Abstract

Neurons in the silkmoth antennal lobe (AL) are well characterized in terms of their morphology and odor-evoked firing activity. However, their intrinsic electrical properties including voltage-gated ionic currents and synaptic connectivity remain unclear. To address this, whole cell current- and voltage-clamp recordings were made from second-order projection neurons (PNs) and two morphological types of local interneurons (LNs) in the silkmoth AL. The two morphological types of LNs exhibited distinct physiological properties. One morphological type of LN showed a spiking response with a voltage-gated sodium channel gene expression, whereas the other type of LN was nonspiking without a voltage-gated sodium channel gene expression. Voltage-clamp experiments also revealed that both of two types of LNs as well as PNs possessed two types of voltage-gated potassium channels and calcium channels. In dual whole cell recordings of spiking LNs and PNs, activation of the PN elicited depolarization responses in the paired spiking LN, whereas activation of the spiking LN induced no substantial responses in the paired PN. However, simultaneous recording of a nonspiking LN and a PN showed that activation of the nonspiking LN induced hyperpolarization responses in the PN. We also observed bidirectional synaptic transmission via both chemical and electrical coupling in the pairs of spiking LNs. Thus our results indicate that there were two distinct types of LNs in the silkmoth AL, and their functional connectivity to PNs was substantially different. We propose distinct functional roles for these two different types of LNs in shaping odor-evoked firing activity in PNs.

Keywords: insect brain, antennal lobe, patch-clamp recording

brain microcircuits comprise a heterogeneous population of neurons with various types of synaptic connectivity. The antennal lobe (AL), which is the analog of the vertebrate olfactory bulb, is a first-order olfactory microcircuit that shapes odor representation (Hildebrand and Shepherd 1997). Odor molecules are detected by olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) expressing a particular receptor gene, and the axons of ORNs that converge onto a single glomerulus send specific olfactory information to second-order projection neurons (PNs) in the AL (Wilson and Mainen 2006). The AL comprises multiple units of neuropil called glomeruli, to which the ORNs extend synaptic terminals (Hildebrand and Shepherd 1997). In the moth AL, there is a large and sexually dimorphic structure called the macroglomerular complex (MGC) (Hansson and Anton 2000). The AL also contains many local interneurons (LNs) that are organized into complicated synapses with ORNs and PNs (Christensen et al. 1993). LNs, which are thought to be mostly GABAergic (Christensen et al. 1998a; Hoskins et al. 1986; Malun 1991; Seki and Kanzaki 2008; Wilson and Laurent 2005), are a primary source of the inhibitory postsynaptic potentials observed in PNs (Christensen et al. 1993). GABAergic inhibitory input from LNs in the AL is strongly suggested to play an important role in shaping PN responses, regardless of insect species (Christensen et al. 1998b; MacLeod and Laurent 1996; Olsen and Wilson 2008; Sachse and Galizia 2002; Stopfer et al. 1997; Tabuchi et al. 2013; Watanabe et al. 2012; Wehr and Laurent 1999; Wilson and Laurent 2005).

In recent years, however, immunohistochemical analysis of the AL in various insect species has revealed various non-GABA neurotransmitter molecules in LNs, such as acetylcholine, glutamate, and neuropeptides (Berg et al. 2009; Carlsson et al. 2010; Iwano and Kanzaki 2005; Liu and Wilson 2013; Shang et al. 2007). Not only immunohistochemical analysis but also electrophysiological analysis have revealed non-GABAergic neurotransmission such as cholinergic excitation and electrical synaptic connection (Huang et al. 2010; Yaksi and Wilson 2010) and glutaminergic inhibition of LNs in the Drosophila AL (Liu and Wilson 2013).

In addition to the diversity in neurotransmitter release, heterogeneous morphologies and spiking patterns of LNs have also been comprehensively characterized (Chou et al. 2010; Reisenman et al. 2011; Seki et al. 2010), suggesting that LNs are not quite as simple as previously thought. In addition to spiking types of LNs, nonspiking types have been identified in the locust (Laurent and Davidowitz 1994) and the cockroach Periplaneta americana (Husch et al. 2009a) as hemimetabolous insects, as well as in the noctuid moth Agrotis ipsilon as a holometabolous insect (Lavialle-Defaix et al. 2015). Heterogeneity of voltage-gated calcium currents in spiking and nonspiking LNs were described in the P. americana AL, suggesting parallel signal propagation pathways with different temporal dynamics between spiking and nonspiking LNs (Husch et al. 2009a). Following that study, nonspiking LNs were further classified with distinct morphologies and membrane properties (Husch et al. 2009b). Moreover, heterogeneous immunoreactivities correlating with their morphological and physiological differences have been shown (Fusca et al. 2013). In terms of functional connectivity, reciprocal chemical inhibition among spiking LNs has been identified (Warren and Kloppenburg 2014) in the P. americana AL, but the functional connectivity of nonspiking LNs remains unclear.

The aim of this study is to characterize intrinsic membrane properties and functional connectivity of LNs in the silkmoth (Bombyx mori) AL. Our previous studies have shown that GABAergic mechanisms suppress PN responses only in the presence of strong ORN inputs, indicating that activation of LNs occurs in a stimulus-dependent fashion in the silkmoth AL (Fujiwara et al. 2014; Tabuchi et al. 2013). In the present work, we examined the detailed biophysical properties of individual AL neurons to better understand the inhibitory mechanism. In addition to the conventional spiking type of LNs, we found a specific morphological type of LN that has nonspiking-type physiological properties without gene expression of a voltage-gated sodium channel. We also investigated functional synaptic connectivity by dual whole cell recording and found that the postsynaptic change of PN membrane potential in response to activation of the nonspiking LNs was substantially different from activation of the spiking LNs. Thus our results show that nonspiking and spiking LNs in the silkmoth AL are distinguished by morphology, intrinsic membrane properties, and even functional connectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The w1-pnd strain (nondiapausing line, colorless eggs and eyes) of male silkmoth was used. Larvae were reared on an artificial diet (Silk Mate 2S; Nosan Bio Department, Yokohama, Japan) at 26°C and 60% relative humidity under a 16:8-h light-dark cycle. Animals were used within 2–8 days after eclosion.

Preparation.

Male silkmoth was chilled on ice (30 min) for anesthesia and immobilized on a dissecting chamber following isolation of the head. During the dissection, silkmoth physiological saline solution [140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 7 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM trehalose, 5 mM N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (TES), and 50 mM sucrose; pH 7.0] was continuously perfused over the preparation. Saline was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 before use. The brain was exposed by opening the head capsule. The large tracheae and the intracranial muscles were removed. To better visualize the recording site and to facilitate efficient penetration of pharmacological chemicals, the AL was isolated surgically by removing the rest of the brain and glial sheath that envelops the AL. We note that antenna remains intact in this preparation during single-electrode recording. However, we performed dual-electrode recording under the condition in which the antenna was removed to eliminate the afferent ORN inputs, which generate fluctuations of membrane potential and thus may interfere with detection of the postsynaptic response (Kazama and Wilson 2009). The surface of the cell body was briefly treated with enzymes (0.5 mg/ml collagenase, type 4; Worthington Biochemical; 2 mg/ml dispase, grade II; Roche) at 25°C for 5 min and cleaned with a small stream of saline that was pressure-ejected from a large-diameter pipette. The cell surface was further cleaned by positive pressure from the recording electrode before recording. The preparation was immobilized on the bottom of a 35 × 10-mm dish chamber using a plastic anchor and wax. The chamber was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Diaphoto 300; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and viewed with phase contrast optics and a ×40 objective lens. To exchange the bath solution, the preparation was perfused with saline by means of a gravity-driven system.

Patch-clamp recordings.

Whole cell recordings were performed at room temperature (25°C). Patch pipettes (5–8 MΩ) were fashioned from borosilicate glass capillaries with a Flaming/Brown puller (P-97; Sutter Instrument). The internal solution (150 mM K-gluconate, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM TES, 4 mM Na2-ATP, 0.5 mM GTP, 2 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, and 20 mM sucrose; pH 7.0) was used for whole cell recording unless otherwise indicated. Biocytin hydrazide (13 mM; Life Technologies) was added to the pipette solution before the recording. The purpose of the post hoc staining was to observe the morphological features of the recorded cell. Detailed procedures for single-cell labeling are described later. Recordings were acquired with an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon Instruments) and sampled with a Digidata 1200 interface. Dual whole cell recordings from pairs of AL neurons were made with two Axopatch 1D amplifiers. These devices were controlled on a computer using pCLAMP software. The signals were sampled at 20 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz. Junction potentials of 17 mV were nullified prior to high-resistance gigaohm seal formation. Series resistance was compensated by 60% except for recordings of small-amplitude currents, for which it was not compensated. Linear leakage currents were subtracted from all records by using pCLAMP software.

Single-cell labeling.

After whole cell recording, the AL was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h at 4°C. After being washed for 1 h in several changes of 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, single neurons stained with biocytin were visualized by incubation with Alexa 488-conjugated streptavidin (Life Technologies) diluted 1:100 for 24 h on a shaker at 4°C. The AL was then dehydrated with a concentration gradient of ethanol from 70% to 100%, and cleared in methyl salicylate. Morphology of the targeted neuron was imaged using a confocal imaging system (LSM-510; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with 488-nm excitation and a bandpass filter (505–550 nm). Serial optical sections were acquired at 0.7- to 1.0-μm intervals at a size of 512 × 512 pixels, and obtained images were adjusted for contrast and brightness using Adobe Photoshop CS (San Jose, CA) or LSM Image Browser rel. 4.2 software (Carl Zeiss).

Single-cell RT-PCR.

After electrophysiological recording with the whole cell patch configuration, suction was applied to draw the cytoplasm slowly into the tip of the pipette. The pipette was immediately transferred to an RNase-free 0.2-ml PCR tube containing 10 μl of RNase-free PBS solution with 1–2 U/μl RNasin RNase inhibitor, 0.002 U/μl RQ1 RNase-free DNase, and 1 μM dithiothreitol (Promega). cDNA was synthesized from the total RNA using an oligo-dT adaptor primer and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase supplied with the CellAmp Whole Transcriptome Amplification Kit ver2 (no. 3734; Takara, Shiga, Japan). The cDNA was amplified using Ex Taq DNA polymerase (RR006A; Takara) under the following thermal program: 94°C for 2 min, and 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, followed by one cycle at 72°C for 5 min. For amplification of BmNaV, a silkmoth voltage-gated sodium channel gene (Shao et al. 2009), primers used were 5′-ACATTCGGCATAGAAGCAA-3′ and 5′-TCGTGTCTTGATCAGCTG-3′, which can amplify the region containing exons 19a/b (Shao et al. 2009). This region corresponds to a highly conserved transmembrane domain, and no splicing form without the exons was detected in the adult silkmoth (Shao et al. 2009). For amplification of silkmoth ribosomal protein 49 (Bmrp49) as a positive control (Shinoda and Itoyama 2003), 5′-CAGGCGGTTCAAGGGTCAATAC-3′ and 5′-TGCTGGGCTCTTTCCACGA-3′ were used. Equal amounts of PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel. The identities of the PCR products were verified by DNA sequence analysis on an ABI 310 genetic analyzer using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit with the AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS (Applied Biosystems).

Pharmacological treatment.

Ionic currents were isolated with a combination of pharmacological blockers, appropriate voltage protocols, and ion substitution. Sodium currents (INa) were blocked by tetrodotoxin (TTX; 10−7 M). Calcium currents (ICa) were blocked by Cd2+ (10−4 M). 4-Aminopyridine (4-AP; 5 × 10−3 M) was used to block transient K+ currents (Itransient), and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA; 2 × 10−2 M) was used to block other sustained K+ currents (Isustained). In addition, blockade of both K+ currents was achieved by replacing K-gluconate in the patch-pipette with Cs-gluconate. The electrical synapse recordings were made in the presence of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+. To offset the change in osmolarity due to additional agents, the sucrose concentration in the silkmoth physiological saline solution described above was modified as needed. Equilibrium potentials (for 25°C) were calculated using the Nernst equation, assuming that the intracellular ion concentration equaled the concentration of the patch pipette internal solution. To measure steady-state activation, incrementing voltage step pulses were applied from a constant holding potential. The voltage dependence of voltage-gated K+ currents was determined by converting the peak current to peak conductance (G). These currents were scaled as fractions of the calculated maximal conductance. The voltage dependence of activation for ICa was determined from tail currents. The resulting current-voltage (I-V) curves were fitted to a first-order Boltzmann equation of the form

| (1) |

where A is the amplitude of the conductance (or tail current) and s is the slope factor. V0.5 is the voltage of half-maximal activation (V0.5act). Steady-state inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium currents was measured from a constant holding potential. Incrementing pre-steps were followed by a constant test pulse, for which the peak currents were measured. The data, scaled as a fraction of the maximal current (ICa, INa), were fit to a first-order Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1), where V0.5 is the voltage for half-maximal inactivation (V0.5act).

Data analysis.

All analysis, statistical evaluation, and graphing were performed using Igor software (WaveMetrics) and MATLAB (The MathWorks). Chemical postsynaptic responses from dual whole cell recordings were averaged across three trials. The change in chemical postsynaptic membrane potential was calculated by subtracting the mean membrane potential in the postsynaptic cell during 1.2 s before current injection in the presynaptic cell from the mean membrane potential during the 300-ms period of current injection in the presynaptic cell. We modulated the amount of injected current in every experiment so that we could induce a substantial number of action potential (for spiking LN and PN) or a substantial amount of depolarization that reaches overshoot level (for nonspiking LN). Electrical coupling recordings were averaged across 30 trials, and the coupling coefficient between 2 cells was determined by the ratio of the voltage response in the postsynaptic cell divided by the voltage response in the presynaptic cell under steady-state conditions. All values are means ± SE averaged across experiments; the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparisons of two groups, and ANOVAs followed by post hoc multiple t-tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction were performed for multiple comparisons. A significance level of 0.05 was accepted for all testing.

RESULTS

Whole cell recordings were performed from cell bodies located in the medial and/or lateral cell cluster of the isolated AL preparation, and the morphology of the recorded neurons was visualized post hoc using confocal imaging. PN data were obtained from medial cell cluster recordings, whereas LN data were obtained from lateral cell cluster recordings. The morphological classification of LNs was based on the criteria from a previous study (Seki and Kanzaki 2008). In that study, two global multiglomerular types of LNs that arborized in both the MGC and most ordinary glomeruli were identified. These LNs were named “MGC-allGs-sparse” or “MGC-allGs-dense” with respect to the difference in dendritic density (Seki and Kanzaki 2008). Mapping cell body position of the LNs revealed that cell bodies of the MGC-allGs-sparse LNs, which is the most common population, were widely distributed in the lateral cell cluster, whereas those of the MGC-allGs-dense LNs resided more ventrally and deeply (Seki and Kanzaki 2008). The different locations of cell bodies allowed us to investigate these two morphologically distinct types of LNs preferentially by selecting them on the basis of soma position, and therefore we focused on examining these two types of LNs in our study. Despite our selection strategy, we also obtained a small percentage of other morphological types of cells, but they were excluded from the study.

Distinct physiological properties of the two morphologically distinct LNs.

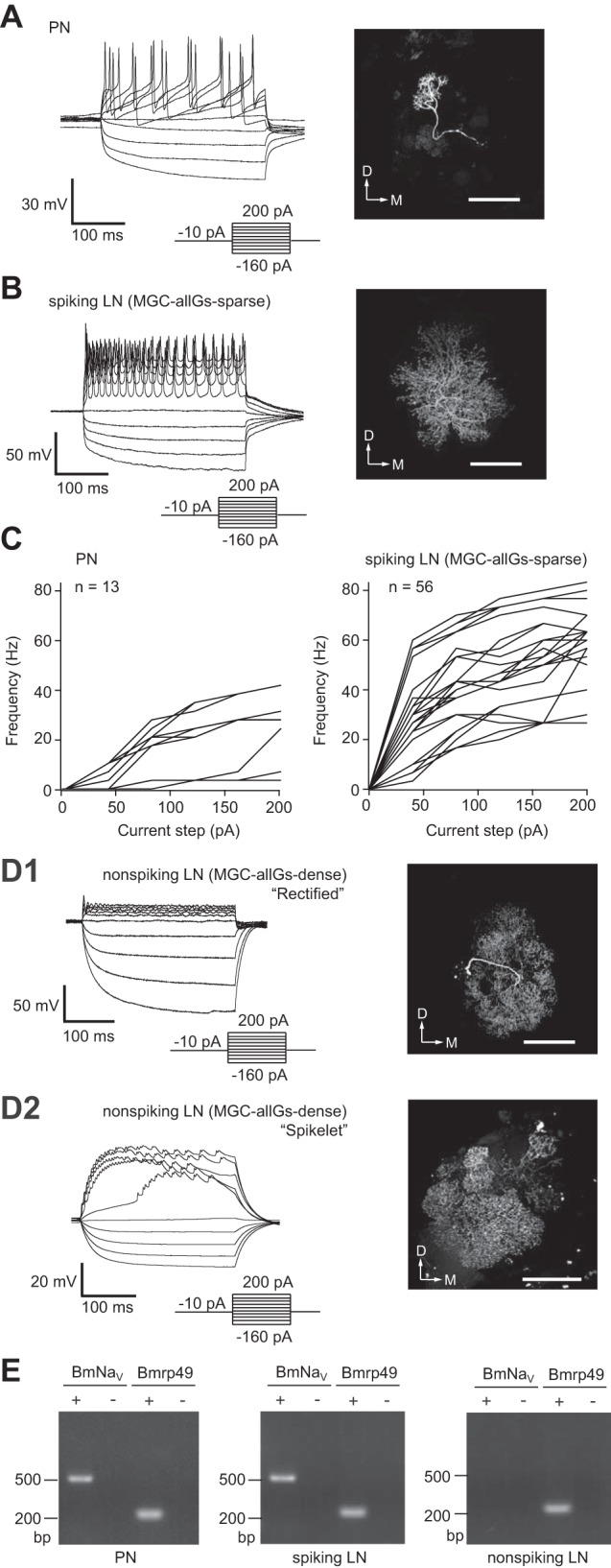

We first characterized the physiological profiles of AL neurons in current-clamp mode. In response to depolarized current injection, all PNs and MGC-allGs-sparse LNs showed spiking responses with TTX sensitivity (Fig. 1, A and B). The firing pattern of both PNs and MGC-allGs-sparse LNs showed diversity in terms of mean frequency (Fig. 1C). Threshold membrane potential of the action potential was −36.3 ± 4.7 mV in PNs and −35.6 ± 4.8 mV in MGC-allGs-sparse LNs, and the spike half-widths were 1.96 ± 0.06 ms in PNs and 1.98 ± 0.1 ms in MGC-allGs-sparse LNs. PNs had an average resting membrane potential of −62.4 ± 2.9 mV, an input resistance of 217.4 ± 117.4 MΩ, and membrane capacitance of 7.8 ± 1.1 pF. MGC-allGs-sparse LNs had an average resting membrane potential of −53.3 ± 2.7 mV, an input resistance of 155.7 ± 64.7 MΩ, and membrane capacitance of 8.2 ± 0.6 pF (summarized in Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Distinct physiological properties with two morphologically distinct local interneurons (LNs) and projection neuron (PN). A: whole cell current-clamp recordings of PNs showing their typical membrane voltage responses to current steps (left) and the morphology of a recorded neuron, which is visualized by filling with biocytin (right). D, dorsal; M, medial. Scale bar, 100 μm. B: whole cell current-clamp recordings of spiking LNs showing their typical membrane voltage responses to current steps (left) with MGC-allGs-sparse morphology (global multiglomerular type of LN that arborizes in both the MGC and most ordinary glomeruli; see text), which is visualized by filling with biocytin (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. C: mean firing rate vs. injected current for PNs (left) and for spiking LNs (right). The mean firing frequency of action potentials during the current injection was calculated (n = 13 for PNs; n = 56 for LNs). D: whole cell current-clamp recordings of nonspiking LNs and their MGC-allGs-dense morphology, which is visualized by filling with biocytin. D1: “rectified” response of nonspiking LNs showing strong rectification in response to a depolarizing current injection (left) and the MGC-allGs-dense morphology of the recorded neuron (right). D2: “spikelet” response of nonspiking LNs showing a tetrodotoxin (TTX)-insensitive mini-spike waveform in response to a depolarizing current injection (left) and the MGC-allGs-dense morphology of the recorded neuron (right). Scale bars, 100 μm. E: single-cell RT-PCR analysis of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene (BmNaV). Single-cell RT-PCR was conducted with total RNA from PNs and spiking and nonspiking LNs. The minus sign indicates a negative control without reverse transcriptase. The ribosomal protein gene (Bmrp49) was used as a positive control.

Table 1.

Summary of electrophysiological parameters

| Parameter | PNs | Spiking LNs (MGC-allGs-sparse) | Nonspiking LNs (MGC-allGs-dense) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting membrane potential, mV | −62.4 ± 2.9 | −53.3 ± 2.7 | −49.7 ± 6.4 |

| Input resistance, MΩ | 217.4 ± 117.4 | 155.7 ± 64.7 | 48.4 ± 3.6 |

| Membrane capacitance, pF | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 8.2 ± 0.6 | 27.9 ± 3.4 |

| Spike threshold, mV | −36.3 ± 4.7 | −35.6 ± 4.8 | n/a |

| Spike half-width, ms | 1.96 ± 0.06 | 1.98 ± 0.1 | n/a |

Values are means ± SE of electrophysiological parameters of projection neurons (PNs; n = 13), spiking local interneurons (LNs) that were confirmed as macroglomerular complex and most glomeruli (MGC-allGs)-sparse morphological type (n = 56), and nonspiking LNs that were confirmed as MGC-allGs-dense morphological type (n = 17). PNs analyzed in the study were of both uniglomerular (11 of 13) and multiglomerular (2 of 13) morphological type. n/a, Not applicable.

In contrast to PNs and MGC-allGs-sparse LNs, we found that none of the MGC-allGs-dense LNs showed TTX-sensitive action potential in response to a depolarizing current pulse (Fig. 1D). The responses of MGC-allGs-dense LNs were classified into “rectified” and “spikelet” types. The rectified response showed strong rectification following injection of depolarizing current (Fig. 1D1). The spikelet response showed small membrane potential changes with a spike-like waveform, but they were not Na+ action potentials because of their small amplitude (<3 mV) and TTX insensitivity (Fig. 1D2). These nonspiking LNs with MGC-allGs-dense morphology had an average resting membrane potential of −49.7 ± 6.4 mV, an input resistance of 48.4 ± 3.6 MΩ, and membrane capacitance of 27.9 ± 3.4 pF (summarized in Table 1).

To examine whether the difference in firing properties was due to the expression of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene, we collected cytoplasm from the recorded cells following the electrophysiological recording and performed single-cell RT-PCR. Using single-cell RT-PCR with PCR primers that amplify the silkmoth voltage-gated sodium channel gene (BmNaV) (Shao et al. 2009), we found that BmNaV was not detectable in MGC-allGs-dense LNs but was present in PNs and MGC-allGs-sparse LNs (Fig. 1E).

In summary, our results demonstrate that PNs and MGC-allGs-sparse LNs generated a spiking response with BmNaV expression, whereas MGC-allGs-dense LNs showed a nonspiking response without BmNaV expression. Hereafter, for simplicity, we refer to spiking LNs with MGC-allGs-sparse morphology as “spiking LNs” and nonspiking LNs with MGC-allGs-dense morphology as “nonspiking LNs.”

Comparison of potassium and sodium currents in individual AL neurons.

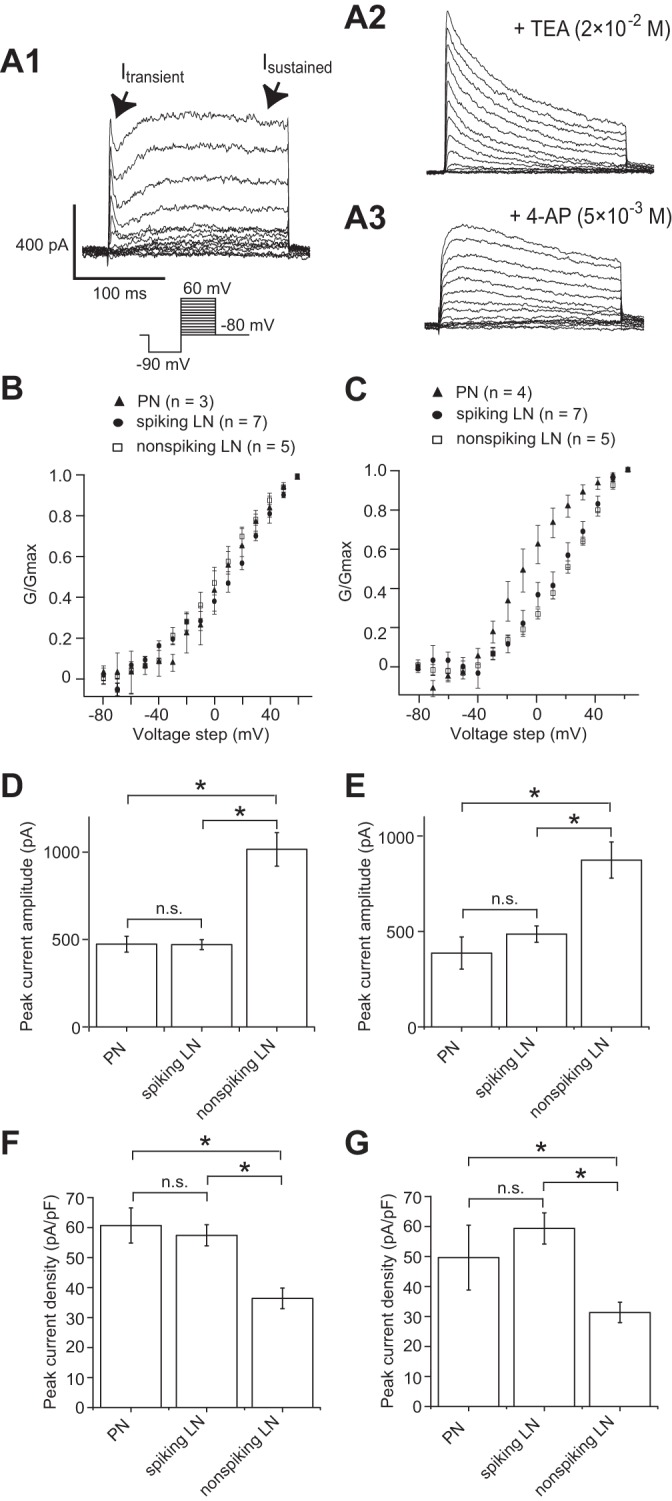

To compare voltage-dependent outward currents between AL neurons, we conducted pharmacological treatment with 10−7 M TTX and 10−4 M Cd2+. At least two outward currents were identified in all types of AL neurons. The two currents had different temporal kinetics (transient and sustained current) and pharmacological sensitivity to standard K+ current blockers, namely, 4-AP and TEA (Fig. 2A). The transient outward current was sensitive to 4-AP, and the sustained outward current was sensitive to TEA (Fig. 2A). To isolate the 4-AP-sensitive component of the transient outward current (Itransient), the preparation was bathed with saline containing 10−7 M TTX, 10−3 M CdCl2, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. The targeted neuron was held at −80 mV in the whole cell configuration. To examine the voltage dependence of the current, voltage step pulses were added in 10-mV increments between −80 and 60 mV. A hyperpolarizing prepulse was applied to −90 mV to exclude inactivation of ionic currents. Itransient displayed rapid inactivation following the transient activation during a maintained depolarization (Fig. 2A2). The peak currents evoked by each voltage pulse were used to construct the conductance-voltage (G-V) relationship (assuming EK = −98.5 mV). Quantitative analysis revealed that the voltage dependence of activation as measured by the G-V relationship was similar between AL neurons (Fig. 2B). We also examined the TEA-sensitive component of the sustained outward current (Isustained). To record Isustained, the preparation was bathed with saline containing 10−7 M TTX, 10−3 M CdCl2, and 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP. Isustained was activated with voltage step pulses above −30 mV, and the profile of the current was sustained. Isustained showed little inactivation, and subsequently there was no detectable voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation (Fig. 2A3). The peak currents evoked by each voltage pulse were used to construct the G-V relationship (assuming EK = −98.5 mV). Similar to the result of Itransient, both spiking and nonspiking LNs showed similar G-V relationships of Isustained (Fig. 2C). We also compared the maximum current amplitude of Itransient and Isustained in AL neurons. The results show that both of the current amplitudes of Itransient and Isustained were significantly greater by ∼1.9-fold in nonspiking LNs compared with spiking LNs and PNs (Fig. 2, D and E). On the other hand, since nonspiking LNs were electrotonically more extensive than spiking LNs and PNs (Table 1), these current densities were significantly reduced in nonspiking LNs compared with spiking LNs and PNs (Fig. 2, F and G).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of transient and sustained K+ currents (Itransient and Isustained) in individual antennal lobe (AL) neurons in whole cell voltage-clamp configuration. The conductance (G) is determined by assuming EK = −98.5 mV. A: Itransient and Isustained. A1: current traces showing voltage-dependent activation of Itransient and Isustained, which were measured during the step depolarization in cells loaded with a K-gluconate patch pipette internal solution and bathed in a solution containing 10−7 M TTX and 10−3 M CdCl2. A2: current traces showing the pharmacologically isolated Itransient with additional application of 2 × 10−2 M tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA). A3: current traces showing the pharmacologically isolated Isustained with additional application of 5 × 10−3 M 4-aminopyridine (4-AP). Traces in A1, A2, and A3 were obtained from different cells. B: conductance-voltage (G-V) relationship of Itransient. C: G-V relationship of Isustained. D: comparison of absolute maximum current amplitude of Itransient. E: comparison of absolute maximum current amplitude of Isustained. F: comparison of peak current density of Itransient. G: comparison of peak current density of Isustained. *P < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

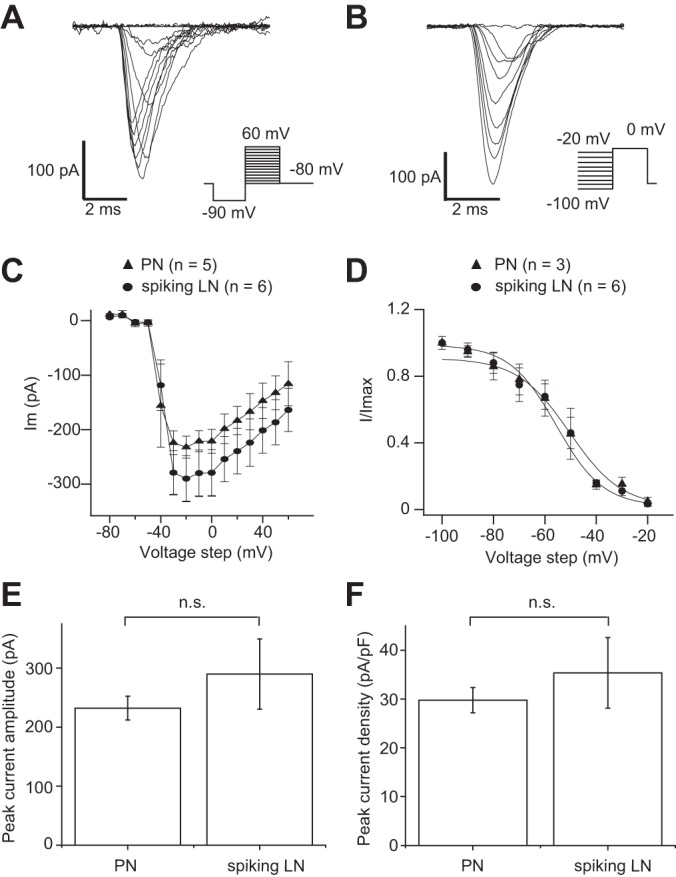

Next, to compare voltage-dependent sodium currents in spiking LNs and PNs, outward currents were blocked by substituting K-gluconate with Cs-gluconate in the patch pipette solution and by adding 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. To isolate INa in spiking LNs and PNs, the saline was exchanged for a solution containing 10−3 M CdCl2, 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. INa was activated and inactivated very rapidly (Fig. 3A). The I-V relationship of the peak INa was determined by voltage steps between −80 and 60 mV in 10-mV increments (Fig. 3C). The currents in both spiking LNs and PNs were activated at potentials higher than −50 mV, and maximum current was seen at approximately −20 mV (Fig. 3C). To measure steady-state inactivation, 500-ms prepulses were delivered in 10-mV increments from −100 to −20 mV, followed by a test pulse to 20 mV (Fig. 3B). The I-V curves were then fit to a first-order Boltzmann equation in both spiking LNs and PNs (Fig. 3D). No significant difference was found between INa of spiking LNs and PNs in terms of their peak current amplitude (Fig. 3E) as well as current density (Fig. 3F). These results together suggested that the electrophysiological properties of INa were similar in spiking LNs and PNs.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Na+ currents (INa) in PNs and spiking LNs in whole cell voltage-clamp configuration. A: current traces showing voltage-dependent activation of INa, measured during the step depolarization in cells loaded with a CsCl patch pipette internal solution and bathed in a solution containing 10−3 M CdCl2, 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. The representative traces shown are from spiking LNs. B: current traces showing voltage-dependent inactivation of INa, measured during the constant test pulse of 0 mV before the step depolarization in cells loaded with a CsCl patch pipette internal solution and bathed in a solution containing 10−3 M CdCl2, 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. The representative traces shown are from spiking LNs. C: I-V relationship of voltage-dependent activation of INa. D: I-V relationship of voltage-dependent inactivation of INa. The curves in C and D were fit to a first-order Boltzmann equation. E: comparison of absolute maximum current amplitude of INa. F: comparison of peak current density of INa.

Comparison of calcium currents in AL neurons.

We next conducted a quantitative comparison of ICa in individual AL neurons. To measure ICa, the brain preparation was superfused with saline containing 10−7 M TTX, 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. Under these pharmacological conditions, rapid activation and slow inactivation of ICa were observed (Fig. 4A). The I-V relationship of the peak ICa was determined by voltage steps between −80 and 60 mV in 10-mV increments. The voltage dependence for activation was determined from tail currents, which are independent of the changing driving force during a series of varying voltage pulses. The tail currents were evoked by 20-ms pulses applied from −80 to 60 mV in 10-mV increments (Fig. 4B). We first compared the ICa parameters between PNs, spiking LNs, and nonspiking LNs (Fig. 4, C and D). The activation started at command potentials higher than −30 mV in PNs and spiking LNs and higher than −20 mV in nonspiking LNs. The I-V relationship of the currents peaked at command potentials of 10 mV in nonspiking LNs and 20 mV in PNs and spiking LNs. However, abrupt activation of ICa appeared in response to depolarizing voltage step, indicating imperfect space clamp. This could exert influence on the I-V relationship of ICa to some extent. The ICa with poor space clamp could be the result of being electrotonically extensive and/or distant expression of ICa channels from the soma, especially in nonspiking LNs. For these reasons, we next compared the maximum current amplitude and density of ICa in AL neurons. The results show that the peak current amplitude of ICa was significantly greater (∼3.1-fold) in nonspiking LNs compared with spiking LNs and PNs (Fig. 4E). On the other hand, since nonspiking LNs were electrotonically more extensive than spiking LNs and PNs (Table 1), significant increase was no longer presented in the peak current density (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of Ca2+ currents (ICa) in individual AL neurons in whole cell voltage-clamp configuration. A: current traces showing voltage-dependent activation of ICa, measured during the step depolarization in cells loaded with a CsCl patch pipette internal solution and bathed in a solution containing 10−7 M TTX, 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. B: current traces showing tail ICa, measured during the step depolarization in cells loaded with a CsCl patch pipette internal solution and bathed in a solution containing 10−7 M TTX, 5 × 10−3 M 4-AP, and 2 × 10−2 M TEA. C: I-V relationship of ICa. D: I-V relationship of tail ICa. The curves in C and D were fit to a first-order Boltzmann equation. E: comparison of absolute maximum current amplitude of ICa. F: comparison of peak current density of ICa. *P < 0.05.

Functional connectivity of PNs and spiking LNs.

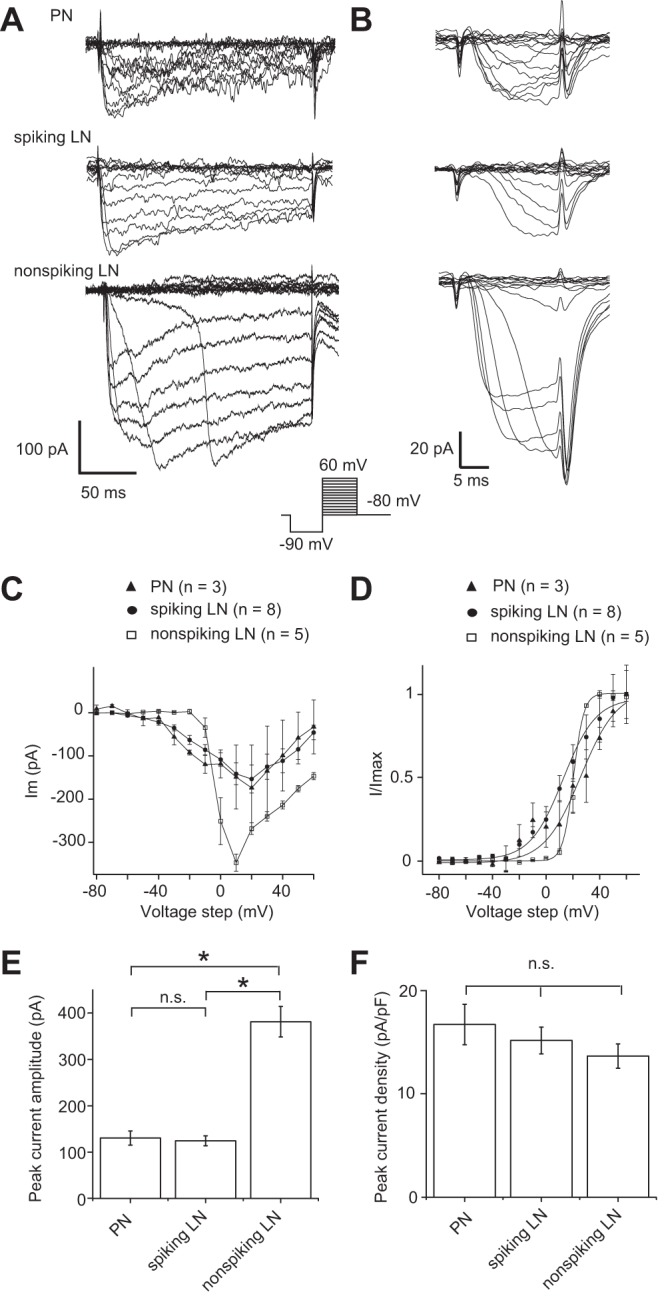

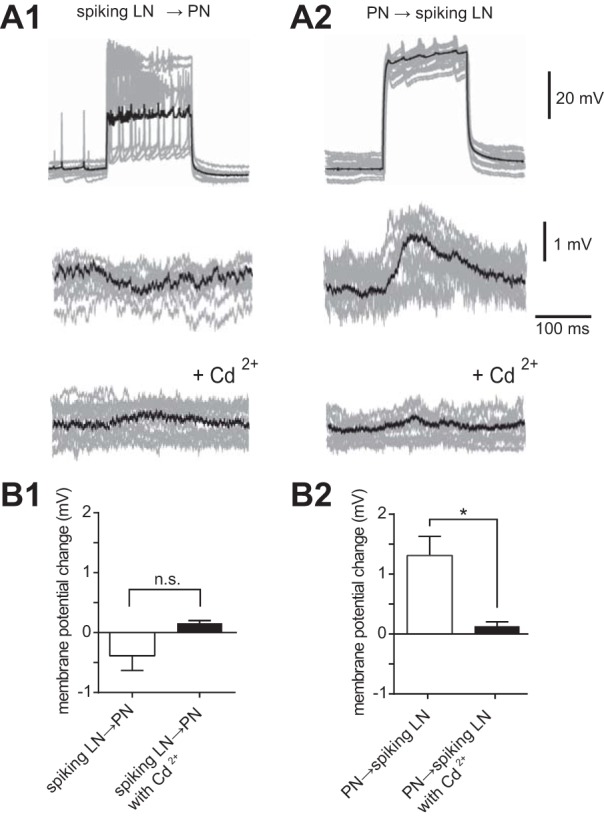

To investigate functional synaptic connectivity between PNs and spiking LNs in the silkmoth AL, we conducted simultaneous recordings from pairs of cell bodies located in medial and lateral cell clusters where the PN and spiking LN somata are present, respectively (summarized in Table 2). We generated presynaptic action potentials with suprathreshold current injections and recorded the postsynaptic responses. Voltage responses recorded in current-clamp mode from the postsynaptic cell indicated functional connectivity between simultaneously recorded neurons. When the spiking LN was stimulated with step-depolarizing currents for 300 ms, which elicited several action potentials, we found that no substantial postsynaptic responses were induced in the paired PN (Figs. 5, A1 and B1). However, when 300-ms step currents were applied to the PN in these paired recordings, postsynaptic depolarization responses were induced in the paired spiking LN (Fig. 5A2). The average amplitude of spiking LN depolarization was about 1.3 ± 0.3 mV (n = 10; Fig. 5, A2 and B2). Furthermore, bath application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ inhibited the excitatory postsynaptic potentials in spiking LNs elicited by PN activation (Fig. 5A2, bottom), indicating that these responses were due to chemical synaptic transmission.

Table 2.

Summary of dual whole cell recordings

| Neuronal Pair | No. of Moths | No. Responded/No. tested | Summary of Response Properties | Electrical Coupling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiking LN vs. PN | 22 | 10/22 | No detectable response in PN by spiking LN activation, but depolarizing response in spiking LN by PN activation | Not found |

| Nonspiking LN vs. PN | 17 | 8/17 | Hyperpolarizing response in PN by nonspiking LN activation, and depolarizing response in nonspiking LN by PN activation | Not found |

| Spiking LN vs. spiking LN | 47 | 13/47 | Reciprocal hyperpolarizing response in one spiking LN by activation of simultaneously recorded another spiking LN | Found |

| Total | 86 | 31/86 | n/a | n/a |

Results for responded pairs are shown in Figs. 5 (spiking LN vs. PN), 6 (nonspiking LN vs. PN), and 7 (spiking LN vs. spiking LN), as well as Fig. 8 for electrical coupling testing. In the paired recording among spiking LN, we refer to the data set of one spiking LN from one electrode as spiking LN 1 and refer to the data set of another spiking LN that is simultaneously recorded from another electrode as spiking LN 2. Detectable functional connections among spiking LNs (13 pairs of 47 tested) always showed a reciprocal response (Fig. 7) as well as nonrectifying electrical coupling (Fig. 8).

Fig. 5.

Functional connectivity of PNs and spiking LNs. A: paired recording of a spiking LN and a PN (n = 10) showing that activation of the PN elicited depolarization responses in the paired spiking LN, whereas activation of the spiking LN induced no substantial responses in the paired PN. Ten individual trials (gray traces) were superimposed and averaged (black trace). A1: presynaptic membrane voltage of the spiking LN in response to a depolarizing current injection (top), simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the PN (middle), and simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the PN with additional application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (bottom). A2: presynaptic membrane voltage of the PN in response to a depolarizing current injection (top), simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the spiking LN (middle), and simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the spiking LN with additional application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (bottom). The data set was obtained in the same cells shown in A1. B: quantification of the change in postsynaptic membrane voltage in the paired recording provided in A. *P < 0.05.

Functional connectivity of PNs and nonspiking LNs.

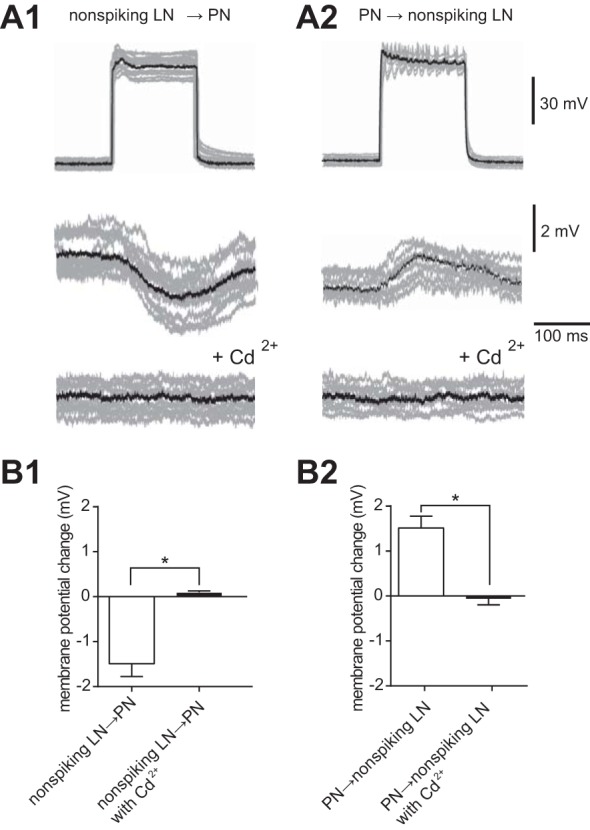

We next examined functional synaptic interactions between PNs and nonspiking LNs (summarized in Table 2). When the nonspiking LN was stimulated with step-depolarizing currents for 300 ms, which elicited a graded depolarizing shift of membrane voltage, substantial postsynaptic hyperpolarization responses were induced in the paired PN, indicating that the nonspiking LNs could elicit detectable inhibitory responses in the PNs (Fig. 6A1). The average amplitude of PN hyperpolarization in response to 300-ms nonspiking LN stimulation was about −1.5 ± 0.5 mV (n = 8; Fig. 6B1). The postsynaptic response of the PN was weakened by administration of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (Fig. 6A1, bottom), indicating that the responses were due to chemical synaptic transmission. However, when 300-ms step currents were applied to the PN, postsynaptic depolarization responses were induced in the paired nonspiking LN (Fig. 6A2). The average amplitude of the depolarization response in nonspiking LNs in response to 300-ms PN stimulation was about 1.4 ± 0.4 mV (n = 8; Fig. 6B2). The postsynaptic response of nonspiking LNs was eliminated by application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (Fig. 6A2, bottom), indicating this observation was due to chemical synaptic transmission.

Fig. 6.

Functional connectivity of PNs and nonspiking LNs. A: paired recording of a PN and a nonspiking LN (n = 8) showing that activation of the PN elicited depolarization responses in the paired nonspiking LN, and activation of the nonspiking LN induced long-lasting hyperpolarization responses in the PN. Eight individual trials (gray traces) were superimposed and averaged (black trace). A1: presynaptic membrane voltage of the nonspiking LN in response to a depolarizing current injection (top), simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the PN (middle), and simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the PN with additional application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (bottom). A2: presynaptic membrane voltage of the PN in response to a depolarizing current injection (top), simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the nonspiking LN (middle), and simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the nonspiking LN with additional application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (bottom). The data set was obtained in the same cells shown in A1. B: quantification of the change in postsynaptic membrane voltage in the paired recording provided in A. *P < 0.05.

Functional connectivity of spiking LNs.

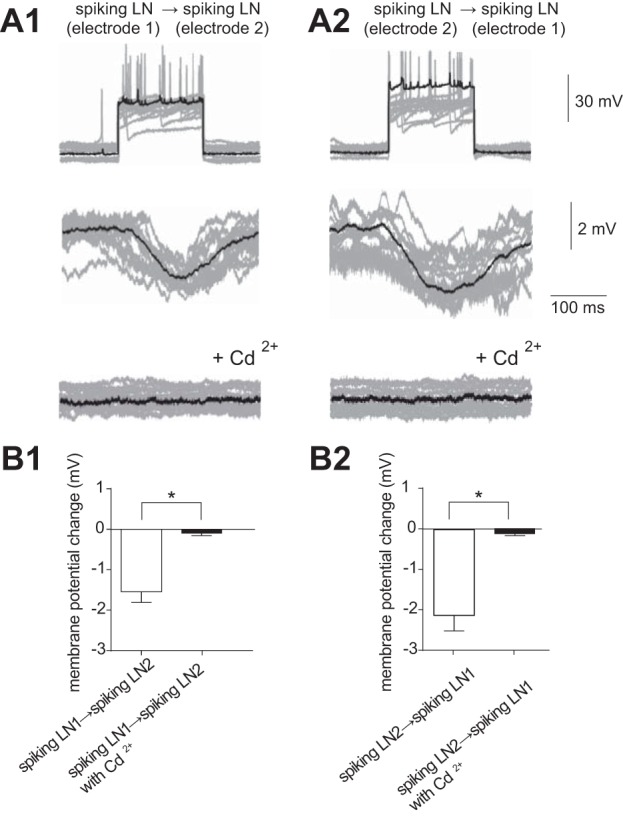

We also performed paired recordings of two spiking LNs to determine whether reciprocal inhibitory connections between spiking LNs could be recorded (summarized in Table 2). Depolarization of one spiking LN recorded from electrode 1, hereafter referred to as spiking LN 1, induced small inhibitory responses in another simultaneously recorded spiking LN, hereafter spiking LN 2 (Fig. 7A). These postsynaptic responses were eliminated by application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (Fig. 7A), indicating reciprocal chemical inhibitory connections. The average amplitude of spiking LN 2 hyperpolarization in response to spiking LN 1 activation was −1.5 ± 0.3 mV (n = 13; Fig. 7B1), and that of spiking LN 1 in response to activation of spiking LN 2 was −2.1 ± 0.4 mV (n = 13; Fig. 7B2).

Fig. 7.

Functional connectivity of spiking LNs. A: paired recording of spiking LNs (n = 13) showing synaptic transmission via chemical synapses. Thirteen individual trials (gray traces) were superimposed and averaged (black trace). A1: presynaptic membrane voltage of the spiking LN in response to a depolarizing current injection (top), simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the spiking LN (middle), and simultaneously recorded postsynaptic membrane voltage of the spiking LN with additional application of 5 × 10−3 M Cd2+ (bottom). A2: the same results were obtained when presynaptic and postsynaptic sites were inverted. The data set was obtained in the same cells shown in A1. B: quantification of the change in postsynaptic membrane voltage in the paired recording provided in A. *P < 0.05.

Electrical synapses between spiking LNs.

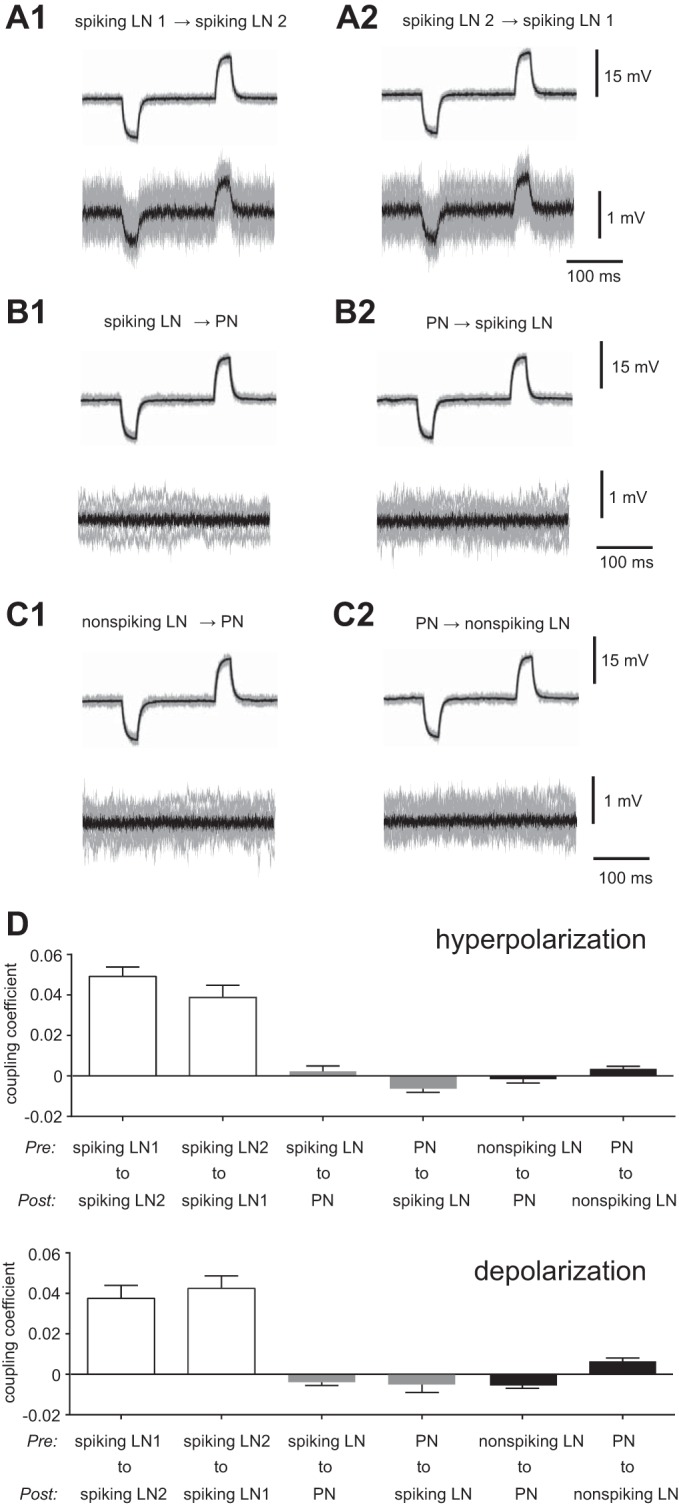

To examine the possibility of electrical coupling, hyperpolarization and subthreshold depolarization were applied to presynaptic cells. Small but detectable membrane potential changes of the same polarity were observed in the postsynaptic cells, indicating the existence of electrical synapses between spiking LNs in the silkmoth AL (Fig. 8A). These responses were always bidirectional and had almost equal magnitude in both hyperpolarizing and depolarizing directions. The mean value of the coupling coefficient for hyperpolarizing injections, determined by the ratio of the voltage response in postsynaptic cells divided by the voltage response in presynaptic cells, was 4.9 ± 0.5% in spiking LN 1 to spiking LN 2 and 3.9 ± 0.6% in spiking LN 2 to spiking LN 1 (n = 13; Fig. 8D). The mean value of the coupling coefficient for subthreshold depolarization was 3.8 ± 0.6% in spiking LN 1 to spiking LN 2 and 4.2 ± 0.6% in spiking LN 2 to spiking LN 1 (n = 13; Fig. 8D). In contrast to the pairs of spiking LNs, no detectable membrane potential changes were observed in the recordings between pairs of spiking LNs and PNs (Fig. 8B) or between pairs of nonspiking LNs and PNs (Fig. 8C). This indicates that the presence of an electrical synapse between PNs and spiking/nonspiking LNs is less likely than an electrical synapse between pairs of spiking LNs. Taken together, our results suggest that the spiking LNs were connected by inhibitory chemical synapses, and electrical synapses were also found between spiking LNs.

Fig. 8.

Electrical coupling. A: electrical coupling between spiking LNs (n = 13). A1: membrane potential changes of the same polarity were induced in postsynaptic cells (bottom) by hyperpolarization and subthreshold depolarization in presynaptic cells (top). A2: the same results were obtained when presynaptic and postsynaptic sites were inverted. B: no electrical coupling between PNs and spiking LNs (n = 10). B1: Membrane potential in postsynaptic cells (bottom) by hyperpolarization and subthreshold depolarization in presynaptic cells (top). B2: the same results were obtained when presynaptic and postsynaptic sites were inverted. C: no electrical coupling between PNs and nonspiking LNs (n = 8). C1: membrane potential in postsynaptic cells (bottom) by hyperpolarization and subthreshold depolarization in presynaptic cells (top). C2: the same results were obtained when presynaptic and postsynaptic sites were inverted. D: quantification showing the coupling coefficient in paired recordings from A–C, which was determined as the ratio of the voltage response in the noninjected cell divided by the voltage response in the injected cell. The results for the hyperpolarization current in the presynaptic cell are shown at top, and the results for the depolarization current in the presynaptic cell are shown at bottom.

DISCUSSION

The morphology of both PNs and LNs in the silkmoth AL has been comprehensively characterized (Namiki and Kanzaki 2011; Seki and Kanzaki 2008). However, their intrinsic membrane properties and functional connectivity are relatively unknown. We found distinct physiological properties between two morphologically distinct LNs, as well as differences in their functional connectivity to PNs. The intrinsic neuronal properties and functional synaptic connectivity examined here provide a mechanistic framework for the neuronal machinery of information processing in silkmoth olfaction.

Two distinct types of LNs in the silkmoth AL.

We provide evidence that LNs in the silkmoth AL include not only a spiking type but also a nonspiking type that does not have Na+ action potentials. Strikingly, these two types of LNs had clear correlations with their morphology. Based on our previous morphological classification, spiking LNs are identified as the MGC-allGs-sparse morphological type, whereas nonspiking LNs are the MGC-allGs-dense morphological type. This suggests distinct physiological properties between the two morphologically distinct types of LNs in the silkmoth AL. We previously conducted comprehensive immunohistochemical analysis of AL neurons (Seki and Kanzaki 2008) and found that both of the MGC-allGs-sparse (“spiking LNs” in the present study) and MGC-allGs-dense (“nonspiking LNs” in the present study) morphological types of LNs are GABA immunoreactive. Accordingly, we believe that at least one of the neurotransmitters of these two types of LNs is GABA.

Functional synaptic connectivity in the AL.

During dual recording, we could not observe a detectable change in PN membrane potential when depolarizing current was injected into the spiking LN. However, a membrane potential change toward hyperpolarization was clearly observed in the PN when depolarizing current was injected into the nonspiking LN.

One possible way to interpret this lack of detectable change in PNs in response to spiking LN activation is that the synapses of spiking LNs preferentially target ORNs rather than PNs. Evidence that LNs act at least partially through presynaptic inhibition on ORNs, without inhibiting PNs directly, has been reported in the Drosophila AL (Olsen and Wilson 2008). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the postsynaptic response was too small to observe by somatic recording if the membrane voltage was spatially attenuated, which has been shown in previous studies combining both experimental and computational estimation (Gouwens and Wilson 2009; Kepler and Marder 1993; Prinz et al. 2003; Soto-Trevino et al. 2005; Takashima et al. 2006; Takashima and Takahata 2000). Indeed, the advantage of electrotonically compact paired patch-clamp recordings to observe the postsynaptic response has been demonstrated in the P. americana AL (Warren and Kloppenburg 2014).

Furthermore, it has been shown that a single inhibitory LN is not enough to trigger a postsynaptic PN response in the Drosophila AL, but that the response becomes detectable if the LNs were collectively and simultaneously activated (Huang et al. 2010). However, this experiment cannot exclude the possibility of neurotransmitter spillover from the presynaptic inhibition site to postsynaptic receptors, which is widely known to occur in the mammalian retina and central nervous system (CNS) (Houston et al. 2009; Park et al. 2007; Scanziani 2000). Collective and simultaneous activation of inhibitory LNs may lead to abundant neurotransmitter release, and in this case, spillover activation of the postsynaptic receptor in PNs is likely to occur. Although further studies are warranted to provide a firm conclusion, what is clear in our study is that activation of a single spiking LN causes no detectable postsynaptic response in PNs, at least using our somatic recording configuration.

On the other hand, we showed that activation of a single nonspiking LN elicited an inhibitory postsynaptic response in the PN. This was clearly detected even in the somatic recordings. We therefore suggest that synaptic strength of the inhibitory input from a nonspiking LN to a PN is powerful enough to be observed in our somatic recording configuration.

Chemical and electrical synapses among spiking LNs.

We found reciprocal inhibitory postsynaptic responses between spiking LNs. When spike trains were triggered in one spiking LN, an average of the other spiking LN membrane potential showed a shift toward hyperpolarization. Spike-evoked hyperpolarization represents the functional existence of hyperpolarizing chemical transmission between spiking LNs.

In addition to chemical synapses, we found the presence of electrical coupling between spiking LNs. The coupling coefficient in our electrophysiological results was smaller than the one usually seen in the mammalian CNS (Galarreta and Hestrin 1999, 2002). This could be due to signal attenuation, because the soma is electronically distant from contact sites in invertebrate CNS. Indeed, the coupling coefficient in the Drosophila electrical synapse between excitatory LNs and PNs was similar to our result (Huang et al. 2010; Yaksi and Wilson 2010).

Functional implication for olfactory processing.

What is the functional significance of these two distinct types of LNs for olfactory information processing? To propagate electrical signals, spiking LNs generate an all-or-none Na+ action potential, whereas nonspiking LNs depolarize the membrane potential in a graded fashion. An action potential can be passed on without electronic decline regardless of the distance of the transmission, but the information is converted to a binary digital format, reducing the amount of information that can be represented per single cell (Juusola and French 1997). The reduction of information capacity calls for ensemble activity of spiking neurons to fully represent information, demonstrated by population coding (Gray et al. 1989). Many types of interneurons are interconnected by both electrical and GABAergic synapses in mammalian neocortical circuits or the vertebrate retina, and the functional significance of coexisting electrical and GABAergic synapses in promotion of synchronous activity within the network has been suggested (Bacci and Huguenard 2006; Galarreta and Hestrin 2001; Hu and Bloomfield 2003; Scanziani 2000; Vervaeke et al. 2010; Volgyi et al. 2013). Our finding that spiking LNs are connected by both electrical and chemical synapses suggests that spiking LNs may have a similar function in the silkmoth AL.

In addition, we discussed the possibility that the synaptic target of spiking LNs favored ORNs, rather than PNs, as part of a presynaptic inhibitory scheme. In particular, the spiking LNs spontaneously fire even without presentation of olfactory stimulation, and this may play a role as a high-pass temporal filter to reduce the low-frequency ORN noise entering the PN (Bhandawat et al. 2007; Olsen et al. 2010).

Nonspiking LNs do not use all-or-nothing Na+ action potentials, but instead use graded changes in membrane voltage to transmit information. Using a graded change in membrane potential enables nonspiking LNs to conduct an analog coding scheme that confers a broad dynamic range of information per single cell (de Ruyter van Steveninck and Laughlin 1996; Juusola and French 1997; Papadopoulou et al. 2011). Since nonspiking LNs are electrotonically more extensive than spiking LNs, it is likely that nonspiking LNs generate graded postsynaptic inhibition to the PN only in the case of strong ORN input caused by a high concentration of odor stimuli. If so, such a graded postsynaptic inhibition might be useful for shaping GABAergic mechanisms that suppress PN responses only in the presence of strong ORN inputs, indicating that activation of LNs occurs in a stimulus-dependent fashion in the silkmoth AL (Fujiwara et al. 2014; Tabuchi et al. 2013). From the above, we suggest that spiking LNs spontaneously send presynaptic inhibition to ORNs, contributing to the suppression of low-frequency noise from entering the PN, whereas nonspiking LNs send postsynaptic inhibition to PNs only when there is a high concentration of odor present. Thus we propose a model in which spiking and nonspiking LNs modulate AL signal transfer in a stimulus-dependent fashion, acting together as a temporal bandpass filter in a circuit mechanism that optimizes processing performance, which is analogous to the vertebrate retina (Armstrong-Gold and Rieke 2003).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the nonspiking LNs of the silkmoth AL are distinguished by their morphology, intrinsic membrane properties, and functional synaptic connectivity relative to spiking LNs, thus providing a fundamental framework for AL microcircuits.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS; to M. Tabuchi) and JSPS Scientific Research (B) Grant 21370029 (to R. Kanzaki).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.T., S.N., T.S., K.N., and R.K. conception and design of research; M.T., L.D., and S.I. performed experiments; M.T. analyzed data; M.T. and R.K. interpreted results of experiments; M.T. prepared figures; M.T., K.N., and R.K. drafted manuscript; M.T., S.N., T.S., K.N., and R.K. edited and revised manuscript; M.T., L.D., S.I., S.N., T.S., K.N., and R.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Haruna Kawasaki (University of Tsukuba) for technical assistance with performance of single-cell RT-PCR and Dr. Hideki Sezutsu (National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences) for w1.pnd silkmoths.

Present address of M. Tabuchi: Dept. of Neurology, Johns Hopkins Univ., Baltimore, MD 21287.

Present address of S. Namiki: Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Farm Research Campus, Ashburn, VA 20147.

REFERENCES

- Armstrong-Gold CE, Rieke F. Bandpass filtering at the rod to second-order cell synapse in salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) retina. J Neurosci 23: 3796–3806, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci A, Huguenard JR. Enhancement of spike-timing precision by autaptic transmission in neocortical inhibitory interneurons. Neuron 49: 119–130, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg BG, Schachtner J, Homberg U. Gamma-aminobutyric acid immunostaining in the antennal lobe of the moth Heliothis virescens and its colocalization with neuropeptides. Cell Tissue Res 335: 593–605, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandawat V, Olsen SR, Gouwens NW, Schlief ML, Wilson RI. Sensory processing in the Drosophila antennal lobe increases reliability and separability of ensemble odor representations. Nat Neurosci 10: 1474–1482, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson MA, Diesner M, Schachtner J, Nassel DR. Multiple neuropeptides in the Drosophila antennal lobe suggest complex modulatory circuits. J Comp Neurol 518: 3359–3380, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YH, Spletter ML, Yaksi E, Leong JC, Wilson RI, Luo L. Diversity and wiring variability of olfactory local interneurons in the Drosophila antennal lobe. Nat Neurosci 13: 439–449, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen TA, Waldrop BR, Harrow ID, Hildebrand JG. Local interneurons and information processing in the olfactory glomeruli of the moth Manduca sexta. J Comp Physiol A 173: 385–399, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen TA, Waldrop BR, Hildebrand JG. GABAergic mechanisms that shape the temporal response to odors in moth olfactory projection neurons. Ann NY Acad Sci 855: 475–481, 1998a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen TA, Waldrop BR, Hildebrand JG. Multitasking in the olfactory system: context-dependent responses to odors reveal dual GABA-regulated coding mechanisms in single olfactory projection neurons. J Neurosci 18: 5999–6008, 1998b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruyter van Steveninck RR, Laughlin SB. Light adaptation and reliability in blowfly photoreceptors. Int J Neural Syst 7: 437–444, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes IM, Freeman FM, Bacon JP, Davies JA. Molecular basis of gap junctional communication in the CNS of the leech Hirudo medicinalis. J Neurosci 24: 886–894, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Kazawa T, Sakurai T, Fukushima R, Uchino K, Yamagata T, Namiki S, Haupt SS, Kanzaki R. Odorant concentration differentiator for intermittent olfactory signals. J Neurosci 34: 16581–16593, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusca D, Husch A, Baumann A, Kloppenburg P. Choline acetyltransferase-like immunoreactivity in a physiologically distinct subtype of olfactory nonspiking local interneurons in the cockroach (Periplaneta americana). J Comp Neurol 521: 3556–3569, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Electrical and chemical synapses among parvalbumin fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons in adult mouse neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 12438–12443, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. A network of fast-spiking cells in the neocortex connected by electrical synapses. Nature 402: 72–75, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Spike transmission and synchrony detection in networks of GABAergic interneurons. Science 292: 2295–2299, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Connors BW. Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature 402: 75–79, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouwens NW, Wilson RI. Signal propagation in Drosophila central neurons. J Neurosci 29: 6239–6249, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, Konig P, Engel AK, Singer W. Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature 338: 334–337, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson BS, Anton S. Function and morphology of the antennal lobe: new developments. Annu Rev Entomol 45: 203–231, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand JG, Shepherd GM. Mechanisms of olfactory discrimination: converging evidence for common principles across phyla. Annu Rev Neurosci 20: 595–631, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins SG, Homberg U, Kingan TG, Christensen TA, Hildebrand JG. Immunocytochemistry of GABA in the antennal lobes of the sphinx moth Manduca sexta. Cell Tissue Res 244: 243–252, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston CM, Bright DP, Sivilotti LG, Beato M, Smart TG. Intracellular chloride ions regulate the time course of GABA-mediated inhibitory synaptic transmission. J Neurosci 29: 10416–10423, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu EH, Bloomfield SA. Gap junctional coupling underlies the short-latency spike synchrony of retinal alpha ganglion cells. J Neurosci 23: 6768–6777, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zhang W, Qiao W, Hu A, Wang Z. Functional connectivity and selective odor responses of excitatory local interneurons in Drosophila antennal lobe. Neuron 67: 1021–1033, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husch A, Paehler M, Fusca D, Paeger L, Kloppenburg P. Calcium current diversity in physiologically different local interneuron types of the antennal lobe. J Neurosci 29: 716–726, 2009a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husch A, Paehler M, Fusca D, Paeger L, Kloppenburg P. Distinct electrophysiological properties in subtypes of nonspiking olfactory local interneurons correlate with their cell type-specific Ca2+ current profiles. J Neurophysiol 102: 2834–2845, 2009b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwano M, Kanzaki R. Immunocytochemical identification of neuroactive substances in the antennal lobe of the male silkworm moth Bombyx mori. Zoolog Sci 22: 199–211, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juusola M, French AS. The efficiency of sensory information coding by mechanoreceptor neurons. Neuron 18: 959–968, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama H, Wilson RI. Origins of correlated activity in an olfactory circuit. Nat Neurosci 12: 1136–1144, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler TB, Marder E. Spike initiation and propagation on axons with slow inward currents. Biol Cybern 68: 209–214, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent G, Davidowitz H. Encoding of olfactory information with oscillating neural assemblies. Science 265: 1872–1875, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavialle-Defaix C, Jacob V, Monsempes C, Anton S, Rospars JP, Martinez D, Lucas P. Firing and intrinsic properties of antennal lobe neurons in the Noctuid moth Agrotis ipsilon. Biosystems, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WW, Wilson RI. Glutamate is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the Drosophila olfactory system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 10294–10299, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod K, Laurent G. Distinct mechanisms for synchronization and temporal patterning of odor-encoding neural assemblies. Science 274: 976–979, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malun D. Synaptic relationships between GABA-immunoreactive neurons and an identified uniglomerular projection neuron in the antennal lobe of Periplaneta americana: a double-labeling electron microscopic study. Histochemistry 96: 197–207, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namiki S, Kanzaki R. Heterogeneity in dendritic morphology of moth antennal lobe projection neurons. J Comp Neurol 519: 3367–3386, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SR, Bhandawat V, Wilson RI. Divisive normalization in olfactory population codes. Neuron 66: 287–299, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SR, Wilson RI. Lateral presynaptic inhibition mediates gain control in an olfactory circuit. Nature 452: 956–960, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou M, Cassenaer S, Nowotny T, Laurent G. Normalization for sparse encoding of odors by a wide-field interneuron. Science 332: 721–725, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JB, Skalska S, Son S, Stern JE. Dual GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in rat presympathetic paraventricular nucleus neurons. J Physiol 582: 539–551, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz AA, Billimoria CP, Marder E. Alternative to hand-tuning conductance-based models: construction and analysis of databases of model neurons. J Neurophysiol 90: 3998–4015, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisenman CE, Dacks AM, Hildebrand JG. Local interneuron diversity in the primary olfactory center of the moth Manduca sexta. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 197: 653–665, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachse S, Galizia CG. Role of inhibition for temporal and spatial odor representation in olfactory output neurons: a calcium imaging study. J Neurophysiol 87: 1106–1117, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M. GABA spillover activates postsynaptic GABA(B) receptors to control rhythmic hippocampal activity. Neuron 25: 673–681, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki Y, Kanzaki R. Comprehensive morphological identification and GABA immunocytochemistry of antennal lobe local interneurons in Bombyx mori. J Comp Neurol 506: 93–107, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki Y, Rybak J, Wicher D, Sachse S, Hansson BS. Physiological and morphological characterization of local interneurons in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J Neurophysiol 104: 1007–1019, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Claridge-Chang A, Sjulson L, Pypaert M, Miesenbock G. Excitatory local circuits and their implications for olfactory processing in the fly antennal lobe. Cell 128: 601–612, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao YM, Dong K, Tang ZH, Zhang CX. Molecular characterization of a sodium channel gene from the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 39: 145–151, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda T, Itoyama K. Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase: a key regulatory enzyme for insect metamorphosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 11986–11991, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Trevino C, Rabbah P, Marder E, Nadim F. Computational model of electrically coupled, intrinsically distinct pacemaker neurons. J Neurophysiol 94: 590–604, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopfer M, Bhagavan S, Smith BH, Laurent G. Impaired odour discrimination on desynchronization of odour-encoding neural assemblies. Nature 390: 70–74, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi M, Sakurai T, Mitsuno H, Namiki S, Minegishi R, Shiotsuki T, Uchino K, Sezutsu H, Tamura T, Haupt SS, Nakatani K, Kanzaki R. Pheromone responsiveness threshold depends on temporal integration by antennal lobe projection neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 15455–15460, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, Hikosaka R, Takahata M. Functional significance of passive and active dendritic properties in the synaptic integration by an identified nonspiking interneuron of crayfish. J Neurophysiol 96: 3157–3169, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, Takahata M. Electrophysiological and theoretical analysis of depolarization-dependent outward currents in the dendritic membrane of an identified nonspiking interneuron in crayfish. J Comput Neurosci 9: 187–205, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervaeke K, Lorincz A, Gleeson P, Farinella M, Nusser Z, Silver RA. Rapid desynchronization of an electrically coupled interneuron network with sparse excitatory synaptic input. Neuron 67: 435–451, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volgyi B, Pan F, Paul DL, Wang JT, Huberman AD, Bloomfield SA. Gap junctions are essential for generating the correlated spike activity of neighboring retinal ganglion cells. PLoS One 8: e69426, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren B, Kloppenburg P. Rapid and slow chemical synaptic interactions of cholinergic projection neurons and GABAergic local interneurons in the insect antennal lobe. J Neurosci 34: 13039–13046, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Ai H, Yokohari F. Spatio-temporal activity patterns of odor-induced synchronized potentials revealed by voltage-sensitive dye imaging and intracellular recording in the antennal lobe of the cockroach. Front Syst Neurosci 6: 55, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr M, Laurent G. Relationship between afferent and central temporal patterns in the locust olfactory system. J Neurosci 19: 381–390, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Laurent G. Role of GABAergic inhibition in shaping odor-evoked spatiotemporal patterns in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J Neurosci 25: 9069–9079, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Mainen ZF. Early events in olfactory processing. Annu Rev Neurosci 29: 163–201, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksi E, Wilson RI. Electrical coupling between olfactory glomeruli. Neuron 67: 1034–1047, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]