Abstract

Ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma (AFOS) is an extremely rare malignant odontogenic tumor. Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Deaths due to disease recurrence and/or progression are documented. Here, we report the case of a 15‐year‐old female with multiple recurrent AFOS. She responded to chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin consolidated by stereotactic reirradiation using cyberknife and remained in complete remission 14 months from the end of reirradiation therapy. Chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin should be considered in advanced cases of AFOS. Pediatr Blood Cancer © 2015 The Authors. Pediatric Blood & Cancer Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: ameloblastic fibro‐odontoma, ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma, chemotherapy response, radiotherapy, relapse, transformation

Abbreviations

- AFO

ameloblastic fibro‐odontoma

- AFS

ameloblastic fibrosarcoma

- AFOS

ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma

- CT

computerized tomography

- HE

hematoxylin‐eosin

- hpf

high‐power field

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Malignant odontogenic tumors are extremely rare entities, occurring as carcinomas or sarcomas. Odontogenic sarcomas are mixed tumors with two components: benign ameloblastic epithelium and malignant fibrous stroma, with or without dentine and enamel. The current 2005 WHO classification distinguishes two groups: ameloblastic fibrosarcoma [AFS (9330/3)] (malignant fibrous tissue with ameloblastic epithelium) and ameloblastic fibrodentino‐ and fibro‐odontosarcomas [AFOS (9290/3)] (with admixed dentine and enamel, respectively).1 Surgical excision is the accepted treatment. Chemotherapy responses have been reported for selected cases of AFS: one complete response was observed,2 and two cases of good response were consolidated by surgery and radiotherapy.3

AFOS is considered a low‐grade tumor, possibly less aggressive than AFS, with only one report of regional metastasis.1 However, recurrences and fatalities due to recurrence/progression involving the skull base have been reported.4, 5 No data on chemotherapy in AFOS exist.

CASE STUDY

An 8‐year‐old female was referred to a maxillofacial surgeon with a right‐sided facial mass involving the right maxillary antrum. Biopsy suggested a hamartomatous complex odontoma. Curettage and macroscopic tumor resection was performed with histology of the resection specimen identical to the previous biopsy. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged from follow‐up after 3 years.

Six years from initial presentation, the patient developed a painless swelling lateral to the right maxillary antrum. A computerized tomography (CT) scan showed a 3.7 × 3.4 cm soft tissue mass within the right maxilla with bony destruction of the lateral and posterior wall of the antrum. Debulking surgery with curettage was performed. Histopathology revealed an AFOS with marginal involvement. The patient was referred to our institution for further management.

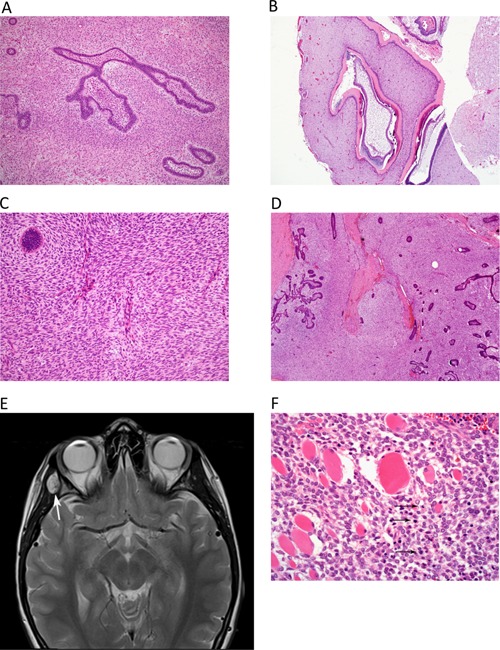

Histopathological review of the resection specimens demonstrated that the initial tumor was a benign ameloblastic fibro‐odontoma (AFO) (Fig. 1A and B). The specimen at recurrence showed evidence of malignant transformation to AFOS (Fig. 1C and D). The stromal component showed greater cellularity, with loose fascicles of mildly atypical spindle cells with a mitotic index of 5/10 high‐power fields (hpf). CT scans showed no evidence of residual local or pulmonary metastatic disease (pT3a, N0, M0, IRS II A, grade 2). The patient received radical intensity‐modulated radiotherapy to the right maxilla: 60 Gy in 30 fractions over 6 weeks.

Figure 1.

Histologic findings in the AFO and AFOS specimen and on MRI prior to first relapse. (A,B) Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) stained sections of the initial tumor [ameloblastic fibro‐odontoma (AFO)]. (A) Small islands and branching cords of ameloblastic epithelium are interspersed within spindle cell stroma. The mesenchymal component is of moderate cellularity, but no pleomorphism is present and mitotic activity is low (up to 2/10 hpf; magnification 100×. (B) Other areas show odontogenic epithelium and dentine; magnification 40×. (C,D) HE‐stained section of the first tumor recurrence [ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma (AFOS)]. (C) The prominence of the mesenchymal (spindle cell) component is apparent and is of higher cellularity than the initial AFO; magnification 40×. (D) The fascicular fibrosarcoma‐like architecture of the spindle cell component is discernible in areas, and only a small island of epithelium is seen here (top left). There is a focal mild atypia, and increased mitotic count of the mesenchymal component (5/10 hpf); magnification 100×. (E) Surveillance MRI 4 months after completion of radiotherapy for AFOS with involved margins. T2‐weighted sequence shows focal area of high signal (arrows) lying on lateral wall of right orbit, involving right temporalis muscle. (F) HE‐stained section of the first relapse of AFOS. The tumor shows more aggressive morphology, with prominent cellularity and pleomorphism of the mesenchymal component, along with numerous mitotic figures (arrows) and a significantly increased mitotic index of 17/10 hpf. The tumor is seen to extensively infiltrate skeletal muscle fibres. The epithelial component is markedly reduced and is not seen in this field; magnification 200×.

Four months after radiotherapy, surveillance magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 14 mm × 9 mm ovoid lesion consistent with a lymph node or possible tumor recurrence (Fig. 1E). An ultrasound at the same time demonstrated a well‐circumscribed hypoechoic soft tissue mass. There was interval growth on ultrasound scan 4 weeks later, when the patient presented with a further painless swelling in her right temporal region, superior to the previous tumor site and outside the radiation field. Biopsy confirmed relapse of AFOS and pre‐surgical CT demonstrated that the lesion was gradually enlarging but did not show overt evidence of bony erosion. Craniofacial resection of the mass was performed through combined bicoronal and intraoral access, the former to allow excision of the right temporalis muscle, and the latter to facilitate removal of the right coronoid process of the mandible. The tumor was adherent to the lateral skull base and as such, the lateral cortex of bone was removed at this site to further secure clearance.

Histopathology indicated an increasingly aggressive recurrent AFOS with increased cellularity, moderate pleomorphism, increased mitotic index, and extensive infiltrative behavior (Fig. 1F). Microscopic clearance was achieved at all but the medial margin at the sphenoid bone but in view of the further shaving of the bone, surgery was considered as complete.

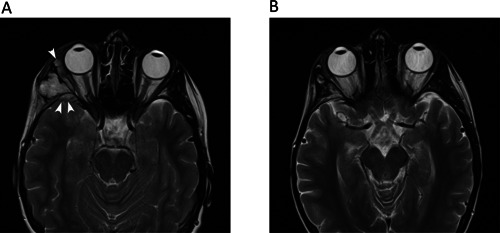

Three months after surgery, the patient developed diplopia and right periorbital swelling suspicious of second relapse of AFOS. MRI revealed a soft tissue mass arising from the right greater wing of sphenoid measuring 4.0 × 3.3 cm. There was bony erosion through the lateral wall of the right orbit with extension into the orbital fat and intracranially into the right temporal fossa (Fig. 2A). Chemotherapy with ifosfamide (3 g/m2 on days 1–3) and doxorubicin (37.5 mg on days 1 and 2) every 21 days was given for a total of six cycles without dose reductions or significant delay. There was an immediate clinical improvement in the swelling and normalization of the double vision after three chemotherapy cycles. MRI performed after every two cycles showed gradual partial response to treatment, most evident after six cycles (Fig. 2B). The patient required hospital admissions for antibiotic treatment of febrile neutropenia and pain management for mucositis. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor was given from cycle 4 onwards. Subsequent cyberknife‐based stereotactic ablative radiotherapy was given to the site of recurrence, including overlap with previous irradiation, delivering 42 Gy in three fractions to the 72% isodose for consolidation. The patient remained free of disease recurrence 14 months from completing cyberknife therapy, although she experienced recurrent infection in the area receiving Cyberknife reirradiation, probably related to radiation necrosis of bone.

Figure 2.

MRI findings prior to and after chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin. (A) MRI findings of second relapse of AFOS: T2‐weighted MRI demonstrates a lobulated mass returning high signal, at the site of resected tumor. Post‐surgical baseline imaging less than 3 months earlier had shown no lesion at this site. Note that soft tissue penetrates into the middle cranial fossa and orbit (arrowheads). (B) Response to six cycles of chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin on MRI: T2‐weighted MRI demonstrates resolution of the mass lesion (arrow). Some residual fatty change is present. Cyberknife radiotherapy was subsequently administered to the tumor bed.

DISCUSSION

AFOS is an extremely rare subtype of odontogenic sarcoma. Seventeen cases have been reported in the literature to date.1, 6, 7, 8, 9 In contrast, although still rare, 66 cases of AFS had been published in the literature in 2007 so that incidence, recurrence rate, and histologic behavior are better understood.6 With this report, we contribute to better understanding of the rare disease entity of AFOS and highlight the potential role of chemotherapy in its management.

The following three major points from this case may help guide clinicians in future similar cases:

Firstly, the AFOS in our patient developed on the background of an AFO, which had initially been thought to represent a hamartomatous complex odontoma. Our case highlights that recurrence of swelling close to the initial site of AFO must raise suspicion not only of recurrent AFO but also of malignant transformation to AFOS. Up to one‐third of AFS develop from ameloblastic fibroma,6, 10 and there are three case reports of AFO transforming to AFOS to date.6, 11 Our case supports this etiologic sequence, and highlights that the possibility of malignant recurrence must be considered in planning the follow‐up of these patients.

Secondly, AFS has been reported to become increasingly aggressive clinically with each recurrence. The recurrence rate overall is 37% and the disease is fatal in 20% due to locally progressive disease.10, 12 The histopathological presentation can change accordingly with each recurrence; AFS demonstrates increasing evidence of stromal cellularity and mitotic activity but diminishing evidence of odontogenic epithelium,6 and we here describe a similar observation in recurrent AFOS (Fig. 1).

Thirdly, and most importantly, the accepted treatment for AFOS is surgical resection. However, recurrences and fatal cases due to progression with involvement of the skull base have been reported in at least two cases.4, 5 Although chemotherapy has been used successfully in AFS.2, 3 there are no published data on chemotherapy in AFOS. Given the unfavorable situation for our patient, we opted to try chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin, a well‐established combination for non‐rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas in children.13 We demonstrate that the tumor was responsive to this chemotherapy regimen, suggesting that it would be appropriate to manage AFOS in children in the same way as other high‐grade non‐rhabodomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas using ifosfamide and doxorubicin treatment for unresectable tumors, after resection of grade 3 tumors >5 cm, or for tumors with locoregional spread (EpSSG NRSTS protocol, NCT00334854. The chemosensitivity noted here supports a possible role as neoadjuvant therapy to facilitate complete resection in cases where resection may be difficult either at initial diagnosis or in the event of recurrence.

In conclusion, AFOS is a rare tumor that may arise from AFO and can show increasing aggressive features at successive recurrences, and for which chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin may have a role in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting.

NOTE ADDED TO THE PROOF

Subsequent to the preparation of this report the patient developed progressive radiation necrosis of the right temporal lobe which was noted on surveillance imaging. This was successfully treated with 3 courses of 7.5 mg/kg bevacizumab at 21 day intervals with stabilisation of the edema and high T2 signal apparent on MRI.

The patient remains clinically asymptomatic and is in remission at the primary site 2 years from the cyberknife treatment. However, she has developed 3 small pulmonary nodules (maximum diameter 12 mm), presumed to be metastatic lesions from the AFOS, which have been treated with radiofrequency ablation. A tissue diagnosis was not obtained. The appearance of presumed pulmonary metastases may support the view that chemotherapy should be considered at an early stage of treatment in AFOS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the patient and her parents for giving us permission to publish her case. We further are grateful to all doctors and nurses involved in her care, especially Dr. Kimberley Allan who was a pathologist involved in the initial diagnosis of the AFOS and Dr. Frank Saran who carried out the first radiotherapy. We acknowledge support from the NIHR RM/ICR Biomedical Research Centre.

[The copyright line for this article was corrected in July 2015 after original online publication.]

Conflict of interest: Nothing to declare

REFERENCES

- 1. Carlos R, Alini M, Takeda Y. Odontogenic sarcomas In: Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. p. 294–295. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldstein G, Parker FP, Hugh GS. Ameloblastic sarcoma: Pathogenesis and treatment with chemotherapy. Cancer 1976; 37:1673–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Minard‐Colin V, Cassagneau E, Supiot S, Oberlin O, D'hautuille C, Corradini N. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma of the mandible: Report of 2 chemosensitive pediatric cases. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 34:e72–e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takeda Y, Kuroda M, Suzuki A. Ameloblastic odontosarcoma (ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma) in the mandible. Acta Pathol Jpn 1990; 40:832–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh I, Yadav SP, Kalra GS, Sen R, Gathwala L. Ameloblastic sarcoma with diverse mesenchymal differentiation. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 49:57–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jundt G, Reichart PA. Maligne odontogene tumoren. Pathologe 2008; 29:205–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mainenti P, Oliveira GS, Valério JB, Daroda LS, Daroda RF, Brandão G, Rosa LE. Ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma: A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 38:289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang S, Shi H, Wang P, Yu Q. Ameloblastic fibro‐odontosarcoma of the mandible: Imaging findings. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2011; 40:324–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reiser V, Alterman M, Shuster A, Kaplan I. Pediatric ameloblasticfibro‐odontosarcoma of the mandible: A challenge of diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 71:e45–e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bregni RC, Taylor AM, García AM. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma of the mandible: Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med 2001; 30:316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howell RM, Burkes EJ. Malignant transformation of ameloblastic fibro‐odontoma to ameloblastic fibrosarcoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1977; 43:391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kobayashi K, Murakami R, Fujii T, Hirano A. Malignant transformation of ameloblastic fibroma to ameloblastic fibrosarcoma: Case report and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2005; 33:352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferrari A, Casanova M. New concepts for the treatment of paediatric non‐rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma. Exp Rev Anticancer Ther 2005; 5:307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]