Abstract

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, research on stigma has continued. Building on conceptual and empirical work, the recent period clarifies new types of stigmas, expansion of measures, identification of new directions, and increasingly complex levels. Standard beliefs have been challenged, the relationship between stigma research and public debates reconsidered, and new scientific foundations for policy and programs suggested. We begin with a summary of the most recent Annual Review articles on stigma, which reminded sociologists of conceptual tools, informed them of developments from academic neighbors, and claimed findings from the early period of “resurgence.” Continued (even accelerated) progress has also revealed a central problem. Terms and measures are often used interchangeably, leading to confusion and decreasing accumulated knowledge. Drawing from this work but focusing on the past 14 years of stigma research (including mental illness, sexual orientation, HIV/AIDS, and race/ethnicity), we provide a theoretical architecture of concepts (e.g., prejudice, experienced/received discrimination), drawn together through a stigma process (i.e., stigmatization), based on four theoretical premises. Many characteristics of the mark (e.g., discredited, concealable) and variants (i.e., stigma types and targets) become the focus of increasingly specific and multidimensional definitions. Drawing from complex and systems science, we propose a stigma complex, a system of interrelated, heterogeneous parts bringing together insights across disciplines to provide a more realistic and complicated sense of the challenge facing research and change efforts. The Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS) offers a multilevel approach that can be tailored to stigmatized statuses. Finally, we outline challenges for the next phase of stigma research, with the goal of continuing scientific activity that enhances our understanding of stigma and builds the scientific foundation for efforts to reduce intolerance.

Keywords: prejudice, discrimination, disparities, connectedness, mental illness, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

Consideration of stigma, both inside and outside sociology, inevitably begins with Goffman’s (1963) classic and continues to look to this work as a source of inspiration and ideas. Yet contemporary sociological research has reconsidered its connections to original works on prejudice and discrimination, writ large, in the earlier writings of Gordon Allport and Robin Williams (Pescosolido & Martin 2007). Traditionally, the study of stigma in sociology has been attached primarily to conditions such as mental illness or HIV/AIDS, while the study of prejudice and discrimination has targeted specific status characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, poverty, or sexual orientation. However, in the period following the turn of the century, that distinction has been blurred in part by sociology’s greater recognition of other similar disciplinary lines of research, particularly psychological social psychology (Link & Phelan 2001, Major & O’Brien 2005). Signaling a move from the focus on establishing the contemporary levels of stigma, both in the United States and internationally, research over the past 14 years has begun to look more closely at the complexity of stigma; at comparisons across time, place, and substantive cases; and at novel uses (e.g., stigma of place such as neighborhoods; Keene & Padilla 2010, Kelaher et al. 2010, Sampson & Raudenbush 2004). Although removing historical lines of separation in research agendas increases the potential for theoretical elaboration and innovation, it also calls for greater clarification of concepts and measurement and a reassessment of the impact of stigma on inequality. This period, in general, also reacquainted stigma researchers with a greater consideration of the need to understand the lived experiences of those who are stigmatized, the standard assumptions underlying the roots of stigma and potential for social change, and the policy and practice implications of their research.

For stigma research to move forward, sociologists and other stigma researchers need to continue conceptual and measurement clarification as well as pursue innovative directions that define critical agendas to understand and alter the landscape of stigma. This review begins with a short survey of the contours of stigma research but returns fairly quickly to the basics of concept definition. It builds on the theoretical work but moves to consider and develop the entire stigma complex, that is, the system of interrelated, heterogeneous parts, which is composed of key concepts, basic premises, and characteristics of the stigmatization process, including stigma variants, dimensions, and interacting units. With this in mind, we outline major advances in research, with an emphasis on public stigma to balance the earlier emphasis on internal processes elaborated in the last reviews in the Annual Review of Sociology (Link & Phelan 2001) and the Annual Review of Psychology (Major& O’Brien 2005). Finally, by integrating the results of theoretical work, methodological discussions, and empirical findings over this period, we consider the contributions, limits, and new directions of stigma research.

REVIEWING THE CURRENT THEORETICAL SCOPE OF STIGMA

One factor that stands in the way of understanding the broad, deep nature of stigma and it effects lies in “naming and framing” (Brown 1995). For example, the use of the word “stigma” is not uncontested, nor is research in this area equally esteemed across societal sectors. Although most researchers do not appear to shun the term, some in the larger community reject it outright. For example, some persons with lived experience (i.e., have an illness, an event, a status, or a relationship that predisposes them to disdain) find that “stigma” does not convey the harshness of its impact, preferring “discrimination” (e.g., SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration). Similarly, Thomas R. Insel, the director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has called stigma “a victim word,” noting “discrimination is a better word for framing the issue” (original emphasis; Scheller 2014). In fact, NIMH’s movement away from this area of research in favor of a heavily molecular focus on the search for cause and cure is defended on the basis of a workgroup conclusion noting a lack of innovation and little “traction for a lot of new discoveries” (quoted in Carpenter 2005). Yet at the same time, other NIH Institutes (e.g., the Fogarty International Center) supported a pioneering effort during this period to understand stigma across many disease categories (e.g., cleft palate, as well as mental illness and HIV/AIDS), different groups (e.g., the public, employers, “people with”), and countries where little was known (e.g., the Global South; Keusch et al. 2006).

Perhaps more importantly, despite these contentious issues in public and research spheres, stigma research continued the growth documented earlier (Link & Phelan 2001).1 Both within its traditional domain of mental illness and beyond, stigma research in this period saw more studies across a wider range of topics. In health-related stigma (Deacon 2006, Weiss et al. 2006), topics expanded and had greater specificity, including multiple births (Ellison & Hall 2003), genetic testing (Tickle-Degnen et al. 2011), human papillomavirus (Waller et al. 2007), celiac disease (Olsson et al. 2009), hearing loss (Wallhagen 2010), obesity (Farrell 2011, Granberg 2011, Puhl & Brownell 2003), chronic fatigue syndrome (Asbring & Narvanen 2002), tuberculosis (Baral et al. 2007, Juniarti & Evans 2011), dementia and Alzheimer disease (Vernooij-Dassen et al. 2005, Werner et al. 2012), Parkinson disease (Tickle-Degnen et al. 2011), autism (Gray 2002), borderline personality disorder (Farrugia 2009, Rusch et al. 2006), phobias (Davidson 2005), and smoking (Bayer & Stuber 2006, Greaves et al. 2010, Pachankis 2007, Puhl & Latner 2007). Simultaneously, major work continued on more traditional areas such as mental illness (Schomerus et al. 2012), epilepsy (Austin & Shafer 2002, De Boer et al. 2008), and substance abuse (Room 2005), although the theme of greater specificity is evident (e.g., see Kanter et al. 2008 on a specific measure of depression self-stigma).

More interestingly, the social arenas in which stigma was considered swelled to include financial issues, e.g., bankruptcy (Metzl & Hansen 2014, Sullivan et al. 2006, Thorne & Anderson 2006), poverty (Reutter et al. 2009), coupon using (Argo & Main 2008); family and relationship issues, e.g., singlehood (Byrne & Carr 2005), voluntary childlessness (Park 2002), infertility (Donkor & Sandall 2007), abortion (Kumar et al. 2009), family leave (Rudman & Mescher 2013), sexual orientation (Herek 2004); the uptake of social benefits, e.g., Medicaid (Palmer et al. 2004), public housing (Stuber & Kronebusch 2004); “place,” e.g., neighborhood (Keene & Padilla 2010, Kelaher et al. 2010, Sampson & Raudenbush 2004); and crime, e.g., felony history (Behrens 2004), incarceration (Schnittker & John 2007), sexual assault (Gibson & Leitenberg 2001). A pastiche of other stigma topics addressed during this period targeted the college athlete (Simons et al. 2007), blacklisted artists during Hollywood’s Red Scare (Pontikes et al. 2010), former child soldiers (Betancourt et al. 2010), nonnative accents (Gluszek & Dovidio 2010), gambling (Horch & Hodgins 2008), stripping (Trautner & Collett 2010), suicide survivors (Cvinar 2005), hopelessness (Kidd 2007), and racial economic discrimination (Loury 2003).

Stigma research during this period also became more specific and complicated, combining considerations of stigmatized statuses across groups, in specific countries, or in specific institutions (e.g., Alvidrez et al. 2008, Collins et al. 2008, Emlet 2006, Van Hollen 2010, Wailoo 2006). In particular, mental health stigma in the military (Greene-Shortridge et al. 2007, Kim et al. 2010, Pietrzak et al. 2009) or among specific ethnic groups (Anderson et al. 2008, Gary 2005, Khazzoom 2003, Varas-Díaz et al. 2005; see Mak et al. 2007 for a review) addressed rising concerns about suicide and diversity, respectively. More international work within and across countries was completed. The mental illness research documented in the late twentieth century focused primarily on the United States and Western Europe but has now expanded to include Singapore (Lai et al. 2000), Hong Kong (Lee et al. 2005), and Ethiopia (Shibre et al. 2001), and, for example, multiple country comparisons (e.g., Brohan et al. 2010, Evans-Lacko et al. 2011, Griffiths et al. 2006, Mojtabai 2010, Pescosolido et al. 2013). This was also the case for HIV-stigma research, which continued to focus on countries of high prevalence (e.g., Haiti, Castro & Farmer 2005; South Africa, Simbayi et al. 2007) but expanded to other regions (e.g., Brazil, Abadía-Barrero & Castro 2006; China, Li et al. 2009) and multiple country comparisons (Genberg et al. 2009, Maman et al. 2009). Finally, direct comparisons among different stigmatizing conditions emerged (e.g., HIV, SARS, tuberculosis, Mak et al. 2006; depression, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, Roeloffs et al. 2003).

Conceptually and methodologically, researchers considered issues of positive stigma (Shih 2004) and resistance (Poindexter & Shippy 2010, Thoits 2011), as well as attempts to conceal stigmatized statuses (DeJordy 2008, Garcia et al. 2007, Quinn & Chaudoir 2009, Schwenk et al. 2010). These issues of resilience, empowerment, and overcoming stigma were particularly prevalent in the mental health arena, as the concept of recovery (i.e., not cure but living a full life with illness) became part of the research and policy literatures (Bockting et al. 2013, Pilgrim & McCranie 2013, Yanos et al. 2008). But recent research across a number of stigmatized statuses suggests that protest has no effect on stigma (Corrigan et al. 2001), whereas everyday resistance is often associated with high-risk health behaviors (Factor et al. 2011). Concepts of triple stigmas (e.g., mental illness, substance abuse, and criminal history; Hartwell 2004) and intersectionality (e.g., HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work; Logie et al. 2011) were developed or integrated into stigma research. More mixed methods were employed (Green 2003), and there was a greater focus on those with lived experience (Dinos et al. 2004, Lysaker et al. 2007, Ritsher & Phelan 2004, Schulze & Angermeyer 2003). Outcomes research targeted the effect of stigma on social adaptation and recovery (Clark et al. 2004, Link & Phelan 2006, Perlick et al. 2001, Yanos et al. 2008), self-esteem and related social psychological dispositions (Corrigan et al. 2006, Inzlicht et al. 2006, Lysaker et al. 2007, Major & O’Brien 2005), physiological effects (Hatzenbuehler 2009), violence (Silton et al. 2011), educational outcomes (Grollman 2012, Guyll et al. 2010, McLeod & Kaiser 2004, McLeod et al. 2012, Shifrer 2013), and even the migration of health and welfare providers in the face of stigmatized illness spread (Kohi et al. 2010). From a more medical perspective, whether stigma affected help-seeking (Kalichman & Simbayi 2003, Komiti et al. 2006, Mojtabai 2010, Schomerus & Angermeyer 2008, Sirey et al. 2001, Vogel et al. 2007) or adherence with prescribed treatments (Livingston & Boyd 2010, Tsang et al. 2010, Ware et al. 2006) continued to be a critical issue. This is no more clearly demonstrated than in research from the current period documenting the reduction of life chances about which Link & Phelan (2001) could only speculate in the earlier period. For example, mental illness is associated with a significant loss of life expectancy (in the United Kingdom, 8–17 years; Chang et al. 2011, Dembling et al. 1999). While the ravages of the disorders themselves are at issue, stigma has also been implicated in lifestyle and opportunities associated with longevity (referred to as the hidden burden of illness, Weiss et al. 2006). In fact, the focus on stigma as a cause of health disparities in population health, overall, represented a novel line of thinking in the current period (e.g., see special section of volume 103 of the American Journal of Public Health, of which Hatzenbuehler et al. 2013 is a part).

Finally, this latest era saw four additional new avenues of research. First, there was a greater emphasis on change, that is, longitudinal research at both the macro (e.g., overtime in the United States, Pescosolido et al. 2010) and micro (e.g., individuals, Lysaker et al. 2007) levels. Second, the first study of public stigma targeting children and adolescents with mental health issues (Pescosolido et al. 2007a,c, 2008a; Wright et al. 2011), and beginning research on stigma among adolescents with epilepsy (MacLeod & Austin 2003), was done. Third, some of the first evaluations of public efforts (as opposed to just clinical interventions) to reduce stigma, efforts seen as all too rare, were reported (e.g., Estroff et al. 2004, Pinto-Foltz & Logsdon 2009, Thornicroft et al. 2007, Vaughan & Hansen 2004). Last, researchers began to address the spectrum critique (i.e., that vignettes only present one portrait, usually without any reference to treatment or outcome status). In fact, McGinty et al. (2015) have documented a significant, but surprisingly modest, decrease in the percentage of the population endorsing stigma items when vignettes that mentioned treatment, compared with those that did not, were provided as the stimulus.

A STIGMA PRIMER: BASIC CONCEPTS, PROCESS COMPONENTS, PREMISES, AND VARIANTS

Basic Concepts

“Stigma,” as used in the research literature, is a global referent category. It is not a singular entity (Reidpath & Chan 2005), a static phenomenon (Goffman 1963), or an either/or experience (Link & Phelan 2001). Not surprisingly, given this conceptual ambiguity, the scope of stigma research across disciplines, characteristics, and periods has produced a definitional morass (Livingston & Boyd 2010). As Dembling et al. (1999) note, there is a great deal of variation in usage of terms essentially targeting the same social phenomena. Pursuing Link & Phelan’s (2001) and Major & O’Brien’s (2005) aim to theoretically organize the stigma concept and stigma research, we extend the focus to conceptual clarity in this section.

In Table 1, we attempt to distill the primary elements in this area by listing the most commonly used terms in contemporary stigma research. This list is not exhaustive or in agreement with any attempt to bring together or adjudicate the approach of any one discipline, community, or study. Rather, we aim to better understand stigma research by clarifying what kinds of stigmas, what kinds of individuals, and what kinds of consequences have been studied.

Table 1.

Theoretical building blocks of stigma research

| Basic concepts | |

| Stigma | A deeply discrediting attribute; “mark of shame”; “mark of oppression”; devalued social identity |

| Stigmatization | A social process embedded in social relationships that devalues through conferring labels and stereotyping |

| Labels | Officially sanctioned terms applied to conditions, individual, groups, places, organizations, institutions, or other social entities |

| Stereotypes | Negative beliefs and attitudes assigned to labeled social entities |

| Prejudice | Endorsement of negative beliefs and attitudes in stereotypes |

| Discrimination | Behaviors that act to endorse and reinforce stereotypes, and disadvantage those labeled |

| Stigma characteristics | |

| Physical | Of the body, e.g., physical disabilities |

| Character | Indicating moral weakness, e.g., criminal, mental illness |

| Status | A position in society; often used with ascribed characteristics, e.g., race/ethnicity |

| Discredited | Already known or immediately evident; “marks” that are visible or not concealable |

| Discreditable | Neither known nor immediately perceivable; “marks” that are invisible or concealable |

| Changeable | Subject to direct attempt to change by individual or group |

| Fixed | Subject to change only by changing the social meaning of the “mark” |

| Target variants | |

| Experiential | |

| Perceived | Belief that “most people” will devalue, discriminate the stigmatized |

| Endorsed | Expressed agreement with stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination |

| Anticipated | Expectations of experiencing prejudice and discrimination among the stigmatized |

| Received | Overt behaviors of rejection and devaluation experiences of negative interactions |

| Enacted | Behaviors of differential treatment by stigmatizers |

| Action-oriented | |

| Self-stigma | Internalized acceptance of stereotypes and prejudice |

| Courtesy stigma | Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination by association with marked groups |

| Public stigma | Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination endorsed by the general population |

| Provider-based stigma | Prejudice and discrimination voiced or exercised, consciously or unconsciously, by occupational groups designated to provide assistance to stigmatized groups |

| Structural stigma | Prejudice and discrimination by policies, laws, and constitutional practice; also called institutionalized stigma |

Stigma, proper, is the mark, the condition, or status that is subject to devaluation (Goffman 1963, Hinshaw 2006, Sartorius 2007). Stigmatization is the social process by which the mark affects the lives of all those touched by it. Both are dependent on four general and essential process components (Link & Phelan 2001). Stigma requires (a) distinguishing and labeling differences, (b) associating human differences with negative attributions or stereotypes, (c) separating “us” from “them,” and (d) experiencing status loss and discrimination. Four essential premises underlie these requirements. First, stigmatization is dependent on core concerns of the sociological enterprise—power and the ability to stratify tangible and intangible resources (Link & Phelan 2001, see also Scambler 2009). Three additional premises remind us of Goffman’s original premise and raise the conceptual status of two other commonly accepted and often mentioned bases. These are as fundamental to understanding stigma as they are to the core principles of sociology. The second fundamental premise is stigmatization can be enacted only through social relations, as Goffman (1963) originally noted. Although individuals may anticipate rejection and exclusion, they are made “real” only as they experience them in social interaction. Third, stigmas are shaped and reshaped in the particular cultural configurations that arise in social context, i.e., time and place. Stigmas reflect the fault lines in a society at any one point and are as artificial and subject to change as national boundaries on a world map. Although widely acknowledged (but little studied), the role of context in shaping the lifestyles and life chances of individuals defines the nature of power and inequality, as well as normative determination of the good, the deserving, or the moral, and by contrast, the bad, the undeserving, and the immoral. As a premise, it makes explicit the structuring of stigmatization through the kind of reciprocal influence of structure and process, the individual and the societal, and history and biography that is the foundation of the sociological perspective (e.g., Coleman 1986, Mills 1959, Tilly 1984). The fourth and final premise is that all components of stigma exist as a continuum. Most commonly seen as part of a spectrum (Link & Phelan 2001), responses can be mild or harsh, whether from the stigmatized or the stigmatizer, or from individuals, groups, organizations, institutions, or an entire society.

As Goffman (1963) notes, stigmas can be a mark of the body, of character, or of a status (we replace his term for this, “tribal stigma,” with more contemporary language; see Pescosolido 2015). Stigma “signatures,” as Fiske (2011) calls them, may be immediately evident (discredited) or not (discreditable), and they may be changeable or fixed (Table 1). As social psychologists have demonstrated, each of these characteristics may have a differential impact on outcomes. For example, Quinn & Chaudoir (2009) found that among 300 individuals with over a dozen concealable (i.e., discreditable) stigmas, intraindividual processes associated with stigma concerns were associated with both psychological distress and health outcomes.

In fact, this period of research continued the movement away from the global approach to stigma as a generalized mark to more specific categorizations where appropriate. The findings were important. They raised issues of the underlying meaning of responses to global measures and provided evidence for new directions for stigma reduction efforts. For example, in the area of mental health and illness, the move from using statements about mental illness to vignettes that captured psychiatry’s categorization of specific problems (i.e., diagnoses) revealed a severity gradient in line with the spectrum issue discussed above. Empirical findings in the United States suggested that for both children and adults stigmatizing responses flow along a gradient. The percentage of respondents endorsing stigmatizing responses increased from “troubled person” to depression to schizophrenia to alcohol dependence and, finally, to drug dependence (Corrigan et al. 2009; Pescosolido et al. 2008a, 2010; Silton et al. 2011). The depression-schizophrenia gradient also held across five European nations (Pescosolido et al. 2008c; see also Barry et al. 2015). For children, a clear split appeared between mental health and nonmental health issues. “Daily troubles” and asthma elicited the fewest number of negative responses, followed by ADHD and depression, for which the highest number of negative responses switches between the two depending on the type of prejudice reported (Pescosolido 2013, Pescosolido et al. 2008a). Perhaps more importantly, although most respondents in the National Stigma Study-Children (NSS-C) could identify ADHD, fully one-quarter of them did not identify (i.e., label) it as a mental illness (McLeod et al. 2007). The implications of these latter findings in terms of validity of responses and how the public would respond to campaigns to “end” stigma toward children with mental illness, for example, are potentially profound.

In sum, a difference is translated into a marked, devalued distinction. Through a culturally constituted process, the mark works to advantage or disadvantage others through social interactions with individuals, groups, organizations, and institutions. Stigma is conferred through labels, which are officially sanctioned terms encoded by official agents of social control (e.g., “mentally ill” by the medical profession, “criminal” by the justice system) or by others informally (e.g., “fat”). These labels produce stereotypes (i.e., negative beliefs and attitudes assigned to social entities thus labeled), with variable levels of negative social consequences of prejudice (endorsement of stereotypes) and discrimination (differential and disadvantaged treatment of the stigmatized). In other words, stigma represents the intersection of cultural differentiation, identity formation through social interaction, and social inequality.

Variants

A good deal of the confusion in stigma research emanates from differences in targets of the research. As part of the critique that stigma is an “underdefined and overused concept” (Manzo 2004), clarification of target variants asks the question, What is being studied? Here we define two categories of variants—experiential variants and action variants—which, when cross-classified, reveal the myriad of work falling under the canopy of stigma. Table 1 lists the basic variants under these two categories.

The first category targets how a stigma is experienced.2 Perceived stigma represents agreement with a statement that prejudice and discrimination exist toward a labeled group. It can be asked of the stigmatized or the potential stigmatizer. It does not necessarily assume an individual’s agreement with a stigmatizing statement. For example, Sirey et al. (2001) asked nearly 100 individuals newly diagnosed with depression about their perceptions of devaluation and discrimination of individuals with mental illness. They found that younger patients perceived more stigma; however, only older patients’ perceptions translated into a discontinuation of treatment within three months. Anticipated stigma refers to individuals’ or groups’ expectations that others will devalue and discriminate against them. For example, among individuals with a family member experiencing a first-episode psychosis, fear of the official label of mental illness was implicated in a longer duration of untreated psychosis (Franz et al. 2010; see also Lee et al. 2005 on schizophrenia in China, Quinn & Chaudoir 2009 on depression in the United States, Yebei et al. 2008 on HIV/AIDS in Kenya). Among college students, the level of anticipated self-stigma had a direct influence on their predisposition to seek psychological help if confronted with mental health problems (Vogel et al. 2006). Endorsed stigma is expressed agreement with existing stereotypes. Again, it can be asked of the stigmatized [e.g., do they agree that most people with the (status/condition) are dangerous, even if they do not apply it to themselves] or the potential stigmatizer. Endorsed stigma represents one of the most commonly researched variants of stigma (Pescosolido 2013). Received stigma focuses on the stigmatized, asking whether they have personally experienced prejudice and discrimination. Finally, enacted stigma occurs when individuals behave in a way that prejudices or discriminates against the stigmatized (i.e., differential treatment).

These distinctions, though perhaps finely granulated, become important in moving stigma research forward. For example, in a study of people living with HIV in China, more than half reported discrimination and anticipated stigma, and over three-quarters reported self-stigma (Li et al. 2008). Similarly, Schomerus & Matschinger (2009) documented that endorsed stigma (measured by a desire for social distance from those with depression) decreased individuals’ willingness to seek psychiatric treatment, but their anticipation of either prejudice or discrimination did not.

Closely related to these experiential variants is a second class of distinction commonly used in the research literature that examines who gives or receives stigma, that is, action variants. Self-stigma is faced by the stigmatized, who accept assessments of lower value or worth (Boyd Ritsher et al. 2003, Watson et al. 2007). In fact, the large research literature on stereotype threat is based on the idea that stigmatized individuals are aware of expectations and act in ways that reinforce prejudice and stereotypes (reviewed in Major & O’Brien 2005). For example, Yanos et al. (2008) found that internalized stigma (both perceived and endorsed) among individuals with schizophrenia affected their sense of hopelessness and eventually their inability to recover (i.e., living a full life in spite of illness, not to be confused with cure; Pilgrim & McCranie 2013).

Courtesy stigma is stigma “by association” (Ostman & Kjellin 2002). Although individuals themselves do not have the mark, they live with, work with, or otherwise have a proximate social relationship with individuals or groups that do. Because of this social proximity, they too are subjected to devaluation through suspicion of having played a role in cause or the lack of ability to help. Both individuals who have strong ties to stigmatized groups or individuals and those that have occasional interactions are subject to this contamination (Pryor et al. 2012). Courtesy stigma has been most commonly reported by close family and other relatives (Angermeyer et al. 2003, Corrigan & Miller 2004, Koro-Ljungberg & Bussing 2009). However, Pontikes et al. (2010) reported that “mere association” with coworkers who had been blacklisted during the Red Scare reduced artists’ chances of finding employment. Even within the medical prestige hierarchy, psychiatrists encounter stigmatizing responses from other health care providers (Sharfstein 2012), and the resources devoted to mental illness have long been disproportionately low compared with the magnitude of prevalence (US Department of Health & Human Services 1999).

Public stigma attempts to map the levels and nature of stigma in the general population. It is sometimes referred to as community or cultural stigma (Quinn & Chaudoir 2009). Public stigma marks the nature of the contextual climate of prejudice and discrimination in time and place and is the subject of some of the earliest stigma studies, with more reports of change over time than other areas (Pescosolido & Martin 2007). Despite scores of different designs, respondent groups, measures, and analytic models, results show a remarkable consistency in overall scientific conclusions. Levels of public stigma around mental illness remain high, although over the recent period, the public in the Global North (where most research exists) has become more sophisticated in its understanding and more open to recognition and disclosure. Within and across Western nations, most of the public has received, and at least tacitly endorses, ideas about the severity of mental illness and accepts its underlying causes as being in the same realm as other illnesses. They reject old etiological notions locating mental illness in individual weakness and failures and report that treatment should be sought (Pescosolido et al. 2013).

The classic sociological debates about the power of behavior versus the power of labels have been settled; both have independent effects on prejudice for children, adolescents, and adults (Martin et al. 2000, 2007; Silton et al. 2011). Sociodemographics show little consistent effect on public stigma, with contact (i.e., knowing someone with mental health problems) as the most consistent association with lower levels of prejudice (Conner et al. 2009, Couture & Penn 2003; on sociodemographics see Livingston & Boyd 2010, Pescosolido 2013). Most notably, however, public acceptance of modern medical and public health views of mental illness appears to be coupled with a stubborn persistence of negative opinions, attitudes, and intentions (Angermeyer & Matschinger 2005, Pescosolido 2013, Pescosolido et al. 2010, Phelan 2005, Read et al. 2006, Schomerus et al. 2012). In fact, according to Phelan and colleagues (Phelan 2002, Phelan et al. 2006), the focus on neurobiological attribution has had complex, mixed, and even contradictory effects. Endorsing genetic attributions seemed to increase the public’s tendency to support general recommendations for help-seeking but was also associated with only specific types of help-seeking (e.g., endorsing hospitals and prescription medications, but not physicians, psychiatrists, or nonmedical mental health professionals) and with greater pessimism on the efficacy of mental health services (Schnittker 2008). Most importantly, Phelan (2005) suggested a backlash effect on tolerance. Genetics were often significantly associated with higher, not lower, levels of stigma, perhaps because the mark conveyed a sense of permanence, having effects that live on in families past the time of any one individual.

Finally, the last two experiential variants began to gather more traction during the recent period. Provider-based stigma targets individuals and institutions designated to assist the stigmatized (e.g., Li et al. 2007). As Sartorius (2007), among others, has noted, health care workers commonly use stigmatizing words, hold stereotypes about certain kinds of patients, refuse to treat some illness or injury directly in their path (as in the early HIV epidemic) or individuals outside their purview (e.g., refusing to treat individuals with mental illness in emergency rooms or intensive care units; see, for example, Ay et al. 2006, Compton et al. 2006, Dunn et al. 2009, Ross & Goldner 2009, Schulze 2007, Surlis & Hyde 2001). Once considered an almost heretical claim without scientific base, the current period found a greater acceptance of the idea, long held by consumers in psychiatry and certainly by Goffman (1961), that treatment institutions often perpetuate and sometimes worsen a number of experiential and action variants of stigma. In this period, concerns that provider-based stigma in medical school translates to high levels of suicide among medical students became more visible (e.g., Chew-Graham et al. 2003, Schwenk et al. 2010).

Structural stigma broadens this concern from individuals to organizations and institutions more generally. According to Corrigan et al. (2004), structural stigma includes “policies of private and governmental institutions that intentionally restrict the opportunities of people” and “policies of institutions that yield unintended consequences that hinder the options of people” (p. 481; emphasis added). In their case, mental illness was the target condition but these concerns have been raised historically and contemporarily in the case of many stigmatized diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, leprosy), for stigmatized groups (Wailoo 2006 on African Americans), and for recipients of welfare benefits, broadly defined (Stuber & Kronebusch 2004). From Jim Crow laws, to restricted voting or running for elective office, to little newspaper coverage, to the contemporary lack of parity in reimbursement for the treatment of mental illness, many institutions prohibit, in policy or in practice, stigmatized individuals from participating in civil society (Burns 2009, Corrigan et al. 2005, Klin & Lemish 2008, Mechanic 2008, Sartorius 2007). In fact, in many areas, the shift to a preference for “discrimination” over “stigma” represents a reaction that opportunities gained or denied through institutional access, not sentiment, are the preferred target for change. For example, in Yang et al.’s (2014) examination of Chinese immigrants being treated for mental illness, the most important aspect of stigma reported was being blocked from the accumulation of financial resources. What “mattered most” was structural stigma (or in the race tradition, institutional discrimination) even as individuals experienced a “deprecated sense of self ” (Yang et al. 2014, p. 84).

STIGMA AS A MULTIDIMENSIONAL CONCEPT: THE EXAMPLE OF PUBLIC STIGMA

As Rosenfield (1997) had alluded to earlier with regard to the centrality of stigma in debates about labeling theory, the reality of stigma-related concepts and variants is more complex than either proponents or critics conceptualize. To this point, we have examined concepts and their definitions. In this section, we focus more narrowly on one concept as a matter of necessity given that complexity. We use the public stigma of mental illness as an exemplar of yet another concern that received some attention in the period under review.

Contemporary research has examined a wider variety of stigma-related dimensions, including intolerance, exclusion, fear, and mistrust of persons, compared with earlier times (Pescosolido et al. 2007b). Yet studies rarely employ more than one or two of these dimensions. No single dimension of public stigma is uniformly accepted as the best way to capture this construct, and combined with real limits on time, resources, and respondent burden, studies tend to rely on one or another dimension or on a global scale designed to capture many of these dimensions. More importantly, this is where the development of disciplinary traditions that mark conditions or statuses has diverged most, decreasing the accumulation of findings across areas in which stigma is present. Indeed, the consistency of stigma findings reported above is remarkable given that most studies use a diverse but limited range of dimensions to capture public prejudice and behavioral dispositions.

We do not support a search for a single “best” measure of public stigma even as we bemoan the inability to build a replicated set of findings. However, current strategies miss the nuanced nature of stigma and fail to help answer questions such as, What kind of prejudice and discrimination are associated with a particular mark? Are there unique ramifications of having one type of mark versus another? We contend that considering multidimensionality has the potential to advance the continuing inquiry surrounding stigma. Here we outline several possible dimensions that have been called stigma, including social distance, traditional prejudice, exclusionary sentiments, negative affect, disclosure, and dangerousness (Pescosolido et al. 2010). Although parallels can be and are created for any mark, we focus not only on public stigma, but on the stigma of mental illness, for which multiple dimensions have been recently examined. These are defined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dimensions of public stigma

| Stigma dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Social distance | Desire to maintain an interactional detachment from persons with discredited conditions and/or statuses or who occupy stigmatized statuses |

| Traditional prejudice | Preconceived unfavorable judgments toward persons with discredited conditions and/or statuses or who occupy stigmatized statuses |

| Exclusionary sentiments | Willingness to prohibit persons with discredited conditions and/or statuses, or who occupy a stigmatized condition and/or status, from participating in major social roles |

| Negative affect | Anticipation of unpleasant emotional reactions as a consequence of direct contact with a person with a stigmatized condition and/or status or who occupies a stigmatized condition and/or status |

| Treatment carryover | Belief that public knowledge that an individual has received medical or psychological treatment for a stigmatized condition and/or status reduces the status of that individual in the larger community |

| Disclosure carryover | Belief that admission to having a discreditable condition and/or status will engender negative responses from members of the larger community |

| Perceptions of dangerousness | Fear that persons with discredited conditions and/or statuses, or who occupy stigmatized conditions and/or statuses, are likely to engage in violent or menacing behavior toward themselves or toward others in the community |

Social Distance

Perhaps the most popular operationalization of the stigma of mental illness is a desire for social/interpersonal distance. This approach is derived from Bogardus’s (1959) classic work on the reluctance of majority groups to interact with members of devalued racial and ethnic groups. Arguably, most empirical studies of the stigma of mental illness have utilized this approach (e.g., Link et al. 1999, Pescosolido et al. 2010). The logic of this dimension lies in providing venues or roles in which the potential stigmatizer would accept or reject social interaction with either the general category of “persons with” or, in the case of the US National General Social Survey studies, a vignette character who meets criteria for specific mental health problems. Questions such as these ask about the willingness of individuals to “have (name) as a neighbor” or “spend time socializing with (name).” Other roles/venues include child caregiver, friend, coworker, or “have (name) marry someone related to you.”

Traditional Prejudice

Although social distance may be the most prevalent dimension employed in stigma research, traditional prejudice is the least consistently applied dimension in the area of mental illness. The concept of traditional prejudice derives mainly from the early literature on the racial attitudes of Americans (Fredrickson 1971, Hyman & Sheatsley 1956). Variously referred to as traditional prejudice, old-fashioned prejudice, and Jim Crow racism, these items captured adherence to the belief that blacks are the categorical intellectual inferiors of whites (Bobo et al. 1997, p. 16). A key feature of this form of prejudice is that the stereotypical negative characterization is applied uniformly to all members of the devalued group in the form of stereotypes. In mental illness research, these stereotypes have been adapted in various ways (see, for example, Couture & Penn 2003), for example, asking whether individuals with mental illness or specific disorders are as intelligent, productive, or trustworthy as anyone else, or are unpredictable.

Exclusionary Sentiments

Also drawing from research on race attitudes is a stigma dimension that taps into the willingness to exclude persons with mental illness from the full benefits of citizenship, i.e., to deny them the right to engage in certain activities or roles commonly taken for granted by others. These include holding public office and being a parent, supervisor, or teacher. Perhaps the most traditional measure here refers to the field of equal employment opportunity, which asks whether people with mental illness, if qualified for a job, should be hired like any other person. If, as Goffman argues, stigma is enacted in social relationships, as many contemporary policy makers (e.g., Carter et al. 2013) believe, then inclusion is a key to destigmatization, and providing empirical evidence on dimensions that are critical in social interactions would appear to be key.

Negative Affect

Simply stated, negative affect captures popular public views of how uneasy individuals felt or would feel in an interaction with a person with mental illness (Corrigan et al. 2003, Link et al. 2004). Are individuals marked by a stigma hard to talk to? Does being around stigmatized individuals make individuals feel uncomfortable or nervous?

Treatment Carryover

This stigma dimension represents an example of what Link et al. (2004) characterize as the status loss/discrimination component of stigma. It is also what others have examined, in various forms, in an attempt to understand the link between anticipated or perceived stigma and the willingness to seek help (e.g., Quinn & Chaudoir 2009, Yebei et al. 2008). Treatment carryover taps into public expectations that persons with discredited conditions or statuses will occupy a devalued position in the community as a result of receiving treatment or other forms of social assistance, subjecting the stigmatized individual to official labeling and public disclosure. These in turn translate into discriminatory treatment by others in the community, including providers. For example, treatment carryover targets concerns that getting treatment would make a person an outsider in the community, and that letting others know about receiving treatment would result in the loss of friends, or would limit opportunities, no matter how much an individual might otherwise achieve.

Disclosure Carryover

The risks associated with disclosure, though always a topic of stigma research (e.g., issues of “passing”), have taken on renewed interest, especially at the individual level where the effects of disclosure and the conditions under which it is applied have a positive or negative effect (e.g., in the context of close ties, or largely supportive networks). Disclosure carryover has been examined not only in mental illness but in areas such as infertility and HIV/AIDS (Chaudoir et al. 2011, Corrigan & Rao 2013, Martins et al. 2013, Rudolph et al. 2012, Wade et al. 2011). Thus, this dimension focuses on the negative consequences of disclosure. Asking whether the individual or the family would be better off keeping the situation a secret, whether they should feel embarrassment or shame, and whether they have little hope of being accepted in the community if the situation is disclosed all tap into this dimension.

Perceptions of Dangerousness

Typified in the work of Link and his associates (see, for example, Link et al. 1999, Pescosolido et al. 1999, Phelan & Link 1998), this stigma dimension is based in the public’s fear that persons with mental illness represent a threat of potential violence to self and others, are frightening, and represent a public nuisance or threat. Although this may not directly translate to other stigmas, parallels include physical (e.g., in tuberculosis, HIV) or social contagion (e.g., criminal behavior). Indeed, the issues of dangerousness and coercion are particularly important theoretical and policy issues in the area of mental health (Pescosolido 2011, Torrey 2011).

Implications of Dimensionality

The issue of dimensionality raises fundamental questions about the nature of stigma. For example, what exactly does the mark produce in terms of prejudice and discriminatory predispositions? Similarly, when depending on only one or two items, on a unidimensional global scale, or on measures of multiple dimensions, what is the potential for understanding the complexity of stigma or narrowing the targets of social change? Targeting the multidimensionality of stigma begins to open up our understanding of how stigma attaches to societally constructed differences.

Our own research examining cross-national levels of public stigma in the Stigma in Global Context–Mental Health Study (SGC-MHS) (Olafsdottir & Pescosolido 2011; Pescosolido et al. 2008c, 2013) was forced to confront this issue of multidimensionality in the face of a history of so many studies, with so many ways of measuring public prejudice toward mental illness. Unlike many other studies with the kinds of logistic restrictions noted above, we were able to use a vignette structure with specific referents (schizophrenia and depression) in face-to-face interviews. Across nations, we began with a simple set of questions: What engenders the most negative reaction to people who are not labeled but who, essentially, meet diagnostic criteria for major mental illnesses? Is there a backbone of stigma, that is, a set of items that, no matter the national context, elicits a prejudicial response from a majority of respondents? Taking this approach raised an analytic challenge. Not surprisingly, items in many of the batteries usually employed did not scale the same way across countries. With few solutions offered in the methodological literature, we pursued an unusual approach that provided some novel insights.

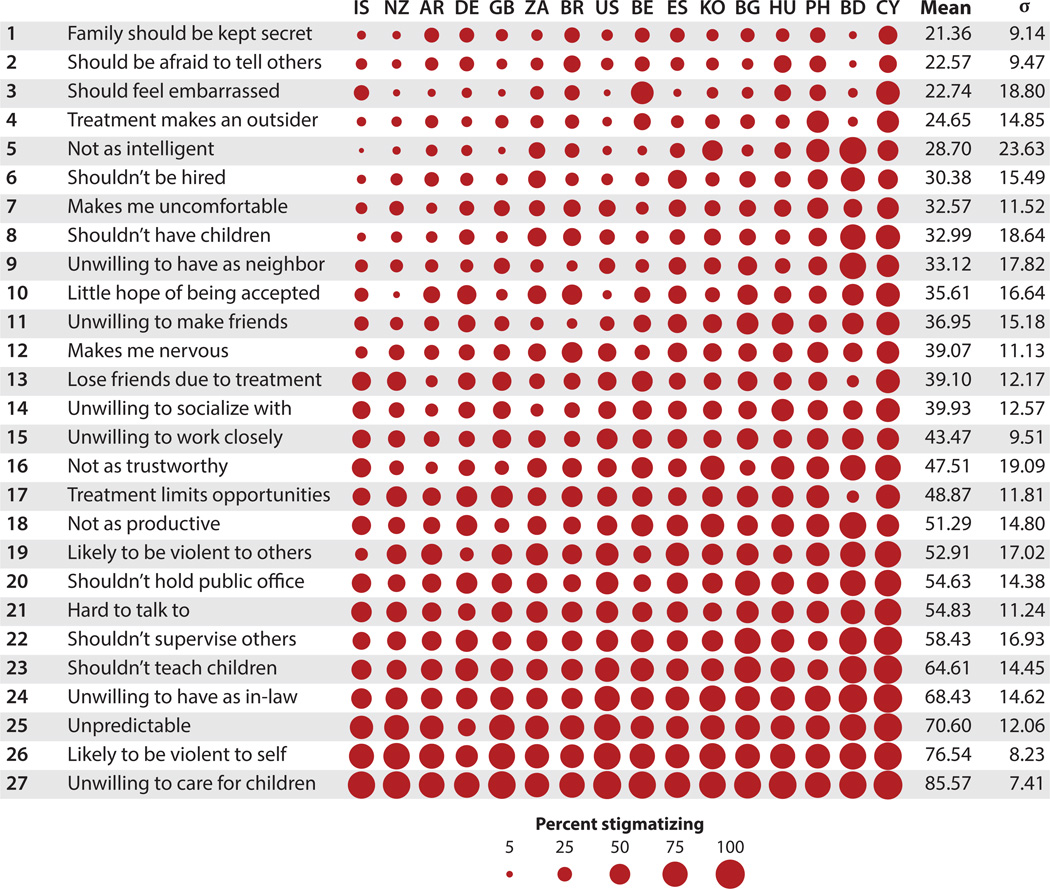

Using a simple exploratory data approach, we considered all items from six dimensions (all but dangerousness; Table 2). Figure 1 presents the levels of stigmatizing responses when individuals in a nationally representative sample within each country are presented with an unlabeled scenario describing individuals meeting psychiatric criteria for schizophrenia. Individuals received only one vignette and assignment was random. With the largest circles indicating higher percentages of agreement with stigmatizing statements within each country and item, five items were found to be endorsed by two-thirds or more of respondents across all countries. These items are numbered 23 through 27: rejecting the individual as a child care provider, having a potential for violence toward self, being unpredictable, rejecting the individual’s marriage into the respondent’s family, and excluding the individual from teaching children. These five items tap various dimensions of stigma described above, in essence, blowing up the standard scale approaches. They represent the backbone of stigma and reveal much about the core of concerns about the mark of mental illness. The next group, on the other hand, is quite large, with 15 items (Items 7–22) and a greater range in percentages. The lowest levels of public stigma (Items 1–6) are associated with disclosure (e.g., secrecy), treatment carryover (e.g., outsider), and basic civil rights (e.g., hire if qualified). These items also show greater differences across countries. Finally, in results not shown here, indicators of ignorance or misinformation reveal even lower levels of stigma (see Pescosolido et al. 2013).

Figure 1.

Percentage of individuals in 16 countries endorsing public stigma items. Schizophrenia vignette, from the Stigma in Global Context-Mental Health Study (SGC-MHS, N = 6,542). Adapted and reprinted with permission from Pescosolido et al. 2013.

Thus, even in countries with relatively more accepting cultural climates (e.g., Iceland, New Zealand), issues that deal primarily with intimate settings (the family), vulnerable groups (children), or self-harm elicit the highest levels of negative response. A secondary core around those issues targets the unwillingness to see individuals with mental illness in positions of authority or power (work supervisors, public officials), and an uneasiness about how to interact with or whether to fear violence from individuals with mental health problems. Issues of disclosure (secrecy, embarrassment), basic civil rights (hire if qualified), competence (intelligence), interactions in less intimate social venues (neighbor, friend), or any measures of misinformation seem to be of lower concern (Pescosolido et al. 2013).

In sum, it seems that a consideration of the multidimensionality of stigma holds promise for further elaborating the nature, roots, and effects of stigma. Both in the United States and elsewhere, research using a more multidimensional approach has upended traditional assumptions about the nature of stigma and directions for change (e.g., Quinn & Chaudoir 2009). Yet such an approach is not without its problems. For example, this approach continues to raise, rather than eliminate, debatable theoretical questions. Is the endorsement of dangerousness an outcome of holding a stereotype or is it a stereotype in itself? More importantly, does the theoretical status of these attitudes matter? Our answer, at present, is, “That depends.”

Taking the case of attributions reveals the contingent nature of the answer. Is ignorance a dimension of stigma or a root cause? On the one hand, the example of mental illness shows that the typical antistigma campaigns by major advocacy groups in post–World War II United States argued that prejudice and discrimination arise from ignorance (e.g., misinformation, stereotypes). Once the public was educated, stigma would dissipate. In fact, many antistigma campaigns, no matter the condition or status, target education and awareness. Research during the contemporary period, as illustrated above, showed little connection empirically between knowledge and prejudice (Pescosolido et al. 2010, Schomerus et al. 2012). At least in the area of mental illness, continuing to focus on education likely represents a waste of scarce and valuable resources that might be devoted to reducing prejudice. On the other hand, one could interpret these findings on mental illness in light of the long tradition of antistigma efforts on this condition. Putting these findings in historical context may be read to say that early-stage efforts have in fact worked. It is possible to eliminate ignorance and/or misinformation. However, this approach is insufficient to eliminate prejudice and the predisposition to discriminate.

THE STIGMA COMPLEX: EVIDENCE, EFFORTS, AND GAPS

That stigma is complicated should be, fortunately or unfortunately, clear. What is it about a stigmatized condition or status that produces ignorance, intolerance, and rejection? Questions of causality exist within a very intricate, interrelated system. In response, researchers have called for a more synergistic view (e.g., see Evans-Lacko et al. 2011 on the “virtuous cycle,” Pachankis et al. 2014 on the “vicious circle”). Stigma persists, even as the cultural attributions that underlie stigma processes are transformed (e.g., from racial weakness, to culture of poverty, to permanent medical pathology; Hansen et al. 2014). There are unintended consequences (the backlash effect of genetics on mental illness stigma, Phelan 2005), and paradoxes (network support both enhanced and withdrawn by family, Perry 2011). However, such complexities are not unfamiliar to social scientists, for example, Tilly’s (1984) or Coleman’s (1986) sociological views of macro- and microstructural effects or Ostrom’s (2009) political science–based framework for understanding and affecting environmental sustainability.

In general, the social and natural sciences as well as the health sciences (e.g., medicine, public health) have moved to a systems science approach (B.A. Pescosolido, S. Olafsdottir, O. Sporns, B.L. Perry, E. Meslin, et al., unpublished manuscript). As defined by Luke & Harris (2007, p. 357), complex systems “are made up of heterogeneous elements that interact with one another, have emergent properties that are not explained by understanding individual elements of the system, persist over time, and adapt to changing circumstances.” Bascompte’s (2009, p. 419) claims that conceptualizing, measuring, and manipulating interconnections among molecular, individual, family, and community systems allow the discovery of “generalities among systems that, despite their disparate nature, may have similar processes of formation and/or similar forces acting on their architecture.”

A stigma complex requires a systems approach to understand the complicated nature and effects of stigma. We define the stigma complex as the set of interrelated, heterogeneous system structures, from the individual to the society, and processes, from the molecular to the geographic and historical, that constructs, labels, and translates difference into marks. In turn, reactions from the internal to individual to those by even remote association, to a cultural bundle of prejudice (i.e., values, beliefs, attitudes, intentions) and discrimination (from other individuals, organizations, and institutions) are produced. This cultural bundle both shapes and is shaped by larger contexts that attempt to reduce them and subject them to larger, often unacknowledged, feedback loops, as well as intended and unintended consequences.

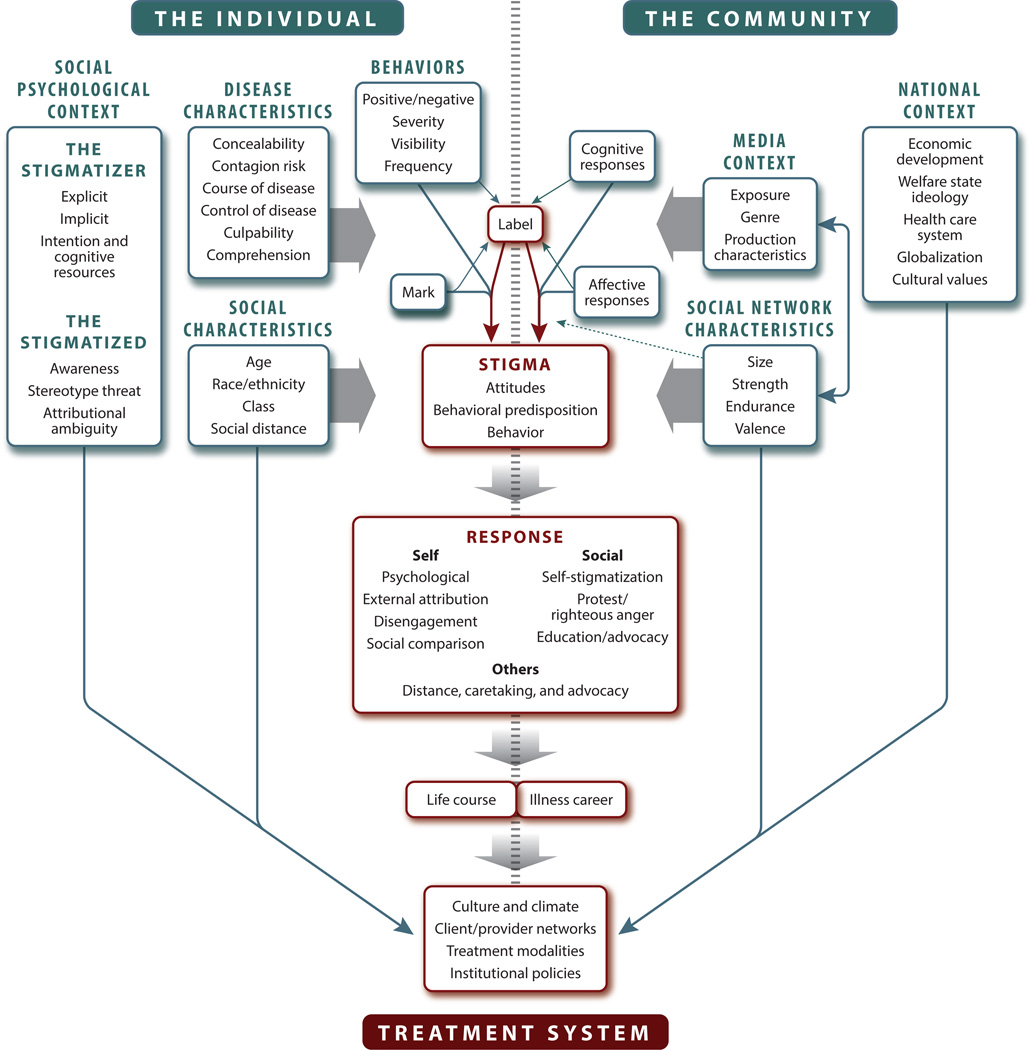

Although not initially cast in complex and systems science, an attempt for mental illness brought together theoretical insights from micro-, meso-, and macro-level research during the period under review (see also Jacoby & Austin 2007 on internalized, interpersonal, and institutional). The Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS) brought together a range of expertise from the disciplines and theories that have been useful to date (e.g., labeling theory, social network theory, limited capacity model of media influence, social psychology of prejudice and discrimination, and theories of the welfare state).

In essence, the FINIS (Pescosolido et al. 2008b) is a systems science approach. The rationale for FINIS lies in evidence, reviewed here, that stigma emanates from many societal and individual systems whose interconnections cannot be divorced from one another. They coexist in a dynamic relationship in which there is an interplay across, for example, the media, the community, and the individual. As Luke & Stamatakis (2012) point out, research that does not consider the “system,” which we refer to here as the stigma complex, runs the risk of neither understanding nor avoiding unintended consequences of change efforts. Thus, complex systems such as FINIS call for transdisciplinary and translational collaboration.

The FINIS model in Figure 2 starts with Goffman’s notion that understanding stigma requires a language of social relationships. Yet it acknowledges that individuals do not come to social interaction devoid of psychological influences. This period of research pushes this realization further. Although FINIS acknowledges the importance of structural contexts, including organizations, media, and larger cultures, two European studies during this period provided strong empirical evidence of the link between public stigma and self-stigma (Evans-Lacko et al. 2011) and between public stigma and individual predisposition to help-seeking (Mojtabai 2010). Other research suggests the importance of potential neurological or genetic influences (see Kim & Sasaki 2014, Krendl et al. 2006). New research finds psychological inhibitory processes (Richman & Lattanner 2014), rejection sensitivity (Pachankis et al. 2014), and anxiety (Haslam 2006) associated with stigma.

Figure 2.

Framework Integrating Normative Influence on Stigma (FINIS). Adapted and reprinted with permission from Pescosolido et al. 2008b.

FINIS emphasizes the critical tension lying at the interface of community and individual actors (Pescosolido 1992). On the left-hand side of the FINIS model, social characteristics and illness characteristics combine to shape the evaluation of the person’s behavior as well as the probability that a stranger can easily identify a person with mental illness. The greater the extent to which the stigmatized person holds devalued statuses, the greater the likelihood that the potential stigmatizer will mark the problem as serious, label it as a mental illness, and endorse stigmatizing responses. To the extent that there is greater social differentiation between the target and the receiver (e.g., race/ethnicity differences, age differences), the more likely negative responses will be reported. Yet we lack a clear understanding of what those associations might be, as research during this period found sociodemographic characteristics to be (a) relatively impotent in their association with some forms of stigma (e.g., Livingston & Boyd 2010, Martin et al. 2007, Pescosolido 2013), (b) missing considerations of heterogeneity with traditional social categories (e.g., nativity among African American groups, Henning-Smith et al. 2013), or (c) lacking a consideration of the co-occurrence of group membership and structural disadvantage (Yang et al. 2014). Finally, controlling for the nature of the behavior or the assessment of a mark, attaching the label of mental illness to a vignette describing a person has an independent negative effect on social rejection (Martin et al. 2007).

The right-hand side of the FINIS model posits that stigma is embedded in a larger cultural context that shapes the extent to which stereotyping exists; the nature of social cleavages that define “others;” and the way that different groups accept, reject, or modify dominant cultural beliefs. All historical works, including Hinshaw (2006), note that stigma appears in all times and all places for which there is evidence. Although there are claims that stigma has dissipated (Pescosolido 2013), there is little hard evidence for HIV/AIDS or any other “condition.” In fact, there is evidence of no change in the public stigma of specific mental illness conditions and evidence of an increase in negative responses to alcohol dependence (Pescosolido et al. 2010). The evidence for other stigmatized statuses, however, is more encouraging (see Loftus 2001 on homosexuality, see Marsden 2012 on general trends in the US General Social Survey since 1972). However, some researchers argue that even in these more encouraging cases, the nature of stigma has been transformed, becoming more subtle but still evident nonetheless (e.g., see Rabinowitz et al. 2009 on symbolic racism). Changes in societal metaphors for qualifying for state benefits alter the nature of the mark, influence responses of self and others, but fail to reduce prejudice (Haslam 2006). Even state policies designed to protect those who are stigmatized may unwittingly put stigmatized individuals at greater risk. For example, Kozubal et al. (2013) found that HIPPA requirements prohibited 75% of hospitals from releasing in-patient psychiatric records to nonpsychiatrists treating those with mental illness, which the authors saw as resulting from stigma.

Media images, which reify or counter popular stereotypes, and community-based social networks, which function as a mechanism to magnify or dilute larger cultural stereotypes, are also part of the stigma complex. During this period, research provided more direct evidence of continued, negative media portrayals and impact (Corrigan et al. 2005, Heuer et al. 2011, Stepanova & Strube 2012). Further, cross-national variation in media portrayals also reflected differences. In social democratic welfare states (i.e., Iceland, Germany), stories on mental illness, for example, were more likely to include themes of social inclusion and “stigma,” whereas in a liberal welfare state (i.e., the United States), stories were more likely to make reference to danger, criminality, and the need for social segregation (Olafsdottir 2007).

The notion of contact with persons with mental illness has long been thought to be a potential source of change and a basic force in human lives. In fact, many earlier individual-level interventions focused on contact (Couture & Penn 2003, Estroff et al. 2004). However, during this period, Perry (2011) documented the irony that being formally labeled with a mental illness (i.e., diagnosis) initiated greater social support from the core network while producing greater rejection and discrimination by acquaintances and strangers (see also Lindsey et al. 2010 on African American families with boys diagnosed with depression).

At the organizational and institutional levels, a variety of advocacy groups express continual concern about treatment, with self-labeled “psychiatric survivors” maintaining that “official” psychiatry and its normative approach do more harm than good or, at minimum, do not help (Cresswell 2005). Others have been concerned that climate and culture of treatment settings often have unintended stigmatized effects, including the absence of hopeful messages from providers (Kelly 2006, Pescosolido 2006). Corrigan (2007) suggests that the very assignment of a diagnosis may unintentionally trigger stereotypes, including the notion that people with mental illness cannot recover. Although institutionalized stigma (Corrigan & Kleinlein 2007) is not limited to the treatment system, organizations themselves can be stigmatized (almost as a courtesy stigma or as the result of a scandal, failure, etc.). As Devers et al. (2009, p. 157) contend, an organization can be labeled in a way that “evokes a collective stakeholder group-specific perception” that it “possesses a fundamental, deep-seated flaw that deindividuates and discredits the organization.”

CONCLUSION: IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND SOCIAL CHANGE

As Livingston & Boyd (2010, p. 2,150) point out, “Conceptual clarity regarding ‘stigma’ is lagging behind the burgeoning body of research regarding its effects.” In the spirit of the irony of transdisciplinarity, recent research on stigma has seen those in health-related fields look to more traditional race-related frames of prejudice/discrimination for clarity, and those in the economics look toward stigma as a new way to understand economic discrimination (Loury 2003, Phelan et al. 2008). While this cross-fertilization has enhanced the richness of stigma research, it has also increased the haze of concepts and meanings and has called for greater theoretical clarity. By separating, defining, and providing examples of concepts, characteristics, premises, and variants, our aim was to offer a lexicon for unraveling who and what is being studied. We also proposed a stigma complex, a system of interrelated, heterogeneous parts that bring together insights across disciplines to provide a more realistic, albeit complicated, sense of the challenge facing the next generation of stigma research.

Stigma research in the beginning of a period of resurgence (from the mid-1990s onward) did away with speculation that stigma had been eradicated in many areas. It also revealed a surprising consistency in population levels and correlates in some areas (e.g., mental illness stigma in Western nations, Pescosolido 2013). Importantly, research since 2000 has continued to confront and shatter many other long-held expectations about stigma and the levers of stigma reduction. Most central among these are the link between education and stigma reduction (Pescosolido et al. 2010) and, particularly, the idea that the societal emphasis on genetic causation, if embraced by the public, would reduce prejudice (Phelan 2005). One clear conclusion from research over the past 14 years is that focusing on improving knowledge has limited value. Thus, it is no surprise that more and more policy makers in the medical and public health fields have suggested social inclusion as a potential direction of change (e.g., Carter et al. 2013).

As Goffman (1963) reminded us early on, stigma is fundamentally a social phenomenon rooted in social relationships and shaped by the culture and structure of society. As such, the solution to understanding and changing must similarly be embedded in social relationships and changing the structures that shape social relationships. Yet the research in this area remains at an early stage and primitive in nature. As Estroff et al. (2004) note, antistigma efforts are longstanding and widespread but little research has documented the range, impact, or locale of effectiveness (see Stuart et al. 2012 for a review of efforts, effects, and new direction for change). Even as researchers and policymakers note that “it may be unrealistic to think that we can eliminate stigma altogether” (Brown et al. 2001, p. 1), it can certainly be reduced and it is not likely to decrease on its own (Schnittker 2008).

Although research since 2001 has continued to delineate the full complement of the parts of the stigma complex, we know little about how these interrelated units work together. FINIS attempted to organize the parts of the system; it was less successful in depicting interactions among system parts. Yet research from this period has provided directions to do so. Aside from the direct links between macro and micro stigma that were revealed in the European studies described above (Evans-Lacko et al. 2011, Mojtabai 2010), other studies have suggested additional novel intersections. For example, Vogel et al. (2007) document that self-stigma mediates the impact of perceived stigma on individuals’ willingness to seek counseling. Further, as Wailoo (2006, p. 553) has pointed out, stigmas associated with group identity have accentuated and have been accentuated by disease-associated “hidden invisible traits” (Haitians and HIV/AIDS, African American men and schizophrenia, Asians and SARS, Hung 2004; see also layered stigmas, Reidpath & Chan 2005). Finally, the feedback loops, cycles, circles, and circuits that work in the stigma complex are important but understudied. For example, the general concern in medical sociology of how social status “gets under the skin” suggests that stigma is also subject to biological embedding, which according to Hertzman & Boyce (2010, p. 333) degrades well-being in “nonlinear and nonspecific ways” (see also B.A. Pescosolido, S. Olafsdottir, O. Sporns, B.L. Perry, E. Meslin, et al., unpublished manuscript, on the trio of social embeddedness, biological embeddedness, and biological embedding).

Some of the calls for the next generation of research remain the same. More longitudinal research would provide a better sense of dynamics and levers (Link et al. 2008, Livingston & Boyd 2010 as a recent exception). More qualitative research may get at “subtleties, complexities and contextual nature” of stigma (MacLeod & Austin 2003, p. 117) that cannot be captured through direct questions (see also Link et al. 2004, MacLeod & Austin 2003). Social science, ethical, or philosophical considerations of the underlying moral processes that create stigmatized statuses are also in order (Kleinman & Hall-Clifford 2009). As we have argued before, individuals are more willing to express stigma than to act on it, setting monitoring of public stigma as the litmus test for marking challenges and crafting public health interventions (Olafsdottir & Pescosolido 2011, Pescosolido et al. 2008c). Yet other classic social science research suggests that longer-term efforts that are broad-based and prohibit discrimination, rather than those that change hearts and minds in the short run, may be a poor fit with the small-scale, individual-level efforts that align with the randomized, clinical trial model most commonly thought to be the gold standard in many areas of science. Further, consideration of the social resistance framework (Factor et al. 2011, 2013) suggests that resistance that produces unhealthy behavior must directly address and channel issues of frustration toward empowerment. Thus, to understand the stigma complex, we must consider novel designs, transdisciplinary teams, and longer frames for research.

Acknowledgments

This article would not be possible without the support of a multidisciplinary group of researchers who have developed a dialogue of theoretical and methodological discussion increasingly engaged with consumers, policy makers, and the designers of programmatic efforts to reduce the pain and suffering of those that confront stigma in their daily lives. This community has been facilitated by the support of the Indiana University College of Arts and Sciences; the Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research; the international conference “Together Against Stigma,” led by Heather Stuart; the Carter Center’s Mental Health Program, headed by Tom Bornemann and Rebecca Palpant Shimkets; and Bring Change 2 Mind, founded by Glenn Close and directed by Pamela Harrington. Although other key individuals in this dialogue, including colleagues at Indiana University-Bloomington, graduate students who have gone on to their own distinguished careers, coauthors, and key consultants, are too numerous to name, we give particular thanks to Alex Capshew and Mary Hannah, who are always there. We would also like to acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (#R01 TW006374-01, #5 R01MH074985) during those periods when issues of stigma were on their agenda.

Footnotes

According to Google Scholar, 169,000 articles and books published between 2001 and 2010 included the word “stigma” in the title. Another 41,500 articles and books were published between 2011 and 2015.

We do not include the concept of “felt” stigma (Scambler 2009) because it has been used to include both anticipated and received stigma.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abadía-Barrero CE, Castro A. Experiences of stigma and access to HAART in children and adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006;62:1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Kaiser DM. The experience of stigma among Black mental health consumers. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:874–893. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, Elam G, Gerver S, Solarin I. HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: accounts of HIV-positive Caribbean people in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;67:790–798. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Causal beliefs and attitudes to people with schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;186:331–334. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Schulze B, Dietrich S. Courtesy stigma: a focus group study of relatives of schizophrenia patients. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0680-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argo JJ, Main KJ. Stigma by association in coupon redemption: looking cheap because of others. J. Consum. Res. 2008;35:559–572. [Google Scholar]

- Asbring P, Narvanen AL. Women’s experiences of stigma in relation to chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2002;12:148–160. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin JK, Shafer JB. Epilepsy familiarity, knowledge, and perceptions of stigma: report from a survey of adolescents in the general population. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:368–375. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay P, Save D, Fidanoglu O. Does stigma concerning mental disorders differ through medical education? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006;41:63–67. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0994-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN. Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2007;16:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, Goldman HH. Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015;65(10):1269–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascompte J. Disentangling the web of life. Science. 2009;325:416–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1170749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer R, Stuber J. Tobacco control, stigma, and public health: rethinking the relations. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96:47–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A. “Less than the average citizen”: stigma, role transition and the civic reintegration of convicted felons. In: Maruna SM, Immarigeon R, editors. After Crime and Punishment: Pathways to Offender Reintegration. Portland, OR: Willan; 2004. pp. 261–293. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Agnew-Blais J, Gilman SE. Past horrors, present struggles: the role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010;70:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo L, Kluegel JR, Smith RA. Laissez faire racism: the crystallization of a “kinder, gentler” anti-Black ideology. In: Tuch SA, Martin JK, editors. Racial Attitudes in the 1990s: Continuity and Change. Greenwood, CT: Praeger; 1997. pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogardus ES. Social Distance. Yellow Springs, OH: Antioch Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd Ritsher J, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G GAMIAN-Europe Study Group. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr. Res. 2010;122:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Trujillo L, Macintyre K. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Educ. Prev. 2003;15(1):49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. Naming and framing: the social construction of diagnosis and illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995;1995(Spec. No.):34–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J. Dispelling a myth: Developing world poverty, inequality, violence and social fragmentation are not good for outcome in schizophrenia. Afr. J. Psychiatry. 2009;12:200–205. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v12i3.48494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne A, Carr D. Caught in the cultural lag: the stigma of singlehood. Psychol. Inq. 2005;16:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S. Hitting the bricks. Observer. 2005;18:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Satcher D, Coelho T. Addressing stigma through social inclusion. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:773. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Farmer P. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95:53–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.028563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-K, Hayes RD, Perera G, Broadbent MTM, Fernandes AC, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e19590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]