Abstract

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) mediate both image-forming vision and non-image-forming visual responses such as pupillary constriction and circadian photoentrainment. Five types of ipRGCs, named M1–M5, have been discovered in rodents. To further investigate their photoresponse properties, we made multielectrode array spike recordings from rat ipRGCs, classified them into M1, M2/M4, and M3/M5 clusters, and measured their intrinsic, melanopsin-based responses to single and flickering light pulses. Results showed that ipRGC spiking can track flickers up to ∼0.2 Hz in frequency and that flicker intervals between 5 and 14 s evoke the most spikes. We also learned that melanopsin’s integration time is intensity and cluster dependent. Using these data, we constructed a mathematical model for each cluster’s intrinsic photoresponse. We found that the data for the M1 cluster are best fit by a model that assumes a large photoresponse, causing the cell to enter depolarization block. Our models also led us to hypothesize that the M2/M4 and M3/M5 clusters experience comparable photoexcitation but that the M3/M5 cascade decays significantly faster than the M2/M4 cascade, resulting in different response waveforms between these clusters. These mathematical models will help predict how each ipRGC cluster might respond to stimuli of any waveform and could inform the invention of lighting technologies that promote health through melanopsin stimulation.

Keywords: melanopsin, retina, light response, electrophysiology, mathematical modeling

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) are output neurons of the retina that contain the photopigment melanopsin (Berson et al. 2002; Hattar et al. 2002; Provencio et al. 1998), which generates excitatory responses to light by signaling through an invertebrate-like phototransduction cascade (Graham et al. 2008; Xue et al. 2011). Among the many behavioral roles mediated by ipRGCs are the pupillary light reflex, neuroendocrine regulation, entrainment of circadian rhythms to light/dark cycles, and aspects of conscious visual perception (Brown et al. 2012; Ecker et al. 2010; Freedman et al. 1999; Lucas et al. 2001; Lucas and Foster 1999; Schmidt et al. 2014; Zaidi et al. 2007). Five types of ipRGCs, named M1–M5, have been discovered in mice (Ecker et al. 2010; Viney et al. 2007) and rats (Reifler et al. 2015). Although all ipRGCs generate intrinsic photoresponses most sensitive to ∼480 nm (Tu et al. 2005), these responses show type-dependent differences (Reifler et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2014) that presumably reflect functional differences; e.g., the M1 type mediates circadian photoentrainment and pupillary reflexes (Chen et al. 2011), whereas the M4 type contributes to contrast sensitivity (Schmidt et al. 2014). All previous comparisons of the different cell types’ intrinsic light responses employed whole cell recording so that recorded cells could be dye-filled and their identities revealed through morphological visualization (Ecker et al. 2010; Estevez et al. 2012; Reifler et al. 2015; Schmidt and Kofuji 2009, 2011; Zhao et al. 2014). However, whole cell recordings of rodent ganglion cells are stable for relatively short durations (typically <1 h). Consequently, these studies only tested a limited number of fairly short light steps, and it remained unknown how ipRGCs might respond to more complicated stimuli.

Our recent demonstration that rat M1 cells, M2/M4, cells and M3/M5 cells generate significantly different melanopsin-based spiking photoresponses (Reifler et al. 2015) has made it possible to distinguish these cell groups in “blind” multielectrode array (MEA) spike recordings, which are longer lasting than whole cell recordings (Meister et al. 1994). In the current study, we took advantage of the longevity of MEA recordings to characterize how the three ipRGC clusters respond to longer stimuli with different temporal properties, specifically, single light steps of various durations and intensities, and flickering flashes of different frequencies and intensities. However, these are still far simpler than most commonly encountered stimuli. Thus we then used the data to develop cluster-specific mathematical models of melanopsin phototransduction, which can be used to predict how the three cell clusters might respond to many arbitrary stimulus waveforms. Although mathematical models have been constructed for ipRGC-mediated visual behaviors such as the pupillary light reflex and circadian photoentrainment (Kronauer et al. 1999; Longtin and Milton 1989; Rea et al. 2005), we focused on ipRGCs’ spiking responses to light. In addition to facilitating photoresponse predictions, the simple models presented in this article give some insights into the underlying causes of ipRGCs’ response diversity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental procedures.

All procedures were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals. Adult Sprague-Dawley rats of both sexes between 2 and 4 mo of age were used. Animals were housed in a 12:12-h light-dark environment, with all electrophysiological recordings made during the light phase. After overnight dark adaptation, each rat was euthanized using CO2 followed by pneumothorax. Under dim red light, both eyes were harvested and the retinas isolated. A piece of retina was flattened with the ganglion cell side down on an MEA (Multi Channel Systems, Reutlingen, Germany) and superfused with 32°C Ames’ medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 50 μM l-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (l-AP4), 40 μM 7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX), and 25 μM d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5; Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN); these glutamate analogs block rod/cone signaling to the inner retina, thereby enabling the selective detection of melanopsin-based photoresponses in ipRGCs (Wong et al. 2007).

After each piece of retina had been superfused in darkness for 40–45 min, full-field 480-nm stimulus light was presented using a monochromator (Optical Building Blocks, Edison, NJ), following two protocols: 1) single light steps presented for 10, 50, and 200 s, and 2) twenty 1-s pulses separated by 0, 1, 5, 14, and 29 s of darkness. Both protocols were repeated for light at intensities 12.9 log, 13.9 log, and 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1. Because pilot experiments revealed time-dependent reductions in photoresponse amplitude, stimuli were presented in the orders shown in Fig. 1, A and B, to reduce the bias for or against any stimulus. In each experiment measuring single-step responses, only one of the three intensities was tested, and the entire sequence shown in Fig. 1A was followed, with interstimulus intervals ranging from 20 to 30 min. The two 10-s responses were averaged, and so were the two 50-s responses. In the experiments studying responses to the flickering pulses, each piece of retina was presented with one of the stimulus intensities in either sequence 1 or sequence 2 shown in Fig. 1B, with interstimulus intervals between 15 and 30 min. Each intensity was tested in both sequences using different retinas, and comparable numbers of cells were recorded for both sequences.

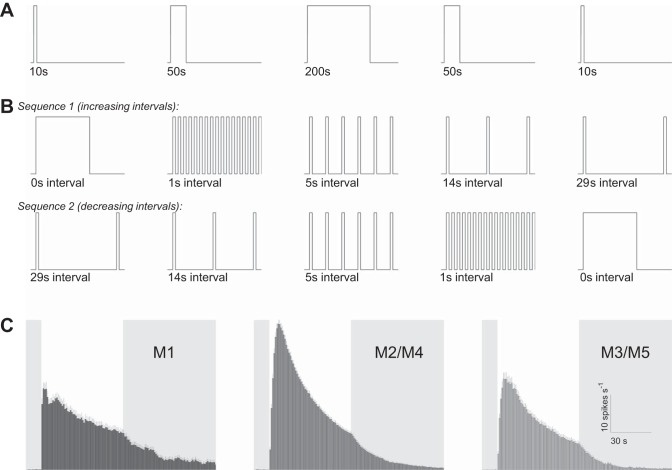

Fig. 1.

Stimulus protocols and clustering of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell (ipRGC) types. A: lighting protocol for the single-light-step experiments. This protocol was applied to each piece of retina, at one stimulus intensity (12.9 log, 13.9 log, or 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1). B: lighting protocol for the experiments testing responses to flickering lights, with the first 40 s of each stimulus shown. Each retina was tested with one of these sequences, at one stimulus intensity. C: grouping of multielectrode array (MEA)-recorded ipRGCs’ responses to 60-s 15.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 light (white vertical bars) into 3 clusters, as recommended by Reifler et al. (2015). M1 and M3/M5 cells’ responses are smaller than M2/M4 cells’ responses, and M1 cells respond faster than the other 2 clusters. All error bars represent SE.

At the conclusion of each experiment, the retina was exposed to 60 s of 15.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 to induce robust intrinsic light responses in all ipRGCs. Spikes were sorted using Offline Sorter software (Plexon, Dallas, TX). Using the responses to the 60-s 15.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 light, each unit was assigned to one of three clusters: M1, which generates spiking responses with short latencies but relatively low firing rates; M2/M4, whose responses have longer latencies but higher firing rates; and M3/M5, which have long-latency and low-firing-rate responses (Reifler et al. 2015). M1 cells’ uniquely fast intrinsic photoresponses enabled them to be easily identified. In many retinas, the slow-responding cells formed two obvious clusters with different peak response amplitudes; the higher amplitude cluster was classified as M2/M4, and the other as M3/M5. In some retinas, such clear dichotomy was not seen; for these, we categorized the units with larger peak amplitudes than the M1 cells’ as M2/M4 cells, and the remaining slow-responding units as M3/M5. Thus the M2/M4 cluster could have included some M3/M5 cells with unusually high-amplitude responses, whereas the M3/M5 cluster could have included some M2/M4 cells with unusually low-amplitude responses, although most cells in these clusters were probably correctly assigned. This clustering was initially done manually and later automated using k-means clustering. The different clusters’ averaged responses to the 60-s 15.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 light are shown in Fig. 1C.

Part of the mathematical modeling was based on whole cell recordings, and detailed methods for these recordings were previously described (Reifler et al. 2015). Briefly, whole cell recordings were made from randomly selected ganglion cells in Sprague-Dawley rat eyecups superfused with Ames’ medium containing 50 μM l-AP4, 40 μM DNQX, and 25 μM d-AP5, to find cells generating melanopsin-driven light responses. The internal solution contained (in mM) 120 K-gluconate, either 9 Neurobiotin-Cl or 5 NaCl plus 4 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 EGTA, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, 7 Tris-phosphocreatine, 0.1% Lucifer yellow, and KOH to set pH at 7.3. Stimuli were full-field 480-nm light. Cellular morphology was visualized through either streptavidin staining of Neurobiotin or immunohistochemistry against Lucifer yellow and was used to determine cell type.

Mathematical modeling.

MEA-recorded spike trains were imported into MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Photoresponse and firing were modeled using a system of ordinary differential equations, and parameters for the model which best matched the data were identified using MATLAB’s nlinfit method.

RESULTS

Responses to single light steps.

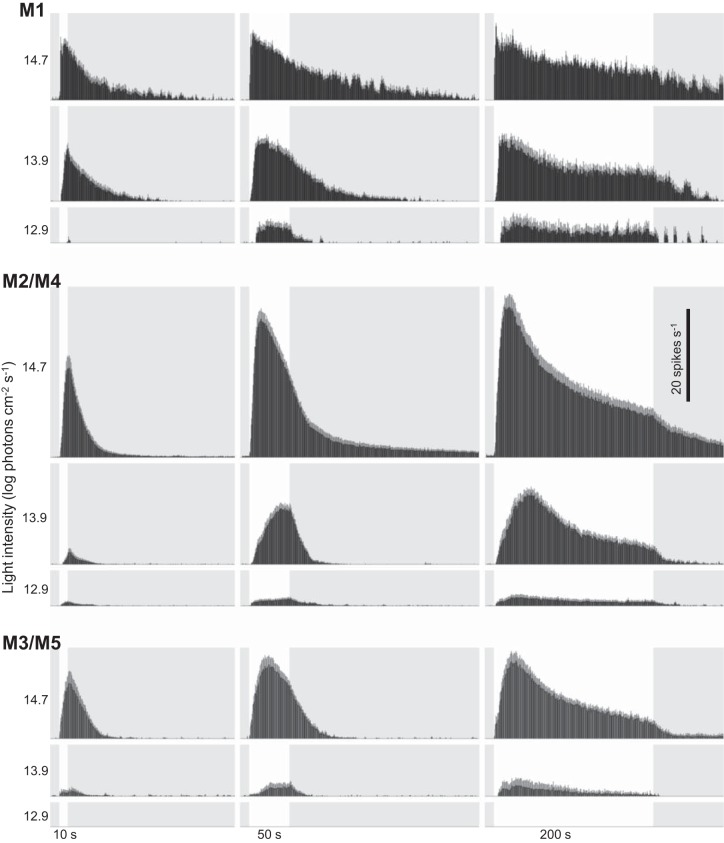

The three cell clusters’ intrinsic responses to the single light steps of different durations (10, 50, and 200 s) are given in Fig. 2. Several features common to all clusters are apparent. First, all responses were remarkably sustained: once a response started, it lasted throughout the remainder of the light step, and it continued for many seconds after stimulus offset. Second, the 10-s responses kept rising until the end of the light step, after which they decayed toward the baseline. Third, the 200-s responses and most 50-s responses peaked during the light step before gradually decaying for the rest of the light. Fourth, for each stimulus duration, the overall firing (both total response and peak firing rate) increased as stimulus intensity increased. Finally, as intensity increased, all cell clusters tended to reach peak firing rate faster.

Fig. 2.

Results of the single-light-step experiments. Histograms show averaged responses of the M1, M2/M4, and M3/M5 clusters to 10, 50, and 200 s of light (white vertical bars) at 3 stimulus intensities. Each histogram column has a width of 1 s.

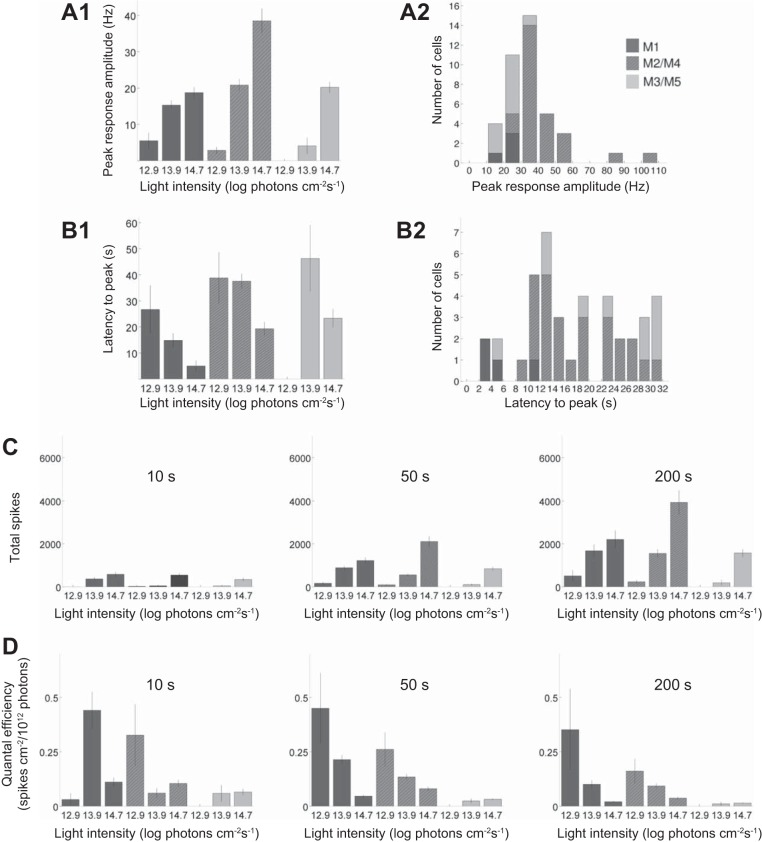

Cluster-specific quantifications are shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3, A and B, quantifies the peak amplitudes and latencies of the 200-s responses. All clusters generated larger responses as intensity increased (Fig. 3A1). At the lowest intensity (12.9 log photons cm−2·s−1), the M1 cluster’s response had the highest peak amplitude, whereas at the highest intensity (14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1), the M2/M4 cluster responded most strongly. In fact, at 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1, nearly all the cells with peak firing rates >30 spikes/s were M2/M4 (Fig. 3A2). In terms of latency to peak, the M1 cluster reached peak firing faster than M2/M4 and M3/M5 at all light intensities (Fig. 3B1). At the highest intensity, all M1 cells’ responses peaked within 12 s of light presentation, whereas most M2/M4 and M3/M5 cells took longer than 12 s (Fig. 3B2).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the single-light-step responses. A: peak response amplitude. A1: averaged peak firing rate plotted as a function of light intensity. Cells that did not fire are included in this computation, with peak amplitude set at 0. A2: distribution of the cells responding to the 200-s 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 stimulus. B: timing of the peak response. B1: latency to peak plotted as a function of light intensity. B2: distribution of peak latencies for responses to the 200-s 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 stimulus. Cells that did not fire are not included in either plot. C: the total number of light-induced spikes increased with increasing light intensity. Cells that did not spike are included, with spike number set at 0. D: quantal efficiency, calculated by dividing the total number of spikes (C) by the number of photons in the stimulus.

Figure 3, C and D, quantifies two additional aspects of the single-light-step responses for all three stimulus durations. Within each cell cluster, the total number of spikes increased as duration or intensity increased (Fig. 3C). By contrast, for each cell cluster, quantal efficiency (total spike count divided by total photon count) usually decreased as duration increased (Fig. 3D). Quantal efficiency also tended to decrease as stimulus intensity increased, suggesting that, for example, a 10-fold increase in photon count yielded fewer than 10 times the spikes.

Responses to repetitive light pulses.

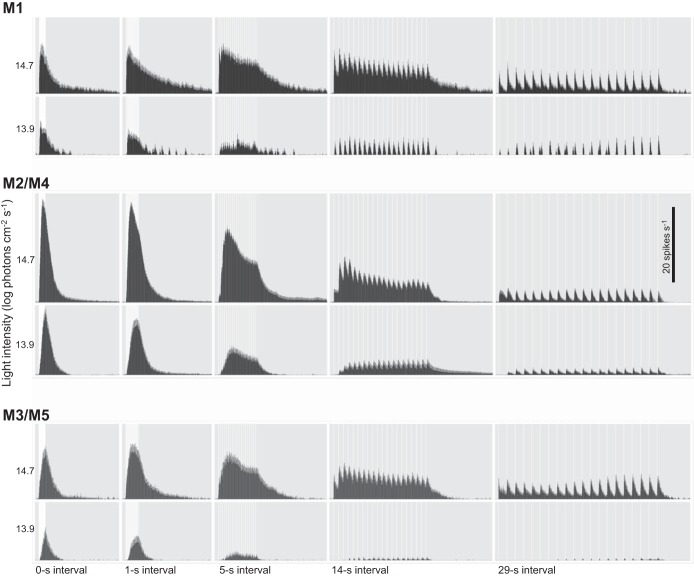

Figure 4 shows averaged responses to trains of twenty 1-s light pulses with different interpulse intervals: 0, 1, 5, 14, and 29 s. Although these stimuli were tested at 12.9 log, 13.9 log, and 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1, the lowest intensity activated so few cells that it was excluded from further analysis. Several cluster-independent generalizations can be discerned from these spike histograms. As expected, for all five stimuli, the 14.7 log intensity evoked more spikes than the 13.9 log intensity. Moreover, light adaptation was apparent at 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1, since most responses decayed during the stimulus train after peaking, although it was less pronounced or even absent at the lower intensity. In addition, even though the five stimuli at each intensity contained the same number of photons, they evoked clearly distinct responses. For example, the five stimuli evoked different spike counts. Clear tracking of individual pulses was absent at the 1-s interval but evident at the longer intervals. Peak response amplitudes declined as the interval increased, reflecting a decrease in the summation of pulse responses.

Fig. 4.

Results of the flicker experiments. Histograms show averaged responses of the M1, M2/M4, and M3/M5 clusters to twenty 1-s light pulses (white vertical bars), separated by 0, 1, 5, 14, and 29 s of darkness, at 2 intensities. Each histogram column has a bin width of 1 s.

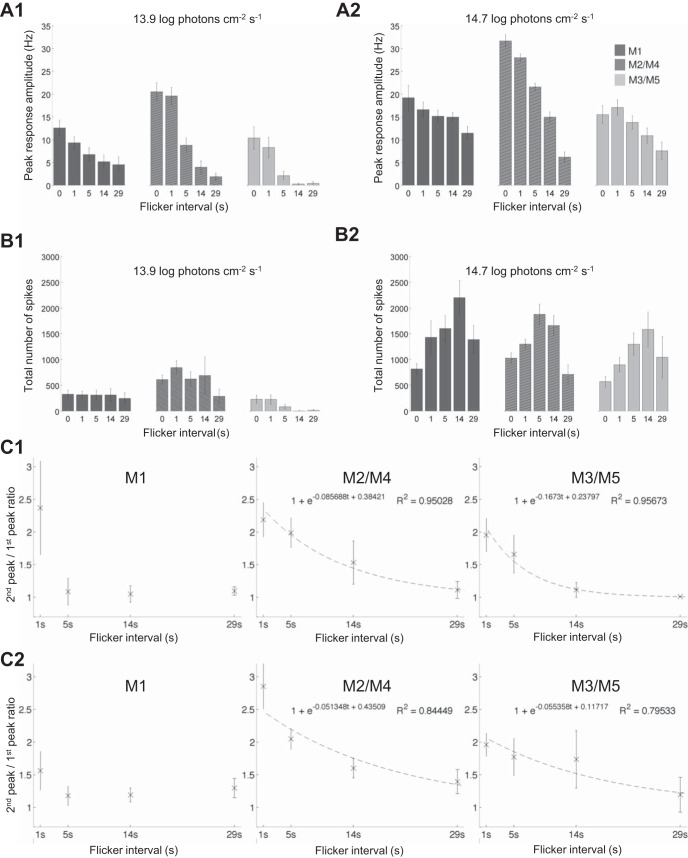

Several aspects of the flicker responses are quantified in Fig. 5. Peak response amplitudes are plotted as a function of interpulse interval in Fig. 5, A1 (13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1) and A2 (14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1). At the lower intensity, all clusters’ peak amplitudes decreased rapidly as the interval increased (Fig. 5A1), but at the higher intensity, how peak firing rate varied with interval was cluster dependent. Consistent with the single-step responses shown in Figs. 1C and 2, the flicker with 0-s intervals (which was essentially a 20-s light step) evoked the highest peak response from M2/M4 cells. However, as the interval increased, M2/M4 cells’ peak amplitudes dropped far more rapidly than those of M1 and M3/M5 cells. Consequently, the peak amplitude difference between the 0-s-interval and 29-s-interval flickers was cluster dependent: for M2/M4, the 29-s-interval response was less than one-quarter of the amplitude of the 0-s-interval response, but for M1 and M3/M5, the 29-s-interval response was more than one-half the amplitude of the 0-s-interval response. Thus, at the 29-s interval, M2/M4 cells had the lowest peak firing rate among the three ipRGC clusters (Fig. 5A2). Intensity-dependent differences were also observed for total spike count. At 13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1, the lowest interpulse intervals (0 and 1 s) tended to evoke the most spikes (Fig. 5B1), but at 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1, the most effective flicker intervals were 5 and 14 s (Fig. 4B2).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of the flicker responses. A: peak amplitudes of responses to the 13.9 log (A1) and 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 flickers (A2), plotted as a function of interpulse interval. Cells that did not respond are included, with response amplitude set at 0. B: total spikes evoked by the 13.9 log (B1) and 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 stimuli (B2). Cells that did not spike are included, with spike number set at 0. C: estimating integration time using responses to the 13.9 log (C1) and 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 flickers (C2). The peak firing rate during the second flicker cycle that evoked a response was divided by that during the first response-inducing cycle to compute the 2nd peak-to-1st peak ratio. This ratio decreased toward 1 as the interval between the 2 light pulses increased. The dashed lines represent first-order exponential decay fits to the data.

In the final analysis, we used the flicker responses to estimate the various cell clusters’ integration times. If two light pulses are close enough to evoke responses that summate, the peak firing rate during the second flicker cycle should be higher than that during the first cycle, but as the interpulse interval increases, the extent of summation and hence the difference between the two response amplitudes should decrease. Thus we plotted the ratio between the responses to the first two response-inducing pulses in the flicker as a function of interpulse interval (Fig. 5C). At 13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1 (Fig. 5C1), M1 cells’ 2nd peak-to-1st peak ratio dropped rapidly toward 1, whereas the other two clusters’ ratios dropped more gradually, suggesting that M1 has the shortest integration time at this intensity. The data points for M2/M4 and M3/M5 could be fitted reasonably well with single-exponential decays, with time constants of 11.70 and 5.98 s, respectively. Extrapolating the fitted curves showed that the 2nd peak-to-1st peak ratio dropped to 1.01 at 58- and 29-s interpulse intervals for the M2/M4 and M3/M5 clusters, respectively. In contrast, at 14.9 log photons cm−2·s−1 (Fig. 5C2), all three clusters’ 2nd peak-to-1st peak ratio dropped more slowly and remained higher than 1 even at the 29-s interval. The M2/M4 and M3/M5 data could again be fitted well with single-exponential decays, which had time constants of 19.47 and 18.06 s, and dropped to 1.01 at 98 and 85 s, respectively. In conclusion, all three cell clusters’ integration times were longer at the higher stimulus intensity.

Mathematical modeling of the single-step responses.

The general mathematical model developed to describe the intrinsic photoresponse for all three ipRGC clusters is

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where n is the fraction of activated melanopsin, c is the signaling cascade that follows, and y is a scaled version of the current induced by the cascade. Light intensity is denoted by I, and α(I) represents the light dependence of melanopsin’s activation rate.

In Eq. 1, α(1 − n) is the rate at which light activates melanopsin in the excitable state, which is represented as a fraction by 1 − n, and β is the rate at which the photopigment is returned (e.g., by an isomerase) from the activated state to the excitable state. The parameter k1 in Eq. 2 scales the rate of activation of the excitable photopigment for a cascade response, and k2 is the rate of decay of the cascade response. The parameters k3 and k4 are the rates at which ion channels open and close in response to the cascade, respectively. The form of Eq. 3 assumes available ion channels are abundant. Of all parameters, only α is chosen to be light dependent.

The drive to the cascade is proportional to α(1 − n), rather than n, in keeping with the “prompt response” model, which has been described in detail elsewhere (Kronauer et al. 1999). Briefly, choosing α(1 − n) as the input to the cascade corresponds to each melanopsin molecule’s activation generating a quantum of drive to the cascade. This formalism accurately captures the large initial peak and subsequent sustained steady state seen in both ipRGCs (Figs. 1C and 2) and circadian responses to light pulses (Kronauer et al. 1999).

The photocurrent induced by the cascade is transformed into a firing rate ν by the following filtering function, derived in the next section:

| (4) |

Derivation of the filtering function.

Because Eq. 3 describes the cascade-gated photocurrent but the data recorded are firing rates, low-amplitude photocurrents insufficient to evoke spikes will not be captured in the fits. Moreover, sufficiently large photocurrents could push the system into a state of depolarization block, causing firing to slow or stop (see below for further detail). To compensate for this, we use a filter function that suppresses firing rate at high photocurrents and at those currents too low to evoke spiking. Below a certain threshold photocurrent, the cell does not fire, which means that if we assume the cells in the population are instantaneously experiencing a photocurrent that is normally distributed, then some fraction of the cells at that moment will fail to have enough photocurrent to fire. Let y′ represent the amount of photocurrent and define p(y′) to be the distribution of cells experiencing photocurrent y′ so that

is the fraction of cells experiencing photocurrent in the range [y1, y2]. This will be a function of the mean μ of the normally distributed population, which we assume will be light dependent. If yT1 is the threshold that y must exceed for firing, then the fraction of cells firing is

and the average firing rate of these cells is

Assume that firing rate ν is proportional to photocurrent y′ above the threshold with constant of proportionality κ. The average firing rate of the cells that are firing is then the average photocurrent of those cells, scaled by κ, or

where σ is the standard deviation of the normally distributed population and y is the mean.

Whole cell recordings revealed that high-amplitude depolarization often blocked spiking activity in ipRGCs, especially M1 cells (Fig. 6A) (see also Hu et al. 2013 and Reifler et al. 2015). Because of such depolarization block, when the photocurrent exceeds a second threshold, yT2, the cell’s firing rate does not increase any further. In the model, this is captured by setting any currents above this threshold to yT2, to approximate the shape of the current-firing relationship previously observed for mouse ipRGCs (Hu et al. 2013).

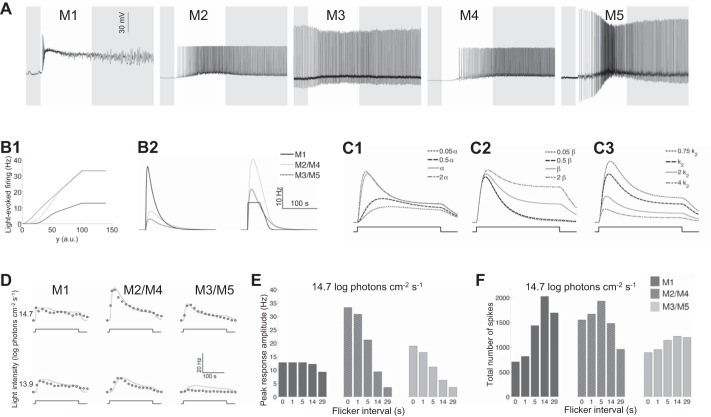

Fig. 6.

Mathematical modeling. A: typical whole cell-recorded light responses of the 5 types of rat ipRGCs. All stimuli were 10-s, full-field, 480-nm light steps with an intensity of 12.6 log photons cm−2·s−1 for the M1 and M2 cells and 13.6 log photons cm−2·s−1 for the M3–M5 cells. B: for all 3 cell clusters, firing rate filtering functions (B1) affect the impulse response functions (B2). The left plot in B2 shows the unfiltered impulse response y, corresponding to the scaled photocurrent. The right plot in B2 shows the filtered firing rate. C: varying α (C1), β (C2), and k2 (C3) about the mean values from the M2/M4 cluster changes the shape of the waveform y. Changing α shows how the model responds to changes in light intensity. Decreasing β reduces the steady-state spiking response while having little impact on peak firing rate, demonstrating how the rate of melanopsin reset changes the resulting waveform. Increasing k2 decreases both peak amplitude and steady-state response, making the waveform more closely resemble that of the M3/M5 cluster. D: fits (solid lines) of the model to the single-light-step experimental data (open circles). E and F: use of the model to reproduce the histograms from Fig. 5, A2 and B2, respectively, for the 3 ipRGC clusters.

The whole cell recordings in Fig. 6A were used to choose parameters for the filtering function across models. The upper threshold yT2 for all cell clusters was set sufficiently high so that only M1 cells entered depolarization block. The lower threshold yT1 was lowest for the M3/M5 cluster, matching the occasional spontaneous spiking seen in M3 cells (Fig. 6A). A larger value of σ, possibly implying a wider distribution of resting membrane potentials, was chosen for the M2/M4 cluster than for the others, in keeping with the somewhat larger error bars in the MEA data for that cluster (Fig. 2). Sample voltage thresholding functions for the ipRGC clusters are given in Fig. 6B1.

Parameter differences across cluster models.

The parameters k1, k2, and k4 were allowed to vary across the three ipRGC clusters, whereas the same values for α(I), β, and k3 were used for all clusters. Fixing α(I) and β across clusters establishes that these parameters are intrinsic to melanopsin, not ipRGC type. The choice of parameter k3 is arbitrary and was set to a fixed scalar across all clusters as a result. Parameter sets for each cluster are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter choices across the three ipRGC clusters’ models

| β | k1 | k2 | k4 | σ | yT1 | κ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 0.007 | 0.88 | 0.5 | 0.044 | 10 | 40 | 0.128 |

| M2/M4 | 0.007 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.027 | 17 | 40 | 0.333 |

| M3/M5 | 0.007 | 0.068 | 0.22 | 0.027 | 10 | 16 | 0.333 |

Values are parameter choices for 3 intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell (ipRGC) clusters’ (M1, M2/M4, and M3/M5) models. See text for parameter definitions.

The cascade scaling parameter k1 was greatest in the M1 cluster, reflecting the fact that M1 cells have the highest melanopsin density and largest photocurrents (Ecker et al. 2010). The cascade decay parameter k2 was also highest in the M1 cluster, which could suggest the fastest clearance of the cascade in M1 cells. The parameter k1 was roughly the same in both the M2/M4 and M3/M5 clusters. This choice, while initially surprising given the significant amplitude differences between the two clusters’ single-light-step responses (Fig. 2), was necessary to fit the cluster responses to the flickering flashes (Fig. 4), specifically, responses to the 29-s-interval flicker; if significant differences in k1 were assumed between the M2/M4 and M3/M5 clusters, the model would be unable to reproduce these clusters’ fairly similar amplitudes in their responses to this flicker. Instead, the M2/M4 vs. M3/M5 amplitude difference in their single-step responses (Fig. 2) results from a cascade clearance rate k2 in the M3/M5 cluster that is approximately double that in the M2/M4 cluster. This is the most marked difference between these two clusters’ models.

The firing scalar κ was chosen to be smaller for M1 than for the other clusters, approximating the current-firing differences previously observed across mouse ipRGC types (Hu et al. 2013). Furthermore, the value of σ in the filtering function was chosen to be highest in the M2/M4 cluster, possibly suggesting more variability in that population.

The effects on response waveform of varying α, β, and k2 are shown in Fig. 6C, whereas fits of the model to the single-light-step data for each cluster are provided in Fig. 6D. For all clusters, k3 was set at 250 and yT2 at 100. The light dependence of α was modeled as α(I) = α0I, with α0 = 3.7962 × 10−16 and where the units of I are photons cm−2·s−1. A derivation shows that the impulse response function for the model is given by

Sample plots of the impulse response function for the three models are shown in Fig. 6B2.

This simple model can reproduce a remarkable number of features observed in the experimental data. For instance, the characteristic shape of the response curve with an early peak followed by a lower steady state (Figs. 2 and 6D) results from the photic drive being proportional to α(1 − n). Moreover, terminating the light step when the firing rate is higher yields more poststimulus spikes than ending the light at a lower firing rate, because the signal decays exponentially in the absence of light (when α = 0). In addition, the relatively high sensitivity of M1 cells at low light levels (Fig. 3A1) is captured by the high value of k1, and the similarity between M1’s responses at 14.7 log and 13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1 is accounted for by depolarization block. In contrast, the M2/M4 and M3/M5 clusters have lower sensitivities than M1 cells and do not enter depolarization block. According to our models, the M2/M4 and M3/M5 clusters’ differences in single-light-step response amplitude are due to different cascade clearance rates (k2) rather than markedly different sensitivities to light (k1). Particularly interesting is that the models are able to approximately reproduce the results from the flickering-light experiment showing cluster differences in peak amplitude and total spike count (Fig. 6, E and F). As with the data (Fig. 5, A2 and B2), the M1 and M3/M5 models produce the most total spikes with 14 s of dark intervals, whereas the M2/M4 model produces the most total spikes at a 5-s interval (Fig. 6F).

By contrast, the model has difficulty matching the M3/M5 cluster’s flicker responses at 13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1 light, which we attribute to a particularly high percentage of cells in the population failing to respond at that intensity. The model is also unable to fully match the slow timescale of the M1 cluster’s firing rate decay after light offset (Fig. 6D); we hypothesize that this could be a consequence of only having one homogenous population of ion channels in the model, as opposed to two populations with slower and faster kinetics.

DISCUSSION

Nearly all previous MEA studies of photoresponse diversity grouped ipRGCs into two or three classes of unknown identities (Karnas et al. 2013; Neumann et al. 2008; Owens et al. 2012; Perez-Leighton et al. 2011; Tu et al. 2005, 2006), although a recent report associated the “type 1” cells present only in neonatal mice with the M4 type (Sexton et al. 2015). The present communication describes the first attempt to correlate MEA-recorded light responses with all five known morphological types of adult rodent ipRGCs, which exhibit three varieties of intrinsic light responses (Reifler et al. 2015). Since genetic fluorescent labeling of ipRGCs has been achieved only for mice (Do et al. 2009; Ecker et al. 2010; Schmidt et al. 2008) and retrograde labeling from the rat hypothalamus labels only M1 cells (Berson et al. 2002), the approach presented here is currently the only way to record from identified rat ipRGCs without resorting to low-throughput random screening (Reifler et al. 2015).

The single-light-step experiment confirmed several previously reported properties of ipRGCs. Specifically, M1 cells have the lowest threshold (Fig. 3A1) and the shortest latency to peak (Fig. 3B1), whereas M2/M4 cells generate the largest responses at high stimulus intensities (Fig. 3, A1 and C) (Reifler et al. 2015). Moreover, quantal efficiency usually declines as the duration of a light step increases (Fig. 3D), which can be attributed to light adaptation in which the gain of ipRGC phototransduction gradually decreases during continued illumination (Wong et al. 2005). A similar phenomenon was recently seen in “type 1” ipRGCs of the diurnal rodent Arvicanthis ansorgei, whose mean light-induced spike rate declined when stimulus duration was extended from 1 to 30 s (Karnas et al. 2013). Finally, quantal efficiency also tends to drop as light intensity increases (Fig. 3D), consistent with an earlier report that melanopsin’s flash response amplitude decreases progressively with increasing background light level (Do and Yau 2013).

Our data have also revealed new properties of ipRGCs. First, the above-mentioned adaptation to prolonged illumination suggests that a series of appropriately spaced short pulses might evoke more spikes than a single light step containing the same total number of photons, because the former induces less light adaptation within each pulse while permitting some degree of resensitization during the intervening dark periods (i.e., dark adaptation). This was clearly observed in the flicker experiment at 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1. As interpulse interval increased, the amount of light adaptation decreased whereas more dark adaptation was allowed. As a result, the responses to the light pulses became larger, until the interpulse interval reached an optimum, which was 14 s for both M1 and M3/M5 and 5 s for the M2/M4 cluster (Fig. 5B2). This observation may explain previous behavioral reports that discontinuous light is often more efficient than constant light for driving non-image-forming visual responses (Gooley et al. 2012; Gronfier et al. 2004; Lall et al. 2010; Rimmer et al. 2000; Vartanian et al. 2015; Zeitzer et al. 2011). However, when the interpulse interval increased beyond the optimum, the degree of response summation between pulses decreased. As a result, an interpulse interval of 29 s elicited fewer overall spikes than 5 or 14 s (Fig. 5B2).

Second, the flicker experiment shows that the integration time of melanopsin-based photoresponses may not be constant (Do et al. 2009), but rather depends on cell type as well as light intensity. At 13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1 (Fig. 5C1), M1 cells displayed substantial paired-pulse summation at the 1-s interpulse interval but little to no summation at any of the longer intervals tested. By contrast, M3/M5 cells’ responses continued to summate at the 5- and 14-s intervals, whereas M2/M4 responses summated at all intervals examined. Thus, at this light intensity, M2/M4 has the longest integration time, whereas M1 has the shortest. All clusters’ integration times increased at 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 (Fig. 5C2), because M1 cells’ 2nd peak-to-1st peak ratio stayed above 1 even at the 29-s interval, and the time constants of M2/M4’s and M3/M5’s exponential fits were higher than those at the lower intensity. Such dependence of integration time on intensity could explain why all ipRGCs’ peak photoresponse amplitude declined faster with increasing interval at 13.9 log (Fig. 5A1) than at 14.7 log photons cm−2·s−1 (Fig. 5A2).

Third, we found that all ipRGCs’ spiking could track the 5-s-interval (0.17 Hz) and lower frequency flickers, although no obvious tracking of the 1-s-interval (0.5 Hz) flicker was seen (Fig. 4). IpRGC responses to repetitive stimulation at different flicker frequencies had been investigated systematically only in A. ansorgei (Karnas et al. 2013). In that study, flickers between 0.02 and 20 Hz were presented. “Type 1” ipRGCs were found to track 0.1-Hz flickers but not 0.2-Hz or higher frequencies, whereas “type 2” cells showed no tracking at any of the frequencies studied (Karnas et al. 2013). Curiously, the pupillary light reflexes of rodless/coneless (i.e., melanopsin only) humans also appear unable to reliably track 0.05-Hz or higher frequency flickers (Gooley et al. 2012). These results raise the curious possibility that ipRGC phototransduction in nocturnal rodents has higher temporal sensitivity than that in diurnal species.

We also introduce a mathematical model for describing the dynamics of ipRGCs’ intrinsic photoresponse, and a number of empirically observed phenomena are captured by the structure of this model. Decreasing quantal efficiency over the course of a light step is a consequence of the photoresponse drive being proportional to α(1 − n), which maintains at a lower steady-state value after a transient period of high responsiveness. The slow timescale of dark adaptation is captured by our low β value. Depolarization block accounts for the relative similarities in the M1 cluster’s responses to 14.7 log and 13.9 log photons cm−2·s−1 light steps.

Furthermore, the parameters needed to fit the three clusters to the data characterize important similarities and distinctions between the ipRGC clusters. For all three models, α(I) and β were chosen to be the same, because these parameters reflect properties inherent to melanopsin. Specifically, α is the rate at which excitable melanopsin is activated, and β is the rate at which excited melanopsin is returned to the excitable state. Of these two parameters, only α was chosen to be light dependent. It is possible that if light is capable of both exciting and resetting melanopsin, then β should also be light dependent, with both a constant background component reflecting the resetting of melanopsin in the dark and a light-driven component that increases with increasing light. However, we found that making β light dependent does not significantly enhance our fits of MEA data, suggesting that light-driven resetting does not occur at the wavelength tested (480 nm) or that other protocols of photostimulation are needed to conclusively reveal photoreversal in ipRGCs (Rollag 2008).

Of the three clusters, M1 was the most distinct. Compared with the other two, it had the highest value of k1 by a large margin. This parameter reflects both the density of melanopsin and the amplification of the cascade triggered by melanopsin activation. M1 also was the cluster that required depolarization block to fit the firing rate, as reflected by much of the photic drive exceeding the upper firing threshold, yT2.

One of the most interesting results from the flicker experiment is that the M2/M4 cluster has approximately as many total spikes as the M3/M5 cluster at the 29-s darkness interval despite having many more spikes at the shorter intervals. To fit this result, the k1 parameters for both models were chosen to be roughly equivalent. Furthermore, the two models’ decay rates in darkness were very similar, and as such the k4 parameters were chosen to be the same for both clusters.

Although many parameters are set to be the same in both the M2/M4 and M3/M5 models, the most important difference between the two is the rate of decay of the cascade, k2. In the M2/M4 cluster, this rate is approximately half the value of the M3/M5 cluster. This single parameter is able to explain the differences in peak firing rate between the two clusters. One model prediction, therefore, is that faster cascade clearance in M3/M5 cells, and not significantly less overall excitation, explains the differences between their single-light-step response and that of M2/M4 cells.

To fit the firing rate data, electrophysiology had to be considered in addition to the phototransduction cascade. The relationship between current and firing rate was captured in the filtering function. Although this was essential for capturing the reduction in spiking due to depolarization block in the M1 cluster, future work should incorporate more detailed models of electrophysiology in place of this function to better capture the dynamics of spike generation.

Future modeling should also reevaluate the timescales of photocurrent activation and inactivation. Our model includes only a single equation for photocurrent induction; however, this assumption impeded our ability to fit the poststimulus firing rate decay seen in the M1 cluster (Fig. 6D). We hypothesize that there could be independent fast and slow ion channels underlying M1 cells’ photoresponses, which could explain their rapid onset and slow offset. At present, the channels responsible for ipRGC phototransduction are believed to be TRPC6 and TRPC7 (Xue et al. 2011). As more evidence emerges for the precise roles of these channels, the model can be updated accordingly.

The different electrophysiological behaviors of the ipRGC clusters are likely “tuned” in some sense to their different functional roles. By pairing these models with models of higher order neurons, we can begin to better understand how ipRGCs’ form and function align in the brain. Of particular interest is the M1 model, because no models of the mammalian circadian clock presently incorporate ipRGCs. The model developed in this work can be readily linked to a model of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons and can provide a more realistic photic drive to the central circadian pacemaker.

Finally, the mathematical models introduced in this article can be used to predict responses to arbitrary light waveforms. The remarkably different responses of the three ipRGC clusters to different presentations of light suggest that optimal lighting strategies should be tailored to the type of ipRGC being targeted. The use of mathematical models can illuminate the optimal strategies for exciting these cells for therapeutic purposes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Army Research Laboratory Biomathematics Program Grant W911NF-13-1-0449, a Research to Prevent Blindness Scientific Career Development Award, National Science Foundation Graduate Student Research Fellowship DGE 1256260, and National Eye Institute Grants P30 EY007003 and R01 EY023660.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

O.J.W., D.B.F., and K.Y.W. conception and design of research; O.J.W., L.S.Z., and K.Y.W. analyzed data; O.J.W., D.B.F., and K.Y.W. interpreted results of experiments; O.J.W. and K.Y.W. prepared figures; O.J.W. and K.Y.W. drafted manuscript; O.J.W., D.B.F., and K.Y.W. edited and revised manuscript; O.J.W., L.S.Z., A.N.R., M.E.D., D.B.F., and K.Y.W. approved final version of manuscript; L.S.Z., A.N.R., M.E.D., and K.Y.W. performed experiments.

REFERENCES

- Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science 295: 1070–1073, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TM, Tsujimura S, Allen AE, Wynne J, Bedford R, Vickery G, Vugler A, Lucas RJ. Melanopsin-based brightness discrimination in mice and humans. Curr Biol 22: 1134–1141, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SK, Badea TC, Hattar S. Photoentrainment and pupillary light reflex are mediated by distinct populations of ipRGCs. Nature 476: 92–95, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do MT, Kang SH, Xue T, Zhong H, Liao HW, Bergles DE, Yau KW. Photon capture and signalling by melanopsin retinal ganglion cells. Nature 457: 281–287, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do MT, Yau KW. Adaptation to steady light by intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 7470–7475, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker JL, Dumitrescu ON, Wong KY, Alam NM, Chen SK, LeGates T, Renna JM, Prusky GT, Berson DM, Hattar S. Melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion-cell photoreceptors: cellular diversity and role in pattern vision. Neuron 67: 49–60, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez ME, Fogerson PM, Ilardi MC, Borghuis BG, Chan E, Weng S, Auferkorte ON, Demb JB, Berson DM. Form and function of the M4 cell, an intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell type contributing to geniculocortical vision. J Neurosci 32: 13608–13620, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman MS, Lucas RJ, Soni B, von Schantz M, Munoz M, David-Gray Z, Foster R. Regulation of mammalian circadian behavior by non-rod, non-cone, ocular photoreceptors. Science 284: 502–504, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley JJ, Ho Mien I, St Hilaire MA, Yeo SC, Chua EC, van Reen E, Hanley CJ, Hull JT, Czeisler CA, Lockley SW. Melanopsin and rod-cone photoreceptors play different roles in mediating pupillary light responses during exposure to continuous light in humans. J Neurosci 32: 14242–14253, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DM, Wong KY, Shapiro P, Frederick C, Pattabiraman K, Berson DM. Melanopsin ganglion cells use a membrane-associated rhabdomeric phototransduction cascade. J Neurophysiol 99: 2522–2532, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronfier C, Wright KP Jr, Kronauer RE, Jewett ME, Czeisler CA. Efficacy of a single sequence of intermittent bright light pulses for delaying circadian phase in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E174–E181, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattar S, Liao HW, Takao M, Berson DM, Yau KW. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science 295: 1065–1070, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Hill DD, Wong KY. Intrinsic physiological properties of the five types of mouse ganglion-cell photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol 109: 1876–1889, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnas D, Hicks D, Mordel J, Pevet P, Meissl H. Intrinsic photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the diurnal rodent, Arvicanthis ansorgei. PLoS One 8: e73343, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronauer RE, Forger DB, Jewett ME. Quantifying human circadian pacemaker response to brief, extended, and repeated light stimuli over the phototopic range. J Biol Rhythms 14: 500–515, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lall GS, Revell VL, Momiji H, Al Enezi J, Altimus CM, Guler AD, Aguilar C, Cameron MA, Allender S, Hankins MW, Lucas RJ. Distinct contributions of rod, cone, and melanopsin photoreceptors to encoding irradiance. Neuron 66: 417–428, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtin A, Milton JG. Modelling autonomous oscillations in the human pupil light reflex using non-linear delay-differential equations. Bull Math Biol 51: 605–624, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RJ, Douglas RH, Foster RG. Characterization of an ocular photopigment capable of driving pupillary constriction in mice. Nat Neurosci 4: 621–626, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RJ, Foster RG. Neither functional rod photoreceptors nor rod or cone outer segments are required for the photic inhibition of pineal melatonin. Endocrinology 140: 1520–1524, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister M, Pine J, Baylor DA. Multi-neuronal signals from the retina: acquisition and analysis. J Neurosci Methods 51: 95–106, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann T, Ziegler C, Blau A. Multielectrode array recordings reveal physiological diversity of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the chick embryo. Brain Res 1207: 120–127, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens L, Buhr E, Tu DC, Lamprecht TL, Lee J, Van Gelder RN. Effect of circadian clock gene mutations on nonvisual photoreception in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 454–460, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Leighton CE, Schmidt TM, Abramowitz J, Birnbaumer L, Kofuji P. Intrinsic phototransduction persists in melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells lacking diacylglycerol-sensitive TRPC subunits. Eur J Neurosci 33: 856–867, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencio I, Jiang G, De Grip WJ, Hayes WP, Rollag MD. Melanopsin: an opsin in melanophores, brain, and eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 340–345, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea MS, Figueiro MG, Bullough JD, Bierman A. A model of phototransduction by the human circadian system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 50: 213–228, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifler AN, Chervenak AP, Dolikian ME, Benenati BA, Meyers BS, Demertzis ZD, Lynch AM, Li BY, Wachter RD, Abufarha FS, Dulka EA, Pack W, Zhao X, Wong KY. The rat retina has five types of ganglion-cell photoreceptors. Exp Eye Res 130: 17–28, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer DW, Boivin DB, Shanahan TL, Kronauer RE, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Dynamic resetting of the human circadian pacemaker by intermittent bright light. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R1574–R1579, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollag MD. Does melanopsin bistability have physiological consequences? J Biol Rhythms 23: 396–399, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TM, Alam NM, Chen S, Kofuji P, Li W, Prusky GT, Hattar S. A role for melanopsin in alpha retinal ganglion cells and contrast detection. Neuron 82: 781–788, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TM, Kofuji P. Functional and morphological differences among intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci 29: 476–482, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TM, Kofuji P. Structure and function of bistratified intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. J Comp Neurol 519: 1492–1504, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TM, Taniguchi K, Kofuji P. Intrinsic and extrinsic light responses in melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells during mouse development. J Neurophysiol 100: 371–384, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton TJ, Bleckert A, Turner MH, Van Gelder RN. Type I intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells of early post-natal development correspond to the M4 subtype. Neural Dev 10: 17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu DC, Owens LA, Anderson L, Golczak M, Doyle SE, McCall M, Menaker M, Palczewski K, Van Gelder RN. Inner retinal photoreception independent of the visual retinoid cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10426–10431, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu DC, Zhang D, Demas J, Slutsky EB, Provencio I, Holy TE, Van Gelder RN. Physiologic diversity and development of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Neuron 48: 987–999, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian GV, Zhao X, Wong KY. Using flickering light to enhance nonimage-forming visual stimulation in humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56: 4680–4688, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viney TJ, Balint K, Hillier D, Siegert S, Boldogkoi Z, Enquist LW, Meister M, Cepko CL, Roska B. Local retinal circuits of melanopsin-containing ganglion cells identified by transsynaptic viral tracing. Curr Biol 17: 981–988, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KY, Dunn FA, Berson DM. Photoreceptor adaptation in intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Neuron 48: 1001–1010, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KY, Dunn FA, Graham DM, Berson DM. Synaptic influences on rat ganglion-cell photoreceptors. J Physiol 582: 279–296, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Do MT, Riccio A, Jiang Z, Hsieh J, Wang HC, Merbs SL, Welsbie DS, Yoshioka T, Weissgerber P, Stolz S, Flockerzi V, Freichel M, Simon MI, Clapham DE, Yau KW. Melanopsin signalling in mammalian iris and retina. Nature 479: 67–73, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi FH, Hull JT, Peirson SN, Wulff K, Aeschbach D, Gooley JJ, Brainard GC, Gregory-Evans K, Rizzo JF 3rd, Czeisler CA, Foster RG, Moseley MJ, Lockley SW. Short-wavelength light sensitivity of circadian, pupillary, and visual awareness in humans lacking an outer retina. Curr Biol 17: 2122–2128, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitzer JM, Ruby NF, Fisicaro RA, Heller HC. Response of the human circadian system to millisecond flashes of light. PLoS One 6: e22078, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Stafford BK, Godin AL, King WM, Wong KY. Photoresponse diversity among the five types of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol 592: 1619–1636, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]