Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes (PNSs) occur with increased frequency in patients with cancer and almost always antedate its diagnosis. These syndromes comprise a heterogeneous group of cancer-related neurologic diseases, and they may affect any part of the nervous system. The simultaneous involvement of different areas of the nervous system by the paraneoplastic process is not unusual. Until date, this is the first report of concurrent development of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) and paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) associated with the advanced ovarian cancer and anti-Yo antibodies following hepatitis B (HB) vaccination. The cause of most PNS is believed to be an immune response against neuronal proteins expressed by the tumor.[1]

A 37-year-old woman (unmarried, nulliparous) presented with 45 days of mental and behavior change who had a history of twice HB vaccination with an interval of 2 months. She developed symptoms of worsening dizziness and vertigo few hours after receiving the second dose of the HB vaccine, then followed by severe vomiting and double vision. Few days later, the patient developed rapidly progressive ataxia, involuntary movements of arms, slurred speech, anxiety, depression, agitation, irritability, aggressive behavior, dysarthria, dysphagia, choking while drinking, hypomnesia, and sleeping disturbance.

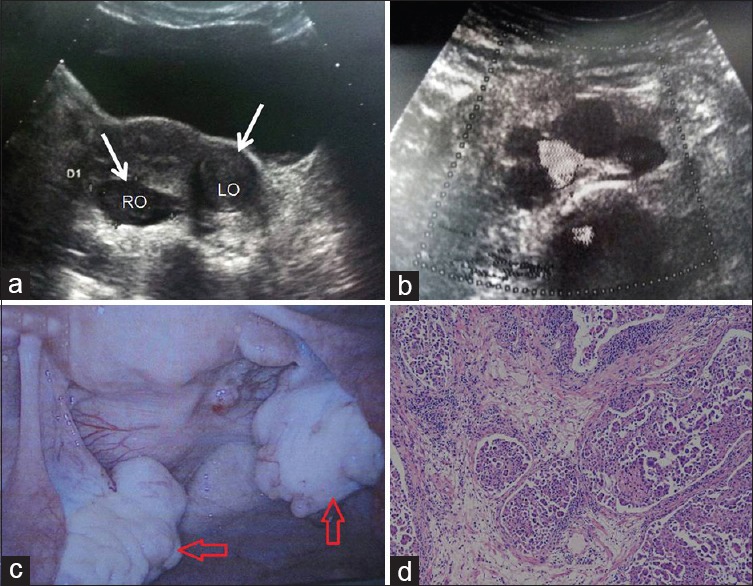

In February 2012, she was referred to our hospital for her continued physical and mental decline. Neurological exam was significant for ataxia and cerebellar dysfunction. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not reveal any mass lesion or signs of cerebellar atrophy, stroke, or cerebellitis. Electroencephalogram (EEG) registered an asymmetric slow wave with epileptiform discharges on the right temporal lobe. A lumbar puncture yielded clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with normal open pressure and showed inflammatory changes (pleocytosis, 6000/ml, 95% lymphocyte, 5% monocytes and elevated immunoglobulin). Paraneoplastic antibody testing revealed that anti-Yo antibodies were positive in both CSF and serum. Concurrently, her serum Cancer Antigen (CA125) increased from 415 U/ml to 2752 U/ml (normal range <35) after an interval of 4 weeks, several other tumor markers, including CA242, CA72-4, and CA15-3 were also found to be slightly elevated. Both ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral adnexal cystic-solid masses and several enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes [Figure 1a and 1b].

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography, exploratory laparoscopy and pathological findings of the patient. Abdominal ultrasound inspection showed bilateral adnexal cystic-solid masses (a) and several enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes (b) Exploratory laparoscopy showed bilateral adnexal solid masses (c) Pathological findings of high-grade ovarian serous papillary cystadenocarcinoma (Red arrow) (d) (H and E staining ×200).

Exploratory laparoscopy [Figure 1c] and biopsy indicated pelvic disseminated malignant lesions. Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of high-grade ovarian serous papillary cystadenocarcinoma [Figure 1d]. Her serum CA125 decreased to normal, and psychiatric symptoms had dramatic improvement after three courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with paclitaxel and carboplatin. Then, the patient underwent an interval cytoreductive surgery, and complete surgical resection of all visible tumor masses was achieved. Microscopic examination showed periaortic and internal iliac lymph nodes (8/25) metastasis. The patient's surgical-pathological staging was IIIc according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system 2009. She should receive at least 6 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy postoperatively. However, the patient was only treated with two cycles of the same regimen chemotherapy, and her family gave up the following treatment due to the serious adverse effects of chemotherapy.

Until date, she has been alive for 38 months without any recurrent evidence. Her mental symptoms continue to improve gradually, and she is able to have simple language communication with her family. However, she still could not stand up on her own.

The acute onset of a rapidly progressive vertigo and ataxia in this patient showed a close chronological correlation with her HB vaccination, the quantification of anti-HBs serum level was 211.09 mIU/ml (normal range, 0–10), which suggested that the patient was a responder to HB vaccine and the immunization might have triggered the PNS. Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis may occur in patients with lung adenocarcinoma post influenza-vaccination.[2] Until date, no postvaccinal PCD and PLE have been reported in healthy people or in patients with the tumor.

We hypothesized that the classical PNS in this patient was triggered or exacerbated through a postvaccinal aberrant autoimmunity. The triggering mechanism of autoimmune disease after a vaccination might be classified as an antigen-specific or an antigen nonspecific process in which the vaccination induces cytokines and aberrant expression of major histo-compatibility complex class II and further facilitates autoantigen expression and autoreactive T-cell activation that precipitates into a cascade of self-propagating autoimmunity.[3]

The pathogenesis of PNS is incompletely understood, but it is believed to be associated with antibody and T-cell responses against the expression of shared epitopes in the nervous system and the tumors.[4] The fact that this patient did not have such a postvaccinal response before suggests an altered adaptive immunity in the presence of an ovarian tumor. In addition, the PNS improved simultaneously with remission of the ovarian tumor.

The complex diagnosis of paraneoplastic syndromes, rarely pathognomonic for a certain paraneoplastic etiology, emphasizes the importance of timely detection of the tumor for the most probable anatomical location using the most sensitive diagnostic measures available. PNS is defined by the presence of cancer and exclusion of other known causes of the neurological symptoms. Antibodies appear to be crucial but not sufficient to cause neurologic dysfunction alone on its own. Given the well-known association between anti-Yo antibodies and ovarian cancer, this important finding would guide the search for the tumor. However, in approximately 40% of patients, no antibodies are identified.[5] Further studies are required to characterize the mechanisms leading to neuronal death in PNS.

The diagnosis of PCD and PLE may be challenging, and the clinician must first eliminate possible metabolic, infectious, and neurotoxic etiologies as well as metastatic disease. CT and MRI imaging are important complementary studies to rule out other neurological complications of cancer, but they are normal or nonspecific in the early stages of PCD, as the disease progresses, cerebellar atrophy develops. In our case, there is no characteristic MRI. The EEG often demonstrates uni- or bilateral temporal lobe epileptic discharges or slow background activity.

Recent literatures have reported that the patients without antibodies have a better response to treatment compared to patients with antibodies. Therefore, laboratory assessment for these onco-neural antibodies not only serves as a diagnostic modality but also aids in predicting prognosis. In patients with PNS, the neurological symptoms and survival vary with both the type of associated onco-neural antibody as well as the type of tumor.

It must be emphasized that PLE occurs at an early stage of the disease development and, therefore, the detection of paraneoplastic PLE can lead to a quicker identification of the underlying malignancy and a better outcome. PLE is reversible with the prompt surgical management of the primary tumor and chemotherapy while PCD is usually irreversible. Consequently, management of the primary tumor is essential to stave off disease progression or metastatic involvement.

In conclusion, we have attempted to throw some light on the potential causal relationship between HB vaccination and PNS. The fact that this patient was a responder to HB vaccine would strengthen the association between vaccination and paraneoplastic syndrome. Female patients who present with symptoms of PNS should be thoroughly screened for gynecological malignancy. Early awareness of PNS and timely therapies are important for the good prognosis of patients. In view of this, in addition to neurologist's need continuous learning, relevant professional physicians also need to constantly update for interdisciplinary understanding of the so-called “marginal” disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yi Cui

REFERENCES

- 1.Graus F, Delattre JY, Antoine JC, Dalmau J, Giometto B, Grisold W, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1135–40. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu YJ, Lai ML, Huang CW. Reversible postvaccination paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Neurosci. 2010;120:792–5. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2010.520380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pou MA, Diaz-Torne C, Vidal S, Corchero C, Narvaez J, Nolla JM, et al. Development of autoimmune diseases after vaccination. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14:243–4. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318181b496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat R, Steinman L. Innate and adaptive autoimmunity directed to the central nervous system. Neuron. 2009;64:123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalmau J, Gonzalez RG, Lerwill MF. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 4-2007. A 56-year-old woman with rapidly progressive vertigo and ataxia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:612–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc069035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]