Summary

The dual SRC/ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor bosutinib is indicated for adults with Ph+ chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) resistant/intolerant to prior therapy. This analysis of an ongoing phase 1/2 study (NCT00261846) assessed effects of baseline patient characteristics on long‐term efficacy and safety of bosutinib 500 mg/day in adults with imatinib (IM)‐resistant (IM‐R; n = 196)/IM‐intolerant (IM‐I; n = 90) chronic phase (CP) CML. Median treatment duration was 24·8 months (median follow‐up, 43·6 months). Cumulative major cytogenetic response (MCyR) rate [95% confidence interval (CI)], was 59% (53–65%); Kaplan‐Meier (KM) probability of maintaining MCyR at 4 years was 75% (66–81%). Cumulative incidence of on‐treatment progression/death at 4 years was 19% (95% CI, 15–24%); KM 2‐year overall survival was 91% (87–94%). Significant baseline predictors of both MCyR and complete cytogenetic response (newly attained/maintained from baseline) at 3 and 6 months included prior IM cytogenetic response, baseline MCyR, prior interferon therapy and <6 months duration from diagnosis to IM treatment initiation and no interferon treatment before IM. The most common adverse event (AE) was diarrhoea (86%). Baseline bosutinib‐sensitive BCR‐ABL1 mutation was the only significant predictor of grade 3/4 diarrhoea; no significant predictors were identified for liver‐related AEs. Bosutinib demonstrates durable efficacy and manageable toxicity in IM‐R/IM‐I CP‐CML patients.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukaemia, chronic myeloid leukaemia, bosutinib, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, second‐line therapy

Bosutinib (SKI‐606) is an oral, dual SRC and ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved in the United States and Europe for the treatment of patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) resistant or intolerant to prior TKI therapy or for whom other TKIs are not appropriate choices (https://www.bosulif.com/; Isfort et al, 2014; Kantarjian et al, 2014).

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor selection is partly based on expected TKI tolerability and target specificity, as well as on existing BCR‐ABL1 mutations. In addition to inhibiting ABL1 tyrosine kinase, imatinib, nilotinib and dasatinib have specificity for KIT and platelet‐derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) (Bartolovic et al, 2004; Waller, 2010; Blay & von Mehren, 2011; Gnoni et al, 2011), inhibition of which has been linked to certain side effects (Leveen et al, 1994; Gambacorti‐Passerini et al, 2003; Tsao et al, 2003). In contrast, bosutinib has minimal specificity for KIT and PDGFR (Redaelli et al, 2010; Irvine & Williams, 2013), although it effectively inhibits SRC, a tyrosine kinase linked to CML progression that exhibits cross‐talk with BCR‐ABL1 signalling pathways (Li, 2008).

This follow‐up of an ongoing phase 1/2 study (Cortes et al, 2011) evaluated the effect of baseline patient characteristics on the long‐term efficacy and safety of second‐line bosutinib in imatinib‐resistant (IM‐R) or intolerant (IM‐I) chronic phase (CP) CML and assessed response durability and long‐term safety ≥48 months after the last patients’ first visit.

Methods

Patients

This analysis included adults (≥18 years) with Ph+ CP CML who had received prior imatinib treatment, frequently following other cytoreductive therapy [e.g, interferon (IFNα) or hydroxycarbamide]. Eligible patients were resistant to imatinib ≥600 mg/day or intolerant of any imatinib dose. Eligibility also required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of ≤1; adequate bone marrow (IM‐R only), hepatic and renal function; no prior antiproliferative treatment (except hydroxycarbamide and anagrelide) within 7 days and no allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation within 3 months of bosutinib initiation; a corrected QT interval of <470 ms at screening; and an absolute neutrophil count of >1000 × 109/l (IM‐R only). Patients with a documented history of BCR‐ABL1 T315I mutation could enter the study until an amendment (May 28, 2008) made such patients ineligible; patients already receiving treatment could continue the study if they were enrolled before the amendment or subsequently tested positive for the T315I mutation from a baseline sample. Additional inclusion/exclusion criteria were published previously (Cortes et al, 2011). Written informed consent was provided by all patients before study enrollment.

Study design

The study design was described previously (NCT00261846) (Cortes et al, 2011). In summary, part 1 dose‐escalation determined the recommended bosutinib starting dose (500 mg/day orally) used in part 2, which assessed the efficacy and safety of bosutinib in CP CML patients following 1 or more prior TKIs. Dose escalation to bosutinib 600 mg/day was permitted for lack of efficacy [no complete haematological response (CHR) by week 8 or no cytogenetic response by week 12] if no grade 3/4 drug‐related adverse events (AEs) had occurred. In parts 1 and 2, patients received treatment until progressive disease (PD), unacceptable toxicity or withdrawal of consent.

The protocol was approved by a central or institutional review board as required for each study site; the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Assessments

Cytogenetic response, assessed based on standard definitions (Cortes et al, 2011), was defined as newly achieved during the study or maintained from baseline for ≥4 weeks (earliest assessment time point); cumulative cytogenetic response data anytime on treatment are presented. All patients with a partial cytogenetic response (PCyR) at baseline were required to have ≥1 post‐baseline major cytogenetic response (MCyR) assessment to be counted as a responder and all patients with complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) at baseline were required to have ≥1 post‐baseline CCyR. Molecular responses were not assessed on the international scale and are therefore not included. Evaluable patients received ≥1 bosutinib dose and had a valid baseline assessment for the respective endpoint. Duration of response (DOR) was evaluated among responders from the first response date until confirmed loss of response, treatment discontinuation due to PD/death, or death within 30 days of last dose; patients without events were censored at their last assessment visit. Assessment of PD was based on previously described criteria (Cortes et al, 2011), including transformation to accelerated phase (AP) or blast phase (BP) CML, increasing white blood cell count (doubling over ≥1 month with second count >20 × 109/L and confirmed ≥1 week later), or loss of confirmed CHR or unconfirmed MCyR. Time from first dose to PD/death and time from first dose to transformation were evaluated through 30 days after the last dose; patients without events were censored at their last assessment visit. Overall survival (OS) was evaluated only up to 2 years after treatment discontinuation; patients still alive were censored at the last known alive date.

The safety population included patients who received ≥1 bosutinib dose. AEs were reported at each visit up to 30 days after the last dose and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3·0 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf). Physical examinations, vital sign recordings, electrocardiograms and laboratory tests were performed; abnormalities were reported as AEs if considered clinically significant by the investigator. Treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs) were defined as any new event starting during bosutinib therapy or within 30 days of the last dose or any event increasing in severity from baseline during that time period; newly occurring TEAEs were defined as those Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Preferred Terms (Brown, 2007) not experienced by the same patient previously for patients on treatment during a given year. TEAEs were analysed overall and by year of first occurrence. The duration from first dose to first grade 3/4 diarrhoea or liver‐related AEs was evaluated up to 30 days after the last dose; patients without events were censored at their last dose. Multiple gated acquisition scan analyses also were performed.

Statistical methods

Efficacy was summarized using response rates, confidence intervals (CIs) and descriptive statistics. Time‐to‐event distributions were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method (DOR, OS) or cumulative incidence adjusting for the competing risk of treatment discontinuation without the event (PD/death, transformation). The 2‐sided 95% CIs for response rates are based on the exact binomial. The 2‐sided 95% CIs for the Kaplan–Meier quartiles are based on the Brookmeyer‐Crowley linear transformation method. The Kaplan–Meier yearly rates with the associated 2‐sided 95% CI are based on Greenwood's formula. The cumulative incidence yearly rates with the associated 2‐sided 95% CI are based on Gray's method.

This retrospective, exploratory analysis evaluated demographic and baseline patient characteristics as predictors of (1) MCyR or CCyR by 3 months (first response up to but not including week 13) or 6 months (first response up to but not including week 25) or cumulative MCyR or CCyR using multivariable logistic regression, (2) progression‐free survival (PFS; time to PD/death unadjusted for competing risks) distribution using a multivariable Cox proportional cause‐specific hazard model, (3) OS distribution using a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model (OS distribution truncated at 2 years per protocol) and (4) time to first grade 3/4 diarrhoea or liver‐related AEs (any grade and grade 3/4) using a multivariable Cox proportional cause‐specific hazard model. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% CIs; P values were not adjusted for multiple testing. Cytogenetic response was assessed by baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutation status (results subject to change because mutational assessments are ongoing). A separate retrospective analysis was performed to evaluate age (<65 vs. ≥65 years) effects on response, long‐term outcomes and tolerability. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9·1·3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

A total of 286 patients with CP CML (IM‐R, n = 196; IM‐I, n = 90) were enrolled and treated (Table SI). The time from the last enrolled patient's first bosutinib dose to the data cut‐off was 51 months (204 weeks). At the time of the data snapshot (15 May 2013) based on an unlocked trial database for this interim publication, 113 (40%) patients [IM‐R, n = 79 (40%); IM‐I, n = 34 (38%)] were still receiving bosutinib. The median (range) follow‐up duration was 43·6 (0·6–83·4) months (overall); median (range) treatment duration was 24·8 (0·2–83·4) months (Table SII). Dose interruptions due to AEs occurred in 205 (72%) patients [IM‐R, n = 130 (66%); IM‐I, n = 75 (83%)] and dose reductions due to AEs occurred in 139 (49%) patients [IM‐R, n = 87 (44%); IM‐I, n = 52 (58%)]. Dose escalations to 600 mg/day occurred in 36 (13%) patients who started at <600 mg [IM‐R, n = 33 (18%); IM‐I, n = 3 (3%)]. Overall, 173 (60%) patients discontinued treatment [IM‐R, n = 117 (60%); IM‐I, n = 56 (62%)]; reasons for treatment discontinuation are listed in Table SII.

Older patients (≥65 years) were more frequently intolerant to prior imatinib (43% vs. 28%); more often had worse performance (ECOG PS score 0, 62% vs. 81%); had longer median (range) CML duration since diagnosis [5·4 (0·1–13·7) vs. 3·3 (0·2–15·1) years); and more frequently had baseline medical events, including hypertension (43% vs. 18%), anaemia (30% vs. 18%) and fatigue (21% vs. 14%; Table 1). Older patients had a shorter median (range) duration of treatment [13·9 (0·3–71·9) vs. 28·4 (0·2–83·4) months] and follow‐up [35·1 (0·9–74·0) vs. 46·8 (0·6–83·4) months] and a higher incidence of discontinuations (32% vs. 20%), dose reductions (57% vs. 46%) and dose interruptions (79% vs. 70%) due to AEs vs. younger patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes for younger (<65 years) vs. older (≥65 years) patients

| Parameter | <65 years (n = 223) | ≥65 years (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|

| Median (range) age, years | 48 (18–64) | 70 (65–91) |

| Male, n (%) | 117 (53) | 33 (52) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 132 (59) | 54 (86) |

| Asian | 58 (26) | 6 (10) |

| Black | 15 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Othera | 18 (8) | 2 (3) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 180 (81) | 39 (62) |

| 1 | 41 (18) | 24 (38) |

| 2 | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Median (range) number of ongoing medications at baseline | 2 (1–10) | 4 (1–12) |

| Prior IFNα therapy, n (%) | 71 (32) | 29 (46) |

| Prior imatinib therapy, n (%) | ||

| Intolerant | 63 (28) | 27 (43) |

| Resistant | 160 (72) | 36 (57) |

| Median (range) duration of CML diagnosis, years | 3·3 (0·2–15·1) | 5·4 (0·1–13·7) |

| Median (range) duration of bosutinib treatment, months | 28·4 (0·2–83·4) | 13·9 (0·3–71·9) |

| Median (range) follow‐up, months | 46·8 (0·6–83·4) | 35·1 (0·9–74·0) |

| Baseline medical history events, n (%) | 188 (84) | 61 (97) |

| Events occurring in ≥15% of patients (either age group), n (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 39 (18) | 27 (43) |

| Anaemia | 40 (18) | 19 (30) |

| Obesity | 41 (18) | 12 (19) |

| Fatigue | 31 (14) | 13 (21) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 35 (16) | 9 (14) |

| Depression | 15 (7) | 12 (19) |

| Periorbital oedema | 10 (5) | 10 (16) |

| Cytogenetic response,b n (%) [95% CI] | ||

| Evaluable patients | 203 | 61 |

| MCyR | 123 (61) [54–67] | 33 (54) [41–67] |

| CCyR | 101 (50) [43–57] | 29 (48) [35–61] |

| Probability of maintaining MCyR at 4 years, % (95% CI)c | 75 (66–82) | 72 (52–85) |

| TEAEs (any grade) with ≥8% difference between age groups, n (%) | ||

| Diarrhoea | 187 (84) | 58 (92) |

| Vomiting | 78 (35) | 29 (46) |

| Fatigue | 50 (22) | 24 (38) |

| Decreased appetite | 24 (11) | 17 (27) |

| Weight decreased | 18 (8) | 16 (25) |

| Asthenia | 26 (12) | 15 (24) |

| Dyspnea | 18 (8) | 15 (24) |

| Pleural effusion | 9 (4) | 14 (22) |

| Peripheral oedema | 17 (8) | 14 (22) |

| Back pain | 26 (12) | 13 (21) |

| Abdominal pain | 63 (28) | 12 (19) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 11 (5) | 11 (18) |

| ALT increased | 55 (25) | 9 (14) |

| AST increased | 47 (21) | 8 (13) |

| Chills | 10 (5) | 8 (13) |

| Neutropenia | 40 (18) | 6 (10) |

| Contusion | 2 (1) | 6 (10) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 29 (13) | 3 (5) |

| Dose interruption due to a TEAE, n (%) | 155 (70) | 50 (79) |

| Dose reduction due to a TEAE, n (%) | 103 (46) | 36 (57) |

| Discontinuation due to an AE, n (%) | 44 (20) | 20 (32) |

| Death within 30 days of last dose due to an AE, n (%) | 6 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Transformation to AP/BP CML at 4 years,d n (%) | 9 (4) | 2 (3) |

| PD/death at 4 years,e% [95% CI] | 18 (14–24) | 21 (13–34) |

| OS at 2 years,c , f% [95% CI] | 93 (88–95) | 87 (75–93) |

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, accelerated phase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BP, blast phase; CCyR, complete cytogenetic response; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; MCyR, major cytogenetic response; IFNα, interferon‐α; OS, overall survival; PCyR, partial cytogenetic response; PD, progressive disease; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome–positive; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Other races: American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 1), Hispanic (n = 15), Mestizo (n = 2), mixed race (n = 1), North African (n = 1).

Evaluable patients must have had an adequate baseline cytogenetic assessment with ≥20 metaphases or ≥1 Ph+ metaphase from bone marrow cytogenetics. Cytogenetic response (Baccarani et al, 2006) was determined using standard cytogenetics (G‐band karyotype) with ≥20 metaphases counted for postbaseline assessments; if <20 metaphases were available postbaseline, FISH analysis of bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood with ≥200 cells for the presence of BCR‐ABL1 fusion gene was used. MCyR included PCyR (1%–35% Ph+ metaphases) and CCyR (0% Ph+ metaphases; <1% if using FISH). Cytogenetic response could be newly achieved during the study or maintained from baseline for ≥4 weeks.

Based on Kaplan–Meier estimates.

Based on cumulative incidence adjusting for competing risk of treatment discontinuation without transformation.

Based on cumulative incidence adjusting for competing risk of treatment discontinuation without PD or death; PD defined as transformation to AP or BP CML, increasing white blood cell count (doubling over ≥1 month with second count >20 × 109/L and confirmed ≥1 week later), or loss of confirmed complete haematologic response or unconfirmed MCyR.

Patients were only followed for OS for 2 years after treatment discontinuation (per protocol).

Efficacy

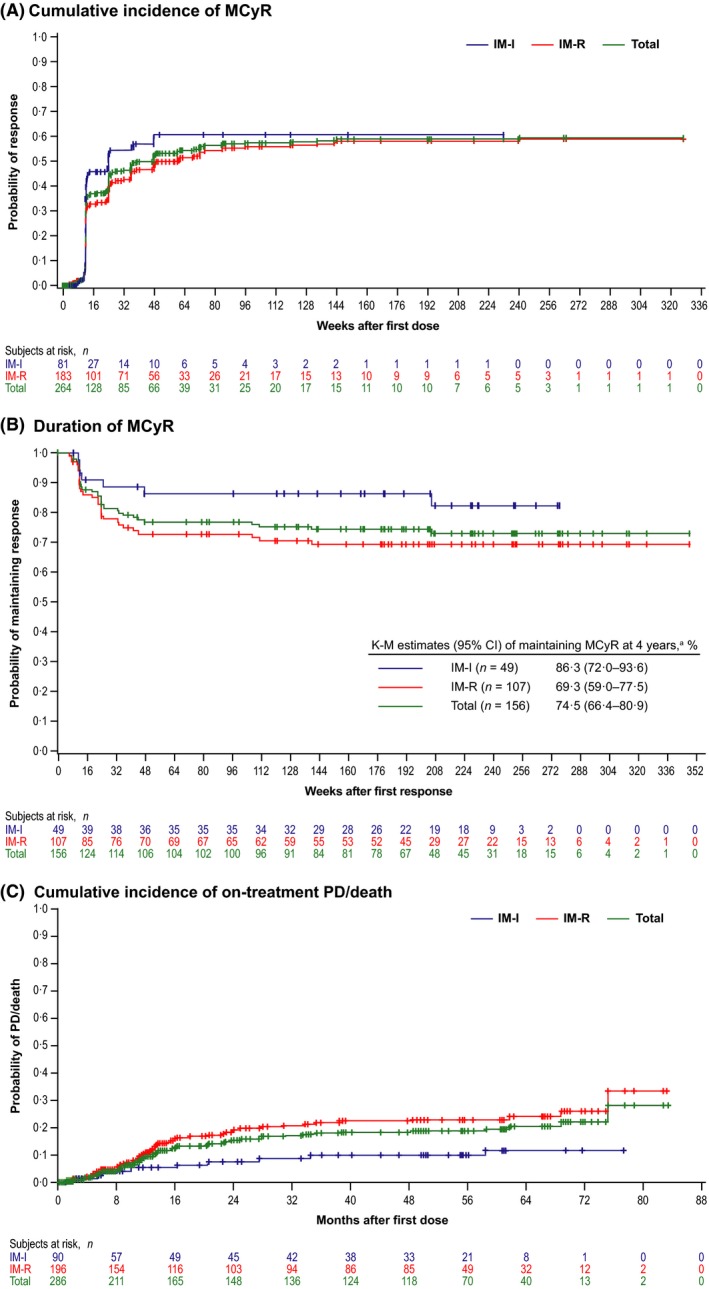

Among evaluable patients (n = 264), 156 [59% (95% CI, 53–65%)] newly attained or maintained a baseline MCyR for ≥4 weeks [IM‐R, 59% (n = 107/183); IM‐I, 61% (n =49/81), cumulative data]. CCyR was attained/maintained by 130 [49% (95% CI, 43–55%)] patients overall (IM‐R, 48%; IM‐I, 52%). Among 248 patients without a CCyR at baseline, 141 [57% (95% CI, 50–63%)] achieved an MCyR and 116 [47% (40–53%)] achieved a CCyR with bosutinib [IM‐R, 58% and 47%, respectively (n = 179); IM‐I, 55% and 46% (n = 69), respectively]. Of 16 patients (IM‐R, n = 4; IM‐I, n = 12) who had a CCyR at baseline, 14 (IM‐R, n = 4; IM‐I, n = 10) maintained CCyR for a duration ranging from approximately 12 to 288 + weeks postbaseline and 2 had no postbaseline assessment (both discontinued due to AEs prior to week 12); one IM‐I patient with PCyR at baseline maintained PCyR for approximately 36 weeks post‐baseline. MCyR and CCyR rates were generally similar by age (Table 1). The median time to MCyR among responders (n = 156) was 12·3 (95% CI, 12·1–12·7) weeks [IM‐R (n = 107), 12·3 (12·1–24·0) weeks; IM‐I (n = 49), 12·1 (12·0–12·3) weeks]; median time to CCyR among responders (n = 130) was 24·0 (95% CI, 12·3–24·1) weeks [IM‐R (n = 88), 24·1 (12·7–35·9) weeks; IM‐I (n = 42), 12·6 (12·1–24·0) weeks]. Cumulative incidences of MCyR and CCyR are shown in Fig 1A and Fig S1A, respectively. Kaplan‐Meier‐estimated probabilities of maintaining an MCyR or CCyR at 4 years remained high in the IM‐R and IM‐I groups (Fig 1B and Fig S1B); at the time of this report, the median duration of MCyR and CCyR had not yet been reached.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of (A) MCyR in all evaluable patients (responders and nonresponders) over time adjusting for the competing risk of treatment discontinuation without the event, (B) duration of MCyR among responders and (C) cumulative incidence of on‐treatment progressionb or death adjusting for the competing risk of treatment discontinuation without PD/death. CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; IM‐I, imatinib intolerant; IM‐R, imatinib‐resistant; K–M, Kaplan–Meier; MCyR, major cytogenetic response; PD, progressive disease. a20% of responders discontinued treatment with no loss of response, PD, or death. bCriteria for progression included transformation to accelerated phase/blast phase CML, increasing white blood cell count (doubling over ≥1 month with second count >20 × 109/L and confirmed ≥1 week later), or loss of confirmed complete haematologic response or unconfirmed MCyR.

Of 130 patients who reduced their dose to 400 mg/day due to an AE, 56 (43%) first achieved MCyR after dose reduction, whereas 18 (14%) achieved MCyR before dose reduction and maintained MCyR afterwards; only 3 (2%) patients lost MCyR after dose reduction. Of 49 patients who reduced their dose to 300 mg/day (including patients who first reduced dose to 400 mg/day), 8 (16%) first achieved a MCyR after dose reduction, 17 (35%) maintained MCyR after reduction and 2 (4%) lost MCyR after dose reduction (Table SIII).

Among 210 patients with known baseline mutational status, 79 (38%) had ≥1 of 42 unique BCR‐ABL1 kinase domain mutations, most commonly T315I (n = 9), M351T (n = 9), F359V (n = 9), G250E (n = 6), M244V (n = 6) and L248V (n = 5). Most of these patients (68/79) had only 1 baseline mutation. MCyR was observed across a spectrum of baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutations (62% vs. 59% for those with vs. without a baseline mutation [excluding T315I]; Fig S2).

Long‐term outcomes

The cumulative incidence of on‐treatment AP/BP transformation at 4 years was 4% (95% CI, 2–7%) overall [IM‐R, n = 9, 5% (2–9%); IM‐I, n = 2, 2% (<1–9%)]; 57% discontinued treatment without transformation. No new on‐treatment transformations occurred after 2 years.

At 4 years, the cumulative incidence of on‐treatment progression (including AP/BP transformation)/death was 19% (95% CI, 15–24%) overall [IM‐R, 22% (17–29%); IM‐I, 10% (5–19%); Fig 1C]; 40% (IM‐R, 35%; IM‐I, 51%) discontinued without on‐treatment progression/death. Kaplan–Meier–estimated 2‐year OS was 88% (95% CI, 83–92%) and 98% (91–99%) in IM‐R and IM‐I patients, respectively; per protocol, patients were followed for OS only for 2 years after the last dose. Forty (14%) deaths occurred on study: 32 within 1 year (7 within 30 days), 6 within 2 years and 2 within 3 years of the last dose. Most deaths were due to PD [n = 24 (8%); IM‐R, n = 22; IM‐I, n = 2] or AEs unrelated to treatment [n = 13 (5%); IM‐R, n = 11; IM‐I, n = 2]. No deaths were reported as treatment‐related. Three deaths due to unknown causes occurred ≥99 days after the last dose.

Among older vs. younger patients, the cumulative incidence of on‐treatment AP/BP transformation at 4 years was 3% (95% CI, 1–12%; n = 2) vs. 4% (2–8%; n = 9), respectively; the cumulative incidence of PD/death at 4 years [21% (13–34%) vs. 18% (14–24%)] and Kaplan–Meier–estimated OS at 2 years [87% (75–93%) vs. 93% (88–95%)] were numerically similar (Table 1).

Third/fourth‐line TKIs received by patients after discontinuing second‐line bosutinib (captured for up to 2 years after the last bosutinib dose) were most commonly dasatinib [18% (n = 51)], followed by nilotinib [13% (n = 37)] or nilotinib hydrochloride [2% (n = 7)], imatinib [6% (n = 16)] or imatinib mesylate [1% (n = 2)] and ponatinib [3% (n = 8)].

Baseline predictors of response and survival

The following baseline factors were associated with a significantly increased probability of attaining/maintaining an MCyR or CCyR (Table 2): younger vs. older age [MCyR by 3 months; (P = 0·0107)], men vs. women [MCyR anytime on treatment (P = 0·0438), CCyR by 3 or 6 months (P ≤ 0·0195)], prior imatinib response (at least a minimal cytogenetic response) vs. no response and prior IFNα treatment vs no prior treatment [MCyR and CCyR by 3 or 6 months, and anytime on treatment (P < 0·032)], Ph+ ratio ≤35% vs. >95% [MCyR and CCyR by 3 or 6 months, and anytime on treatment (P ≤ 0·0007)], Ph+ ratio ≤35% vs. >35–95% [MCyR by 3 months (P = 0·0383) and CCyR by 3 or 6 months, and anytime on treatment (P ≤ 0·0133)] and duration of <6 months (with no prior IFNα) vs. ≥6 months from diagnosis to IM initiation or IFNα treatment anytime before IM [MCyR or CCyR by 3 or 6 months (P ≤ 0·0032)]. The only significant predictor of decreased OS was baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutation status [bosutinib‐insensitive mutations vs no mutations: HR, 3·35 (95% CI, 1·11–10·14); P = 0·0325]; the effect of baseline Ph+ status on OS was not estimable (no deaths occurred in the Ph+ ratio ≤35% group). Baseline Ph+ ratio (≥95% vs. ≤35%) was significantly associated with decreased PFS [7·94 (95% CI, 1·79–35·16); P = 0·0063].

Table 2.

Baseline predictors of cytogenetic response

| Baseline Characteristic | OR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Months | 6 Months | Cumulative | |

| Age ≥65 years (n = 61) vs. <65 years (n = 202) | |||

| MCyR |

0·35 (0·16–0·79) P = 0·0107 |

0·80 (0·38–1·68) NS |

0·62 (0·31–1·25) NS |

| CCyR |

0·50 (0·20–1·23) NS |

0·57 (0·24–1·34) NS |

0·69 (0·34–1·41) NS |

| Women (n = 122) vs. men (n = 141) | |||

| MCyR |

0·79 (0·42–1·49) NS |

0·58 (0·31–1·07) NS |

0·55 (0·30–0·98) P = 0·0438 |

| CCyR |

0·39 (0·18–0·86) P = 0·0195 |

0·33 (0·16–0·71) P = 0·0046 |

0·61 (0·33–1·10) NS |

| Prior IM response: yes (n = 140) vs. no (n = 84)b | |||

| MCyR |

4·88 (2·06–11·60) P = 0·0003 |

2·84 (1·37–5·91) P = 0·0052 |

2·36 (1·21–4·61) P = 0·0119 |

| CCyR |

9·26 (1·88–45·70) P = 0·0063 |

20·84 (4·46–97·32) P = 0·0001 |

3·49 (1·72–7·05) P = 0·0005 |

| Prior IM response: unknown (n = 39) vs. no (n = 84)b | |||

| MCyR |

4·79 (1·55–14·75) P = 0·0064 |

1·94 (0·71–5·28) NS |

1·74 (0·70–4·33) NS |

| CCyR |

16·71 (2·73–102·36) P = 0·0023 |

20·28 (3·53–116·45) P = 0·0007 |

3·43 (1·32–8·92) P = 0·0117 |

| % Ph+ cells: <95% to >35% (n = 65) vs. ≤35% (n = 45)c | |||

| MCyR |

0·38 (0·16–0·95) P = 0·0383 |

0·43 (0·16–1·13) NS |

0·55 (0·19–1·59) NS |

| CCyR |

0·20 (0·08–0·52) P = 0·0009 |

0·19 (0·07–0·53) P = 0·0015 |

0·27 (0·10–0·76) P = 0·0133 |

| % Ph+ cells: ≥95% (n = 124) vs. ≤35% (n = 45)c | |||

| MCyR |

0·20 (0·08–0·51) P = 0·0007 |

0·15 (0·06–0·40) P = 0·0001 |

0·16 (0·06–0·45) P = 0·0005 |

| CCyR |

0·05 (0·02–0·16) P ≤ 0·0001 |

0·06 (0·02–0·18) P ≤ 0·0001 |

0·10 (0·03–0·27) P ≤ 0·0001 |

| % Ph+ cells: Unknown (n = 29) vs. ≤35% (n = 45)c | |||

| MCyR |

0·16 (0·04–0·65) P = 0·0107 |

0·12 (0·03–0·46) P = 0·0019 |

0·20 (0·06–0·71) P = 0·0124 |

| CCyR |

0·04 (0·004–0·37) P = 0·0046 |

0·08 (0·02–0·41) P = 0·0026 |

0·17 (0·05–0·60) P = 0·0062 |

| Prior IM resistance: yes (n = 182) vs. no (n = 81) | |||

| MCyR |

0·76 (0·37–1·60) NS |

0·73 (0·35–1·51) NS |

1·12 (0·55–2·29) NS |

| CCyR |

0·10 (0·41–2·44) NS |

0·79 (0·33–1·88) NS |

1·29 (0·63–2·66) NS |

| IFNα treatment before IM or diagnosis to IM initiation ≥6 months [n = 134] vs. <6 months [n = 129] | |||

| MCyR |

0·11 (0·03–0·41) P = 0·0009 |

0·16 (0·05–0·51) P = 0·0018 |

0·47 (0·19–1·16) NS |

| CCyR |

0·08 (0·02–0·43) P = 0·0032 |

0·09 (0·02–0·39) P = 0·0015 |

0·46 (0·18–1·19) NS |

| Prior IFNα: yes (n = 89) vs. no (n = 174) | |||

| MCyR |

5·66 (1·78–17·93) P = 0·0032 |

5·58 (1·97–15·81) P = 0·0012 |

3·66 (1·55–8·66) P = 0·0031 |

| CCyR |

5·26 (1·15–23·94) P = 0·0319 |

7·85 (2·00–30·84) P = 0·0032 |

3·32 (1·35–8·21) P = 0·0092 |

| BCR‐ABL1 mutation status: sensitive mutation (n = 26) vs. no mutation (n = 119)d | |||

| MCyR |

1·56 (0·51–4·75) NS |

1·46 (0·51–4·20) NS |

1·07 (0·37–3·08) NS |

| CCyR |

1·05 (0·26–4·16) NS |

2·95 (0·85–10·26) NS |

0·74 (0·26–2·11) NS |

| BCR‐ABL1 mutation status: insensitive mutation (n = 28) vs. no mutation (n = 119)d | |||

| MCyR |

0·79 (0·24–2·56) NS |

0·80 (0·27–2·40) NS |

0·66 (0·25–1·76) NS |

| CCyR |

1·40 (0·35–5·72) NS |

1·35 (0·36–5·11) NS |

0·78 (0·29–2·11) NS |

| BCR‐ABL1 mutation status: unknown sensitivity mutation (n = 23) vs. no mutation (n = 119)d | |||

| MCyR |

1·79 (0·55–5·81) NS |

1·47 (0·46–4·71) NS |

0·69 (0·23–2·09) NS |

| CCyR |

2·05 (0·53–8·00) NS |

2·41 (0·62–9·43) NS |

0·69 (0·22–2·14) NS |

| BCR‐ABL1 mutation status: unknown/missing mutation (n = 67) vs. no mutation (n = 119)d | |||

| MCyR |

0·73 (0·34–1·57) NS |

0·89 (0·42–1·87) NS |

0·63 (0·31–1·29) NS |

| CCyR |

0·50 (0·19–1·31) NS |

1·13 (0·47–2·76) NS |

0·59 (0·28–1·23) NS |

| Disease duration, years | |||

| MCyR |

1·05 (0·92–1·20) NS |

1·03 (0·90–1·16) NS |

0·98 (0·88–1·10) NS |

| CCyR |

1·04 (0·88–1·23) NS |

1·01 (0·86–1·19) NS |

0·98 (0·87–1·11) NS |

| Basophils, % | |||

| MCyR |

0·95 (0·86–1·06) NS |

0·95 (0·87–1·04) NS |

1·03 (0·95–1·12) NS |

| CCyR |

1·06 (0·94–1·19) NS |

1·02 (0·91–1·14) NS |

1·03 (0·95–1·12) NS |

CCyR, complete cytogenetic response; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; CP, chronic phase; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IM, imatinib; MCyR, major cytogenetic response; NS, not significant (P > 0·05); IFNα, interferon‐α; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome–positive; OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Note: 1 patient with a missing value for a baseline covariate was not included in any of the predictors analyses.

Odds ratios >1 and hazard ratios <1 indicate better outcome for group 1 vs. group 2. P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Prior response was defined as achievement of at least a minimal cytogenetic response (standard cytogenetic criteria: 66% to 95% Ph+ cells from bone marrow or BCR‐ABL1 from FISH).

Required ≥20 metaphases for standard cytogenetics or ≥200 cells for FISH.

Bosutinib‐sensitive mutations are those resulting in half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) ≤2‐fold higher than wild type (M244V, Q252H, Y253H/F, D276G, E279K, E292L, M343T, M351T, F359V, L384M, H396P/R and G398R) and bosutinib‐insensitive mutations are those resulting in IC50 values >2‐fold higher than wild type (L248R/V, G250E, E255K/V, V299L, T315A/I/V, F317L/R/V, F359I and F486S); the sensitivities of all other mutations are unknown. If patients had >1 mutation with different sensitivities, they were categorized based on the following hierarchy: bosutinib‐insensitive, unknown sensitivity and bosutinib‐sensitive (Redaelli et al, 2009, 2012).

Safety and tolerability

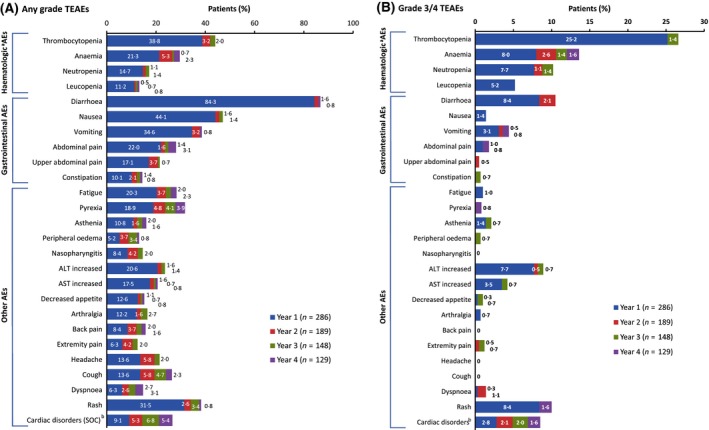

The incidence of haematologic and non‐haematologic TEAEs in ≥10% of patients and maximum on‐treatment grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities in ≥5% of patients were reported previously for this cohort (Kantarjian et al, 2014). The overall incidence of newly occurring TEAEs generally decreased over time [any TEAE: year 1, 99·7% (n = 285/286); year 2, 73% (n = 138/189); year 3, 66% (n = 97/148); and year 4, 49% (n = 63/129)] as well as in the IM‐R and IM‐I subpopulations. Individual TEAEs (occurring in ≥10% of patients overall) generally were most frequent in year 1 (Fig 2). Notably, increased blood creatinine (any grade), which occurred in 22/286 (8%) patients overall, had a higher incidence in years 3 [7/148 (5%)] and 4 [6/129 (5%)] vs. years 1 [7/286 (2%)] and 2 [2/189 (1%)]. TEAEs that occurred with a difference of ≥8% between age groups (<65 vs. ≥65 years) are shown in Table 1; the most common TEAEs (>15% difference between these age groups) included fatigue (22% vs. 38%, respectively), decreased appetite (11% vs. 27%), weight decrease (8% vs. 25%), dyspnea (8% vs. 24%) and pleural effusion (4% vs. 22%).

Figure 2.

Incidence of TEAEs of (A) any grade and (B) grade 3/4 occurring in year 1 and newly occurring in years 2, 3 and 4 in ≥10% of patients overall (any grade). AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SOC, system organ class; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event. Denominators are the number of patients on treatment during the specific years. Newly occurring TEAEs were defined as those Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Preferred Terms not experienced by the same patient previously for patients on treatment during a given year. aHaematological AEs were clustered with related terms from investigations: thrombocytopenia also includes platelet count decreased; anaemia also includes haemoglobin decreased; neutropenia also includes neutrophil count decreased and leukopenia also includes white blood cell count decreased. bCardiac Disorders (SOC) includes all preferred terms; one additional patient had a cardiac AE in year 1 (electrocardiogram QT prolonged) that did not have another TEAE from the SOC of Cardiac Disorders.

AEs led to treatment discontinuation in 32 (16%) IM‐R patients and 35 (39%) IM‐I patients; most discontinuations due to AEs occurred during the first treatment year (Table SIV). The median (range) time to discontinuation was 162 (7–2288) days in IM‐R patients and 115 (14–1625) days in IM‐I patients. Common reasons for discontinuation among patients with dose reductions to 400 mg/day (n = 130) or 300 mg/day (n = 49) included AEs [30% (IM‐R, n = 18; IM‐I, n = 21) and 31% (IM‐R, n = 6; IM‐I, n = 9), respectively], disease progression [12% (IM‐R, n = 11; IM‐I, n = 4) and 12% (IM‐R, n = 4; IM‐I, n = 2)] and unsatisfactory response [6% (IM‐R, n = 6; IM‐I, n = 2) and 10% (IM‐R, n = 4; IM‐I, n = 1)]. The most common AEs leading to dose reduction were thrombocytopenia [16% (n = 45)], rash [7% (n = 21)] and diarrhoea [5% (n = 14)]. Among the 67 patients overall who discontinued due to an AE, 28 (42%) discontinued without attempting dose reduction to <500 mg/day for that event.

Although diarrhoea was the most common AE (86% for both IM‐R and IM‐I patients), only 2% (n = 3) of IM‐R and 1% (n = 1) of IM‐I patients discontinued bosutinib because of diarrhoea (Table SV). Diarrhoea was typically of low severity and transient, with a median duration of 1 day per any grade event (IM‐R, 1 day; IM‐I, 2 days) and a median cumulative duration of 27 days (IM‐R, 33 days; IM‐I, 22 days). These events occurred early and incidence decreased over time (Fig SIII). Grade 3 diarrhoea was experienced by 29 (10%) patients (IM‐R, 10%; IM‐I, 11%), with no grade 4 events reported; these grade 3 events had a median onset of 11 (range, 1–1754) days and a median duration per event of 3 (1–26) days. Among 245 patients who experienced diarrhoea, 167 (68%) received concomitant medications (61%, loperamide; 4%, atropine and diphenoxylate), 14 (6%) had dose reductions and 39 (16%) had dose interruptions for diarrhoea management. Of patients with dose interruptions who were rechallenged with bosutinib (n = 38), only 1 (3%) discontinued because of diarrhoea. Predictors of time to first grade 3/4 diarrhoea were assessed based on the demographic and baseline factors described in Table 2 and the additional factors of concomitant medications for diarrhoea management at baseline and prior medical history of gastrointestinal disorders (defined as diarrhoea, Crohn disease, colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, fecal incontinence and proctitis). The only significant predictor of grade 3/4 diarrhoea was having a bosutinib‐sensitive baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutation [vs. no mutation; hazard ratio, 3·25 (95% CI, 1·03–10·22); P = 0·0444].

Thrombocytopenia (42%; grade 3/4, 26%), anaemia (27%; 11%) and neutropenia (16%; 9%) were the most common haematologic TEAEs; drug‐related events were experienced by 113 (40%), 51 (18%) and 43 (15%) patients, respectively. Median (range) time to onset of grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, anaemia or neutropenia (any cause) was 36 (6–1007), 231 (3–1767) and 63 (2–839) days, respectively; median durations of any grade AEs were 15 (1–1182), 17 (1–1373) and 17 (1–506) days. For affected patients, these TEAEs were effectively managed with dose interruptions (53%; 13%; 39%), dose reductions (38%, 9%, 20%) and concomitant medication (6%, 15%, 13%).

AEs of alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevations occurred in 25% (IM‐R, 23%; IM‐I, 28%) of patients and led to discontinuation in 2% (IM‐R, 2%; IM‐I, 4%). ALT/AST elevations occurred early in treatment [median time to first event, 35 (range, 3–1400) days (IM‐R, 36 days; IM‐I, 28 days)] and had a median duration of 26 (range, 1–1714) days per any grade event (IM‐R, 29 days; IM‐I, 13 days). Patients with events were managed by dose interruption [37% (IM‐R, 40%; IM‐I, 32%)], dose reductions [17% (IM‐R, 18%; IM‐I, 16%)] and/or concomitant medications [16% (IM‐R, 16%; IM‐I, 16%)]. The incidence of ALT elevations decreased over time on treatment (Fig SIV). Predictors of time to first liver‐related AE (overall and grade 3/4) were assessed based on the demographic and baseline factors described in Table 2 and the additional factors of concomitant medications for liver disorders at baseline (bile and liver therapies) and prior medical history of liver disorders [System Organ Class (SOC), Hepatobiliary Disorders (all preferred terms); SOC, Investigations (preferred terms: increased levels of ALT, AST, transaminases, conjugated bilirubin, blood bilirubin and hepatic enzymes and abnormal liver test)]. No significant associations between these factors and development of liver‐related AEs (overall or grade 3/4) were observed (P ≥ 0·0520).

Cardiac TEAEs (defined in Table SVI) occurred in 16% of patients. Using a narrower definition of cardiac TEAEs (SOC, Cardiac Disorders), incidence was 9% in year 1 [1 additional patient had a cardiac AE in year 1 (electrocardiogram QT prolonged, SOC Investigations) which was not summarized in the incidence of TEAEs for SOC Cardiac Disorders], 5% in year 2 [1 additional patient had a cardiac AE in year 2 (blood creatine phosphokinase MB increased, SOC Investigations)], 7% in year 3% and 5% in year 4. Cardiac AEs considered drug‐related were reported in 15/286 (5%) patients, most commonly (≥2 patients) angina pectoris (n = 3), pericardial effusion (n = 3) and palpitations (n = 2). Individual cardiac TEAEs (any grade) that occurred in ≥5% of patients aged <65 years (n = 223) or ≥65 years (n = 63) or with ≥5% difference between age groups were bradycardia (0·9% vs. 6·3%, respectively), congestive cardiac failure (0·9% vs. 6·3%) and cardiac failure (0% vs. 6·3%). Vascular TEAEs (defined in Table SVII) were reported in 14% (any grade) of patients (grade 3/4, 6%), most commonly hypertension (any grade, 7%; grade 3/4, 2%). No cases of peripheral arterial occlusive disease were reported.

Cross‐intolerance

Of 86 patients who permanently discontinued prior imatinib due to a grade 3/4 AE (4 IM‐I patients did not have the AE that led to IM intolerance recorded on the case report form), 62% experienced the same AE with bosutinib and 17% were cross‐intolerant (i.e, discontinued bosutinib due to the same AE that led to discontinuation of prior imatinib) (Table SVIII). The most common AEs leading to cross‐intolerance between bosutinib and prior imatinib were haematologic; however, most of the patients who discontinued prior imatinib due to thrombocytopenia [12/17 (71%)], neutropenia [11/13 (85%)] and anaemia [11/11 (100%)] did not discontinue bosutinib due to the same AEs. Of 7 patients who discontinued prior imatinib due to diarrhoea, only 1 discontinued bosutinib due to this AE. There were no deaths on bosutinib due to the same AE that led to intolerance to imatinib.

Discussion

This 4‐year follow‐up of an ongoing phase 1/2 study assessed the effect of patient‐ and treatment‐related factors on the long‐term efficacy and safety of second‐line bosutinib treatment following first‐line imatinib. The cumulative response rates (MCyR, 59%; CCyR, 49%) were close to those reported in the 2‐year analysis of this phase 1/2 study in patients receiving second‐line bosutinib (MCyR, 59%; CCyR, 48%), suggesting that most initial responses occur within 2 years from bosutinib treatment initiation (Gambacorti‐Passerini et al, 2014). Responses are durable, with 4‐year probabilities of maintaining a MCyR or CCyR at 4 years of 75% and 76%; estimated rates of on‐treatment PD/death (19%) and AP/BP transformation (4%) remained low after 4 years. Important study limitations include the short follow‐up duration of 30 days after treatment discontinuation for most assessments and the limited follow‐up for survival of 2 years after treatment discontinuation (per protocol).

The observation that age was not a significant predictor of cytogenetic response (except MCyR by 3 months) or survival outcomes is consistent with the results of a previous study demonstrating similar cytogenetic responses (Gugliotta et al, 2011) and survival outcomes (censoring deaths unrelated to CML) (Cortes et al, 2003) among older vs. younger patients with early CP CML receiving first‐line imatinib. Previous analyses in late‐phase CP CML patients with prior failure of IFNα therapy receiving imatinib showed an association between older age and poorer cytogenetic response, but not poorer survival outcomes (Cortes et al, 2003; Rosti et al, 2007). Notably, a previous study showed that a baseline ECOG PS of ≥1 at the start of second‐line TKI treatment (dasatinib or nilotinib) is predictive of poor event‐free and overall survival (Jabbour et al, 2011). In the present study, nearly all enrolled patients had baseline ECOG PS of 0 or 1, which may introduce bias because patients may be expected to have better long‐term outcomes. The finding that baseline Ph+ ratios ≤35% predict maintaining/attaining MCyR and CCyR at 3 and 6 months in patients receiving bosutinib is consistent with previous observations that a lower proportion of Ph+ metaphases is associated with higher MCyR and CCyR rates in patients receiving IM (Kantarjian et al, 2003), as well as longer OS and PFS (Hanfstein et al, 2012). BCR‐ABL1 transcript levels assessed between 3 and 18 months have also been shown to be significant predictors of response and survival (Hughes et al, 2010; Marin et al, 2012; El‐Metnawy et al, 2013). Moreover, among patients achieving a CCyR with IM, a ≥ 0·5‐log increase in BCR‐ABL1 expression resulted in an approximately 5‐fold increase in relapse‐risk vs. those without increased expression (Press et al, 2007). Consistent with the present study, a lower proportion of Ph+ metaphases was also observed to be predictive of response to second‐line dasatinib (Jabbour et al, 2009); other favourable prognostic factors included absence of T315I mutation, prior MCyR with IM, IM intolerance vs. resistance, no prior transplant and shorter time from CML diagnosis to initiation of dasatinib treatment (Jabbour et al, 2009). Baseline factors previously reported to be predictive of longer PFS in patients receiving second‐line nilotinib included attaining MCyR by 12 months, baseline haemoglobin level ≥120 g/L, basophils <4% and the absence of baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutations associated with nilotinib insensitivity (E255K/V, Y253H and F359C/V) (Jabbour et al, 2013).

The observation that older patients had more comorbidities at baseline and a higher incidence of certain commonly occurring nonhaematologic TEAEs (preferred terms: fatigue, decreased appetite, decreased weight, dyspnea and pleural effusion) is consistent with the results of a previous study demonstrating a higher incidence of TEAEs in older patients (Rosti et al, 2007) and with the observed increase in prevalence of comorbidities with age (Gugliotta et al, 2013). Notably, bosutinib‐insensitive baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutations were not significant predictors of MCyR or CCyR at any time point, consistent with the observation that bosutinib treatment was associated with MCyR across a spectrum of baseline mutations. Bosutinib‐insensitive baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutations were significant predictors of poorer survival up to 2 years, consistent with the results of a recent multivariate analysis showing that the absence of baseline BCR‐ABL1 mutations with low sensitivity to nilotinib is prognostic of PFS (Jabbour et al, 2013).

Treatment‐emergent AE rates in the 4‐year analysis of second‐line bosutinib are similar to those reported in the 2‐year analysis of this phase 1/2 trial [e.g, diarrhoea (86% vs. 84%, respectively), nausea (46% vs. 45%), rash (36% vs. 34%) and vomiting (37% vs. 37%)] (Gambacorti‐Passerini et al, 2014; Kantarjian et al, 2014). Newly occurring haematologic and non‐haematologic AEs generally decreased after the first treatment year except for increased blood creatinine. Further analysis of renal AEs with long‐term bosutinib treatment is ongoing. Discontinuations due to AEs were most common in the first year (17%). These findings suggest that careful monitoring and prompt management of AEs may help patients remain long‐term on effective treatment.

Although diarrhoea was the most common toxicity, most events occurred early, were of short duration and rarely resulted in discontinuation. Unexpectedly, the presence of a bosutinib‐sensitive baseline mutation was identified as a predictor of grade 3/4 diarrhoea (P = 0·0444); however, given the relatively high P‐value and because there was no adjustment for multiple testing, there is no strong statistical evidence to suggest a correlation between baseline mutation sensitivity and diarrhoea. This relationship will be further investigated as part of the planned Bosutinib Dose Optimization (BODO) study in CML patients receiving second‐line bosutinib after failure of prior nilotinib or dasatinib. Although common, liver‐related AEs led to discontinuations in few (2%) patients and were readily managed by dose modification and/or concomitant medications. As liver‐related AEs and discontinuations due to these AEs most frequently occurred in treatment year 1, hepatic enzyme tests should be performed monthly for the first 3 months and when clinically indicated. The rate of discontinuation due to any AE may be accounted for by the observation that nearly half [n = 28 (42%)] of the 67 patients who discontinued due to an AE did so without attempting dose reduction to <500 mg/day for the AE that led to discontinuation. The present results also suggest a limited effect of dose reduction due to AEs on response.

In conclusion, bosutinib continues to demonstrate durable efficacy and manageable toxicity in CP CML patients following IM‐R or IM‐I after ≥48 months of follow‐up. The baseline factors predictive of long‐term patient outcomes identified here may allow identification of patient subgroups with Ph+ CML who might benefit optimally from bosutinib treatment. Overall, these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of bosutinib as second‐line therapy in IM‐R or IM‐I CP CML patients.

Competing Interests

THB has participated in advisory boards and satellite symposia for Ariad, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis and Pfizer; he has also received research funding from Novartis and holds a patent on the combination of imatinib with hypusination inhibitors. JEC has received research support and is a consultant for Ariad, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. HJK has received research funding from and attended compensated advisory boards for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, Teva, Pfizer and Ariad. HMK has received research funding from Pfizer. DWK received research funding from Ariad, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis and Pfizer; served as a consultant/advisor for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis and Pfizer; and participated on the Speakers’ bureau for and received honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Novartis. PS has served as an advisor/consultant for and received honoraria from Ariad, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis and Pfizer. MGC is a former employee of Pfizer. MS, KT and EL are current employees of Pfizer. CG‐P has received research funding from Pfizer and has served as an advisor for Pfizer and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. JHL has received research funding and consultant or other fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, Teva, Pfizer and Ariad and lecture fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Novartis.

Supporting information

Fig S1. Cumulative incidence of (A) CCyR in all evaluable patients (responders and nonresponders) over time adjusting for the competing risk of treatment discontinuation without the event and (B) duration of CCyR among responders.

Fig S2. Attained/Maintained MCyR by Baseline BCR‐ABL1 Mutational Status Among Patients Evaluable for MCyR.

Fig S3. Incidence of diarrhea TEAEs over time

Fig S4. Incidence of elevated alanine aminotransferase TEAEs Over time.

Table SI. Demographics and disease characteristics.

Table SII. Treatment summary.

Table SIII. Cytogenetic response before and after bosutinib dose reduction.

Table SIV. Adverse events resulting in treatment discontinuation in ≥1% of patients overall and reasons for treatment discontinuation over time.

Table SV. Characteristics and management of diarrhea TEAEs.

Table SVI. MedDRA terms used in the cardiac toxicity analyses.

Table SVII. MedDRA terms used in the vascular toxicity analyses.

Table SVIII. AEs, dose delays/reductions, and cross‐intolerance in patients intolerant to prior imatinib.

Acknowledgements

Funding Support: This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

The authors thank all of the patients who have contributed to this study and their relatives. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Editorial support was provided by Simon J. Slater, PhD, and Cynthia L. Gobbel, PhD, of Complete Healthcare Communications, Inc. (Chadds Ford, PA, USA) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

THB, JEC, HJK, D‐WK, PS, CGP and JHL contributed substantially to the research design, acquisition and interpretation of the data. MGC, KT and MS contributed substantially to the research design and interpretation of the data. EL performed statistical analyses. All authors assisted in the writing and/or critical review of the manuscript, and all authors provided final approval of the manuscript for submission.

References

- Baccarani, M. , Saglio, G. , Goldman, J. , Hochhaus, A. , Simonsson, B. , Appelbaum, F. , Apperley, J. , Cervantes, F. , Cortes, J. , Deininger, M. , Gratwohl, A. , Guilhot, F. , Horowitz, M. , Hughes, T. , Kantarjian, H. , Larson, R. , Niederwieser, D. , Silver, R. , Hehlmann, R. & European LeukemiaNet (2006) Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood, 108, 1809–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolovic, K. , Balabanov, S. , Hartmann, U. , Komor, M. , Boehmler, A.M. , Buhring, H.J. , Mohle, R. , Hoelzer, D. , Kanz, L. , Hofmann, W.K. & Brummendorf, T.H. (2004) Inhibitory effect of imatinib on normal progenitor cells in vitro . Blood, 103, 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blay, J.Y. & von Mehren, M. (2011) Nilotinib: a novel, selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Seminars in Oncology, 38, S3–S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. (2007) Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) In: Pharmacovigilance. 2nd edn (ed. RD Mann. & EB Andrews.), pp. 168–183. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, J. , Talpaz, M. , O'Brien, S. , Giles, F. , Beth Rios, M. , Shan, J. , Faderl, S. , Garcia‐Manero, G. , Ferrajoli, A. , Wierda, W. & Kantarjian, H. (2003) Effects of age on prognosis with imatinib mesylate therapy for patients with Philadelphia chromosome‐positive chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer, 98, 1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, J.E. , Kantarjian, H.M. , Brummendorf, T.H. , Kim, D.W. , Turkina, A.G. , Shen, Z.X. , Pasquini, R. , Khoury, H.J. , Arkin, S. , Volkert, A. , Besson, N. , Abbas, R. , Wang, J. , Leip, E. & Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. (2011) Safety and efficacy of bosutinib (SKI‐606) in chronic phase Philadelphia chromosome‐positive chronic myeloid leukemia patients with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Blood, 118, 4567–4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Metnawy, W.H. , Mattar, M.M. , El‐Nahass, Y.H. , Samra, M.A. , Abdelhamid, H.M. , Abdlfattah, R.M. & Hamed, A.R. (2013) Predictive Value of Pretreatment BCR‐ABL(IS) Transcript level on Response to Imatinib Therapy in Egyptian Patients with Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CPCML). International Journal of Biomedical Sciences, 9, 48–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. , Tornaghi, L. , Cavagnini, F. , Rossi, P. , Pecori‐Giraldi, F. , Mariani, L. , Cambiaghi, N. , Pogliani, E. , Corneo, G. & Gnessi, L. (2003) Gynaecomastia in men with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib. Lancet, 361, 1954–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. , Brummendorf, T.H. , Kim, D.W. , Turkina, A.G. , Masszi, T. , Assouline, S. , Durrant, S. , Kantarjian, H.M. , Khoury, H.J. , Zaritskey, A. , Shen, Z.X. , Jin, J. , Vellenga, E. , Pasquini, R. , Mathews, V. , Cervantes, F. , Besson, N. , Turnbull, K. , Leip, E. , Kelly, V. & Cortes, J.E. (2014) Bosutinib efficacy and safety in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia after imatinib resistance or intolerance: minimum 24‐month follow‐up. American Journal of Hematology, 89, 732–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnoni, A. , Marech, I. , Silvestris, N. , Vacca, A. & Lorusso, V. (2011) Dasatinib: an anti‐tumour agent via Src inhibition. Current Drug Targets, 12, 563–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugliotta, G. , Castagnetti, F. , Palandri, F. , Breccia, M. , Intermesoli, T. , Capucci, A. , Martino, B. , Pregno, P. , Rupoli, S. , Ferrero, D. , Gherlinzoni, F. , Montefusco, E. , Bocchia, M. , Tiribelli, M. , Pierri, I. , Grifoni, F. , Marzocchi, G. , Amabile, M. , Testoni, N. , Martinelli, G. , Alimena, G. , Pane, F. , Saglio, G. , Baccarani, M. & Rosti, G. & Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto CML Working Party . (2011) Frontline imatinib treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: no impact of age on outcome, a survey by the GIMEMA CML Working Party. Blood, 117, 5591–5599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugliotta, G. , Castagnetti, F. , Fogli, M. , Cavo, M. , Baccarani, M. & Rosti, G. (2013) Impact of comorbidities on the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia with tyrosine‐kinase inhibitors. Expert Review of Hematology, 6, 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanfstein, B. , Muller, M.C. , Hehlmann, R. , Erben, P. , Lauseker, M. , Fabarius, A. , Schnittger, S. , Haferlach, C. , Gohring, G. , Proetel, U. , Kolb, H.J. , Krause, S.W. , Hofmann, W.K. , Schubert, J. , Einsele, H. , Dengler, J. , Hanel, M. , Falge, C. , Kanz, L. , Neubauer, A. , Kneba, M. , Stegelmann, F. , Pfreundschuh, M. , Waller, C.F. , Branford, S. , Hughes, T.P. , Spiekermann, K. , Baerlocher, G.M. , Pfirrmann, M. , Hasford, J. , Saussele, S. & Hochhaus, A. , SAKK & German CML Study Group . (2012) Early molecular and cytogenetic response is predictive for long‐term progression‐free and overall survival in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Leukemia, 26, 2096–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.P. , Hochhaus, A. , Branford, S. , Muller, M.C. , Kaeda, J.S. , Foroni, L. , Druker, B.J. , Guilhot, F. , Larson, R.A. , O'Brien, S.G. , Rudoltz, M.S. , Mone, M. , Wehrle, E. , Modur, V. , Goldman, J.M. , Radich, J.P. & Investigators IRIS (2010) Long‐term prognostic significance of early molecular response to imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: an analysis from the International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS). Blood, 116, 3758–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, E. & Williams, C. (2013) Treatment‐, patient‐, and disease‐related factors and the emergence of adverse events with tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pharmacotherapy, 33, 868–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isfort, S. , Amsberg, G.K. , Schafhausen, P. , Koschmieder, S. & Brummendorf, T.H. (2014) Bosutinib: a novel second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Recent Results in Cancer Research, 201, 81–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, E. , Bahceci, E. , Zhu, C. , Lambert, A. & Cortes, J. (2009) Predictors of Long‐Term Cytogenetic Response Following Dasatinib Therapy of Patients with Chronic‐Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML‐CP). In: American Society of Hematology (ASH) 2009 Annual Meeting, Abstract 3296, New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, E. , Kantarjian, H. , O'Brien, S. , Shan, J. , Garcia‐Manero, G. , Wierda, W. , Ravandi, F. , Borthakur, G. , Rios, M.B. & Cortes, J. (2011) Predictive factors for outcome and response in patients treated with second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after imatinib failure. Blood, 117, 1822–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, E. , le Coutre, P.D. , Cortes, J. , Giles, F. , Bhalla, K.N. , Pinilla‐Ibarz, J. , Larson, R.A. , Gattermann, N. , Ottmann, O.G. , Hochhaus, A. , Hughes, T.P. , Saglio, G. , Radich, J.P. , Kim, D.W. , Martinelli, G. , Reynolds, J. , Woodman, R.C. , Baccarani, M. & Kantarjian, H.M. (2013) Prediction of outcomes in patients with Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with nilotinib after imatinib resistance/intolerance. Leukemia, 27, 907–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian, H. , Talpaz, M. , O'Brien, S. , Giles, F. , Rios, M.B. , White, K. , Garcia‐Manero, G. , Ferrajoli, A. , Verstovsek, S. , Wierda, W. , Kornblau, S. & Cortes, J. (2003) Prediction of initial cytogenetic response for subsequent major and complete cytogenetic response to imatinib mesylate therapy in patients with Philadelphia chromosome‐positive chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer, 97, 2225–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian, H.M. , Cortes, J.E. , Kim, D.W. , Khoury, H.J. , Brummendorf, T.H. , Porkka, K. , Martinelli, G. , Durrant, S. , Leip, E. , Kelly, V. , Turnbull, K. , Besson, N. & Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. (2014) Bosutinib safety and management of toxicity in leukemia patients with resistance or intolerance to imatinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood, 123, 1309–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveen, P. , Pekny, M. , Gebre‐Medhin, S. , Swolin, B. , Larsson, E. & Betsholtz, C. (1994) Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes and Development, 8, 1875–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. (2008) Src‐family kinases in the development and therapy of Philadelphia chromosome‐positive chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia and Lymphoma, 49, 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin, D. , Ibrahim, A.R. , Lucas, C. , Gerrard, G. , Wang, L. , Szydlo, R.M. , Clark, R.E. , Apperley, J.F. , Milojkovic, D. , Bua, M. , Pavlu, J. , Paliompeis, C. , Reid, A. , Rezvani, K. , Goldman, J.M. & Foroni, L. (2012) Assessment of BCR‐ABL1 transcript levels at 3 months is the only requirement for predicting outcome for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press, R.D. , Galderisi, C. , Yang, R. , Rempfer, C. , Willis, S.G. , Mauro, M.J. , Druker, B.J. & Deininger, M.W. (2007) A half‐log increase in BCR‐ABL RNA predicts a higher risk of relapse in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia with an imatinib‐induced complete cytogenetic response. Clinical Cancer Research, 13, 6136–6143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli, S. , Piazza, R. , Rostagno, R. , Magistroni, V. , Perini, P. , Marega, M. , Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. & Boschelli, F. (2009) Activity of bosutinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib against 18 imatinib‐resistant BCR/ABL mutants. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 469–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli, S. , Boschelli, F. , Perini, P. , Pirola, A. , Viltadi, M. & Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. (2010) Synergistic activity of the Src/Abl inhibitor bosutinib in combination with imatinib. Leukemia, 24, 1223–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli, S. , Mologni, L. , Rostagno, R. , Piazza, R. , Magistroni, V. , Ceccon, M. , Viltadi, M. , Flynn, D. & Gambacorti‐Passerini, C. (2012) Three novel patient‐derived BCR/ABL mutants show different sensitivity to second and third generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors. American Journal of Hematology, 87, E125–E128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosti, G. , Iacobucci, I. , Bassi, S. , Castagnetti, F. , Amabile, M. , Cilloni, D. , Poerio, A. , Soverini, S. , Palandri, F. , Rege Cambrin, G. , Iuliano, F. , Alimena, G. , Latagliata, R. , Testoni, N. , Pane, F. , Saglio, G. , Baccarani, M. & Martinelli, G. (2007) Impact of age on the outcome of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in late chronic phase: results of a phase II study of the GIMEMA CML Working Party. Haematologica, 92, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, A.S. , Kantarjian, H. , Cortes, J. , O'Brien, S. & Talpaz, M. (2003) Imatinib mesylate causes hypopigmentation in the skin. Cancer, 98, 2483–2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller, C.F. (2010) Imatinib mesylate. Recent Results in Cancer Research, 184, 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1. Cumulative incidence of (A) CCyR in all evaluable patients (responders and nonresponders) over time adjusting for the competing risk of treatment discontinuation without the event and (B) duration of CCyR among responders.

Fig S2. Attained/Maintained MCyR by Baseline BCR‐ABL1 Mutational Status Among Patients Evaluable for MCyR.

Fig S3. Incidence of diarrhea TEAEs over time

Fig S4. Incidence of elevated alanine aminotransferase TEAEs Over time.

Table SI. Demographics and disease characteristics.

Table SII. Treatment summary.

Table SIII. Cytogenetic response before and after bosutinib dose reduction.

Table SIV. Adverse events resulting in treatment discontinuation in ≥1% of patients overall and reasons for treatment discontinuation over time.

Table SV. Characteristics and management of diarrhea TEAEs.

Table SVI. MedDRA terms used in the cardiac toxicity analyses.

Table SVII. MedDRA terms used in the vascular toxicity analyses.

Table SVIII. AEs, dose delays/reductions, and cross‐intolerance in patients intolerant to prior imatinib.