Abstract

Objective

To determine the intermediate and long-term survival of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) and to determine factors that affect survival.

Method

Patients were identified from a prospectively maintained colonoscopy database. All patients who underwent colonoscopy during the period January 2008 to December 2012 and had histologically confirmed invasive carcinoma were included. These patients were contacted at the end of 2013 to determine their survival status. In addition to demographics, variables analyzed included presenting complaint and tumor site and stage at presentation.

Results

Of 1757 patients being subjected to colonoscopy, 118 had endoscopic and histologic documentation of invasive CRC. Of these the survival status of 102 was determined as of December 2013 and they formed the basis of our study. The mean age of the group was 62 years with approximately 20% of the group being age 50 years or younger. Females (54%) slightly outnumbered males. Anemia or overt rectal bleeding was a dominant indication (44%) and 65% of the tumours were left sided. There were 58 (57%) deaths and the median overall survival time was two years post diagnosis. Log rank tests for equality of survivorship looking at age, gender, tumor site and presentation revealed that only presenting complaint was a predictor of survivorship (p < 0.001). Patients presenting with bleeding or anemia have the best survival.

Conclusions

Long-term survival from colorectal cancer remains poor with only about 33% of patients being alive five years after their diagnosis.

Keywords: CRC survival, Jamaica, Poor outcome

Highlights

-

•

This manuscript documents the poor intermediate and long-term survival from colorectal cancer in Jamaica.

-

•

Mean survival was 24 months and only 33% of patients were alive five years after their diagnosis.

-

•

Patients presenting with anemia or bleeding had a better outcome.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has the third leading cancer incidence and mortality in males and females in Jamaica and the United States [1], [2]. Also well accepted is that one-third to a half of CRC patients will eventually die from their disease in high-incidence developed western countries [2], [3], [4]. This occurs even in the setting of organized screening programs, which although recommended, are absent from Jamaica and the Caribbean region [5]. It should also not surprise that the majority of our patients present with regional or distant metastasis [6]. A significant number of our patients also present emergently with complications thus requiring urgent surgical care. To complicate matters further adjuvant therapy is often not readily available [7]. It is therefore expected that CRC patients seen in our region will have a poorer outcome than their counterparts in the developed world.

Unfortunately there is a dearth of evidence regarding the long-term outcome for patients treated for CRC in the Caribbean region from the literature.

In order to determine the outcome of patients diagnosed with and treated for CRC, we recently followed up a cohort of patients with biopsy-confirmed CRC, all diagnosed electively at colonoscopy. This population set differs substantially from patients reviewed previously in local or regional publications because of the use of colonoscopy in establishing the diagnosis and the elective nature of their treatment. Hence to date this cohort of patients offers the best prospect for an outcome study for CRC in the region. The aim of this study therefore was to determine the intermediate and long-term survival of patients diagnosed with CRC and the factors that affected survival.

1.1. Patients and methods

During the period January 2008 to December 2012, 1757 patients underwent colonoscopy in a single institution performed by a single surgeon. Of these 120 patients had both endoscopic and histologic confirmation of invasive carcinoma of the colon or rectum and these patients formed the basis of this study. Data including date of colonoscopy, age, gender, patient's address and telephone contact, presenting complaint and tumor location was obtained from a prospectively maintained colonoscopy database. For the purpose of this study the right colon included the caecum, ascending and transverse colon up to just proximal of the splenic flexure and the left colon included the splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid and rectum. Histopathological diagnosis of invasive cancer on the biopsy specimen was made by an independent experienced gastrointestinal pathologist based at a separate tertiary institution and pathologic variables examined included tumour type and the degree of differentiation. Tumor stage was determined by reviewing the pathology reports of the resected specimens but where available pre-operative imaging and operative findings were also used.

Survival data was obtained by telephone interview of the patients or in the case of the deceased, their relatives. Where this was not possible the Registrar General Department which keeps records of all deaths in Jamaica, was contacted and the relevant information obtained. The interviews were conducted in December 2013, so that each patient would have a minimum of 12 months of follow-up and a maximum of 72 months. Complete time to event information, date of colonoscopy, date of death or live status at January, 1, 2014 was available for 102 of the 120 patients.

1.2. Statistical analysis

Survival time was defined as time from diagnosis to death, or retrieved from data obtained from the census for patients still alive at the end of the study period. Survival was analyzed using Log Rank tests and Kaplan–Meier survival curves for variables including gender, age (under 50 years vs 50 years or older) and stage of disease at diagnosis. Variables found to predict survival time (cancer stage and presenting complaints) were used to estimate hazard ratios in a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

2. Results

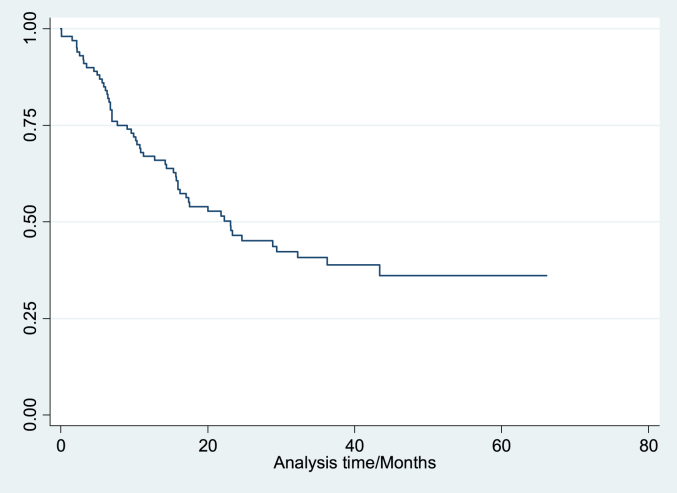

Data is summarized in Table 1a, Table 1b. The study group included 53 (54%) females and the mean age of the group was 62.5 years. Approximately 20% of patients were younger than age 50 years (Table 1a). Most (65%) tumors were located in the left colon and 44% of the patients presented with overt or occult bleeding. The median survival time was approximately two years post diagnosis (Fig. 1). There were 58 (57%) deaths up to the time of the interviews.

Table 1a.

Summary of patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| N | 102 |

| Age (years) | |

| Min | 23 |

| Median ± IQR | 63 ± 21 |

| Mean ± SD | 62.5 ± 14.9 |

| Max | 90 |

| Survival Time (months) | |

| Min | 0.07 |

| Median | 23.1 |

| Max | 66.14 |

Table 1b.

Summary of patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 46 |

| Female | 54 |

| Age | |

| 50 yrs or younger | 19 |

| Older than 50 yrs | 81 |

| Status (at January 1, 2014) | |

| Censored/Alive | 43 |

| Dead | 57 |

| Site of tumor | |

| Left colon | 65 |

| Right colon | 35 |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| 1 | 11 |

| 2 | 20 |

| 3 | 42 |

| 4 | 27 |

| Presentation/Complaint | |

| Anemia/Bleeding | 44 |

| Abdominal mass | 28 |

| Metastatic disease | 5 |

| Other | 23 |

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate for entire sample.

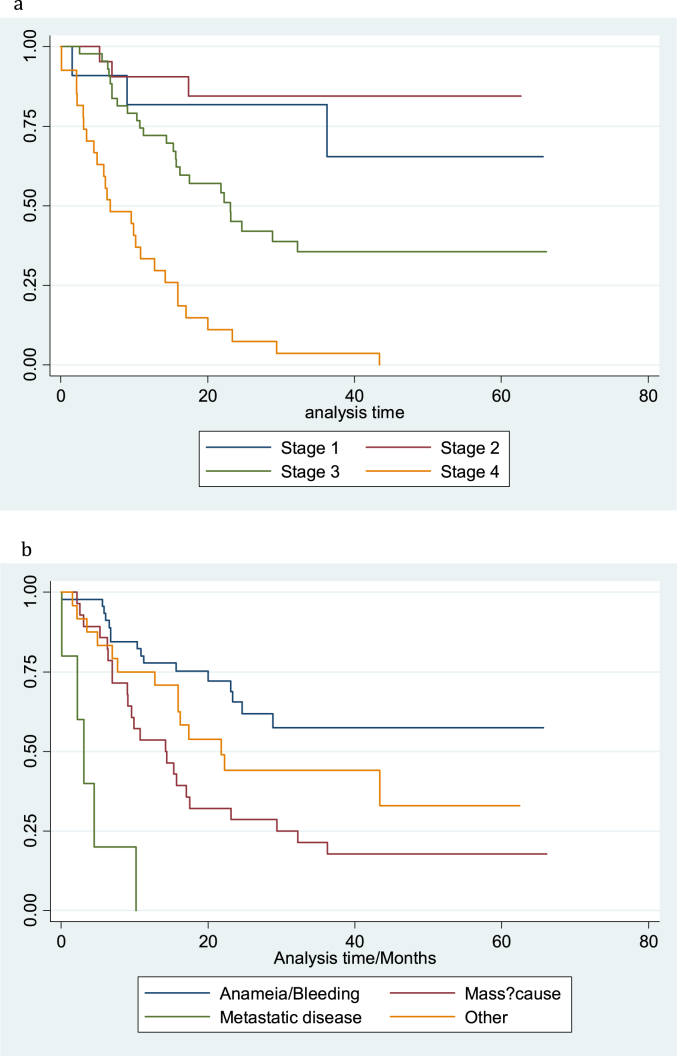

Log rank tests for equality of survival functions were conducted as well as a univariate Cox regression model. Significant predictors of survival were the stage of cancer at diagnosis and the patient's presenting complaint. A Cox regression model (Table 2), predicting survival indicated that persons who had a more advanced stage of cancer at diagnosis had worse survival. This model also showed that patients presenting with metastatic disease demonstrated an approximately six-fold greater risk of death when compared to persons who presented with anaemia or bleeding. Patients with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis had an almost five-fold increase in the risk of death when compared to patients who were seen with all other clinical presentations. After controlling for stage of disease at diagnosis, a comparison of survival of patients who presented with an abdominal mass and those who presented with metastatic disease did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.066). Estimated survival at five years for patients with stage 1, II and III disease was 80%, 65% and 33% respectively while bleeding or anemia was the only presenting complaint where 5-years survival exceeded 50% (Fig. 1, Fig. 2a,b).

Table 2.

Cox regression model predicting survival.

| Predicting survival time | Hazard ratio | Std. Err. | P | [95% Conf. Int.] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | 2.67 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 1.81 | 3.94 |

| Presentation complaint | |||||

| Anemia/Bleeding | 5.57 | 3.17 | 0.003 | 1.82 | 17.00 |

| Mass? Cause | 2.66 | 1.41 | 0.066 | 0.94 | 7.53 |

| Other | 4.58 | 2.59 | 0.007 | 1.52 | 13.84 |

Reference category for Presentation complaint is Metastatic disease.

Fig. 2.

a: Kaplan_Meier survival estimate for stage of cancer at diagnosis. b: Kaplan_Meier survival estimate for presenting complaint.

3. Discussion

Colorectal cancer is an important cancer in the region and one with an increasing incidence [1]. Given the estimated prevalence of the disease in our population, close to 500 new cases are diagnosed each year in Jamaica [1]. The mean age of 62 years in our study is a downward shift from cases seen during the last decade [6] where the mean age of CRC patients was 65.5 years. This correlates with a recent large report from the Jamaican population revealing mean age of 63 years at the time of their diagnosis for patients with CRC [8]. The finding that 20% of the overall group was less than age 50 years is important, further supporting the suggestion that the disease is occurring at an earlier age in our population. Patients under age 50 years would not yet qualify for screening and would be more likely to present with symptomatic disease, and with a poorer prognosis, a situation not dissimilar to the plight of blacks with CRC in the US. There is a recommendation that blacks commence screening for CRC at age 45 years [9] and this might also be relevant to our local population. Should other studies confirm the earlier onset of CRC in our population, the recommendation of a ‘one-off’ colonoscopy at age 60 [5] would have to be revised downwards, perhaps to age 55, if we are going to make a difference in CRC outcome for the average patient. While this will have the benefit of identifying and treating ‘polyp-formers’ before cancer development perhaps a better alternative is to emphasize more cost-effective methods of screening earlier. Feacal occult blood testing using immunochemical method comes readily to mind. Table 1b.

The majority of our patients' tumors are left-sided as was previously reported [6] and anemia and overt rectal bleeding were dominant symptoms. Anemia or bleeding per rectum was the presenting complaint for colonoscopy that had the best correlation with prognosis. It perhaps points to cultural differences where this finding is considered to reflect abnormal intestinal pathology that cannot be denied, hence it is more readily investigated, diagnosed and treated. This finding has been previously documented where the presence of rectal bleeding as a presenting complaint is positively associated with survival [10]. Other symptoms such as change in bowel habits or abdominal pain are perhaps more likely to be accommodated by the patients. Age, sex, and tumour site did not affect outcome. As expected tumour stage correlated directly with outcome.

The finding that 27% of the patients had Stage IV disease is in keeping with the 20–30% of cases of CRC in the developed world presenting with Stage IV disease. Five percent of patients with stage IV disease were diagnosed with hepatic metastasis and is in keeping with a report from West Africa where the pattern of metastasis is one of limited liver spread and more peritoneal metastasis [11] and may also contribute to our poor outcome as more that 80% of the Jamaican population are descendants from West Africa. Perhaps in the past, in the absence of colonoscopy these patients would have been diagnosed as malignancy of unknown primary that remains a relatively prevalent problem in our population [1]. It should be noted that none of these patients had surgery directed at treating the metastases. Patients presenting with metastasis were all dead by 14 months after diagnoses.

The combined total of patients presenting with Stages III and IV was nearly 70% and this directly accounted for the poor prognosis of these patients. This is in contrast with 40% presenting with stage 1 disease in the US (12). The health sector encounters significant challenges in providing adjuvant therapy to our patients [7] and it is likely that this further limits survival. The gross national income per capita income in Jamaica is estimated to be $US5220 [13]. While 5-flourouracil based regimens continue to be the mainstay of chemotherapy, given the high cost of some newer agents few patients can afford oxalaplatin or monoclonal antibody based chemotherapy, which is often included in regimens for patients with nodal or distant spread. It has been reported that 5-flourouracil based chemotherapy may not be as effective in Blacks and also reported to have greater toxicity [14]. Whilst the interpretation of data relating to the poorer outcome in blacks might be controversial [15], there is no doubt that a major contributing factor is access to adjuvant therapy. It has been demonstrated in studies in the US that when there is equal access to appropriate therapy racial disparities are no longer apparent [16].

The median life expectancy of patients in this study was two years after diagnosis and speaks to the number of patients at the time of their diagnosis with regional nodal or distant disease. This number exceeds the 60% a decade ago [6]. Factors that may have contributed to this finding include the lower socioeconomic status (SES) and the rural nature of the study population. While the SEC for the patients was not studied, there is support from the literature for the fact that rural populations of CRC patients generally have more advanced disease at the time of their diagnosis and a poorer survival [17], [18]. This is of great concern given that the study population was all electively diagnosed since generally when emergency cases are included in a cohort of CRC patients the reported prognosis is even worse [4].

This study has several limitations including the retrospective nature of the data collection and analysis and the possible bias from inaccurate staging and survival of patients. Also there was lack of information about SES, treatment and no standardization of post-treatment follow-up of the patients. All these factors are relevant to outcome. Approximately 20% of the qualified patients were lost to follow-up and not included in the long-term outcome. In addition the unique nature of the study population (being diagnosed at colonoscopy), albeit that all patients were histologically confirmed to have CRC, represents an ‘opportunity population’ for the authors rather that a standard CRC cohort in the Jamaican population. Still to our knowledge it is the first report of long-term outcome in a cohort of CRC patients from the Caribbean region. The finding of the Kaplan–Meier five-year survival data for the entire group of 30% is low in comparison to data on survival of patients managed currently with CRC. The 5-year survival is usually closer to 60–65% for this cancer in western countries [12], [19]. Health-care providers cannot have satisfaction when these figures are reviewed and comparing them with most western developed countries. Although we practice in a resource-restricted environment, this finding must generate robust debate regarding measures to improve the outcome of these patients if substantiated by other studies. Screening with immunochemical faecal occult blood testing, the judicious use of colonoscopy for diagnosis and the use a multi-disciplinary tumor board setting to formulate and implement a plan, after diagnosis including the timely use of adjuvant therapy where indicated are all relevant and have been shown to be effective in other populations. Therapy should also include surgical management of hepatic and pulmonary metastases where feasible. Efforts should be made to identify heritable CRC disease so that families can benefit from surveillance to identify cases early and offer appropriate post-cancer surveillance for optimal outcome. Increasing awareness of the disease and the benefits of screening by structured public health campaigns to educate both health care providers and the general population are also essential.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the UWI Faculty of Medical Science Ethics Committee Approval #: ECP 27, 2009/2010.

Funding

No funding was necessary for this study.

Author contribution

Study concept and design: JM Plummer, PA Leake, DI Mitchell.

Data Collection: D Ferron-Boothe, JM Plummer.

Data analysis and paper writing: JM Plummer, PO Roberts, ME McFarlane.

All authors contributed to and approve of the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to be declared with any of the authors and this work.

Guarantor

Dr Joseph M Plummer.

References

- 1.Gibson T.N., Blake G., Hanchard B. Age-Specific Incidence of Cancer in Kingston and St. Andrew, Jamaica, 1998-2002. West Indian Med. J. 2008;57:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R., Naishadham D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin B., Lieberman D.A., McFarland B. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008;58:130–160. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iversen L.H. Aspects of survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark. Dan. Med. J. 2012 Apr;59(4):B4428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee M.G. Colon cancer screening. West Indian Med. J. 2006;55:365. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McFarlane M.E.C., Rhoden A., Fletcher P.R., Carpenter R. Cancer of the colon and rectum in a Jamaican population. Diagnostic implications of the changing frequency and subsite distribution. West Indian Med. J. 2004;53:170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plummer J.M., Ward-Chin S., Roberts P.O. Radiotherapy for rectal cancer: towards an evidence-based approach suitable to the region. West Indian Med. J. 2013;62:649–650. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2012.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFarlane M.E.C., Plummer J.M., Leake P.A., Williams N.P., Ferron-Boothe D., Meeks-Aitken N. Colorectal cancer in Jamaica: patterns and anatomical distribution. West Indian Med. J. 2014;63(Suppl. 4):48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tammana V.S., Laiyemo A.O. Colorectal cancer disparities: issues, controversies and solutions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20(4):869–876. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Ishay O., Peled Z., Othman A., Brauner E., Kluger Y. Clinical presentation predicts the outcome of patients with colon cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2013 Apr 27;5(4):104–109. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i4.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saluja S., Alatise O.I., Adewale A., Misholy J., Chou J., Gonen M., Weiser M., Kingham T.P. A comparison of colorectal cancer in Nigerian and North American patients: is the cancer biology different? Surgery. 2014 Aug;156(2):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute-Surveillance Research Program. Cancer of the colon and rectum-SEER stat fact sheets. (accessed 19.09.15 at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html.

- 13.http://data.worldbank.org/country/Jamaica (accessed 25.01.15).

- 14.Dimou A., Syrigos K.N., Saif M.W. Disparities in colorectal cancer in African-Americans vs Whites: before and after diagnosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15(30):3734–3743. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yothers G., Sargent D.J., Wolmark N., Goldberg R.M., O'Connell M.J., Benedetti J.K., Saltz L.B., Dignam J.J., Blackstock A.W., ACCENT Colloborative Group Outcomes among black patients with stage 2 and 3 colon cancer receiving chemotherapy: an analysis of ACCENT adjuvant trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011;103(20):1498–1506. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill A.A., Enewold L., Zahm S.H., Shriver C.D., Stojadinovic A., McGlynn K.A., Zhu K. Colon cancer treatment: are there racial disparities in an equal –access healthcare system. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1059–1065. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald T.L., Lea C.S., Brinkley J., Zervos E.E. Colorectal cancer outcome inequalities: association between population density, race and socioeconomic status. Rural. Remote Health. 2014;14(3):2668. Epub 2014 Jul 22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh G.K., Williams S.D., Siahpush M., Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US cancer mortality: Part 1-all cancers and lung cancer and part 2-colorectal, prostate, breast and cervical cancers. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;2011:27. doi: 10.1155/2011/107497. Article ID 107497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minicozzi P., Kaleci S., Maffei S., Allemani C., Giacomin A., Caldarella A., Iachetta F. Disease presentation, treatment and survival for Italian Colorectal cancer patients: a EUROCARE high resolution study. Eur. J. Public Health. 2014 Feb;24(1):98–100. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]