Abstract

In this era of more rational therapies, substantial efforts are being made to identify optimal targets. The discovery of translocations involving the Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) receptor tyrosine kinase in a subset of non-small cell lung cancers has become a paradigm for precision medicine. Notably, ALK was initially discovered as the fusion gene in anaplastic large cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma, a disease predominantly of childhood. The discovery of activating kinase domain mutations of the full-length ALK receptor as the major cause of hereditary neuroblastoma, and that somatically acquired mutations and amplification events often drive the malignant process in a subset of sporadic tumors has established ALK as a tractable molecular target across histologically diverse tumors where ALK is a critical mediator of oncogenesis. We are now uncovering the re-expression of this developmentally regulated protein in a broader subset of pediatric cancers, providing therapeutic targeting opportunities for diseases with shared molecular etiology. This review focuses on the role of ALK in pediatric malignancies, alongside the prospects and challenges associated with the development of effective ALK-inhibition strategies.

INTRODUCTION

The Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) oncogene is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is known to be oncogenically activated either by point mutations or by chromosomal translocations, and has emerged as potentially relevant biomarker and therapeutic target in pediatric solid and hematologic malignancies. Its expression is restricted to developing neural tissue and absent from other normal tissues (1, 2), providing the opportunity for a therapeutic window using targeted small molecule and/or immunotherapeutic approaches. ALK was first described over 20-years ago as part of a genetic rearrangement in a subset of anaplastic large-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma patients (3) and was later identified to give rise to an oncogenic fusion proteins in nearly half of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (4, 5). In 2007, new ALK rearrangements were identified in 3–5% of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), corresponding to ~50,000 patients worldwide each year (6). This pivotal discovery drove early-phase clinical studies of a dual ALK/MET small molecule inhibitor, crizotinib, in pretreated patients with advanced relapsed/refractory NSCLC harboring ALK rearrangements (7). The dramatic response rates validated ALK as a therapeutic target and led to the expedited FDA approval of crizotinib in August 2011 for use in patients with relapsed ALK-translocated lung cancer. Since then, crizotinib has been approved as first-line therapy for ALK-fusion positive NSCLC, and several additional ALK inhibitors are in clinical development with remarkable activity already seen in patients who have developed resistance to crizotinib.

The identification of recurrent activating point mutations within the ALK tyrosine kinase domain in both the hereditary and sporadic form of neuroblastoma has highlighted the importance of the ALK oncogene across histologically diverse tumors. Here we review the role of ALK as a critical mediator of oncogenesis across pediatric malignancies.

ALK TRANSLOCATION-DRIVEN PEDIATRIC CANCERS

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

The ALK gene was first discovered in 1994 as a fusion oncogene with nucleophosmin (NPM) in a subset of anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL), a malignancy predominantly of childhood, from a translocation involving the ALK gene on chromosome 2p (3). Since then, multiple fusion partners forming ALK chimeric proteins have been identified in this disease, and ALK fusions have also been reported in diffuse large-B cell lymphomas (8). ALCLs represent a well-recognized and distinct subgroup of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that account for 10–15% of all childhood lymphomas (9, 10), and are characterized by the expression of the membrane receptor CD30, a member of the nerve growth factor/tumor necrosis factor receptor family (11). The vast majority of pediatric cases harbor the characteristic ALK gene translocation (83% versus 31% in adult ALCL) with overexpression of the ALK protein, and it is possible that variant ALK fusion transcripts may identify biologically and clinically distinct subgroups of ALCL (12, 13). These fusion proteins can all be recognized immunohistochemically on fixed tissue as well as by molecular and cytogenetic techniques. Interestingly, primary cutaneous ALCL is ALK negative and thought to be an unrelated disease entity. Children with advanced-stage ALCL have not fared well, with disease-free survivals in the range of 50–80% using chemotherapeutic regimens varying in duration and intensity (10, 14).

Because ALK is not expressed in most normal cells, the possibility exists that the ALK protein would be the target of an immune response, which could explain the paradox that ALK-positive ALCL is highly aggressive histologically but has a better prognosis than other large cell lymphomas. The possibility that ALK proteins are immunogenic was investigated by Pulford and colleagues, and circulating antibodies against NPM-ALK protein were found to be present in all ALK-positive ALCL patients studied while several patients also had antibodies recognizing normal ALK protein (15). These data suggest that the presence of anti-ALK antibodies may be relevant to the more favorable prognosis of ALK-positive ALCL.

While numerous clinical studies have used a wide range of chemotherapeutic strategies, no intervention has been able to improve on the approximate failure rate of 25–30% that exists regardless of treatment strategy. In addition, disease progression while receiving chemotherapy portends a very poor prognosis, with only 25% expected to survive even with aggressive salvage therapy, including allogeneic transplant (16, 17). Quite remarkably, the Children’s Oncology Group phase 1 trial of single-agent crizotinib revealed marked anti-tumor activity in eight out of nine patients with relapsed ALK-translocated ALCL at a range of doses (18). Crizotinib was well tolerated without evidence of cumulative toxic effects. Nine patients with ALK-translocated ALCL were enrolled, all of who received previous multi-agent chemotherapy, and seven had a complete and sustained response with crizotinib monotherapy. As we await the results from the phase 2 trial and an update on the status of durability of response in the ALCL patients treated on the phase 1, this robust activity has set the stage for the current COG pilot phase 2 trial that will determine the toxicity and efficacy of integrating crizotinib with standard chemotherapy in newly diagnosed ALCL patients (NCT01979536) with the goal of preventing relapse, especially on-therapy progression, and reducing toxicity in order to have a significant impact on overall survival.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor

In solid tumors, ALK fusions were first reported in Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors (IMTs) (19), a rare mesenchymal tumor that can occur at any age but has a predilection for children and adolescents (20). These soft tissue tumors most commonly involve the lung, abdomen/pelvis and retroperitoneum and the mainstay of curative therapy is complete surgical resection. Systemic therapy options such as cytotoxic chemotherapy or anti-inflammatory agents are limited for patients with unresectable, recurrent or metastatic disease. Approximately 50% of IMTs express the ALK protein by immunohistochemistry (21, 22) as a result of numerous structural rearrangements involving the ALK gene that have been described (4, 5, 23, 24). Objective and sustained responses to crizotinib have been reported in children with IMTs (18), supporting the dependence of ALK-rearranged tumors on ALK-signaling and demonstrating the significance of identifying this target. Notably, recent targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) efforts have defined this disease as one that is largely a kinase-fusion driven malignancy. Lovly and colleagues identified novel ALK gene fusions in only samples that tested negative for ALK expression by IHC, as well as ALK fusions with various 5′ gene fusion partners and ALK fusions with noncanonical fusion breakpoints (25). Because these patients are likely to benefit from ALK inhibition strategies, it is now essential to incorporate these atypical but recurrent fusions into diagnostic sequencing platforms, and to move away from IHC alone for identification of ALK-driven IMTs.

PEDIATRIC CANCERS HARBORING ALK MUTATIONS: NEUROBLASTOMA

Despite major enhancements in treatment approaches over the past several decades, neuroblastoma remains a leading cause of childhood cancer deaths and survivors are left with long-term side effects (26). The discovery of germline missense point mutations in the intact ALK oncogene as the genetic etiology of familial neuroblastoma (27, 28), and of somatically acquired mutations that predict for inferior outcome in patients with the most aggressive form of this disease (29), has positioned ALK as the only mutated oncogene tractable for targeted therapy in this disease. ALK mutations are identified in 8% of neuroblastoma patients and span the entire spectrum of disease, including stage 4 disease, congenital cases (<30 days old), and adolescents/young adults (29). Within the high-risk subset of patients, ALK aberrations are found in 14% (10% mutations, 4% amplification), and the presence of an ALK aberration is a biomarker of inferior outcome (29). This provides an opportunity to integrate ALK-targeted therapy for a subgroup of patients with a poor prognosis whose tumors harbor a molecular vulnerability that can be targeted therapeutically. However, despite our increasing knowledge of how to treat ALK-rearranged lung cancer and other ALK-rearranged malignancies, inhibition of full-length mutated ALK remains a therapeutic challenge. Interestingly, the most frequently identified secondary mutations in ALK-fusion positive NSCLC at time of acquired crizotinib resistance are L1196M (rarely identified in NB) and G1269A (Table 1) (30). These observations intimate that certain molecular contexts enable differential sensitivity to direct ALK kinase inhibition over others, suggesting a context-dependent role for ALK in driving response and mechanisms of resistance.

Table 1.

Spectrum and frequency of ALK mutations identified in diagnostic neuroblastoma tumors.

| ALK Mutation | Frequency in ALK-mutant tumors | Functional Significance | Identified in Lung Cancer Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1275Q/L | 45% | Transforming | |

| F1174L/V/C | 30% | Transforming | yes |

| F1245V/C | 12% | Transforming | |

| R1060H | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| M1166R | 1.60% | Transforming | |

| I1170N/S | 1.60% | Transforming | |

| I1171N | 0.80% | Transforming | yes (I1171T) |

| Y1278S | 0.80% | Transforming | |

| G1286R | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| L1240V | 0.80% | Transforming | |

| G1128A | 0.80% | Transforming | |

| T1151M | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| I1183T | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| R1192P | 0.80% | Transforming | |

| L1196M | 0.80% | Transforming | yes |

| A1200V | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| D1270G | 0.80% | Not Transforming | G1269A, just proximal |

| L1204F | 0.80% | Not Transforming | G1202R, just proximal |

| R1231Q | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| I1250T | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| T1343I | 0.80% | Not Transforming | |

| D1349H | 0.80% | Not Transforming |

Our work – and that of others – has been successful in positioning ALK as the first tractable oncogene for targeted therapy in neuroblastoma, revealing that activating mutations are oncogenic drivers in some cases (27, 28, 31, 32). In developing approaches to act on this knowledge, discerning non-activating from activating mutations is extremely important, and identifying non-activating mutations is one of the most central unmet challenges in progress towards personalized medicine (33). Preclinical data argue that not all clinically observed ALK mutations are functionally relevant as ALK activators (Table 1), and further, that some ALK-activating mutations also cause primary resistance to direct ALK kinase inhibition with crizotinib (29). We find that 1 out of 11 patients with an ALK mutation harbors a ‘silent’ mutation (Table 1). This highlights the importance of bringing mechanistic considerations to bear that can distinguish ‘silent’ mutations in ALK from those that are activating, so as to determine which next-generation ALK inhibitor has the broadest applicability across mutants, and so as to accurately distinguish the patients that are good candidates for ALK-targeted therapy. In the case of EGFR in lung cancer, mutations have now been found at ~70% of sites in the kinase (34). Determining which are not relevant, which are surprisingly common, is as important as identifying those that are functional. Moreover, identifying which ALK variants are crizotinib resistant and which are not (among those with activating mutations) has immediate clinical relevance as we begin to use ALK sequence to guide patient treatment. This implies that not all patients harboring an ALK mutation are predicted to respond to crizotinib.

Consistent with this, while marked anti-tumor activity was observed in pediatric patients with diseases harboring ALK translocations, far fewer objective responses were seen in patients with ALK-mutant neuroblastoma in the Children’s Oncology Group Phase 1 trial of crizotinib (18). Objective responses were seen in two patients with refractory neuroblastoma, both harboring germline ALK R1275Q mutations. Additionally, one patient with unknown ALK status had a complete response and five others had prolonged stable disease, three of which remain on treatment. This uncovers a primary resistance to ALK inhibition in patients who have an appropriate genetic abnormality but fail to respond. We speculate as to which of the newer generation of ALK inhibitors is likely to be most useful for which sets of mutations. Recent work from the Engelman group suggests that ceritinib would be more useful for I1171 and L1196 mutations (30), and the new PF-06463922 compound may be best for F1174 mutations (35). These findings underscore the need to develop a responder hypothesis for therapeutic stratification of newly diagnosed patients with ALK mutant neuroblastoma, to discover robust biomarkers of drug sensitivity and mechanisms of resistance to ALK inhibition, and to define circumvention strategies in the clinic in order to maximize patient benefit. Additionally, more precise studies of clonal evolution in sequential samples form patients with neuroblastoma have revealed an emergence of ALK mutations at the time of relapse, a finding of utmost clinical importance given the development of ALK inhibition strategies (36).

ALK AS AN IMMUNOTHERAPY TARGET IN OTHER CHILDHOOD CANCERS

Although our understanding of the biology of childhood cancer has advanced substantially, new targeted therapies have not yet significantly improved outcomes or allowed the community to develop less toxic standard therapies. Recent comprehensive genomic analyses have yielded the sobering conclusion that actionable recurrent somatic mutations are rare in pediatric cancers (37, 38), raising the prospect that we need to move beyond small molecules targeting mutant kinases if we want to substantially improve outcomes using precisely developed therapies. We now have the potential to leverage genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of childhood cancers to identify cell surface antigens expressed on tumor cells for development of antibody-based immunotherapies. Below are a few examples where ALK has been found to be re-expressed and provides the opportunity for immunotherapeutic targeting.

Neuroblastoma

It has been firmly established that activation by mutation or amplification renders the intact ALK receptor tyrosine kinase an attractive therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. ALK mRNA expression (39) and native ALK protein expression measured by IHC (40, 41) have been proposed as biomarkers of mutation-independent ALK activation. While ALK expression levels are significantly higher in tumor cells with activating ALK mutations (point mutations and amplification), no direct correlation has been found between ALK levels and constitutive activation of the ALK protein- hence, validated genetic alterations remains the hallmark that render neuroblastoma cells susceptible to kinase inhibition. However, neuroblastoma cells almost ubiquitously express ALK on the cell surface, with expression restricted to tumor cells, suggesting that ALK is an optimal tumor antigen for immunotherapy (1, 42). Given the success of therapeutic antibodies that target oncogenic RTKs such as EGFR and HER2/Neu in other cancers, we propose that a similar approach should be developed for specifically targeting ALK in neuroblastoma. The development of ALK-targeted antibodies as a potential therapeutic approach in neuroblastoma may be complicated by the challenges of threshold receptor density, which for ALK varies substantially in this disease, and may require alternative approaches such as antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-based therapies to effectively bind to an antigen with selective cell surface expression.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS) are the most common soft tissue sarcomas of childhood (43) with two main histological subtypes: Embryonal RMS (60 – 70%) and alveolar RMS (20–30%). ARMS is characterized by the t(2;13) translocation (PAX3-FOXO1) in the majority, or a t(1;13) translocation (PAX7-FOXO1), and characteristically have a more aggressive clinical course. While treatment advances have yielded dramatic improvements in survival, patients with metastatic disease have a poor prognosis (44). Gene-expression profiling studies have identified distinct molecular signatures, with a postulated association between translocation-positive ARMS and ALK overexpression (45). Additionally, prior studies have showed that ARMS were more commonly immunopositive for native ALK protein expression than other subtypes (46, 47), with the largest series (n=116) showing a clear difference in ALK reactivity between alveolar (69%) and other (4%) (48). There have been no reports of recurrent activating point mutations, translocations, or high-level amplifications in these tumors, suggesting that the differential ALK staining is possibly physiologic or from ligand participation, and it is unlikely to render this tumor subtype amenable to therapeutic targeting using small molecules such as crizotinib. While the role of ALK as an oncogenic therapeutic target remains to be validated in RMS, we can postulate a role for targeting ALK on the cell surface of these tumors using immunotherapeutic approaches.

Other childhood cancers

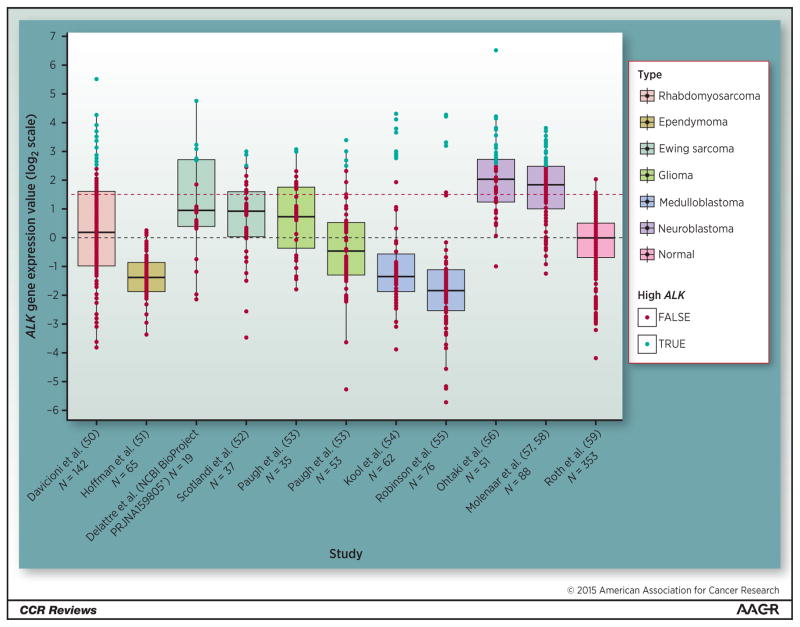

We have developed a method for identifying tumor antigen candidates by leveraging publically available microarray gene expression databases of pediatric cancer and normal tissues, and other studies have shown a significant correlation between mRNA and protein levels (49). Averaging ALK expression levels from individual tumor samples according to histotype and comparing to average normal tissue expression levels has provided the opportunity to define a broader role for ALK in pediatric cancers (Figure 1) (50–59).

Figure 1.

Boxplots of ALK mRNA expression displayed across a set of pediatric tumor microarray studies and one normal microarray study encompassing a variety of tissues. Dashed black line indicates median normal expression. Dashed red line indicates 99th percentile of normal tissue which. Points shaded in blue represent patient samples with 2-fold higher levels of ALK expression as compared with 99th percentile of normal tissue level. The microarray data was MAS5 normalized and log2 transformed. Boxplot figure was generated using the ggplot2 package (Wickham, Hadley. Ggplot2. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009. Print). Normalization and analysis was done using the R statistical language and Bioconductor framework. *Accession number GSE 37371.

In analyzing these data, it has become clear that re-expression of the developmentally regulated ALK protein is present across a subset of pediatric tumors, with a percentage of tumor samples showing substantially higher expression than normal tissues (Figure 1). This distinction is especially important in pediatric cancers where there is the clear concern that targeting receptors that may be present on normal tissues that are crucial to development, even at low levels, could be harmful. Notably, in addition to neuroblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma, ALK is differentially expressed at high levels in subsets of medulloblastomas, gliomas, and Ewing sarcomas. The wide distribution of this target provides an opportunity for development of immune targeting strategies that could be safely achieved without loss of host integrity. How a tumor antigen is targeted by the immune system may be as important as the expression level of the antigen on various tissues.

While antibody-derived therapeutics targeting the ALK receptor at the cell surface is likely to be an approach that will be shared among several pediatric tumors, the safety of targeting ALK in this way has yet to be demonstrated. We have established that there is sufficient differentiation between cancer and normal host tissue using neuroblastoma as a model (1), suggesting that ALK can be readily targeted, though we do not yet have an understanding of the cell surface expression necessary for effective targeting. A large-scale effort will be necessary to definitively credential the role of ALK as a tumor antigen in various pediatric tumors, and to systematically evaluate cell-surface density as one of likely several biomarkers that supports its potential for immunotherapy. The broad role of ALK in pediatric malignancies should encourage a new look at common adult cancers.

CONCLUSIONS and FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Childhood cancer represents a rare disease and drug development remains challenging in part because of the limited availability of patient cohort and the limited marketability of drugs even when they are successful. This paradigm is now shifting as we face the opportunity to develop rational targeted therapies for small subsets of patients, and drug trials are beginning to group patients by shared molecular etiology across multiple diseases. A demonstrative example of this is the Children’s Oncology Group trial of crizotinib that enrolled a molecularly selected cohort of patients with malignancies known to display a dependency on the ALK oncogene (18). Marked anti-tumor activity was observed in patients with relapsed/refractory ALCL with complete and sustained responses reported, supporting the dependence of ALK-rearranged tumors on ALK signaling. Similarly, robust responses were reported for patients with IMTs, providing an effective and well-tolerated therapeutic strategy for these patients. However, numerous objective responses to crizotinib were not observed in patients with ALK-mutant neuroblastoma. The patients in this trial were heavily pretreated, in the late stages of their disease, and the increased incidence of loss of p53 function after the selective pressure of chemotherapy yields multi-drug resistant disease (60). Strikingly, little is known about the genome of neuroblastoma at the time of relapse following intense cytotoxic chemotherapy, in part because patients are rarely subjected to a tumor biopsy. There is some evidence to suggest that the neuroblastoma genome evolves extensively under the selective pressure of chemotherapy, and we hypothesize that targetable somatic mutations are enriched in this population and mediate therapy resistance even in the presence of an activated kinase. Deep-sequencing approaches have provided insight into the clonal evolution of this disease and revealed that ALK mutations may in fact occur as subclones present at low-level, with secondary expansion at time of relapse (36). This provides strong rationale for performing biopsies and genomic characterization of relapsed neuroblastomas, with the prospect for direct patient benefit.

As high-throughput sequencing approaches generate broad cataloguing of genetic variations in cancer, we must be able to distinguish disease-causing or functionally relevant mutations from non-pathogenic passenger variants. This is critical in order to maximize clinical benefit, and false ascription of pathogenicity will result in severe consequences. As the volume of patient sequencing data accumulates, it is critical not only to deliver to the research and clinical community a validated catalog of these variations, but also to correlate these with oncogenic potency, and identify which targeted inhibitors effectively inhibit. The recent discovery and functional validation of oncogenic mutations in the extracellular domain of ALK in leukemia (61) not only broadens the role of this oncogene across histologically diverse tumors, but also presents an exciting therapeutic opportunity in rare subsets of patients based on shared molecular etiology.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Pichai Raman, Computational Biologist in the Department of Biomedical and Health informatics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, for analysis of the mRNA expression data across a set of pediatric microarray studies, and for visualization of this data in figure form.

Grant Support

Y.P. Mosse was supported in part by the NIH under award number R01CA140198 and by a U.S. Army Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program grant (W81XWH-12-1-0486).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts.

References

- 1.Carpenter EL, Haglund EA, Mace EM, Deng D, Martinez D, Wood AC, et al. Antibody targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase induces cytotoxicity of human neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2012;31:4859–67. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamant L, Pulford K, Bischof D, Morris SW, Mason DY, Delsol G, et al. Expression of the ALK tyrosine kinase gene in neuroblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1711–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris SW, Kirstein MN, Valentine MB, Dittmer KG, Shapiro DN, Saltman DL, et al. Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Science. 1994;263:1281–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8122112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Dvorak C, Henkle C, Ellingham T, Perlman EJ. Recurrent involvement of 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2776–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence B, Perez-Atayde A, Hibbard MK, Rubin BP, Dal Cin P, Pinkus JL, et al. TPM3-ALK and TPM4-ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:377–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64550-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent C, Do C, Gascoyne RD, Lamant L, Ysebaert L, Laurent G, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a rare clinicopathologic entity with poor prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4211–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandlund JT, Downing JR, Crist WM. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1238–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seidemann K, Tiemann M, Schrappe M, Yakisan E, Simonitsch I, Janka-Schaub G, et al. Short-pulse B-non-Hodgkin lymphoma-type chemotherapy is efficacious treatment for pediatric anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a report of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster Group Trial NHL-BFM 90. Blood. 2001;97:3699–706. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein H, Foss HD, Durkop H, Marafioti T, Delsol G, Pulford K, et al. CD30(+) anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a review of its histopathologic, genetic, and clinical features. Blood. 2000;96:3681–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins SL, Pickering D, Lowe EJ, Zwick D, Abromowitch M, Davenport G, et al. Childhood anaplastic large cell lymphoma has a high incidence of ALK gene rearrangement as determined by immunohistochemical staining and fluorescent in situ hybridisation: a genetic and pathological correlation. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:624–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM, Ullrich F, Jaffe ES, Connors JM, et al. ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2008;111:5496–504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brugieres L, Deley MC, Pacquement H, Meguerian-Bedoyan Z, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Robert A, et al. CD30(+) anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in children: analysis of 82 patients enrolled in two consecutive studies of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology. Blood. 1998;92:3591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pulford K, Falini B, Banham AH, Codrington D, Roberton H, Hatton C, et al. Immune response to the ALK oncogenic tyrosine kinase in patients with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2000;96:1605–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woessmann W, Peters C, Lenhard M, Burkhardt B, Sykora KW, Dilloo D, et al. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory anaplastic large cell lymphoma of children and adolescents--a Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster group report. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:176–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woessmann W, Zimmermann M, Lenhard M, Burkhardt B, Rossig C, Kremens B, et al. Relapsed or refractory anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents after Berlin-Frankfurt-Muenster (BFM)-type first-line therapy: a BFM-group study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3065–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosse YP, Lim MS, Voss SD, Wilner K, Ruffner K, Laliberte J, et al. Safety and activity of crizotinib for paediatric patients with refractory solid tumours or anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a Children’s Oncology Group phase 1 consortium study. Lancet Oncology. 2013;14:472–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Dvorak C, Henkle C, Ellingham T, Perlman EJ. Recurrent involvement of 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2776–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: where are we now? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:428–37. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.049387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cessna MH, Zhou H, Sanger WG, Perkins SL, Tripp S, Pickering D, et al. Expression of ALK1 and p80 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and its mesenchymal mimics: a study of 135 cases. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:931–8. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000026615.04130.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook JR, Dehner LP, Collins MH, Ma Z, Morris SW, Coffin CM, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) expression in the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a comparative immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1364–71. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cools J, Wlodarska I, Somers R, Mentens N, Pedeutour F, Maes B, et al. Identification of novel fusion partners of ALK, the anaplastic lymphoma kinase, in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:354–62. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Togashi Y, Soda M, Hatano S, Inamura K, et al. KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3143–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovly CM, Gupta A, Lipson D, Otto G, Brennan T, Chung CT, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harbor multiple potentially actionable kinase fusions. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:889–95. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Lequin D, Brugieres L, Ribeiro A, de Pontual L, Combaret V, et al. Somatic and germline activating mutations of the ALK kinase receptor in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:967–70. doi: 10.1038/nature07398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosse YP, Laudenslager M, Longo L, Cole KA, Wood A, Attiyeh EF, et al. Identification of ALK as a major familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Nature. 2008;455:930–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bresler SC, Weiser DA, Huwe PJ, Park JH, Krytska K, Ryles H, et al. ALK Mutations confer differential oncogenic activation and sensitivity to ALK inhibition therapy in neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:682–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friboulet L, Li N, Katayama R, Lee CC, Gainor JF, Crystal AS, et al. The ALK inhibitor ceritinib overcomes crizotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:662–73. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Takita J, Choi YL, Kato M, Ohira M, Sanada M, et al. Oncogenic mutations of ALK kinase in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:971–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George RE, Sanda T, Hanna M, Frohling S, Luther W, 2nd, Zhang J, et al. Activating mutations in ALK provide a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:975–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, Rehm HL, Shendure J, Abecasis GR, et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014;508:469–76. doi: 10.1038/nature13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;15:415–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson TW, Richardson PF, Bailey S, Brooun A, Burke BJ, Collins MR, et al. Discovery of (10R)-7-amino-12-fluoro-2,10,16-trimethyl-15-oxo-10,15,16,17-tetrahydro-2H-8,4-(m etheno)pyrazolo[4,3-h][2,5,11]-benzoxadiazacyclotetradecine-3-carbonitrile (PF-06463922), a macrocyclic inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and c-ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) with preclinical brain exposure and broad-spectrum potency against ALK-resistant mutations. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4720–44. doi: 10.1021/jm500261q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schleiermacher G, Javanmardi N, Bernard V, Leroy Q, Cappo J, Rio Frio T, et al. Emergence of new ALK mutations at relapse of neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2727–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parsons DW, Li M, Zhang X, Jones S, Leary RJ, Lin JC, et al. The genetic landscape of the childhood cancer medulloblastoma. Science. 2011;331:435–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1198056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pugh TJ, Morozova O, Attiyeh EF, Asgharzadeh S, Wei JS, Auclair D, et al. The genetic landscape of high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:279–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulte JH, Bachmann HS, Brockmeyer B, Depreter K, Oberthur A, Ackermann S, et al. High ALK receptor tyrosine kinase expression supersedes ALK mutation as a determining factor of an unfavorable phenotype in primary neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5082–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duijkers FA, Gaal J, Meijerink JP, Admiraal P, Pieters R, de Krijger RR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor response in neuroblastoma is highly correlated with ALK mutation status, ALK mRNA and protein levels. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2011;34:409–17. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Passoni L, Longo L, Collini P, Coluccia AM, Bozzi F, Podda M, et al. Mutation-independent anaplastic lymphoma kinase overexpression in poor prognosis neuroblastoma patients. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7338–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwahara T, Fujimoto J, Wen D, Cupples R, Bucay N, Arakawa T, et al. Molecular characterization of ALK, a receptor tyrosine kinase expressed specifically in the nervous system. Oncogene. 1997;14:439–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ognjanovic S, Linabery AM, Charbonneau B, Ross JA. Trends in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma incidence and survival in the United States, 1975–2005. Cancer. 2009;115:4218–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDowell HP, Foot AB, Ellershaw C, Machin D, Giraud C, Bergeron C. Outcomes in paediatric metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: results of The International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) study MMT-98. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1588–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson D, Missiaglia E, de Reynies A, Pierron G, Thuille B, Palenzuela G, et al. Fusion gene-negative alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is clinically and molecularly indistinguishable from embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2151–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corao DA, Biegel JA, Coffin CM, Barr FG, Wainwright LM, Ernst LM, et al. ALK expression in rhabdomyosarcomas: correlation with histologic subtype and fusion status. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12:275–83. doi: 10.2350/08-03-0434.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pillay K, Govender D, Chetty R. ALK protein expression in rhabdomyosarcomas. Histopathology. 2002;41:461–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida A, Shibata T, Wakai S, Ushiku T, Tsuta K, Fukayama M, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase status in rhabdomyosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:772–81. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orentas RJ, Yang JJ, Wen X, Wei JS, Mackall CL, Khan J. Identification of cell surface proteins as potential immunotherapy targets in 12 pediatric cancers. Front Oncol. 2012;2:194. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davicioni E, Anderson MJ, Finckenstein FG, Lynch JC, Qualman SJ, Shimada H, et al. Molecular classification of rhabdomyosarcoma--genotypic and phenotypic determinants of diagnosis: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:550–64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoffman LM, Donson AM, Nakachi I, Griesinger AM, Birks DK, Amani V, et al. Molecular sub-group-specific immunophenotypic changes are associated with outcome in recurrent posterior fossa ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:731–45. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scotlandi K, Remondini D, Castellani G, Manara MC, Nardi F, Cantiani L, et al. Overcoming resistance to conventional drugs in Ewing sarcoma and identification of molecular predictors of outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2209–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paugh BS, Qu C, Jones C, Liu Z, Adamowicz-Brice M, Zhang J, et al. Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3061–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kool M, Koster J, Bunt J, Hasselt NE, Lakeman A, van Sluis P, et al. Integrated genomics identifies five medulloblastoma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures and clinicopathological features. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robinson G, Parker M, Kranenburg TA, Lu C, Chen X, Ding L, et al. Novel mutations target distinct subgroups of medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488:43–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohtaki M, Otani K, Hiyama K, Kamei N, Satoh K, Hiyama E. A robust method for estimating gene expression states using Affymetrix microarray probe level data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Molenaar JJ, Koster J, Ebus ME, van Sluis P, Westerhout EM, de Preter K, et al. Copy number defects of G1-cell cycle genes in neuroblastoma are frequent and correlate with high expression of E2F target genes and a poor prognosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:10–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molenaar JJ, Koster J, Zwijnenburg DA, van Sluis P, Valentijn LJ, van der Ploeg I, et al. Sequencing of neuroblastoma identifies chromothripsis and defects in neuritogenesis genes. Nature. 2012;483:589–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roth RB, Hevezi P, Lee J, Willhite D, Lechner SM, Foster AC, et al. Gene expression analyses reveal molecular relationships among 20 regions of the human CNS. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:67–80. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keshelava N, Zuo JJ, Chen P, Waidyaratne SN, Luna MC, Gomer CJ, et al. Loss of p53 function confers high-level multidrug resistance in neuroblastoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6185–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maxson JE, Davare MA, Luty SB, Eide CA, Chang BH, Loriaux MM, et al. Therapeutically targetable ALK mutations in leukemia. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2146–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]