Abstract

Objective

Detection of focal brain tau deposition during life could greatly facilitate accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), staging and monitoring of disease progression, and development of disease modifying therapies.

Methods

We acquired tau positron emission tomography (PET) using 18F T807 (AV1451), and amyloid-β PET using 11C Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) in older clinically normal individuals, and symptomatic patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild AD dementia.

Results

We found abnormally high cortical 18F T807 binding in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD dementia compared to clinically normal controls. Consistent with the neuropathology literature, the presence of elevated neocortical 18F T807 binding particularly in the inferior temporal gyrus was associated with clinical impairment. The association of cognitive impairment was stronger with inferior temporal 18F T807 than with mean cortical 11C PIB. Regional 18F T807 was correlated with mean cortical 11C PiB among both impaired and control subjects.

Interpretation

These findings suggest that 18F T807 PET could have value as a biomarker that reflects both the progression of AD tauopathy and the emergence of clinical impairment.

MeSH: Tau, PET, amyloid, PiB

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is neuropathologically defined and staged by the presence and distribution of two proteinaceous deposits, extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) and intracellular tau.1, 2 Until recently these lesions could not be detected during life, and their presence and distribution could only be evaluated at autopsy. A breakthrough reported in 2004 enabled researchers using positron emission tomography (PET) with 11C Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) to detect Aβ deposits in living humans, and Aβ PET is now widely used in clinical trials of anti-Aβ therapies to identify individuals with AD pathology.3 The detection of Aβ by PET tracers with very high molecular specificity has been confirmed by histopathologic correlation studies.4, 5 More recently, Kolb and colleagues tested a family of compounds based on binding to tau-laden postmortem AD brain slices.6 Candidate ligands were compared with autoradiography to evaluate human frontal cortex sections from brains with a range of tau and Aβ pathology. 18F T807 did not bind Aβ, and its affinity, metabolic stability, and low nonspecific binding in white matter or normal gray matter were very favorable.6 In an initial report, two patients with AD and one with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), had elevated 18F T807 binding compared to three normal controls.7 These findings, along with reports of additional tau PET radiopharmaceutical developments, including THK523, THK5105, THK5117, PBB3, and 18F T808 (reviewed in reference 8), led us to test whether 18F T807 binding would be elevated in neocortical areas in impaired subjects compared to normal controls, whether the binding would be related to cognitive status, and whether 18F T807 would correlate with 11C PiB measures of Aβ deposition.7–11 We also tested the hypothesis that extensive T807 retention would occur only in the setting of substantial cortical amyloid deposition, i.e., whether cortical 18F T807 would be most common in subjects with elevated 11C PiB measures of Aβ deposition in cortex.7–11

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Harvard Aging Brain Study, a longitudinal study on aging and Alzheimer’s disease, from Memory Disorders Clinics at the Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals, and from the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. All participants provided informed consent and were studied under protocols approved by the Partners Human Research Committee. All subjects underwent at least one comprehensive medical and neurological evaluation and none had medical or neurological disorders that might contribute to cognitive dysfunction, history of alcoholism, drug abuse, or head trauma, or a family history of autosomal dominant AD. None were clinically depressed at the time of study (Geriatric Depression Scale <11) or had other psychiatric illnesses.12 Each participant underwent a cognitive evaluation that included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale, and the Logical Memory delayed recall (LM).13–15

Participants were either clinically normal (CN) or cognitively impaired (Table 1). CN subjects (N=56) had a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) global score of 0, MMSE > 25, and performance within 1.5 SD on age-and-education–adjusted norms on cognitive testing at the time of recruitment into the Harvard Aging Brain Study.15–18 Cognitively impaired participants fulfilled NIA research criteria for either mild cognitive impairment (MCI; N = 13; global CDR = 0.5) or AD dementia (N = 6; global CDR = 1).19, 20 Patients with atypical clinical syndromes, such as posterior cortical atrophy, semantic dementia, or Dementia with Lewy Bodies, were not included. Because of the symptomatic continuum between MCI and mild AD dementia, and the smaller numbers of participants in impaired groups compared to the CN group, the majority of analyses were performed with a combined MCI/AD impaired group.

Table 1.

Demographics

| All | CN | MCI | AD | MCI/AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%F) | 75 (43) | 56 (48) | 13 (23) | 6 (33) | 19 (26) |

| Age, yr | §73±8 (49–90) | 75±6 (65–89) | 71±9 (59–90) | 63±12 (49–78) | 69±10* (49–90) |

| Education, yr | 16±3 (12–20) | 16±3 (12–20) | 17±3 (12–20) | 14±3 (12–18) | 16±3 (12–20) |

| MMSE | 28±4 (11–30) | 29±1 (26–30) | 26±2* (22–30) | 17±5* (11–23) | 24±5* (11–30) |

| CDR-SB | 1±2 (0–11) | 0±0 (0–1.5) | 2±1.5* (0–5.5) | 6±4* (2.5–11) | 3±3* (0–11) |

| 11C PiB DVR | 1.32± .3 (1.05–2) | 1.24± .2 (1.05–1.81) | 1.48± .3* (1.07–1.92) | 1.76± .21* (1.45–2) | 1.57± .3* (1.07–2) |

Values are mean ± standard deviation (range)

CN= Cognitively Normal

MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment

AD = Alzheimer's Disease dementia

MMSE= Mini Mental State Exam

CDR-SB= Clinical Dementia Rating, sum of boxes

DVR= distribution volume ratio

differs from CN, p < 0.05.

Image Acquisition and Processing

PET: 18F T807 (AV1451) was prepared at MGH with a radiochemical yield of 14±3% and specific activity of 216±60 GBq/µmol at the end of synthesis (60min), and validated for human use.21 11C Pittsburgh Compound B was prepared and PET data were acquired as described previously.16 All PET data were acquired using a Siemens/CTI (Knoxville, TN) ECAT HR+ scanner (3D mode; 63 image planes; 15.2cm axial field of view; 5.6mm transaxial resolution and 2.4mm slice interval. 11C PiB PET was acquired with a 8.5 to 15 mCi bolus injection followed immediately by a 60-minute dynamic acquisition in 69 frames (12×15 seconds, 57×60 seconds). 18F T807 was acquired from 80–100 minutes after a 9.0 to 11.0 mCi bolus injection in 4 × 5-minute frames. PET data were reconstructed and attenuation corrected, and each frame was evaluated to verify adequate count statistics and absence of head motion. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) lag time between 18F T807 and MMSE and CDR ratings was 4.9 ± 3.5 months, and between 18F T807 and 11C PiB PET imaging, 3.5 ± 2.6 months.

MRI was performed on a 3T Tim Trio (Siemens) and included a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) processed with Freesurfer (FS) as described previously to identify grey-white and pial surfaces to permit ROI parcellation as follows: cerebellar grey, hippocampus, and the following Braak Stage related cortices: entorhinal (ER), parahippocampal (PH), inferior temporal (IT), fusiform (FF), posterior cingulate (PC), as described previously.16, 22–25

To evaluate the anatomy of cortical T807 binding, each individual PET data set was rigidly co-registered to the subject’s MPRAGE data using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Function Imaging Laboratory, London). The cortical ribbon and subcortical ROIs defined by MR as described above were transformed into the PET native space; PET data were sampled within each right-left ROI pair. SUVR values were represented graphically on vertices at the pial surface. PET data were not partial volume corrected.

18F T807 specific binding was expressed in FS ROIs as the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) to cerebellum, similar to a previous report, using the FS cerebellar grey ROI as reference. For voxel-wise analyses, each subject’s MPRAGE was registered to the template MR in SPM8 (SPM), and the spatially transformed SUVR PET data was smoothed with a 8 mm Gaussian kernel to account for individual anatomic differences.7

11C PiB PET data were expressed as the distribution volume ratio (DVR) with cerebellar grey as reference tissue; regional time-activity curves (TAC) were used to compute regional DVRs for each ROI using the Logan graphical method applied to data from 40 to 60 minutes after injection.16, 26 11C PiB retention was assessed using a large cortical ROI aggregate that included frontal, lateral temporal and retrosplenial cortices (FLR) as described previously.17, 27

Statistical analyses

18F T807 SUVR in CN and MCI/AD were compared both voxel-wise and within FS-defined ROI. PET ROI measures in each group were correlated with age using Spearman’s rho, with Bonferroni adjusted alpha levels of .0083 (.05/6 ROIs). The associations of APOEe4 carrier status with PET ROI were assessed with Wilcoxen tests. Effect sizes for clinical group classification in individual ROIs were evaluated with Mann-Whitney U-tests and expressed as Cohen’s d. 11C PIB FLR was used as a continuous measure of Aβ and also as a dichotomous measure, with high Aβ defined as FLR DVR>1.2.18 One MCI subject was classified as high Aβ on the basis of low cerebrospinal fluid (Aβ 1–42 = 195 pg/ml; ADmark, Athena Diagnostics) and did not have PiB data available. Correlations between mean cortical PiB and inferior temporal 18F T807 measures as well as relationships with age, MMSE, CDR sum of boxes (CDR-SB), and Logical Memory, were evaluated with Spearman’s rho. MMSE and CDR-SB were also evaluated as ordinal data using cumulative logit models and estimating a separate log odds for each cut-point of MMSE or CDR-SB.

Results

1. Demographic and biomarker measures

Table 1 gives the participant characteristics. The MCI/AD group in comparison to the CN group was younger (p<0.05), more impaired on the MMSE and CDR (p<0.05), and had higher 11C PiB DVR (p<0.05).

In the MCI/AD group, greater age was associated with higher 18F T807 binding in PH (rho=−0.61, p<0.006), IT (rho=−0.70, p<0.001), FF (rho=−0.59, p<0.008), and PC (rho=−0.81, p<0.001). In the CN group: 1) greater age was associated with higher PiB DVR (rho=0.38, p<0.004) and higher 18F T807 SUVR binding in IT (rho=0.46, p<0.001); 2) APOEe4 carrier status (median ages: 17 e4 carriers, 72 y; 39 non-carriers, 74 y) was associated with PiB DVR (p<0.009), but not with 18F T807 binding in any ROI at a 0.05 level of significance. Neither gender nor years of education was associated with any PET measure in either group.

2. 18F T807 cortical binding correspondence with expectations based on neuropathological studies

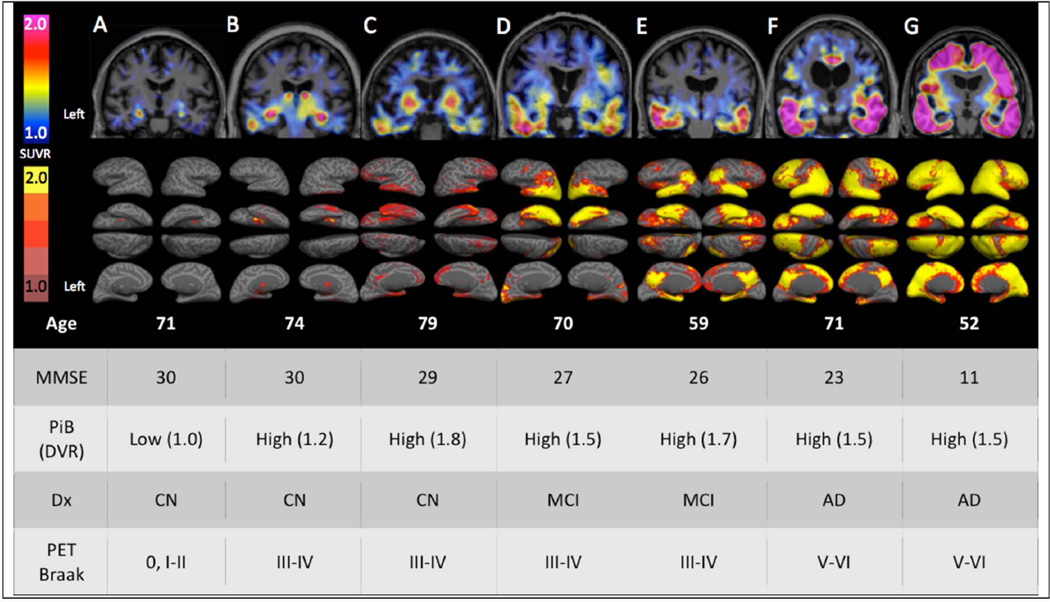

While direct image to tissue correspondence was not assessed in this in vivo study, the patterns of cortical 18F T807 binding visualized with surface-projected SUVR thresholds were anatomically consistent with the ordinal Braak staging scheme (0, I/II, III/IV, and V/VI) as follows.22, 28–30 Corresponding to Braak Stages 0, I or II, most CN subjects had low overall binding or only medial temporal lobe binding (Fig 1A–C), whereas more extensive neocortical binding in impaired subjects was always associated with much higher levels of temporal binding (Fig 1, D–G). Highest levels of neocortical binding, consistent with Braak Stages V/VI, were associated with selective sparing of primary cortices (Fig 1F–G). These anatomic patterns were confirmed quantitatively by the voxel-wise and ROI measures described below, and their commonalities with Braak Stages are summarized in Discussion.

Figure 1.

Cortical patterns of 18F T807 binding. Coronal 18F T807 PET images (top row) and whole-brain surface renderings of SUVR (second row) from 3 normal (CN) and 4 impaired (2 MCI and 2 AD dementia) participants. Top row A. A 71 year-old CN with low Aβ by PiB PET (DVR=1.0) had low, non-specific 18F T807 binding in cortex, consistent with a Braak Stage less than III/IV. B. A 74 year-old CN with high Aβ (DVR=1.2) with 18F T807 binding in inferior temporal cortex, left>right, consistent with Braak Stage III/IV. C. A 79 year-old CN, high Aβ (DVR=1.8) had binding in inferior temporal neocortex, consistent with Braak Stage of III/IV. B and C show focally intense subcortical uptake that is likely due to off-target binding (see Discussion). D–G. Cognitively impaired participants all with high Aβ and with successively greater levels of cortical 18F T807 binding successively involving temporal, parietal, frontal and occipital cortices. Second row: 18F T807 SUVR calculated at vertices (see Methods) indicating the extent of cortical binding, with left hemisphere views (lateral, inferior, superior, medial) at left. The 52 year-old AD dementia patient (G) showed confluent 18F T807 binding that is nearly pancortical, sparing only portions of primary cortex and consistent with Braak Stage V/VI.

MMSE= mini-mental state exam

PiB= Pittsburgh Compound B

DVR= distribution volume ratio, mean cortical

SUVR= standardized uptake value, cerebellar reference

Dx= classification (CN, clinically normal; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD mild AD dementia)

PET Braak= Estimate of Braak Stages is based on the anatomic pattern of T807 binding assessed visually and quantitatively in regions and full volume data.

3. Regional 18F T807 binding in cognitively impaired compared to CN subject groups

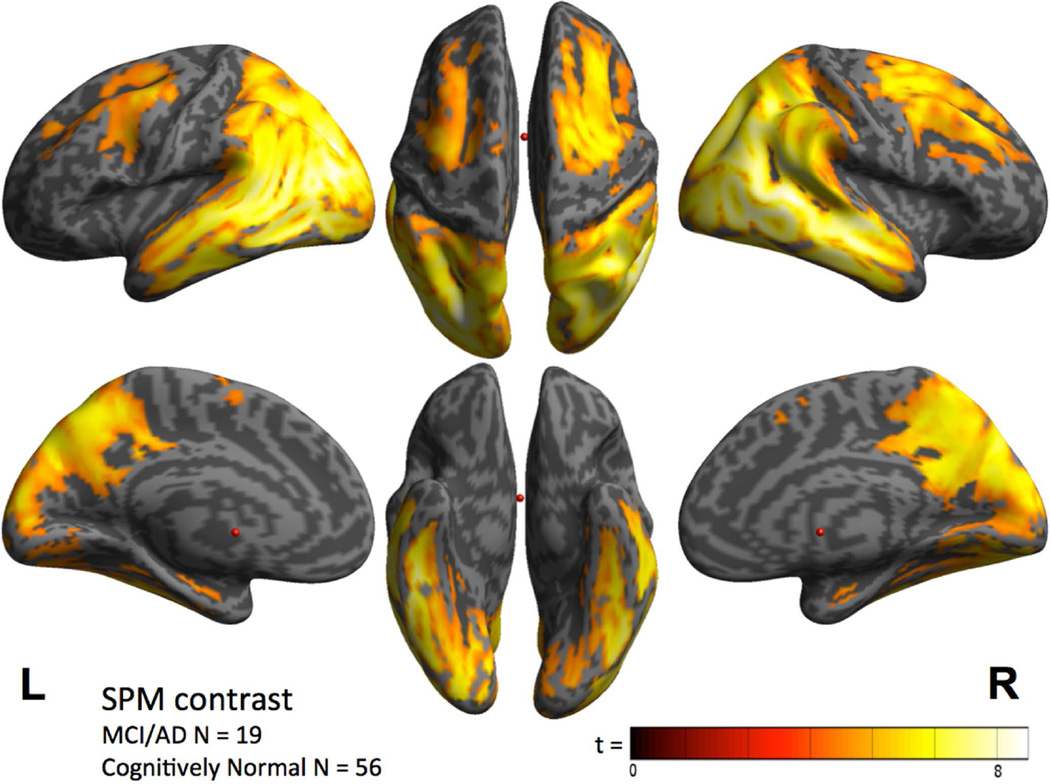

Contrast maps of voxel-wise analyses revealed that group mean 18F T807 cortical SUVR was elevated in the MCI/AD group in widespread neocortical regions, most prominently in inferior and lateral temporo-parietal, parieto-occipical and posterior cingulate/precuneus (Fig 2). Significant but lower magnitude elevations were seen in frontal regions, while the least affected areas included the primary cortices, including calcarine, sensori-motor, and auditory (Fig 2). These data were consistent with the individual threshold-based anatomic assessments exemplified in Figure 1, in that statistical significance was either not reached or was lower in medial and inferior temporal cortex (Fig 2) because many individuals in the CN group had modestly elevated SUVR in medial and inferior temporal regions, as confirmed with ROI analyses described below.

Figure 2.

Cortical distribution of T807 binding, contrast between the combined MCI/AD group (N=19) and the CN group (N=56; threshold p< 10^−5).

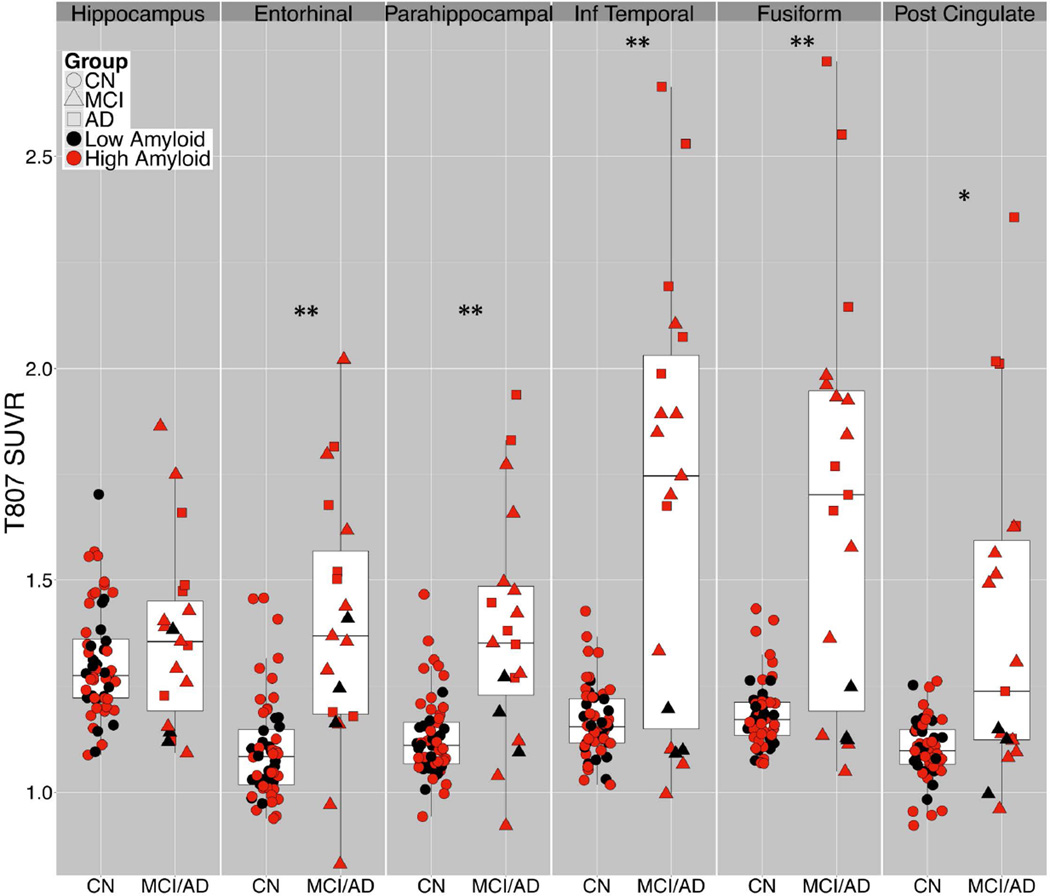

With ROI based analyses (Fig 3), group comparison results fell into 3 categories. 1) Hippocampal 18F T807 ROI binding was not significantly elevated in MCI/AD compared to CN, possibly due to off-target binding in adjacent structures (exemplified in Fig 1B); this potential confound is the topic of a separate investigation.31 2) In ER and PH, 18F T807 binding was significantly higher in MCI/AD than in CN, but with notable overlap between groups and a right-skewed distribution of CN subjects. 3) In IT and FF, group mean differences were greater than in ER and PH and the overall distribution appears bimodal: all CN subjects had SUVR < 1.5 and all AD had SUVR > 1.5. These differences were reflected in the effect sizes for AD versus CN, e.g., Cohen’s d = 7.63 for IT (Table 2). In the MCI group, 7 of 13 had IT and FF SUVR <1.5, i.e., within the range of CN, while the remaining 6 had SUVR >1.5, within the range of AD. Of the 7 MCI brains with IT T807 SUVR>1.7, the same 7 individuals also had the highest binding in ER and FF, and 6 of the 7 had the highest binding in PH. MCI subjects with 18F T807 SUVR>1.5 in IT and FF were significantly (U-tests) younger (63.8 ± 4.5 vs. 77.4 ± 7.6; p<0.01) and more impaired on MMSE (24.7 ± 2 vs. 28.1 ± 2; (p<0.01) and on CDR-SB (1.1 ± 0.6 vs. 3.0 ± 1.5; p<0.05) than those with SUVR<1.5. In addition, 11C PiB DVR was elevated (>1.2) in all subjects with IT and FF 18F T807 SUVR >1.25.

Figure 3.

Regional T807 binding according to diagnostic group. T807 standardized uptake value radio (SUVR) in regions-of-interest (ROI) by diagnostic group (CN, circles; MCI, triangles; AD, squares) and amyloid status (high Aβ, red, = PiB DVR 1.2 or greater), showing range, mean, interquartile range. t-test: *p<0.01, **p<0.001

Table 2.

T807 binding in ROIs, comparing MCI, AD, and combined MCI/AD groups with CN subjects.

| ROI | CN N=56 |

MCI N=13 |

MCI d |

AD N=6 |

AD d |

MCI/AD | MCI/AD d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PiB DVR | 1.24 (0.18) | 1.48 (0.30) | 1.12* | 1.76 (0.21) | 2.72*** | 1.57 (0.30) | 1.50*** |

| Inferior Temporal | 1.17 (0.08) | 1.47 (0.40) | 1.60 | 2.19 (0.36) | 7.63*** | 1.69 (0.51) | 1.97** |

| Fusiform | 1.18 (0.08) | 1.49 (0.39) | 1.70 | 2.09 (0.46) | 5.87*** | 1.68 (0.49) | 1.94*** |

| Posterior Cingulate | 1.10 (0.07) | 1.24 (0.23) | 1.22* | 1.73 (0.48) | 3.98*** | 1.40 (0.39) | 1.43*** |

| Parahippocampal | 1.13 (0.09) | 1.31 (0.25) | 1.37* | 1.54 (0.28) | 3.32*** | 1.38 (0.27) | 1.61*** |

| Entorhinal | 1.10 (0.12) | 1.36 (0.32) | 1.47** | 1.48 (0.26) | 2.76*** | 1.40 (0.26) | 1.62*** |

| Hippocampus | 1.31 (0.13) | 1.36 (0.23) | 0.32 | 1.39 (0.19) | 0.58 | 1.37 (0.22) | 0.38 |

d = Cohen’s d, effect size of group vs. CN

= p < 10−3,

= p < 0.01,

= p < 0.05 as defined by Mann-Whitney U p-value of group vs. CN. Bonferroni adjusted p-value threshold for 6 brain regions is 0.008. We did not correct for analyses of different subgroups of subjects within regions due to the high correlation among these subgroups and over-conservatism of Bonferroni in that setting.

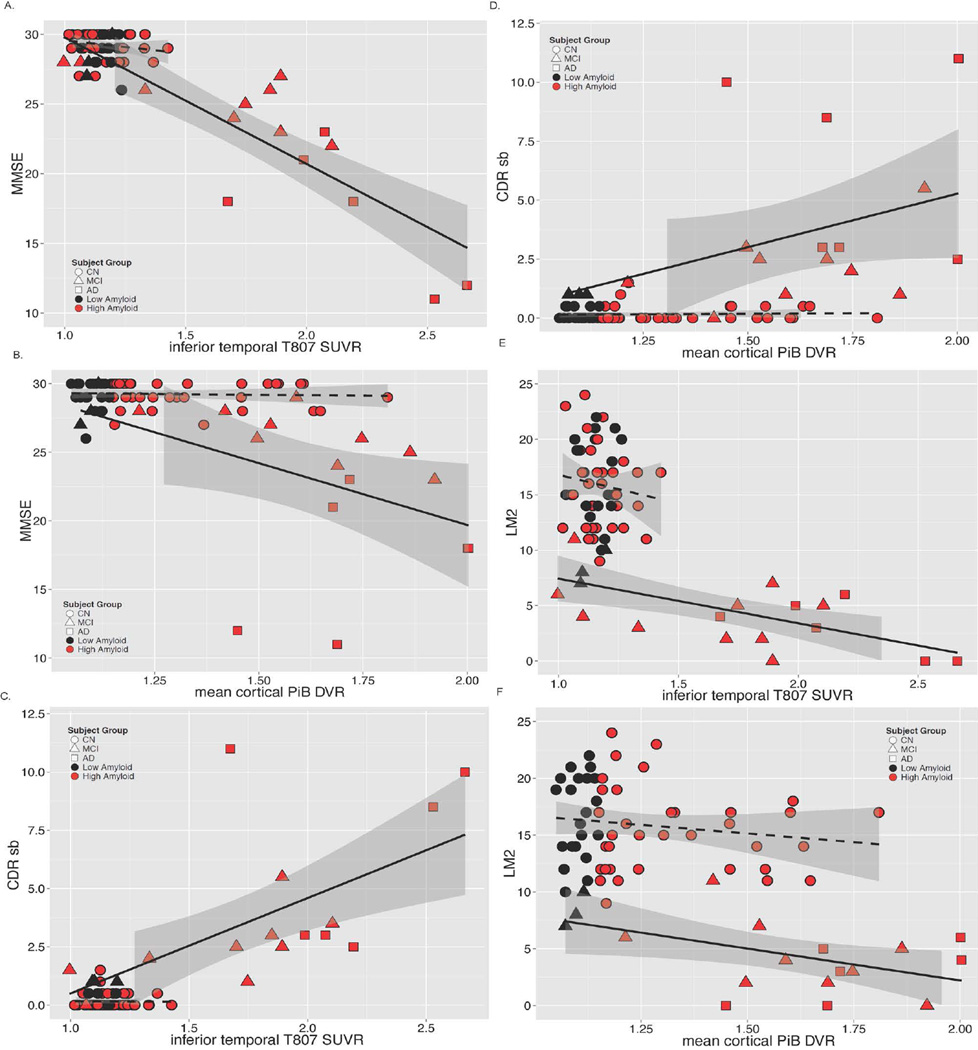

4. 18F T807 and PiB binding in relation to clinical status and to each other

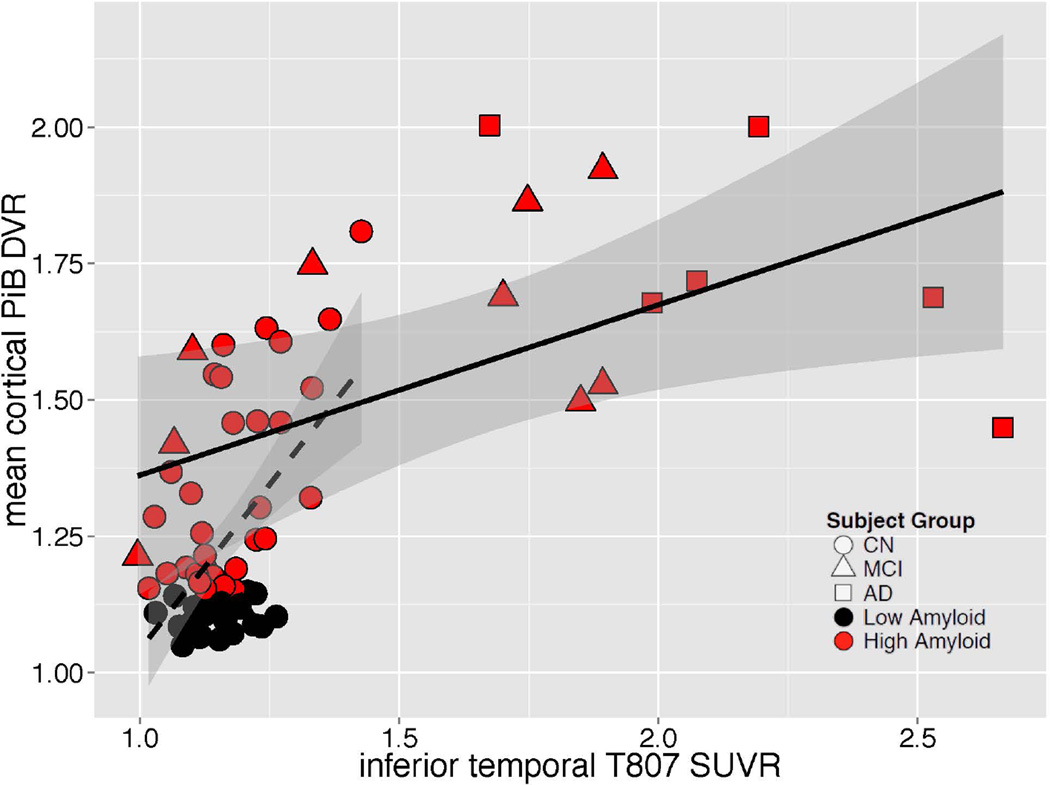

In the MCI/AD group, greater inferior temporal 18F T807 SUVR was related to greater impairment on MMSE, CDR-SB and LM (Fig 4); similar but weaker associations (lower Rho values) were observed between greater PiB DVR and greater impairment on MMSE, CDR-SB and LM. Inferior temporal 18F T807 binding was associated with higher mean cortical PiB retention in both the full sample and in separate analyses of CN and MCI/AD (Fig 5). Across the full sample, inferior temporal 18F T807 SUVR was >1.3 only in those individuals with high PiB DVR (Fig 5).

Figure 4.

A – F. Correlations of Tau pathology measured with 18F T807 and Aβ pathology measured with 11C PiB with Mini-Mental State Examination, CDR Sum of Boxes, and Logical Memory 2. Clinically normal subjects are represented with circles, MCI with triangles, and AD with squares; red indicates high Aβ (PiB DVR >1.2) and black low Aβ (PiB DVR ≤1.2). Spearman correlations (rho) are given below for each PET measure versus MMSE, CDR SB, or LM.

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

p | Cumulative logit, log OR |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | −0.20 | 0.14 | 4.20 | 0.18 |

| MCI/AD | 19 | −0.83 | < 10−4 | 6.89 | < 10−4 |

| All | 75 | −0.46 | < 10−4 | 7.28 | < 10−4 |

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

p | Cumulative logit, log OR |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | −0.05 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.59 |

| MCI/AD | 18 | −0.63 | 0.005 | 5.38 | 0.003 |

| All | 74 | −0.40 | < 10−3− | 4.59 | < 10−4 |

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

p | Cumulative logit, log OR |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | 0.02 | 0.89 | −0.72 | 0.84 |

| MCI/AD | 19 | 0.75 | 0.0002 | −4.93 | 0.0002 |

| All | 75 | 0.42 | 0.0002 | −6.05 | < 10−4 |

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

P | Cumulative logit, log OR |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | 0.04 | 0.77 | −0.97 | 0.54 |

| MCI/AD | 18 | 0.52 | 0.03 | −3.85 | 0.02 |

| All | 74 | 0.39 | 0.0005 | −4.33 | < 10−4 |

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | −0.10 | 0.45 |

| MCI/AD | 19 | −0.58 | 0.01 |

| All | 75 | −0.39 | 0.0006 |

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | −0.12 | 0.36 |

| MCI/AD | 18 | −0.50 | 0.04 |

| All | 74 | −0.42 | 0.0002 |

Figure 5.

| Group | N | Spearman ρ |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 56 | 0.32 | 0.02 |

| MCI/AD | 18 | 0.51 | 0.03 |

| All | 74 | 0.53 | <10−4 |

Discussion

We evaluated 18F T807, a PET radiopharmaceutical selective for tau pathology by comparing clinically normal individuals to patients classified clinically as mild cognitive impairment or mild AD dementia. Large differences in 18F T807 neocortical binding were detected between clinically defined groups; for example, Cohen’s d was 7.6 for AD dementia vs. CN in inferior temporal lobe. Furthermore, 18F T807 levels were correlated with measures of cognitive and functional impairment both across the entire sample and within the impaired group. This initial experience suggests that tau PET measures may be useful as a molecular imaging biomarker distinguishing impaired from unimpaired individuals, tracking progression of disease, and assessing response to putative disease-modifying treatments. 18F T807 binding in the MCI/AD group was especially high in neocortical regions, including inferior temporal lobe, consistent with neuropathologic studies in which tau pathology at Braak Stages III/IV or higher has been associated with AD dementia.22, 23, 32

Binding of the 18F T807 ligand occurs specifically at sites of tauopathy, raising the possibility that when PET signal is sufficient to emerge from background, in vivo detection and anatomic staging of tau deposition is possible.6 It has long been hypothesized on the basis of autopsy material that tau deposition spreads beyond the entorhinal cortex in temporal proximity to cognitive impairment.2, 22–24, 32 Our data support this hypothesis because we found that greatly elevated 18F T807 binding in temporal neocortex (e.g., SUVR>1.5) was only observed in subjects with cognitive impairment. If these observations are verified in longitudinal samples where the time course can be examined, the development of tau pathological lesions in the temporal neocortex will be a risk factor detectable by PET for increased likelihood of emergence of the dementing phase of AD. This may well enable more accurate clinical diagnosis and be a useful outcome measure in clinical trials.

Across the full sample of subjects, several features of the pattern of 18F T807 binding were qualitatively consistent with expected anatomic patterns, while other features were not consistent. For example, as expected, successively higher binding was seen in infero-lateral temporal regions, and temporo-parietal to frontal regions.22 The somewhat stronger statistical signal seen in occipito-parietal compared to frontal neocortical regions (Fig 2) is consistent with neuropathologic observations.22,23 In addition, widespread binding consistent with later Braak stages spared primary cortices and was invariably accompanied by high levels of binding in the temporal lobe.

Two features were not consistent with expectations based on patho-anatomic studies. Contrary to Braak Staging predictions, we did not see a consistent pattern of successively greater 18F T807 in the hippocampus with more advanced disease. We postulate that this observation may be due in part to off-target binding adjacent to hippocampus; however PET detection of 18F T807 binding in hippocampus is particularly susceptible to artifact when atrophy is a factor, due to small volume and surrounding CSF.

Second, 18F T807 binding to an area near the substantia nigra is more likely to be off-target since limited neurofibrillary pathology occurs in this structure. The potential for off-target binding of 18F T807 or other ligands may be a limitation for their use in staging tau pathology. Ex vivo autoradiography may clarify this issue by identifying off-target 18F T807 binding, including sources of a suspected confound of signal spill-in from structures adjacent to the hippocampus (Fig 1).31 Post mortem correlative studies are clearly necessary, as they continue to be for Aβ PET, to identify biological substrates. However, preliminary experience with 18F T807 suggests that a PET-based staging of AD pathology could be established on the basis of cortical 18F T807 binding for tau, which could be useful either alone or in combination with measures of Aβ. Technical factors will require continued evaluation for potential clinical implementation of 18F T807 PET, including choice of window for imaging based on kinetic modeling, choice of reference region and image quantitation protocols.7

We observed a significant relationship between age and inferior temporal 18F T807 binding within the relatively restricted age range of our normal participants, consistent with large autopsy studies.2 Studies of 18F T807 PET in younger subjects will be required to test whether entorhinal cortex binding in older normal subjects exceeds that in younger subjects, as predicted by reports with Braak Staging, and whether this binding represents a tauopathy that, while primarily age-related, is accompanied by subtle but measurable levels of cognitive impairment.33, 34 It must be born in mind, however, that compared to the microscopy – based Braak staging scheme, tau PET staging of AD is inherently limited because of the lower resolution and sensitivity of PET. For example, current PET technology is not likely to detect or distinguish tau deposition in entorhinal cortex that separates Braak 0 from 1 or 2.

On the other hand, the subset of clinically normal older individuals with elevations in both temporal lobe 18F T807 binding and in mean cortical Aβ estimated with PiB or other Aβ ligands, may be at elevated risk for imminent clinical and cognitive decline. We observed a trend-level association in CN subjects between elevated 18F T807 and worse MMSE and further evaluation using more sensitive cognitive measures is warranted.

In the combined CN and MCI/AD sample, levels of neocortical tau deposition greater than SUVR >1.3 were only observed in individuals with elevated Aβ (PiB DVR>1.2). This finding is consistent with the idea that along the AD trajectory high levels of tau in neocortex are only seen in those with high Aβ burden, however more extensive evaluation in larger samples will be required to determine whether this is a robust finding. While longitudinal studies with serial 18F T807 imaging will be critical to understand the time course of tau spread, and to determine whether the pattern of anatomic spread is similar to the pattern of tau deposition described in autopsy studies, our findings thus far suggest that 18F T807 PET imaging may prove valuable in monitoring progression of AD related neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Aging (R01 AG046396, P01 AG036694, P50 AG00513421), Fidelity Biosciences, Harvard Neurodiscovery Center, and the Alzheimer’s Association.

KAJ has provided consulting services for Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, Roche, Piramal, GE Healthcare, Siemens, ISIS Pharma, AZTherapy, and Biogen, received support from a joint NIH-Lilly-sponsored clinical trial (A4 Study - U19AG10483), and received research support from National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Aging (R01 AG046396, P01 AG036694, P50 AG00513421, U19AG10483, U01AG024904-S1), Fidelity Biosciences, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Association. EM receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health. MA has provided consulting services for Takeda and Merck. BD has provided consulting services for Merck and Forum. TS reports a patent “Radiosynthesis of tau radio-pharmaceuticals” (2014) WO 2014194169 A1 20141204 issued. BH reports grants from NIH during the conduct of the study, grants and personal fees from Siemens, personal fees from Calico, ISIS Pharma, Lilly, Neurophage, Pfizer, Biogen, Genetech, Sanofi, Abbvie, personal fees and other from Novartis, grants from BMS, AZTherapy, Acumen, Prothena, Fidelity Biosciences, Spark, Intellect, outside the submitted work. NV reports a patent “Radiosynthesis of tau radio-pharmaceuticals” (2014) WO 2014194169 A1 20141204 issued. RAS has provided providing consulting services for Roche, Genentech, Biogen and Bracket, received support from a joint NIH-Lilly-sponsored clinical trial (A4 Study - U19AG10483), and research funding from the National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Aging (R01 AG046396, P01 AG036694, P50 AG00513421) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: KAJ contributed to conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revision of the report, and statistical analysis. RB contributed to drafting and revision of the report and to the statistical analysis. AS, JAB, JS, DR, EM, JC, RA, KP, GM, MA, BD, TG, BH, NV, RAS contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of the report. SM, LP, JA, KJ, MP, TS, DY contributed to drafting and revision of the report, and provided technical support.

Potential Conflict of Interests: AS, RB, JAB, JS, DR, EM, JC, RA, KP, GM, SM, LP, JA, KJ, MP, TS, DY, and TG have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(5):362–381. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-β plaques: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(8):669–678. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinne JO, Wong DF, Wolk DA, et al. [(18)F]Flutemetamol PET imaging and cortical biopsy histopathology for fibrillar amyloid β detection in living subjects with normal pressure hydrocephalus: pooled analysis of four studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(6):833–845. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia C-F, Arteaga J, Chen G, et al. [(18)F]T807, a novel tau positron emission tomography imaging agent for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(6):666–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien DT, Bahri S, Szardenings AK, et al. Early clinical PET imaging results with the novel PHF-tau radioligand [F-18]-T807. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(2):457–468. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Tau imaging: early progress and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(1):114–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamura N, Furumoto S, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, et al. Non-invasive assessment of Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary pathology using 18F-THK5105 PET. Brain. 2014;137:1762–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada R, Okamura N, Furumoto S, et al. Comparison of the binding characteristics of [18F]THK-523 and other amyloid imaging tracers to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villemagne VL, Furumoto S, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, et al. In vivo evaluation of a novel tau imaging tracer for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:816–826. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wechsler D. WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker JA, Hedden T, Carmasin J, et al. Amyloid-β associated cortical thinning in clinically normal elderly. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(6):1032–1042. doi: 10.1002/ana.22333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(12):2880–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mormino EC, Betensky RA, Hedden T, et al. Amyloid and APOE e4 interact to influence short-term decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2014;82(20):1760–1767. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert MS, Dekosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer‘s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. 2011:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoup TM, Yokell DL, Rice PA, et al. A concise radiosynthesis of the tau radiopharmaceutical, [(18) F]T807. J Label Compd Radiopharm. 2013;56(14):736–740. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3098. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, et al. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta neuropatholog. 2006;112(4):389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4):351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delacourte A, Sergeant N, Wattez A, et al. Tau aggregation in the hippocampal formation: an ageing or a pathological process? Exp Gerontol. 2002;37(10–11):1291–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischl B, Salat DH, van der Kouwe AJ, et al. Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S69–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logan J. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10(5):740–747. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedden T, Van Dijk KRA, Becker JA, et al. Disruption of functional connectivity in clinically normal older adults harboring amyloid burden. Journal of Neurosci. 2009;29(40):12686–12694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arriagada PV, Marzloff K, Hyman BT. Distribution of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in nondemented elderly individuals matches the pattern in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1992 Sep;42(9):1681–1688. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1992 Mar;42(3 Pt 1):631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Morris JC, Growdon JH, Hyman BT. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 1996 Jul 15;16(14):4491–4500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04491.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquie M, Normandin M, Vanderburg C, et al. Towards the validation of novel PET tracer T807 on postmortem human brain tissue samples. In: Johnson KA, Jagust WJ, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, editors. Proceedings of the 9th Human Amyloid Imaging Conference; 2015 Jan 14–16; Miami, FL. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serrano-Pozo A, Qian J, Monsell SE, et al. Examination of the clinicopathologic continuum of Alzheimer disease in the autopsy cohort of the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013 Dec;72(12):1182–1192. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. Brains with medial temporal lobe neurofibrillary tangles but no neuritic amyloid plaques are a diagnostic dilemma but may have pathogenetic aspects distinct from Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(7):774–784. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181aacbe9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, et al. Primary age-related taupathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(6):755–766. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]