Abstract

Brain edema is a major neurological complication of acute liver failure (ALF) and swelling of astrocytes (cytotoxic brain edema) is the most prominent neuropathological abnormality in this condition. Elevated brain ammonia level has been strongly implicated as an important factor in the mechanism of astrocyte swelling/brain edema in ALF. Recent studies, however, have suggested the possibility of a vasogenic component in the mechanism in ALF. We therefore examined the effect of ammonia on blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity in an in vitro co-culture model of the BBB (consisting of primary cultures of rat brain endothelial cells and astrocytes). We found a minor degree of endothelial permeability to dextran fluorescein (16.2%) when the co-culture BBB model was exposed to a pathophysiological concentration of ammonia (5 mM). By contrast, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a molecule well-known to disrupt the BBB, resulted in an 87% increase in permeability. Since increased neurosteroid biosynthesis has been reported to occur in brain in ALF, and since neurosteroids are known to protect against BBB breakdown, we examined whether neurosteroids exerted any protective effect on the slight permeability of the BBB after exposure to ammonia. We found that a nanomolar concentration (10 nM) of the neurosteroids allopregnanolone (THP) and tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC) significantly reduced the ammonia-induced increase in BBB permeability (69.13 and 58.64%, respectively). On the other hand, we found a marked disruption of the BBB when the co-culture model was exposed to the hepatotoxin azoxymethane (218.4%), but not with other liver toxins commonly used as models of ALF (thioacetamide and galactosamine, showed a 29.3 and 30.67% increase in permeability, respectively). Additionally, THP and THDOC reduced the effect of TAA and galactosamine on BBB permeability, while no BBB protective effect was observed following treatment with azoxymethane. These findings suggest that ammonia does not cause a significant BBB disruption, and that the BBB is intact in the TAA or galactosamine-induced animal models of ALF, likely due to the protective effect of neurosteroids that are synthesized in brain in the setting of ALF. However, caution should be exercised when using azoxymethane as an experimental model of ALF as it caused a severe breakdown of the BBB, and neurosteriods failed to protect against this.

Keywords: Acute liver failure, ammonia, astrocyte swelling, brain edema, blood-brain barrier, hepatotoxins, neurosteroids

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a major clinical complication in patients with severe liver disease. HE in the setting of chronic liver disease (HE Type C or portal-systemic encephalopathy) usually occurs after alcoholic liver cirrhosis (for review, see [1]). HE Type C is characterized by alterations in cognition, consciousness and motor function. The encephalopathy associated with acute liver failure (ALF) occurs following massive liver necrosis, generally due to viral hepatitis (predominantly hepatitis B), hepatic neoplasms, vascular causes or exposure to various hepatotoxins. It presents with the abrupt onset of delirium, seizures, and coma and has an extremely poor prognosis (70% mortality) (for reviews, see [2, 3]) While cerebral edema and associated increased intracranial pressure and brain herniation occur in up to 80% of patients with ALF [2, 4], and represents the most frequent cause of death in these individuals [2, 5, 6], the actual percentage of deaths remains unclear [2, 7]. However, current reports indicate that mortality has decreased in recent years (for review, see [3]).

Swelling of astrocytes (cytotoxic edema) represents the major component of the edema in ALF (for review, see [8]). Swollen astrocytic processes were identified in patients dying with ALF [9, 10]. Magnetic resonance and diffusion-weighted imaging studies in patients with ALF revealed a reduction in the size of the extracellular space, consistent with an intracellular accumulation of water [11, 12]. Animal studies also support the cytotoxic aspect of ALF-related brain edema (for review, see [13]). Further, exposure of rat cerebral cortical slices or organotypic slice cultures from mouse forebrain to 1–10 mM ammonia was shown to induce astrocyte swelling [14, 15]. Additionally, treatment of cultured astrocytes with a pathophysiologically relevant concentration of ammonia (5 mM) was shown to induce cell swelling [8, 16–19]. In aggregate, these findings strongly support that the brain edema in ALF is cytotoxic, principally as a result of astrocyte swelling.

While a generalized breakdown of the BBB (as occurs in vasogenic edema) is not a feature in humans with ALF, a recent study [20] suggested that in patients dying with ALF, the brain edema is vasogenic in origin since there was evidence of tight junctional abnormalities, brain microvessel endothelial cell shrinkage, and a reduction in occluding protein expression. While the reason for BBB breakdown in animal models is not clear, it is possible that liver toxins employed in these studies may have direct toxic effect on components of the BBB that are independent of ALF. We therefore examined to what extent various liver toxins commonly used to induce ALF, contribute to a breakdown of the BBB using an in vitro co-culture model of the BBB. Since increased neurosteroid biosynthesis is known to protect against BBB breakdown [21–24], and increased neurosteroid production has been reported in brains of rats with ALF (for review, see [25]), we also examined whether neurosteroids exert a protective effect on the slight BBB permeability observed after exposure to ammonia and other liver toxins.

Materials and Methods

All chemicals used in the study were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless noted otherwise: thioacetamide (TAA, cat# 163678), ammonium chloride (Cat# A0171), D- (+)-Galactosamine hydrochloride (Cat# G0500), and azoxymethane (Cat# A5486).

Co-culture of brain microvessel endothelial cells and astrocytes

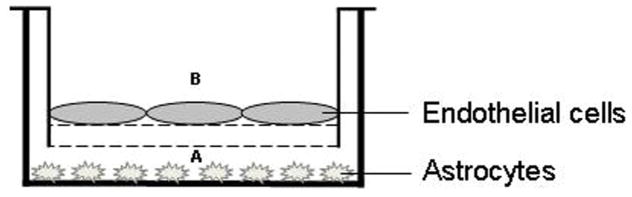

A co-culture model of BBB (containing brain microvessel endothelial cells and astrocytes) was employed to examine the effect of toxins on BBB permeability using a model previously described [26]. Briefly, primary endothelial cells from brain microvessels were seeded on transwell inserts (3.0 mm pore size) (Figure 1). Primary cultures of astrocytes were seeded at the bottom of the transwell inserts. Ammonia and other liver toxins, as well as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a well-known inducer of the BBB breakdown [26], were added to the lower compartment (A) (Figure 1). Endothelial permeability was measured by adding fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (40 kDa) in the lower compartment (A) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml at 37°C for 20 min. Fluorescence was measured in the culture media from the upper compartment (B) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 520 nm.

Figure 1.

Co-culture model of BBB (brain microvessel endothelial cells and astrocytes). Primary cultures of astrocytes were seeded at the bottom of the transwell inserts. Ammonia and other liver toxins, LPS as well as the fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (40 kDa), were added to the lower compartment (A). Fluorescence was measured in the culture media from the upper compartment (B).

Results

Effect of ammonia and LPS on BBB permeability

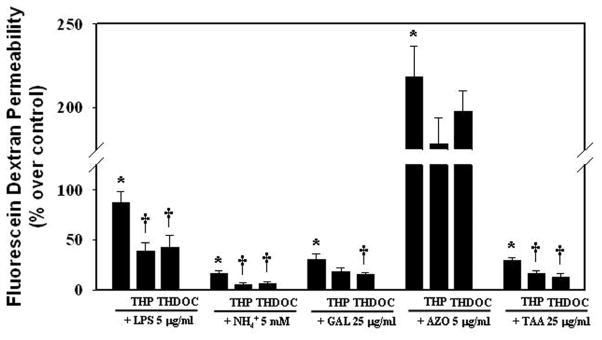

Co-culture of microvessel endothelial cells and astrocytes were treated for 24 h with 5 mM ammonia (NH4Cl), the concentration detected in brains of experimental animals with ALF [27–29], and the extent of endothelial permeability was measured by adding fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran as noted above in Materials and Methods. Ammonia caused only a slight increase in dextran fluorescein (16.2%) (Figure 2). However, we found a BBB breakdown when co-cultures were exposed to LPS (5 μg/ml) for 24 h (87.1% permeability) (Figure 2). A recent report also describes a slight increase in the paracellular permeability (27%) using cultured endothelial cell line (RBE-4) after exposure to ammonia; however, this culture system did not include astrocytes ([30]).

Figure 2.

Effect of liver toxins on BBB permeability to fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran. Co-culture model of BBB were exposed to LPS, ammonia, galactosamine, azoxymethane and thioacetamide (TAA) for 24 h, with and without the neurosteroids THP and THDOC (10 nM), and the extent of permeability to fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran was determined. Data of all experiments were subjected to analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparisons. *p<0.05 vs. control; †p<0.05 vs. toxins. Error bars, mean ± S.E. THP, allopregnanolone (3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one); THDOC, 3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone/3α, 5α).

Effect of neurosteroids on the ammonia-induced BBB permeability

Since increased neurosteroid biosynthesis has been reported in brains of rats with ALF (for review, see [25]) and neurosteriods are known to protect BBB from breakdown in other conditions [31], we examined whether neurosteroids also exert a protective effect on the slight BBB permeability observed after exposure to ammonia. Co-cultures were exposed to the neurosteroids allopregnanolone (THP) and tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC) (10 nM, a level found in brains in experimental ALF) (for review, see [25]), along with ammonia (5 mM) for 24 h, and BBB permeability was determined as described above. Both THP and THDOC significantly reduced the slight endothelial permeability observed following ammonia treatment (69.13 and 58.64%, respectively) (Figure 2). Similar BBB protection was observed when these neurosteroids were added in co-culture system along with LPS (55.67% with THP and 50.74% with THDOC) (Figure 2).

Effect of liver toxins on the BBB breakdown

As noted above, controversies exist surrounding the integrity of the BBB in animal models of ALF induced by the hepatotoxins galactosamine and azoxymethane, although there is no report of a BBB breakdown in the TAA-induced ALF in rats. This variable effect of hepatotoxins suggested the possibility that some hepatotoxins may additionally injure the BBB, independent of their effect on the liver. Accordingly, we examined whether galactosamine, azoxymethane, and thioacetamide (TAA) (commonly used to produce ALF) may have any direct toxic effect on the BBB in the astrocyte-endothelial co-culture system. Cells were treated with these agents (galactosamine, 25 μg/ml; azoxymethane, 5 μg/ml; TAA, 25 μg/ml; doses were selected based on the concentration used in animal models of ALF) and the status of the BBB integrity was determined using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran, as noted above. We found a slight increase in endothelial permeability to TAA and galactosamine (29.3 and 30.67%, respectively) (Figure 2). On the other hand, we found a major disruption of the BBB (218.4%) when cultures were exposed to the hepatotoxin azoxymethane (Figure 2), which was 1.4-fold greater in magnitude as compared to LPS, a classical inducer of BBB disruption. Additionally, exposure of co-cultures to THP and THDOC (10 nM), significantly diminished the effect of TAA on BBB permeability (by 43.01 and 56.31%, respectively). While THDOC significantly reduced the effect of galactosamine on BBB permeability (50.11%), THP showed a no significant reduction in BBB permeability. It should be emphasized that these neurosteroids failed to exhibit protection against the azoxymethane-induced BBB disruption (Figure 2). These studies indicate that the absence of a BBB breakdown in models of ALF (other than azoxymethane) is likely due to the protective effect of neurosteroids.

Discussion

This study demonstrates a slight endothelial permeability when co-cultures (astrocytic-endothelial) are treated with a pathophysiological concentration of ammonia or with the hepatotoxins thioacetamide (TAA) and galactosamine, and that neurosteroids (THP and THDOC) reduced such effect. On the other hand, the hepatotoxin azoxymethane caused a severe breakdown of the BBB in the co-culture system, while the neurosteroids THP and THDOC failed to show a significant protection against the azoxymethane-induced BBB disruption. These studies suggest that the BBB is intact in the TAA and galactosamine-induced animal models of ALF, and that the intactness appears to be the consequence of a protective effect exerted by neurosteroids which are synthesized in brain.

Swelling of astrocytes (cytotoxic brain edema) i.e., an intracellular accumulation of fluid due to the inability of brain cells to adequately regulate their intracellular volume, represents the major histopathological component of the edema in patients with ALF [9, 10]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data obtained from patients with ALF (by measuring apparent diffusion coefficient, which quantifies movement of water molecule across cell membrane) also indicates that the edema is cytotoxic [11, 32]. Recent diffusion-weighted imaging (diffusion tensor imaging, DTI) studies revealed a reduction in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in patients with ALF, indicating a reduction in the size of the extracellular space, consistent with an intracellular accumulation of water [11, 12]. These findings strongly support the view that the brain edema in humans with ALF is largely, if not exclusively, cytotoxic.

A recent study, however, suggested that in patients dying with ALF, the brain edema is vasogenic in origin since there was evidence of brain microvessel endothelial cell shrinkage, endothelial tight-junction abnormalities, and a reduction in occludin protein expression [20]. However, an actual breach in the BBB was not demonstrated in their human study; rather, the authors documented a profound degree of astrocyte swelling. While the reason for the endothelial changes described in their report is not clear, it is possible that complications associated with ALF that were present in their patients, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatitis, and urinary tract infections, may have contributed to the BBB breakdown [33]. Additionally, other complications that commonly occur in ALF, such as hypotension, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, and dehydration that were present in these patients may have also contributed to a disturbance of the BBB (for reviews, see [34, 35]). Such BBB changes, however, are not a direct consequence of ALF per se, but rather the results of complications associated with ALF.

Controversies also exist surrounding the integrity of the BBB in animal models of ALF. Traber et al.[36], 1987 reported that capillary endothelial cells are normal, and no evidence of brain extravasations to horseradish peroxidase was identified in rabbits with galactosamine-induced ALF, indicating the absence of BBB breakdown in this model of ALF. BBB breakdown was also not identified in hepatectomized rats [37]. Additionally, while a generalized breakdown of the BBB (as occurs in the vasogenic edema following ischemia and trauma) was not identified, selective abnormalities in blood–brain transport of amino acids have been described [38–41]. No change in BBB integrity was noted in the TAA rat model of ALF [42–44].

In contrast, BBB breakdown was reported in the galactosamine-induced animal model of ALF in rodents [45], as well as in the azoxymethane-induced ALF in mice [46]. BBB breakdown was also identified in hepatic devascularized pigs [47]. Furthermore, alterations in the expression of BBB tight junctional proteins, such as occludin, claudin-5, zonula occludens 1 and 2, have been demonstrated in an animal model of ALF [48]. As noted above, it is possible that secondary complications which very commonly occur in ALF, may have contributed to a disturbance of the BBB in these animals.

Cell culture studies also support the cytotoxic aspect of brain edema in ALF. Treatment of cultured astrocytes with a pathophysiologically relevant concentration of ammonia (5 mM) was shown to induce cell swelling [8, 16–19] (for review, see [8]). Exposure of rat cerebral cortical slices or organotypic slice cultures from mouse forebrain to 1–10 mM ammonia were also shown to induce astrocyte swelling [14, 15].

Ammonia plays a major role in the development of astrocyte swelling/brain edema in ALF. Studies in hyperammonemic primates [49], dogs [50], and rats [51, 52], as well as in vitro models of hyperammonemia [14, 16, 53] have all been shown to cause astrocyte swelling. Thus, there is compelling evidence for a major role of ammonia in the astrocyte swelling associated with ALF. While the mechanisms by which ammonia exerts its effect on astrocyte swelling are not fully understood, increased intracellular pH, calcium, oxidative stress, the mitochondrial permeability transition, mitogen-activated protein kinases, activation of the nuclear factor-kappaB, abnormalities in ion transporters and exchangers, as well as the water channel aquaporin-4, have all been strongly implicated in its pathogenesis ([54–57]; and for review, see [8]).

Our current study demonstrates a slight degree of endothelial permeability when co-cultures (astrocytic-endothelial) were treated with a pathophysiological concentration of ammonia or with the hepatotoxins TAA and galactosamine, and that neurosteroids (THP and THDOC) diminished this effect. These studies suggest that the BBB is intact in TAA or galactosamine-induced animal models of ALF, and that such effect appears to be the consequence of neurosteroids that are synthesized in brain in the setting of ALF (for review, see [8]). On the other hand, the hepatotoxin azoxymethane caused a severe breakdown of the BBB in the co-culture system and the neurosteroids THP and THDOC failed to show a significant protection against the BBB disruption. The finding that azoxymethane caused a severe breakdown of the BBB and failure of neurosteroids to protect such BBB breakdown question the suitability of azoxymethane-induced hepatotoxicity as an experimental model of ALF.

Experimental findings have consistently demonstrated the neuroprotective effect of neurosteroids in a variety of animal and human brain injury models [31]. Allopregnanolone, a metabolite of progesterone, was shown to reduce inflammation, BBB permeability, and edema after stroke [21–24] and traumatic brain injury [58–60]. While the means by which neurosteroids exert their protective effect on BBB breakdown induced by liver toxins (ammonia, TAA or galactosamine) are yet to be defined, it is possible that neurosteroids may prevent the production of inflammatory cytokines that are known to impair the BBB. In support of this mechanism, studies have shown the protective effect of allopregnanolone on the functional and structural integrity of the BBB following ischemia ([31] and references therein) as a consequence of its inhibition on the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6, as well as by inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 [31]. A recent report also described a slight increase in the paracellular permeability (27%) using cultured endothelial cell line (RBE-4) after exposure to ammonia and that such effect was mediated in part through increased matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 [30], suggesting that increased MMPs release by ammonia and their effect on BBB breakdown may have been rescued by neurosteriods in the TAA or galactosamine animal models of ALF.

Summary

While recent reports suggest the possibility of both cytotoxic and vasogenic components of brain edema in ALF, studies in humans and experimental models indicate that the edema in ALF is largely cytotoxic (due to astrocyte swelling). This study therefore examined whether liver toxins have a direct toxic effect on the BBB in a co-culture model of BBB. We found slight endothelial permeability when co-cultures were treated with a pathophysiological concentration of ammonia, and that neurosteroids (THP and THDOC) ameliorated such effect. Similar findings were observed when co-cultures were exposed to the hepatotoxins TAA and galactosamine. By contrast, the hepatotoxin azoxymethane caused a severe breakdown of the BBB in the co-culture system. Additionally, the neurosteroids THP and THDOC significantly diminished the effect of TAA and galactosamine on BBB permeability, whereas these neurosteroids failed to exhibit a significant protection against the azoxymethane-induced BBB disruption. These in vitro studies strongly suggest that the BBB is intact in the TAA or galactosamine-induced animal models of ALF, and that such effect appears to be a consequence of neurosteroids that are synthesized in brain in ALF. However, the possibility of a BBB breakdown can not be excluded when secondary complications occur in the setting of ALF (infections, hypotension, alcohol intoxication, hypoglycemia, hypoxia and dehydration). In aggregate, these in vitro findings strongly suggest that BBB disruption is not a feature of ALF per se, nor an aspect of the TAA or galactosamine animal models of ALF,

Highlights.

Studies have suggested the possibility of both cytotoxic and vasogenic edema in ALF

Ammonia had no effect on the permeability of the BBB in an in vitro model

TAA and galactosamine did not cause BBB breakdown in an in vitro model

Lipopolysaccharide and azoxymethane severely break the BBB in an in vitro model

Neurosteroids protect the BBB after TAA and galactosamine but not with azoxymethane

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Merit Review from the Department of Veterans Affairs and by a National Institutes of Health grant DK063311. The authors thank Alina Fernandez-Revuelta for the preparation of cell cultures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wakim-Fleming JÉ. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78:597–605. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WM. 2012;33:36–45. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1301733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shawcross DL, Wendon JA. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalan R, Olde Damink SWM, Hayes PC, Deutz NEP, Lee A. J Hepatol. 2004;41:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ede RJ, Williams R. 1986;6:107. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoofnagle JH, Carithers RL, Jr, Shapiro C, Ascher N. Hepatology. 1995;21:240–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernal W, Hall C, Karvellas CJ, Auzinger G, Sizer E, Wendon J. Hepatology. 2007;46:1844–1852. doi: 10.1002/hep.21838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norenberg MD, Rama Rao KV, Jayakumar AR. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:103–117. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez A. Acta Neuropathol. 1968;11:82–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00692797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato M, Hughes RD, Keays RT, Williams R. Hepatology. 2005;15:1060–1066. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rai V, Nath K, Saraswat VA, Purwar A, Rathore RKS, Gupta RK. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:334–341. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saksena S, Rai V, Saraswat VA, Rathore RS, Purwar A, Kumar M, Thomas MA, Gupta RK. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e111–e119. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayakumar AR, Norenberg M. Metab Brain Dis. 2013:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganz R, Swain M, Traber P, DalCanto M, Butterworth RF, Blei AT. Metab Brain Dis. 1989;4:213–223. doi: 10.1007/BF01000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Back A, Tupper KY, Bai T, Chiranand P, Goldenberg FD, Frank JI, Brorson JR. Neurol Res. 2011;33:1100–1108. doi: 10.1179/1743132811Y.0000000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norenberg MD, Baker L, Norenberg LOB, Blicharska J, Bruce-Gregorios J, Neary JT. Neurochem Res. 1991;16:833–836. doi: 10.1007/BF00965694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinehr R, Görg B, Becker S, Qvartskhava N, Bidmon HJ, Selbach O, Haas HL, Schliess F, Häussinger D. Glia. 2007;55:758–771. doi: 10.1002/glia.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson AK, Adermark L, Persson M, Westerlund A, Olsson T, Hansson E. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:556–565. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9819-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konopacka A, Konopacki FA, Albrecht J. J Neurochem. 2009;109:246–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lv S, Song HL, Zhou Y, Li LX, Cui W, Wang W, Liu P. Liver International. 2010;30:1198–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahesh VB, Brann DW, Hendry LB. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;56:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Betz A, Coester H. Acta neurochirurgicaSupplementum. 1990;51:256. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djebaili M, Guo Q, Pettus EH, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:106–118. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson CL, Coomber B, Rathbone J. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:324–332. doi: 10.1177/1073858409333069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahboucha S, Gamrani H, Baker G. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardoso FL, Kittel Á, Veszelka S, Palmela I, Tóth A, Brites D, Deli MA, Brito MA. PloS one. 2012;7:e35919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mans A, Saunders S, Kirsch R, Biebuyck J. J Neurochem. 1979;32:285–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swain M, Butterworth RF, Blei AT. Hepatology. 1992;15:449–453. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rama Rao KV, Reddy PV, Tong X, Norenberg MD. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1400–1408. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skowrońska M, Zielińska M, Wójcik Stanaszek L, Ruszkiewicz J, Milatovic D, Aschner M, Albrecht J. J Neurochem. 2012;121:125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishrat T, Sayeed I, Atif F, Hua F, Stein DG. Exp Neurol. 2010;226:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranjan P, Mishra AM, Kale R, Saraswat VA, Gupta RK. Metab Brain Dis. 2005;20:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s11011-005-7206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fletcher NF, Wilson GK, Murray J, Hu K, Lewis A, Reynolds GM, Stamataki Z, Meredith LW, Rowe IA, Luo G, Lopez-Ramirez MA, Baumert TF, Weksler B, Couraud PO, Kim KS, Romero IA, Jopling C, Morgello S, Balfe P. JA McKeating Gastroenterology. 2012;142:634–643. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sass DA, Shakil AO. Liver Transplantation. 2005;11:594–605. doi: 10.1002/lt.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dbouk N, McGuire BM. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:464–474. doi: 10.1007/s11938-006-0003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Traber PG, Canto MD, Ganger DR, Blei AT. Hepatology. 1987;7:1272–1277. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potvin M, Finlayson M, Hinchey E, Lough J, Goresky C. Lab Invest. 1984;50:560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horowitz M, Schafer D, Molnar P, Jones E, Blasberg R, Patlak C, Waggoner J, Fenstermacher J. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mans AM, Biebuyck JF, Hawkins RA. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol. 1983;245:C74–C77. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bassett M, Mullen K, Scholz B, Fenstermacher J, Jones E. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:747. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90298-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dixit V, Chang T. ASAIO Trans/Am Soc Art Intl Org. 1990;36:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albrecht J, Hilgier W, Januszewski S, Kapuściński A, Quack G. Neuroreport. 1994;5:671. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayakumar AR, Tong XY, Ospel J, Norenberg MD. Neuroscience. 2012;218:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin S, Wang XT, Liu L, Yao D, Liu C, Zhang M, Guo HF, Liu XD. Liver Int. 2012;33:274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cauli O, López–Larrubia P, Rodrigo R, Agusti A, Boix J, Nieto–Charques L, Cerdán S, Felipo V. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:638–645. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen JH, Yamamoto S, Steers J, Sevlever D, Lin W, Shimojima N, Castanedes-Casey M, Genco P, Golde T, Richelson E. J Hepatol. 2006;44:1105–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kristiansen RG, Lindal S, Myreng K, Revhaug A, Ytrebø LM, Rose CF. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:935–943. doi: 10.3109/00365521003675047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimojima N, Eckman CB, McKinney M, Sevlever D, Yamamoto S, Lin W, Dickson DW, Nguyen JH. J Invest Surg. 2008;21:101–108. doi: 10.1080/08941930802043565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voorhies TM, Ehrlich ME, Duffy TE, Petito CK, Plum F. Pediatr Res. 1983;17:970–975. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198312000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levin L, Koehler R, Brusilow S, Jones J, Traystman R. Intracranial Pressure. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 1032–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi H, Koehler RC, Brusilow SW, Traystman RJ. Am J Physiol-Heart Circul Physiol. 1991;261:H825–H829. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.3.H825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willard-Mack C, Koehler R, Hirata T, Cork L, Takahashi H, Traystman R, Brusilow S. Neuroscience. 1996;71:589–599. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zwingmann C, Flögel U, Pfeuffer J, Leibfritz D. Dev Neurosci. 2000;22:463–471. doi: 10.1159/000017476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jayakumar AR, Panickar KS, Murthy CR, Norenberg MD. J Neuroscience. 2006;26:4774–4784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0120-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jayakumar AR, Liu M, Moriyama M, Ramakrishnan R, Forbush B, III, Reddy PV, Norenberg MD. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33874–33882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jayakumar AR, Valdes V, Norenberg MD. J Hepatol. 2011;54:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jayakumar A, Bethea J, Tong X, Gomez J, Norenberg M. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Q, Sayeed I, Baronne LM, Hoffman SW, Guennoun R, Stein DG. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Connor CA, Cernak I, Vink R. Brain Res. 2005;1062:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright DW, Bauer ME, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:901–909. doi: 10.1089/089771501750451820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]