Abstract

TRP channels are expressed in various cells in skin. As an organ system to border the host and environment, many nonneuronal cells, including epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes, express several TRP channels functionally distinct from sensory processing. TRPV1 and TRPV3 in keratinocytes of the epidermis and hair apparatus inhibit proliferation, induce terminal differentiation, induce apoptosis, and promote inflammation. Activation of TRPV4, 6, and TRPA1 promotes regeneration of the severed skin barriers. TRPA1 also enhances responses in contact hypersensitivity. TRPCs in keratinocytes regulate epidermal differentiation. In human diseases with pertubered epidermal differentiation, the expression of TRPCs are altered. TRPMs, which contribute to melanin production in melanocytes, serve as significant prognosis markers in patients with metastatic melanoma. In summary, not only act in sensory processing, TRP channels also contribute to epidermal differentiation, proliferation, barrier integration, skin regeneration, and immune responses. In diseases with aberrant TRP channels, TRP channels might be good therapeutic targets.

Keywords: TRP channels, keratinocytes, skin

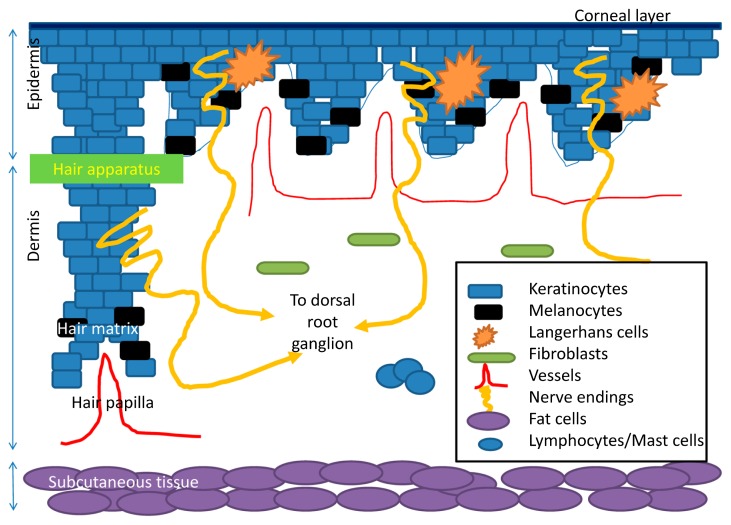

Skin is the largest organ in the human body. It is composed of three major components (Fig. 1). The superficial component is the epidermis, which includes several layers of keratinocytes. Basal keratinocytes in epidermis proliferate to generate suprabasal keratinocytes, which undergo further differentiation, eventually to the cells devoid of nuclei in the corneal layer. These corneal keratinocytes, also termed terminal differentiated cells, together with the dense intercellular structures, make up the delicate and solid skin barriers. The intact skin barrier prevents noxious substance and pathogens enter into human body and prevents water vaporization from inside. Melanocytes reside near basal keratinocytes. Melanocytes produce melanins and transfer the melanins to adjacent keratinocytes. Langerhans cells, the professional antigen presenting cells in the epidermis, capture foreign or endogenous antigens, migrate to regional lymph nodes to prime specific clones of T cells. The middle component of skin is the dermis. The dermis includes extracellular matrix, collagens, as well as endothelial cells, mast cells, and fibroblasts. The dermis provides the nutritional and vascular network and contributes mainly to the physical property of the skin. Abnormal wound healing may occur with excess deposition of extracellular matrix and/or collagens as well as fibroblast and vessels. The dermis also provides a transit for the peripheral nerve endings from the epidermis to the deep skin. The deep component of skin is the subcutaneous tissue, which provides adequate heat insulation and serve as energy storage.

Figure 1.

A brief schematic figure for skin structure. Skin is made of epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. In epidermis, keratinocytes are the major population of the cells. Keratinocytes undergo terminal differentiation to form anuclear corneal layer as major skin barriers. Melanocytes produce melanins and transfer them to the adjacent keratinocytes. Langerhans cells are professional antigen presenting cells in epidermis. They uptake antigens and present them to corresponding T cells. In dermis, there are vascular channels providing the oxygen and nutrient to the overlying epidermis and the hair papilla, adjacent to hair matrix, the lowest part of the hair apparatus. Hair apparatus is made of several layers of keratinocytes. Melanocytes in hair matrix provide melanins for hair apparatus. Subcutanous tissue is mainly made of fat tissues and supplying vessels. Free nerve endings from dorsal root ganglion radiate to dermis and penetrate into the epidermis.

As an integrative system, skin mediates the sensory function, provides an immunological barrier, maintains skin homeostasis, and produces melanin pigments. Based on the available evidences, the TRP channels might play a role in mediating or regulating these physiological functions. Furthermore, the perturbance in the function and/or in the expressions of TRP channels can contribute to skin inflammation, abnormal differentiation, pigmentary diseases, and perhaps carcinogenesis.

TRP channels in skin

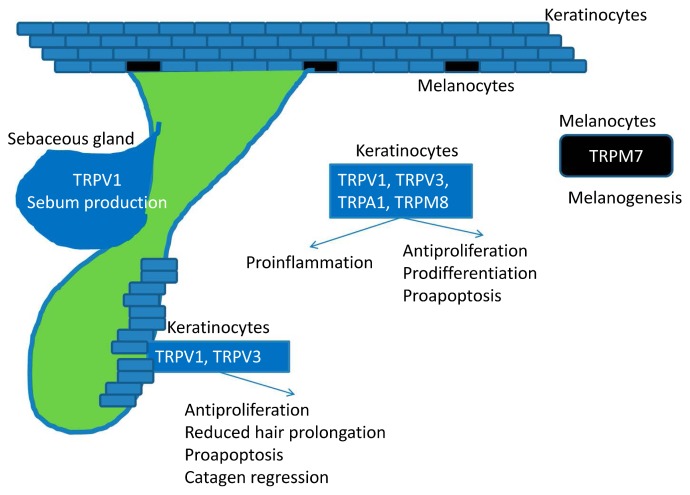

Besides the sensory function of TPR channels (such as itch) in nerve endings in skin, this review focuses on the role of TRP channels in the non-neuron cells, such as epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes. In fact, populations of non-neuronal cells within the skin express many different types of TRP channels, which contribute to various key cutaneous functions including skin-derived pruritus, proliferation, differentiation, cancer and inflammatory processes. The possible functions of TRP channels in skin are summarized in Table 1. In the following section, we focus on TRPV1, TRPV3, TRPA1, TRPCs, and TRPM (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Expression and function of TRP channels in nonneuronal cells of skin

| Keratinocytes | Outer root sheath cells in hair follicle | Implications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | Activation:

TRPV1 KO is impaired in skin inflammation [56] |

Activation:

|

Increased expressions in prurigo nodularis [3] and aged skin [57]. PAC-14028 TRPV1 antagonist improves atopic-like skin in mice [58] TPRV1 KO are tumor-prone [59] |

| TRPV3 | Antiproliferation and proapoptosis [19] Release of NO [60], cytokines, PGE2 [8] Promotion of cell migration and wound healing [50] TRPV3 KO have impaired skin barrier; wavy hair coat, curly whiskers [16] |

Antiproliferation and proapoptosis Impaired hair shaft elongation [19,61] |

TRPV1 “Gain-of-function” mutation results in pruritic AD like skin [18,21] Human Olmsted syndrome by Gly573Ser mutation manifestes as mutilating palmoplantar keratoderma [62] |

| TRPV4 | Enhancing barrier regeneration [10] TRPV4 KO have impaired skin barrier, poor differentiation [63] |

||

| TRPV6 | Calcium entry, terminal differentiation, and wound repair [64] TRPV6 KO have impaired skin barrier, decreased calcium content [65] |

||

| TRPA1 | Increased barrier regeneration [25] Increased calcium entry [24] Modulate differentiation [66] Proinflammation and enhanced contact hypersensitivity [27] TRPA1 KO have decreased response to urushiol [28] |

||

| TRPCs (TRPC1, 4, 5, 6, 7) | Expressed majorly in differentiated keratinocytes [42,67] TRPC1/4: keratinocyte differentiation [44] TRPC6: antiproliferation and induces differentiation [45] Darier’s disease: TRPC1-mediated calcium entry is impaired [26,46] |

Myofibroblast transformation: TRPC6 [68] Impaired calcium entry in keratinocytes from patients with psoriasis [69] TPRC6-induced calcium in keratinocytes from actinic keratosis inhibits cell proliferation and induces differentiation [70] |

Figure 2.

Skin is comprised of epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. In addition to the expression in neurons and nerve endings, TRP channels are also expressed in non-neuron cells in skin. TRPV1 and TRPV3 are expressed in keratinocytes of epidermis and hair apparatus. TRPV1 and TRPV3 inhibit proliferation, induce terminal differentiation, induce apoptosis, and promote inflammation. Activation of TRPV4, 6, and TRPA1 promotes regeneration of the severed skin barriers. TRPA1 also enhances responses in contact hypersensitivity. TRPCs in keratinocytes involve in epidermal differentiation. TRPMs are involved in the pigment production from melanocytes. Not only act in sensory processing, TRP channels also contribute to epidermal differentiation, proliferation, barrier integration, skin regeneration, and cutaneous immune responses.

Regulation of TRPV1 in itch perception

Itch is defined as an unpleasant sensation to provoke scratching [1]. Itch signals are sensed in the skin and relayed to dorsal root ganglion, contralateral spinothalamic tract, thalamus and brain cortex. A subset of TRPV1 expressing sensory neurons, also known as pruritoceptive neurons [2], play an important role in the development of itch. In fact, not only neuron cells but also non neuron epidermal keratinocytes express TRPV1. In patients with prurigo nodularis, a skin disease with intense pruritus, TRPV1 expression is increased in the epidermal keratinocytes [3].

Interestingly, certain endogenous molecules that promote TRPV1 activity (including ATP, prostaglandins and histamine) are also potent pruritogens [2,4]. In humans, histamine-induced itch is mediated, at least in part, by TRPV1 [5]. In line with the data, TRPV1 knockout mice have impaired scratching behavior induced by histamine [6]. Intriguingly, depletion of TRPV1 expressing neurons by capsaicin is associated with intense itch, scratching, and ulcers [7]. These data suggest that TPRV1 might be involved in the perception of itch, however, more neurological and physiological data is warranted.

Role of TRPV1 in the control of skin growth, skin cell survival and cutaneous inflammation

TRPV1 is expressed in a variety of skin cells, including epidermal keratinocytes, mast cells, Langerhans cells, and sebocytes. TRPV1 mostly shows primarily growth-inhibitory functions in the epidermis. TRPV1 is known to regulate keratinocytes growth and differentiation. In cultured keratinocytes, TRPV1-mediated calcium entry inhibits cell proliferation and enhances apoptosis [8,9]. TRPV1 activation by capsaicin regulates the epidermal permeability barrier in vivo [10].

In terms of inflammation, TRPV1 activation by capsaicin in human epidermal keratinocytes causes release of several pro-inflammatory cytokines [8]. UV irradiation increases TRPV1 expression in human skin [11]. TRPV1 in keratinocytes mediates the UV-induced production of MMP1 [12], an enzyme that is implicated in skin inflammation and wound repair. These findings in TRPV1 suggest that TRPV1 modulators may be beneficial in the treatment of several diseases, including photodermatosis, acne vulgaris, and hair disorders.

Regarding to hair morphogenesis, capsaicin induces TRPV1 activation, inhibiting hair shaft elongation and inducing catagen regression. In vivo study showed that TRPV1 activation was associated with differential gene expressions and differential production of cytokines and growth factors, many of which control hair growth in human [9]. In mice, TRPV1 defected mice have impaired hair cycles due to delayed catagen phase [13]. In vitro, TRPV1 activation in human SZ95 sebocytes inhibits sebum production through alternation of genes of lipid homeostasis [14].

TRPV3

TRPV3 is highly expressed in cutaneous keratinocytes [15]. In mice, TRPV3 enhances regeneration of epidermal barrier formation and promotes morphogenesis of hair apparatus. This may occur through the formation of a signaling complex between TRPV3 and the EGFR [16]. Consistent with this concept, TRPV3 knockout mice demonstrated hair abnormalities, including wavy hair coat and curly whiskers [16,17]. On the other hand, constitutively active gain-of-function mutation Trpv3Gly573Ser causes loss of hair and atopic-like dermatitis [18]. TRPV3 activation in organotypic cultures of human hair follicles impairs hair sheath prolongation [19], suggesting the potential pharmaceutical targeting of TRPV3 in the treatment of hypertrichosis and alopecia.

In terms of skin inflammation. TRPV3 activation in keratinocytes induces the release of several pro-inflammatory mediators [20]. The gain-of-function mutation Trpv3Gly573Ser mice develop atopic-like skin disease [18,21]. Furthermore, conditional Trpv3Gly573Ser transgenic mice also demonstrate intense scratching. These evidences suggest that TRPV3 channels may contribute to the different kinds of dermatitis through release of several pro-inflammatory mediators [22].

TRPA1

Skin irritants such as mustard oil, nicotine, and cinnamaldehye, could activate TRPA1 [23]. Analogous to TRPVs, TRPA1 activation by cold or chemicals enhances the regeneration of skin barrier, along with an increase in intracellular calcium [24]. On the other hand, TRPA1 inhibition markedly impairs the recovery of skin barrier [25]. In terms of skin inflammation, TRPA1 activation by cinnamaldehyde application induces skin inflammation through release of Substance P [26]. Contact hypersensitivity reaction is impaired when a TRPA1 antagonist, HC030031, is given [27]. In parallel, TRPA1-defected mice showed an diminished skin inflammation and contact dermatitis caused by oxazolone and urushiol [27,28].

TRPMs

Melanocytes play an important role in the production of melanin, which is important in the intrinsic defense of skin against UV. Furthermore, the most notorious skin cancer with awful prognosis, is the malignant melanoma developed from abnormal clones of melanocytes. TRPM (melastatin TRP) channels control several physiological functions in melanocytes. Human melanocytes express TRPM1, which mediates the production of melanins [29,30]. In melanoma cells, TRPM1 channels are pro-apoptotic [31]. In tissues, TRPM1 expressions are decreased in the samples from metastatic melanoma [32,33]. The miRNA211, coded by an intron of TRPM1, may mediate its tumour-promoting effect [34]. Because of its pro-apoptotic effects, many of the researchers and studies suggested that TRPM1 may serve as a good prognostic marker for metastatic melanoma. For TRPM2, overexpression of wild-type TRPM2 in melanoma cell cultures induces apoptosis [35]. For TRPM7, decreased and/or faulty TRPM7 production leads to impaired melanocytic differentiation [36], which can result in vitiligo, a de-pigmented skin disease with spontaneous loss of epidermal melanocytes.

TRPM8, analogous to TRPA1, can be activated by cold stimuli and several chemicals, such as menthol, eucalyptol, icilin [15,37,38]. TRPM8 gene is also expressed in melanoma cells and tissues. TRPM8 activation in human melanoma cells suppresses cell viability, possible due to calcium-dependent cell death [39,40]. In addition to its role in melanocytes, TRPM8 also regulates the barrier function of epidermal keratinocytes. Topical application of TRPM8 activator WS12 in mice accelerated barrier repair [41], suggesting TRPM8 may be also involved in regulating epidermal homeostasis.

TRPCs

In keratinocytes, not only TRPV1 and TRPV3 are expressed but also other TRP channels. These channels include TRPC1, TRPC4, TPRV4, TRPV5, TRPA1, TRPM8 [42,43]. The detailed functions of these TRP channels remains largely uncertain but they may be involved in the regulation of ordered epidermal differentiation, barrier functions, and abnormal transformation [44,45]. In basal cell carcinoma, the most common skin cancer, TRPC1 and TRPC4 are absent [44]. In Darier’s disease, a disease of abnormal differentiation and keratinization by mutations in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ ATPase ATP2A2 (protein SERCA2), the TRPC1 is overexpressed [46].

The talk between keratinocytes and nerve endings

Since nerve endings apparently penetrate into the epidermis and the epidermis is majorly composed of keratinocytes, it is likely keratinocytes might sense the physical and chemical stimulations and mediate the signal to the surrounding nerve endings as innervated by dorsal root ganglions or neurons. However, little is known about the signaling molecules between keratinocytes and nerve endings. By using a coculture model, Sondersorg et al. reported that ATP serves as the mediating transmitter molecule released from keratinocytes to the neurons [47]. Knockout experiments showed that the opioid receptor pathway regulates skin homeostasis, epidermal nerve fiber regulation, and pathophysiology of itching as revealed by that opioid receptor knockout mice have significantly thinner epidermis and a higher density of free nerve endings than the wild-type counterparts [48]. Keratinocytes irradiated with UV release nitric oxide [49], which was shown to mediate TRPV3-associated thermosensory behaviors in vivo [50]. Finally, the balance between nerve growth factor (NGF), and semaphorin 3A (Sema3A) from keratinocytes was shown to regulate the sensory nerve density in the epidermis [51].

Conclusions

TPRV1 in nerve endings and neurons is involved in the itch perception. TRPV1 and TRPV3 are expressed in kera-tinocytes of epidermis and hair apparatus. TRPV1 and TRPV3 inhibit proliferation, induce terminal differentiation, induce apoptosis, and promote inflammation. Activation of TRPV4, 6, and TRPA1 promotes regeneration of the severed skin barriers. Besides, TRPA1 activation enhances responses in contact hypersensitivity. TRPCs in keratinocytes involve in epidermal differentiation. In diseases with pertubered differentiation such as actinic keratosis, psoriasis, and Darier’s disease, the expression of TRPCs are altered. TRPMs are involved in the pigment production from melanocytes and they might provide significant prognosis markers in patients with metastatic melanoma. Not only act in sensory processing, TRP channels also contribute to epidermal differentiation, proliferation, barrier integration, skin regeneration, and cutaneous immune responses. In diseases with abnormal functions and expressions of TRP channels, TRP channels might be good therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council, Taipei, Taiwan (NSC 99-2314-B-037-007-MY3, NSC 102-2314-B-037-015, MOST 103-2314-B-182A-020), and Chang Gung Medical Research Program (CMRPG8C0821 and CMRPG8D1541).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interests.

Author Contributions

H. J.-C. collected, reviewed the literatures, and drafted the manuscript. L. C.-H. edited the manuscript and approved the final form.

References

- 1.Lee CH, Chuang HY, Shih CC, Jong SB, Chang CH, Yu HS. Transepidermal water loss, serum IgE and beta-endorphin as important and independent biological markers for development of itch intensity in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1100–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paus R, Schmelz M, Biro T, Steinhoff M. Frontiers in pruritus research: scratching the brain for more effective itch therapy. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1174–1186. doi: 10.1172/JCI28553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stander S, Moormann C, Schumacher M, Buddenkotte J, Artuc M, Shpacovitch V, Brzoska T, Lippert U, Henz BM, Luger TA, Metze D, Steinhoff M. Expression of vanilloid receptor subtype 1 in cutaneous sensory nerve fibers, mast cells, and epithelial cells of appendage structures. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.0178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biro T, Toth BI, Marincsak R, Dobrosi N, Geczy T, Paus R. TRP channels as novel players in the pathogenesis and therapy of itch. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:1004–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisshaar E, Heyer G, Forster C, Handwerker HO. Effect of topical capsaicin on the cutaneous reactions and itching to histamine in atopic eczema compared to healthy skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290:306–311. doi: 10.1007/s004030050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shim WS, Tak MH, Lee MH, Kim M, Koo JY, Lee CH, Oh U. TRPV1 mediates histamine-induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12-lipoxygenase. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2331–2337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4643-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrillo P, Camacho M, Manzo J, Martinez-Gomez M, Salas M, Pacheco P. Cutaneous wounds produced by capsaicin treatment of newborn rats are due to trophic disturbances. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1998;20:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodo E, Biro T, Telek A, Czifra G, Griger Z, Toth BI, Mescalchin A, Ito T, Bettermann A, Kovacs L, Paus R. A hot new twist to hair biology: involvement of vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1/TRPV1) signaling in human hair growth control. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:985–998. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toth BI, Dobrosi N, Dajnoki A, Czifra G, Olah A, Szollosi AG, Juhasz I, Sugawara K, Paus R, Biro T. Endocannabinoids modulate human epidermal keratinocyte proliferation and survival via the sequential engagement of cannabinoid receptor-1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid- 1. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1095–1104. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denda M, Sokabe T, Fukumi-Tominaga T, Tominaga M. Effects of skin surface temperature on epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:654–659. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee YM, Kim YK, Chung JH. Increased expression of TRPV1 channel in intrinsically aged and photoaged human skin in vivo. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YM, Kim YK, Kim KH, Park SJ, Kim SJ, Chung JH. A novel role for the TRPV1 channel in UV-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 expression in HaCaT cells. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:766–775. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biro T, Bodo E, Telek A, Geczy T, Tychsen B, Kovacs L, Paus R. Hair cycle control by vanilloid receptor-1 (TRPV1): evidence from TRPV1 knockout mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1909–1912. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toth BI, Geczy T, Griger Z, Dozsa A, Seltmann H, Kovacs L, Nagy L, Zouboulis CC, Paus R, Biro T. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 signaling as a regulator of human sebocyte biology. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:329–339. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peier AM, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Moqrich A, Earley TJ, Hergarden AC, Story GM, Colley S, Hogenesch JB, McIntyre P, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. A heat-sensitive TRP channel expressed in keratinocytes. Science. 2002;296:2046–2049. doi: 10.1126/science.1073140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng X, Jin J, Hu L, Shen D, Dong XP, Samie MA, Knoff J, Eisinger B, Liu ML, Huang SM, Caterina MJ, Dempsey P, Michael LE, Dlugosz AA, Andrews NC, Clapham DE, Xu H. TRP channel regulates EGFR signaling in hair morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Cell. 2010;141:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moqrich A, Hwang SW, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Murray AN, Spencer KS, Andahazy M, Story GM, Patapoutian A. Impaired thermosensation in mice lacking TRPV3, a heat and camphor sensor in the skin. Science. 2005;307:1468–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1108609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshioka T, Imura K, Asakawa M, Suzuki M, Oshima I, Hirasawa T, Sakata T, Horikawa T, Arimura A. Impact of the Gly573Ser substitution in TRPV3 on the development of allergic and pruritic dermatitis in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:714–722. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borbiro I, Lisztes E, Toth BI, Czifra G, Olah A, Szollosi AG, Szentandrassy N, Nanasi PP, Peter Z, Paus R, Kovacs L, Biro T. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid-3 inhibits human hair growth. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1605–1614. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu H, Delling M, Jun JC, Clapham DE. Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:628–635. doi: 10.1038/nn1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asakawa M, Yoshioka T, Matsutani T, Hikita I, Suzuki M, Oshima I, Tsukahara K, Arimura A, Horikawa T, Hirasawa T, Sakata T. Association of a mutation in TRPV3 with defective hair growth in rodents. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2664–2672. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran MM, McAlexander MA, Biro T, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:601–620. doi: 10.1038/nrd3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordt SE, Bautista DM, Chuang HH, McKemy DD, Zygmunt PM, Hogestatt ED, Meng ID, Julius D. Mustard oils and cannabinoids excite sensory nerve fibres through the TRP channel ANKTM1. Nature. 2004;427:260–265. doi: 10.1038/nature02282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsutsumi M, Denda S, Ikeyama K, Goto M, Denda M. Exposure to low temperature induces elevation of intracellular calcium in cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1945–1948. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denda M, Tsutsumi M, Goto M, Ikeyama K, Denda S. Topical application of TRPA1 agonists and brief cold exposure accelerate skin permeability barrier recovery. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1942–1945. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiba T, Tamai T, Sahara Y, Kurohane K, Watanabe T, Imai Y. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 activation enhances hapten sensitization in a T-helper type 2-driven fluorescein isothiocyanate-induced contact hypersensitivity mouse model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;264:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B, Escalera J, Balakrishna S, Fan L, Caceres AI, Robinson E, Sui A, McKay MC, McAlexander MA, Herrick CA, Jordt SE. TRPA1 controls inflammation and pruritogen responses in allergic contact dermatitis. FASEB J. 2013;27:3549–3563. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-229948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devi S, Kedlaya R, Maddodi N, Bhat KM, Weber CS, Valdivia H, Setaluri V. Calcium homeostasis in human melanocytes: role of transient receptor potential melastatin 1 (TRPM1) and its regulation by ultraviolet light. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C679–687. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00092.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oancea E, Vriens J, Brauchi S, Jun J, Splawski I, Clapham DE. TRPM1 forms ion channels associated with melanin content in melanocytes. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo H, Carlson JA, Slominski A. Role of TRPM in melanocytes and melanoma. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:650–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duncan LM, Deeds J, Cronin FE, Donovan M, Sober AJ, Kauffman M, McCarthy JJ. Melastatin expression and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:568–576. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller AJ, Du J, Rowan S, Hershey CL, Widlund HR, Fisher DE. Transcriptional regulation of the melanoma prognostic marker melastatin (TRPM1) by MITF in melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:509–516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazar J, DeYoung K, Khaitan D, Meister E, Almodovar A, Goydos J, Ray A, Perera RJ. The regulation of miRNA-211 expression and its role in melanoma cell invasiveness. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orfanelli U, Wenke AK, Doglioni C, Russo V, Bosserhoff AK, Lavorgna G. Identification of novel sense and antisense transcription at the TRPM2 locus in cancer. Cell Res. 2008;18:1128–1140. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNeill MS, Paulsen J, Bonde G, Burnight E, Hsu MY, Cornell RA. Cell death of melanophores in zebra-fish trpm7 mutant embryos depends on melanin synthesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2020–2030. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature. 2002;416:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bautista DM, Siemens J, Glazer JM, Tsuruda PR, Basbaum AI, Stucky CL, Jordt SE, Julius D. The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature. 2007;448:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nature05910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slominski A. Cooling skin cancer: menthol inhibits melanoma growth. Focus on “TRPM8 activation suppresses cellular viability in human melanoma”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C293–295. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00312.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamura H, Ugawa S, Ueda T, Morita A, Shimada S. TRPM8 activation suppresses cellular viability in human melanoma. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C296–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00499.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denda M, Tsutsumi M, Denda S. Topical application of TRPM8 agonists accelerates skin permeability barrier recovery and reduces epidermal proliferation induced by barrier insult: role of cold-sensitive TRP receptors in epidermal permeability barrier homoeostasis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:791–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bezzerides VJ, Ramsey IS, Kotecha S, Greka A, Clapham DE. Rapid vesicular translocation and insertion of TRP channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:709–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai S, Fatherazi S, Presland RB, Belton CM, Roberts FA, Goodwin PC, Schubert MM, Izutsu KT. Evidence that TRPC1 contributes to calcium-induced differentiation of human keratinocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-0001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck B, Lehen’kyi V, Roudbaraki M, Flourakis M, Charveron M, Bordat P, Polakowska R, Prevarskaya N, Skryma R. TRPC channels determine human keratinocyte differentiation: new insight into basal cell carcinoma. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:492–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller M, Essin K, Hill K, Beschmann H, Rubant S, Schempp CM, Gollasch M, Boehncke WH, Harteneck C, Muller WE, Leuner K. Specific TRPC6 channel activation, a novel approach to stimulate keratinocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33942–33954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801844200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pani B, Cornatzer E, Cornatzer W, Shin DM, Pittelkow MR, Hovnanian A, Ambudkar IS, Singh BB. Up-regulation of transient receptor potential canonical 1 (TRPC1) following sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2 gene silencing promotes cell survival: a potential role for TRPC1 in Darier’s disease. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4446–4458. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sondersorg AC, Busse D, Kyereme J, Rothermel M, Neufang G, Gisselmann G, Hatt H, Conrad H. Chemosensory information processing between keratinocytes and trigeminal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:17529–17540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.499699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bigliardi-Qi M, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Pfaltz K, Bady P, Baumann T, Rufli T, Kieffer BL, Bigliardi PL. Deletion of mu- and kappa-opioid receptors in mice changes epidermal hypertrophy, density of peripheral nerve endings, and itch behavior. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1479–1488. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seiffert K, Granstein RD. Neuropeptides and neuroendocrine hormones in ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression. Methods. 2002;28:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyamoto T, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin. Nat Commun. 2011;2:369. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tominaga M, Takamori K. An update on peripheral mechanisms and treatments of itch. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:1241–1247. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inoue K, Koizumi S, Fuziwara S, Denda S, Denda M. Functional vanilloid receptors in cultured normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:124–129. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bodo E, Kovacs I, Telek A, Varga A, Paus R, Kovacs L, Biro T. Vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1) is widely expressed on various epithelial and mesenchymal cell types of human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:410–413. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li WH, Lee YM, Kim JY, Kang S, Kim S, Kim KH, Park CH, Chung JH. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 mediates heat-shock-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2328–2335. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jain A, Bronneke S, Kolbe L, Stab F, Wenck H, Neufang G. TRP-channel-specific cutaneous eicosanoid release patterns. Pain. 2011;152:2765–2772. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li HJ, Kanazawa N, Kimura A, Kaminaka C, Yonei N, Yamamoto Y, Furukawa F. Severe ulceration with impaired induction of growth factors and cytokines in keratinocytes after trichloroacetic acid application on TRPV1-deficient mice. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:614–621. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee YM, Kang SM, Chung JH. The role of TRPV1 channel in aged human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;65:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yun JW, Seo JA, Jang WH, Koh HJ, Bae IH, Park YH, Lim KM. Antipruritic effects of TRPV1 antagonist in murine atopic dermatitis and itching models. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1576–1579. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bode AM, Cho YY, Zheng D, Zhu F, Ericson ME, Ma WY, Yao K, Dong Z. Transient receptor potential type vanilloid 1 suppresses skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:905–913. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cals-Grierson MM, Ormerod AD. Nitric oxide function in the skin. Nitric Oxide. 2004;10:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Radtke C, Sinis N, Sauter M, Jahn S, Kraushaar U, Guenther E, Rodemann HP, Rennekampff HO. TRPV channel expression in human skin and possible role in thermally induced cell death. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:150–159. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318203350c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin Z, Chen Q, Lee M, Cao X, Zhang J, Ma D, Chen L, Hu X, Wang H, Wang X, Zhang P, Liu X, Guan L, Tang Y, Yang H, Tu P, Bu D, Zhu X, Wang K, Li R, Yang Y. Exome sequencing reveals mutations in TRPV3 as a cause of Olmsted syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sokabe T, Fukumi-Tominaga T, Yonemura S, Mizuno A, Tominaga M. The TRPV4 channel contributes to intercellular junction formation in keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18749–18758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lehen’kyi V, Vandenberghe M, Belaubre F, Julie S, Castex-Rizzi N, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Acceleration of keratinocyte differentiation by transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV6) channel activation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(Suppl 1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bianco SD, Peng JB, Takanaga H, Suzuki Y, Crescenzi A, Kos CH, Zhuang L, Freeman MR, Gouveia CH, Wu J, Luo H, Mauro T, Brown EM, Hediger MA. Marked disturbance of calcium homeostasis in mice with targeted disruption of the Trpv6 calcium channel gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:274–285. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atoyan R, Shander D, Botchkareva NV. Non-neuronal expression of transient receptor potential type A1 (TRPA1) in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2312–2315. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fatherazi S, Presland RB, Belton CM, Goodwin P, Al-Qutub M, Trbic Z, Macdonald G, Schubert MM, Izutsu KT. Evidence that TRPC4 supports the calcium selective I(CRAC)-like current in human gingival keratinocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:879–889. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davis J, Burr AR, Davis GF, Birnbaumer L, Molkentin JD. A TRPC6-dependent pathway for myofibroblast trans-differentiation and wound healing in vivo. Dev Cell. 2012;23:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leuner K, Kraus M, Woelfle U, Beschmann H, Harteneck C, Boehncke WH, Schempp CM, Muller WE. Reduced TRPC channel expression in psoriatic keratinocytes is associated with impaired differentiation and enhanced proliferation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woelfle U, Laszczyk MN, Kraus M, Leuner K, Kersten A, Simon-Haarhaus B, Scheffler A, Martin SF, Muller WE, Nashan D, Schempp CM. Triterpenes promote keratinocyte differentiation in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo: a role for the transient receptor potential canonical (subtype) 6. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:113–123. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]