Abstract

Objective An acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a rare cause of vaginal bleeding and, although hysterectomy is the definitive therapy, transcatheter embolization (TCE) provides an alternative treatment option. This systematic review presents the indications, technique, and outcomes for transcatheter treatment of the acquired uterine AVMs.

Study Design Literature databases were searched from 2003 to 2013 for eligible clinical studies, including the patient characteristics, procedural indication, results, complications, as well as descriptions on laterality and embolic agents utilized.

Results A total of 40 studies were included comprising of 54 patients (average age of 33.4 years). TCE had a primary success rate with symptomatic control of 61% (31 patients) and secondary success rate of 91% after repeated embolization. When combined with medical therapy, symptom resolution was noted in 48 (85%) patients without more invasive surgical procedures.

Conclusion Low-level evidence supports the role of TCE, including in the event of persistent bleeding following initial embolization, for the treatment of acquired uterine AVMs. The variety of embolic agents and laterality of approach delineate the importance of refining procedural protocols in the treatment of the acquired uterine AVM.

Condensation A review on the management of patients with acquired uterine AVMs.

Keywords: uterus, arteriovenous malformation, embolization, endovascular, postpartum hemorrhage

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) can be found anywhere in the vascular system, including the uterus.1 An acquired uterine AVM is a rare cause of life-threatening bleeding that may be the result of trauma, surgical intervention, or in the setting of a preexisting pathologic uterine process. Historically, treatment for uterine AVMs required hysterectomy2; however, transcatheter vascular embolization (TCE) has provided an alternative treatment option for patients wishing to preserve fertility. Nevertheless, the method and approach of transcatheter treatment and the embolic agent utilized varies in the literature. In this systematic review, acquired uterine AVMs will be discussed in regards to (1) pathophysiology, (2) clinical presentation, (3) diagnostic strategies, (4) treatment approaches, and (5) postprocedural patient management.

Material and Methods

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed in Medline, Cochrane, and Embase from 2003 to 2014. The applied search heading included combinations of the following terms: “uterine arteriovenous malformation,” “uterine AVM,” “uterus and malformation,” “uterine fistula,” “uterine shunt,” “hysterectomy,” “resection,” “surgical,” and “embolization” limited to clinical studies published in the English language. Titles and abstracts were screened to identify relevant articles. Referred and related articles were checked. Articles were selected following the selection criteria below and evaluated by two of the authors (D. J. Y., J. D. D.) using a scoring list. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Selection Criteria and Data Extraction

All clinical studies on acquired uterine AVM were included for further evaluation. Acquired AVM was defined as a uterine AVM pertaining to or diagnosed following trauma, surgical intervention, or in the setting of a preexisting pathologic uterine process. Included articles described the uterine AVM as acquired and included a description of the underlying pathology. Articles were excluded if they were review articles or animal studies, or did not describe the specifics of the technical approach as below. All included studies were evaluated for study quality characteristics by two reviewers and included: (1) patient characteristics (number of patients, age, time of diagnosis, method of diagnosis, inciting cause of the acquired uterine AVM); (2) indication for embolization; (3) embolization technique (unilateral or bilateral) and embolic material utilized; (4) technical outcome; (5) follow-up (clinical success rate, postprocedural complications and morbidity, postprocedural imaging); (6) requirement for additional embolization procedure, medical management, or surgery. Articles were valid and used for data extraction if the above-mentioned points were clearly described.

Results

The broad initial search using the search heading “uterine arteriovenous malformation” resulted in 304 publications. Primary survey of the abstracts and articles excluded 224 articles dealing with subjects other than transcatheter embolization, animal studies, reviews or articles in a non-English language. After critical evaluation of the remaining full text articles for acquired uterine AVMs, 40 articles remained for final inclusion meeting the minimum requirements above and comprised of 39 case reports2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 and one retrospective study.41 The cumulative evaluated population comprised of 54 women with a mean age of 33.5 years. The underlying pathology is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Associated clinical history for reported cases of acquired uterine AVM.

| Associated clinical history | Number (%) |

| D&C | 34 (62) |

| C-section | 14 (26) |

| Uterine instrumentation procedures (hysteroscopy, placental delivery, and IUD placement) | 2 (4) |

| Myomectomy | 2 (4) |

| GTT | 2 (4) |

| Total | 54 |

Abbreviations: AVM, arteriovenous malformation; D&C, dilation and curettage; GTT, Gestational trophoblastic tumor; IUD, intrauterine device.

Pathophysiology of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformations

Based on the vascular anomaly classification proposed by Mulliken and Glowaki, AVMs can be defined as a vascular structural anomaly involving abnormal communication between arteries and veins that bypass the capillary system.42 AVMs can be further categorized as high-flow vascular malformations as typified by a high-pressure gradient across the arterial and venous system that enables a high vascular flow through the nidus, the intervening network of vessels communicating the arteries to the veins. Alternatively, a direct communication may exist in the absence of a nidus representing a fistulous connection of the arteries and venous structures. Though AVMs involving the uterus are rare, if present, they can be a serious cause of recurrent and intermittent menorrhagia.

Uterine AVMs are divided into congenital and acquired AVMs. Congenital AVMs result from a defect in the differentiation of the primitive capillary plexus during fetal angiogenesis.43 44 45 46 In contradistinction, acquired AVMs are vascular abnormalities usually present after trauma, surgical intervention, or in the setting of a preexisting pathologic uterine process. An acquired uterine AVM is characterized by a single arteriovenous communication between the branches of the uterine artery and the myometrial venous plexus. Indeed, terms, including “arteriovenous fistula,” “traumatic uterine arteriovenous malformation,” and “arteriovenous shunt” are interchangeably used in the literature, despite their differences, to describe such acquired pathology which may be difficult to differentiate. To follow those descriptions in the literature and for the purposes of this review, these terms are also collectively referred to as acquired uterine AVM although the exact underlying pathophysiology is not well understood.8 Although the term malformation may suggest a congenital etiology, acquired uterine AVMs develop following an inciting event, differentiating them from their congenital counterpart. For instance, packing and clamping for hemostatic control during surgery can cause shunting of blood from the capillary plexus to the less resistant venous system possibly resulting in fistula formation after uterine procedures.10 Case reports have described acquired AVM formation following uterine dilation and curettage (D&C), cesarean section, and myomectomy.6 8 Pathologic processes such as infection, trophoblastic disease, and malignancies involving the uterus have also been described as associated with acquired AVM.47

The association of pregnancy and worsening symptoms of acquired uterine AVM formation suggests a hormonal mechanism. Pregnancy and associated hormonal changes, such as elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG),48 may play a role in the proliferation of otherwise latent AVMs through an unclear mechanism.7 47 Similarly, women undergoing fertility treatments may be at higher risk secondary to elevated estrogen level, causing endothelial proliferation and differentiation of the endometrium.48 However, menorrhagia after pregnancy may also be a representation of retained product of conceptions or nonobliteration and subinvolution of the blood vessels of the placental bed rather than secondary to AVM formation.44 49 These former entities share similar radiologic findings with acquired AVMs, which can make differentiation of these separate pathologic processes difficult.44 Ultimately, increased efforts to identify those mechanisms underlying the formation of acquired uterine AVMs may allow for the identification of those patients at risk for their development and prompt early and close follow-up to avoid the associated complications.

Clinical Presentation

Acquired uterine AVMs are typically identified in symptomatic, multiparous women of childbearing age. A systematic review of the demographics of iatrogenic, acquired AVMs by Peitsidis et al revealed the mean age of women diagnosed with a uterine AVM was 30 years.50 Acquired uterine AVM rarely affects nulliparous women without a history of uterine trauma secondary to gynecological procedures.47 The most common presenting symptoms of an acquired uterine AVM are menorrhagia and metrorrhagia. Bleeding is often intermittent and torrential.4 This is secondary to the high vascular flow across the involved lesion due to the differential pressure gradient across the arterial and venous systems. These patients may also present with anemia and hypotension, secondary to acute blood loss. Peitsidis et al recently identified that approximately 50% of patients with acquired uterine AVM required blood transfusion secondary to the associated anemia.50 Vague pelvic discomfort, urinary symptoms, including polyuria and incontinence, and dyspareunia are common complaints.4 Congestive heart failure secondary to the shunting of blood to the venous system is possible but is rare.51 A history of recurrent spontaneous abortion may also place a patient at higher risk for acquired uterine AVM formation, possibly due to the increased vascularization and resultant physical alteration of the embryo's implantation site.33 Despite these common presenting symptoms, patients may alternatively remain asymptomatic despite the presence of a uterine AVM. Asymptomatic patients may later develop symptoms following uterine trauma or secondary to hormonal changes related to pregnancy or the menstrual cycle.52

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a woman of childbearing age presenting with menorrhagia and metrorrhagia is broad.53 Although rare, acquired uterine AVM should be considered in patients with appropriate history and presenting symptoms. Notably, the typical treatment options for uterine bleeding, such as D&C, can cause uterine trauma and paradoxically worsen the bleeding in the presence of an acquired AVM. D&C is therefore contraindicated in acquired uterine AVM or those patients with suspected acquired AVM.4 If there is increased bleeding during a D&C performed for abnormal uterine bleeding, then a uterine AVM should be suspected and the appropriate precautions taken for the possibility of ongoing severe hemorrhage.

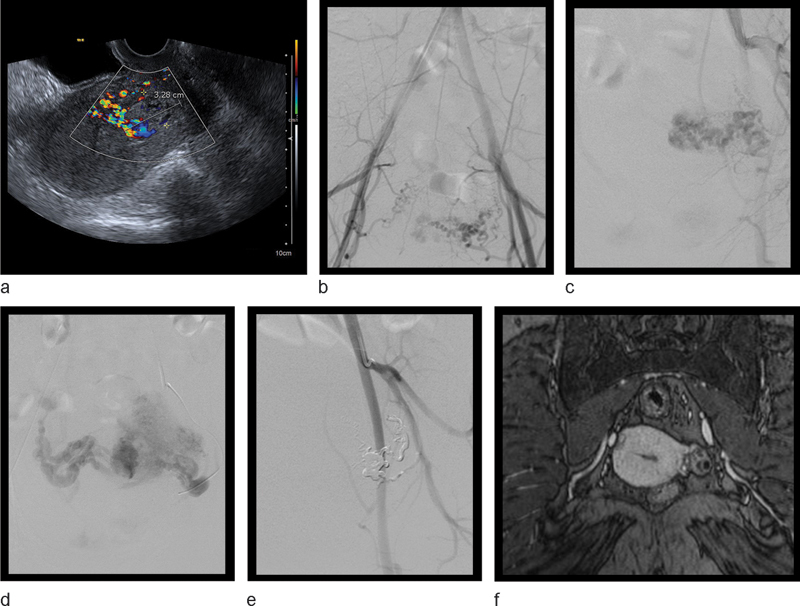

Historically, acquired uterine AVM was diagnosed by pathology after hysterectomy.44 Recently, less invasive imaging studies have been utilized for diagnostic purposes to guide therapeutic options. Transvaginal ultrasound is the initial imaging study of choice for abnormal uterine bleeding. As a definitive diagnosis based on grayscale ultrasound imaging is difficult alone, Doppler imaging is imperative to the diagnosis. The presence of a tubular, hypoechogenic structure in the myometrium by grayscale ultrasound imaging, although common, is not specific for uterine AVM. The identification of uterine high velocity blood flow with low impedance by Doppler ultrasound is highly suggestive for a uterine AVM44 54 (Fig. 1a). As mentioned earlier, subinvolution of the placental bed and adenomyosis in the setting of menorrhagia also can have similar ultrasound findings such as hypervascularity and turbulent flow. There are no firm criteria to differentiate between an AVM and the subinvolution of the placenta by ultrasound.44 This raises a concern for the overdiagnosis of uterine AVM. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is thus recommended for the evaluation beyond ultrasound for uterine AVM when indicated, particularly in cases when the acoustic windows are limited by body habitus or technique. MRI findings include serpiginous signal voids in the uterus and enhancement of the signal voids on rapid data acquisition during infusion of contrast.54 55 56 MRI provides better tissue contrast and helps delineate the surrounding pelvic organ involvement. Acquired AVM primarily involves the myometrium while retained products of conception primarily involve the endometrium.56 The diagnosis can be confirmed when these imaging findings are coupled with maternal serum hCG, which has a slower decline in retained products of conception. Computed tomography (CT) can assess the degree of involvement of the surrounding visceral structures57; however, utilizes ionizing radiation, which should be avoided in women of childbearing age and does not contribute additional information beyond that garnered by MRI. Characteristic CT findings include the presence of a soft-tissue density mass with enhancement pattern resembling adjacent vessels.58 Angiography should be offered in consideration for a possible therapeutic option following diagnostic confirmation. The typical findings of a uterine AVM by angiography include high arterial flow with early venous filling (Fig. 1c, d). A single direct fistulous communication to the venous structures may be identified. This finding is more common in acquired AVM (Fig. 1d) than in congenital AVM, where contrast filling of a vascular plexus or nidus is more commonly seen.44 In this representative case (Fig. 1e), a novel treatment approach to uterine AVMs was utilized in which the malformation was embolized using a nonadhesive liquid embolic agent, Onyx (ev3 Endovascular Inc., Plymouth, MN), with complete resolution of the uterine AVM on follow-up MRI (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Unilateral Onyx (ev3 Endovascular Inc., Plymouth, MN) embolization, a type of nonadhesive liquid embolic agent, for an acquired uterine AVM. A 30-year-old G1P1001 presented with vaginal bleeding 9 days following D&C for retained products of conception. (A) Color Doppler ultrasound of the uterus in sagittal plane reveals a heterogeneous, hyperechoic region within the anterior fundal myometrium extending to the endometrium with an increased vascularity. (B) DSA of the aorta with contrast demonstrates increased vascularity arising from the left uterine artery and a normal appearing right uterine artery. (C) Selective catheter angiography of the left internal iliac artery with contrast confirms an acquired uterine AVM arising from the uterine artery with arteriovenous shunting. (D) Early venous filling is also noted on delayed imaging. (E) Post-Onyx embolization angiography reveals total occlusion of the AVM. (F) Representative coronal images from follow-up MRI showing preservation of uterine perfusion, absence of a vascular malformation, and associated artifact from the Onyx embolic agent. AVM, arteriovenous malformation; D&C, dilation and curettage; DSA, Digital subtraction angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Treatment

Transcatheter Embolization

Historically, treatment for symptomatic, acquired uterine AVM required hysterectomy2; however, since its description in the late 1980s,59 TCE has provided an alternative and less invasive treatment option for patients wishing to preserve fertility. Review of articles on embolization technique utilized in the treatment of acquired uterine AVMs was performed using the criteria described above. The results of the cumulative 54 patients reviewed from 40 studies as reported as having acquired uterine AVMs are summarized in Tables 1 2 3.

Table 2. Unilateral versus bilateral approach for uterine AVM.

| Laterality | Number (N) | Requiring repeat embolization or medical treatment | Repeat embolization or medical treatment resulting in the resolution of symptoms | Requiring hysterectomy or other surgeries | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral | 22 | 4 (1 medical treatment, 3 repeat) (18.2%) | 4 | 2 (9.5%) | 2 3 7 8 9 10 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 29 31 33 35 41 |

| Bilateral | 32 | 14 (4 medical treatment, 10 repeat) (43.8%) | 9 | 6 (18.8%) | 4 5 6 9 11 12 13 20 21 24 25 26 27 28 30 32 34 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

| Total | 54 | 18 | 13 | 8 | – |

Abbreviation: AVM, arteriovenous malformation.

Table 3. Embolic agents for acquired uterine AVMs.

| Embolic agents used | Number (N) | Requiring repeat embolization or medical treatment | Repeat embolization or medical treatment resulting in the resolution of symptoms | Hysterectomy or other surgeries | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glue | 7 | 2 (both repeated with glue) | 2 | 1 (no repeat or medical treatment) | 6 27 31 41 |

| Gelfoam | 7 | 2 (repeat with coil and embosphere, danazol) | 1 (danazol-controlled bleeding) | 1 (after repeat) | 7 9 12 25 32 38 41 |

| Microsphere | 5 | 2 (implanon therapy, repeat with microspheres) | 1 | 1 (uterine AVM resection after repeat) | 7 16 17 40 |

| Coils | 6 | 1 (repeat with glue coil) | 1 | 2 (no medical treatment or repeats) | 2 8 10 18 20 21 |

| PVA | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 23 28 34 36 41 |

| Glue, Gelfoam | 2 | 2 repeat with glue/Gelfoam | 2 | 0 | 41 |

| Gelfoam, NBCA | 2 | 1 (progesterone) | 1 | 0 | 4 29 |

| Glue, coil | 2 | 1 (repeat with glue coil) | 1 | 0 | 4 41 |

| NBCA, coil | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| PVA, Gelfoam | 2 | 2 (OCP/tranexamic acid, methotrexate) | 1 (controlled by methotrexate) | 1 (due to continuous bleeding after OCP) | 11 24 |

| Coil, Gelfoam | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 26 39 |

| NBCA, microsphere | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| PVA, microsphere | 2 | 1 (Onyx, embosphere) | 0 | 1 (after repeat) | 15 22 |

| Gelfoam, microsphere | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 35 |

| PVA, coil | 1 | 1 (repeat with coil) | 1 | 0 | 37 |

| PVA, glue | 3 | 2 (both repeat with Onyx and glue) | 1 | 1 (after repeat) | 41 |

| Gelfoam, NBCA, coil | 1 | 1 (repeat with same agent) | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Onyx, NBCA, Gelfoam | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 54 | 18 | 13 | 8 |

Abbreviations: AVM, arteriovenous malformation; NBCA, N-butyl cyanoacrylate; OCP, oral contraceptive pills; PVA, polyvinyl alcohol.

Note: Gelfoam (Pharmacia and Upjohn Company, Kalamazoo, MI), Onyx (ev3 Endovascular Inc., Plymouth, MN).

The mean age of the 54 patients meeting review criteria was 33.5 ± 10.2 years (Table 1). Of 54 patients, 50 (93%) of them had a history of uterine procedures, such as D&C, cesarean section, or had a history of gestational trophoblastic tumor (Table 1). Four patients (7.4%) did not have such history; however, all of them had a history of spontaneous abortion without D&C.7 18 23 Out of the 54 patients 33 (61%) had symptoms controlled following the initial embolization. Although congenital AVMs, particularly if large, are usually approached in a methodical, stepwise manner to embolization, acquired uterine AVMs are usually encountered in the setting of menorrhagia and approached toward single-setting symptomatic hemostatic control. Nevertheless, acquired uterine AVMs may require repeat embolization for treatment and this should not be considered as a failure of embolization but rather as a requirement for additional treatments. Of the 21 patients who continued to be symptomatic following the initial embolization, 13 (62%) underwent repeat embolizations3 6 9 15 20 23 40 41 (Ghai et al included 7 cases), 5 (24%) underwent medical treatments with agents such as danazol, progesterone, combination oral contraceptive pills (OCP), implanon therapy, or methotrexate,4 7 11 24 32 2 (10%) underwent hysterectomy,2 21 and 1 (5%) underwent laparoscopic occlusion of the internal iliac arteries.27 Of the 13 patients who underwent repeat embolization, 9 cases (69%) resulted in the resolution of the symptoms. Two patients who continued to bleed after the repeat embolization therapy underwent hysterectomy,15 41 one patient underwent partial resection of the uterus,9 and one patient underwent laparoscopic resection of the AVM.40 Of the five patients who underwent concurrent medical therapy, four resulted in the resolution of the symptoms.4 7 24 32 The one patient who failed the combination OCP therapy after initial embolization underwent hysterectomy.11 Taking into consideration both initial and follow-up embolization procedures, TCE had a primary success rate of 61% and secondary success rate of 91% after repeated embolization.

Based on the literature search, there are no definitive treatment guidelines for patients who fail initial embolization. Further, there have been no studies completed comparing the effectiveness of repeat embolization versus medical therapy versus hysterectomy for persistent bleeding after initial embolization. In total, TCE and combination of medical therapy resulted in the eventual resolution of symptoms in 46 (85%) out of 54 patients without more invasive surgical procedures.

The use of a unilateral or bilateral approach for TCE must be determined in the treatment of a uterine AVM. Of the 54 patients reviewed, 22 (41%) underwent unilateral embolization and the other 32 (59%) underwent bilateral embolization (Table 2). The decision on laterality should be based on the arterial supply to the AVM determined by the angiographic appearance. After the dominant side of the artery supplying the AVM was embolized, the decision to embolize the contralateral side was largely dependent on the clinical scenario and the preference of the interventional radiologist. Of the 22 patients who underwent unilateral embolization, 1 required medical treatment following embolization, 3 required repeat embolization, and 2 required eventual hysterectomy (Table 2).2 7 15 Of the 32 of 54 reviewed patients who underwent bilateral embolization for acquired uterine AVM (Table 2), 4 required medical therapy following embolization, 10 required repeat embolization, and 6 required eventual surgery secondary to persistent bleeding.9 11 21 37 38 40 41 Although uterine AVM size was not reported, the higher rate of repeat embolization for the bilateral approach TCE cases may be speculated to reflect larger or more deeply involved lesions. The ovarian artery was embolized using gelatin sponge with symptomatic control at the time of initial TCE for two cases.4 No other cases described embolization of parasitized arteries. No controlled studies have been performed to evaluate the effectiveness of a unilateral versus bilateral treatment approach. Further, given the differences in embolic agents, AVM size and history, and clinical symptoms, no direct comparison can be made in these cases in regards to a unilateral or bilateral approach.

A variety of embolic agents and combination of embolic agents were used for treatment in the reviewed cases, and the choices of the embolic agents were largely based on the preference of the interventional radiologists. The embolic agents used in the literature are summarized in Table 3. Based on this literature search there has been no study comparing the efficacy of each embolic agent, or combinations of agents. Glue (seven cases [13%] [Ghai et al included four cases]),6 27 31 41 Gelfoam (Pharmacia and Upjohn Company, Kalamazoo, MI) (seven cases [13%]),7 9 12 25 32 38 41 coils (six cases [11%]),2 8 10 18 20 21 polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (six cases [11%]),14 23 28 34 36 41 microspheres (five cases [9%] (Halperin et al included two cases)]7 16 17 40 were the most commonly used embolic agents as single agents. There were 14 other combinations of embolic agents used in the literature (Table 3). Although oftentimes utilized for the treatment of congenital AVMs, alcohol was not described in the included articles for the treatment of the acquired uterine AVM. Despite the numerous combinations and options in embolic agents utilized, there were no significant differences in the necessity for repeat embolization amongst these techniques, given the limitations in sample size and differences in the laterality of approach.

The literature available for review is limited to the treatment of acquired uterine AVMs given its rarity. However, the clinical significance of this diagnosis underscores the importance of understanding the approaches and techniques available for its treatment. Our inclusion criteria excluded studies that did not clearly describe embolic agents, the laterality of approach, and therapeutic outcomes associated with each patient limiting the available literature to low-level evidence including case reports and retrospective studies. The follow-up period in each case report or retrospective study greatly varied from weeks to years, which may have overstated the therapeutic success rate. Finally, some of the studies included failed to clearly distinguish acquired uterine AVM from other possible pathologic entities such as retained products of conception or involution of placenta. This is not surprising given the inability in many cases for pathologic confirmation and the radiologic similarities on diagnostic imaging studies. However, from a minimally invasive treatment perspective, this may not be critical as the approach may be similar for these etiologies although possibly different for a congenital vascular lesion.

Surgical Approaches

Currently, hysterectomy is indicated only for those women who do not desire fertility preservation and have limited access to medical facilities.11 The advancement of transcatheter embolization described above and the utilization of medical therapy provide options to avoid more invasive surgical approaches. Given the success of these treatment modalities, the literature is dedicated more toward the advancement of these techniques rather than surgical approaches and hysterectomy for treatment of acquired AVMs. However, hysterectomy is an appropriate option when conservative measures have failed to prevent a life-threatening hemorrhage. Both congenital and acquired AVMs have a high propensity to bleed given the inability of these arteriovenous connections to withstand high flow and elevated pressure, so appropriate consideration must be given before surgical intervention.60 Given the acuity of clinical situations that necessitate surgical intervention and the distorted uterine tissue and anatomy created by an AVM, hysterectomy should be performed by those skilled in radical pelvic surgical techniques.60 61

Minimally invasive surgical techniques have also been performed for the treatment of uterine AVMs.62 63 64 Laparoscopic occlusion of the internal iliac arteries was successfully performed using nonresorbable clips for an acquired uterine AVM that had persistent bleeding 6 weeks following two uterine artery embolization procedures.27 Additionally, surgical ligation of the uterine arteries after TCE has been reported2 62 as well as when coupled with laparoscopic myometrial lesion resection.64 Unilateral or bilateral laparoscopic bipolar coagulation of the uterine arteries has also been performed successfully for acquired uterine AVM.63 64 These procedures were most commonly performed for persistent bleeding despite initial or repeat TCE. The role of these minimally invasive surgical techniques as a primary or secondary treatment for uterine AVM as well as in fertility following such surgeries requires further investigation.

Postprocedural Management

Among 54 TCE cases reviewed, there were no major complications. Six developed pelvic pain or cramping, which were the most common side effects reported following TCE. These were either self-limited or controlled by opioids or acetaminophen.4 7 23 35 36 38 There was also one patient with a postprocedural fever, a characteristic of postembolization syndrome, which was self-limited.35 In terms of postembolization syndrome, a 2-week course of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory should be considered following uterine artery embolization. Other reported complications of TCE include nausea and leukocytosis as well as those complications related to standard angiographic technique, such as puncture site hematoma, iatrogenic vessel dissection, and contrast-induced nephrotoxicity .65 Successful subsequent pregnancy and delivery following TCE has been described in 14 cases (Ghai et al included 4 cases).4 6 16 19 20 23 30 31 33 36 41 The effect of TCE on infertility is difficult to ascertain as the literature is biased toward those studies describing cases of a successful pregnancy following embolization. To note, TCE may be associated with an increased risk for placental abnormalities in subsequent gestations, specifically placenta accreta,66 67 and an increased awareness of this risk should be considered in future pregnancies following a successful embolization.

Following hysterectomy, routine postoperative care should include careful attention to pain control and bladder function due to adjacent radical dissection of the uterus, cervix, and parametrium. Hemostasis and coagulation will likely improve after removal of the bleeding source and abnormal tissue68; however, tortuous, dilated ovarian, uterine, and iliac vessels can remain a source for continued bleeding postoperatively despite ligation. Long-term follow-up is necessary to ensure continued hemostasis and to evaluate recurrence of the AVM.2 Embolization, used as an adjunct to hysterectomy, surgical resection of AVM, or vascular ligation has been described.2 61 In general, hysterectomy requires intensive management of pain and, for the majority of the cases, at least 1 day of hospitalization. Routine postoperative care, including monitoring of the vitals and urinary output is required. Prophylaxis against the occurrence of major thrombotic events is important. Full recovery can be expected in approximately 4 to 8 weeks following hysterectomy for an acquired AVM.

As uterine AVM remains a rare entity, no definitive guidelines are recommended for the treatment or follow-up for asymptomatic uterine AVM. In our practice, acquired uterine AVM patients are followed in conjunction between the patient's gynecologist and interventionalist. Repeat imaging is completed in our patients to confirm obliteration after treatment or when clinically indicated by persistent or worsening symptoms to evaluate for additional treatment. Incidentally discovered, asymptomatic uterine AVMs are less described in the literature; however, are followed clinically with a risk to benefit assessment for each patient individually to determine the necessity or timing of treatment.

Conclusions

The treatment for acquired uterine AVMs has evolved over time with the continued role for a hysterectomy but an emerging role for TCE. Although hysterectomy is a definitive therapy, TCE has become the initial treatment option for patients who wish to retain fertility or to avoid invasive procedures. Numerous cases of TCE providing adequate symptomatic relief have been documented with minimal side effects or complications. This literature search did not result in any comparison studies for the efficacy of each embolization material, unilateral versus bilateral embolization, or repeat embolization versus concurrent medical therapy versus surgery in recurrent bleeding after the initial TCE. Although uterine AVM is a rare entity, lessons can be learned from the experiences provided in the literature. Indeed, the protocol for TCE is evolving and numerous embolic agents have been successfully utilized with no specific agent or technique necessarily being most efficacious. The role of repeat embolization following initial embolization, as determined by persistent menorrhagia, appears indicated and is successful in most cases when pursued. Further studies directed at refining procedural protocols may be necessary to develop a more systematic algorithm of endovascular treatment options for uterine AVM; however, such studies are difficult given the rarity of this disease entity. Nevertheless, an understanding of the pathophysiology of uterine AVM and its prompt diagnosis in the symptomatic patient is of utmost importance to guide these, oftentimes emergent, therapeutic options.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Burrows P E. Vascular malformations involving the female pelvis. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25(4):347–360. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1102993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokomine D, Yoshinaga M, Baba Y. et al. Successful management of uterine arteriovenous malformation by ligation of feeding artery after unsuccessful uterine artery embolization. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35(1):183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa A, Sasaki H, Wada-Hiraike O. et al. Uterine arteriovenous fistula treated with repetitive transcatheter embolization: case report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(6):780–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molvi S N, Dash K, Rastogi H, Khanna S B. Transcatheter embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformation: report of 2 cases and review of literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akbayir O, Gedikbasi A, Akyol A, Ucar A, Saygi-Ozyurt S, Gulkilik A. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a rare cause of uterine arteriovenous malformation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39(9):534–538. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Przybojewski S J, Sadler D J. Novel image-guided management of a uterine arteriovenous malformation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34 02:S161–S166. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9940-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wijesekera N T, Padley S P, Kazmi F, Davies C L, McCall J M. Embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformations associated with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32(5):1075–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9573-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeda A, Koyama K, Imoto S, Mori M, Sakai K, Nakamura H. Progressive formation of uterine arteriovenous fistula after laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280(4):663–667. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-0981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rygh A B, Greve O J, Fjetland L, Berland J M, Eggebø T M. Arteriovenous malformation as a consequence of a scar pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(7):853–855. doi: 10.1080/00016340902971466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S K, Bergin D, Gonsalves C F, Mitchell D G. MRI detection of a female pelvic arteriovenous fistula after hysterectomy: treatment with superselective coil embolisation. Br J Radiol. 2008;81(969):e221–e224. doi: 10.1259/bjr/53820918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagga R, Verma P, Aggarwal N, Suri V, Bapuraj J R, Kalra N. Failed angiographic embolization in uterine arteriovenous malformation: a case report and review of the literature. Medscape J Med. 2008;10(1):12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chien S C, Tseng S C, Hwa H L, Wei M C. Immediate post-partum haemorrhage caused by rupture of uterine arteriovenous malformation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(3):252–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin A C, Hung Y C, Huang L C, Chiu T H, Ho M. Successful treatment of uterine arteriovenous malformation with percutaneous embolization. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46(1):60–63. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh A, Ayers K J. Uterine arteriovenous malformation following medical termination of pregnancy: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274(4):250–251. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin D W, Strand E A. Arteriovenous malformation of the uterus after a midtrimester loss: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2009;54(5):333–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halperin R, Schneider D, Maymon R, Peer A, Pansky M, Herman A. Arteriovenous malformation after uterine curettage: a report of 3 cases. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(5):445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morikawa M, Yamada T, Yamada H, Minakami H. Effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist on a uterine arteriovenous malformation. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 2):751–753. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000191584.28717.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipari C W, Badawy S Z. Arteriovenous malformation in a bicornuate uterus leading to recurrent severe uterine bleeding: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormick C C, Kim H S. Successful pregnancy with a full-term vaginal delivery one year after n-butyl cyanoacrylate embolization of a uterine arteriovenous malformation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29(4):699–701. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delotte J, Chevallier P, Benoit B, Castillon J M, Bongain A. Pregnancy after embolization therapy for uterine arteriovenous malformation. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):228. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang F W, Ding D C, Chen D C, Yu M H. Heavy uterine bleeding due to uterine arteriovenous malformations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(6):599–600. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00082b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demir B, Dilbaz S, Haberal A, Cetin N. Acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation after Caesarean section. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(2):160–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amagada J O, Karanjgaokar V, Wood A, Wiener J J. Successful pregnancy following two uterine artery embolisation procedures for arteriovenous malformation. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24(1):86–87. doi: 10.1080/01443610310001627164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kochhar P K, Sarangal M, Gupta U. Conservative management of cesarean scar pregnancy with uterine arteriovenous malformation: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2013;58(1–2):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castillo M S, Borge M A, Pierce K L. Embolization of a traumatic uterine arteriovenous malformation. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2007;24(3):296–299. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alessandrino F, Di Silverio E, Moramarco L P. Uterine arteriovenous malformation. J Ultrasound. 2013;16(1):41–44. doi: 10.1007/s40477-013-0007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy-Zaubermann Y, Capmas P, Legendre G, Fernandez H. Laparoscopic management of uterine arteriovenous malformation via occlusion of internal iliac arteries. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(6):785–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chittawar P B, Patel K, Agrawal P, Bhandari S. Hysteroscopic diagnosis and successful management of an acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation by percutaneous embolotherapy. J Midlife Health. 2013;4(1):57–59. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.109641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umezu T, Iwase A, Ota T. et al. Three-dimensional CT angiography is useful for diagnosis of postabortion uterine hemorrhage: 3 case reports and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(2):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai C C, Cheng Y F, Changchien C C, Lin H. Successful term pregnancy after selective embolization of a large postmolar uterine arteriovenous malformation. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16 01:439–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chia Y N, Yap C, Tan B S. Pregnancy following embolisation of uterine arteriovenous malformation—a case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32(5):658–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi K, Yamada T, Iwasa M, Maruo T. Successful medical treatment with danazol after failed embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformation. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):843–844. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopal M, Goldberg J, Klein T A, Fossum G T. Embolization of a uterine arteriovenous malformation followed by a twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):696–698. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00714-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarke M J, Mitchell P J. Uterine arteriovenous malformation: a rare cause of uterine bleeding. Diagnosis and treatment. Australas Radiol. 2003;47(3):302–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2003.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly S M, Belli A M, Campbell S. Arteriovenous malformation of the uterus associated with secondary postpartum hemorrhage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(6):602–605. doi: 10.1002/uog.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garner E I, Meyerovitz M, Goldstein D P, Berkowitz R S. Successful term pregnancy after selective arterial embolization of symptomatic arteriovenous malformation in the setting of gestational trophoblastic tumor. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;88(1):69–72. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan C C, Chu F, Pun T C. Treating a recurrent uterine arteriovenous malformation with uterine artery embolization. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(11):905–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Wang G, Xie F, Wang B, Tao G, Kong B. Embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformation. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013;11(2):159–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tullius T G Jr, Ross J R, Flores M, Ghaleb M, Kupesic Plavsic S. Use of three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of uterine arteriovenous malformation and follow-up after uterine artery embolization: Case report and brief review of literature. J Clin Ultrasound. 2015;43(5):327–334. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patton E W, Moy I, Milad M P, Vogezang R. Fertility-preserving management of a uterine arteriovenous malformation: a case report of uterine artery embolization (UAE) followed by laparoscopic resection. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(1):137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghai S, Rajan D K, Asch M R, Muradali D, Simons M E, TerBrugge K G. Efficacy of embolization in traumatic uterine vascular malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(11):1401–1408. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000096761.74047.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowe L H, Marchant T C, Rivard D C, Scherbel A J. Vascular malformations: classification and terminology the radiologist needs to know. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47(2):106–117. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa T. Congenital arteriovenous malformations involving the pelvis and retroperitoneum: a case report. Angiology. 1979;30(1):70–74. doi: 10.1177/000331977903000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Timmerman D, Wauters J, Van Calenbergh S. et al. Color Doppler imaging is a valuable tool for the diagnosis and management of uterine vascular malformations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(6):570–577. doi: 10.1002/uog.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gloviczki P, Duncan A, Kalra M. et al. Vascular malformations: an update. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2009;21(2):133–148. doi: 10.1177/1531003509343019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dahlgren L S, Effer S B, McGillivray B C, Pugash D J. Pregnancy with uterine vascular malformations associated with hemorrhagic hereditary telangiectasia: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(8):720–723. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grivell R M, Reid K M, Mellor A. Uterine arteriovenous malformations: a review of the current literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60(11):761–767. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000183684.67656.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rebarber A, Fox N S, Eckstein D A, Lookstein R A, Saltzman D H. Successful bilateral uterine artery embolization during an ongoing pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 2):554–556. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318193bfdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darlow K L, Horne A W, Critchley H O, Walker J, Duncan W C. Management of vascular uterine lesions associated with persistent low-level human chorionic gonadotrophin. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34(2):118–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peitsidis P, Manolakos E, Tsekoura V, Kreienberg R, Schwentner L. Uterine arteriovenous malformations induced after diagnostic curettage: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(5):1137–1151. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koyalakonda S P, Pyatt J. High output heart failure caused by a large pelvic arteriovenous malformation. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(8):66. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2011.011057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nasu K, Yamaguchi M, Yoshimatsu J, Miyakawa I. Pregnancy complicated by asymptomatic uterine arteriovenous malformation: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(4):335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albers J R, Hull S K, Wesley R M. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(8):1915–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rangarajan R D, Moloney J C, Anderson H J. Diagnosis and nonsurgical management of uterine arteriovenous malformation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30(6):1267–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fakhri A, Fishman E K, Mitchell S E, Siegelman S S, White R I. The role of CT in the management of pelvic arteriovenous malformations. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1987;10(2):96–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02577976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sellmyer M A, Desser T S, Maturen K E, Jeffrey R B Jr, Kamaya A. Physiologic, histologic, and imaging features of retained products of conception. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):781–796. doi: 10.1148/rg.333125177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katz M D, Sugay S B, Walker D K, Palmer S L, Marx M V. Beyond hemostasis: spectrum of gynecologic and obstetric indications for transcatheter embolization. Radiographics. 2012;32(6):1713–1731. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nicholson A A, Turnbull L W, Coady A M, Guthrie K. Diagnosis and management of uterine arterio-venous malformations. Clin Radiol. 1999;54(4):265–269. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(99)91165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilms G E, Favril A, Baert A L, Poppe W, Van Assche F A. Transcatheter embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformations. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1986;9(2):61–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02577901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown J V III, Asrat T, Epstein H D, Oglevie S, Goldstein B H. Contemporary diagnosis and management of a uterine arteriovenous malformation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 2):467–470. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181719f7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moulder J K, Garrett L A, Salazar G M, Goodman A. The role of radical surgery in the management of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation. Case Rep Oncol. 2013;6(2):303–310. doi: 10.1159/000351609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen S-Q, Jiang H-Y, Li J-B, Fan L, Liu M J, Yao S Z. Treatment of uterine arteriovenous malformation by myometrial lesion resection combined with artery occlusion under laparoscopy: a case report and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169(2):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y C, Liu W M, Yuan C C, Ng H T. Successful treatment of symptomatic arteriovenous malformation of the uterus using laparoscopic bipolar coagulation of uterine vessels. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(6):1270–1271. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02900-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Milingos D, Doumplis D, Sieunarine K, Savage P, Lawson A D, Smith J R. Uterine arteriovenous malformation: fertility-sparing surgery using unilateral ligation of uterine artery and ovarian ligament. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(3):735–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Calligaro K D, Sedlacek T V, Savarese R P, Carneval P, DeLaurentis D A. Congenital pelvic arteriovenous malformations: long-term follow-up in two cases and a review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 1992;16(1):100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanter G, Packard L, Sit A S. Placenta accreta in a patient with a history of uterine artery embolization for postpartum hemorrhage. J Perinatol. 2013;33(6):482–483. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soeda S, Kyozuka H, Suzuki S, Yasuda S, Nomura Y, Fujimori K. Uterine artery embolization for uterine arteriovenous malformation is associated with placental abnormalities in the subsequent pregnancy: two cases report. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2014;60(1):86–90. doi: 10.5387/fms.2013-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matteson K A, Abed H, Wheeler T L II. et al. A systematic review comparing hysterectomy with less-invasive treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(1):13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]