Abstract

BACKGROUND

Intraoperative awareness with explicit recall is a potentially devastating complication of surgery that has been attributed to low anaesthetic concentrations in the vast majority of cases. Past studies have proposed the determination of an adequate dose for general anaesthetics that could be used to alert providers of potentially insufficient anaesthesia. However, there have been no systematic analyses of appropriate thresholds to develop population-based alerting algorithms for preventing intraoperative awareness.

OBJECTIVE

To identify a threshold for intraoperative alerting that could be applied for the prevention of awareness with explicit recall.

DESIGN

Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial (Michigan Awareness Control Study).

SETTING

Three hospitals at a tertiary care centre in the USA.

PATIENTS

Unselected patients presenting for surgery under general anaesthesia.

INTERVENTIONS

Alerts based on end-tidal anaesthetic concentration or Bispectral Index values.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Using case and outcomes data from the primary study, end-tidal anaesthetic concentration and Bispectral Index values were analysed using Youden’s index and c-statistics derived from a receiver operating characteristic curve to determine a specific alerting threshold for the prevention of awareness.

RESULTS

No single population-based threshold that maximises sensitivity and specificity could be identified for the prevention of intraoperative awareness, using either anaesthetic concentration or Bispectral Index values. The c-statistic for anaesthetic concentration was 0.431 ± 0.046, and 0.491 ± 0.056 for Bispectral Index values.

CONCLUSIONS

We could not derive a single population-based alerting threshold for the prevention of intraoperative awareness using either anaesthetic concentration or Bispectral Index values. These data indicate a need to move towards individualised alerting strategies in the prevention of intraoperative awareness.

Introduction

Intraoperative awareness with explicit recall (AWR) of surgical events can be a devastating complication for patients, with significant psychological sequelae.1–6 The incidence of definite AWR in patients undergoing general anaesthesia is reported to be between 1–2/1,000 cases and as high as 3–4/1,000 cases for both possible and definite AWR events;7–9 in patients at high risk for AWR, the incidence approaches 1%.10 It has been posited that the primary aetiology of AWR is insufficient anaesthesia (rather than, for example, genetic factors),5,11 suggesting that alerting protocols could prevent AWR if a specific threshold was identified.

Two common surrogates for anaesthetic depth are minimum alveolar concentration (MAC), measured by end-tidal anaesthetic concentration (ETAC), and the Bispectral Index® (BIS). Alerting algorithms based on either MAC or BIS values can be implemented easily to notify the provider of potentially insufficient anaesthesia. The rapid expansion of electronic Anaesthesia Information Systems (AIMS) allows for enhanced use of alerting algorithms with the potential to combine demographic, co-morbidity, physiological and anaesthetic concentration variables. In addition, the AIMS allow the provider to be notified via pager for potentially insufficient anaesthesia even when the alarms on the primary monitoring system have been silenced.

Clinical trials investigating the prevention of AWR9,10,12–14 used specific thresholds for potentially insufficient anaesthesia, with the provider being instructed to keep the BIS value between 40 and 60 or with audible alarms if the BIS or MAC values fell outside defined ranges. The MAC and BIS values chosen were based on previously published work, but to date there has been no systematic study of the appropriate threshold for MAC or BIS alarms for the prevention of AWR based on prospectively collected data.

The parent trial for this study9 investigated whether the use of alerting algorithms in cases randomised to either anaesthetic concentration or BIS values decreased the incidence of AWR. It did not investigate discrete MAC or BIS data elements to determine if there is a specific value that would maximise sensitivity and specificity in the prevention of AWR or explore any changes in provider behaviour when alerts are generated. Therefore, the objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that there is an evidence-based alerting threshold for MAC or BIS values that would maximise the sensitivity and specificity of alarms aimed at preventing AWR. In addition, we sought to determine if alerting the provider changes behaviour with respect to anaesthetic management in the prevention of AWR.

Methods

This study is a pre-specified secondary analysis of the Michigan Awareness Control Study (MACS) (ClinicalTrials.gov No. NCT00689091).9 The parent trial and this secondary analysis were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB HUM 13626, initial study approval 14 August 2007) of the University of Michigan (2800 Plymouth Road, Building 520 Room 3214, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; Chairs, Drs Michael Geisser and John Weg). In brief, we screened all adult patients between May 2008 and May 2010 presenting to a multihospital healthcare system for surgery with general anaesthesia using an inhaled or intravenous anaesthetic. A detailed discussion with each patient took place and verbal informed consent was obtained and documented in our AIMS. Patients were excluded if the use of a BIS monitor was impractical (e.g. intracranial procedures, adhesive allergy, surgery involving the forehead) or an underlying brain disorder rendered the BIS a questionable measure of consciousness (e.g. history of traumatic brain injury). The BIS Quatro sensor (Covidien, Boulder, CO, USA) was attached preoperatively in all patients by a member of the research staff. Alerts to notify the provider of potentially insufficient anaesthetic dosing were based on either the age-adjusted MAC (aaMAC)15 or BIS values. For the parent trial, aaMAC was calculated based on pre-specified age groups.16

A detailed description of the randomisation and blinding is explained elsewhere9,17 and is briefly summarised here. The study was divided into year quarters (eight 3-month periods over 2 years), with MAC and BIS alerting algorithms assigned randomly for each quarter. For the MAC alerting rooms, the real-time BIS values were hidden from the provider’s view. In addition, if the median ETAC for a 5-min epoch was less than 0.5 aaMAC, an alphanumeric paging alert was generated to the provider in the room. For the BIS alerting group, the BIS values were visible to the provider. In addition, if the median BIS value for a 5-min epoch was greater than 60, an alphanumeric paging alert was generated. A study team member contacted each patient and administered the modified Brice interview 28–30 days after surgery.18,19 As described previously,9 after the modified Brice interview and additional interviews of potential AWR patients were performed, each event was categorised as no AWR, possible AWR or definite AWR. Data from other trials in which the authors were involved12,13 could not be included due to differences in data acquisition systems and incomplete records of alarm delivery.

For the MACS trial, Centricity® (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA) was the AIMS used for programming alerts and notifying providers via alphanumeric text paging. Centricity interfaces with the haemodynamic monitors (GE Marquette Solar 9500, Milwaukee, WI) and also with the anaesthesia machine (AISYS Anaesthesia Machine, GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA). ETAC values were automatically calculated in real time from the expired volatile anaesthetic concentrations that were collected by the AISYS anaesthesia machine and transmitted to Centricity. BIS and ETAC data elements were electronically captured for every patient by the AIMS every 60 s and were available for later study extraction and analysis.

For this secondary analysis, we included cases in which inhaled volatile agents were used as the primary anaesthetic. We excluded total intravenous anaesthetic (TIVA) cases, any case for which a propofol infusion was used in conjunction with a volatile anaesthetic and any case with missing volatile anaesthetic data due to infrequent AIMS data interface issues.

Secondary analysis methodology

All cases were reviewed to ensure complete data for ETAC and BIS values from an electronically documented time of ‘anaesthesia induction end’ to the time of ‘request for post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) bed’ or ‘transport to the intensive care unit.’ For this secondary analysis, aaMAC was calculated based on the age documented in the AIMS at the time of operation and not on the pre-specified age groups as in the parent trial.15 The surgery was divided into 5-min epochs (during the AIMS timestamps listed previously) and the median ETAC was calculated for each of those 5-min epochs. The overall median ETAC was also calculated for each case. The same technique was used for patients with valid BIS monitoring data.

Data were analysed using two different methods to determine a single threshold for the prevention of AWR for ETAC and BIS values. First, the data were dichotomised by whether any 5-min epoch was below (aaMAC) or above (BIS) a set value throughout the case. The maximum sensitivity, specificity and Youden’s index were calculated. Second, the median ETAC and BIS values for the case were analysed using a receiver operating characteristic curve c-statistic. If the c-statistic demonstrated adequate discriminating capacity (> 0.70), then the value with the maximum sensitivity and specificity would be computed and retrospectively applied to the database to determine a single threshold for the prevention of AWR.

To investigate whether the alerting algorithm changed provider behaviour, we first calculated the percentage of the case during which the anaesthetic concentrations triggered the alarm. This percentage was calculated by dividing the number of 5-min epochs that met the ETAC alerting threshold by the number of 5-min epochs overall. We chose to present the data as the percentage of the case duration instead of total minutes of the case to account for the variance in length of procedures. A control group that had no real-time alerting interventions, distinct from the ETAC and BIS groups, was used to explore whether there is a behavioural effect by retrospectively applying the ETAC alerting algorithm. This group received neither BIS nor MAC alerts yet was still assessed for AWR; the anaesthetic was delivered based on routine clinical and haemodynamic variables. The control group resulted from technical interface issues from the parent trial and was not pre-specified.9 However, since there was a ‘no intervention’ group that resulted from MACS, we could assess whether there was a behavioural effect attributable to having alerts generated throughout the case. This was accomplished by retrospectively applying the ETAC alerting algorithm to the ‘no intervention’ group and calculating what percentage of time the case would have triggered an alarm if an algorithm had actually been active in real time. The percentage of the case during which the anaesthetic triggered the ETAC alerting algorithm was then compared between the original ETAC intervention arm and the post hoc control group. The mean percentage of the case that triggered an alarm was also examined for change in behaviour across the study period for both the ETAC and BIS arms. If the mean percentage changed across the quarters, this would indicate that anaesthetic delivery behaviour had changed.

Statistical analysis

Due to the low incidence of definite AWR in the parent trial and the potential psychological impact of possible AWR, we combined definite and possible AWR events into one category for this secondary analysis. To determine if there was a single threshold that maximises sensitivity and specificity for the prevention of AWR, aaMAC for all cases was dichotomised by whether the case did or did not have any 5-min median epochs in which the aaMAC was < 0.4, < 0.5, < 0.6, < 0.7, < 0.8 or < 0.9. The same dichotomising technique was used for cases with valid BIS data that had at least one 5-min median epoch with BIS > 60, > 70, > 80 or > 90. The baseline BIS threshold was set at 60 because this generally represents the threshold between general anaesthesia (< 60) and sedation or wakefulness (> 60).20 Sensitivity, specificity and Youden’s index were then calculated to determine if there was an optimal threshold for the prevention of AWR for either aaMAC or BIS. The Youden’s index was calculated as (sensitivity + specificity – 1).21 A Youden’s index of 1 would indicate that the threshold is perfect and a Youden’s index of 0 would indicate that the threshold has no diagnostic value in the prevention of AWR.21 Next, a c-statistic was calculated from a receiver operating characteristic curve to determine if there was a single diagnostic threshold for either ETAC or BIS that can be quantified for prevention of AWR. If the c-statistic was deemed adequate (> 0.70), then the continuous data for both aaMAC and BIS would be analysed to determine the specific threshold in the prevention of AWR.

A Mann-Whitney U-test was performed to assess whether providers receiving the original MAC alerts differed statistically when compared to the ‘no intervention’ (i.e. no alert) group for the entire time period and by quarter of the study. To determine if there was a behavioural change, as documented by a significant difference in the percentage of the case that triggered an alert for potentially insufficient anaesthesia, a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed for both MAC and BIS arms across the study period. Data are displayed as the mean percentage of the case to trigger an alert ± 2 × SEM.

SPSS® version 20 (IBM® Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses. Data extraction from AIMS was completed using SQL. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout.

Results

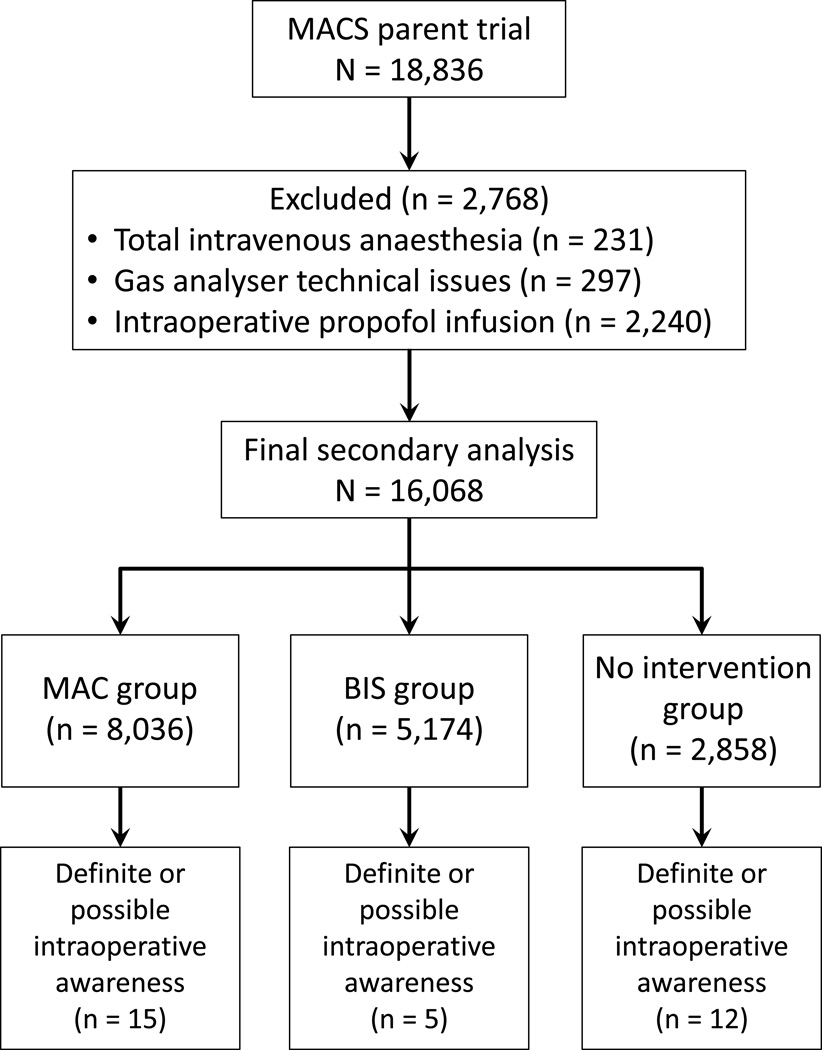

The parent trial had a total of 18,836 patients with complete information on the AWR outcome. We excluded 231 cases because of the use of TIVA, 297 for agent analyser device technical issues and 2,240 for use of an adjunct intraoperative propofol infusion. This resulted in a dataset of 16,068 patients, with a total of 32 definite or possible AWR events (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram. Parent trial to secondary analysis with outcome of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall (AWR).

MACS, Michigan Awareness Control Study; MAC minimum alveolar concentration; BIS, Bispectral Index.

Youden’s index did not demonstrate a single threshold for aaMAC or BIS values in the prevention of AWR (Table 1). The c-statistic for median aaMAC was 0.431 ± 0.046 and 0.491 ± 0.056 for BIS indicating that there is not a specific threshold that can be calculated for the prevention of AWR when using either aaMAC or BIS values. There were 10 patients who experienced an AWR event with BIS values < 60 (median for 5-min epoch) for the entire case.

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, and Youden’s index for cases that had valid measurements for end-tidal anaesthetic concentration and Bispectral Index values

| aaMAC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Youden’s index | |

| aaMAC < 0.4 | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.47) | 0.79 (0.79 to 0.79) | 0.07 ( to 0.06 – 0.26) |

| aaMAC < 0.5 | 0.38 (0.22 to 0.56) | 0.71 (0.71 to 0.71) | 0.08 (−0.08 to 0.27) |

| aaMAC < 0.6 | 0.44 (0.27 to 0.62) | 0.59 (0.59 to 0.60) | 0.03 (−0.14 to 0.24) |

| aaMAC < 0.7 | 0.59 (0.41 to 0.76) | 0.45 (0.45 to 0.45) | 0.05 (−0.14 to 0.21) |

| aaMAC < 0.8 | 0.78 (0.60 to 0.90) | 0.30 (0.30 to 0.30) | 0.08 (−0.10 to 0.20) |

| aaMAC < 0.9 | 0.81 (0.63 to 0.92) | 0.18 (0.18 to 0.18) | −0.01 (−0.19 to 0.10) |

| BIS | |||

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Youden’s Index | |

| BIS ≥ 60 | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.43) | 0.72 (0.72 to 0.72) | −0.19(−0.28 to 0.15) |

| BIS ≥ 70 | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.32) | 0.91 (0.91 to 0.91) | −0.09 (−0.09 to 0.24) |

| BIS ≥ 80 | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.32) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.97) | −0.03 (−0.03 to 0.29) |

| BIS ≥ 90 | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.31) | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.31) |

aaMAC, age-adjusted MAC; BIS, Bispectral Index

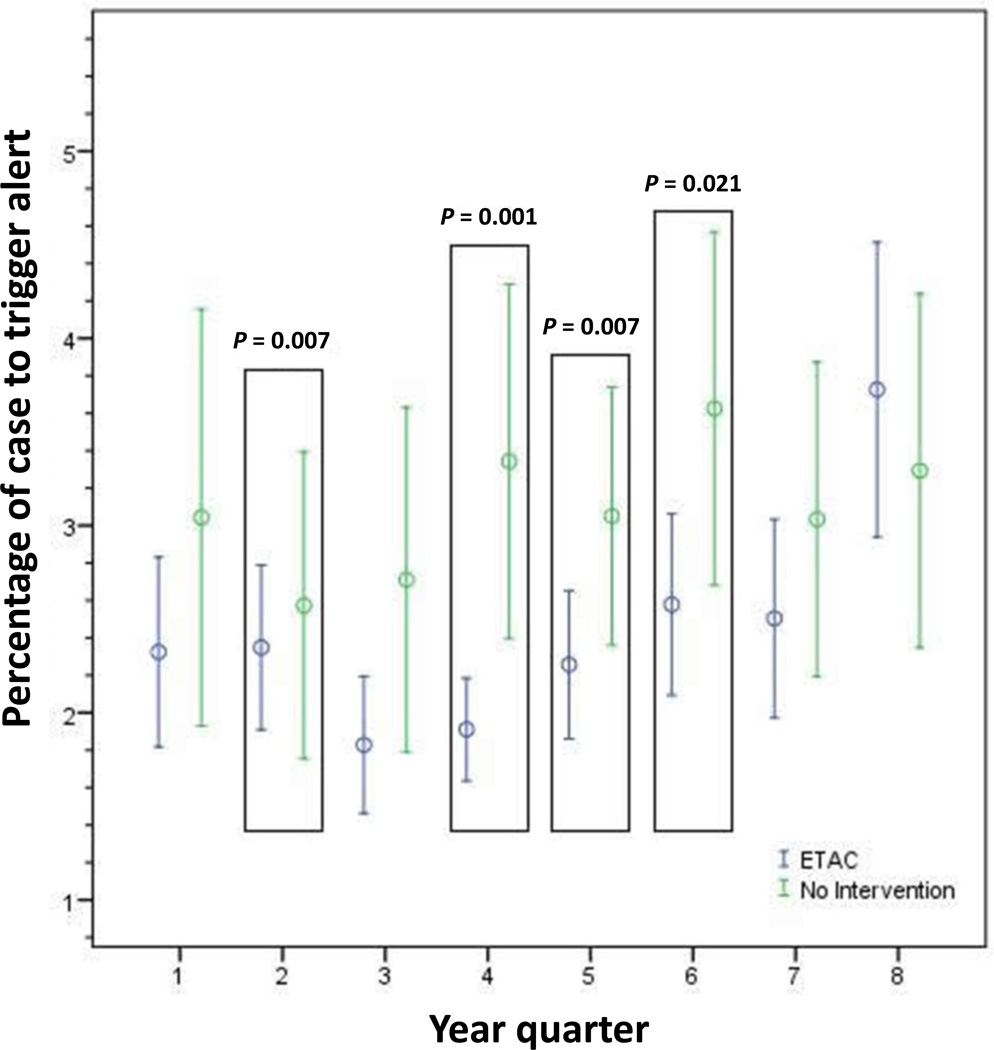

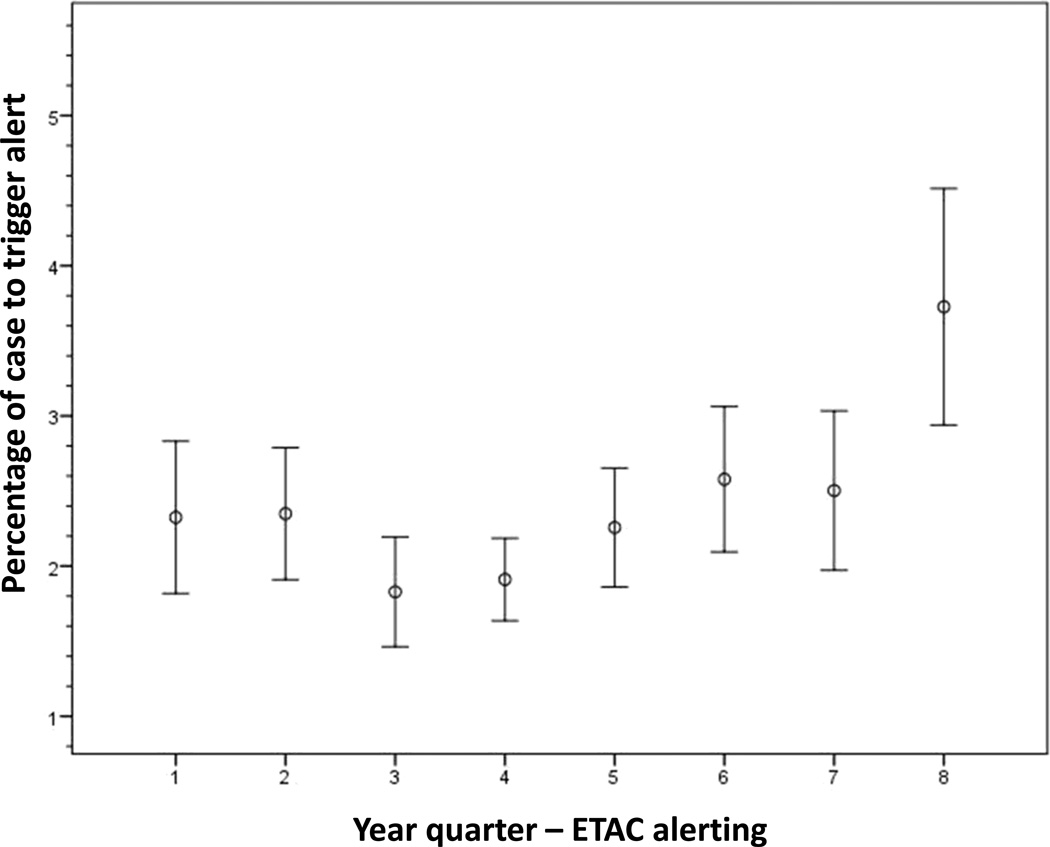

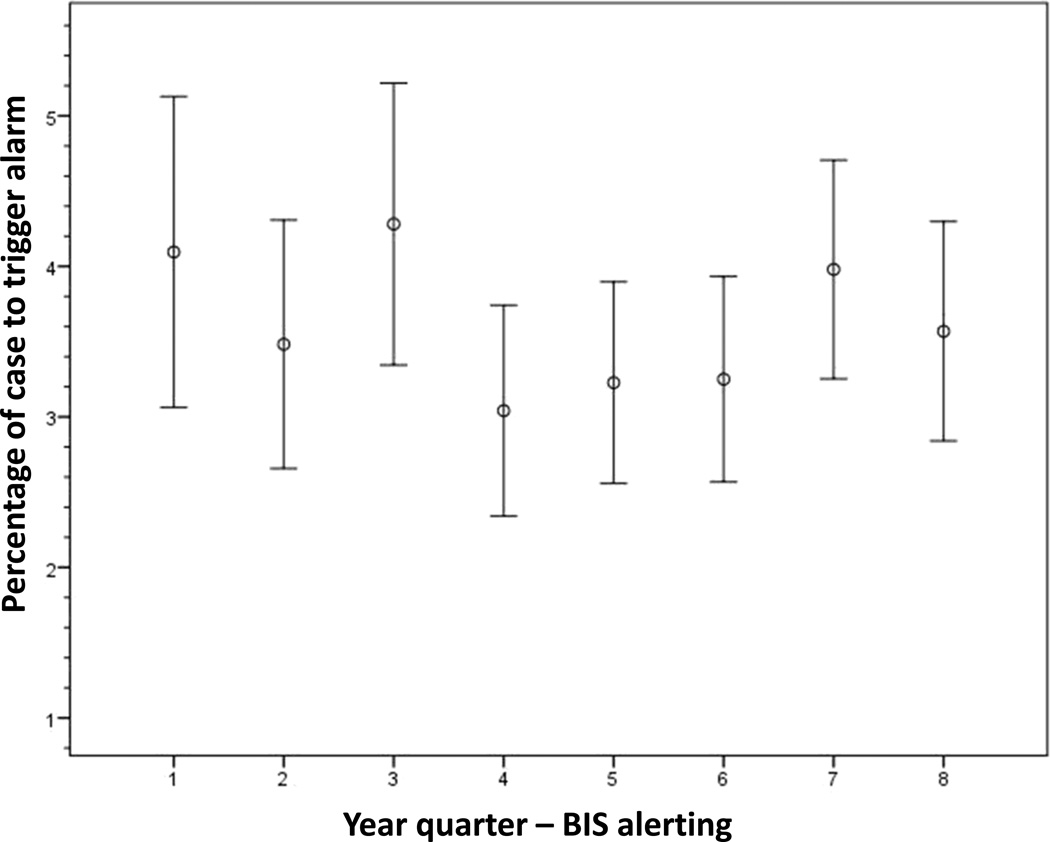

When applying the ETAC alerting algorithm retrospectively to the ‘no intervention’ (i.e. no alert) cases, we determined that cases randomised to MAC alerting had a statistically shorter mean percentage of the case that generated an alert for potentially insufficient anaesthesia than the ‘no intervention’ cases (2.4% ± 7.5% vs. 3.1% ± 8.5%, P = 0.009). Four of the eight year quarters demonstrated these findings while the remaining quarters did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2). In the trend analysis by study period, the mean percentage of the case that triggered a potentially insufficient anaesthetic alert in the ETAC arm increased significantly (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). However, the mean percentage of the case that generated a BIS alert via the alerting algorithm did not change across the study period (P = 0.38) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Comparison of end-tidal anaesthetic concentration (ETAC) alerting and ‘no intervention’ group behaviour.

Figure shows plot depicting the mean percentage of the case to trigger an alert ± 2 × SEM. Quarter refers to the eight 3-month periods over 2 years.

Fig. 3. End-tidal anaesthetic concentration (ETAC) alerting trend analysis.

Figure shows plot depicting the mean percentage of the case to trigger an alert ± 2 × SEM.

Fig. 4. Bispectral Index (BIS) alerting trend analysis.

Figure shows plot depicting the mean percentage of the case to trigger an alert ± 2 × SEM.

Discussion

Population-based alerting in the prevention of AWR is important to consider because retrospective evidence shows that approximately 87% of all AWR cases are attributable to insufficient anaesthesia.5 An editorial by Nickalls and Mahajan11 presented a parsimonious approach by stating that all cases of AWR are attributable to insufficient anaesthesia unless there is compelling evidence to the contrary. They suggested that a population-based adequate dose for anaesthetics should be identified and implemented for the prevention of AWR.11 In the present study, we analysed discrete surrogate metrics of anaesthetic depth (ETAC and BIS) in order to identify a single diagnostic threshold for the systematic prevention of AWR. We have demonstrated that, in patients undergoing general anaesthesia in which only volatile anaesthetics were used, there is no population-based threshold that could be used as an alert in the prevention of definite or possible AWR using either ETAC or BIS. The population data from Youden’s index suggest that the thresholds studied would not result in the eradication of AWR.

The thresholds that we selected in the current study were representative of what would be considered standard of care aaMAC for patients under general anaesthesia. Concentrations higher than 1.0 aaMAC were excluded from this analysis because of very high false positive alarms at thresholds of ≥ 0.7 MAC.16 It is important to note that Youden’s index incorporates data on both sensitivity and specificity. As Table 1 indicates, lower alerting thresholds (e.g. higher anaesthetic concentrations) increase sensitivity at the cost of decreasing specificity. Thus, including thresholds of AWR alerting beyond 1 MAC would further increase sensitivity, but would probably not increase Youden’s index due to the concomitant decrease in specificity. In addition, the c-statistics indicated that, for both aaMAC and BIS, there was approximately a 50% chance (essentially random) of determining the correct threshold in the prevention of AWR using a population-based approach.21

To date, multiple randomised controlled trials have been conducted using a population-based alerting (or monitoring) strategy in which a specific alarm or range for ETAC or BIS was established for the prevention of AWR.9,10,12,13,22 Myles et al.10 found that BIS monitoring (maintained between 40 and 60) was associated with a relative risk reduction of 82% in surgical patients at high risk for AWR when compared to routine monitoring. The next two trials used audible alerts to notify the provider of potentially insufficient anaesthesia in patients at high risk of AWR. Avidan et al.12,13 found that both BIS and ETAC alarms reduced observed awareness events compared to the expected incidence. Mashour et al.9 included unselected surgical patients requiring general anaesthesia and demonstrated that BIS alerting protocols reduced the incidence of definite or possible AWR compared to no intervention. The persistence of AWR in previous trials suggests that population-based alerting approaches for insufficient anaesthesia will not eradicate AWR. The current study adds to the literature by suggesting that it was not simply the empirical or arbitrary determination of alerting thresholds in past trials that failed to eradicate AWR because our systematic analysis and comparison suggest that no one threshold exists. Rather than arguing that BIS or ETAC alerts are not useful, we would instead encourage clinicians to choose some threshold to prevent egregious aetiologies of AWR (such as an empty vaporiser). Past randomised controlled trials demonstrate that alerts are, in fact, associated with reduced AWR.

At an individual level, we know that there is a specific threshold at which a given patient will be likely to experience AWR. The identification of such a threshold will, in the future, probably be guided by risk factors for AWR coupled with more sophisticated monitoring. Previous work has reported specific patient-based risk factors for AWR.5 Further identification of risk factors, in conjunction with developments in monitoring the neural substrates of consciousness, must ultimately be incorporated into prevention strategies for AWR at an individualised level.

Fundamentally, individualised alerting strategies would not be beneficial without establishing evidence that real-time alarms are capable of changing behaviour. We have demonstrated that real-time alerting alters the administration of anaesthetics. When retrospectively applying the MAC alerting algorithm to the ‘no intervention’ cases in the parent trial, the providers who were not alerted to potentially insufficient anaesthesia had lower MAC values throughout the case than those who were alerted in real time. This indicates that the providers receiving alerts were statistically more likely to keep the anaesthetic concentration within the stated range for the trial and, we infer, changed their behaviour to do so. These results confirm other previously published studies that providing clinicians with alerts can drive a change in clinical care.23–30

When alerting is used to notify providers to change behaviour, there is the potential for alert fatigue, which is defined as the provider becoming less responsive due to an alarm becoming bothersome or ineffective. Alert fatigue is an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in the medical community, especially with the rapid advancement of electronic medical records.31–33 Block et al.34 surveyed anaesthesiologists practising in the USA and found that 70% of the times that alarms were silenced were due to the perception of a false alarm. Only 16% of providers stated that they never turn off alarms.34 Therefore, it is imperative to minimise false alarms – and, consequently, alert fatigue – in developing an alerting strategy for AWR, a difficult task given the rarity of the outcome. This is one reason why the current study focused on both sensitivity and specificity. We found evidence of alert fatigue as well as possible desensitisation to ETAC alerts across the study period. The mean percentage of the case that generated an ETAC alert changed significantly during the last quarter of the trial, with alerts having increased approximately 1.2% from the previous quarter and 1.5% from the beginning of the study. These data could indicate that the providers thought the alerts were false alarms and therefore were becoming desensitised and fatigued as the study continued (delayed alert fatigue). However, these findings were only found in the last quarter of the study and could also be an outlier. The BIS alerting rate was consistent throughout the study and showed no evidence of generating desensitisation or alert fatigue.

The main limitation of this study was the small number of AWR outcomes in our population (n = 32). To move towards an individualised alerting approach, a multinomial logistic regression model must be developed that incorporates patient-specific risk factors (such as history of AWR)35 along with anaesthetic concentrations and, if possible, neurophysiological indices. Furthermore, we used the median from a 5-min period and must acknowledge that the individual BIS or MAC values could have nonetheless fluctuated in a way that might not be detected with our methodology. Finally, the current study only investigated a threshold using general anaesthesia with inhaled anaesthetics and is thereby not generalisable to cases performed using TIVA.

In conclusion, we could not identify a single practical threshold of ETAC or BIS values that can be chosen for the eradication of definite and possible AWR in a broad surgical population. Although alerts have been demonstrated to prevent AWR, future work must move towards an individualised patient-based approach incorporating specific risk factors as well as monitoring the neural substrates of consciousness. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated promise in identifying correlates of anaesthetic-induced unconsciousness based on the neurobiology of consciousness.36,37 Finally, we were able to demonstrate that providing alerts via an AIMS can influence intraoperative care but ETAC alerting has the potential for desensitisation and alert fatigue.

Acknowledgments

Assistance with the study: none.

Financial support: the parent trial, entitled Prevention of intraoperative awareness in an unselected surgical population: a randomized compared effectiveness trial, was funded by the Cerebral Function Monitoring grant (to G.A.M.) from the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (Rochester, MN, USA)/American Society of Anesthesiologists (Park Ridge, IL, USA); the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) (KL2 RR024987-01) (to G.A.M.); Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Medical School. This secondary analysis was funded by the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Medical School.

Footnotes

Trial registration: Primary trial registration (Michigan Awareness Control Study) ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00689091.

Conflicts of interest: G.A.M. has a patent pending (through the University of Michigan) on the use of connectivity measures to assess levels of consciousness.

Presentation: some results of this study were presented at the annual meeting of the International Anesthesia Research Society in San Diego, CA, USA, 2013.

Contributor Information

Amy M. Shanks, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Michael S. Avidan, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

Sachin Kheterpal, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Kevin K. Tremper, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

John C Vandervest, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

John M. Cavanaugh, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA

George A. Mashour, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

References

- 1.Moerman N, Bonke B, Oosting J. Awareness and recall during general anesthesia. Facts and feelings. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:454–464. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwender D, Kunze-Kronawitter H, Dietrich P, Klasing S, Forst H, Madler C. Conscious awareness during general anaesthesia: patients' perceptions, emotions, cognition and reactions. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:133–139. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domino KB, Posner KL, Caplan RA, Cheney FW. Awareness during anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1053–1061. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199904000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osterman JE, Hopper J, Heran WJ, Keane TM, van der Kolk BA. Awareness under anesthesia and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:198–204. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghoneim MM, Block RI, Haffarnan M, Mathews MJ. Awareness during anesthesia: risk factors, causes and sequelae: a review of reported cases in the literature. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:527–535. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318193c634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leslie K, Chan MT, Myles PS, Forbes A, McCulloch TJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in aware patients from the B-aware trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:823–828. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b8b6ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandin RH, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Lennmarken C. Awareness during anaesthesia: a prospective case study. Lancet. 2000;355:707–711. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)11010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sebel PS, Bowdle TA, Ghoneim MM, et al. The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States study. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:833–839. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000130261.90896.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mashour GA, Shanks A, Tremper KK, et al. Prevention of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall in an unselected surgical population: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:717–725. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826904a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, Forbes A, Chan MT. Bispectral index monitoring to prevent awareness during anaesthesia: the B-Aware randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1757–1763. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nickalls RW, Mahajan RP. Awareness and anaesthesia: think dose, think data. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:1–2. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1097–1108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avidan MS, Jacobsohn E, Glick D, et al. Prevention of intraoperative awareness in a high-risk surgical population. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:591–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Xu L, Ma YQ, et al. Bispectral index monitoring prevent awareness during total intravenous anesthesia: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, multi-center controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124:3664–3669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickalls RW, Mapleson WW. Age-related iso-MAC charts for isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane in man. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:170–174. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashour GA, Esaki RK, Vandervest JC, Shanks A, Kheterpal S. A novel electronic algorithm for detecting potentially insufficient anesthesia: implications for the prevention of intraoperative awareness. J Clin Monit Comput. 2009;23:273–277. doi: 10.1007/s10877-009-9193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mashour GA, Tremper KK, Avidan MS. Protocol for the ‘Michigan Awareness Control Study’: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing electronic alerts based on bispectral index monitoring or minimum alveolar concentration for the prevention of intraoperative awareness. BMC Anesthesiol. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brice DD, Hetherington RR, Utting JE. A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1970;42:535–542. doi: 10.1093/bja/42.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abouleish E, Taylor FH. Effect of morphine-diazepam on signs of anesthesia, awareness, and dreams of patients under N2O for cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1976;55:702–705. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass PS, Bloom M, Kearse L, Rosow C, Sebel P, Manberg P. Bispectral analysis measures sedation and memory effects of propofol, midazolam, isoflurane, and alfentanil in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:836–847. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 13: receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care. 2004;8:508–512. doi: 10.1186/cc3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avidan MS, Mashour GA. Prevention of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall: making sense of the evidence. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:449–456. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827ddd2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bates DW, Cohen M, Leape LL, Overhage JM, Shabot MM, Sheridan T. Reducing the frequency of errors in medicine using information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8:299–308. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2001.0080299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St Jacques P, Sanders N, Patel N, Talbot TR, Deshpande JK, Higgins M. Improving timely surgical antibiotic prophylaxis redosing administration using computerized record prompts. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2005;6:215–221. doi: 10.1089/sur.2005.6.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:969–977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Reilly M, Talsma A, VanRiper S, Kheterpal S, Burney R. An anesthesia information system designed to provide physician-specific feedback improves timely administration of prophylactic antibiotics. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:908–912. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000237272.77090.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kheterpal S, Gupta R, Blum JM, Tremper KK, O'Reilly M, Kazanjian PE. Electronic reminders improve procedure documentation compliance and professional fee reimbursement. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:592–597. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255707.98268.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wax DB, Beilin Y, Levin M, Chadha N, Krol M, Reich DL. The effect of an interactive visual reminder in an anesthesia information management system on timeliness of prophylactic antibiotic administration. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1462–1466. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000263043.56372.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eden A, Pizov R, Toderis L, Kantor G, Perel A. The impact of an electronic reminder on the use of alarms after separation from cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1203–1208. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181984ef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kooij FO, Klok T, Hollmann MW, Kal JE. Decision support increases guideline adherence for prescribing postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:893–898. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31816194fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker DE. Medication alert fatigue: the potential for compromised patient safety. Hospital Pharmacy. 2009;44:460–461. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, Jose J. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010:417–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kesselheim AS, Cresswell K, Phansalkar S, Bates DW, Sheikh A. Clinical decision support systems could be modified to reduce 'alert fatigue' while still minimizing the risk of litigation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2310–2317. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Block FE, Jr, Nuutinen L, Ballast B. Optimization of alarms: a study on alarm limits, alarm sounds, and false alarms, intended to reduce annoyance. J Clin Monit Comput. 1999;15:75–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1009992830942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aranake A, Gradwohl S, Ben-Abdallah A, et al. Increased risk of intraoperative awareness in patients with a history of awareness. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1275–1283. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee U, Ku S, Noh G, Baek S, Choi B, Mashour GA. Disruption of frontal-parietal communication by ketamine, propofol, and sevoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1264–1275. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829103f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casali AG, Gosseries O, Rosanova M, et al. A theoretically based index of consciousness independent of sensory processing and behavior. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:1–10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]