Abstract

Context:

Dry eye is a very common as well as under-diagnosed ocular disorder. It is not only troublesome in terms of its symptoms but also imposes a great financial burden.

Aims:

To determine the prevalence of dry eye in ophthalmology out-patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital and its association with various clinico-epidemiological factors.

Settings and Design:

A hospital-based study at a Tertiary Care Center was conducted including 400 out-patients of age 40 years and above.

Materials and Methods:

Patients were consecutively selected and underwent a routine ophthalmological examination along with tear film break-up time (TBUT) as a screening tool for detecting the presence of dry eye.

Statistical Analysis:

We performed a descriptive, univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence interval.

Results:

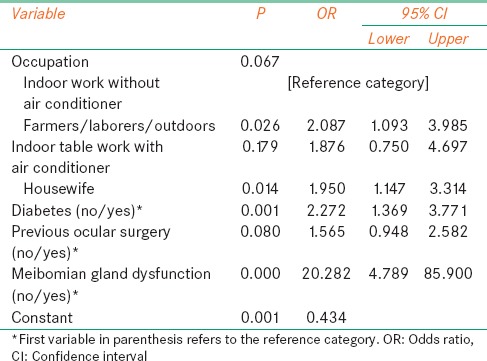

The mean age of the study population was 58.6 years. The overall prevalence of dry eye was found to be 54.3%. An association was found between dry eye prevalence and outdoor workers, participants working indoor using air conditioners, housewives, diabetics, patients who have undergone previous ocular surgery and those with meibomian gland dysfunction.

Conclusions:

Dry eye is a very common condition with a high prevalence among the elderly. We recommend the screening of all out-patients by TBUT, which is a simple test to perform and examination of lids for meibomian gland disease, which if present can be treated. Further studies are needed to establish uniform diagnostic criteria for dry eye, which will help to get more concrete prevalence data, as well as its etiological factors.

Keywords: Dry eye, meibomian gland dysfunction, tear film breakup time

Introduction

In 2007, the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) revised the original definition and classification scheme of dry eye disease (DED) and developed a new definition based on aetiology, mechanism, and severity of the disease. The term dry-eye syndrome according to DEWS has been defined as “a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear-film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface”.[1] Dry eye refers to disorders of the tear film due to reduced tear production and/or excessive tear evaporation associated with symptoms of ocular discomfort.[2]

Patients with dry eye often complain of pain, heaviness, foreign body sensation, redness, photophobia and reflex watering due to corneal irritation. Because the tear film in dry eye patients is unstable and incapable of maintaining the protective qualities that are necessary for its structure and function, patients experience the symptoms of discomfort associated with dry eye, which are burning, stinging, grittiness, foreign body sensation, tearing, ocular fatigue, and dryness. Patients may complain of symptoms of dry eye in the presence or absence of signs of the disease.[3]

A more recent area of study in dry eye is the implications for visual function and its quality.[4] The decreased blink rate experienced during visual function tasks (for example extended computer use, reading, watching TV, working on microscope) can exacerbate dry eye and its signs and symptoms (like blurred vision, ocular surface staining, short tear film break-up time [TBUT]), which in turn, can limit patients’ visual functioning capabilities.[5]

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving 400 patients who visited the Ophthalmology Outpatient Department at a 600-bed Rural Teaching Tertiary Care Center, with various complaints which may or may not involve dry eye symptoms. Our study sample includes mixed population of both rural and urban areas. We recruited our participants over a period of 2 months. Patients of age 40 years and above were consecutively selected on 2 fixed days of a week and administered a structured questionnaire.[6] Patients with ocular surface infections, foreign body, extensive ocular surface pathologies and those who had undergone an ocular surgery within 2 months were excluded from the study. The questionnaire included demographic, medical, lifestyle data and symptoms[7] of dry eye such as dryness, grittiness, burning, stickiness, heaviness, itching and watering.[8] The above symptoms were found to be some of the leading and troublesome ones as reported by previous studies and other validated questionnaires.[9] The questionnaire was administered by a single trained ophthalmology resident in vernacular language while the ocular examination was carried out by an ophthalmologist. We obtained a written informed consent from all our participants.

All participants underwent a general ophthalmic assessment along with slit lamp examination and TBUT. TBUT was performed in all participants by a single observer.

Tear film break-up time was used to assess the stability of the precorneal tear film. It is a global marker for DED, easy and rapid to perform.[10] It is considered to be a reliable and repeatable test for dry eye and is minimally invasive.[11] It is also correlated with the tear meniscus during normal blinking.[12] TBUT has been reported to be low in different types of dry eye, including keratoconjunctivitis sicca, mucin deficiency and meibomian gland disease.[13] It was measured by applying fluorescein dye in the inferior cul-de-sac followed by evaluating the stability of the precorneal tear film.[14] Test was conducted at room temperature with fans switched off, and all readings were taken by a single observer. We performed this test by moistening a fluorescein strip (Contacare Ophthalmics and Diagnostics, Baroda, India) with sterile normal saline and applying it to the inferior fornix. After several blinks, patient was instructed not to blink further, and the tear film was examined using a broad beam of the slit lamp with a blue filter. The time lapse between the last blink and the appearance of the first randomly distributed dark discontinuity in the fluorescein stained tear film was taken as the TBUT. TBUT was measured before instillation of any eye drops. Patients with TBUT < 10 s were diagnosed as having dry eye.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed first, followed by a univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis. For the purpose of analysis, the average of TBUT of both the eyes was considered. The association between demographic variables, addictions, systemic diseases (diabetes, hypertension and arthritis), dry eye symptoms and DED was evaluated using Pearson Chi-squared tests. For statistical analyses, commercially available software SPSS for Windows (version 14.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used. Multivariable analysis was performed to determine the strength of association between dry eye and its contributing factors. Using the logistic regression model, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the same.

Results

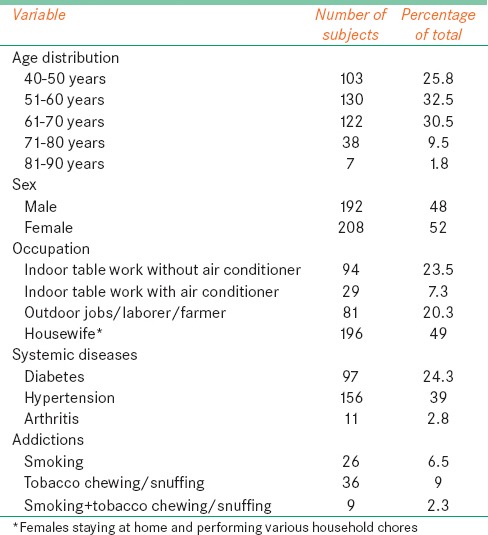

Of the 417 consecutive patients, 400 patients agreed to participate in the study (4% drop out rate). Mean age of the study population was 58.6 years. Sample consisted of 52% females, and the majority of them were housewives. Tobacco chewing was found to be the most prevalent addiction among the study population (9%).

Table 1 represents the baseline characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical profile of study population (n=400)

The overall prevalence of dry eye was found to be 54.3% of the sample size of 400 participants of age 40 years and above. The prevalence of dry eye was found to be maximum in the elderly. It was 67.3% in participants aged 71 years and above. Fifty-one percent males and 57.2% of females had dry eye disorder. This depicts a higher prevalence of dry eye disorder among the female population.

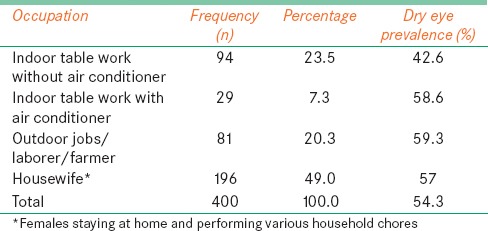

We assessed the prevalence of dry eye among various occupation groups. Farmers and those doing outdoor jobs have the highest prevalence of dry eye, which is 59.3% while those doing indoor jobs without the use of air conditioners have the least prevalence of dry eye [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of dry eye among various occupation groups

Our area of study is one of the key places for tobacco production and the study population thus comprises of tobacco addicts either in the form of chewing, snuffing or smoking. About 8.8% of the population comprised of tobacco smokers while 11.3% consumed tobacco in the form of chewing or snuffing. Sixty percent of the smokers and tobacco chewers had dry eye.

The effect of systemic disorders like diabetes mellitus (mainly type 2), hypertension and arthritis with dry eye was studied. Sixty-seven percent of the diabetic patients suffered from dry eye. This is quite high as compared to the dry eye prevalence in hypertensive patients (51%) and those suffering from arthritis (55%).

We estimated the prevalence of dry eye among patients having meibomian gland disease. Eighteen percent of the study population had blocked meibomian glands, which were diagnosed on slit lamp examination. We found 95.1% prevalence of dry eye among these patients. This highlights the importance of examination of meibomian glands and associated lid disorders in routine patients.

Sample consisted of 6.3% glaucoma patients who were on various topical antiglaucoma medications, out of which 72% had dry eye.

There were 23.5% patients who had undergone a previous intraocular surgery (mostly cataract extraction). Out of them, 60.4% suffered from dry eye. Patients who had undergone surgery within the last 2 months were excluded from the study.

Only two patients were soft contact lens users and both of them had dry eye disorder.

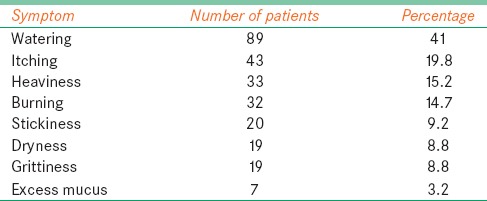

The participants were asked if they had one or more of the dry eye symptoms such as dryness, grittiness, burning, excess mucus, stickiness, heaviness, itching and watering. These symptoms were compared with TBUT readings. Among the various symptoms for which patients visited our Outpatient Department watering was the most common complaint (33.5%) followed by itching sensation (15%). Of the total study population, patients who complained of dryness and excessive mucoid discharge had the maximum prevalence of dry eye (82.6% and 87.5% respectively). Of the patients who had dry eye, watering (41%) and itching (19.8%) were the most common symptoms [Table 3].

Table 3.

Presenting symptoms among dry eye patients (n=217)

Among the asymptomatic patients, 24.1% had dry eye. This reflects the subclinical dry eye patients who later on may come back with one or more of the dry eye symptoms.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis showed an association between dry eye prevalence and outdoor workers, participants working indoor using air conditioner, housewives, diabetics, patients who have undergone previous ocular surgery and those with meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showing association of dry eye

Discussion

Dry eye prevalence as estimated in this study is around 54% in patients visiting the Outpatient Department at a Tertiary Care Center. Guillon et al.[15] have shown in a study in United Kingdom that the tear film evaporation is significantly higher in subjects above the age of 45 years. An intact and efficient lipid layer in the tear film is required to prevent the evaporative loss of tear film. This lipid layer is thinner and less efficient in older subjects and particularly females. There is destabilization associated with significant changes in the tear lipid layer leading to less protection from evaporation in the older population.[16] These findings are consistent with the previous studies by Shaumberg,[17] Moss et al.[18] which emphasize an increased prevalence of dry eye in the elderly, particularly women.

The prevalence of dry eye disorder had been very variable as found from the previous population based as well as hospital-based studies. Studies have reported the prevalence of dry eye to be varying from 5% to as high as 73.5%.[19,20] In a survey conducted by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, respondents reported that around 30% of patients seeking treatment from an ophthalmologist have symptoms consistent with DED.[21] Another update from the international DEWS stated that the global prevalence of dry eye is about 17% while several other studies show a higher prevalence of approximately 30% in people of Asian descent.[22] A retrospective study conducted at Miami and Broward Veterans Affairs eye clinics estimated a prevalence of 22% DED in females compared to 12% in males.[23] A study conducted in Korea reported a prevalence of 33.2%.[24] The overall prevalence of dry eye among patients of age 40 years and above in our study population is 54.3% which is quite higher than that found in other similar studies. This may reflect the effect of tropical whether conditions in our area of study and other population characteristics of the study population. Another reason for this disparity among the reported prevalence among various studies may be a lack of standardized diagnostic definition.

About 20% of our study population consisted of farmers and laborers working in adverse environmental conditions for long hours. They are exposed to excessive heat, sunlight, dust and wind. Further, their exposure to fertilizers and insecticides cannot be ignored. A poor economic condition as well as lack of awareness in this group of people prevents them from adopting protective equipment during work. We found the prevalence of dry eye to be 59.3% in this study population. Khurana et al.[25] too reported an increased risk of dry eye among farmers and laborers (32% and 28% respectively of the dry eye patients) probably due to excessive exposure to adverse environment. This emphasizes the need for creating awareness among the farmers to adopt protective measures during work. This might not altogether prevent the incidence of dry eye, but this is will help in delaying this condition and decreasing its severity. This also generates a need for regular screening for dry eye in this group of people who carry an immense burden of dry eye and are probably underreported due to their ignorance toward health.

We found a prevalence of 67% dry eye among the diabetic patients. This is consistent with a study conducted by Manaviat et al. in Iran where 54.3% of the type 2 diabetic patients suffered from dry eye syndrome.[26] Possible reason for this may be the diabetic sensory or autonomic neuropathy or the occurrence of microvascular changes in the lacrimal gland.[27]

Two patients of the sample were soft contact lens users and both of them had dry eye. Both of these patients were regular contact users with >10 h of lens usage every day. It has been found previously that prelens tear film thinning time was most strongly associated with dry eye followed by nominal contact lens water content and refractive index. This, together with poor lens wettability, could be a basis for a higher evaporative loss during contact lens wear and was attributed to potential changes in tear film lipid composition.[28]

Seventy-two percent of the patients on topical antiglaucoma medications (6.3%) had dry eye. Many components of eye drop formulations can induce a toxic response from the ocular surface. The most common offenders are preservatives such as benzalkonium chloride, which causes surface epithelial cell damage and punctuate epithelial keratitis. This interferes with ocular surface wetting.[1] Thus, the use of preserved drops is an important cause of dry eye in glaucoma patients. Possible solutions to this problem would be shifting to nonpreserved antiglaucoma drugs or simultaneous prescription of preservative free lubricants in this group of patients.

We found the prevalence of dry eye to be as high as 95% in patients with blocked meibomian glands (10.3%). As defined by the international workshop on MGD, MGD is a chronic, diffuse abnormality of the meibomian glands, commonly characterized by terminal duct obstruction and/or qualitative/quantitative changes in the glandular secretion. This may result in alteration of the tear film, symptoms of eye irritation, clinically apparent inflammation, and ocular surface disease.[29] Another study has found MGD as the most common cause of evaporative dry eye.[30] Further, aging is associated with the development of MGD, which in turn leads to tear film instability and evaporative dry eye.

The prevalence of dry eye was found to be 60% among the smokers. Previous studies have also related an increased prevalence of dry eye among smokers.[31] The reason for this is not clearly known, but smoking is indeed a suggested risk factor,[19] which needs to be further verified and quantified.

Symptoms of burning sensation, dryness, and stickiness are the most prevalent among dry eye patients. There have been a few cases where the symptoms did not match our findings. Asymptomatic patients or patients with very few symptoms were found to have dry eyes. We found the prevalence of dry eye to be 24.1% in asymptomatic patients. Nichols et al.[32] have reported this problem too where there was a lack of correlation between signs and symptoms of dry eye. This probably varies with patients’ awareness and sensitivity toward the symptoms.

The main limitation of this study is the use of fluorescein stain for TBUT instead of noninvasive BUT. Fluorescein itself can sometimes be irritating and lead to reflex tearing. Another drawback is that our study is a hospital-based study at a Tertiary Care Center, which itself could increase the prevalence of any disease condition compared to that conducted in the community.

This study reflects a major burden of DED among the routine outpatients. Further, there is lack of data for the same in our region of practice. Although a similar study was conducted in the state of Rajasthan, it had a major drawback as its results were based purely on univariate analysis.[33] This accounts for the need to gather more data in this field to know the exact extent of DED in our country.

Thus, various contributing factors for dry eye are age, female gender, outdoor jobs, tobacco consumption, diabetes mellitus, meibomian gland disease, antiglaucoma medications and contact lens use. These results should give motivation toward building up a more systematic and targeted approach toward this issue as dry eye is not just a burden on ocular health, but it is great economic burden too. A survey reported that American consumers spend over 100 million dollars per year toward lubricating eye drops.[34] Le et al.[35] in a population-based cross-sectional study in China reported an adverse impact on the vision-related quality of life as well as an impairment on mental health in patients having various dry eye symptoms. A good history and clinical examination can help us to bring out this under-diagnosed condition and deal with this situation more aggressively. Further studies need to be undertaken to establish a universal diagnostic criterion, concrete etiologic association and options to deal with the same.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Mr. Ajay Phatak and Mrs. Jaishree Ganjiwale for their help in statistical analyses of the data.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.The definition and classification of dry eye disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DE Haas EB. The pathogenesis of keratoconjunctivitis SICCA. Ophthalmologica. 1964;147:1–18. doi: 10.1159/000304560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:405–12. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denoyer A, Rabut G, Baudouin C. Tear film aberration dynamics and vision-related quality of life in patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torkildsen G. The effects of lubricant eye drops on visual function as measured by the Inter-blink interval Visual Acuity Decay test. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:501–6. doi: 10.2147/opth.s6225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson TL, Situ P, Jones LW, Fonn D. Dry eye symptoms assessed by four questionnaires. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:692–9. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318181ae36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): Discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AJ, Lee J, Saw SM, Gazzard G, Koh D, Widjaja D, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with dry eye symptoms: A population based study in Indonesia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1347–51. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, Mertzanis P, Begley C, Barnes R, Chalmers R, et al. Development and validation of the impact of dry eye on everyday life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G, Rolando M, Irkeç M, Benítez del Castillo J, et al. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: A clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1168–76. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols KK, Mitchell GL, Zadnik K. The repeatability of clinical measurements of dry eye. Cornea. 2004;23:272–85. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200404000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Palakuru JR, Aquavella JV. Correlations among upper and lower tear menisci, noninvasive tear break-up time, and the Schirmer test. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: Report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:108–52. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SC, Sanabria O, Kell H, Garcia CG, Felix C, et al. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tear-film disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 1998;17:38–56. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillon M, Maïssa C. Tear film evaporation – effect of age and gender. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maïssa C, Guillon M. Tear film dynamics and lipid layer characteristics – effect of age and gender. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaumberg DA, Dana R, Buring JE, Sullivan DA. Prevalence of dry eye disease among US men: Estimates from the Physicians’ Health Studies. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:763–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Incidence of dry eye in an older population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:369–73. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The epidemiology of dry eye disease: Report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uchino M, Dogru M, Yagi Y, Goto E, Tomita M, Kon T, et al. The features of dry eye disease in a Japanese elderly population. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:797–802. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000232814.39651.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dry Eye Syndrome. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2003. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 03]. American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Available at: http://www.aao.org/ppp . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieckow J. 6th International Conference on the Tear Film & Ocular Surface: Basic science and clinical relevance (Florence, Italy, September 2010) Ocul Surf. 2011;9:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(11)70004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galor A, Feuer W, Lee DJ, Florez H, Carter D, Pouyeh B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye syndrome in a United States veterans affairs population. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:377–84.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han SB, Hyon JY, Woo SJ, Lee JJ, Kim TH, Kim KW. Prevalence of dry eye disease in an elderly Korean population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:633–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khurana AK, Choudhary R, Ahluwalia BK, Gupta S. Hospital epidemiology of dry eye. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1991;39:55–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manaviat MR, Rashidi M, Afkhami-Ardekani M, Shoja MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome and diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. BMC Ophthalmol. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiserman I, Kaiserman N, Nakar S, Vinker S. Dry eye in diabetic patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichols JJ, Sinnott LT. Tear film, contact lens, and patient-related factors associated with contact lens-related dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1319–28. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson JD, Shimazaki J, Benitez-del-Castillo JM, Craig JP, McCulley JP, Den S, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1930–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bron AJ, Tiffany JM. The contribution of Meibomian disease to dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2004;2:149–65. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein BE, Klein R. Lifestyle exposures and eye diseases in adults. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols KK, Nichols JJ, Mitchell GL. The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea. 2004;23:762–70. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000133997.07144.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahai A, Malik P. Dry eye: Prevalence and attributable risk factors in a hospital-based population. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:87–91. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.16170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemp MA. Epidemiology and classification of dry eyes. In: Sullivan DA, Dartt DA, Meneray MA, editors. Lacrimal Gland, Tear Film and Dry Eye Syndromes 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 791–803. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Q, Zhou X, Ge L, Wu L, Hong J, Xu J. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life in a non-clinic-based general population. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]