Abstract

Background

The pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the deposition of cytoplasmic neuronal inclusions termed Lewy bodies. The major component of Lewy bodies is amyloid fibrils of α-synuclein. To investigate what causes α-synuclein aggregation is essential to understand its pathological roles in Parkinson’s disease. Various metal ions, including iron and copper, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Divalent metal ions can regulate α-synuclein fibrillation rate, however, few studies have been performed to investigate how trivalent metal ions interact with α-synuclein and their effect on α-synuclein fibrillation. The study of the interaction between divalent and trivalent metal ions with α-synuclein is of vital importance to realize the mechanism of α-synuclein fibrillation.

Results

Here we used nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to determine the trivalent metal ions (lanthanides) binding sites in α-synuclein. We found that lanthanide metal ions not only bind non-specifically to the C-terminal domain of α-synuclein, but also transiently interact with residues contain carboxyl groups in the N-terminal and NAC regions, the latter binding sites were not found for divalent cations. In addition, lanthanide ions bound α-synuclein exhibits slower conformational exchange rate. Compare to divalent cations, lanthanide ions accelerate α-synuclein fibrillation much faster.

Conclusions

We identified the lanthanide metal ions binding sites in α-synuclein and found a hierarchal effect for lanthanide ions binding to α-synuclein, driven by the interaction with aspartic acids and glutamic acids residues. Lanthanide ions binding also induced conformational dynamics change of α-synuclein. Compared to divalent cations, lanthanide metal ions significantly accelerated α-synuclein fibrillation, possibly due to the different inherent properties such as charge, binding sites and coordination modes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13628-016-0026-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: α-synuclein (αS), Lanthanide metal ions, Binding sites, Fibrillation

Background

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disease of the population over 65 [1]. The histological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the selective missing of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Intraneuronal deposits of fibrillar and misfolded proteins called the Lewy bodies appear in the affected brain areas. The main component of the Lewy bodies is α-synuclein (αS) aggregates [1–3]. Investigating what causes αS aggregation is important to understand its pathological roles in PD.

In aqueous solution, monomeric αS is a natively unfolded protein with no apparent ordered secondary structure detectable by Far-UV Circular Dichroism (CD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [4–6], but it forms β-sheet riched amyloid like fibrils under certain conditions [4, 7–9]. The N-terminal of αS exhibits a partially α-helical secondary structure upon binding with negatively phospholipid membranes and detergent micelles, while the C-terminus still remains dynamically unstructured [10–14]. αS has 140 amino acids with three distinct regions: the positively charged N-terminal region (residues 1–60); the hydrophobic NAC (non-amyloid β component) region (residues 61–95); and the highly negatively charged C-terminal region (residues 96–140) [15, 16]. The exposure of NAC region is considered as the main reason for αS fibrillation [16]. αS has the structural properties of auto-inhibition fibrillation due to the long-range transient intra-molecular interaction between the N-terminus and the C-terminus, which protecting NAC region from exposure [17–20].

Increasing evidences have shown that altered metal homeostasis might be involved in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. The possible involvement of heavy metals in the etiology of PD followed primarily from the results of epidemiological studies [21–24] and Lewy bodies component analysis in the parkinsonian substantia nigra [25, 26]. The potential link between metal ions and the PD related protein αS was observed in in vitro experiments. Recent studies show that the binding affinities of αS for diverse metal ions are different, but the binding sites are similar for the majority of metal ions. For divalent cations such as Fe2+, Mn2+, Co2+,Ni2+ and Ca2+, they all bound non-specifically to the C-terminal domain of αS [27–29]. But for Cu2+, it has high affinity to the αS N-terminus, and low affinity to the C-terminus [27, 30, 31]. No conformational change of αS was observed at low ionic concentration of various ions. At high concentration of metal ions, K+, Na+, Li+, Cs+, and Ca2+ has no effect on the unfolded structure of αS, but Mn2+, Cd2+, Mg2+ and Zn2+ induce a small increase in α-helix contents, and Cu2+, Co2+, Fe3+ and Al3+ induce more α-helix contents [32, 33].

Recently, studies have shown that lanthanide ions might affect the neuronal systems, but the toxicological behaviours were very complicated and the effects depended on a variety of factors [34–36]. With the increasing applications of lanthanides in industry, agriculture and medicine [37–41], particularly for the people who has long-term exposure in the electronics components industry or mining, public concern pays more and more attention on the toxicity of the lanthanides. In this study, we characterized the interaction between lanthanide metal ions (Ln3+) with recombinant human αS and the binding sites (region) were determined using NMR spectroscopy. We found that lanthanide metal ions accelerated αS fibrillation much faster than divalent cations in vitro. Based on the interaction information, we proposed the mechanism by which lanthanide metal ions accelerated αS fibrillation in vitro.

Results and discussion

Lanthanide metal ions binding sites determination

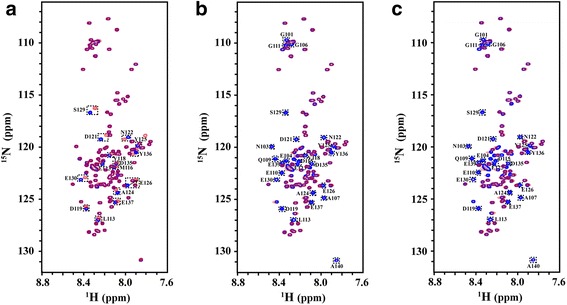

The 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) spectrum that contains one cross peak for each amide group (except proline) in a protein is routinely used to characterize protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions. The lanthanide metal ions (Ln3+) binding sites in αS were identified by using chemical shift perturbation of 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectroscopy of αS in the absence and presence of Ln3+ at various concentration ratios. We collected a series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of αS from 0 to 1/4 molar ratio of αS/Ln3+. Fig. 1 showed 1H-15N HSQC spectra of αS in the absence (blue) and presence (red) of Ln3+ at 1/1 molar ratio of αS/Ln3+, respectively. In the presence of diamagnetic Lu3+, the residues with significant chemical shift changes were labelled in Fig. 1a, and the assignments were according to Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB entry number is 16,543 for α-synuclein). In the presence of paramagnetic Tb3+ and Dy3+, the cross peaks of some residues became severely broadening and disappeared(Fig. 1b and c)due to paramagnetic relaxation enhancement effects, these residues were similar as those showing chemical shift changes in Fig. 1a. The 1H -15N spectra of αS in the presence of Ln3+ were also characteristic spectra of unfolded protein, suggesting that binding with Ln3+ might not cause significant structural change of αS.

Fig. 1.

1H-15N HSQC spectra of α-synuclein in the absence (blue) and presence of (red) (a) Lu3+, (b) Tb3+, (c) Dy3+ at molar ratios of αS/Ln3+(1/1), respectively. All spectra were obtained at 15 °C. Residues with chemical shift change or severely line broadening were labelled in the figure

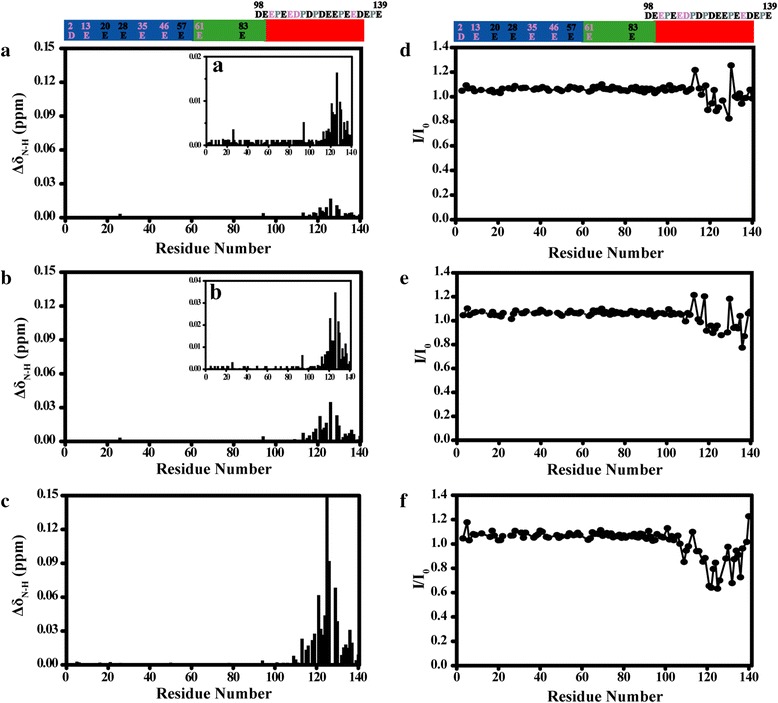

To map the binding sites of Lu3+ in αS, the chemical shift perturbations ΔδN-H induced by Lu3+ were plotted as a function of αS sequence. As shown in Fig. 2, significant chemical shift perturbations were located from residue 110 to 140 in the C-terminal region and residue Y125 with the largest chemical shift perturbation, whereas small or no change was observed for the residues in the N-terminal and NAC regions. With the molar ratio of αS/Ln3+ decreased from 4/1 to 1/1, the chemical shift perturbation of residues at the C-terminal region became larger, suggesting that Lu3+ binding with αS in the C-terminal region centered at residue Y125.

Fig. 2.

Chemical shifts and intensities changes of amide groups in αS at various concentration of Lu3+. The ΔδN-H of α-synuclein backbone amide groups were plotted as a function of residue number at molar ratios of αS/Lu3+ (a) 4/1, (b) 2/1, (c) 1/1, respectively. Inserts (a), (b) in (a) and (b) with smaller vertical scale. I/I0 profiles of α-synuclein backbone amide groups were plotted as a function of residue number at molar ratios of αS/Lu3+ (d) 4/1, (e) 2/1, (f) 1/1, respectively. αS has three distinct regions that were shown in different colour: the N-terminus (residues 1–60) is shown in blue; the hydrophobic NAC part (residues 61–95) is shown in green; and the C-terminus (residues 96–140) is shown in red. Asp, Glu residues in the C-terminus include D98, E104, E105, E110, E114, D115, D119, D121, E123, E126, E130, E131, D135, E137, E139, respectively, and Asp, Glu residues in the other regions were also marked in the figure. Pro residues marked in gray had no cross peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra. Residues highlighted in pink had no assignments in 1H-15N HSQC spectra

The intensity ratios of cross peaks in the presence (I) and absence of Lu3+ (I0) were also shown in Fig. 2d-f. When the molar ratio of Lu3+/αS decreased from 4/1 to 1/1, the signal intensity of residues located in the C-terminal region decreased, whereas small or no change was observed for the residues in the N-terminal and NAC regions. We also noticed that many cross peaks of C-terminal residues disappear when αS/Lu3+ ratio decreased further to 1/10 (Additional file 1: Figure S1), suggesting that binding with Lu3+ slows down αS conformational exchange rate.

In contrast to diamagnetic Lu3+, we did not observe residues with significant chemical shift change in the presence of the paramagnetic ions (Tb3+, Dy3+). By analysing the 1H-15N HSQC spectra, we found that some cross peaks showed significant intensity decrease and some cross peaks were even too broad to detect as a result of paramagnetic effects of Tb3+ and Dy3+. We plot the intensity ratios (I/I0) of cross peaks in the presence (I) and absence of Tb3+ (or Dy3+) (I0) as a function of αS sequence. As shown in Fig. 3, the intensity of C-terminal residues decreased much more than that of residues in the N-terminal and NAC region. A comparative analysis with Tb3+ and Dy3+ revealed a hierarchy in the binding of lanthanide ions to αS. According to the attenuation profile of cross peaks (I/I0), the whole residues of αS were divided into three parts: residues 1 to 97, residues 98 to 109, and residues 110 to 140. It is clear that the lanthanide ions bound preferentially to the region comprising residues 110–140, the secondary binding regions may contain residues 98–109, and the weak interaction binding regions contained residues in 1–97 regions, which were labelled with orange lines in Fig. 3. With the molar ratio of αS/Ln3+ decreased from 4/1 to 1/1, the I/I0 values of all the residues other than the residues in the C-terminal region decreased, while the I/I0 values of residues 3, 20, 21, 28, 57, 58, 59, 83, 84 decreased more than other residues in the N-terminal and NAC regions. We found these residues are aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues or residues near to aspartic acid and glutamic acid (Fig. 3). Interestingly, they are all negatively charged residues that have a carboxyl groups in the side-chain, which may have transient weak interactions with positively charged lanthanide ions. αS C-terminus contains many aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues and it was reasonable that lanthanide ions bound preferentially to this region.

Fig. 3.

Intensities changes of amide groups in αS at various concentration of Tb3+ or Dy3+. The I/I0 profiles of α-synuclein backbone amide groups were plotted as a function of residue number at molar ratios of (a) αS/Tb3+(4/1), (b) αS/ Tb3+(2/1), (c) αS/Tb3+(1/1), (d) αS/Dy3+(4/1), (e) αS/Dy3+(2/1), (f) αS/Dy3+ (1/1), respectively. The residues that were severely broadened were labelled in red rectangle. According to the attenuation degree of cross peaks (I/I0), the whole residues of αS were divided into three parts: residues 1 to 97, residues 98 to 109, and residues 110 to 140, which were all labelled with orange lines. αS sequence shown above the figure is the same as that in Fig. 2

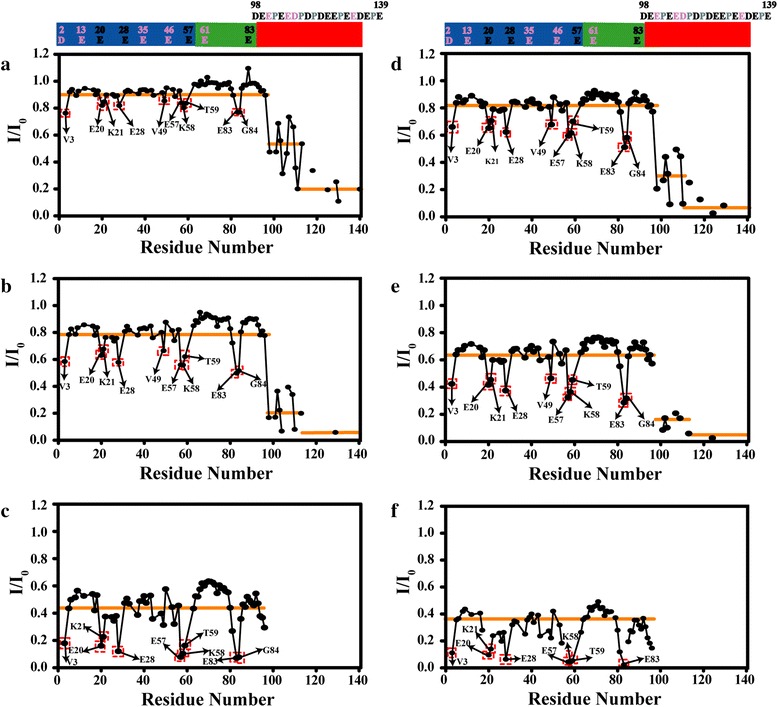

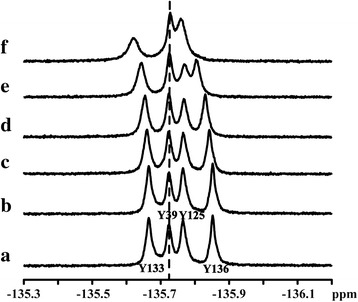

We also used 1D 1H spectra to obtain information on the roles of αS aromatic side chains in lanthanide binding. The 1H NMR spectra of αS in D2O (6.3-7.5 ppm) comprised the side chains of different aromatic residues: Phe (F4, F94), Tyr (Y39, Y125, Y133, Y136) (Additional file 1: Figure S2 and Figure S3), and the signals were assigned according to previous reports [27]. In the presence of low concentration lanthanide ions (Tb3+ and Dy3+), the Tyr signals intensity decrease significant, and with lanthanide ions (Tb3+ and Dy3+) concentration increasing, the Phe signals were further affected, suggesting lanthanide ions bound preferentially to C-terminus and might have transient weak interactions with N-terminal and NAC regions, consistent with 1H-15N HSQC spectra.

Many other metal ions and polyamines [42] also bind to the αS C-terminal region from residue 110 to 140. Other than the C-terminus, weaker binding sites involved residues 46–55 in the αS N-terminus was also reported for paramagnetic divalent cations such as Fe2+ and Co2+[27]. For Cu2+, the specific binding sites were identified as residues Met1, Asp2, and His50 in the N-terminus [27, 30]. It was worth mentioning that the binding sites of Ln3+ involved residues different from those binding with other divalent cations [27, 28, 30]. Residues containing a carboxyl groups in the N-terminal and NAC regions also have transient weak interaction with lanthanide ions. The binding character difference might be due to the inherent properties of different metal ions, such as charge, ionic radii and coordination abilities. The lanthanide metal ions, which possess ionic radii similar to Ca2+, are assumed to behave very similar to Ca2+ in protein binding. Through NMR titration experiment, we found that Ca2+ binding sites located in the αS C-terminus (Additional file 1: Figure S4 and Figure S5). The chemical shift perturbations of C-terminal residues are much smaller in the presence of Ca2+ than that of Lu3+, suggesting that αS-Ca2+ binding is relatively weak. The pattern of the chemical shift perturbation was also different from that induced by lanthanides ions. Our observations suggest that although lanthanides ions have similar ionic radii to Ca2+, they show different binding properties with αS. Diamagnetic metal ion Al3+ was also reported as an effective promoter to αS fibrillation, and we also studied Al3+ binding sites in αS (Additional file 1: Figure S6 and Figure S7). We found no obvious chemical shift perturbations were observed in the presence of Al3+, and only large intensity attenuation of cross peaks were located in the αS C-terminus, which suggested that binding with Al3+ slows down αS conformational exchange rate. Such conformational exchange was also observed in the presence of high concentration of Lu3+ (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Since the affinities for the Ln3+ with αS is similar, the different degree of broadening for Dy3+ and Tb3+ must be from slightly different paramagnetic properties: the total angular momentum quantum number J for Dy3+ is 15/2, which is a little larger than that for Tb3+ (J = 6), meanwhile the unpaired electron correlation time τe of Dy3+ is 0.3 × 10−12s, which is a little larger than that of Tb3+ (τe = 0.2 × 10−12s) [43]. These different properties may explain why the intensity ratios of cross peaks in the presence of Dy3+ decrease more severely than that in the presence of Tb3+. The strong paramagnetic properties of lanthanide ions might have solvent PRE effect, which makes the cross peaks intensity ratios of most observed residues in the N-terminal and NAC region decreased to 0.4 or 0.6 (Fig. 3c, f).

As for diamagnetic ion (Lu3+), significant chemical shift perturbations were not observed in the N-terminal and NAC regions. It may be due to the fact that PRE is more sensitive to local structural perturbation than chemical shift, because paramagnetic relaxation enhancement is proportional to r−6, where r is the distance between paramagnetic ion and nucleus observed.

To further confirm the binding sites, 19F NMR was also employed to study the αS - Lu3+ interaction. The 19F chemical shift is sensitive to the change of local chemical environment, hence it is a good reporter of binding sites. 3-19F tyrosine labelled αS were prepared and 1D 19F NMR spectra were recorded at different concentration ratios of Lu3+ (Fig. 4). The four 19F resonances (tyrosine 133, 39, 125, 136) were assigned according to previous research [44]. From Fig. 4, the 19F chemical shift of residue 39 in the N-terminus remained the same at different αS/Lu3+ ratios, however, chemical shift and shape of residues 125, 133, 136 in the C-terminal region changed during the titrations, indicating the binding is in the fast time scale and is weak as the titration is incomplete. The results suggested that the primary binding sites of Lu3+ located at C-terminal region, which was consistent with 1H-15N HSQC and 1D 1H experimental results. In a word, like many divalent metal ions such as Fe2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+ and Ca2+ [27, 28], lanthanide ions also bound non-specifically to the C-terminal domain of αS, and residues contain the carboxyl groups in the N-terminal and NAC regions that also have transient weak interaction with lanthanide ions, which was not reported in other studies of divalent metal ions interacting with αS.

Fig. 4.

1D 19F spectra of α-synuclein at different molar ratios of αS/Lu3+ (a) 1/0, (b) 4/1, (c) 2/1, (d)1/1, (e) 1/2, (f) 1/4

Lanthanide metal ions effects on αS conformation

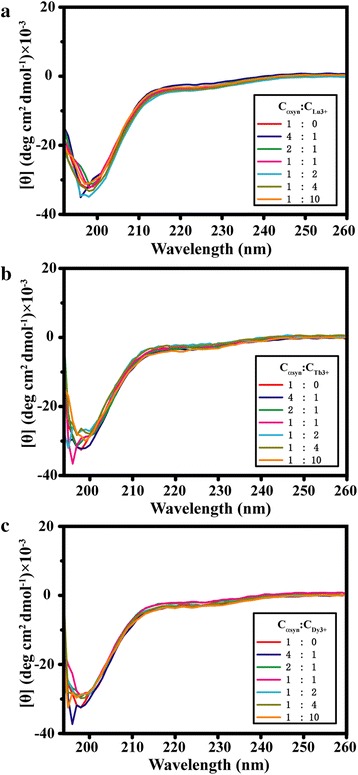

The narrow dispersion (7.8-8.3 ppm) of amide 1H chemical shift suggested that αS remained disordered in the presence of lanthanide metal ions. Besides NMR spectroscopy, far-UV circular dichroism (CD) was also used to monitor the conformational change in presence of lanthanide metal ions. In the absence of Ln3+, the spectra of αS exhibited substantially disordered structure (no characteristic α-helix or β-sheet peaks in the 210–230 nm or 198 nm regions). In the presence of different ionic ratios, even in the higher ionic ratios, the spectra were always indicative of essentially unfolded protein, suggesting that lanthanide metal ions binding could not cause significant structural change of αS (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Far-UV CD spectra of α-synuclein at different molar ratios of lanthanide metal ions, (a) αS/Lu3+, (b) αS/Tb3+, (c) αS/Dy3+, respectively

The hydrodynamic property of a macromolecule has been extensively used to study conformational changes accompanying molecular unfolding, association and aggregation. We employed 1H pulsed-field gradient NMR to investigate the hydrodynamic properties of the αS-Lu3+ complexes at different concentration ratios of αS/Lu3+. We measured the hydrodynamic radiuses of αS in the absence and presence of Lu3+. The radius of αS in the free state was approximately 31 Å, consistent with previous reports [27], and no large changes were observed at different αS/Lu3+ concentration ratios (Table 1). It suggested that binding with Lu3+ did not affect αS size, or cause any inter-molecular association.

Table 1.

The measured translational diffusion coefficients of dioxane and α-synuclein and the calculated hydrodynamic radius of α-synuclein at different concentration ratios of αS/Lu3+

| CαS : CLu3+ | Translational diffusion coefficients | Hydrodynamic radius RH (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| αS (methyl regoins from 0.87–0.56 ppm) D t × 10−11(m2/s) | Dioxane (3.65–3.53 ppm) D t × 10−10(m2/s) | ||

| 1 : 0 | 5.802 ± 0.001 | 8.482 ± 0.004 | 30.99 ± 0.05 |

| 4 : 1 | 5.949 ± 0.004 | 8.610 ± 0.004 | 30.68 ± 0.03 |

| 2 : 1 | 5.823 ± 0.006 | 8.488 ± 0.004 | 30.90 ± 0.04 |

| 1 : 1 | 5.845 ± 0.004 | 8.575 ± 0.004 | 31.10 ± 0.03 |

| 1 : 2 | 5.939 ± 0.003 | 8.626 ± 0.004 | 30.79 ± 0.02 |

| 1 : 4 | 5.915 ± 0.003 | 8.694 ± 0.005 | 31.16 ± 0.02 |

Lanthanide metal ions effects on αS fibrillation

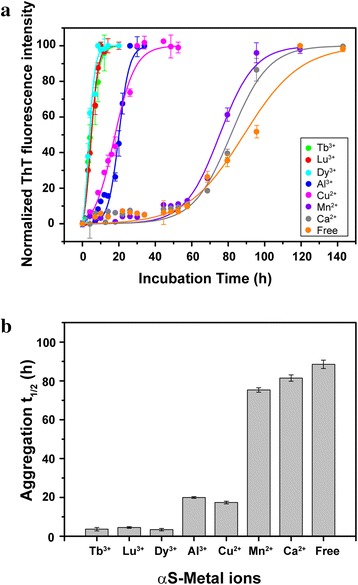

αS formed insoluble amyloid fibrils under some certain experimental conditions, and Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence was generally used to monitor its fibrillation [45–48]. We studied αS fibrillation rates at different concentration ratios of αS to lanthanide metal ions (Additional file 1: Figure S8). The results indicated that αS fibrillation was accelerated in the presence of Ln3+, and the accelerating effect of Ln3+ depend on its concentration, higher concentration resulted in faster fibrillation. Different lanthanide metal ions seemed to have similar effects on promoting αS fibrillation. Compared to cations such as Al3+, Cu2+ and Mn2+, lanthanide metal ions (Lu3+, Dy3+, Tb3+) induced αS fibrillation much faster (Fig. 6). Ca2+, which possess ionic radii similar to lanthanide ions, are assumed to behave very similar to lanthanide ions in αS fibrillation, but to our surprise, Ca2+ did not significantly accelerate αS fibrillation. This result suggests that αS fibrillation kinetics can be modulated by interactions.

Fig. 6.

a Comparison of αS fibrillation rate in the presence of different metal ions. 100 μM αS in the presence of 0 μM metal ions (orange), 400 μM Ca2+ (gray), Mn2+ (violet), Cu2+ (magenta), Al3+ (blue), Dy3+ (cyan), Lu3+ (red), Tb3+ (green), respectively. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to 100 units. The error bars in figure were standard deviations of three measurements. Points with no visible error bars represent measurements with tiny variance. Solid lines were the fits according to equation 1. b Lag time t1/2 values (hours) obtained for αS in the absence and presence of different metal ions: control (89 ± 2), Ca2+ (82 ± 2), Mn2+ (75 ± 1), Cu2+ (17 ± 1), Al3+ (20 ± 1), Dy3+ (4 ± 1), Lu3+ (5 ± 1), Tb3+ (4 ± 1). Error bars denote the fitting errors of experiments

Many metal ions can accelerate αS fibrillation. The reason is very complex, and many factors involved in it. The different effects on αS fibrillation rate might be due to the inherent properties of different metal ions, such as binding sites, coordination modes. Positively charged metal ions neutralizing negatively charged αS, and resulting in stronger intermolecular association is also regarded as a reason for αS faster aggregation. Besides binding with αS C-terminus, lanthanide metal ions show very novel coordination modes, and residues contain the carboxyl groups in αS N-terminal and NAC regions that also have transient weak interaction with lanthanide ions, which is not reported in other studies of divalent metal ions interacting with αS. This specific interaction can disturb αS local conformation, and may be another reason for αS faster fibrillation. We also notice that many cross peaks of C-terminal residues disappear when αS/Lu3+ ratio decreased further to 1/10, suggesting that the presence of Lu3+ reduces the αS conformation exchange rate. Such conformational exchange reduction is also observed in the presence of Al3+. Slow αS conformational exchange rates make the expose hydrophobic residues contact long enough to form associated oligomers, which is crucial for protein fibrillation. When the conformational exchange rate is fast or almost the same as the bimolecular encounter rate, there is not enough time for molecules association occurring.

Conclusions

In summary, we identified the lanthanide metal ions binding sites in αS by employing the chemical shift perturbations and paramagnetic effects of these metal ions. In particular, we found a hierarchal effect for lanthanide ions binding to αS, driven by the interaction with specific residues, namely, aspartic acids, glutamic acids residues. Compared to divalent cations, lanthanide metal ions significantly accelerated αS fibrillation, possibly due to their different inherent properties such as charge, binding sites and coordination modes. The study here also suggest that binding induced change of conformational exchange dynamics provide a possible molecular mechanism to understanding αS fibrillation.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Plasmids contained the coding sequence of α-synuclein were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) competent cells. Expression and purification of 15N-labeled wild-type or 19F-labeled (Y39F, Y125F, Y133F, Y136F) α-synuclein were performed as previously described [44, 49, 50].

Chemical Reagents

Thioflavin T (ThT), TbCl3•6H2O, DyCl3•6H2O and LuCl3•6H2O from Sigma or Alfa Aesar were used without further purification. All other chemicals were of analytical grade from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements

Samples containing 20 μM αS with different concentration of lanthanide metal ions in 10 mM MES and 100 mM NaCl at pH 6.0 were used for CD measurements. CD spectra were recorded on a ChirascanTM CD spectrometer in 10 mm cells from 260-190 nm with a step size of 1 nm and a bandwidth of 1 nm.

Fluorescence measurements

Samples comprised of 100 μM αS with 400 μM different metal ions in 10 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM phenylmethanesulfonyl (pH 6.0) were used for fibrillation experiments. αS fibril formation was induced at 37 °C by agitation with 220 rpm in the shaker. During fibrillation, small aliquots (10 μl) were removed and mixed with 1 mL 25 μM ThT. The fluorescence intensities were measured to monitor αS fibrillation. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded at 482 nm on a HORIBA Fluoromax-4 spectrometer.

The aggregation data was analysed using equation (1) [42], where α[t] denotes the values measured by ThT fluorescence experiments, k app is the apparent fibrillation rate constant, and t1/2 is the lag time to the transition midpoint in the process from monomer to aggregate.

| 1 |

NMR Spectroscopy and Data Analysis

NMR Buffer contained 10 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl (pH 6.0). Protein was concentrated to 0.25 mM in 90 % NMR Buffer and 10 % D2O. 1H-15N HSQC spectra and diffusion experiments were acquired on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryoprobe at 288 K. The HSQC spectra were acquired with sweep widths of 7212 Hz (1H) and 1581Hz (15N), 2048 × 256 complex points, 4 scans per t1 point, and a 1.5 s recycle delay. The spectral widths for the diffusion experiments were 9615Hz, with 32 K complex points, 56 scans, and a 1 s recycle delay. 1D 19F NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 19F/1H/13C/15N cryoprobe. Spectra were recorded with a 11.3 kHz sweep width, 350 scans, 16 K complex points and a recycle delay of 2 s. Proton decoupling was applied to all 1D 19F NMR spectra. Chemical shifts are referenced to trifluorotoluene at −63.72 ppm. For analysis of the chemical shift perturbations (ΔδN-H) of 1H and 15N backbone resonances in the HSQC spectra, a weighted average chemical shift change were calculated according to the equation (2) [51], where ΔδH and ΔδN denoted the chemical shift difference in the presence and in the absence of Ln3+ in the 1H dimension and 15N dimension, respectively.

| 2 |

For the 1H pulsed-field gradient NMR experiments, we used 1,4-dioxane as an internal radius standard (2.12 Å) and viscosity probe. Diffusion spectra were acquired using the stimulated echo experiment with 3-9-19 pulse module for water suppression (stebpgp1s19). 20 linearly spaced values of gradient strength were used in the range from 0.963 to 45.74 G/cm. The optimized diffusion (Δ) and gradient pulse times (δ) were 0.45 s and 3 ms, respectively. Decays rates had been extracted from the spectra for both the protein (Dprot) and the reference molecule (Dref), and the measured translational diffusion coefficients were showed in Table 1. The regions 0.87–0.56 ppm were used to calculate αS hydrodynamic radius (Rh) according to the equation (3) [52], where Rh prot was the protein hydrodynamic radius and Rh ref was the radius of the reference molecule. Spectra were processed and analysed by Topspin [53], NMRPipe [54], and Sparky [55].

| 3 |

Availability of supporting data

All the supporting data are included as Additional file 1.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China grant 2013CB910200 (C.L.), the 1000 Young Talents Program (C.L,), National Natural Sciences Foundation of China grant 21173258 (C.L.) and 21221064 (M.L.).

Abbreviations

- αS

α-synuclein

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- HSQC

Heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- CD

Circular Dichroism

- Ln3+

Lanthanide metal ions

- ThT

Thioflavin T

- MES

2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid

- Rh

Hydrodynamic radius

Additional file

Chemical shifts and intensities changes of amide groups in αS at various concentration of Lu3+. Figure S2. Tb3+ effects on 1D 1H spectra of αS aromatic side chains. Figure S3. Dy3+ effects on 1D 1H spectra of αS aromatic side chains. Figure S4. Ca2+ effects on αS 1H-15N-HSQC spectra. Figure S5. Chemical shifts and intensities changes of amide groups in αS at various concentration of Ca2+. Figure S6. Al3+ effects on αS 1H-15N-HSQC spectra. Figure S7. Intensities changes of amide groups in αS at various concentration of Al3+. Figure S8. Fibrillation of α-synuclein monitored by ThT fluorescence in the presence of different lanthanide metal ions. (DOC 1028 kb)

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13628-016-0026-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JB, ZZ, ML, CL. Performed the experiments: JB. Analyzed the data: JB, ZZ, ML, CL. Wrote the paper: JB, ZZ, ML, CL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jia Bai, Email: baijiasx@126.com.

Zeting Zhang, Email: zhangzeting@wipm.ac.cn.

Maili Liu, Email: ml.liu@wipm.ac.cn.

Conggang Li, Email: conggangli@wipm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(7):492–501. doi: 10.1038/35081564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forno LS. Neuropathology of Parkinson’s Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55(3):259–72. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. [alpha]-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839–40. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL. Evidence for a partially folded intermediate in alpha-synuclein fibril formation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(14):10737–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, Lansbury PT., Jr NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35(43):13709–15. doi: 10.1021/bi961799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bussell R, Jr, Eliezer D. Residual structure and dynamics in Parkinson’s disease-associated mutants of alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(49):45996–6003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink AL. The aggregation and fibrillation of α-synuclein. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39(9):628–34. doi: 10.1021/ar050073t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Necula M, Chirita CN, Kuret J. Rapid anionic micelle-mediated alpha-synuclein fibrillization in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):46674–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sprangers R, Kay LE. Quantitative dynamics and binding studies of the 20S proteasome by NMR. Nature. 2007;445(7128):618–22. doi: 10.1038/nature05512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliezer D, Kutluay E, Bussell R, Jr, Browne G. Conformational properties of α-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states1. J Mol Biol. 2001;307(4):1061–73. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulmer TS, Bax A. Comparison of structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human alpha-synuclein and Parkinson disease variants. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(52):43179–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgieva ER, Ramlall TF, Borbat PP, Freed JH, Eliezer D. Membrane-bound alpha-synuclein forms an extended helix: long-distance pulsed ESR measurements using vesicles, bicelles, and rodlike micelles. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(39):12856–7. doi: 10.1021/ja804517m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartels T, Ahlstrom LS, Leftin A, Kamp F, Haass C, Brown MF, et al. The N-terminus of the intrinsically disordered protein α-synuclein triggers membrane binding and helix folding. Biophys J. 2010;99(7):2116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lokappa SB, Suk JE, Balasubramanian A, Samanta S, Situ AJ, Ulmer TS. Sequence and membrane determinants of the random coil-helix transition of alpha-synuclein. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(10):2130–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uversky VN. Neuropathology, biochemistry, and biophysics of alpha-synuclein aggregation. J Neurochem. 2007;103(1):17–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho M-K, Nodet G, Kim H-Y, Jensen MR, Bernado P, Fernandez CO, et al. Structural characterization of α-synuclein in an aggregation prone state. Protein Sci. 2009;18(9):1840–6. doi: 10.1002/pro.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertoncini CW, Jung YS, Fernandez CO, Hoyer W, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, et al. Release of long-range tertiary interactions potentiates aggregation of natively unstructured alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(5):1430–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407146102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Tertiary contact formation in alpha-synuclein probed by electron transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(47):16388–9. doi: 10.1021/ja0561901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JC, Langen R, Hummel PA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Alpha-synuclein structures from fluorescence energy-transfer kinetics: implications for the role of the protein in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(47):16466–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407307101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dedmon MM, Lindorff-Larsen K, Christodoulou J, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. Mapping long-range interactions in alpha-synuclein using spin-label NMR and ensemble molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(2):476–7. doi: 10.1021/ja044834j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rybicki BA, Johnson CC, Uman J, Gorell JM. Parkinson’s disease mortality and the industrial use of heavy metals in Michigan. Mov Disord. 1993;8(1):87–92. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Kortsha GX, Brown GG, et al. Occupational exposures to metals as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48(3):650–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.48.3.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Kortsha GX, Brown GG, et al. Occupational exposure to manganese, copper, lead, iron, mercury and zinc and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(2–3):239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zayed J, Ducic S, Campanella G, Panisset JC, Andre P, Masson H, et al. Environmental factors in the etiology of Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1990;17(3):286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch EC, Brandel JP, Galle P, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y. Iron and aluminum increase in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an X-ray microanalysis. J Neurochem. 1991;56(2):446–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dexter DT, Carayon A, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y, Wells FR, Daniel SE, et al. Alterations in the levels of iron, ferritin and other trace metals in Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases affecting the basal ganglia. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 4):1953–75. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.4.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binolfi A, Rasia RM, Bertoncini CW, Ceolin M, Zweckstetter M, Griesinger C, et al. Interaction of alpha-synuclein with divalent metal ions reveals key differences: a link between structure, binding specificity and fibrillation enhancement. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(30):9893–901. doi: 10.1021/ja0618649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen MS, Vorum H, Lindersson E, Jensen PH. Ca2+ binding to alpha-synuclein regulates ligand binding and oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(25):22680–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe R, Pountney DL, Jensen PH, Gai WP, Voelcker NH. Calcium (II) selectively induces alpha-synuclein annular oligomers via interaction with the C-terminal domain. Protein Sci. 2004;13(12):3245–52. doi: 10.1110/ps.04879704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriarty GM, Minetti C, Remeta DP, Baum J. A Revised Picture of the Cu(II)-alpha-Synuclein Complex: The Role of N-Terminal Acetylation. Biochemistry. 2014;53(17):2815–7. doi: 10.1021/bi5003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasia RM, Bertoncini CW, Marsh D, Hoyer W, Cherny D, Zweckstetter M, et al. Structural characterization of copper(II) binding to α-synuclein: Insights into the bioinorganic chemistry of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(12):4294–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407881102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL. Metal-triggered structural transformations, aggregation, and fibrillation of human alpha-synuclein. A possible molecular NK between Parkinson’s disease and heavy metal exposure. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(47):44284–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JA, Brown DR. Alpha-synuclein and its role in metal binding: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(3):496–503. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng L, Xiao H, He X, Li Z, Li F, Liu N, et al. Long-term effects of lanthanum intake on the neurobehavioral development of the rat. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2006;28(1):119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu W, Xu S, Shao P, Zhang H, Wu D, Yang W, et al. Bioelectrical activity of the central nervous system among populations in a rare earth element area. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1997;57(1):71–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02803871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu A, Chakrabarty K, Haldar S, Addya S, Chatterjee GC. The effects of lanthanum chloride administration in newborn chicks on glutamate uptake and release by brain synaptosomes. Toxicol Lett. 1984;20(3):303–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(84)90164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobrynina N, Feofanova M, Gorelov I. Mixed lanthanide complexes in biology and medicine. J Inorg Biochem. 1997;67(1–4):168. doi: 10.1016/S0162-0134(97)80046-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang X, Li D, Peng A. Application of rare-earth elements in the agriculture of China and its environmental behavior in soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2002;9(2):143–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02987462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He ML, Wang YZ, Xu ZR, Chen ML, Rambeck WA. Effect of dietary rare earth elements on growth performance and blood parameters of rats. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2003;87(5–6):229–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0396.2003.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fricker SP. The therapeutic application of lanthanides. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(6):524–33. doi: 10.1039/b509608c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Li Y, Hao X, Zhang Q, Yang K, Li L, et al. Recent progress in therapeutic and diagnostic applications of lanthanides. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11(8):678–94. doi: 10.2174/138955711796268804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandez CO, Hoyer W, Zweckstetter M, Jares-Erijman EA, Subramaniam V, Griesinger C, et al. NMR of alpha-synuclein-polyamine complexes elucidates the mechanism and kinetics of induced aggregation. EMBO J. 2004;23(10):2039–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koehler J, Meiler J. Expanding the utility of NMR restraints with paramagnetic compounds: Background and practical aspects. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2011;59(4):360–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li C, Lutz EA, Slade KM, Ruf RA, Wang GF, Pielak GJ. 19 F NMR studies of alpha-synuclein conformation and fibrillation. Biochemistry. 2009;48(36):8578–84. doi: 10.1021/bi900872p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LeVine H., 3rd Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–84. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khurana R, Coleman C, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Carter SA, Krishna V, Grover RK, et al. Mechanism of thioflavin T binding to amyloid fibrils. J Struct Biol. 2005;151(3):229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krebs MR, Bromley EH, Donald AM. The binding of thioflavin-T to amyloid fibrils: localisation and implications. J Struct Biol. 2005;149(1):30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedersen JS, Dikov D, Flink JL, Hjuler HA, Christiansen G, Otzen DE. The changing face of glucagon fibrillation: structural polymorphism and conformational imprinting. J Mol Biol. 2006;355(3):501–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Ding TT, Williamson RE, Lansbury PT., Jr Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both alpha-synuclein mutations linked to early-onset Parkinson’s disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(2):571–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoyer W, Antony T, Cherny D, Heim G, Jovin TM, Subramaniam V. Dependence of α-synuclein aggregate morphology on solution conditions. J Mol Biol. 2002;322(2):383–93. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00775-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garrett DS, Seok YJ, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Identification by NMR of the binding surface for the histidine-containing phosphocarrier protein HPr on the N-terminal domain of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry. 1997;36(15):4393–8. doi: 10.1021/bi970221q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones J, Wilkins D, Smith L, Dobson C. Characterisation of protein unfolding by NMR diffusion measurements. J Biomol NMR. 1997;10(2):199–203. doi: 10.1023/A:1018304117895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rheinstetten G. TopSpin, version 2.1. Rheinstetten: Bruker BioSpin GmbH; 2007. p. Rheinstetten.

- 54.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6(3):277–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. San Francisco: University of California; 2007. [Google Scholar]