Abstract

Urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were evaluated as possible biomarkers of exposure to diesel exhaust (DE) in two controlled-chamber studies. We report levels of 14 PAHs from 28 subjects in urine that were collected before, immediately after and the morning after exposure. Using linear mixed-effects models, we tested for effects of DE exposure and several covariates (time, age, gender and urinary creatinine) on urinary PAH levels. DE exposures did not significantly alter urinary PAH levels. We conclude that urinary PAHs are not promising biomarkers of short-term exposures to DE in the range of 106–276 μg/m3.

Keywords: Biomarker, diesel exhaust, PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, urine

Introduction

Diesel exhaust (DE) was classified in 2012 as a group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (Benbrahim-Tallaa et al., 2012) based on long-term occupational exposures. DE contributes to ambient particulate matter that has been linked to chronic cardiopulmonary and vascular effects (Sydbom et al., 2001; Wichmann, 2007). Yet, it has been difficult to quantify exposure–response relationships for DE due to the lack of quantitative data regarding exposures, which have primarily been classified by observational descriptors such as job title (Laumbach & Kipen, 2011; Pronk et al., 2009; Steenland et al., 1998). This reflects the complex nature of DE, which is comprised of both gaseous and fine particulate constituents.

Although gaseous DE contains predominantly small molecules such as nitrogen oxides and aldehydes, the particulate phase consists of elemental carbon coated with organic compounds (organic carbon), including particle-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (Sobus et al., 2008a; Sydbom et al., 2001; Wichmann, 2007). The class of PAHs contains hundreds of chemicals with two or more fused-aromatic rings that are formed from incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons. As a class, PAHs have been associated with human lung and bladder cancers, and several of the five-ring PAHs, such as benzo(a)pyrene (BAP), are potent animal carcinogens (IARC, 2010). Volatile or semi-volatile PAH molecules (two or three rings) are found primarily in the gas phase, while the larger compounds (four to six rings) reside primarily in the particulate phase.

Concentrations of gas-phase PAHs are much greater in DE than those of particulate-phase PAHs. For example, Sobus et al. (2008a) reported air concentrations of naphthalene (NAP, two rings) and phenanthrene (PHE, three rings) during controlled human exposure to DE that were about three orders of magnitude greater than the BAP concentration. Because air levels of NAP and/or PHE were highly correlated with those of organic carbon as well as semivolatile and particulate PAHs, the authors speculated that NAP and PHE could be suitable surrogates for exposures to all DE-derived PAHs –and to DE more generally – in studies of health effects (Sobus et al., 2008a). In a separate analysis, Sobus et al. (2008b) showed that the levels of unmetabolized NAP and PHE in urine were also positively correlated in workers exposed to coke-oven emissions, asphalt fumes and DE.

Urinary PAHs are biomarkers of exposure, which offer attractive alternatives to air monitoring for determining exposure–response relationships (Lin, 2005). Many PAHs have been detected in urine from urban populations exposed to air pollutants (Campo et al., 2007, 2009, 2011; Serdar et al., 2003; Sobus et al., 2008b; Waidyanatha et al., 2003) as well as from workers exposed to emissions containing PAHs (Campo et al., 2007, 2009, 2010, 2011; Rossella et al., 2009; Serdar et al., 2003; Sobus et al., 2008b, 2009b; Waidyanatha et al., 2003). Given the abundance of volatile PAHs in DE, we hypothesized that urinary levels of gas-phase PAHs would elevate upon short-term exposure to air concentrations of DE that were well above ambient values. Since urinary PAHs are remarkably simple to measure by headspace gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), they would be particularly useful biomarkers if they were found at higher urine concentrations following DE exposure.

In this study, we analyzed urinary levels of 14 two-ring to five-ring PAHs in volunteer subjects from two chamber studies of DE exposure, namely, an investigation conducted at the US Environmental Protection Agency in Chapel Hill, NC (hereafter “EPA study”, a 2-h exposure to 106 μg/m3 DE measured as PM2.5) (Sobus et al., 2008a) and the second conducted at Lund University, Sweden (hereafter “Lund study”, a 3-h exposure to 276 μg/m3 DE measured as PM1) (Wierzbicka et al., 2014). Our purpose was to determine whether levels of urinary PAH significantly increased after controlled exposure to DE and thus whether urinary PAHs can be used as biomarkers of DE exposure.

Materials and methods

Chamber studies

All subjects were exposed with informed consent under protocols approved by institutional committees for the protection of human subjects at the relevant institutions (EPA study: US EPA and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, study duration 2006–2007 and Lund study: Lund University, study duration 2009–2010). In both studies, urine specimens were collected immediately before exposure (time 1), immediately after exposure (time 2) and the morning following exposure (time 3). Because the estimated half-lives of urinary NAP and PHE are about 8–10 h (Sobus et al., 2009b), these collection times should allow effects of DE on urinary concentrations of volatile PAHs to be estimated at baseline (time 1), following chamber exposure (time 2) and from residual chamber exposure (time 3). Different combinations of PAHs were measured in urine from the two studies as shown in Table 1, which also lists the numbers of measurements that were above the limits of detection (LOD). In the EPA study, each LOD was three times the standard deviation of replicate controls. In the Lund study, each LOD was the upper 95% confidence limit of the linear least-squares intercept of the respective calibration curve.

Table 1.

Summary of PAHs detected in urine and limits of detection (LOD) and numbers of measurements above LOD (n = 60 for EPA study and n = 214 for Lund study).

| Study | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) | LOD (ng/L)a | Number above LOD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA | Naphthalene (NAP) | 3.7 | 60 (100) |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene (TMN) | 0.71 | 60 (100) | |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene (OMN) | 0.49 | 60 (100) | |

| Fluorene (FLU) | 0.27 | 35 (58) | |

| Phenanthrene (PHE) | 1.3 | 60 (100) | |

| Anthracene (ANT) | nd | ndb | |

| Lund | Naphthalene (NAP) | 54 | 190 (89) |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene (TMN) | 12 | 212 (99) | |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene (OMN) | 8.7 | 194 (91) | |

| Acenaphthylene (ACY) | 6.1 | 189 (88) | |

| Phenanthrene (PHE) | 2.6 | 213 (100) | |

| Fluoranthene (FLE) | 1.6 | 213 (100) | |

| Pyrene (PYR) | 1.6 | 213 (100) | |

| Benzo(a)anthracene (BAA) | 5.5 | 42 (20) | |

| Chrysene (CHR) | 2.7 | 212 (99) | |

| Benzo(b)fluoranthene plus | 1.5 | 27 (13) | |

| Benzo(k)fluoranthene (BBK) | |||

| Benzo(a)pyrene (BAP) | 3.3 | 21 (10) |

Limit of detection.

Not determined.

Details of the EPA study (Hubbard et al., 2009; Pleil et al., 2011; Sobus et al., 2008a) and Lund study (Wierzbicka et al., 2014) have been reported. Briefly, all subjects were nonsmokers, and gas-phase PAHs were measured by adsorption on Tenax followed by thermal desorption/GC-MS). The EPA study exposed four males and six females for 2-h during two sessions (diesel or no-diesel) at least three weeks apart with subjects exposed during moderate exercise. During diesel sessions, DE was from an idling commercial vehicle with a six-cylinder, 5.9-L diesel engine, which generated PM2.5 concentrations of 106 ± 9 (SD) μg/m3. Urine voids were combined for each subject over 2-h periods for time 2.

The Lund study exposed nine males and nine females at rest during four sessions at least five days apart. Exposures included diesel and no-diesel sessions, with low or high recorded traffic noise at 46 and 75 dBA, respectively. During diesel sessions, the chamber was supplied with DE from an idling passenger vehicle at PM1 concentrations of 276 ± 27 (SD) μμg/m3, and during no-diesel sessions, filtered air was supplied (PM1 ~ 2 μg/m3). Particulate PAHs were collected on Teflon filters using PM2.5 cyclones and were analyzed by GC-MS (Sällsten et al., 2006). Time 1 and time 3 urine samples were collected at home (before 7:00 in the morning) and time 2 urine samples were collected within 20 min of the end of chamber exposure. Two urine samples of 216 were not available for analysis.

Urinary creatinine measurements

Urinary creatinine (CRE) concentrations were measured with a colorimetric method employing alkaline picrate (Heinegard & Tiderstrom, 1973). Briefly, the three following solutions were prepared: A – 0.05 M sodium borate, 0.05 M sodium phosphate, adjusted to pH 12.7 with sodium hydroxide, B – 4% SDS and C – 1% picric acid. Fifty microliters of CRE standard or 20 × diluted sample were loaded into a 96-well plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Then 100 μL of a mixture of solutions A:B:C at ratio 2:2:1 v/v were added and mixed. After 30 min, the absorbance at 490 nm was read against reference wavelength 580 nm using a PowerWave XS Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Sample CRE concentrations were calculated based on a calibration curve of CRE standards (3.1–100 mg/L).

Urinary PAH measurements

For the EPA study, urinary NAP, 2-methylnaphthalene (TMN), 1-methylnaphthalene (OMN), fluorene (FLU), PHE and anthracene (ANT) were measured as described by Sobus et al. (2008b). Briefly, urine samples were stored on ice for up to 4 h following collection and were then transferred to vials and stored at −80 °C for up to one year prior to analysis. For each sample, a 0.7-mL aliquot of urine was spiked with isotopic PAH internal standards [(2H8)NAP, (2H10)TMN, (2H10)FLU, (2H10)PHE and (2H10)ANT from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC., St. Louis, MO] and analyzed by headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) using a CombiPal auto-sampler (CTC Analytics, Zwingen, Switzerland) and a 10 mm, 100-μm film thickness polydimethylsiloxane fiber with adsorption at 55 °C for 30 min and desorption in the GC inlet at 250 °C for 20 min. The PAHs were measured with a Model 6890N GC coupled to a Model 5973N mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). The following ions were monitored in selected-ion monitoring mode: m/z 128 (NAP), m/z 136 [(2H8)NAP], m/z 142 (TMN and OMN), m/z 152 [(2H10)TMN], m/z 166 (FLU), m/z 178 (PHE and ANT) and m/z 188 [(2H10)PHE and (2H10)ANT]. Calibration curves were prepared using pooled urine from human volunteers spiked with PAHs (giving concentrations of 4, 20, 100, 250, 500, 750 and 1000 ng/L) and the internal standards (giving concentrations of 500 ng/L).

For the Lund study, urine was stored at 4 °C for up to 25 h and then at −20 °C for 3–8 months prior to shipment to the University of California, Berkeley, where it was maintained at −80 °C for up to four months prior to analysis. Urine samples were analyzed for NAP, TMN, OMN, acenaphthylene (ACY), PHE, fluoranthene (FLE), pyrene (PYR), benzo(a)anthracene (BAA), chrysene (CHR), benzo(b)fluoranthene plus benzo(k)-fluoranthene (BBK) and BAP. Two milliliter amber-glass autosampler vials and NaCl were baked in a vacuum oven at 160 °C overnight to remove any residual target compounds. Upon thawing at room temperature, the urine was mixed by inversion and 0.8 mL and was centrifuged for 5 min at 10 000× g to remove sediment. Then 0.7 mL of the supernatant was transferred to an autosampler vial containing 0.3 g NaCl. Two microliters of a mixture containing deuterium-labeled PAH internal standards (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC.) were injected into the urine to give concentrations of 1 μg/L of (2H8)NAP, 200 ng/L of (2H10)PHE, 200 ng/L of (2H10)PYR and 200 ng/L of (2H12)BAP. HS-SPME and GC-MS employed the same instruments as the EPA study. Samples were adsorbed at 85 °C for one hour and desorption was carried out at 275 °C for 20 min. A DB-5 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) fused silica column (60 -m length, 250 -μm diameter and 0.25-μm film thickness) was used with He carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.1 mL/min. The GC was programmed from 45 °C to 320 °C, and the following molecular ions were monitored in the selected-ion monitoring mode: m/z 128 (NAP), m/z 136 [(2H8)NAP], m/z 142 (TMN and OMN), m/z 152 (ACY), m/z 178 (PHE), m/z 188 [(2H10)PHE], m/z 202 (FLE and PYR), m/z 212 [(2H10)PYR], m/z 228 (BAA and CHR), m/z 252 (BBK and BAP) and m/z 264 [(2H12)BAP] (Benzo(b)fluoranthene and benzo(k)fluoranthene could not be chromatographically separated and were thus reported as BBK). The urine for calibration curves was created by pooling urine from 10 healthy non-smoking volunteers and then filtering through EnvirElut PAH cartridges (Agilent Technologies Inc.) to reduce background levels of PAHs. The calibration samples were generated by spiking urine with 2 μL of acetonitrile-diluted PAH calibration mix 47 940-U (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC.) to give final concentrations of 0, 0.2, 2, 20, 200, 2000 or 20 000 ng/L of each PAH, with triplicates at each concentration. The calibration curves (R2>0.96) were generated by ordinary least squares linear regression of calibration data (averages of triplicates) from a range of concentrations that was close to that of sample concentrations. The urine PAH levels from the study were estimated by fitting the response ratios of PAHs to their corresponding (same ring number) internal standards on the calibration curves.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics and Student’s t-tests were generated using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and Stata Statistical Software release 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The level of statistical significance was α = 0.05 unless otherwise stated. After adjusting urinary PAH levels for CRE, median values were estimated using all observations (including imputed values) within each study. Trends and correlation coefficients were generated using ordinary least squares linear regression of logged (base 10) levels. If a PAH was detected in a sample, the observed concentration was used even if it was below the LOD. When a PAH was not detected, its urine concentration was imputed using the operative (Table 1). The following non-detected observations were imputed: EPA study –FLU (n = 16); Lund study – NAP (n = 10), TMN (n = 2), ACY (n = 23), BAA (n = 4), CHR (n = 2), BBK (n = 31) and BAP (n = 105). Non-detected observations for ANT (n = 29) were not imputed due to the unavailability of a LOD.

Post-exposure background ratios were calculated from CRE-adjusted PAH levels by dividing the urinary PAH levels measured immediately after exposure (time 2) by those collected prior to exposure (time 1). Since subjects from the Lund study had repeated diesel and no-diesel measurements, subject-specific means of ratios were used. Likewise, morning-after-exposure background ratios were calculated by dividing CRE-adjusted PAH levels measured the following morning (time 3) by those collected at time 1. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks tests were performed to compare the background ratios between diesel and no-diesel sessions after Bonferroni correction of significance levels (EPA study: α = 0.05/5 = 0.01; Lund study: α = 0.05/11 = 0.0045). In the EPA study, ANT was excluded since many of its background ratios were unavailable.

Linear mixed-effects models for each urinary PAH (log-transformed, ng/L) were generated using the xtmixed command of Stata, using exposure status (diesel or no-diesel), time of urine collection (time 1, time 2 or time 3), exposure status × time interactions, gender and the urinary CRE concentration (g/L, log-transformed) as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. Only detected observations were used. Models that included imputed values produced similar results; models that excluded values below LODs had lower rates of convergence, but those that converged produced essentially the same results. Dummy variables were assigned using no-diesel, time 1 and female as reference groups. For the Lund study, we found no effect of added traffic noise on PAH levels (data not shown) and, therefore, excluded noise as a categorical variable, while retaining the diesel and no-diesel data. The following four models were fit using maximum likelihood estimation for each PAH:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where PAHijk is the concentration and εijk is the residual error of a given urinary PAH for the ith subject, the jth exposure and the kth urine sample; β0 (intercept) through β5 are the fixed effects and μ0i is the subject-specific random effect for the ith subject. For the EPA study, i = 1,. . . , 10 and for the Lund study, i = 1,. . . , 18. Note that models (1) and (2) were fit using only time 1 (reference) and time 2 observations and models (3) and (4) were fit using only time 1 and time 3 observations. Because models (1) and (3) included diesel × time interaction terms, statistical evidence for better fits of model (1) relative to model (2) or of model (3) relative to model (4) would indicate that DE significantly affected urinary levels of a given PAH either immediately following exposure or on the morning after exposure, respectively. Goodness-of-fit between models (1) and (2) and between models (3) and (4) were compared with likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs) using the lrtest command of Stata with Bonferroni-adjusted significance (EPA study: α = 0.05/6 = 0.0083; Lund study post-exposure: α = 0.05/9 = 0.0056 and morning-after-exposure α = 0.05/8 = 0.0063).

Results

Urinary PAH levels

In the Lund study, a higher HS-SPME extraction temperature was used than in the earlier EPA study to permit detection of several four-ring and five-ring PAHs. However, the higher temperature used in the Lund study also raised the LOD and decreased sensitivity for the two-ring and three-ring PAHs and, in the case of the more volatile PAHs (especially NAP), may have contributed to imprecise measurements. Table 1 lists the numbers of observations exceeding the respective LODs in both studies. Detection rates decreased from nearly 100% for some two-ring and three-ring compounds to about 10% for five-ring PAHs. As shown by summary statistics in Table 2, the median levels of two-ring PAHs (NAP, TMN or OMN) were greater than those of the three-ring PAHs (ACY, FLU, PHE or ANT) in both studies, while median concentrations of three-ring compounds exceeded those of four-ring and five-ring PAHs (FLE, PYR, BAA, CHR, BBK or BAP) in the Lund study. Urinary PAH concentrations, stratified by exposure status and time, are given in Supplementary Materials, Table S1 for unadjusted PAH levels and Table S2 for CRE-adjusted PAH levels.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for urinary PAHs, ng/L (n = 60 for EPA study and n = 214 for Lund study, including imputed values for non-detected observations).

| Study | PAH | No. rings | Minimum | Median | Interquartile range | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA | NAP | 2 | 4.9 | 12 | 9.6–14 | 50 |

| TMN | 2 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 2.7–5.8 | 16 | |

| OMN | 2 | 0.52 | 2.7 | 1.4–5.1 | 22 | |

| FLU | 3 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.19–0.39 | 1.7 | |

| PHE | 3 | 0.55 | 1.4 | 0.91–2.5 | 13 | |

| ANT | 3 | n/a | 0.24 | n/a–0.62 | 2.1 | |

| Lund | NAP | 2 | 0.89 | 310 | 170–580 | 3200 |

| TMN | 2 | 8.2 | 99 | 57–180 | 750 | |

| OMN | 2 | 1.4 | 24 | 14–37 | 110 | |

| ACY | 3 | 4.3 | 20 | 12–40 | 84 | |

| PHE | 3 | 1.8 | 18 | 7.9–33 | 400 | |

| FLE | 4 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 3.0–4.7 | 17 | |

| PYR | 4 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 3.9–4.9 | 7.4 | |

| BAA | 4 | 0.016 | 2.6 | 1.2–4.9 | 30 | |

| CHR | 4 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 3.0–3.3 | 5.4 | |

| BBK | 5 | 0.41 | 1.0 | 0.82–1.2 | 9.5 | |

| BAP | 5 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.3–2.3 | 21 |

ACY, acenaphthylene; ANT, anthracene; BAA, benzo(a)anthracene; BAP, benzo(a)pyrene; BBK, benzo(b)fluoranthene plus benzo(k)fluor-anthene; CHR, chrysene; FLE, fluoranthene; FLU, fluorene; NAP, naphthalene; OMN, 1-methylnaphthalene; PHE, phenanthrene; PYR, pyrene; and TMN, 2-methylnaphthalene.

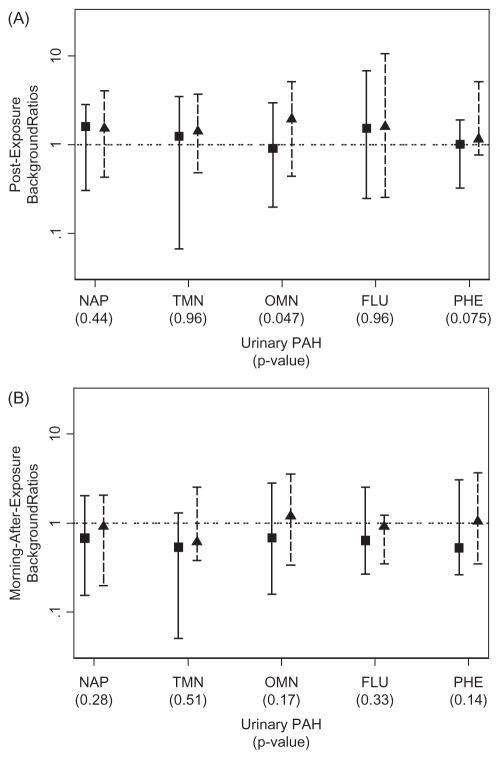

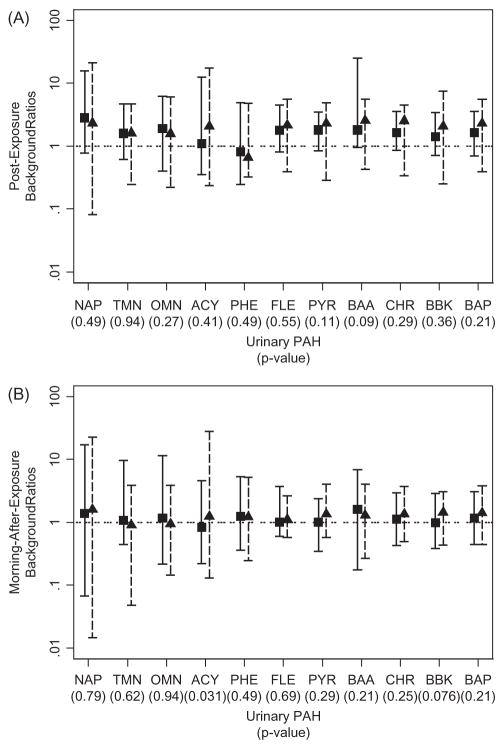

Background ratios

Univariate statistics employed background ratios to determine whether DE exposure affected PAH levels either immediately following (time 2) or on the morning after exposure (time 3). As shown in Figures 1 and 2, ranges of background ratios for a given PAH spanned about 100-fold (from 0.1 to 10), indicating that urinary PAH levels varied greatly across individual subjects in each study. In both studies, background ratios were marginally greater immediately after exposure, but this was the case for both diesel and no-diesel sessions. In fact, no difference in background ratios was observed between diesel and no-diesel sessions for any PAH in either study, using Bonferroni-adjusted p values. When we repeated the analyses using unadjusted PAH levels to calculate background ratios, the results and plots were essentially the same (not shown).

Figure 1.

Background ratios of urinary PAH levels for the EPA study using creatinine-adjusted data (imputed observations are included; squares and triangles represent medians of background ratios from no-diesel and diesel sessions, respectively; solid line and dashed bars represent the ranges of background ratios from no-diesel and diesel sessions, respectively). p Values refer to significance of comparisons of background ratios between diesel and no-diesel sessions. FLU, fluorene; NAP, naphthalene; OMN, 1-methylnaphthalene; PHE, phen-anthrene; and TMN, 2-methylnaphthalene.

Abbreviations: FLU, fluorene; NAP, naphthalene; OMN, 1-methylnaphthalene; PHE, phenanthrene; TMN, 2-methylnaphthalene.

Figure 2.

Background ratios of urinary PAH levels for the Lund study, using creatinine-adjusted data (imputed observations are included; squares and triangles represent medians of background ratios from no-diesel and diesel sessions, respectively; solid line and dashed bars represent the ranges of background ratios from no-diesel and diesel sessions, respectively). p Values refer to significance of comparisons of background ratios between no-diesel and diesel sessions. ACY, acenaphthylene; BAA, benzo(a)anthracene; BAP, benzo(a)pyrene; BBK, benzo(b)fluoranthene plus benzo(k)fluoranthene; CHR, chrysene; FLE, fluoranthene; NAP, naphthalene; OMN, 1-methylnaphthalene; PHE, phenanthrene; PYR, pyrene; and TMN, 2-methylnaphthalene.

Mixed models

Results from the mixed-effects models are summarized in Table 3 along with p values from the LRTs (comparisons were not available for six pairs of models because of non-convergence). By comparing the fits between models (1) and (2) and models (3) and (4), we tested whether inclusion of the diesel × time interaction term was justified, and by extension, whether exposure to DE affected urinary PAH levels. Of the 28 LRTs, only OMN in the post-exposure samples from the EPA study showed a significant interaction term (p value = 0.008). (Results for OMN from the Lund study could not be tested because the models did not converge.) This indicates that, with the possible exception of OMN, DE was not significantly associated with increased levels of any measured PAH in subjects’ urine. Of the 29 models without interaction terms (models 2 and 4), significant effects of diesel, time 2, time 3 and gender were only sporadically observed and the signs of diesel and time 2 effects were inconsistent across PAHs. In fact, CRE concentrations and intercepts were the only fixed effects consistently associated with urinary PAH levels. Thus, we conclude that DE sessions did not alter urinary PAH levels after adjustment for other covariates, consistent with the univariate results summarized in Figures 1 and 2. This probably reflects masking of DE exposure by other exposure sources, including the diet and the background environment. Since diet is the main source of PAH exposure for nonsmokers (IARC, 2010), dietary sources could have overwhelmed the contribution of DE during two or three hours of experimental exposure.

Table 3.

Results from linear mixed-effects models for urinary PAHs.

| Post-exposure (Model 2) parameters

|

Morning-after-exposure (Model 4) parameters

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | PAH | Diesel | Time 2 | Gender | ln(CRE) | Int. | LRT | Diesel | Time 3 | Gender | ln(CRE) | Int. | LRT |

| EPA | NAP | +b | +b | 0.206 | +b | +b | 0.118 | ||||||

| TMN | +a | +b | 0.101 | +a | +b | 0.021 | |||||||

| OMN | +b | +b | 0.008c | – | +b | +b | 0.056 | ||||||

| FLU | −b | 0.599 | +b | −b | 0.149 | ||||||||

| PHE | −a | +a | +b | 0.049 | – | +b | +b | 0.055 | |||||

| ANT | + | n/ad | + | −a | 0.628 | ||||||||

| Lund | NAP | +b | 0.036 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/ad | ||||

| TMN | +b | +b | 0.345 | +b | 0.032 | ||||||||

| OMN | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/ad | – | +b | 0.392 | ||||

| ACY | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/ad | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/ad | |

| PHE | −b | +b | +b | 0.432 | −a | +b | +b | 0.686 | |||||

| FLE | +b | +b | +b | 0.412 | +b | +b | 0.117 | ||||||

| PYR | – | + | +b | 0.198 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/ad | |||

| BAA | +a | +b | 0.690 | +b | 0.144 | ||||||||

| CHR | + | + | +a | +b | 0.986 | +a | +b | 0.312 | |||||

| BBK | – | +a | + | 0.831 | + | 0.775 | |||||||

| BAP | – | +a | +b | 0.152 | −a | −a | +b | +b | 0.475 | ||||

0.0005 ≤ p<0.01.

p<0.0005.

Statistically significant LRT using the Bonferroni-corrected α.

The corresponding model including diesel × time interaction did not converge.

Structure of tests: “diesel” – diesel exposure compared to no-diesel exposure (reference); “time 2” – post-exposure compared to pre-exposure (reference); “time 3” – morning after exposure compared to pre-exposure (reference); “gender” – male compared to female (reference); “CRE”, urinary creatinine (continuous variable); “Int.”, intercept; LRT, likelihood-ratio test comparing models (1) to (3) or models (2) to (4).

ACY, acenaphthylene; ANT, anthracene; BAA, benzo(a)anthracene; BAP, benzo(a)pyrene; BBK, benzo(b)fluoranthene plus benzo(k)fluoranthene; CHR, chrysene; FLE, fluoranthene; FLU, fluorene; NAP, naphthalene; OMN, 1-methylnaphthalene; PHE, phenanthrene; PYR, pyrene; and TMN, 2-methylnaphthalene.

Plus indicates a significant positive association and minus indicates a significant negative association. Models that did not converge are indicated by n/a. The p values are given for likelihood-ratio tests (LRT) comparing models (1) and (2) or models (3) and (4). A significant LRT would indicate a significant diesel × time interaction term.

Linear mixed-effects models have been used previously to investigate urinary PAHs as potential biomarkers in a study of workers exposed to asphalt (Sobus et al., 2009a). In that study, workers were exposed to PAHs both by inhalation and dermal absorption and both routes of exposure produced significant effects on urinary levels of NAP and PHE (the only PAHs reported). As in this investigation, Sobus et al. (2009a) observed significant effects of urinary CRE on urinary NAP and PHE levels but also detected significant effects of work activities and the timing of urine collection.

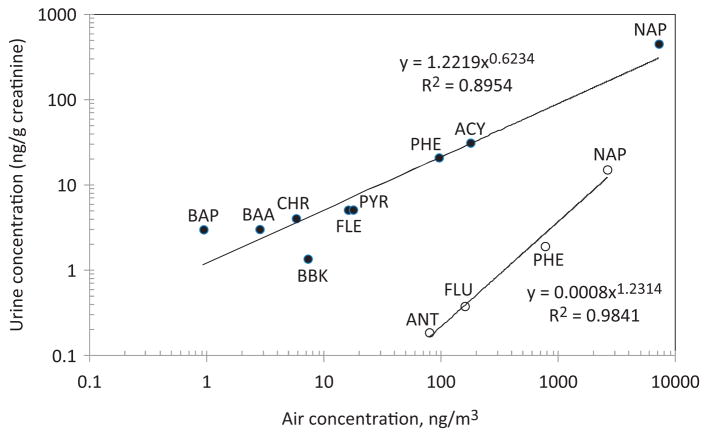

Urinary versus airborne PAHs

An unexpected result from our studies was the strong positive correlations between median levels of CRE-adjusted urinary PAHs and mean levels of airborne PAHs (shown in Supplementary Materials, Table S3) to which subjects were exposed in the chambers. As shown by the log-scale plots in Figure 3 between 90% and 98% of the variation in urinary PAH levels was explained by the corresponding PAH air concentrations. Since the mixed-model results (Table 3) showed that DE sessions did not increase urinary PAH levels, the relationships shown in Figure 3 suggest that profiles of urinary PAHs also reflect background PAH exposures received by the subjects in the respective EPA and Lund studies. In fact, each set of the CRE-adjusted urinary PAHs, stratified by exposure status and time, had correlation coefficients with airborne PAHs between 86% and 99% (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Log-scale plots of median urinary-PAH levels versus mean airborne-PAH levels during diesel-exhaust exposure (closed symbols represent the Lund study and open symbols represent the EPA study). (Air levels of TMN and OMN were not measured). ACY, acenaphthylene; ANT, anthracene; BAA, benzo(a)anthracene; BAP, benzo(a)pyrene; BBK, benzo(b)fluoranthene plus benzo(k)fluoranthene; CHR, chrysene; FLE, fluoranthene; FLU, fluorine; NAP, naphthalene; PHE, phenanthrene; and PYR, pyrene.

Discussion

Table 4 lists baseline urinary concentrations of NAP and PHE from several urban populations and occupationally exposed populations at the beginning of a work week. The fold ranges of urinary NAP and PHE concentrations across studies were 72 and 44, respectively. This highlights the importance of having geographically matched controls in biomarker studies for ubiquitous contaminants such as PAHs. The EPA study had the lowest values of urinary NAP and PHE shown in Table 4, while the Lund study had values at the higher end. (Note that the Lund study NAP result may have been anomalously high due to reduced sensitivity of the analytical method.)

Table 4.

Comparison of urinary naphthalene (NAP) and phenanthrene (PHE) concentrations (ng/L) from the current studies with published data from urban populations or pre-shift urine from workers.

| NAP median (minimum–maximum) | PHE median (minimum–maximum) | No. of subjects | No. of smokers | Type of subjects | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 859 (107–3170) | 62 (8–690) | 22 | 3 | Controls | China | Waidyanatha et al. (2003) |

| 310 (0.89–3200) | 18 (1.8–400) | 18 | 0 | DE exposed and controls | Sweden | Current Lund study |

| 155 (99.4–191) | 25.7 (20.7–58.6) | 5 | 5 | Controls | Italy (assumed) | Campo et al. (2009) |

| 69 (32–225) | 22 (10–109) | 100 | 44 | Baseline, asphalt workers | Italy | Campo et al. (2007) |

| 61 (25–175) | 21 (9–97) | 47 | 30 | Baseline, construction workers | Italy | Campo et al. (2007) |

| 36.2 (21.0–63.1) | 15.5 (3.89–62.0) | 6 | 1 | Baseline, millers | US | Sobus et al. (2009b) |

| 24.5 (7.46–190) | 7.64 (0.45–44.5) | 20 | 5 | Baseline, pavers | US | Sobus et al. (2009b) |

| 27 (GM) | n/a | 26 | 26 | Control military personnel, pre-shift | US | Serdar et al. (2003) |

| 2.46 (GSD) | ||||||

| 14 (GM) | n/a | 48 | 0 | Control military personnel, pre-shift | US | Serdar et al. (2003) |

| 4.79 (GSD) | ||||||

| 22.0 (4.71–46.1) | 3.53 (0.82–11.2) | 27 | 11 | Pre-shift, dock workers | US | Sobus et al. (2008b) |

| 16.3 (8.50–22.0) | 3.61 (1.92–11.6) | 4 | 1 | Pre-shift, office workers | US | Sobus et al. (2008b) |

| 14.0 (6.89–22.2) | 4.54 (1.54–11.8) | 8 | 1 | Pre-shift, shop workers | US | Sobus et al. (2008b) |

| 12 (4.9–50) | 1.4 (0.55–13) | 10 | 0 | DE exposed and controls | US | Current EPA study |

GM, geometric mean and GSD, geometric standard deviation.

Although urinary levels of unmetabolized PAHs were not significantly affected by DE sessions, PAH metabolites that are present at much greater abundance than their parent compounds in urine may be more robust biomarkers of DE. For example, 1-hydroxypyrene (a metabolite of PYR), has been a significant indicator of occupational DE exposure studies, many of which also included smoking status and/or genotypic expression of metabolizing enzymes (Adonis, 2003; DeMarini, 2013). Although our controlled experiments with non-smokers avoided the confounding effect of smoking, we found no association between DE exposure and levels of urinary PYR, the precursor for 1-hydroxypyrene. Another PAH biomarker is 1-aminopyrene (Huyck et al., 2010; Laumbach et al., 2009), a metabolite of 1-nitropyrene that is at least 10-fold more abundant in DE than in ambient air (Bamford et al., 2003). Following controlled exposure of 55 subjects for 1 h to DE containing 1-nitropyrene at 2.68 ng/m3, the median 24-h time-weighted concentration of urinary 1-aminopyrene was 139 ng/g CRE compared with 21.7 ng/g CRE following exposure to clean air (Laumbach et al., 2009).

Conclusions

We measured several unmetabolized two-ring to five-ring PAHs in 274 urine samples from 28 subjects after controlled exposures to DE in two chamber studies. There was no increase in urinary PAH levels associated with DE after adjusting for other covariates. This unexpected result probably reflects masking of PAH from DE by contributions from the diet and background environment. Since the diet is the main source of PAH exposure for most nonsmokers (IARC, 2010), dietary sources could have overwhelmed the contribution of DE during two or three hours of experimental exposure even though the DE levels (106–276 μg/m3) were high compared to ambient sources of DE, and the EPA study increased the alveolar ventilation rate – and DE absorption –by exposing subjects under moderate exercise. In any case, our results from two controlled chamber studies indicate that urinary PAHs are not promising biomarkers of DE exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all test subjects taking part in the studies as well as colleagues involved in conducting the chamber studies. The authors appreciate the suggestions of Silvia Fustinoni and Suramya Waidyanatha regarding assays of urinary PAHs in the EPA study.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

None of the authors has any actual or potential competing financial interests.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-0946797 to S. S. L. and by grants P42ES05948 and P42ES04705 from the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (to S. M. R.). The Lund study is a part of a larger DINO project “Health effects of combined exposure to diesel and noise” financed by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS.

This report has been reviewed by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, United States Environmental Protection Agency and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Agency nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

References

- Adonis M. Susceptibility and exposure biomarkers in people exposed to PAHs from diesel exhaust. Toxicol Lett. 2003;144:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford HA, Bezabeh DZ, Schantz S, et al. Determination and comparison of nitrated-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons measured in air and diesel particulate reference materials. Chemosphere. 2003;50:575–87. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Baan RA, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of diesel-engine and gasoline-engine exhausts and some nitroarenes. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:663–4. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo L, Fustinoni S, Buratti M, et al. Unmetabolized polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urine as biomarkers of low exposure in asphalt workers. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2007;4:100–10. [Google Scholar]

- Campo L, Mercadante R, Rossella F, Fustinoni S. Quantification of 13 priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human urine by headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography–isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;631:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo L, Rossella F, Pavanello S, et al. Urinary profiles to assess polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure in coke-oven workers. Toxicol Lett. 2010;192:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo L, Fustinoni S, Bertazzi P. Quantification of carcinogenic 4- to 6-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human urine by solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography–isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;401:625–34. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarini DM. Genotoxicity biomarkers associated with exposure to traffic and near-road atmospheres: a review. Mutagenesis. 2013;28:485–505. doi: 10.1093/mutage/get042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinegard D, Tiderstrom G. Determination of serum creatinine by a direct colorimetric method. Clin Chim Acta. 1973;43:305–10. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(73)90466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard HF, Sobus JR, Pleil JD, et al. Application of novel method to measure endogenous VOCs in exhaled breath condensate before and after exposure to diesel exhaust. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877:3652–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyck S, Ohman-Strickland P, Zhang L, et al. Determining times to maximum urine excretion of 1-aminopyrene after diesel exhaust exposure. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2010;20:650–5. doi: 10.1038/jes.2010.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Some non-heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;92:1–853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumbach R, Tong J, Zhang L, et al. Quantification of 1-aminopyrene in human urine after a controlled exposure to diesel exhaust. J Environ Monit. 2009;11:153–9. doi: 10.1039/b810039j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumbach RJ, Kipen HM. Does diesel exhaust cause lung cancer (yet)? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:843–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1870ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YS. Air samples versus biomarkers for epidemiology. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:750–60. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.013102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleil JD, Stiegel MA, Madden MC, Sobus JR. Heat map visualization of complex environmental and biomarker measurements. Chemosphere. 2011;84:716–23. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk A, Coble J, Stewart PA. Occupational exposure to diesel engine exhaust: a literature review. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19:443–57. doi: 10.1038/jes.2009.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossella F, Campo L, Pavanello S, et al. Urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and monohydroxy metabolites as biomarkers of exposure in coke oven workers. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:509–16. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.042796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sällsten G, Gustafson P, Johansson L, et al. Experimental wood smoke exposure in humans. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:855–64. doi: 10.1080/08958370600822391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serdar B, Egeghy PP, Waidyanatha S, et al. Urinary biomarkers of exposure to jet fuel (JP-8) Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1760–4. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobus JR, Pleil JD, Madden MC, et al. Identification of surrogate measures of diesel exhaust exposure in a controlled chamber study. Environ Sci Technol. 2008a;42:8822–8. doi: 10.1021/es800813v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobus JR, Waidyanatha S, McClean MD, et al. Urinary naphthalene and phenanthrene as biomarkers of occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Occup Environ Med. 2008b;66:99–104. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobus JR, McClean MD, Herrick RF, et al. Comparing urinary biomarkers of airborne and dermal exposure to polycyclic aromatic compounds in asphalt-exposed workers. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009a;53:561–71. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mep042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobus JR, McClean MD, Herrick RF, et al. Investigation of PAH biomarkers in the urine of workers exposed to hot asphalt. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009b;53:551–60. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mep041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Deddens J, Stayner L. Diesel exhaust and lung cancer in the trucking industry: exposure-response analyses and risk assessment. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34:220–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199809)34:3<220::aid-ajim3>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydbom A, Blomberg A, Parnia S, et al. Health effects of diesel exhaust emissions. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:733–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17407330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waidyanatha S, Zheng Y, Rappaport SM. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urine of coke oven workers by headspace solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;145:165–74. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann HE. Diesel exhaust particles. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19:241–4. doi: 10.1080/08958370701498075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka A, Nilsson PT, Rissler J, et al. Detailed diesel exhaust characteristics including particle surface area and lung deposited dose for better understanding of health effects in human chamber exposure studies. Atmos Environ. 2014;86:212–19. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.