach often involves the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that are seeded into 3D scaffolds and induced to generate new bone by osteoinductive cues [11]. A fundamental requirement for tissue-engineered bone grafts is the ability to integrate with the host tissues, while providing the capacity for load-bearing and remodeling [12]. The size of scaffold-tissue constructs that can be cultured is limited due to high metabolic activity of bone cells [11]. This poses an additional challenge in terms of providing an efficient transport of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic wastes. Therefore, 3D scaffolds are designed to accommodate these mass transport requirements while offering a load-bearing matrix during the bone healing process [13]. Scaffold composition and surface properties also play a major role in MSCs proliferation and differentiation. Since bone is largely composed of hydroxyapatite (HA) [14], incorporating HA into scaffold formulation can enhance osteoconductivity [15, 16]. Nanostructured HA (nHA) has a higher surface area, and consequently higher reactivity [17], and can enhance MSCs adhesion, proliferation, alkaline phosphatase activity, calcium deposition, and osteogenic gene expression [18–20].

This paper briefly covers various types of stem cell sources that have been described in the scientific literature for use in tissue engineering applications. Then, an overview of some recent studies making use of MSC-seeded 3D scaffold systems for bone tissue engineering has been presented, while placing the emphasis on the recommendations made in these studies to further improve cell adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation outcomes. The majority of these studies have focused on bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) due to their high osteogenic potential [21–27]. The prospect of MSCs for bone tissue engineering has been summarized in the concluding section of this paper.

2. Stem Cell Sources for Bone Tissue Engineering

Bone tissue engineering requires a reliable stem cell source, in addition to appropriate 3D scaffolds and growth factors. Control over the differentiation of MSCs makes them attractive cell sources for bone tissue engineering. Adult stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (CB-MSCs) are among the candidates for bone tissue engineering applications [28–30]. In addition, adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction (SVF) has been reported to be an effective and abundant source for vascularization strategies, where regenerating vascularized bone tissues is desired [22]. Table 1 lists some of the advantages and disadvantages associated with these stem cell sources [22, 28, 29]. The following section further elaborates on the potential of these cell sources for bone repair and regeneration.

Table 1.

| Cell Source | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) | (i) High osteogenic potential (ii) Studied extensively |

Low abundance; requires extensive in vitro expansion |

|

| ||

| Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) | (i) Similar osteogenic characteristics as BM-MCSs (ii) Highly abundant; easy to harvest surgically |

More studies are needed to test their use in bone repair |

|

| ||

| Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) | (i) Pluripotency (ii) Capable of differentiating into all cell types in bone |

(i) Ethical and regulatory constraints (ii) Produce teratomas when transplanted in vivo |

|

| ||

| Umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (CB-MSCs) | (i) High availability (ii) Broad differentiation and proliferation potential (iii) Higher in vivo safety than embryonic stem cells |

(i) More difficult to be isolated than MSCs from the marrow (ii) More studies are needed to test their use in bone repair |

|

| ||

| Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) | (i) Pluripotency (ii) Capable of differentiating into all cell types in bone |

(i) Reprogramming efficiency is low (ii) Require extensive expansion (iii) Safety concerns; limited clinical application |

|

| ||

| Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction (SVF) | (i) Abundant; easily harvested via liposuction (ii) Able to form vascularized bone |

(i) Cell population varies among donors (ii) 2-3-hour multistep isolation process |

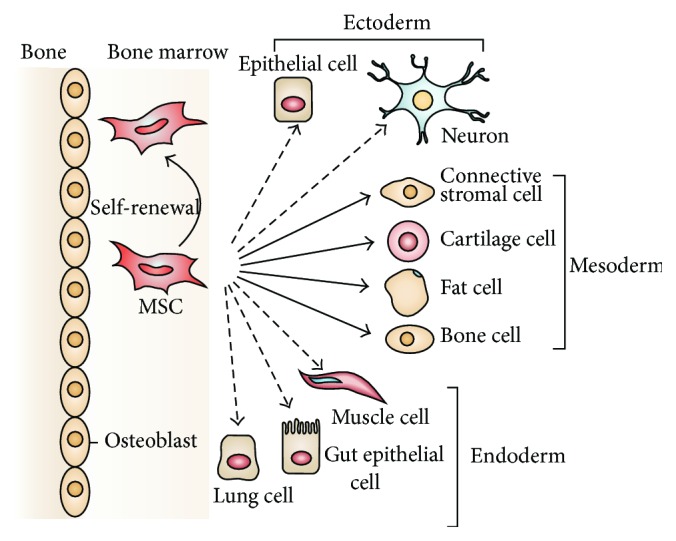

A high volume of research in bone tissue engineering has been devoted to adult stem cells, which can be isolated from tissues such as a bone marrow or adipose tissue. In particular, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) are attractive candidates due to their high osteogenic capacity [22]. As Figure 1 shows, MSCs in the bone marrow cavity can differentiate into cartilage, fat, and bone cells (mesoderm) and into several other cell types. Although stromal cells with similar characteristics can be isolated from almost any connective tissue [31], MSCs have mainly been characterized after isolation from the bone marrow [32]. However, relatively low abundance of BM-MSCs necessitates extensive in vitro expansion, which diminishes the posttranslational survival and immunomodulatory properties of BM-MSCs while posing regulatory and logistic challenges [22]. In addition, the donor and patient age is a critical factor that must be accounted for in laboratory and clinical evaluations [33].

Figure 1.

The ability of MSCs in the bone marrow cavity to self-renew (curved arrow) and to differentiate (straight, solid arrows) towards the mesodermal lineage (including bone cell). The reported ability to transdifferentiate into cells of other lineages (ectoderm and endoderm) is shown by dashed arrows, as transdifferentiation is controversial in vivo. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd., Nature Reviews Immunology, Uccelli et al. [32], copyright © 2008.

Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) are capable of differentiating into various cell types and possess similar osteogenic characteristics as BM-MSCs [34]. Human adipose tissue is abundant and can be easily obtained under local anesthesia with minimal patient discomfort, since a liposuction procedure is less invasive than bone marrow aspiration [28]. In addition, 1 g of adipose tissue can yield around 5 × 103 stem cells, making it 500-fold greater than the number of MSCs in 1 g of bone marrow [28, 35]. Clinical applications of ASCs are in practice today and show a great promise for future research. In a study, a 7-year-old female with posttraumatic calvarial defects was treated with autologous ASCs, fibrin glue, and a biodegradable scaffold. Postoperative new bone formation as well as relatively complete calvarial continuity was reported based on computed tomography analysis [28, 36].

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have a strong multilineage differentiation capability and can self-renew over long periods of time, which make them promising for use in regenerative medicine [37, 38]. Due to ethical and regulatory constraints associated with ESCs, cord blood has been reported to be the most attractive source of fetal MSCs [29]. This is also because of the existence of private and public cord blood banks that makes it a convenient source for potential therapeutic applications [29]. Unlike ESCs, there has been no report of teratomas production by cord blood MSCs (CB-MSCs); thus, these cells are safer than ESCs for clinical applications [29]. In general, the umbilical cord contains 60–80 cc of cord blood (CB) that contains ESCs and MSCs, as well as hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells [39]. However, more studies are needed to establish the potential of CB-MSCs for tissue engineering applications.

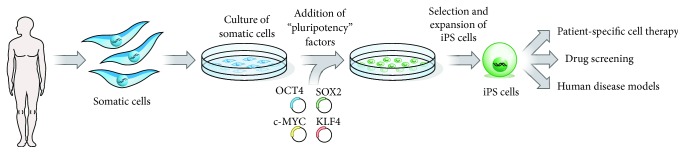

It has been reported that the overexpression of a single transcription factor in somatic cells can activate cohorts of genes that are typical of other somatic cell types and can remarkably change the cell fate [40–42]. The fact that, in many differentiated somatic cell types, pluripotency can be regained through overexpression of just four transcription factor encoding genes was a breakthrough that led to the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [42]. Figure 2 shows the steps for generating iPSCs from a typical somatic cell type (e.g., fibroblasts). Human iPSCs have been used for tissue repair and regeneration, enabling researchers to avoid the ethical and immunological issues associated with the use of embryonic stem cells (ESCs). In addition, iPSCs can be derived from a patient's own cells; therefore, they can be used to model human diseases and for drug screening in vitro [42]. In light of this, iPSCs are other attractive stem cell sources for tissue engineering because of their ability to be reprogramed, allowing the generation of multiple cell types from a single cell. Implantation of iPSCs in critical-sized calvarial defect of immune deficient mice has been shown to promote new bone formation and partial repair of the calvarial defect [43]. Based on recent clinical trials in Japan involving patients who had debilitating eye diseases [44], iPSCs are being considered as promising cell sources in clinical settings. However, the applications of both ESCs and iPSCs are at a preliminary stage, due to the limitations posed by ethical and political concerns, as well as the issues related to their genomic instability, immune rejection, and tumorigenesis [43].

Figure 2.

To generate iPSCs, fibroblasts (or another type of adult somatic cell) are transduced with retroviruses encoding four pluripotency factors (SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, and OCT4). Fully reprogrammed iPSCs have similar properties to ESCs. They are competent to form teratomas on injection into mice and are capable of generating progeny. Patient's cells can be used to derive iPSCs, which can then be induced to undergo differentiation into various types of somatic cells, all with the same genetic information as the patient. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd., Nature, Yamanaka & Blau [42], copyright © 2010.

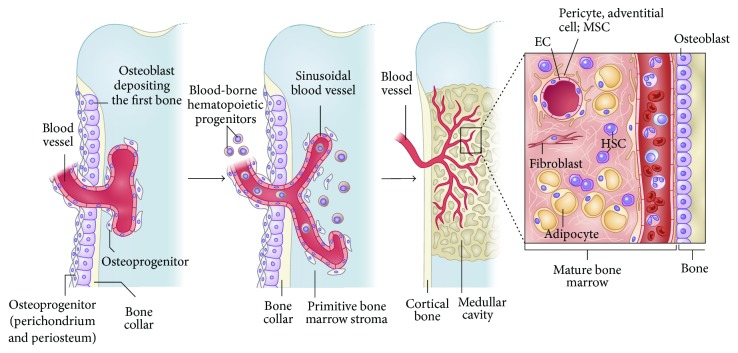

One of the greatest challenges in engineering of bone tissue of clinically relevant size is the mass transport limitations of nutrients and metabolic waste products [11]. Vascularization is thought to play a significant role in the healing process of tissue-engineered bone graft. The distribution of cells in a native bone tissue is usually limited to a distance of 200 μm from the nearest capillary, since for oxygen and nutrients this is an effective diffusion distance [45]. The MSCs in bone marrow reside at the outer surface of sinusoids blood vessels in a subendothelial (mural) position [46]. Figure 3 shows how MSCs make it to bone marrow, as a part of a three-dimensional perivascular stromal compartment that invade the bone anlage along with the growing blood vessels. In a recent paper, Bianco et al. have elaborated on this phenomenon while reviewing the nature, identity, function, and translational aspects of MSCs [46].

Figure 3.

How MSCs make it to bone marrow. During development, the primitive bone marrow stroma includes skeletal progenitors that originate outside of the marrow cavity (primitive periosteum and perichondrium) and invade the forming cavity along blood vessels. Similar dynamic interactions with ingrowing blood vessels are reproduced in transplants of human MSCs and are probably the basis for the perisinusoidal position of MSCs in the intact postnatal bone marrow. Recruitment of mesenchymal cells to a mural cell fate (and a subendothelial position), a general phenomenon in development and organ growth, is mediated by endothelial cell (EC) derived PDGF-BB, which signals through PDGFR-β expressed on mesenchymal cells (and MSCs). Presumptive mural cells (as well as human and mouse bone marrow MSCs) produce Ang-1, which is crucial for the integrity, survival, and remodeling of vascular lattices. Ang-1 also induces quiescence of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Both mural cells and endothelial cells are induced to mitotic quiescence by active TGF-β1, which is released through proteolytic cleavage of the latent form at sites of mural cell, endothelial cell contacts. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd., Nature Medicine, Bianco et al. [46], copyright © 2013.

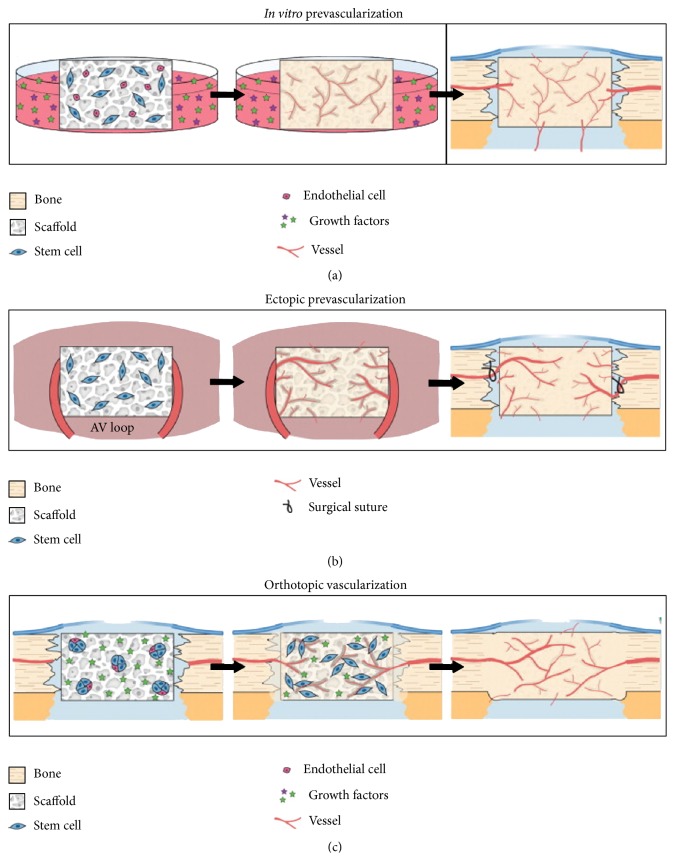

The existing clinical challenges have driven efforts toward the development of strategies for vascularized bone grafts. Hutton and Grayson have reviewed several different approaches for enhancing postimplantation cell viability in bone tissue engineering, including the concept of prevascularization. Vascular networks engineered in vitro can serve as conduits for rapid perfusion with blood after in vivo implantation [22]. As shown in Figure 4, these strategies may include in vitro prevascularization, ectopic prevascularization, and orthotopic vascularization. These strategies have been elaborated in a recent paper by Hutton and Grayson [22].

Figure 4.

Vascularization approaches for bone tissue engineering. (a) In vitro prevascularization techniques induce cell-seeded scaffolds to form vasculature via exogenous growth factors. Following implantation in the bone defect, these engineered capillaries will in theory rapidly anastomose to perfuse the entire graft. (b) In vivo ectopic prevascularization involves implantation of a cell-seeded scaffold into a highly vascularized bed, such as muscle or arteriovenous (AV) loop, to allow extensive vascular ingrowth. The graft is transplanted as a free flap to the bone defect and surgically anastomosed with the surrounding vessels to immediately perfuse the graft. (c) In vivo orthotopic vascularization involves direct implantation of scaffolds into the bone defect for in situ tissue development. Cells seeded into the scaffolds can be aggregated to improve cell survival and endogenous cell signaling. Scaffolds can be functionalized for the controlled release of growth factors (stars) that induce bone and vascular growth. Reprinted by permission from Elsevier Ltd., Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, Hutton & Grayson [22], copyright © 2014.

Heterogeneous cell sources containing multiple cell types (e.g., stem cells, endothelial cells, and pericytes) have been considered by a number of research teams to promote vascularization [22]. The idea is to combine pericytes with endothelial cells (ECs), featuring an intrinsic capacity to form stable vascular structures, while the stem cells undergo osteogenesis. As a typical candidate for heterogeneous cell sources, the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of adipose tissue contains both ASCs and ECs. Hutton and Grayson have compared various types of autologous stem/progenitor cell sources for engineering vascularized bone [22]. Robust in vitro culture protocols that enable synergistic development of both bone and vasculature have yet to be established. This is mainly because the biochemical cues that stimulate bone development have been shown to impede vascular growth and vice versa [22, 47, 48].

3. MSC-Seeded Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering

In scaffold-based tissue engineering, the idea is to combine a porous 3D scaffold with living cells and/or biologically active molecules to form a bioengineered construct, with the ability to promote the repair and/or regeneration of biological tissues [49]. The underlying hypothesis is that the internal architecture of the scaffold can serve as a substrate to guide the formation of a structured fibrous network, which is a prerequirement for later bone formation [50]. Scaffold design for bone tissue engineering involves many parameters that affect the mechanical properties of the scaffold while directly influencing the rate of tissue regeneration [51–53]. Overcoming the current challenges in scaffold-based tissue engineering could potentially be achieved through bioinspired approaches. Designing scaffolds with nanoscale topographical features and micro-/macroscale gradient structures, combined with biological domains to interact with target growth factors, is the key for successful tissue regeneration [54]. This section reviews some of the recent studies making use of MSC-seeded 3D scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, focusing on the recommendations made in these studies to further improve cell adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation outcomes.

To replicate the extraordinary strength and durability of natural bone, the current trend is to design biomaterials that nearly mimic the structural organization of bone from the nanoscale upward [55]. Many studies have incorporated nanostructures (such as nanoparticles or nanofibers) into scaffold formulations in order to enhance the mechanical properties of the scaffold. It has been reported that micro-/nanoscale interactions with extracellular matrix (ECM) components of the bone tissue can influence stem cell behaviors [56]. In a recent review article, Gong et al. [56] have elaborated on the classification and design of nanostructured materials, their cell interaction properties, and their application in bone tissue engineering.

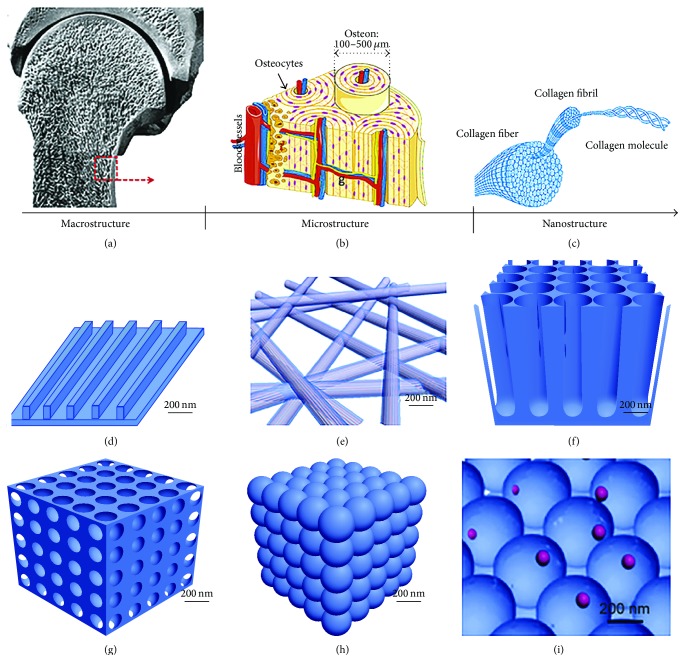

As shown in Figure 5(a), bone tissue consists of a compact shell (cortical bone) and a porous core (trabecular bone). Figure 5(b) shows the repeating osteon units within cortical bone as well as the trabeculae with bone marrow-filled free spaces within trabecular bone. These units are composed of collagen fibers (Figure 5(c)) and HA crystals, embedded within the gaps between collagen molecules to increase the rigidity of bone [56]. Given the hierarchical organization of the bone tissue, a key element in mimicking this hierarchy is to incorporate nano- and microscale features into 3D scaffolds. The commonly accepted definition of nanomaterials refers to materials with feature sizes ranging between 1 and 100 nm [56], including nanopattern [57], nanofibers [58], nanotubers [59], nanopores [60], nanospheres [61], and nanocomposites [62, 63] as depicted in Figures 5(d)–5(i) [56].

Figure 5.

The microstructure and nanostructure of bone and the nanostructured material used in bone regeneration. (a) At the macroscopic level, bone consists of a dense shell of cortical bone with porous cancellous bone at both ends. (b) Repeating osteon units within cortical bone. In the osteons, 20–30 concentric layers of collagen fibers, called lamellae, are arranged at 90° surrounding the central canal, containing blood vessels and nerves. (c) Collagen fibers (100–2000 nm) are composed of collagen fibrils. The tertiary structure of collagen fibrils includes a 67 nm periodicity and 40 nm gaps between collagen molecules. The hydroxyapatite (HA) crystals are embedded in these gaps between collagen molecules and increase the rigidity of the bone. Nanostructures with the features of nanopattern (d), nanofibers (e), nanotubers (f), nanopores (g), nanospheres (h), and nanocomposites (i) with structural components with a feature size in the nanoscale. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd., Bone Research, Gong et al. [56], copyright © 2015.

Some recent studies have combined additive manufacturing (AM) and electrospinning (ES) to produce bimodal scaffolds, so as to incorporate both nano- and microscale features into scaffold architecture [64, 65]. Additive manufacturing has been extensively used in recent years to produce prototypes of the designed scaffolds for experimental testing, enabling researchers to explore a wide range of scaffold topologies and their resulting effects on mechanical strength and tissue regeneration [53, 66–70]. On the other hand, electrospinning is a relatively simple technique to produce nonwoven mats of fibers with diameters ranging between several microns down to less than 100 nm [71, 72]. Electrospinning is considered to have unique advantages over some other scaffold fabrication techniques as it allows generating porous structures that could potentially mimic the natural ECM of biological tissues, while offering large surface areas and ease of functionalization for various biomedical applications [73, 74].

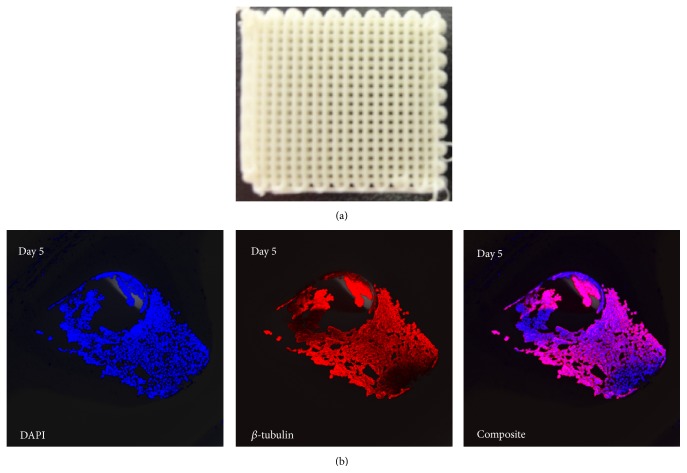

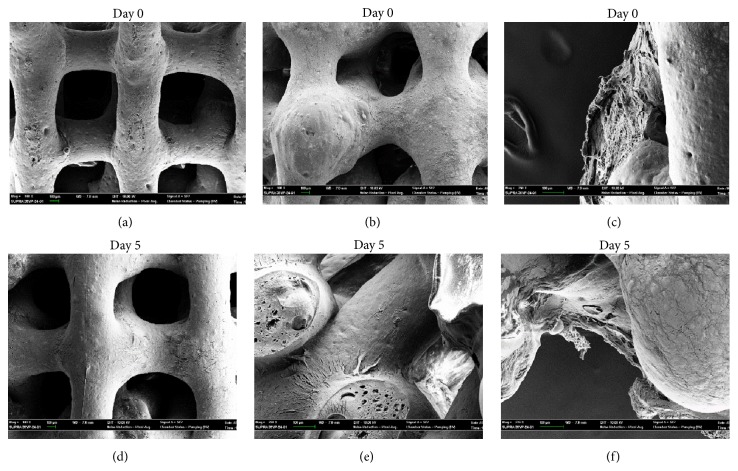

Nanostructured materials with surface properties favoring cell adhesion have a greater potential for stimulating new bone growth compared to conventional materials, making them superior for tissue engineering applications [55, 75, 76]. Figure 6(a) shows a 3D scaffold made of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA) produced by 3D-bioplotting technique (EnvisionTEC, Germany). DNA staining of the nuclei (DAPI) and anti-β-tubulin antibody staining of cells attached to these scaffolds 5 days after seeding with human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) are shown in Figure 6(b), demonstrating a uniform cell adhesion on the strand surface. Comparing the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the PLGA/nHA scaffolds before and after seeding with human MSCs reveals low cell adhesion on these scaffolds (Figure 7). This is partially due to the smooth surface of 3D-bioplotted strands, often encountered in most extrusion-based AM techniques. For scaffolds made of PLGA, a surface roughness at nanometer scale has shown to better support osteoblast functions as opposed to smooth surfaces [77]. Surface characteristics of 3D scaffolds, such as chemical composition, topography, and roughness, have been recognized as crucial factors affecting cell attachment and proliferation [78]. Micro- and nanostructured surfaces have significant effects on cell behavior [79]; therefore, combining AM techniques with conventional methods has also been explored in order to generate macro-/microporous scaffolds [80, 81].

Figure 6.

(a) Photomicrograph of a 3D-bioplotted PLGA/nHA scaffold; (b) DNA staining of the nuclei (DAPI) and anti-β-tubulin antibody staining of cell-seeded scaffolds on day 5 showing uniform cell adhesion onto the strands.

Figure 7.

SEM micrographs of hMSC-seeded PLGA/nHA scaffolds: (a) day zero, no cells; (b, c) day zero, with cells; (d) day 5, no cells; (e, f) day 5, with cells.

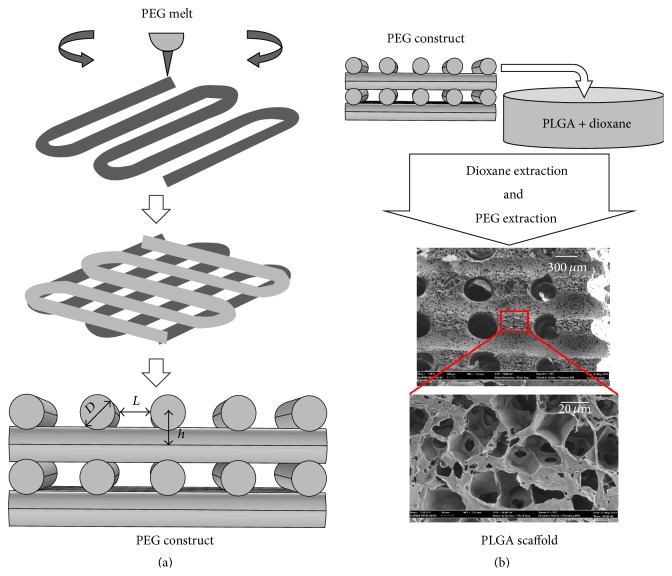

Figure 8 shows a hierarchical scaffold produced by a hybrid 3D-bioplotting/thermally induced phase separation (TIPS) technique. While the extraction of 3D-bioplotted polyethylene glycol (PEG) can lead to interconnected macrochannels (>300 μm in diameter), thermally induced phase separation produces micropores (<50 μm), and nanosized surface features favorable for cell adhesion [82]. The interconnected channels played a key role in MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cell seeding and thereby reduced the variability in cell attachment, viability, and proliferation observed in the TIPS-only scaffolds. Larger macrochannels (~490 μm, compared to ~360 μm) showed significantly higher cell retention, whereas the smaller macrochannels supported better cell proliferation [82]. This is consistent with curvature-driven tissue growth reported by others [83]. Surface modification of natural polymers with RGD groups containing specific molecular recognition sites has also been proposed to enhance various cellular activities on 3D scaffolds, including cell adhesion, cell-cell communication, and proliferation [84]. For example, the presence of gelatin in alginate scaffolds has been shown to enhance cell adhesion and proliferation of MSCs, while promoting the differentiation of MSCs into osteogenic cell lineage [85].

Figure 8.

Hybrid 3D-bioplotting/TIPS scaffold fabrication technique, (a) 3D-bioplotting of the PEG constructs and the adjustable bioplotting parameters, modified from [108]; (b) schematics of the scaffold fabrication process [82]. Figure 8(a) was reprinted by permission from John Wiley and Sons: Polymer Engineering & Science, Yousefi et al. [108], copyright © 2007. Figure 8(b) was reprinted with kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media: Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, 2015, 26:116, Akbarzadeh et al. [82], copyright © 2015.

In an effort to enhance the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs within 3D scaffolds, bioceramics such as hydroxyapatite (HA) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) have been extensively used by researchers [86–89]. Both HA and TCP have a chemistry similar to the mineral phase of natural bone. As a result, these bioceramics can promote the formation of an apatite layer on scaffold surface, leading to their integration to the host bone upon in vivo implantation [10, 90, 91]. Biodegradability of calcium phosphates can be controlled through regulation of the Ca/P ratio, although compounds with Ca/P ratio of less than 1 are not suitable for biological implantation due to the higher speed of hydrolysis with decreasing Ca/P ratio [92].

The nanoscale feature of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA) induces advantageous cellular responses when compared with micron-sized particles (mHA) [93]. This is mainly because the surface topography of a scaffold is one of the most crucial physical cues for cells. Both nanoscale and microscale topography can modulate cell behavior, including cell adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation [94]. Recent studies have shown that nanostructured surfaces lead to greater amounts of specific protein interactions and stimulate new bone formation more efficiently. This has led to the design of various nanostructured 3D scaffolds for tissue engineering applications [55].

Webster et al. have reported that 67 nm HA particles can significantly enhance osteoblast adhesion, when compared to conventional 179 nm HA particles after just 4 h of culture, while strikingly inhibit competitive fibroblast adhesion [16]. Nanophase ceramics have the highest adsorption of vitronectin, which is a protein promoting osteoblast adhesion. In addition, enhanced osteoclast-like cell functions and the formation of resorption pits have been reported on nHA, when compared to conventional HA [55]. Therefore, nHA is anticipated to have better bioactivity and improved biocompatibility compared to coarser crystals [95]. In another study, Cai et al. investigated the effect of nHA particles, namely, 20 ± 5, 40 ± 10 and 80 ± 12 nm in diameter, on the proliferation of BM-MSCs [96]. The in vitro results showed improved cytophilicity of the nanoparticles as compared with conventional HA (typically rod-like, 30–80 nm wide and 200–500 nm long). Greater proliferation of MSCs and cell viability were measured on the 20 nm sized particles [96]. Similarly, an in vivo study in a sheep model has shown that nHA coated metallic (Ti6Al4V) screws can provide superior bone ingrowth and osteointegration compared with mHA-coated screws [97].

Similar to calcium phosphate ceramics, bioactive glasses have many applications in bone tissue engineering due to their ability to bond to bone and promote bone growth [98]. When implanted in vivo, bioactive glasses induce an interfacial bioactive response. Under in vitro conditions, it has been reported that the ionic products from the dissolution of bioactive glasses enhance osteoblast attachment, proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization [99], while inducing the differentiation of BM-MSCs into mature extracellular producing osteoblasts [100]. It should be mentioned that bioactive glasses tend to have lower mechanical properties than cortical and cancellous bone, especially in porous form. This fact restricts the application of these materials in a wide range of biomedical applications [101].

The presence of certain ions in a doped bioactive glass can influence its biological properties [102]. For example, substituting strontium (Sr) for calcium in a bioactive glass can increase osteoblast proliferation and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, while inhibiting osteoclast-mediated resorption of CaP films [103]. Since Sr has chemical and physical properties similar to calcium (Ca), it is a natural bone-seeking element and around 98% of the Sr in human body is located in bone tissues [99]. It has been documented that Sr can promote osteoblast differentiation and survival [104] and is regarded as a bone-forming agent due to its stimulation of osteoprogenitor cells replication and collagen synthesis. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of Sr on bone forming cells is still under investigation. A few studies have indicated the dual effects of Sr delivery by bioactive glasses: the promotion of bone formation and reduction of bone resorption [102].

4. Concluding Remarks

Scaffold-based bone tissue engineering using stem cells is still at its infancy. A profound scientific knowledge of each specific stem cell type is necessary to identify how to translate them to clinic, which may necessitate entirely new practices [46]. For example, tissue engineering practices that require extensive in vitro culture and manipulation may impose a limitation on clinical translation. Therefore, the idea of using heterogeneous cell sources (e.g., adipose and bone marrow tissues) that do not require in vitro culture might result in greater efficacy [22]. This is particularly important as stem cells appear to possess mechanical memory and store information from past physical environments, which can influence the cell fate [105]. Overcoming the mass transport limitations for a bioengineered bone graft will pave the way to the treatment of larger bone defects. Current tissue engineering treatments are mostly intended for relatively small defects and are immature compared to native tissue [106]. Overall, there are many hurdles on the path for the treatment of chronic degenerative diseases and in regenerative medicine using MSCs [107]. Some of the other existing challenges include guaranteeing the long-term quality of repair and avoiding potential side effects of treatment such as carcinogenesis [107].

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Ohio Board of Regents/the Ohio Third Frontier Program grant entitled: “Ohio Research Scholars in Layered Sensing,” the Ohio Board of Regents grant entitled “Biological/Synthetic Scaffolds for the Repair of Bone Defects” (Figures 6–8), IDCAST, Miami University's Office for the Advancement of Research and Scholarship (OARS), the College of Engineering and Computing, and the Department of Biology. The authors also acknowledge the technical assistance of Joshua Minton, Dr. Richard Edelmann, Matt Duley, Doug Hart, Carlie Focke, Cara Janney, and the administrative assistance of Laurie Edwards.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. Health and Nutrition. Washington, DC, USA: US Census Bureau Statistical Abstracts of the United States; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y., Wu G., de Groot K. Biomimetic coatings for bone tissue engineering of critical-sized defects. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2010;7(5):S631–S647. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0115.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kretlow J. D., Mikos A. G. Review: mineralization of synthetic polymer scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13(5):927–938. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagoner Johnson A. J., Herschler B. A. A review of the mechanical behavior of CaP and CaP/polymer composites for applications in bone replacement and repair. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7(1):16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnell O., Kanis J. A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis International. 2006;17(12):1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz J. P., Hollinger J. O. The critical size defect as an experimental model for craniomandibulofacial nonunions. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1986;205:299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichert J. C., Wullschleger M. E., Cipitria A., et al. Custom-made composite scaffolds for segmental defect repair in long bones. International Orthopaedics. 2011;35(8):1229–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1146-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.den Boer F. C., Wippermann B. W., Blockhuis T. J., Patka P., Bakker F. C., Haarman H. J. T. M. Healing of segmental bone defects with granular porous hydroxyapatite augmented with recombinant human osteogenic protein-1 or autologous bone marrow. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2003;21(3):521–528. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00205-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vacanti J. P., Langer R. Tissue engineering: the design and fabrication of living replacement devices for surgical reconstruction and transplantation. The Lancet. 1999;354(supplement 1):SI32–SI34. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)90247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutmacher D. W. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials. 2000;21(24):2529–2543. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grayson W., Bhumiratana S., Cannizzaro C., Vunjak-Novakovic G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Assays and Applications. Vol. 698. Humana Press; 2011. Bioreactor cultivation of functional bone grafts; pp. 231–241. (Methods in Molecular Biology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhumiratana S., Vunjak-Novakovic G. Concise review: personalized human bone grafts for reconstructing head and face. Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 2012;1(1):64–69. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taboas J. M., Maddox R. D., Krebsbach P. H., Hollister S. J. Indirect solid free form fabrication of local and global porous, biomimetic and composite 3D polymer-ceramic scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2003;24(1):181–194. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isenberg B. C., Wong J. Y. Building structure into engineered tissues. Materials Today. 2006;9(12):54–60. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71743-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao S. S., Cui F.-Z. In vitro and in vivo degradation of mineralized collagen-based composite scaffold: nanohydroxyapatite/collagen/poly(L-lactide) Tissue Engineering. 2004;10(1-2):73–80. doi: 10.1089/107632704322791718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster T. J., Ergun C., Doremus R. H., Siegel R. W., Bizios R. Specific proteins mediate enhanced osteoblast adhesion on nanophase ceramics. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;51(3):475–483. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<475::AID-JBM23>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Z., Huang X., Cai Y., Tang R., Yang D. Size effect of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on proliferation and apoptosis of osteoblast-like cells. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5(1):338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K., Dean D., Lu A., Mikos A. G., Fisher J. P. Early osteogenic signal expression of rat bone marrow stromal cells is influenced by both hydroxyapatite nanoparticle content and initial cell seeding density in biodegradable nanocomposite scaffolds. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7(3):1249–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lock J., Nguyen T. Y., Liu H. Nanophase hydroxyapatite and poly(lactide-co-glycolide) composites promote human mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2012;23(10):2543–2552. doi: 10.1007/s10856-012-4709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sethuraman S., Nair L. S., El-Amin S., et al. Development and characterization of biodegradable nanocomposite injectables for orthopaedic applications based on polyphosphazenes. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2011;22(4–6):733–752. doi: 10.1163/092050610x491670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caplan A. I., Dennis J. E. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;98(5):1076–1084. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutton D. L., Grayson W. L. Stem cell-based approaches to engineering vascularized bone. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering. 2014;3:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geng W., Ma D., Yan X., et al. Engineering tubular bone using mesenchymal stem cell sheets and coral particles. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2013;433(4):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neman J., Hambrecht A., Cadry C., Jandial R. Stem cell-mediated osteogenesis: therapeutic potential for bone tissue engineering. Biologics: Targets and Therapy. 2012;6:47–57. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S22407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vernon L., Huang C. Y. C., Kaplan L. Stem cell based bone tissue engineering. In: Tal H., editor. Bone Regeneration. New York, NY, USA: InTech; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husain S. R., Ohya Y., Toguchida J., Puri R. K. Current status of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Tissue Engineering—Part B: Reviews. 2014;20(3, article 189) doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2014.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison R. H., St-Pierre J.-P., Stevens M. M. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: a year in review. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2014;20(1):1–16. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells for tissue repair and regeneration: ten years of research and a literature review. Journal of Nippon Medical School. 2009;76(2):56–66. doi: 10.1272/jnms.76.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coutu D. L., François M., Galipeau J. Mesenchymal stem cells and tissue repair. In: Allan D., Strunk D., editors. Regenerative Therapy Using Blood-Derived Stem Cells. Humana Press; 2012. pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grässel S., Lorenz J. Tissue-engineering strategies to repair chondral and osteochondral tissue in osteoarthritis: use of mesenchymal stem cells. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2014;16(10, article 452) doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva Meirelles L., Chagastelles P. C., Nardi N. B. Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. Journal of Cell Science. 2006;119(11):2204–2213. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uccelli A., Moretta L., Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2008;8(9):726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y., Charif N., Mainard D., Stoltz J., de Isla N. The importance of mesenchymal stem cell donor’s age for cartilage engineering. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2014;22(supplement):p. S61. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.02.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanetti A. S., Sabliov C., Gimble J. M., Hayes D. J. Human adipose-derived stem cells and three-dimensional scaffold constructs: a review of the biomaterials and models currently used for bone regeneration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research—Part B Applied Biomaterials. 2013;101(1):187–199. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fraser J. K., Wulur I., Alfonso Z., Hedrick M. H. Fat tissue: an underappreciated source of stem cells for biotechnology. Trends in Biotechnology. 2006;24(4):150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizuno H., Itoi Y., Kawahara S., Ogawa R., Akaishi S., Hyakusoku H. In vivo adipose tissue regeneration by adipose-derived stromal cells isolated from GFP transgenic mice. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;187(3):177–185. doi: 10.1159/000110805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang M., Chen W., Weir M. D., Thein-Han W., Xu H. H. K. Human embryonic stem cell encapsulation in alginate microbeads in macroporous calcium phosphate cement for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8(9):3436–3445. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domev H., Amit M., Laevsky I., Dar A., Itskovitz-Eldor J. Efficient engineering of vascularized ectopic bone from human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Engineering Part: A. 2012;18(21-22):2290–2302. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francese R., Fiorina P. Immunological and regenerative properties of cord blood stem cells. Clinical Immunology. 2010;136(3):309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneuwly S., Klemenz R., Gehring W. J. Redesigning the body plan of Drosophila by ectopic expression of the homoeotic gene Antennapedia . Nature. 1987;325(6107):816–818. doi: 10.1038/325816a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis R. L., Weintraub H., Lassar A. B. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987;51(6):987–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamanaka S., Blau H. M. Nuclear reprogramming to a pluripotent state by three approaches. Nature. 2010;465(7299):704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si J. Perinatal stem cells: a promising cell resource for tissue engineering of craniofacial bone. World Journal of Stem Cells. 2015;7(1, article 149) doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cyranoski D. Stem cells cruise to clinic. Nature. 2013;494(7438, article 413) doi: 10.1038/494413a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan H., Zeng X., Wang X., Zhu R., Pei G. Efficacy of prevascularization for segmental bone defect repair using β-tricalcium phosphate scaffold in rhesus monkey. Biomaterials. 2014;35(26):7407–7415. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bianco P., Cao X., Frenette P. S., et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nature Medicine. 2013;19(1):35–42. doi: 10.1038/nm.3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meury T., Verrier S., Alini M. Human endothelial cells inhibit BMSC differentiation into mature osteoblasts in vitro by interfering with osterix expression. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;98(4):992–1006. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Marco G. S., Hausberg M., Hillebrand U., et al. Increased inorganic phosphate induces human endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro. The American Journal of Physiology—Renal Physiology. 2008;294(6):F1381–F1387. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00003.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodruff M. A., Lange C., Reichert J., et al. Bone tissue engineering: from bench to bedside. Materials Today. 2012;15(10):430–435. doi: 10.1016/s1369-7021(12)70194-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cipitria A., Lange C., Schell H., et al. Porous scaffold architecture guides tissue formation. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(6):1275–1288. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanz-Herrera J. A., García-Aznar J. M., Doblaré M. On scaffold designing for bone regeneration: a computational multiscale approach. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5(1):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hollister S. J. Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nature Materials. 2005;4(7):518–524. doi: 10.1038/nmat1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giannitelli S. M., Accoto D., Trombetta M., Rainer A. Current trends in the design of scaffolds for computer-aided tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014;10(2):580–594. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang T., Carbone E. J., Lo K. W.-H., Laurencin C. T. Electrospinning of polymer nanofibers for tissue regeneration. Progress in Polymer Science. 2014;46:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L., Webster T. J. Nanotechnology and nanomaterials: promises for improved tissue regeneration. Nano Today. 2009;4(1):66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2008.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gong T., Xie J., Liao J., Zhang T., Lin S., Lin Y. Nanomaterials and bone regeneration. Bone Research. 2015;3:1–7. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2015.29.15029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim J., Kim H. N., Lim K.-T., et al. Designing nanotopographical density of extracellular matrix for controlled morphology and function of human mesenchymal stem cells. Scientific Reports. 2013;3, article 3552 doi: 10.1038/srep03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L., Zhou G., Wang Y., Yang G., Ding S., Zhou S. Controlled dual delivery of BMP-2 and dexamethasone by nanoparticle-embedded electrospun nanofibers for the efficient repair of critical-sized rat calvarial defect. Biomaterials. 2015;37:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xin Y., Jiang J., Huo K., Hu T., Chu P. K. Bioactive SrTiO3 nanotube arrays: osteoporotic bone implants. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2009;3(10):3228–3234. doi: 10.1021/nn9007675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lemaire T., Pham T. T., Capiez-Lernout E., de Leeuw N. H., Naili S. Water in hydroxyapatite nanopores: possible implications for interstitial bone fluid flow. Journal of Biomechanics. 2015;48(12):3066–3071. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang H., Leeuwenburgh S. C. G., Li Y., Jansen J. A. The use of micro- and nanospheres as functional components for bone tissue regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2012;18(1):24–39. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kotela I., Podporska J., Soltysiak E., Konsztowicz K. J., Blazewicz M. Polymer nanocomposites for bone tissue substitutes. Ceramics International. 2009;35(6):2475–2480. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2009.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogel M. R., Qiu H., Ameer G. A. The role of nanocomposites in bone regeneration. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2008;18(36):4233–4241. doi: 10.1039/b804692a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park S. H., Kim T. G., Kim H. C., Yang D.-Y., Park T. G. Development of dual scale scaffolds via direct polymer melt deposition and electrospinning for applications in tissue regeneration. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008;4(5):1198–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dalton P. D., Vaquette C., Farrugia B. L., Dargaville T. R., Brown T. D., Hutmacher D. W. Electrospinning and additive manufacturing: converging technologies. Biomaterials Science. 2013;1(2):171–185. doi: 10.1039/c2bm00039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turner B. N., Strong R., Gold S. A. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: I. Process design and modeling. Rapid Prototyping Journal. 2014;20(3):192–204. doi: 10.1108/rpj-01-2013-0012.17111231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parthasarathy J., Starly B., Raman S. A design for the additive manufacture of functionally graded porous structures with tailored mechanical properties for biomedical applications. Journal of Manufacturing Processes. 2011;13(2):160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jmapro.2011.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaezi M., Chianrabutra S., Mellor B., Yang S. Multiple material additive manufacturing. Part 1: a review. Virtual and Physical Prototyping. 2013;8(1):19–50. doi: 10.1080/17452759.2013.778175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Visser J., Peters B., Burger T. J., et al. Biofabrication of multi-material anatomically shaped tissue constructs. Biofabrication. 2013;5(3) doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/3/035007.035007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vlasea M., Pilliar R., Toyserkani E. Control of structural and mechanical properties in bioceramic bone substitutes via additive manufacturing layer stacking orientation. Additive Manufacturing. 2015;6:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2015.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y., Cui H., Zhuang X., Wei Y., Chen X. Electrospinning of aniline pentamer-graft-gelatin/PLLA nanofibers for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014;10(12):5074–5080. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Erben J., Pilarova K., Sanetrnik F., et al. The combination of meltblown and electrospinning for bone tissue engineering. Materials Letters. 2015;143:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.12.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang H., Fu Q.-W., Sun T.-W., et al. Amorphous calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite and poly(D,L-lactic acid) composite nanofibers: electrospinning preparation, mineralization and in vivo bone defect repair. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2015;136:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agarwal S., Wendorff J. H., Greiner A. Progress in the field of electrospinning for tissue engineering applications. Advanced Materials. 2009;21(32-33):3343–3351. doi: 10.1002/adma.200803092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yousefi A., Oudadesse H., Akbarzadeh R., Wers E., Lucas-Girot A. Physical and biological characteristics of nanohydroxyapatite and bioactive glasses used for bone tissue engineering. Nanotechnology Reviews. 2014;3(6) doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2014-0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yousefi A., Hoque M. E., Prasad R. G., Uth N. Current strategies in multiphasic scaffold design for osteochondral tissue engineering: a review. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2014;103(7):2460–2481. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith L. L., Niziolek P. J., Haberstroh K. M., Nauman E. A., Webster T. J. Decreased fibroblast and increased osteoblast adhesion on nanostructured NaOH-etched PLGA scaffolds. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2007;2(3):383–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu Y.-C., Shaw S.-Y., Lin H.-R., Lee T.-M., Yang C.-Y. Bone tissue engineering evaluation based on rat calvaria stromal cells cultured on modified PLGA scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2006;27(6):896–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Flemming R. G., Murphy C. J., Abrams G. A., Goodman S. L., Nealey P. F. Effects of synthetic micro- and nano-structured surfaces on cell behavior. Biomaterials. 1999;20(6):573–588. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liang Y., Zheng X., Zhai W., Sun T. 3D PLLA/nano-hydroxyapatite scaffolds with hierarchical porous structure fabricated by low-temperature deposition manufacturing. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology (Materials Science Edition) 2012;27(2):265–269. doi: 10.1007/s11595-012-0450-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu L., Xiong Z., Yan Y., Zhang R., Wang X., Jin L. Multinozzle low-temperature deposition system for construction of gradient tissue engineering scaffolds. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2009;88(1):254–263. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Akbarzadeh R., Minton J. A., Janney C. S., Smith T. A., James P. F., Yousefi A.-M. Hierarchical polymeric scaffolds support the growth of MC3T3-E1 cells. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2015;26(2, article 116) doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5453-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rumpler M., Woesz A., Dunlop J. W. C., van Dongen J. T., Fratzl P. The effect of geometry on three-dimensional tissue growth. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2008;5(27):1173–1180. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mano J. F., Reis R. L. Osteochondral defects: present situation and tissue engineering approaches. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2007;1(4):261–273. doi: 10.1002/term.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Petrenko Y. A., Ivanov R. V., Petrenko A. Y., Lozinsky V. I. Coupling of gelatin to inner surfaces of pore walls in spongy alginate-based scaffolds facilitates the adhesion, growth and differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2011;22(6):1529–1540. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chuenjitkuntaworn B., Osathanon T., Nowwarote N., Supaphol P., Pavasant P. The efficacy of polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite scaffold in combination with mesenchymal stem cells for bone tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part: A. 2016;104(1):264–271. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Minton J., Janney C., Akbarzadeh R., et al. Solvent-free polymer/bioceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: fabrication, analysis, and cell growth. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2014;25(16):1856–1874. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2014.953016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heo S. C., Shin W. C., Lee M. J., et al. Periostin accelerates bone healing mediated by human mesenchymal stem cell-embedded hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate scaffold. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116698.e0116698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Prosecká E., Rampichová M., Litvinec A., et al. Collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffold enriched with polycaprolactone nanofibers, thrombocyte-rich solution and mesenchymal stem cells promotes regeneration in large bone defect in vivo. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part: A. 2015;103(2):671–682. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith G. D., Knutsen G., Richardson J. B. A clinical review of cartilage repair techniques. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—British Volume. 2005;87(4):445–449. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b4.15971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mastrogiacomo M., Muraglia A., Komlev V., et al. Tissue engineering of bone: search for a better scaffold. Orthodontics and Craniofacial Research. 2005;8(4):277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2005.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hench L. L., Best S. M. Ceramics, glasses, and glass-ceramics: basic principles. In: Ratner B. D., Hoffman A. S., Schoen F. J., Lemons J. E., editors. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. 3rd. Elsevier; 2013. pp. 128–151. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li X., Wang L., Fan Y., Feng Q., Cui F.-Z., Watari F. Nanostructured scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101(8):2424–2435. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van der Sanden B., Dhobb M., Berger F., Wion D. Optimizing stem cell culture. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2010;111(4):801–807. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou H., Lee J. Nanoscale hydroxyapatite particles for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7(7):2769–2781. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cai Y., Liu Y., Yan W., et al. Role of hydroxyapatite nanoparticle size in bone cell proliferation. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2007;17(36):3780–3787. doi: 10.1039/b705129h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aksakal B., Kom M., Tosun H. B., Demirel M. Influence of micro- and nano-hydroxyapatite coatings on the osteointegration of metallic (Ti6Al4 V) and bioabsorbable interference screws: an in vivo study. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology. 2013;24(5):813–819. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hench L. L. Genetic design of bioactive glass. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2009;29(7):1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2008.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kaufmann E. A. B. E., Ducheyne P., Shapiro I. M. Effect of varying physical properties of porous, surface modified bioactive glass 45S5 on osteoblast proliferation and maturation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;52(4):783–796. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20001215)52:4<783::aid-jbm24>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Radin S., Reilly G., Bhargave G., Leboy P. S., Ducheyne P. Osteogenic effects of bioactive glass on bone marrow stromal cells. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2005;73(1):21–29. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mabrouk M., Mostafa A. A., Oudadesse H., Mahmoud A. A., El-Gohary M. I. Effect of ciprofloxacin incorporation in PVA and PVA bioactive glass composite scaffolds. Ceramics International. 2014;40(3):4833–4845. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jebahi S., Oudadesse H., El Feki H., et al. Antioxidative/oxidative effects of strontium-doped bioactive glass as bone graft. In vivo assays in ovariectomised rats. Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2012;10(4):195–209. doi: 10.2478/v10136-012-0009-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gentleman E., Fredholm Y. C., Jell G., et al. The effects of strontium-substituted bioactive glasses on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):3949–3956. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hamdy N. A. T. Strontium ranelate improves bone microarchitecture in osteoporosis. Rheumatology. 2009;48:9–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang C., Tibbitt M. W., Basta L., Anseth K. S. Mechanical memory and dosing influence stem cell fate. Nature Materials. 2014;13(6):645–652. doi: 10.1038/nmat3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Williams G. M., Chan E. F., Temple-Wong M. M., et al. Shape, loading, and motion in the bioengineering design, fabrication, and testing of personalized synovial joints. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010;43(1):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lane S. W., Williams D. A., Watt F. M. Modulating the stem cell niche for tissue regeneration. Nature Biotechnology. 2014;32(8):795–803. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yousefi A.-M., Gauvin C., Sun L., Diraddo R. W., Fernandas J. Design and fabrication of 3D-plotted polymeric scaffolds in functional tissue engineering. Polymer Engineering and Science. 2007;47(5):608–618. doi: 10.1002/pen.20732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]