CONSPECTUS

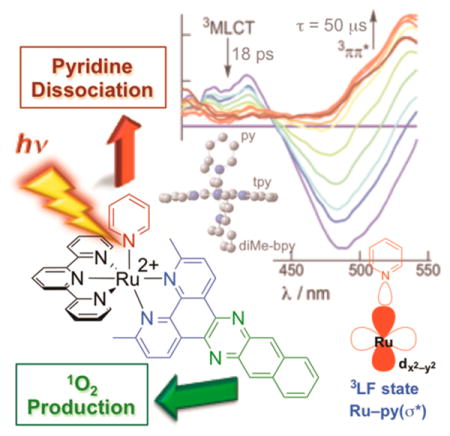

Uncovering the factors that govern the electronic structure of Ru(II)–polypyridyl complexes is critical in designing new compounds for desired photochemical reactions, and strategies to tune excited states for ligand dissociation and 1O2 production are discussed herein. The generally accepted mechanism for photoinduced ligand dissociation proposes that population of the dissociative triplet ligand field (3LF) state proceeds through thermal population from the vibrationally cooled triplet metal-to-ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) state; however, temperature-dependent emission spectroscopy provides varied activation energies using the emission and ligand exchange quantum yields for [Ru(bpy)2(L)2]2+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine; L = CH3CN or py). This suggests that population of the 3LF state proceeds from the vibrationally excited 3MLCT state. Because the quantum yield of ligand dissociation for nitriles is much more efficient than that for py, steric bulk was introduced into the ligand set to distort the pseudo-octahedral geometry and lower the energy of the 3LF state. The py dissociation quantum yield with 500 nm irradiation in a series of [Ru(tpy)(NN)(py)]2+ complexes (tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine; NN = bpy, 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (Me2bpy), 2,2′-biquinoline (biq)) increases by 2–3 orders of magnitude with the sterically bulky Me2bpy and biq ligands relative to bpy. Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy reveals population of the 3LF state within 3–7 ps when NN is bulky, and density functional theory calculations support stabilized 3LF states. Dual activity via ligand dissociation and 1O2 production can be achieved by careful selection of the ligand set to tune the excited-state dynamics. Incorporation of an extended π system in Ru(II) complexes such as [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ (dppn = benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) and [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ (Me2dppn = 3,6-dimethylbenzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) introduces low-lying, long-lived dppn/Me2dppn 3ππ* excited states that generate 1O2. Similar to [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+, photodissociation of CH3CN occurs upon irradiation of [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+, although with lower efficiency because of the presence of the 3ππ* state. The steric bulk in [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ is critical in facilitating the photoinduced py dissociation, as the analogous complex [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ produces 1O2 with near-unit efficiency. The ability to tune the relative energies of the excited states provides a means to design potentially more active drugs for photochemotherapy because the photorelease of drugs can be coupled to the therapeutic action of reactive oxygen species, effecting cell death via two different mechanisms. The lessons learned about tuning of the excited-state properties can be applied to the use of Ru(II)–polypyridyl compounds in a variety of applications, such as solar energy conversion, sensors and switches, and molecular machines.

INTRODUCTION

Excited states of Ru(II) complexes have been used in solar energy conversion,1–5 in charge transfer reactions,6,7 as sensors and switches,8,9 and as potential therapeutic agents in photochemotherapy (PCT) and imaging.10–16 Although many complexes are derived from [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine) (Figure 1a),17 these applications often have different demands. For example, the excited-state redox potential is crucial in solar energy schemes and charge transfer reactions, which often require long-lived triplet metal-to-ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) excited states, whereas strong luminescence and sensitivity to the environment have been important in sensor applications. In contrast, complexes developed for PCT typically require high yields of photo-induced ligand exchange for prodrug delivery or to achieve binding of the metal to biomolecules, which in turn results in short 3MLCT lifetimes with low luminescence yields. In order to tune the relative energies of the excited states to achieve the desired properties, an understanding of the factors that affect the electronic structure of Ru(II) complexes is necessary.

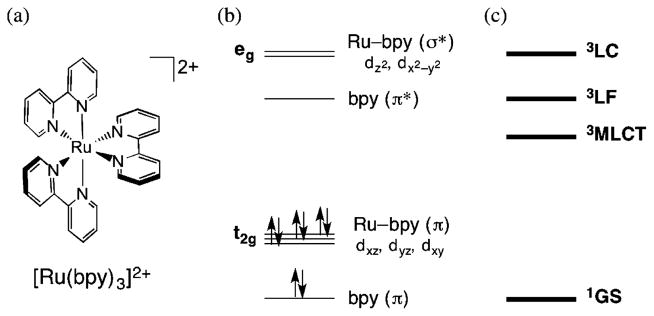

Figure 1.

(a) Molecular structure and simplified (b) MO and (c) state diagrams of [Ru(bpy)3]2+.

The electronic structure and excited-state dynamics of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and related complexes have been the subject of numerous reviews.17 Figure 1b presents a simplified diagram showing the frontier molecular orbitals (MOs) of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ in a pseudo-octahedral field, for which the lowest-energy 1MLCT transition has a maximum at 452 nm (ε = 14 600 M−1 cm−1) and the bpy ππ* transitions are observed at 285 nm (ε = 87 000 M−1 cm−1) in water.17 Ultrafast 1MLCT → 3MLCT intersystem crossing (ISC) was reported in [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (15–40 fs),18,19 and to our knowledge, significantly lower ISC rates have not been reported for Ru(II) complexes. Therefore, with the exception of charge injection into semiconductors,20 the excited-state chemistry of Ru(II) complexes takes place from the triplet manifold. The low-lying triplet excited states of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ are schematically shown in Figure 1c, where the metal-centered triplet ligand field (3LF) state(s) involve transitions from the t2g-type orbitals to the eg-type orbitals, and the triplet ligand-centered (3LC) states arise from movement of an electron from the bpy(π) MOs to the bpy(π*) MOs. In [Ru(bpy)3]2+, the 3MLCT state is emissive (λem = 607 nm, τ = 620 ns, Φ = 0.042 in water at 298 K).17 The lifetimes of Ru(II) complexes in which the 3LC excited state falls below the 3MLCT state are similar to those of the 3ππ* state of the free ligand, and these complexes generally are not emissive, exhibit long lifetimes, and feature efficient 1O2 sensitization.21–24 In contrast, stabilization of the 3LF states results in photoinduced ligand exchange, which may be accomplished by introducing distortions around the metal center. These distortions reduce the orbital overlap and lower the energy of the eg-type orbitals,15 thus decreasing the energy of the 3LF states, sometimes below that of the 3MLCT state.25

The present Account focuses on the effect of structural changes to ruthenium(II) complexes on the excited-state properties and reactivity. Of particular interest are compounds that undergo photoinduced ligand exchange and those that generate 1O2, as well as new complexes designed in such a way that both processes are operative in the same complex upon irradiation with low-energy light. This dual reactivity has the potential to be useful in applications related to PCT, where cell death may be achieved via two different mechanisms by the same molecule.

ACTIVATION BARRIER TO PHOTOINDUCED LIGAND EXCHANGE

It is well-established that deactivation of the emissive 3MLCT state in Ru(II) complexes proceeds via thermal population of the 3LF states, which reduces the lifetime of the former. For applications that require charge transfer or high luminescence quantum yields, researchers aim to maximize the gap between the 3MLCT and 3LF states, which minimizes deactivation through the latter. In contrast, maximizing photoinduced ligand exchange of ruthenium(II) complexes, such as in the release of active molecules to biological targets and to gain understanding of their function, to inhibit enzymes, and to generate reactive species that can covalently bind to DNA, requires efficient population of the dissociative 3LF states.11,13–15 One limitation is the relatively low quantum yield of ligand exchange in some complexes.

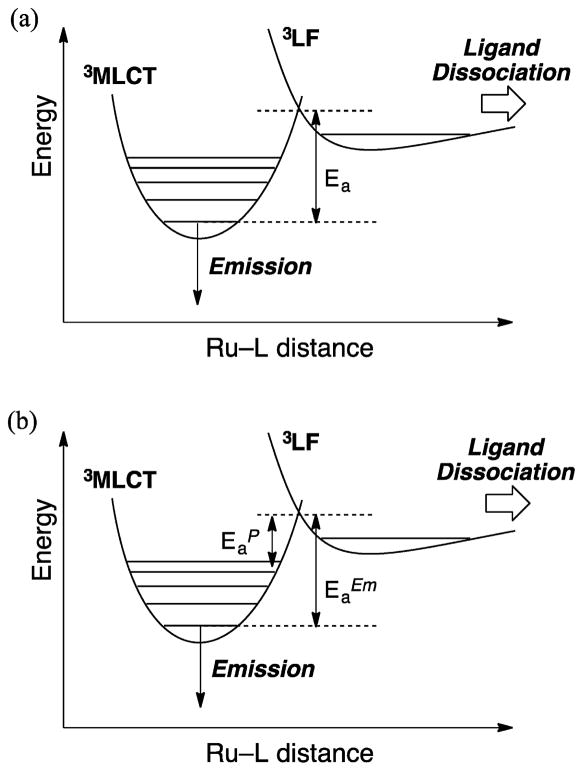

It has been generally accepted that the formation of photosubstituted products in Ru(II)–polypyridyl complexes proceeds through thermal population of the dissociative 3LF state(s) from the vibrationally cooled emissive 3MLCT state (3MLCTv=0).26 It is also established that deactivation of the emissive 3MLCTv=0 state proceeds via population of the low-lying 3LF state(s), as depicted in Figure 2a. If it is assumed that the only source of photoinduced ligand exchange is population of the 3LF state from 3MLCTv=0, then Arrhenius plots of both the photochemical yield and the emission intensity should give rise to the same activation energy, Ea (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the potential energy surfaces showing (a) the activation energy, Ea, for going from 3MLCTv=0 to the 3LF state and (b) the proposed sources of and .

Plots of ln(Φ) versus 1/T for the photoanation reactions of [Ru(bpy)2(L)2]2+ (L = py, CH3CN) to generate the corresponding [Ru(bpy)2(L)Cl]+ product in the presence of excess tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBACl) in CH2Cl2 were reported to result in Ea ≈ 700 cm−1,27 whereas changes in the emission lifetime of [Ru(bpy)2(py)2]2+ with temperature result in Ea = 2758 cm−1.28 However, these activation barriers were measured in two different temperature regimes, which can account for the different values. In addition, there have been other reports on the discrepancy between the magnitudes of Ea determined from emission and photochemical yields as well as from emission intensity and lifetime data.28,29 The concluding remarks in both reports point to possible direct population of the 3LF state from the 1MLCT state together with population of the emissive 3MLCT state.28,29

To gain further understanding of the photoinduced ligand exchange in [Ru(bpy)2(L)2]2+ (L = CH3CN, py), the activation energies for photoanation to generate the corresponding complexes [Ru(bpy)2(L)Cl]+, , were measured over the same temperature range as for the value from the changes in emission intensity, , in 4:1 ethanol/methanol above the glass transition temperature.30 The experiments were conducted in a cryostat placed in the sample compartment of the fluorimeter, and the decrease in the emission intensity as the temperature was raised was monitored in the absence of anion immediately after excitation to determine . The change in emission intensity as a function of irradiation time in the presence of 20 mM TBACl was used to calculate the value of , and the results are listed in Table 1.30 It is evident from Table 1 that for both complexes the value of is significantly lower than that of . It may be concluded that the ligand exchange does not proceed from 3MLCTv=0, as shown in Figure 2a. Instead, the population of the dissociative 3LF state must have a different origin, as previously proposed by us,31 and may include direct ISC from the Franck–Condon 1MLCT state, internal conversion (IC) from a higher-energy 3MLCT state, or IC from the vibrationally excited lowest-energy 3MLCT state (3MLCTv≫1). The latter situation is depicted in Figure 2b, where vibrational cooling competes with IC from a vibrational level well above v = 0, as previously proposed from ultrafast work.32

Table 1.

Quantum Yields of Photoinduced Ligand Exchange for [Ru(bpy)2(L)2]2+ Complexes, Absorption Maxima, and Activation Barriers with the Corresponding Temperature Ranges

| L | ΦCla | λabs/nmb |

|

|

T/K | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3CN | 0.31 | 420 | 1310 ± 65 | 515 ± 100 | 130–170 | ||

| py | 0.17 | 460 | 2040 ± 100 | 940 ± 85 | 180–230 |

At 25 °C in CH2Cl2 with 20 mM TBACl (λirr = 400 nm).

In H2O.

Irradiated at the absorption maximum.

In order for efficient ligand dissociation to be observed, population of the 3LF state must compete with generation of 3MLCTv=0. In systems such as [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+, there must be strong vibrational coupling between the MLCT (singlet or triplet) and 3LF states, which is reduced in [Ru(bpy)2(py)2]2+. For example, strong vibrational coupling is believed to play a role in the ultrafast ISC of <100 fs in Cr(acac)3 (acac = acetylacetonate), but interestingly, it decreases by over an order of magnitude when the ligand’s peripheral methyl groups are replaced by tert-butyl substituents in Cr(t-Bu-acac)3.33 In addition to nitriles, thioethers undergo photoinduced ligand dissociation with greater quantum yields than their ammine counterparts, and the 3MLCT states of the former were calculated to exhibit elongated Ru–S bonds, which may be related to MLCT/LF mixing.34

ENHANCED PHOTOINDUCED LIGAND EXCHANGE WITH STERIC BULK

To increase the quantum yield for pyridine exchange through enhanced population of the 3LF state, sterically bulky ligands were incorporated to distort the pseudo-octahedral geometry around the metal center. The decrease in the energy of the 3LF state(s) as a function of increasing steric bulk was demonstrated for a series of complexes [Ru(NN)3]2+ with NN = bpy, 6-methyl-2,2′-bipyridine (6-Mebpy), and 4,4′,6,6′-tetramethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (Me4bpy) using ultrafast transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy.25 On the basis of the difference in the decay of the 3MLCT state and recovery of the ground state, it was shown that the rate of population of a 3LF state from the 3MLCT state increased by an order of magnitude in going from [Ru(6-Mebpy)3]2+ to the more sterically demanding [Ru-(Me4bpy)3]2+, with 3MLCT lifetimes of 1.6 and 0.16 ps, respectively.25 Distortions around the metal lead to a decrease in the calculated energy of the 3LF state by ~4000 cm−1 in [Ru(6-Mebpy)3]2+ and ~7000 cm−1 in [Ru(Me4bpy)3]2+ relative to that in [Ru(bpy)3]2+. Therefore, while the 3LF state lies above the 3MLCT state in the latter, it falls below the 3MLCT state in the former, resulting in fast 3MLCT decay to populate the 3LF state.

The enhanced population of the 3LF state(s) in ruthenium-(II) complexes with bulky ligands leads to greater photo-induced ligand exchange. For example, photodissociation of 2,2′-biquinoline (biq) from [Ru(biq)(phen)2]2+ (phen = 1,10-phenathroline) and [Ru(biq)2(phen)]2+ in H2O occurs with λirr ≥ 600 nm, while this photoactivity is not observed in [Ru(phen)3]2+.35 The crystal structures of the biq complexes reveal lengthened Ru–N bonds compared with those in [Ru(phen)3]2+ as well as significant twisting of biq along the C–C bond connecting the two quinoline moieties and bending of biq by ~20° out of the normal plane. Similar photoreactivity was reported for [Ru(biq)2(bpy)]2+ in CH3CN.36 The presence of methyl, phenyl, or chloro substituents positioned toward the Ru(II) center also induces geometric distortions and facilitates photosubstitution of the bulky bidentate ligands with solvent molecules.15,37,38

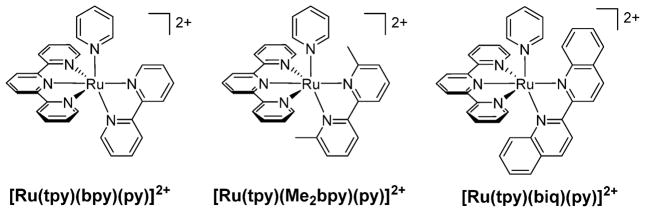

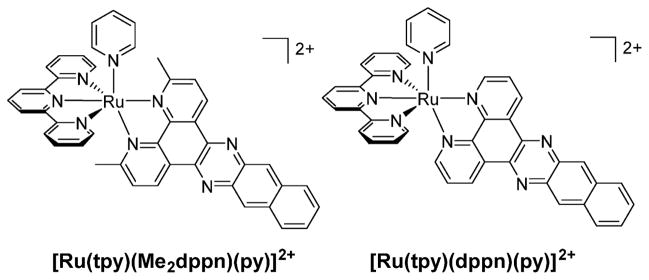

To increase the photodissociation quantum yield of pyridine from pseudo-octahedral ruthenium(II) complexes, steric bulk was introduced in the series [Ru(tpy)(NN)(py)]2+ (tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine; NN = bpy, 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridinep(Me2bpy), biq) (Figure 3).39 The lowest-energy electronic transition observed in [Ru(tpy)(NN)(py)]2+ (NN = bpy, Me2bpy) is the Ru(dπ) → tpy(π*) 1MLCT transition with maxima at 468 nm (8120 M−1 cm−1) and 471 nm (8020 M−1 cm−1), respectively, whereas that in [Ru(tpy)(biq)(py)]2+ is assigned as the Ru(dπ) → biq(π*) 1MLCT transition at 530 nm (9020 M−1 cm−1). Photoinduced exchange of py is not observed in [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ (Φ500 < 0.0001), but irradiation of [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(biq)-(py)]2+ in CH3CN generates the corresponding products [Ru(tpy)(NN)(CH3CN)]2+ (NN = Me2bpy, biq) with Φ500 = 0.16(1) and 0.033(1), respectively (Table 2). All three complexes are stable in CH3CN and H2O solutions in the dark for at least 24 h at room temperature.

Figure 3.

Structural representations of [Ru(tpy)(L)(py)]2+ (NN = bpy, Me2bpy, biq).

Table 2.

Quantum Yields of Ligand Exchange, ΦLE, and 1O2 production, ΦΔ, for Selected Complexes

| complex | ΦLEa | ΦΔb |

|---|---|---|

| [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ | <10−4 | |

| [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ | 0.16(1) | |

| [Ru(tpy)(biq)(py)]2+ | 0.033(1) | |

| [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ | <10−4 | 0.98(6) |

| [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ | 0.053(1) | 0.69(9) |

CH3CN, λirr = 500 nm.

MeOH, λirr = 460 nm.

The crystal structures reveal key structural distortions in [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(biq)(py)]2+ afforded by steric bulk from the bidentate ligands compared with [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+. In particular, the angle between the plane defined by the bidentate ligand and that of the tpy ligand, determined to be 83.34° in [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+, is reduced to 67.87° and 61.89° in [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(biq)(py)]2+, respectively, similar to distortions reported for related complexes.35,40,41 More importantly, the pyridine ligand in the Me2bpy and biq complexes is distorted relative to that in [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+. The enhanced photoinduced ligand exchange efficiency is correlated to structural distortions, which are believed to stabilize 3LF states and weaken the Ru–py σ bond.

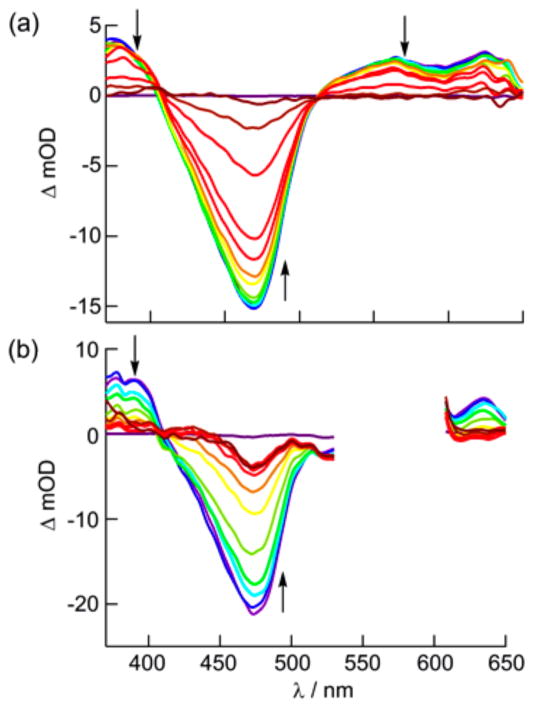

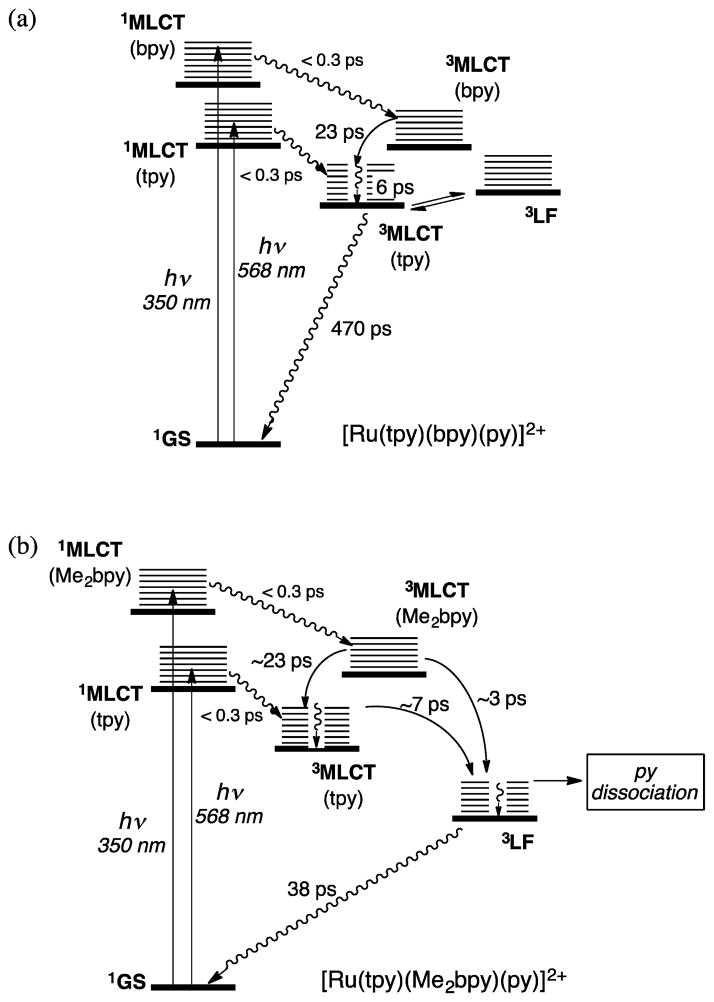

Ultrafast TA spectroscopy reveals the consequences of added steric bulk on the excited-state dynamics of [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)-(py)]2+ compared with [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ (Figure 4). For both complexes, the spectra feature a ground-state bleach centered at ~470 nm as well as positive transient absorption signals at ~375 and >500 nm associated with the Ru(dπ) → tpy(π*) 3MLCT state.42 While the spectral features are similar for the two complexes, stark differences are observed in the kinetics. The absorption changes of the bleach signal at 470 nm for [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ in CH3CN (Figure 4a) can be fitted to a biexponential decay with τ1 = 28 ps (8%) and τ2 = 544 ps (92%). The absorption changes associated with the reduced ligands in the 3MLCT states in the 350–420 nm range display a broad maximum at ~370 nm at 1–10 ps delay but sharpen and red-shift to ~375 nm with a shoulder at ~390 nm at later times. These changes are accompanied by biexponential decays at 375 and 575 nm with τ1 ≈ 3 ps and a long component with τ2 ≈ 500 ps. The Ru → bpy 1MLCT state is preferentially excited at 350 nm, resulting in fast ISC to the corresponding Ru → bpy 3MLCT state with maximum at ~370 nm associated with reduced bpy. This state decays to populate the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state within ~23 ps, with a maximum at ~375 nm and a shoulder at ~410 nm, similar to the spectral features for [Ru(tpy)2]2+.43,44 Since the 28 ps component represents a minor fraction (8%) of the bleach recovery, it corresponds to changes in absorption during 3MLCT(bpy) → 3MLCT(tpy) IC. The 23 ps component for the 3MLCT(bpy) → 3MLCT-(tpy) IC is consistent with the value of 26 ps previously reported for a related complex with two low-lying 3MLCT states.45

Figure 4.

Transient absorption spectra of (a) [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ (λexc = 350 nm) and (b) [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ (λexc = 568 nm) in CH3CN collected 1, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 100, 200, 500, 1000, and 2000 ps following the laser pulse (fwhm = 300 fs, baseline collected at −10 ps).

Excitation of the red edge of the Ru → tpy 1MLCT absorption band of [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ with λexc = 568 nm produces a bleach signal that can be fitted to τ1 = 6 ps (12%) and τ2 = 437 ps (88%); similar kinetics are observed at 375 nm. The 6 ps component is attributed to vibrational relaxation in the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state, which then decays to regenerate the ground state with τ = 470 ps (Figure 5a). As expected, the 23–28 ps component is not present with 568 nm excitation. The 470 ps lifetime of the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state compares well to those of [Ru(tpy)2]2+ (120 ps in CH3CN and 250 ps in H2O).42–44

Figure 5.

Jablonski diagrams for (a) [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ and (b) [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+.

The TA spectra that result from 568 nm excitation of [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ are shown in Figure 4b, where selective population of the Ru → tpy 1MLCT state results in observation of the Ru → tpy 3MLCT absorption signals at ~375 and ~400 nm with monoexponential decay of τ = 6 ps and a biexponential bleach recovery at 470 nm with τ1 = 7 ps (16%) and τ2 = 38 ps (84%). The 6–7 ps component can be ascribed to IC from the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state to populate the 3LF state, which competes with vibrational cooling in the former, and the 3LF state regenerates the ground state with time constant of 38 ps (Figure 5b). Excitation of [Ru(tpy)-(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ at 350 nm provides similar kinetics but with an additional ~3 ps component associated with decay of the Ru → Me2bpy 3MLCT state (Figure 5b). These experiments are consistent with generation of the 3LF state within 3–7 ps, which then deactivates via ligand dissociation and thermal decay to the ground state. It is evident in the ultrafast TA data for [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ in Figure 4b that the ground state does not fully recover in the final trace (2 ns), consistent with formation of the monosubstituted CH3CN photoproduct, [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(CH3CN)]2+. However, the kinetics of the photoproduct formation cannot be determined because of its spectral overlap with the ground and excited states of the starting compound and the relatively small quantity of photoproduct formed.

Distortions around the metal center in [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)-(py)]2+ compared with [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ can explain the differences in excited-state dynamics, resulting in a lower-energy 3LF state in the former that falls below the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state (Figure 5). The lower-energy 3LF state leads to enhanced ligand exchange for the Me2bpy complex; the 3LF lifetime of [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ is similar to those of Ru(II) complexes with sterically bulky ligands, 45 ps for [Ru(6-Mebpy)3]2+ and 7.5 ps for [Ru(Me4bpy)3]2+.25 The formation of a pentacoordinate intermediate (PCI) from the 3LF state is possible, such that the dynamics of the ground-state regeneration are due to geminate recombination of the PCI and pyridine. However, the cage escape and geminate recombination kinetics for the related complex [Ru-(bpy)2(NA)2]2+ (NA = nicotinamide) in water were reported as 377 and 263 ps, respectively.32 This order of magnitude difference between the bleach recovery of [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)-(py)]2+ and [Ru(bpy)2(NA)2]2+ is inconsistent with the 38 ps component assigned as geminate recombination. Ultrafast population of the 3LF state from the Ru → tpy 1MLCT or vibrationally excited 3MLCT state, 3MLCTvΔ1, to afford py dissociation is supported by efficient ligand exchange for [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ with low-energy light (λirr ≥ 600 nm) and the excited-state dynamics measured with 568 nm excitation. This finding is also consistent with the differences in and measured for [Ru(bpy)2(py)2]2+ (Table 1).

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations on [Ru(tpy)-(NN)(py)]2+ (NN = bpy, Me2bpy) show that the unoccupied dx2–y2 orbital, directed along the Ru–py bond, is at a lower energy than the dz2 orbital in each complex. Therefore, population of the lowest-energy LF state results in additional electron density in the dx2–2 orbital, weakening the Ru–py bond. The distortions in [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)(py)]2+ lower the calculated dx2–2 orbital energy by 0.82 eV relative to [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+, consistent with stabilization of the LF states with Ru–py(σ*) character.

DUAL ACTIVITY: PHOTOINDUCED LIGAND EXCHANGE AND 1O2 GENERATION

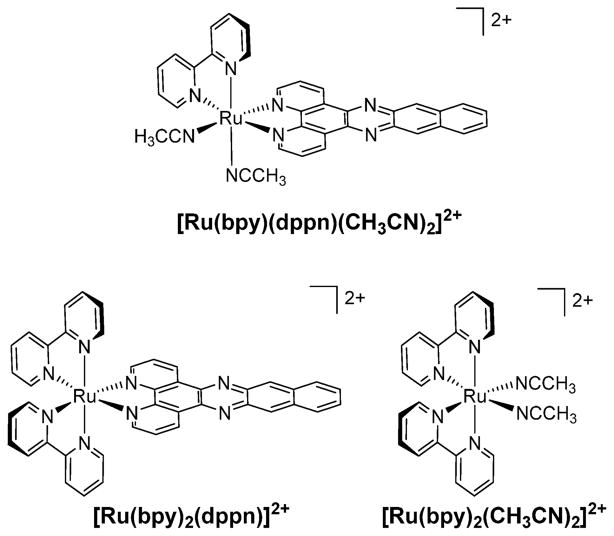

[Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ (dppn = benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) (Figure 6) combines the ligand exchange photochemistry of [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+ and the 1O2 production of [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ to enhance cellular photo-toxicity.46 The electronic absorption spectrum of [Ru(bpy)-(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ features a 1MLCT maximum at 430 nm (11 000 M−1 cm−1) and dppn-centered 1ππ* transitions at 382 nm (11 100 M−1 cm−1) and 405 nm (13 500 M−1 cm−1). The lowest-energy excited state of the complex is the dppn-centered 3ππ* state with τ = 20 μs in CH3CN, similar to those of [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ (τ = 33 μs in CH3CN) and free dppn (τ = 18 μs in CHCl3).21 In [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+, both the lowest-energy 3MLCT excited state (τ = 51 ps) and the low-lying 3LF state are populated upon ultrafast excitation, and the complex undergoes efficient photoinduced ligand exchange.31

Figure 6.

Structural representations of [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+, [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+, and [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+.

Irradiation of [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ in water promotes sequential substitution of the two CH3CN ligands (λirr = 400 nm); the first step forms [Ru(bpy)(dppn)-(CH3CN)(OH2)]2+ with Φ400 = 0.002(3), which is 2 orders of magnitude lower than that in [Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+ (Φ400 = 0.21).31 The quantum yield for production of 1O2 (ΦΔ) from the 3ππ* state of [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ is 0.72(2), which is slightly lower than that of [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ (0.88(2)). The lower yields of ligand exchange and 1O2 generation in [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+ relative to the parent complexes are explained by competitive population of the 3LF and 3ππ* states. A phthalocyanine Ru(II) complex with bound NO ligands was previously shown to produce 1O2 with ΦΔ = 0.29 and photorelease NO.47

Ultrafast TA spectroscopy reveals the excited-state dynamics of [Ru(bpy)(dppn)(CH3CN)2]2+. Because of spectral overlap of the 1MLCT and 1ππ* bands, one cannot be accessed selectively. Excitation in the 300 to 400 nm range results in the observation of both the 3MLCT and 3ππ* states within the laser pulse, with absorption at ~360 and ~540 nm, respectively (Figure 7). Additionally, the lower-lying 3ππ* state is also populated from the 3MLCT state through IC with τ = 22 ps (Figure 7). Although the observed ligand exchange is expected to occur through the 3LF state, the latter was not detected, likely because of its low quantum yield and weak oscillator strength.

Figure 7.

Transient absorption spectra of [Ru(bpy)(dppn)-(CH3CN)2]2+ in CH3CN (λexc = 300 nm, fwhm = 300 fs).

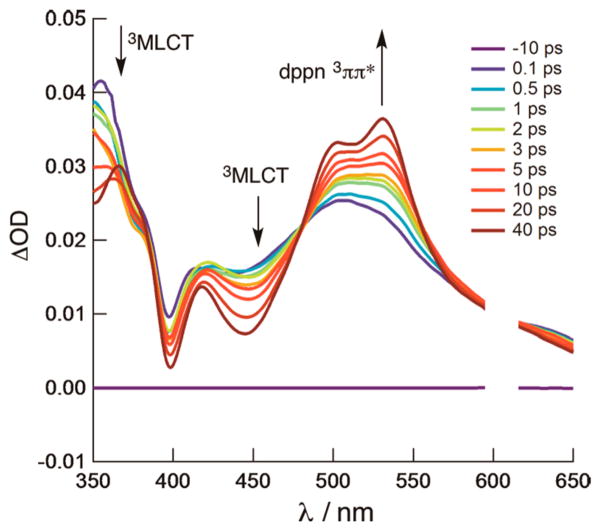

[Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ (Me2dppn = 3,6-dimethylbenzo-[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) (Figure 8) undergoes both pyridine dissociation and 1O2 production with visible light. The Me2dppn ligand causes geometric strain similar to that caused by Me2bpy, but the complex maintains the Me2dppn 3ππ* lowest-energy excited state.48 [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ absorbs strongly in the visible region with dppn-centered 1ππ* transitions at 382 nm (11 400 M−1 cm−1) and 404 nm (12 400 M−1 cm−1) and a 1MLCT peak at 486 nm (12 900 M−1 cm−1). When photolyzed in CH3CN (λirr = 500 nm), [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(CH3CN)]2+ is formed with Φ500 = 0.053(1) in the absence of O2, but ligand exchange is not observed in [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ (Φ500 < 10−4), which lacks steric strain (Table 2). Photosensitization of 1O2 by [Ru(tpy)-(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ occurs with ΦΔ = 0.69(9), which is lower than the value of 0.98(6) measured for [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ (λirr = 460 nm), as listed in Table 2. The reduced quantum yield for [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ can be attributed to competitive deactivation through the 3LF state afforded by distortions around the metal. Competitive population of excited states also explains the lower ligand exchange quantum yield of [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ relative to [Ru(tpy)(Me2bpy)-(py)]2+.

Figure 8.

Structural representations of [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+.

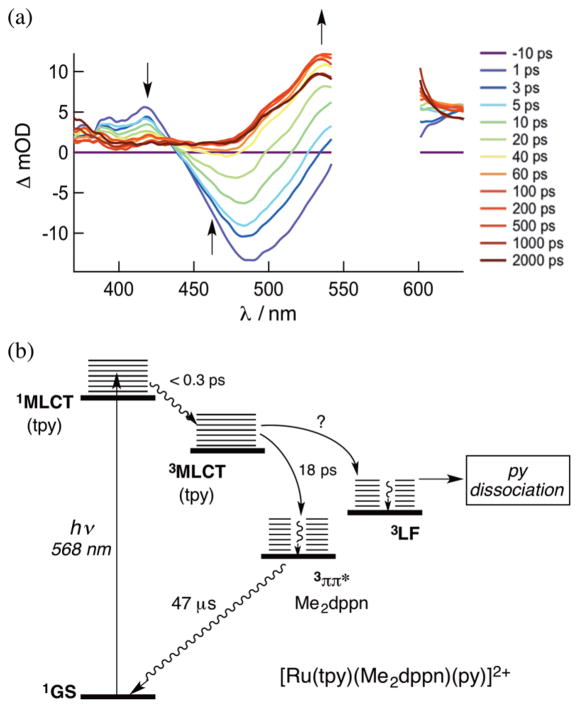

Following selective Ru → tpy 1MLCT excitation of [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ at 568 nm, the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state of [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)-(py)]2+ is observed at ~390 and ~415 nm within the laser pulse, along with a strong ground-state bleach centered at ~480 nm (Figure 9a). Although the signal at 535 nm corresponding to the Me2dppn 3ππ* state is not observed at early times, it evolves with τ1 = 2 ps (28%) and τ2 = 17 ps (72%), concomitant with the decay of the 3MLCT signals fitted to τ1 = 3 ps (13%) and τ2 = 18 ps (87%) at 415 nm and changes in the bleach signal with τ1 = 1 ps (16%) and τ2 = 18 ps (84%). The ~2 ps decay is believed to have contributions from ISC, IC, and vibrational cooling, while the 18 ps component is assigned to population of the 3ππ* state from the 3MLCT state. Similar spectral features and kinetics were measured for [Ru(tpy)-(dppn)(py)]2+ in CH3CN under 568 nm excitation, for which the growth of the 540 nm peak and bleach recovery at 470 nm can be fitted to τ1 = 1 ps (21%) and τ2 = 22 ps (79%). The long component is ascribed to IC from the 3MLCT state to the dppn 3ππ* state, while the short component is related to ISC, IC, and vibrational cooling processes.

Figure 9.

(a) Ultrafast transient absorption of [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)-(py)]2+ in CH3CN (λexc = 568 nm, fwhm = 300 fs) and (b) the corresponding Jablonski diagram.

The Jablonski diagram of [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+, depicted in Figure 9b, shows that IC from the Ru → tpy 3MLCT state to the dppn 3ππ* state occurs with τ = 18 ps in the Me2dppn complex, as opposed to 22 ps in [Ru(tpy)-(dppn)(py)]2+. Since photoinduced ligand exchange is observed in [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ with λirr ≥ 550 nm, low-energy light must populate the dissociative 3LF state. The similarity in the 3ππ* lifetimes of [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(Me2dppn)(py)]2+ (τ = 50 and 47 μs, respectively; λexc = 355 nm, fwhm ≈ 8 ns) is consistent with the 3LF state being located at a higher energy, as shown in Figure 9b.

CONCLUSIONS

The ability of Ru(II) complexes to undergo both photoinduced ligand exchange and 1O2 generation efficiently provides a means to design potentially more active PCT therapeutics. In particular, photorelease of drugs can be coupled to the activity of reactive oxygen species, enabling these compounds to effect cell death via two different mechanisms upon visible-light irradiation. Steric strain can be used to lower the energy of the metal-centered state(s), resulting in greater yields of ligand photodissociation, even when these states(s) are not the lowest in energy. Mixing between the 3LF state(s) and MLCT and/or LC states is believed to play an important role in efficient photoinduced ligand exchange, which is greater when these states are closer in energy. Work is underway to gain further understanding of the coupling between states with the goal of increasing the ligand exchange yields in these dual-action complexes while retaining relatively high sensitization of 1O2 upon irradiation in the photodynamic window (600–900 nm).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Science Foundation (CHE-1465067) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB16072) for partial support and the resources of the Center for Chemical and Biophysical Dynamics (CCBD) at OSU.

Biographies

Jessica D. Knoll received her B.S. in chemistry from the University of Dayton in 2008. In 2013, she earned her Ph.D. from Virginia Tech with Prof. Karen Brewer, and she is currently a postdoctoral researcher with Prof. Claudia Turro at The Ohio State University.

Bryan A. Albani received his B.A. in chemistry from The College of Wooster in 2010. He obtained his Ph.D. in 2015 under the supervision of Prof. Claudia Turro at The Ohio State University and is employed as an Advanced Research Scientist at Owens Corning.

Claudia Turro was born in Argentina and received her B.S. and Ph.D. in chemistry at Michigan State University with Profs. Daniel Nocera and George Leroi. Her graduate work on ultrafast proton-coupled electron transfer and excited states of inorganic complexes was followed by research on the interactions of metal complexes with DNA at Columbia University with Prof. Nicholas Turro as a Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fellow. She began her independent career as a faculty member at The Ohio State University in 1996.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Serpone N, Pelizzetti E, Gratzel M. Photosensitization of Semiconductors with Transition Metal Complexes – A Route to the Photoassisted Cleavage of Water. Coord Chem Rev. 1985;64:225–245. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson DW, Ito A, Meyer TJ. [Ru(bpy)3]2+* and Other Remarkable Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) Excited States. Pure Appl Chem. 2013;85:1257–1305. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Galoppini E, Johansson PG, Meyer GJ. Homoleptic Star-Shaped Ru(II) Complexes. Pure Appl Chem. 2011;83:861–868. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kärkäs MD, Johnston EV, Verho O, Åkermark B. Artificial Photosynthesis: From Nanosecond Electron Transfer to Catalytic Water Oxidation. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:100–111. doi: 10.1021/ar400076j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammarström L. Accumulative Charge Separation for Solar Fuels Production: Coupling Light-Induced Single Electron Transfer to Mulitelectron Catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:840–850. doi: 10.1021/ar500386x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartings MR, Kurnikov IV, Dunn AR, Winkler JR, Gray HB, Ratner MA. Electron Tunneling Through Sensitizer Wires Bound to Proteins. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson BL, Maher AG, Nava M, Lopez N, Cummins CC, Nocera DG. Ultrafast Photoinduced Electron Transfer from Peroxide Dianion. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:7422–7429. doi: 10.1021/jp5110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo KKW, Li SPY. Utilization of the Photophysical and Photochemical Properties of Phosphorescent Transition Metal Complexes in the Development of Photofunctional Cellular Sensors, Imaging Reagents, and Cytotoxic Agents. RSC Adv. 2014;4:10560–10585. [Google Scholar]

- 9.King A, McClure BA, Jin Y, Rack JJ. Investigating the Effects of Solvent on the Ultrafast Dynamics of a Photoreversible Ruthenium Sulfoxide Complex. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118:10425–10432. doi: 10.1021/jp504078g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidmann AG, Komor AC, Barton JK. Targeted Chemotherapy with Metal Complexes. Comments Inorg Chem. 2014;34:114–123. doi: 10.1080/02603594.2014.890099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knoll JD, Turro C. Control and Utilization of Ruthenium and Rhodium Metal Complex Excited States for Photoactivated Cancer Therapy. Coord Chem Rev. 2015;282–283:110–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi T, Gasser G. Towards Tris(diimine)-Ruthenium(II) and Bis(quinoline)-Re(I)(CO)3 Complexes as Photoactivated Anticancer Drug Candidates. Synlett. 2015;26:275–284. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barragan F, Lopez-Senin P, Salassa L, Betanzos-Lara S, Habtemariam A, Moreno V, Sadler PJ, Marchan V. Photo-controlled DNA Binding of a Receptor-Targeted Organometallic Ruthenium(II) Complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14098–14108. doi: 10.1021/ja205235m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford PC. Photochemical delivery of nitric oxide. Nitric Oxide. 2013;34:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howerton BS, Heidary DK, Glazer EC. Strained Ruthenium Complexes Are Potent Light-Activated Anticancer Agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8324–8327. doi: 10.1021/ja3009677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi G, Monro S, Hennigar R, Colpitts J, Fong J, Kasimova K, Yin H, DeCoste R, Spencer C, Chamberlain L, Mandel A, Lilge L, McFarland SA. Ru(II) Dyads Derived from. α-Oligothiphenes: A New Class of Potent and Versatile, Photosensitizers for PDT Coord. Chem Rev. 2015;282–283:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Campagna S, Puntoriero F, Nastasi F, Bergamini G, Balzani V. Photochemistry and Photophysics of Coordination Compounds: Ruthenium. Top Curr Chem. 2007;280:117–214. [Google Scholar]; (b) McCusker JK. Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy of Transition Metal Charge-Transfer Complexes. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:876–887. doi: 10.1021/ar030111d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Juris A, Balzani V, Barigelletti F, Campagna S, Belser P, Von Zelewsky A. Ru(II) Polypyridine Complexes: Photophysics, Photochemistry, Electrochemistry, and Chemiluminescence. Coord Chem Rev. 1988;84:85–277. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kalyanasundaram K. Photophysics, Photochemistry, and Solar Energy Conversion with Tris(bipyridyl)ruthenium(II) and Its Analogues. Coord Chem Rev. 1982;46:159–244. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannizzo A, van Mourik F, Gawelda W, Zgrablic G, Bressler C, Chergui M. Broadband Femtosecond Fluorescence Spectroscopy of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:3174–3176. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhasikuttan AC, Suzuki M, Nakashima S, Okada T. Ultrafast Fluorescence Detection in Tris(2,2′-bipyridine)ruthenium-(II) Complex in Solution: Relaxation Dynamics Involving Higher Excited States. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8398–8405. doi: 10.1021/ja026135h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson NA, Lian T. Ultrafast Electron Injection from Metal Polypyridyl Complexes to Metal-Oxide Nanocrystalline Thin Films. Coord Chem Rev. 2004;248:1231–1246. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Sun Y, Joyce L, Dickson NM, Turro C. Efficient DNA Photocleavage by [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ with Visible Light. Chem Commun. 2010;46:2426. doi: 10.1039/b925574e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu Y, Hammitt R, Lutterman DA, Joyce LE, Thummel RP, Turro C. Ru(II) Complexes of New Tridentate Ligands: Unexpected High Yield of Sensitized 1O2. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:375–385. doi: 10.1021/ic801636u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln R, Kohler L, Monro S, Yin H, Stephenson M, Zong R, Chouai A, Dorsey C, Hennigar R, Thummel RP, McFarland SA. Exploitation of Long-Lived 3IL Excited States for Metal-Organic Photodynamic Therapy: Verification in a Metastatic Melanoma Model. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17161–17175. doi: 10.1021/ja408426z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford WE, Rodgers MAJ. Reversible Triplet-Triplet Energy Transfer within a Covalently Linked Molecule. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:2917–2920. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu J, Chen J, Schmehl RH. Using Intramolecular Energy Transfer to Transform non-Photoactive, Visible-Light-Absorbing Chromophores into Sensitizers for Photoredox Reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7338–7346. doi: 10.1021/ja909785b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun Q, Mosquera-Vazquez S, Daku LML, Guenee L, Goodwin HA, Vauthey E, Hauser A. Experimental Evidence of Ultrafast Quenching of the 3MLCT Luminescence in Ruthenium(II) Tris-bipyridyl Complexes via a 3dd State. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13660–13663. doi: 10.1021/ja407225t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun Q, Mosquera-Vazquez S, Suffren Y, Hankache J, Amstutz N, Daku LML, Vauthey E, Hauser A. On the Role of Ligand-Field States for the Photophysical Properties of Ruthenium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 2015;282–283:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Malouf G, Ford PC. Photochemistry of the Ruthenium-(II) Ammine Complexes, Ru(NH3)5(py-X)2+. Variation of Systemic Parameters to Modify Photochemical Reactivities. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:7213–7221. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tfouni E. Photochemical Reactions of Ammineruthenium(II) Complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;196:281–305. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinnick DV, Durham B. Temperature Dependence of the Quantum Yields for the Photoanation of Ru(bpy)2(L)22+ Complexes. Inorg Chem. 1984;23:3841–3842. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wacholtz WM, Auerbach RA, Schmehl RH, Ollino M, Cherry WR. Correlation of Ligand Field Excited State Energies with Ligand Field Strength in (Polypyridine)ruthenium(II) Complexes. Inorg Chem. 1985;24:1758–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durham B, Caspar JV, Nagle JK, Meyer TJ. Photochemistry of Ru(bpy)32+ J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4803–4810. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sgambellone MA. PhD Dissertation. The Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 2013. Photochemistry and Photophysics of Octahedral Ruthenium Complexes. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Turner DB, Singh TN, Angeles-Boza AM, Chouai A, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Ultrafast Ligand Exchange: Detection of a Pentacoordinate Ru(II) Intermediate and Product Formation. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:26–27. doi: 10.1021/ja806860w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenough SE, Roberts GM, Smith NA, Horbury MD, McKinlay RG, Zurek JM, Paterson MJ, Sadler PJ, Stavros VG. Ultrafast Photo-Induced Ligand Solvolysis of cis-[Ru-(bipyridine)2(nicotinamide)2]2+: Experimental and Theoretical Insight into Its Photoactivation Mechanism. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:19141–19155. doi: 10.1039/c4cp02359e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrauben JN, Dillman KL, Beck WF, McCusker JK. Vibrational Coherence in the Excited State Dynamics of Cr(acac)3: Probing the Reaction Coordinate for Ultrafast Intersystem Crossing. Chem Sci. 2010;1:405–410. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garner RN, Joyce LE, Turro C. Effect of Electronic Structure on the Photoinduced Ligand Exchange of Ru(II) Polypyridine Complexes. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:4384–4391. doi: 10.1021/ic102482c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachter E, Heidary DK, Howerton BS, Parkin S, Glazer EC. Light-Activated Ruthenium Complexes Photobind DNA and are Cytotoxic in the Photodynamic Therapy Window. Chem Commun. 2012;48:9649–9451. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33359g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Zelewsky A, Gremaud G. Ruthenium(II) Complexes with Three Different Diimine Ligands. Helv Chim Acta. 1988;71:1108–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laemmel A-C, Collin J-P, Sauvage J-P. Efficient and Selective Photochemical Labilization of a Given Bidentate Ligand in Mixed Ruthenium(II) Complexes of the Ru(phen)2L2+ and Ru-(bipy)2L2+ Family (L = Sterically Hindering Chelate) Eur J Inorg Chem. 1999:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baranoff E, Collin J, Furusho J, Furusho Y, Laemmel A, Sauvage J. Photochemical or Thermal Chelate Exchange in the Ruthenium Coordination Sphere of Complexes of the Ru(phen)2L Family (L = Diimine or Dinitrile Ligands) Inorg Chem. 2002;41:1215–1222. doi: 10.1021/ic011014o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knoll JD, Albani BA, Durr CB, Turro C. Unusually Efficient Pyridine Photodissociaition from Ru(II) Complexes with Sterically Bulky Bidentate Ancillary Ligands. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118:10603–10610. doi: 10.1021/jp5057732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wachter E, Howerton BS, Hall EC, Parkin S, Glazer EC. A New Type of DNA “Light-Switch”: A Dual Photochemical Sensor and Metalating Agent for Duplex and G-Quadruplex DNA. Chem Commun. 2014;50:311–313. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47269h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonnet S, Collin JP, Sauvage JP, Schofield E. Photo-chemical Expulsion of the Neutral Monodentate Ligand L in Ru(Terpy*)(Diimine)(L)2+: A Dramatic Effect of the Steric Properties of the Spectator Diimine Ligand. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:8346–8354. doi: 10.1021/ic0491736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winkler JR, Netzel TL, Creutz C, Sutin N. Direct Observation of Metal-to-ligand Charge-Transfer (MLCT) Excited States of Pentaammineruthenium(II) Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2381–2392. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siemeling U, Vor der Bruggen J, Vorfeld U, Neumann B, Stammler A, Stammler H, Brockhinke A, Plessow R, Zanello P, Laschi F, de Biani FF, Fontani M, Steenken S, Stapper M, Gurzadyan G. Ferrocenyl-Functionalised Terpyridines and Their Transition-Metal Complexes: Syntheses, Structures and Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Properties. Chem - Eur J. 2003;9:2819–2833. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Hammitt R, Lutterman DA, Thummel RP, Turro C. Marked Differences in Light-Switch Behavior of Ru(II) Complexes Possessing a Tridentate DNA Intercalating Ligand. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:6011–6021. doi: 10.1021/ic700484j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Y, Liu Y, Turro C. Ultrafast Dynamics of the Low-Lying 3MLCT States of [Ru(bpy)2(dppp2)]2+ J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5594–5595. doi: 10.1021/ja101703w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albani BA, Peña B, Leed NA, de Paula NABG, Pavani C, Baptista MS, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Marked Improvement in Photoinduced Cell Death by a New Tris-heteroleptic Complex with Dual Action: Singlet Oxygen Sensitization and Ligand Dissociation. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:17095–17101. doi: 10.1021/ja508272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carneiro ZA, de Moraes JCB, Rodrigues FP, de Lima RG, Curti C, da Rocha ZN, Paulo M, Bendhack LM, Tedesco AC, Formiga ALB, da Silva RS. Photocytotoxic activity of a nitrosyl phthalocyanine ruthenium complex – A system capable of producing nitric oxide and singlet oxygen. J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knoll JD, Albani BA, Turro C. Excited State Investigation of a New Ru(II) Complex for Dual Reactivity with Low Energy Light. Chem Commun. 2015;51:8777–8780. doi: 10.1039/c5cc01865j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]