INTRODUCTION

Augmentation rhinoplasty is the most common rhinoplasty procedure in the Asian population. Asian nose is characterized by a broad low dorsum, decreased tip projection, thick skin, abundant subcutaneous tissue, and a weak cartilage framework.[1] As a result, the patients often request a higher nasal dorsum and a more projected tip. Various materials have been reported for augmentation rhinoplasty. Alloplastic implants are widely used in Asia, for good esthetic outcomes and no donor site morbidity. Silicone and Gore-Tex are the most common used alloplastic implants, and can achieve good results. However, the limited biocompatibility may cause allergic reactions, extrusion, displacement, and infection.[2] Costal cartilage for abundant in quality can be carved in a variety of shapes. It is a useful graft for patients requiring substantial augmentation and revision rhinoplasty.

In 1889, Von Mangoldt first reported the autogenous costal cartilage in rhinoplasty.[3] The main drawback of solid costal cartilage is the unpredictable warping over time. In addition, it is not easy for inexperienced surgeons to carve the cartilage into the precise shape. In 1954, Peer first reported the diced cartilage for reconstructive surgery to avoid the problem of warping. Thin as 0.5–1.0 mm in size diced cartilage could be easily malleable with no possibility of warping. Based on previous studies, we modified the diced cartilage for rhinoplasty. Here we present our experience using bare diced cartilage combined with slim strips in augmentation rhinoplasty in an easy way.

METHODS

From July of 2013 to January of 2014, 22 patients underwent diced costal cartilage for nasal augmentation in Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College.

Surgical techniques

Cartilage preparation

The procedure was carried out under local anesthesia with an intravenous sedation. The cartilage was harvested from the 7th rib on the right side through a 2 to 3.0 cm incision, leaving the perichondrium in the donor site. The harvested cartilage was 2.5–4.0 cm in length, with a volume of 2 ml around according to the original nasal shape and the aesthetic goal. A long piece of cartilage was preserved and carved into a series of 2- to 3-mm wide strips, a little bit longer than the length of the columella, which would function as the strut to provide the essential support for the tip projection and maintains the shape of the columella. The remnant cartilage was cut longitudinally into 0.5- to 1-mm laminates with a long blade, and then into long strips. Then, the strips were cut transversally into 0.5-mm cubes, filled into a 1-ml syringe with the hub cut off and compacted with the plunger to eliminate the possible dead space among the cartilage cubes.

Nasal augmentation rhinoplasty

The procedure of the cartilage grafting proceeded via an endonasal approach with the recipient pocket dissected through a 1 cm unilateral marginal incision. The dissection along the dorsum was carefully carried out in the subperiosteal plane. The depressor septi nasi was released by blunt dissection in patients with a drooping nasal tip. A relatively tight pocket was necessary to avoid the dispersion or displacement of the diced cartilage. Once the dissection was done, the syringe filled with cartilage was inserted directly to the radix. With the plunger pushed slowly while the syringe was withdrawn, the pocket was filled with cartilage fragments evenly along the full length of the nasal dorsum. Afterward, two to three pieces of strips were inserted into the columella until the expected tip projection was obtained. The incision was closed with 6-0 nylon suture in simple interrupted fashion. A thermoplastic mold was placed over the nasal dorsum and left for 1-week. No antibiotics were administrated systematically, or for immersion of the graft.

Patients needed to come for a clinical visit on the 1st, 3rd and 7th day postoperatively. Sutures, as well as the mold, were removed on the 7th day. Standardized photographs were taken at the preoperative, 3 and 6 months of postoperative periods. Postoperative result was graded by the patient's self-evaluation of the nasal appearance with a 5-point scale (1: Much worse, 2: Worse, 3: Fair, 4: Improved, and 5: Much improved). Complications including warping, infection, absorption, nasal dysfunction, and donor-site morbidity were recorded.

RESULTS

All patients were followed up for at least 6 months postoperative, with the average follow-up time of 8.9 months (range: 6.0–12.0 months). All the patients were female, with an average age of 26.8 years (range: 18.0 –42.0 years). There were 12 primary cases and 10 revision cases, including silicone used in 7 cases and polyacrylamide hydrogel in 3 cases of previous surgery.

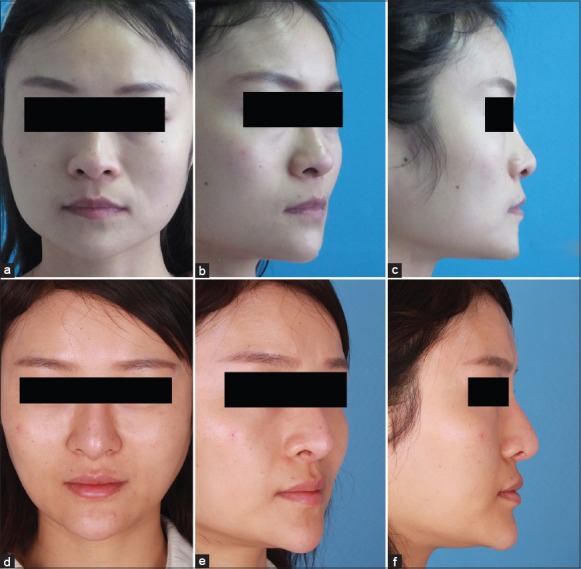

All patients reported improved or better results [Figure 1] except for one patient complained of overcorrection. The revision surgery was performed by shaving and extracting the redundant cartilage 6 months after the primary operation. The patient was satisfied with the final result. Supratip step-off was observed in one patient on the 7th day after surgery and corrected by external reshaping and continued fixation of the mold without operation. No warping, infection, irregularity, absorption, airway obstruction, or donor-site morbidity were observed.

Figure 1.

A 34-year-old female patient with a low and short nose preoperatively (a-c) underwent a primary rhinoplasty and dorsal augmentation with the diced cartilage graft. The 6-month postoperative photos (d-f) showed an improved appearance. The patient has signed the consent form for publication.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have proved that the costal cartilage is the preferred graft for performing substantial augmentation, especially for revision cases.[4] Diced cartilage carries a minimal risk of warping, and can be easily molded once the graft is in the good plane. Diced cartilage also has the advantage of easy revisions and handling postoperatively. To stabilize the diced cartilage fragment, Daniel used autologous deep temporal fascia as a wrapping material in diced rhinoplasty, without absorption. The problem associated with fascia is that, it may be difficult to precisely assess the final dorsal height due to unintentional over or under correction for the bulk of the fascial graft. In addition, the morbidity of deep temporal fascia harvestings, such as local scar, and alopecia, should be considered. Furthermore, it remains controversial so far on the viability of cartilage wrapped in fascia according to the animal experiments and histological examination. Previous literature have stated that the primary reason for using deep temporal fascia served as the scaffold is to prevent the risk of visibility and dispersion of diced cartilage.[5] In our study, bare cartilage cubes were directly injected into the recipient site without fascia sleeve. To avoid the visible irregularity, we recommend the cartilage fragments were diced as fine as 0.5 mm or smaller. To prevent the dispersion, the dissection should be carried out in the subperiosteal plane over the nasal bone. It is necessary to dissect the pocket in a tight way, which allows for better control of shape and contour. Also, the postoperative taping of the thermoplastic mold helps to maintain the nasal dorsal shape. In addition, postoperative close observation and correction in some cases are essential to make sure the cartilage in the normal place.

No visible absorption was observed in all cases. We had one case of overcorrection and expected absorption for aesthetic improvement. However, no substantial changes occurred even after 6 months. Then we had to perform the revision surgery. One patient complained that the supratip step-off on the 7th day after surgery. We think that the step-off was caused by the strengthened bondage of the peripheral fibrous tissue in the supratip portion. In later cases, we dissected the recipient site more widely in this section. For this patient, the supratip step-off was corrected by external adjustment and a prolonged taping of thermoplastic mold.

In conclusion, diced costal cartilage rhinoplasty is a reliable option for primary and revision cases. Closely postoperative observation is required in some cases. Satisfied results can be achieved in a relatively easy way.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by a grant from Peking Union Medical College Characteristic Funding (To Ji-Guang Ma).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Shao Guo

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang TL, Xue ZQ, Yu DS, Zhang HM, Tang XJ, Ma JG. Rhinoplasty in Chinese: Management of lower dorsum and bulbous nasal tip. Chin Med J. 2009;122:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tham C, Lai YL, Weng CJ, Chen YR. Silicone augmentation rhinoplasty in an Oriental population. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000141947.00927.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JS, Khan NA, Song HM, Jang YJ. Intraoperative measurements of harvestable septal cartilage in rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65:519–23. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181d59f95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peer LA. A method to correct saddle nose associated with retracted columella. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;38:477–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel RK. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery: Current techniques and applications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1883–91. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818d2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]