Abstract

The activity of thermo-transient receptor potential (TRP) channels is highly dependent on temperature, and thus thermo-TRP reactions have a high temperature coefficient Q10. In thermodynamics, a high value of Q10 indicates the existence of a large activation energy (i.e., a large enthalpy) over a short period during the transition process between the closed and open states of the channels. The Gibbs free energy equation shows that a large entropy is required to compensate for this large enthalpy and permit activation of the channels, suggesting a large conformational change of the channels. These large values of enthalpy and entropy seem to be a match for the values of the unfolding process of globular proteins. We outline these thermodynamic issues in thermo-TRPs.

Keywords: enthalpy, entropy, Q10, temperature dependency, TRP channel

Thermo-TRP channels

Other articles in this Special Issue will provide general information on transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. In the present study, we focus on so-called “thermo-TRPs”, which are a subset of TRP channels. These channels are activated by distinct physiological temperatures, and are characterized by their unusually high temperature sensitivity (Q10 > 0; Q10 will be defined in the next section). TRPV1–V4 are activated by heat (>24°C), whereas TRPM8, TRPA1 and TRPC5 are activated by cold (<24°C). Although the values of Q10 for each channel have been reported to have a large variation [1–3], the table provided by Clapham and Miller is convenient as a standard reference (see Table 1 of the Clapham and Miller study) [4].

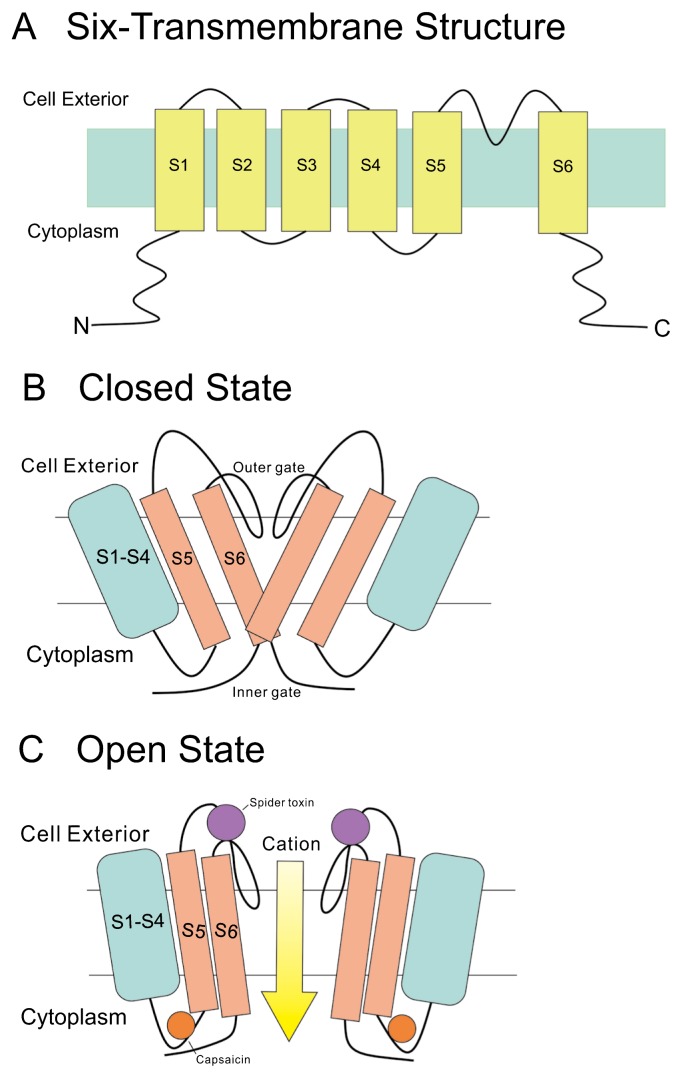

Structurally these thermo-TRPs are tetramers and each subunit contains six transmembrane domains (S1–S6), a hydrophobic pore loop linking transmembrane S5 and S6, and unusually large cytoplasmic N- and C-terminals (Fig. 1A). All thermo-TRPs have a variable number of ankyrin repeat domains in the N-terminus, except TRPM8, which has none and instead contains a TRPM homology region. Thermo-TRPs display distinct thermal thresholds from very noxious cold (TRPA1) to very harmful heat (TRPV2). Each thermo-TRP is also activated by specific natural or synthetic compounds that induce corresponding thermal and pain sensations in humans [5,6].

Figure 1.

Structure of TRP channel. A. All TRP channels appear to have six transmembrane segments like the voltage-gated potassium channels. Both the N and C terminals are intracellularly located. The C terminal is considered to play an important role in the activation mechanism by heat. B. The ion selectivity filter region is identified from the linear sequence, as they resemble the ion selectivity filter of potassium channels. Two gates (outer gate and inner gate) are apparent in the closed state, one near the extracellular surface (outer gate) and another deeper within the channel (inner gate). C. The outer gate opens in response to the binding of spider toxin, whereas the inner gate opens on binding of capsaicin [10]. The arrow indicates the passage of cations, mainly Ca2+, through the channel.

We still do not know exactly which part of a TRP channel senses temperature. However, previous studies strongly suggested that the C terminal plays an important role in activation mechanism by temperature change. (1) The deletion of some amino acids from the C terminal affected channel activation by heat [1]. (2) When the whole C terminal was switched between TRPV1 and the cold activated TRPM8, their temperature sensitivity properties were also swapped [3]. (3) The regions including the C terminal shifted the activation threshold temperature [7].

On the other hand, the binding sites with spider toxin and capsaicin, which result in activation of TRPV1, have been clarified based on structures [8,9] obtained using electron cryo-microscopy. From this information, one schematic presentation for the closed and open states of TRPV1 was suggested [10]. This scheme seems important for the activation by temperature change, too (Fig. 1B, C).

Temperature coefficient Q10

The reaction rate in biological systems is temperature-dependent without exception. To model this dependency, the temperature coefficient (Q10) is widely used; Q10 provides that the rate of a reaction increases for every 10-degree rise in the temperature. The definition of Q10 is given by the van’t Hoff equation as follows:

| (eq. 1) |

Here, k1 is the reaction rate measured at T1 degrees, and k2 is the reaction rate measured at T2 degrees. Note that the unit of T1 and T2 is Celsius or Kelvin and that T1 and T2 do not need to be exactly 10 degrees apart. If the reaction rate increases with increasing temperature, Q10 is greater than 1. For most mesophilic enzymes, Q10=2–3 [11]. This shows that the rate of the reaction doubles or triples with every 10 K rise in temperature. The more temperature-dependent a process is, the higher is its Q10 value. If Q10=1, the reaction can be explained by the diffusion of ions, and if Q10 values are greater than 2, the processes are thought to involve a large-scale protein conformational change, which will be discussed later.

Activation energy (enthalpy) corresponding to high Q10

The Arrhenius equation is another formula used to present the temperature dependence of reaction rates. This equation is also based on the van’t Hoff equation for the temperature dependence of equilibrium constants:

| (eq. 2) |

Here k is the reaction rate, A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin.

When the activation energies are obtained from two different temperatures, T1 and T2, with a difference of 10 degrees, we have:

We calculate Q10 as

| (eq. 3) |

Suppose two Q10 in which Q10α>Q10β, then

| (eq. 4) |

and we obtain the relation between the two activation energies, Eα>Eβ. Therefore, the high Q10 value of thermo-TRPs corresponds to the large activation energy Ea. For example, if Q10=20.0 within the temperature range of 303–313 K, we obtain Ea=226.4 (kJ mol−1), and if Q10=2.0 within the same temperature range, Ea=52.4 (kJ mol−1). That is, when Q10 is ten-fold, the activation energy Ea is about four-fold.

For ion channels, Q10 can be measured from the whole-cell currents during temperature ramps, when the cells are maintained at a certain holding potential. For example, Voets et al. (2004) calculated from their own experimental data that Ea of the “opening” rate of TRPM8 was 15.7 kJ mol−1 and its corresponding Q10 was 1.2, whereas Ea of the “closing” rate of TRPM8 was 173 kJ mol−1 and its corresponding Q10 was 9.4 [12]. This result confirmed that a high Q10 value indicates a large activation energy Ea but showed that the barriers might be different between the opening process and the closing process.

The activation energy described above is equivalent to the “enthalpy”, because all these values are derived from the same van’t Hoff equation. Here, let us consider the slope of the van’t Hoff plot for enthalpy. The change in the standard-state Gibbs free energy between 2 states (e.g., the open and closed states of channels) at a given temperature and pressure is expressed as

| (eq. 5) |

Here, k is an equilibrium constant, corresponding to the reaction rate. Because the intrinsic difference in standard-state Gibbs free energy is

| (eq. 6) |

the above two equations give

| (eq. 7) |

When we use Equation 3 again for Q10,

we can express this Q10 in a logarithmic form by use of Equation 7,

| (eq. 8) |

| (eq. 9) |

Namely, we have the identical values for activation energy and enthalpy corresponding to the same Q10 in Equation 3. In some previous papers, the activation energy is referred to as the activation “enthalpy” [13].

Further, Equation 3 shows that Q10 is a function of temperature, so that when Ea is supposed to be constant, Q10 is higher in the low temperature range, whereas Q10 is lower in the high temperature range.

Entropy corresponding to high Q10

To reduce ΔG0, or to hold ΔG0 to a small value, it is necessary that ΔS0 of Equation 6 be sufficiently large [14]. We calculate that ΔS0= 0.723 (kJ mol−1 K−1) in the case of ΔH0= 226.4 (kJ mol−1) and T = 313 (K), in order to obtain ΔG0= 0 (kJ mol−1) at Q10 = 20.0. Indeed, such a compensation of ΔH0 and ΔS0 was confirmed in experiments for several different thermo-TRPs, most of which were performed by the Voets group [12,15–20]. In brief, these large values of enthalpy and entropy appear to be comparable with the values for “unfolding” of globular proteins (see Table 1 of the Robertson and Murphy study) [21].

As seen above, some thermo-TRPs with high Q10 require very large enthalpies and entropies. We now express enthalpy and entropy by the use of heat capacity [14], because a conformational change in proteins is thought to be accompanied with a change in heat capacity.

| (eq. 10) |

| (eq. 11) |

Here, ΔCp is a molar heat capacity and independent of T, and Tref is a reference temperature chosen arbitrarily (e.g., standard ambient temperature, 298.15 K). Now we can substitute Equations 10 and 11 into Equation 7:

| (eq. 12) |

This Equation 12 demonstrates a U-shaped curve (but almost flat) when 0 < T<2Tref, and it takes the minimum value at T = Tref, because the first derivative at T = Tref. When ΔCp increases, the curvature of the U shape becomes acute.

Conformational changes of thermo-TRPs with high Q10

Clapham and Miller (2011) remarked that, in Equation 12, the value of ΔCp tends to be large and the curve tends to be U-shaped, and their analysis of this phenomenon deepened the understanding of thermo-TRPs underlying the temperature sensing [4]. If a TRP domain containing buried hydrophobic groups is thrust into a solvent upon channel opening, Cp is thought to increase. The conclusion from their theoretical analysis is as follows: “if 10–20 side chains in a TRP subunit—or indeed lipid moieties, which are, after all, part of the thermodynamic system—become exposed to water upon channel opening, the properties discussed here must emerge. They are necessary, direct consequences of the First and Second Laws of thermodynamics. Adding more states to account for what is undoubtedly a multistep process does not alter this argument. As long as the function of hot- and cold-sensing TRPs involves the exposure of ≈20 nonpolar residues upon gating, then thermodynamics requires that a channel activated by high temperatures will also be activated [by] low temperatures (and vice versa).” If this scenario is true, the activation process of some thermo-TRPs resembles the “unfolding” or “denaturation” process of globular proteins [22].

More recently, Chowdhury and colleagues employed a protein engineering approach and the ΔCp ideas to design a temperature-sensitive channel. They built thermosensitivity “bottom-up” into Shaker-like K+ channels belonging to the same superfamily as TRPs, whose normal voltage-driven activation process is nearly temperature-independent [23]. They showed that the specific heat capacity change during channel gating is a major determinant of thermosensitive gating.

On the other hand, Jara-Oseguera and Islas (2013) have proposed an allosteric model (8-state model) that determines the temperature-dependent activity of thermo-TRPs, and have claimed that the properties in response to both cooling and heating can be explained in a “ΔCp-independent” manner [24]. They showed that the activation of cold-activated channels can be achieved by a heat-activated temperature sensor that is characterized by positive ΔH0 and ΔS0 values. This fact is consistent with the notion that the activation by elevated temperature is accompanied by significant hysteresis, at least in the TRPV1, TRPV2 and TRPV3 channels [25–27]. These ideas are also supported by the similarity to protein folding/unfolding processes, as described in the following section.

They also agreed that the channel activity of thermo-TRPs shares some properties with folding/unfolding processes of proteins [25,27]. For example, the exposure of buried residues to the solvent and the breaking of some intermolecular interactions may occur in TRP channel activation in response to a change in temperature that can be observed as the molecular events accompanying a protein unfolding reaction. However, from the viewpoint that the channel activation is “ΔCp-independent” (but the protein thermal denaturation is usually associated with large changes in heat capacity), Jara-Oseguera and Islas claimed that a small conformational change involving no more than 50 residues, which was hypothesized by Clapham and Miller [4], does not have to be accompanied by a large change in heat capacity [24]. Jara-Oseguera and Islas described [24] that “the exposure of hydrophobic protein regions to water that results in an increase in heat capacity could very well be balanced by the exposure of polar protein regions to the solvent, which reduces heat capacity [28].”

De novo structure control mechanism of TRP channels

Much progress has been made in the structural analysis of channel pores in relation to thermo-TRPs [8,12,20,29]. Recently, the Yamashita group investigated a fungal TRP channel, TRPGz, and reported that the structure of a cytosolic C-terminal domain, which is required to activate hyperosmosis and temperature increase, is a four-α helix bundle assembled in an offset spiral, with weaker interprotomer interactions [30]. This bundle structure is not always formed, and even when formed can easily come apart. When this bundle is formed, TRGz opens the channel in response to a temperature increase. On the other hand, TRP channels are inactivated by the binding with phosphatidylinositol 4,5- bisphosphate (PIP2) [31,32], which has 5 to 6 negative charges from three PO4 groups. It is only after the above-described cytosolic C-terminal domain bundle comes completely apart that the interaction between the basic cluster of the cytosolic C-terminal domain and the PIPs (including PIP2) on the vacuolar membrane (organelle in animal cells) inhibits the channel activity, showing that the binding and disjunction of this four-α helix bundle plays an important role in the opening and closing processes of TRP channels. This phenomenon may be due to Coulomb interaction. This binding and disjunction of a bundle may also explain the findings of Voets et al.that the values of Q10 and Ea differed between the opening rate and the closing rate [12].

Perspective: Involvement of a change in vicinal water of the cytosol in hyperthermia cancer treatment

Recently, Mentré proposed a novel theory about the role of water in the cell, based on numerous results obtained in the field of physical chemistry [33]. Mentré maintains that misinterpretations of electron microscopy images have led researchers to completely overlook the existence of interfacial bound water. The interfacial water is the strongly constrained water surrounding proteins (i.e., bound water). The highly heterogeneous structure of this water layer reflects the heterogeneity of the protein surface. The interfacial water presents a large range of densities. Therefore, the changes in protein configuration must result in changes in the volume of the bound water, and thereby in the mechanical effects of the bound water. Mentré further avers that the whole cell water (70–80% of total mass) is distributed into only two to three hydration layers around proteins or macromolecules. Consequently, the average thickness of the space between the proteins in cells is estimated as only 1.2 nm [34]. In addition, the mean distance between two free Ca2+ ions is calculated as 55 nm at the concentration of 10 μM in cells [34]. Because the mean size of globular proteins is estimated as 3–5 nm, these Ca2+ ions are separated by tens of, or even hundreds of, proteins. If so, many previous analyses of electrophysiological data would have to be changed, because ions cannot move by diffusion process in living cells.

Mentré’s theory could offer great insight into the further development of cancer treatments. The classical concept of the Hofmeister series showed that Na+ is naturally excluded from the interfacial water (i.e., bound water), but K+ is little or not excluded from the interfacial water [35–37]. However, the vicinal water surrounding proteins in cancer cells is changed to free water (i.e., bulk water) and releases K+, resulting in an increase in intracellular K+ concentration. This result was confirmed by NMR experiments [38]. In other words, the water in cancer cells is thought to be easily moved via diffusion. Therefore, many of the results obtained so far by using cancer cell lines must be carefully revisited in studies using normal cells. Further, such differences between cancer cells and normal cells may explain why “hyperthermia treatment induced at 43°C” can selectively kill cancer cells even if normal and cancer cells are equipped with the same kinds of thermo-TRPs. Thermo-TRPs may play an important role in cancer treatment. The details for this hyperthermia mechanism will be discussed in the near future.

In conclusion, a high Q10 of thermo-TRPs requires both large enthalpy and large entropy values. This indicates that the activation process of the thermo-TRPs resembles an unfolding process of globular proteins. The structure of the water surrounding thermo-TRPs is expected to change in response to the change in the structure of thermo-TRPs. The contribution of the entropy term, as well as the enthalpy term, to ion permeation barriers has also been observed in another channel (K+ channel) by molecular dynamics simulations [39].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All the authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Author Contributions

E. I. and T. Y. directed the entire project. E. I. and Y. I. calculated the data. E. I., Y. I. and Y. T. co-wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Vlachová V, Teisinger J, Susánková K, Lyfenko A, Ettrich R, Vyklický L. Functional role of C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of rat vanilloid receptor 1. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1340–1350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01340.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brauchi S, Orio P, Latorre R. Clues to understanding cold sensation: thermodynamics and electrophysiological analysis of the cold receptor TRPM8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15494–15499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406773101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brauchi S, Orta G, Salazar M, Rosenmann E, Latorre R. A hot-sensing cold receptor: C-terminal domain determines thermosensation in transient receptor potential channels. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4835–4840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5080-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clapham DE, Miller C. A thermodynamic framework for understanding temperature sensing by transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19492–19497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117485108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latorre R, Zaelzer C, Brauchi S. Structure-functional intimacies of transient receptor potential channels. Q Rev Biophys. 2009;42:201–246. doi: 10.1017/S0033583509990072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrandiz-Huertas C, Mathivanan S, Wolf CJ, Devesa I, Ferrer-Montiel A. Trafficking of ThermoTRP Channels. Membranes (Basel) 2014;4:525–564. doi: 10.3390/membranes4030525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao J, Liu B, Qin F. Modular thermal sensors in temperature-gated transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11109–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105196108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao M, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. Structure of the TRPV1 ion channel determined by electron cryo-microscopy. Nature. 2013;504:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao E, Liao M, Cheng Y, Julius D. TRPV1 structures in distinct conformations reveal activation mechanisms. Nature. 2013;504:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson R. Structural biology: Ion channel seen by electron microscopy. Nature. 2013;504:93–94. doi: 10.1038/504093a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elias M, Wieczorek G, Rosenne S, Tawfik DS. The universality of enzymatic rate-temperature dependency. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voets T, Droogmans G, Wissenbach U, Janssens A, Flockerzi V, Nilius B. The principle of temperature-dependent gating in cold- and heat-sensitive TRP channels. Nature. 2004;430:748–754. doi: 10.1038/nature02732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuno M, Ando H, Morihata H, Sakai H, Mori H, Sawada M, Oiki S. Temperature dependence of proton permeation through a voltage-gated proton channel. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:191–205. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumry R, Rajender S. Enthalpy-entropy compensation phenomena in water solutions of proteins and small molecules: a ubiquitous properly of water. Biopolymers. 1970;9:1125–1227. doi: 10.1002/bip.1970.360091002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voets T, Owsianik G, Janssens A, Talavera K, Nilius B. TRPM8 voltage sensor mutants reveal a mechanism for integrating thermal and chemical stimuli. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:174–182. doi: 10.1038/nchembio862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talavera K, Yasumatsu K, Voets T, Droogmans G, Shigemura N, Ninomiya Y, Margolskee RF, Nilius B. Heat activation of TRPM5 underlies thermal sensitivity of sweet taste. Nature. 2005;438:1022–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature04248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karashima Y, Talavera K, Everaerts W, Janssens A, Kwan KY, Vennekens R, Nilius B, Voets T. TRPA1 acts as a cold sensor in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1273–1278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808487106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao J, Liu B, Qin F. Kinetic and energetic analysis of thermally activated TRPV1 channels. Biophys J. 2010;99:1743–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vriens J, Owsianik G, Hofmann T, Philipp SE, Stab J, Chen X, Benoit M, Xue F, Janssens A, Kerselaers S, Oberwinkler J, Vennekens R, Gudermann T, Nilius B, Voets T. TRPM3 is a nociceptor channel involved in the detection of noxious heat. Neuron. 2011;70:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang F, Cui Y, Wang K, Zheng J. Thermosensitive TRP channel pore turret is part of the temperature activation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7083–7088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000357107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson AD, Murphy KP. Protein structure and the energetics of protein stability. Chem Rev. 1997;97:1251–1268. doi: 10.1021/cr960383c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta P, Garrity P. Sensing temperature. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury S, Jarecki BW, Chanda B. A molecular framework for temperature-dependent gating of ion channels. Cell. 2014;158:1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jara-Oseguera A, Islas LD. The role of allosteric coupling on thermal activation of thermo-TRP channels. Biophys J. 2013;104:2160–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caterina MJ, Rosen TA, Tominaga M, Brake AJ, Julius D. A capsaicin-receptor homologue with a high threshold for noxious heat. Nature. 1999;398:436–441. doi: 10.1038/18906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu H, Ramsey IS, Kotecha SA, Moran MM, Chong JA, Lawson D, Ge P, Lilly J, Silos-Santiago I, Xie Y, DiStefano PS, Curtis R, Clapham DE. TRPV3 is a calcium- permeable temperature-sensitive cation channel. Nature. 2002;418:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu B, Yao J, Zhu MX, Qin F. Hysteresis of gating underlines sensitization of TRPV3 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138:509–520. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabhu NV, Sharp KA. Heat capacity in proteins. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2005;56:521–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ute A, Hellmich RG. Structural biology of TRP channels. Mammalian Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Cation Channels Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2014;223:963–990. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05161-1_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ihara M, Hamamoto S, Miyanoiri Y, Takeda M, Kainosho M, Yabe I, Uozumi N, Yamashita A. Molecular bases of multimodal regulation of a fungal transient receptor potential (TRP) channel. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15303–15317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T. Transient receptor potential channels meet phosphoinositides. EMBO J. 2008;27:2809–2816. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hille B, Dickson EJ, Kruse M, Vivas O, Suh BC. Phosphoinositides regulate ion channels. Biochim Biophys Acta Molec Cell Biol Lipid. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mentré P. Water in the orchestration of the cell machinery. Some misunderstandings: a short review. J Biol Phys. 2012;38:13–26. doi: 10.1007/s10867-011-9225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mentré P. An introduction to “Water in the cell”: tamed hydra? Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2001;47:709–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunz W, Henle J, Ninham BW. ‘Zur Lehre von der Wirkung der Salze’ (about the science of the effect of salts): Franz Hofmeister’s historical papers. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;9:19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Cremer PS. Interactions between macromolecules and ions: the Hofmeister series. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X, Yang T, Kataoka S, Cremer PS. Specific ion effects on interfacial water structure near macromolecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12272–12279. doi: 10.1021/ja073869r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beall PT, Hazlewood CF, Rao PN. Nuclear magnetic resonance pattern of intracellular water as a function of HeLa cell cycle. Science. 1976;192:904–907. doi: 10.1126/science.1273575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Portella G, Hub JS, Vesper MD, de Groot BL. Not only enthalpy: large entropy contribution to ion permeation barriers in single-file channels. Biophys J. 2008;95:2275–2282. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]