Abstract

Purpose:

To report a case series of ocular sarcoidosis manifesting as optic nerve head granuloma.

Design:

Observational case series.

Results:

Unilateral presentation in three females and a male. None of them had symptoms suggestive of systemic involvement. Fundus examination in all the patients showed hyperemic optic discs with peripapillary subretinal granuloma. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme was elevated in all patients. Chest radiograph was within normal limits in all patients. High resolution computed tomography of the chest showed features of sarcoidosis in two patients. All patients were treated with oral steroids. Immunosupressants were given in three patients, intravenous steroid, followed by oral steroids given in three patients. Improvement in visual acuity was noted in all four patients.

Conclusion:

Primary optic nerve involvement in sarcoidosis is rare. Isolated optic nerve sarcoidosis may exist without any systemic manifestations. Corticosteroids with immunosuppressants form the mainstay of therapy.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, ocular sarcoidosis, optic nerve head granuloma

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology. It is characterized histologically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas. Nearly one and a half centuries after its discovery much remains unknown about the etiology, pathogenesis and treatment of the disease. Evidence suggests that sarcoidosis occurs as the result of an imbalance in T-cell location and function, causing an exaggerated cellular immune response and an increased T-helper/inducer response.[1]

A Case-Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis study has given important data relating to the epidemiology of sarcoidosis.[2,3,4] The incidence of sarcoidosis varies across ethnic groups, with African Americans having the highest incidence of sarcoidosis. Women are more likely to have eye and neurologic involvement than men. Sarcoidosis varies in severity and distribution from single organ involvement and self-limiting disease to chronic multisystem inflammation and organ failure. The lungs are involved in 90% of patients.[5] Other organs frequently involved include the lymph nodes, skin, eyes, and the musculoskeletal, endocrine, and nervous systems.

Ophthalmic changes are the most common extrathoracic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Ocular involvement has been said to occur in 22% of cases.[6] Ocular manifestations vary enormously and include granulomatous or nongranulomatous anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, retinal periphlebitis, multifocal choroiditis, papillitis, optic nerve granuloma, or papilledema, lacrimal gland enlargement and dry eye and, rarely, orbital involvement or scleritis. Secondary glaucoma and cataract are common. Ocular involvement can occur at any time during the course of sarcoidosis and can even predate the disease.[7]

Neurologic involvement occurs in about 5–16% of cases.[8] Involvement of the optic nerve, chiasm and tract in neurosarcoidosis is said to be uncommon, involving 1–5% of cases of sarcoidosis.[8] Acute multisystem sarcoidosis is rarely a diagnostic challenge. However, limited sarcoidosis is well recognized, and there are a plethora of reports of single-organ involvement in the literature, in these cases, diagnosis is often difficult.[9]

Direct infiltration of the optic nerve by sarcoid granulomas is probably the rarest documented optic nerve manifestation of sarcoidosis. We report a series of four cases of optic nerve head granuloma as the primary manifestation of sarcoidosis.

Case 1

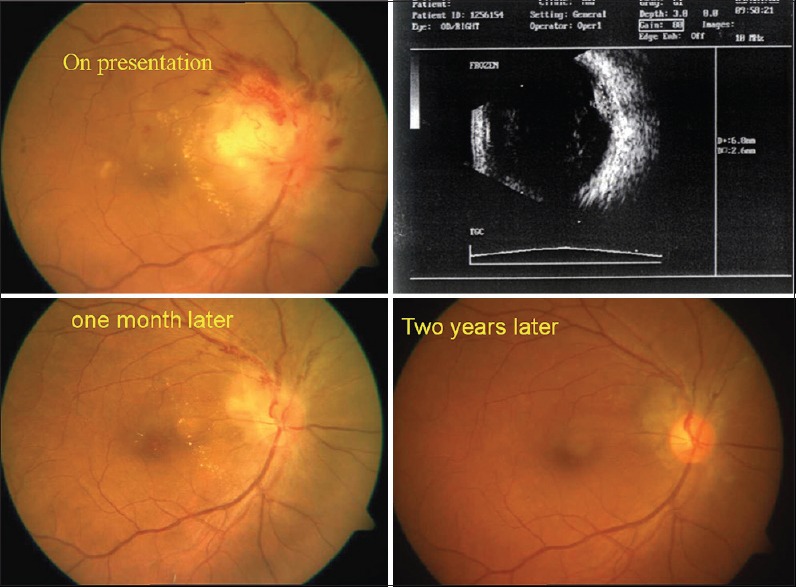

A 49-year-old female with no prior ocular complaints presented with a painless progressive decrease in vision in her right eye. The best corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/24, N18 and in the left eye was 6/6, N6. Slit lamp examination and intraocular pressure was within normal limits. Fundus examination revealed hyperemia and edema of the right optic nerve head. Flame shaped hemorrhages were seen radiating from the disc and there was presence of granuloma at the nerve head [Figure 1]. B-scan ultrasonography revealed mass lesion extending from optic nerve head to superotemporal peripapillary region with high surface reflectivity and low to moderate internal reflectivity which was suggestive of a granuloma. Chest X-ray was normal. High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of chest revealed hilar lymphadenopathy; however, patient had no systemic symptoms. Skin test for tuberculosis was negative. Laboratory studies revealed a normal blood count. The blood level of serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) was raised. The antibody assays for toxoplasmosis were negative. A diagnosis of sarcoid optic nerve granuloma was made and the patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g for 3 days. This was followed by a course of oral steroids 1 mg/kg body weight and methotrexate 15 mg/week. At 1-month follow-up, the best corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/9, N6 with a decrease in the disc edema [Figure 1]. The patient was maintained on minimum doses of oral steroids and methotrexate for a period of 2.5 years. During this period, she did not show any manifestations of systemic sarcoidosis. At final follow-up, 4 years after the first episode, the patient had a best corrected visual acuity of 6/6, N6 in the right eye with complete resolution of the optic nerve head granuloma [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph shows hyperemia and edema of the right optic nerve with hemorrhages with disc granuloma B-scan ultrasonography revealed mass lesion extending from optic nerve head to superotemporal peripapillary region with high surface reflectivity and low to moderate internal reflectivity which was suggestive of a granuloma

Case 2

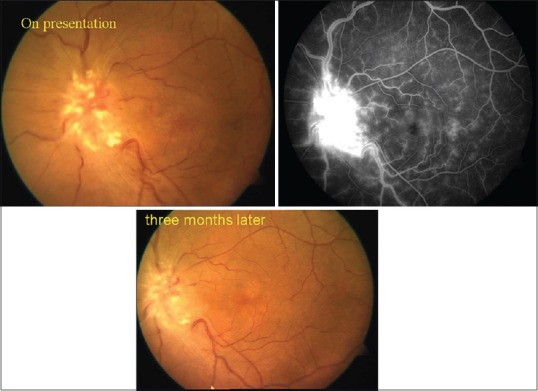

A 49-year-old female with no prior ocular complaints presented with a painless progressive decrease in vision in her left eye. The best corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/6, N6 and in the left eye was 6/24, N18. Slit lamp examination and intraocular pressure were within normal limits. Fundus examination revealed hyperemic, edematic left optic nerve head with surrounding engorged retinal veins [Figure 2]. Fluorescein angiography revealed optic nerve head hyperflourescence due to dye leakage consistent with disc edema. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated. Serum ACE level was elevated. Skin test for tuberculosis was negative. HRCT chest was suggestive of sarcoidosis though the patient did not have any systemic complaint. Therapy was started with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g for 3 days followed by a course of oral steroids 1 mg/kg body weight. At 3 months follow-up, the best corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 6/9, N8. The fundus picture also showed improvement in disc edema [Figure 2]. However, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Figure 2.

Fundus photograph shows revealed hyperemia and edema of left optic nerve head. Flourescein angiography shows optic nerve head hyperflourescence due to dye leakage consistent with disc edema

Case 3

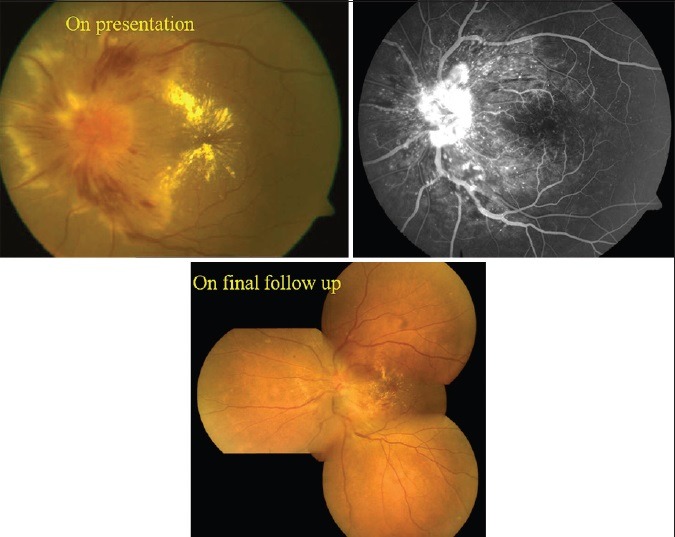

A 48-year-old female presented with a painless, progressive decrease in vision in her left eye and headache. The best corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/6, N6 and in the left eye was counting fingers at 1 m, <N36. Slit lamp examination and intraocular pressure were within normal limits. There was the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Fundus examination revealed hyperemic, oedematic left optic nerve head with exudates at the macula forming a macular star configuration. Fluorescein angiography showed disc hyperflourescence due to dye leakage consistent with disc edema and presence of blocked choroidal fluorescence due to exudates at macula [Figure 3]. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated. Serum ACE level was elevated. Skin test for tuberculosis was negative. HRCT and X-ray chest were within normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging brain revealed subcortical vasculitis in parietal and frontal region. Therapy was started with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g for 3 days followed by a course of oral steroids 1 mg/kg body weight and methotrexate 15 mg/week. In view of fluctuating blood glucose levels and the suspicion of a neurosarcoid, immunosuppressive agents were administered along with oral steroids. At 1-month follow-up, the best corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 6/9, N10 with resolving fundus lesions [Figure 3]. At 2 months follow-up, the best corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 6/7.5, N8. At final follow-up 5 months after presentation, her disc edema showed significant resolution and the best corrected visual acuity in her left eye was 6/9, N6.

Figure 3.

Fundus photograph shows hyperemic, edematic left optic nerve head with exudates at macula. Flourescein angiography showed disc hyperflourescence and blocked choroidal fluorescence due to exudates at macula

Case 4

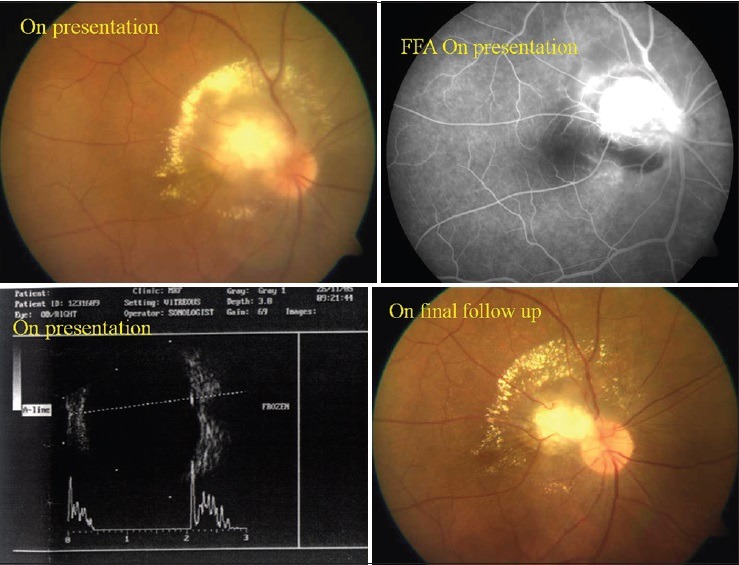

A 36-year-old male presented with a painless progressive decrease in vision in the right eye. The best corrected visual acuity in the right eye was 6/9, N6 and in the left eye was 6/6, N6. Slit lamp examination and intraocular pressure was within normal limits. There was presence of relative afferent pupillary defect in the right eye. Fundus examination revealed a granuloma at the right optic nerve head with presence of peripapillary subretinal fluid [Figure 4]. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated. Serum ACE level was elevated. Skin test for tuberculosis was negative. B-scan ultrasonography revealed mass lesion extending from optic nerve head to superotemporal peripapillary region with high surface reflectivity and low to moderate internal reflectivity which was suggestive of a granuloma. HRCT chest and X-ray chest were within normal limits. Therapy was started with oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg body weight along with methotrexate. At follow-up after 3 months, the granuloma had decreased in size [Figure 4] and the vision was maintained at the last follow-up after 7 months.

Figure 4.

Fundus photograph and B-scan ultrasonography shows a granuloma at the right optic nerve head with presence of peripapillary subretinal fluid

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause that commonly involves the eye and infrequently involves the central nervous system. Optic nerve involvement in sarcoidosis occurs in 1–5% of cases[8] and it is the second commonest nerve to be involved next to the seventh nerve. Optic nerve involvement in neurosarcoidosis may occur in a variety of forms[10,11,12] like papilledema, optic neuritis (retrobulbar neuritis or papillitis), optic atrophy or an optic nerve granuloma. Sarcoid granulomas can involve the optic nerve anywhere along its path up to optic chiasm.

Direct involvement of the optic nerve in sarcoidosis was first reported in 1964.[13] Later, cases of optic nerve sarcoidosis have been variously reported in the literature.[14,15,16] Optic nerve head sarcoidosis is frequently and erroneously labeled as a compressive or idiopathic optic neuropathy when supporting clinical signs go unrecognized and a directed diagnostic strategy is not used. When the optic nerve is involved in a patient with known sarcoidosis, the diagnosis is relatively straightforward. However, if optic nerve involvement is seen in the absence of known systemic sarcoidosis, it is imperative to establish the systemic diagnosis.

We had three females and one male in our series of four patients. The preponderance of females in our study is comparable to the female to male ratio of 8:3 reported by Beardsley et al.[15] They have studied 11 cases of optic nerve sarcoidosis which is the largest cohort of such cases studied so far. Our findings of female preponderance are also consistent with recent studies by Baughman et al.[17] and Menezo et al.[18] In our study, all patients had unilateral optic nerve involvement similar to that reported by Beardsley et al.[15] Bilateral involvement has also been reported previously.[19]

The use of elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme levels to aid the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is well established. The first laboratory test done in a suspected case of ocular sarcoidosis is serum ACE. Serum ACE was elevated in all four of our patients whereas it was elevated in 1 out of 3 patients tested (33.3%) in the study by Beardsley et al.[15] Frohman et al.[20] in a study of sarcoidosis of the anterior visual pathway have reported a raised serum ACE in 76% of cases.

The chest X-ray was normal in all our patients in contrast to abnormal chest X-ray reported in 72% by Beardsley et al.[15] and Frohman et al.[20] HRCT has been shown to be helpful in cases where chest radiography fails to provide diagnostic support. HRCT was suggestive of sarcoidosis in two of our patients (50%). In a study by Menezo et al.[18] chest radiography and HRCT showed signs compatible with sarcoidosis in 78% of patients with neurosarcoidosis.

Although optic nerve head involvement is often found in individuals with evidence of systemic sarcoidosis, it can be the initial and even the only sign of this disease. In our study, patients presented primarily with visual complaints without any systemic symptoms suggestive of sarcoidosis. On subsequent investigations, 3 of the 4 patients (75%) were found to have foci of systemic sarcoidosis in the form of pulmonary involvement and cerebral vasculitis. In a study by Beardsley et al.[15] nine out of 11 patients were found to have systemic involvement.

Treatment of sarcoidosis in general and neurosarcoidosis, in particular, may be extremely difficult.[21] Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy yet there are no standardized treatment protocols available as yet. The correct dose, the value of daily as opposed to alternate-day therapy, and the appropriate duration of therapy are unknown. All the four patients in our study received corticosteroids as the first line of treatment. Also, in view of the severity of involvement, intravenous high dose pulse steroid was given in two patients. Oral corticosteroids were given to all patient in the study by Beardsley et al.[15] Immunosupression with methotrexate was given in three patients in our study. Methotrexate has proven to be steroid sparing in a double-blind, randomized trial[22] of acute pulmonary sarcoidosis, and has proved effective in over 60% of patients treated with the drug for ocular manifestations.[23] Of the cytotoxic agents, it is the best supported drug for treatment of sarcoidosis.[24] All the patients in our study showed visual improvement in response to treatment.

In order to clear the diagnostic dilemma for ocular sarcoidosis, criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis were recently formulated.[25] Applying these criteria to our cases, the first and second case can be labeled as “presumed ocular sarcoidosis” with the presence of optic nerve head granuloma and a positive HRCT. The third and the fourth case may be labeled as “probable ocular sarcoidosis” with the positive findings of optic nerve head granuloma and an elevated serum ACE and a negative tuberculin skin test. Due to financial constraints, transbronchial biopsy was not done in any of our patients.

There are certain drawbacks to our study like it is a small series of four patients with limited follow-up and no tissue biopsy to conclusively establish the diagnosis.

Thus, sarcoidosis of the optic nerve should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with compressive or infiltrative optic neuropathies. Refined imaging modalities have facilitated the diagnosis when standard tests are negative. The ophthalmologist is the first to examine many patients with sarcoidosis. Prompt recognition of the disease and appropriate referral to a rheumatologist can aid in the efficient management of these patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Seamone CD, Nozik RA. Sarcoidosis and the eye. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1992;5:567–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, Rossman MD, Barnard J, Frederick M, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: Environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACCESS Research Group. Design of a case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS) J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1173–86. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semenzato G. ACCESS: A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2005;22:83–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gullapalli D, Phillips LH., 2nd Neurologic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Neurol Clin. 2002;20:59–83, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(03)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obenauf CD, Shaw HE, Sydnor CF, Klintworth GK. Sarcoidosis and its ophthalmic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:648–55. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(78)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley D, Baughman RP, Raymond L, Kaufman AH. Ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;23:543–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valeyre D, Chapelon-Abric C, Belin C, Dumas JL. Sarcoidosis of the central nervous system. Rev Med Interne. 1998;19:409–14. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(98)80865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ing EB, Garrity JA, Cross SA, Ebersold MJ. Sarcoid masquerading as optic nerve sheath meningioma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:38–43. doi: 10.4065/72.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley JS, Green WR. Sarcoidosis involving the optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:486–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1973.01000040488008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz JM, Bruno MK, Winterkorn JM, Nealon N. The pathogenesis and treatment of optic disc swelling in neurosarcoidosis: A unique therapeutic response to infliximab. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:426–30. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingestad R, Stigmar G. Sarcoidosis with ocular and hypothalamic-pituitary manifestations. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1971;49:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1971.tb08227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statton R, Blodi FC, Hanigan J. Sarcoidosis of the optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;71:834–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1964.00970010850011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papo I, Beltrami CA, Salvolini U, Caruselli G. Sarcoidosis simulating a glioma of the optic nerve. Surg Neurol. 1977;8:353–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beardsley TL, Brown SV, Sydnor CF, Grimson BS, Klintworth GK. Eleven cases of sarcoidosis of the optic nerve. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97:62–77. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan DR, Anderson RL, Nerad JA, Patrinely JR, Scrafford DB. Optic nerve involvement as the initial manifestation of sarcoidosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1988;23:232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, Rossman MD, Yeager H, Jr, Bresnitz EA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menezo V, Lobo A, Yeo TK, du Bois RM, Lightman S. Ocular features in neurosarcoidosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:170–8. doi: 10.1080/09273940802687812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jampol LM, Woodfin W, McLean EB. Optic nerve sarcoidosis. Report of a case. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972;87:355–60. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1972.01000020357023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frohman LP, Guirgis M, Turbin RE, Bielory L. Sarcoidosis of the anterior visual pathway: 24 new cases. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23:190–7. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gullapalli D, Phillips LH., 2nd Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4:441–7. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baughman RP, Winget DB, Lower EE. Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: Results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vucinic VM. What is the future of methotrexate in sarcoidosis? A study and review. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:470–6. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200209000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paramothayan S, Lasserson T, Walters EH. Immunosuppressive and cytotoxic therapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD003536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M. Members of Scientific Committee of First International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: Results of the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:160–9. doi: 10.1080/09273940902818861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]