Abstract

Purpose

3′-Deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine ([18F]FLT) is being developed for imaging cellular proliferation. The goals were to explore the capacity of FLT-positron emission tomography (PET) to distinguish between recurrence and radionecrosis in gliomas and compare the results to those obtained with 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG).

Procedures

Fifteen patients with tumor recurrence and four with radionecrosis, determined by clinical course and magnetic resonance imaging results, were studied by dynamic [18F]FLT-PET with arterial blood sampling. A two-tissue compartment four-rate constant model was used to determine metabolic flux (KFLT), blood to tissue transport (K1), and phosphorylation (k3). FDG-PET scans were obtained 75–90 min postinjection.

Results

KFLT and k3, but not K1 or k3/k2+k3, reached significance for separating the recurrence from radionecrosis groups. Standardized uptake value and visual analyses of FLT or FDG images did not reach significance.

Conclusions

KFLT (flux) appears to distinguish recurrence from radionecrosis better than other parameters, FLT and FDG semiquantitative approaches, or visual analysis of images of either tracer.

Keywords: 3′-[18F]fluoro-3′-deoxythymidine, FLT, Fluorothymidine, Positron emission tomography (PET), Glioma, Radionecrosis, Proliferation imaging

Introduction

3′-Deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine, [18F]FLT, is a radio-labeled structural analog of the DNA constituent thymidine that is being developed as an imaging agent to assess cellular proliferation with positron emission tomography (PET). Although FLT is not incorporated into DNA, it is trapped in the cell due to phosphorylation by thymidine kinase-1, a cytosolic enzyme of the salvage pathway [1]. As such, it has the potential to image tumor proliferation in proportion to DNA synthesis via the salvage pathway. In the normal brain, FLT is not taken up because there is essentially no proliferative activity and little if any exchange across an intact blood-brain barrier. This gives FLT a distinct advantage for imaging tumors compared to 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose ([18F]FDG) as it should only be concentrated in proliferating tumor cells but not in normal brain. It may also allow for improved differentiation of radionecrosis from recurrence after therapy as well as shed light on the newly recognized problem of progression vs pseudoprogression in the immediate months following standard radiotherapy plus concurrent temozolomide chemotherapy [2, 3]. The intent of the present investigation was to explore preliminarily the capacity of [18F]FLT PET to distinguish radionecrosis in gliomas from recurrent disease and compare it to FDG.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Nineteen adult patients were included in the analysis (13 males, six females, age range 19, 67): four glioblastoma multiforme, two gliosarcoma, six anaplastic astrocytoma, three anaplastic oligodendroglioma, one anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, and three grade 2 oligodendroglioma (Table 1). Twelve of these patients were included in the safety evaluation of FLT [4], and six were included in a prior report [5]. All tumors were graded by the World Health Organization scheme. All were required to have a glioma and to have had previous radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Patients could not enroll in this study if there were clinically significant signs of uncal herniation, such as acute pupillary enlargement, rapidly developing motor changes (over hours), or rapidly decreasing level of consciousness. Female patients were required to be postmenopausal for a minimum of 1 year or be surgically sterile, or on a reliable method of birth control for a minimum of 1 month prior to the PET scans. Negative pregnancy test was required for reproductively capable women.

Table 1.

Age, pathology, treatments before and after FLT imaging, and survival

| Number | Age (sex) | Pathology (location) | Treatment prior to FLT-PET in chronological order | Time between RT and FLT-PET (months) | Time between last chemotherapy and FLT-PET | Course of MRI before FLT-PET | Course of MRI after FLT-PET | Treatment after FLT-PET | Survival after FLT-PET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 (M) | Oligo 2 (right temporal) | 59.4 Gy PCV TMZ Carboplatin Etoposide |

53 | 3 months | Stable to improved for 24 months | Slowly improved over 36 months | None | Alive 36 months |

| 2 | 54 (M) | GS (right frontal) | 70 Gy TMZ/cis-retinoic acid Carboplatin/thalidomide Rapamycin/gefitinib BCNU/irinotecan |

45 | 18 months | Stable for 30 months | Stable for 21 months | Hyperbaric oxygen | Alive 21 months |

| 3 | 47 (F) | AA (left frontal) | PCV 60 Gy TMZ Intraventricular MTX BCNU/irinotecan Etoposide Irinotecan |

44 | 1 month | Stable for 20 months | Stable for 21 months | None | Alive 21 months |

| 4 | 36 (M) | AO (right temporal) | 6,120 Gy + TMZ 22 Gy gamma knife TMZ 20 Gy gamma knife |

28 23 9.5 |

1 month | Stable to improved for 6 months | Improved over 18 months | TMZ | Alive 18 months |

| 5 | 62 (M) | GBM (left temporal) | Surgery + BCNU wafers 59.4 Gy TMZ 20 Gy gamma knife Carboplatin Gefitinib/etoposide 6TG/PCB/CCNU/HU |

24 | 4 months | Progression over 6 months | Progression over 6 months documented | HU/imatinib mesylate | 9.5 months |

| 6 | 47 (M) | Oligo 2 (right frontal) | 59.4 Gy PCV 1-125 seeds 12-15 Gy Brachytherapy 14 Gy TMZ |

107 54 24 |

2 months | Progression over 3 months | Progression documented for 5 months | TMZ | 6 months |

| 7 | 54 (M) | GBM (left thalamus) | 62 Gy + TMZ/celecoxib | 4.5 | 1 month | Progression over 3 months | Progression documented over 3 months | Bevacizumab/irinotecan | 4 months |

| 8 | 50 (M) | AA (right frontal) | 59.4 Gy PCV |

116 | 96 months | Progression over 6 months | Progression documented over 4 months | TMZ | 5 months |

| 9 | 37 (F) | AA (right frontal) | 59.4 Gy PCV |

120 | 108 months | Progression over 6 months | Progression documented over 11 months | TMZ Carboplatin Etoposide Cytoxan HU |

14 months |

| 10 | 40 (M) | AA (left frontal) | 59.4 Gy + TMZ | 8.5 | 2 months | Progression over 3 months | Overall progression interrupted by brief stabilization over 16 months | BCNU/irinotecan/erlotinib Bevacizumab/irinotecan/erlotinib Carboplatin Etoposide |

16 months |

| 11 | 62 (M) | AO (right temporal) | 55.8 Gy + TMZ | 9 | 1 month | Progression over 1 month | Progression over 2 months | TMZ | 3 months |

| 12 | 50 (M) | Oligo 2 (left parietal) | 59.4 Gy | 98.5 | No prior chemotherapy | Progression over 14 months | Progressive improvement (response) over 14 months in response to TMZ | TMZ | Alive 17 months |

| 13 | 67 (M) | GS (right frontal and temporal) | 63 Gy | 2 | None | Progression over 4 months | Progression over 6 months despite I-131-TM601 | Resection + I-131-TM601 | 7 months |

| 14 | 44 (F) | AA (left parietal) | 59.4 Gy | 29 | None | Progression over 7 months | Unknown | Unknown | 7 months |

| 15 | 45 (M) | GM (right temporal) | 59.4 Gy + TMZ 18 Gy radiosurgery |

15 14 |

1.5 months | Progression over 1 month | Resection complicated by infarction, no recurrence by MRI for 52 months | Resection with gliadel wafers Pathology showed recurrence |

Alive 56 months |

| 16 | 24 (F) | Anaplastic PXA (left temporal) | 54 Gy I-125 seeds 12–15 Gy TMZ Carboplatin |

34 30 |

1 month | Progression over 2 months | Stable after radiosurgery and additional chemotherapy but complicated by intratumoral hematoma | 17 Gy radiosurgery 6TG/PCB/CCNU/HU/FU Etoposide |

Alive 49 months |

| 17 | 41 (F) | GM (right frontal) | 60.4 Gy + TMZ TMZ 18 Gy radiosurgery CDDP/BCNU |

12 3 |

2 months | Progression over 2 months | Progression over 3 months | cis-retinoic acid/etoposide | 6 months |

| 18 | 19 (F) | AO (pineal) | 59.4 Gy 20 Gy radiosurgery TMZ |

16 12 |

2 months | Progression over 1 month | Progression over 1.5 months | None | 3 months |

| 19 | 34 (M) | AA (right frontal) | 61.2 Gy TMZ |

11 | 6 months | Progression over 6 months | Stable on chemotherapy for 21 months | TMZ | Alive 23 months |

Numbers 1–4 are radionecrosis cases; numbers 5–19 are recurrences

HU hydroxyurea, TMZ temozolomide, BCNU carmustine, CCNU lomustine, PCB procarbazine, PCV procarbazine/lomustine/vincristine, 6TG 6-thioguanine, MTX methotrexate

Patients were tested for hematologic, liver, and renal function prior to and after the FLT scans [4]. All patients were also required to undergo a physical and complete neurological examination before and after the FLT scans.

Each patient had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a 1.5-T device without and with contrast enhancement within 14 days of FLT-PET imaging. All patients except two had a FDG-PET scan within 4 days of their FLT-PET scan; one had none and for another, the interval was 25 days.

Patients 1 through 4 were judged to have radionecrosis because serial MRI studies and clinical examinations preceding and following the PET scans from 16 to 31 months were stable or improved (Table 1). Ten patients were deemed to be recurrence due to subsequent progression to death within 3 to 16 months accompanied by both clinical deterioration and MRI worsening. In four patients, still living, recurrence was similarly determined by progressively worsening clinical and MRI findings. Surgical resection proved recurrence in patient 15.

The placement of cases into either the radionecrosis or recurrence categories assumed that monitoring changes in clinical findings and MRI examinations, or lack thereof, through the course of the disease allowed this distinction to be made. In this and other publications, radionecrosis was diagnosed when there was no worsening of clinical and MRI examinations over months to years in the absence of any further treatment interventions [6–13]. Recurrence was diagnosed when clinical deterioration progressed along with worsening MRI findings ending in death. It is important to emphasize that the clinical and MRI findings both before and after the FLT studies were used for determining the categories. The separation into categories was not based on the FLT-PET results.

These studies were conducted under an investigational new drug (IND) for [18F]FLT held by the Cancer Imaging Program of the National Cancer Institute. The studies were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Committee, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center IRB, and the University of Washington Radiation Safety Committee. Each patient signed informed consent.

FLT Synthesis

3′-Deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine was synthesized as reported previously [4, 14]. Its radiochemical purity was >98% and the specific activity was such that patients received injection with not more than 1 μg carrier FLT, although the IND allows injections as high as 6.1 μg.

FDG Synthesis

2-[18F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose was synthesized by the method of Hamacher et al. [15] using the Nuclear Interface FX box technology. The radiochemical and chemical purity of the product was assayed by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and thin layer chromatography and was consistently >99% by both assays. The measured specific activity of the FDG was >740 MBq/mmol at end of synthesis.

MRI Imaging Protocol

Standard brain MR imaging was performed with a 1.5-T Signa (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) whole-body scanner with a standard head coil. The protocol for all subjects included a T1-weighted sequence acquired in the transverse imaging plane before and after administration of intravenous gadolinium (Gd). Axial T2, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and coronal T1 plus Gd sequences were included. All images were obtained at 5-mm section thickness with no gap. MRI images were coregistered to sum PET images with a method based on mutual information criteria [16].

FLT Imaging Protocol

This followed exactly the procedure reported previously [4, 5]. Briefly, [18F]FLT doses were calculated based on patient weight (2.7 MBq/kg, 0.07 mCi/kg) with a maximum dose of 185 MBq (5 mCi). [18F]FLT was administered i.v. over 1 min using an infusion pump. Dynamic PET acquisition was carried out for 90–120 min. A radial artery line was inserted to sample arterial blood for determination of radioactivity and plasma metabolite analysis. Arterial samples were obtained at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65, 70, 75, 80, 85, and 90±120 min using an automated blood sampler [17]. Three patients had hand-drawn arterial samples at the following time points: 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 min.

For each arterial blood sample, 0.2 mL plasma was assayed for radioactivity using a COBRA gamma counter (Packard Corp, Meriden, CT, USA). Since FLT has negligible serum protein binding [18], all of the activity associated with [18F]FLT in blood was assumed to be available for tissue uptake. An aliquot (0.4 mL) of the plasma from eight arterial samples (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min) was assayed for the relative amount of FLT and FLT-glucuronide as previously described [19]. The fraction of total activity present as [18F]FLT in each blood sample was fitted to a mono-exponential curve to provide a continuous function describing the fraction of the total plasma activity associated with [18F] FLT vs metabolites [19].

The PET studies were performed on a GE Advance PET tomograph (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) providing 35 image planes over a 15-cm axial field of view with a 4.25-mm slice spacing [20]. Images were acquired in 3D mode with the following dynamic sequence: 10×10, 4×20, 3×40 s, 3×1, 5×2, 4×3, and 12×5 or 18×5 min time frames for a total duration of 90 or 120 min. After correction for scatter and random coincidences, images were reconstructed by the method of 3D reprojection using 4.5 mm radial and 6 mm axial smoothing filters (Hanning) resulting in approximately isotropic image resolution of about 6 mm [21].

FLT PET Image Analysis

Regions of interest (ROIs) for tumor, brain, gray matter, and white matter were constructed on coregistered MRI T1+Gd or T2 images and transferred to FLT images summed between 30 and 60 min, an interval when transport of the radiotracer from blood to tissue is predominantly unidirectional. Tumor regions were placed on all of the planes containing portions of the lesion as indicated from the coregistered MRI T1+Gd or T2 images. The tumor ROIs were further constricted in size to include regions perimeterized by 50% of the maximum pixel of the entire tumor volume from the FLT summed image set. The ROIs from contiguous slices were combined to create volumes of interest (VOI) for each tissue type by means of Alice™ image processing software (HIPG, Boulder, CO, USA). VOIs were applied to the dynamic image set for data extraction.

Qualitative (visual) assessment of level of uptake in brain tumor and normal brain was performed by two experienced independent nuclear medicine specialists from viewing the 15–60-and 60–90-min uptake images and MR images. The coregistered MRI scans were available to the readers as they examined the FLT and FDG scans. The [18F]FLT-PET studies were interpreted as to confidence of tumor recurrence: 5=definite recurrence, 4=possibly, 3=equivocal, 2=probably necrosis, and 1=definite radiation necrosis. Visual assessment of FLT images preceded visual reading of FDG scans detailed below.

Semiquantitative assessment of [18F]FLT uptake was performed by calculating the standardized uptake value (SUV) and SUVmax on the 15–60- and 60–90-min image sets using standard SUV methodology corrected for decay. The SUVmax was obtained for the maximum pixel value within the tumor ROI. [18F]FLT tumor uptake was normalized for body surface area (BSA). The tumor radiotracer concentration C(T) (MBq/L) was determined from the PET image:

SUVbsa=C(T)/injected dose/BSA where BSA=weight (0.425)×height (0.725)×0.00718. Ratios of the SUV or SUVmax of tumor to that of cortex (T/C) or that of white matter (T/WM) were calculated.

Additionally, model-independent estimates of FLT uptake were assessed by a modified graphical analysis (GA) approach which corrects for blood metabolites [22]. The GA determination of flux may be valid for a short interval following injection, when the assumption of unidirectional transfer of FLT from blood to tissue is applicable [23]. Due to restricted transport of FLT, tissue pools of precursor require a greater time to stabilize with respect to blood delivery. Therefore, 30 and 60 min were chosen as the time boundaries for the linear fit in GA after examination of linearity in the contrast enhancing tumor regions. This method assumes that phosphorylated FLT nucleotides are completely retained in the tissue, an assumption that has yet to be validated in vivo and is not supported by cell culture experiments [1].

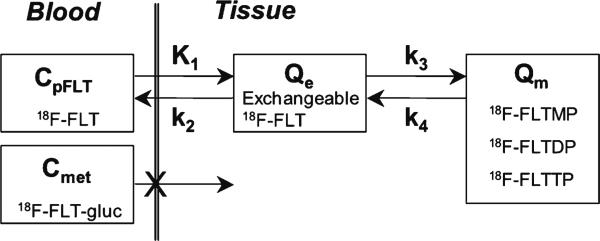

For quantitative analysis of FLT imaging data, we applied the kinetic model reported previously (Fig. 1) [5]. The transfer from blood into tissue across the BBB is represented by K1, while the return of nonphosphorylated FLT from a tissue compartment back to blood is represented by k2. The metabolic trapping of FLT through phosphorylation to produce FLT nucleotides is represented by k3, which is the rate limiting step for the retention of FLT in tissue. The nucleotides of FLT can leave the imaging region either by dephosphorylation back to FLT or through nucleotide transporters [1, 24]. The loss of image signal through these processes is described by k4.

Fig. 1.

The kinetic model of FLT metabolism is comprised of an exchangeable tissue compartment (Qe) and a compartment of trapped FLT nucleotides (Qm). Four rate constants (K1–k4) describe the kinetic transfer rates between the two compartments and blood. FLTMP FLT-monophosphate, FLTDP FLT-diphosphate, FLTTP FLT-triphosphate, FLT-gluc FLT-glucuronide synthesized in the liver, CpFLT concentration of FLT in arterial plasma, Cmet concentration of metabolites in arterial plasma.

FLT flux, KFLT, was estimated by compartmental modeling using parameters derived from fitting the FLT input function and the total blood activity curve to the tissue time–activity curve (TAC) data. The FLT flux constant is determined by the product of the rates of FLT using the following formula [19]:

| (1) |

where Vd is the early distribution volume for the reversible compartment, given by K1/k2, similar to prior reports [19, 25]. The key parameters for describing FLT uptake in tissue are the flux constant, KFLT, and the FLT blood–tissue transport rate, K1.

The regional VOI activity curves, the metabolite-corrected arterial input curve, and the total arterial activity curve were fitted to the FLT compartmental model using the weighted Levenberg–Marquart least squares minimization algorithm as implemented in a software package designed for PET data analysis (PMOD v2.85, PMOD group, Zurich, Switzerland). In the model optimization process, the residuals were weighted by the inverse variance of the total count rate in each frame of data, based on the standard deviation of the total uncorrected counts and the duration of the time frame [26]. Model parameters were estimated by minimizing the weighted residual sum of the square error between the model solution and the PET measurement.

Parametric image maps of each of the parameters were generated by mixture analysis [26–28] with the same dynamic image data, blood input functions, and two-tissue compartmental model used for the tissue TAC analysis. The tissue VOIs used to generate tissue TACs constructed on PET and MRI images were applied to the parametric image maps to determine the extent of FLT flux relative to Gd enhancement on MRI images. They were also used to determine the precision and bias of the parametric image values relative to modeling analysis of tissue TACs by means of the same imaging data and compartmental model.

FDG Imaging Protocol

[18F]FDG was injected i.v. (3.7 MBq/kg or 0.1 mCi/kg) with patients in a fasting state. Patients returned 45 min postinjection and were positioned in the tomograph in a dimly lit room. A transmission scan was obtained for 25 min followed by a 5-min 2D emission scan to correct the transmission data for patient radioactivity. A 15-min 3D emission scan was then acquired 75 min after the FDG injection. The attenuation-corrected 3D emission scan was reconstructed in transverse sections for interpretation.

FDG Image Analysis

Qualitative (visual) assessment of level of uptake in brain tumor and normal brain was performed by two independent nuclear medicine specialists from the 75–90-min uptake images and MR images. The [18F]FDG-PET studies were interpreted as to confidence of tumor recurrence: 5=definite recurrence, 4=possibly, 3=equivocal, 2=probably necrosis, and 1=definite radiation necrosis.

Semiquantitative assessment of [18F]FDG uptake was performed as described above by calculating the SUV and SUVmax on the 75–90-min image sets using standard SUV methodology corrected for decay. The SUVmax was obtained for the maximum pixel value within the tumor ROI. Ratios of the SUV or SUVmax of tumor to that of cortex (T/C) or that of white matter (T/WM) were calculated.

Statistics

Differences between patients with recurrence and those with radionecrosis were assessed with Student's t tests, two sample, assuming unequal variances. The more robust Wilcoxon rank-sum test with multiple comparison adjustment was applied with a level of 0.002 considered significant.

Results

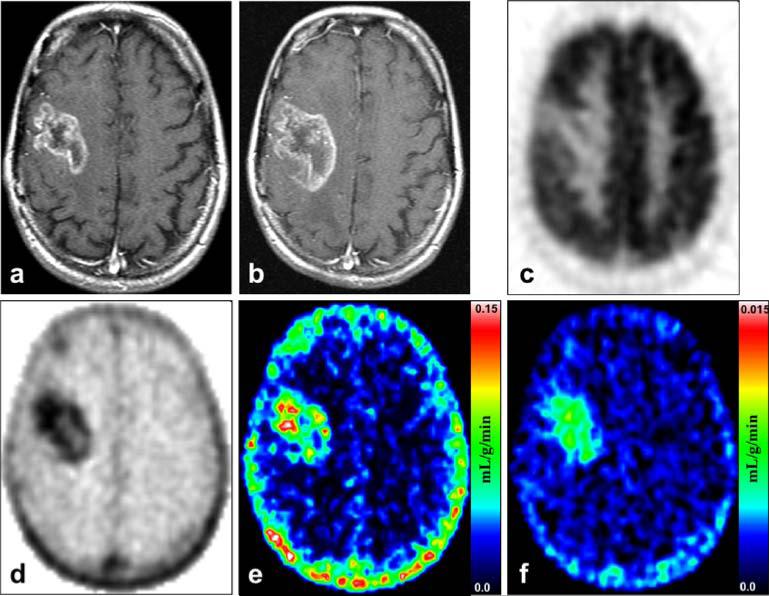

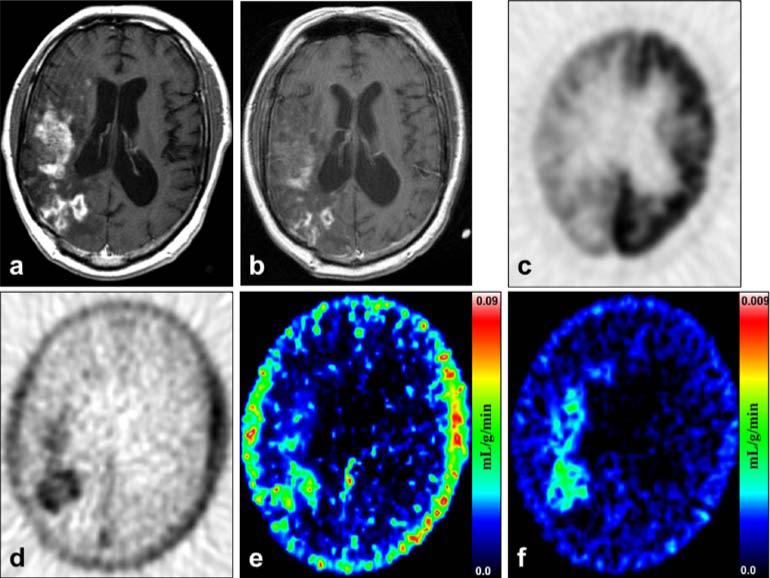

Examples of images representing recurrence and radionecrosis are presented in Figs. 2 and 3. Patient 17 with recurrence shown in Fig. 2 progressed continuously to death with worsening clinical and MRI measures from 2 months before to 6 months after the FLT study despite additional treatment attempts. Patient 1 with radionecrosis shown in Fig. 3 was stable clinically and by MRI assessments for 24 months prior to the FLT-PET. His MRI scans up to 36 months after the FLT-PET showed changes of mildly decreasing contrast enhancement while his dexamethasone dose was progressively tapered. His MR perfusion scan showed iso- or diminished perfusion suggesting the changes were related to radiation rather than progressing tumor.

Fig. 2.

Recurrence: Patient 17 was a 41-year-old woman who died 6 months after the FLT-PET study from progression of her recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. a MRI T1+Gd shows a large right frontal contrast-enhancing lesion at the time of her FLT-PET and FDG-PET scans. b MRI T1+Gd taken 2.5 months after the FLT-PET shows definite progression of the contrast enhancing disease. c FDG-PET of the same plane and time as in a shows that the tumor has uptake focally less than cortex but greater than white matter. d FLT-PET shows a high level of uptake corresponding to the MRI T1+Gd abnormality in a. e Mixture analysis image of the K1 transport parameter. f Mixture analysis image of the KFLT flux parameter. Note that the color scale is ten times less for f than for e.

Fig. 3.

Radionecrosis: Patient 1, a 46-year-old man with a right temporal grade 2 oligodendroglioma diagnosed by biopsy 9 years before FLT-PET and treated with radiotherapy 53 months before FLT-PET. a MRI T1+Gd shows extensive contrast enhancement in the right temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes. b MRI T1+Gd obtained 13 months after the FLT-PET shows decidedly less volume of enhancement. c FDG-PET of the same plane and time as a shows that the tracer uptake is focally greater than white matter but less than cortex. d FLT-PET shows a high level of uptake corresponding closely to the MRI T1+Gd abnormality in a. e Mixture analysis image of the K1 transport parameter. f Mixture analysis image of the KFLT flux parameter. Note that the color scale is ten times less for f than for e.

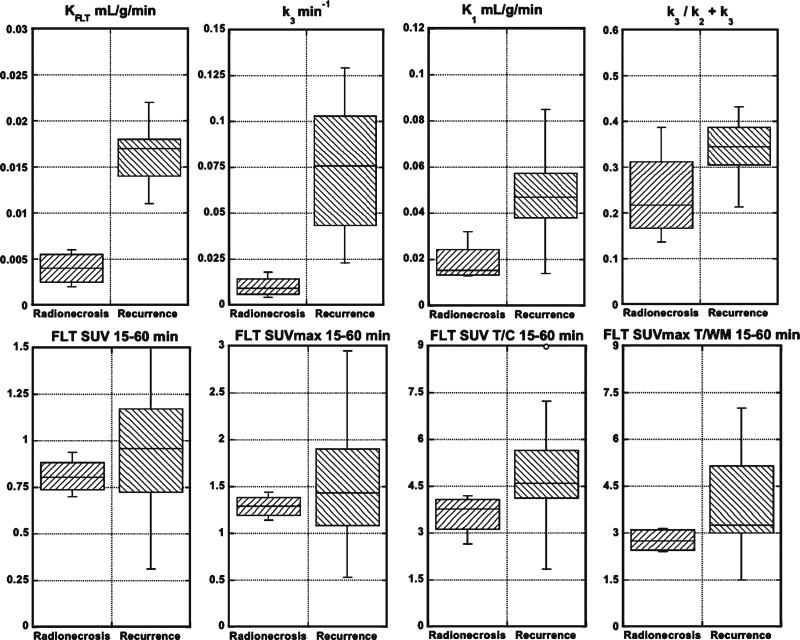

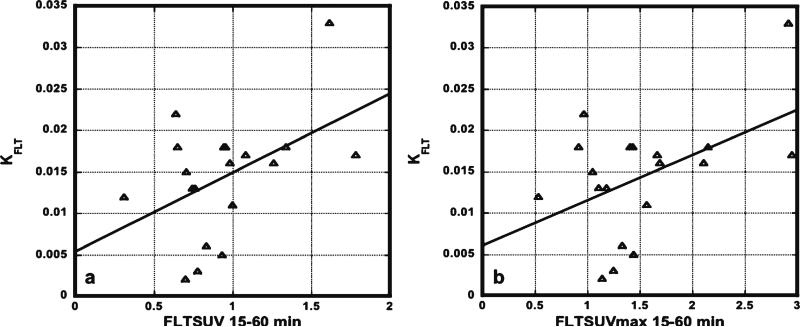

Table 2 shows the FLT-PET results for every patient. Patients 1 through 4 represent the radionecrosis cases and the remainders were recurrences. From these results, the parameters, KFLT, K1, and k3, separated the recurrence from the radionecrosis groups by the t tests (Table 3; Fig. 4). However, by the Wilcoxon tests, only KFLT and k3 reached significance (p=0.0005). K1 was next closest with p=0.0036. The phosphorylation ratio, k3/k2+k3, did not reach significance. Of the multiple ways, we analyzed the SUV results, two reached significance by the t tests, SUV T/C 15–60 min, and SUVmax T/WM 15–60 min, but none did by the Wilcoxon test. Graphical analysis estimates of FLT flux and visual scores did not reach significance. There were poor correlations between KFLT and SUV 15–60 min (R2=0.22; Fig. 5 a) or SUVmax 15–60 min (R2=0.23; Fig. 5b), all 19 patients included.

Table 2.

The results for FLT-PET on all 19 patients

| Case # | K FLT | K 1 | k 2 | k 3 | k 4 | k3/k2 + k3 | SUVmean 15–60 | SUVmax 15–60 | Visual score A | Visual score B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.029 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.386 | 0.94 | 1.44 | 5 | 5 |

| 2 | 0.006 | 0.032 | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.196 | 0.90 | 1.33 | 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.136 | 0.71 | 1.14 | 1 | 4 |

| 4 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.032 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.236 | 0.77 | 1.25 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | 0.011 | 0.035 | 0.098 | 0.042 | 0.020 | 0.299 | 1.00 | 1.57 | 2 | 5 |

| 6 | 0.018 | 0.042 | 0.098 | 0.074 | 0.028 | 0.431 | 0.94 | 1.43 | 3 | 5 |

| 7 | 0.016 | 0.042 | 0.128 | 0.078 | 0.020 | 0.379 | 0.97 | 1.69 | 2 | 5 |

| 8 | 0.016 | 0.050 | 0.069 | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.315 | 1.26 | 2.11 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | 0.017 | 0.047 | 0.105 | 0.060 | 0.029 | 0.365 | 1.09 | 1.67 | 4 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.013 | 0.032 | 0.505 | 0.330 | 0.015 | 0.395 | 0.74 | 1.11 | 3 | 5 |

| 11 | 0.017 | 0.050 | 0.045 | 0.024 | 0.005 | 0.345 | 1.78 | 2.95 | 5 | 4 |

| 12 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.092 | 0.004 | 0.842 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 1 | 3 |

| 13 | 0.018 | 0.058 | 0.170 | 0.076 | 0.027 | 0.310 | 1.337 | 2.15 | 5 | 5 |

| 14 | 0.018 | 0.062 | 0.109 | 0.045 | 0.026 | 0.290 | 0.958 | 1.41 | 4 | 5 |

| 15 | 0.022 | 0.057 | 0.211 | 0.129 | 0.032 | 0.380 | 0.640 | 0.97 | 3 | 5 |

| 16 | 0.013 | 0.040 | 0.227 | 0.105 | 0.028 | 0.316 | 0.759 | 1.18 | 5 | 5 |

| 17 | 0.015 | 0.036 | 0.138 | 0.101 | 0.032 | 0.422 | 0.704 | 1.05 | 2 | 5 |

| 18 | 0.033 | 0.126 | 0.309 | 0.107 | 0.020 | 0.257 | 1.619 | 2.92 | 5 | 5 |

| 19 | 0.018 | 0.085 | 0.085 | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.213 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 1 | 4 |

Table 3.

Results of the statistical analysis of the FLT-PET data

| Variable | t test (p values) | Wilcoxon (p values) |

|---|---|---|

| FLT data | ||

| K FLT | <0.0001 | 0.0005 |

| K 1 | 0.0009 | 0.0036 |

| k 3 | 0.0012 | 0.0005 |

| k3/k2 + k3 | 0.086 | 0.08 |

| SUV 15–60 min | 0.14 | 0.41 |

| SUVmax 15–60 min | 0.16 | 0.66 |

| SUV 60–90 min | 0.67 | 0.88 |

| SUVmax 60–90 min | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| SUV T/C 15–60 min | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| SUVmax T/C 15–60 min | 0.084 | 0.10 |

| SUV T/WM 15–60 min | 0.15 | 0.47 |

| SUVmax T/WM 15–60 min | 0.014 | 0.10 |

| Graphical analysis | 0.51 | 0.47 |

| Visual score A | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| Visual score B | 0.79 | 0.95 |

Note a level of 0.002 is considered significant by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with multiple comparison adjustment

Fig. 4.

Box plots showing the comparisons between the radionecrosis and recurrence groups for KFLT, k3, K1, k3/k2+k3, FLT SUV 15–60 min, FLT SUVmax 15–60 min, FLT SUV T/C 15–60 min, and FLT SUVmax T/WM 15–60 min. See Table 3 for p values.

Fig. 5.

Correlations between KFLT and SUV 15–60 (a) or SUVmax 15–60 (b) were poor (n=19). R2 values were only 0.22 and 0.23, respectively.

There are 13 cases in this report not included in the prior report on dynamic FLT-PET in gliomas from our institution [5]. All of these cases showed blood-brain barrier disruption with MRI T1+Gd enhancement. The results in these 13 additional cases conform to those previously reported with respect to the relationship of K1 and KFLT as well as to the finding that no patient demonstrated FLT uptake outside of the volume of increased permeability defined by MRI T1+Gd enhancement.

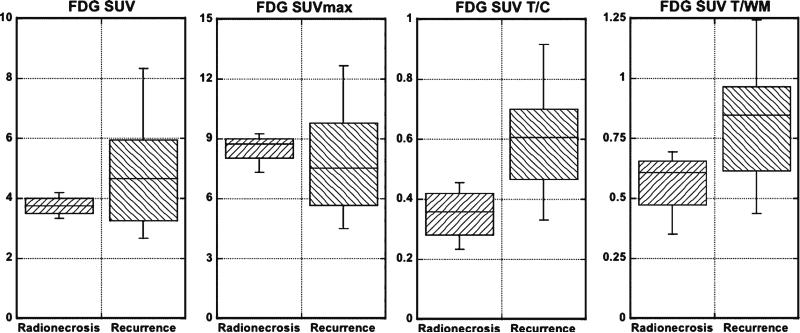

The results of the FDG-PET studies are shown in Tables 4 and 5 and in Fig. 6. These show that the FDGSUV tumor to cortex (T/C) and tumor to white matter (T/WM) ratios distinguished the radionecrosis from the recurrence group by the t tests. None of the measurements separated the two groups by the Wilcoxon tests. Visual analysis by one examiner yielded p<0.004 by the t test. Neither reached significance by the Wilcoxon test.

Table 4.

The results for FDG-PET on 18 patients

| Case # | FDG SUVmean | FDG SUVmax | FDG T/C | FDG T/WM | Visual score A | Visual score B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.20 | 8.74 | 0.455 | 0.620 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 3.81 | 8.41 | 0.386 | 0.594 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 3.78 | 9.07 | 0.331 | 0.694 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 3.32 | 7.31 | 0.233 | 0.350 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | 6.06 | 12.03 | 0.700 | 1.132 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 3.59 | 6.01 | 0.637 | 1.243 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | 4.86 | 7.25 | 0.525 | 0.827 | 5 | 5 |

| 8 | 4.44 | 7.83 | 0.894 | 0.869 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | 6.82 | 9.83 | 0.917 | 1.122 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 | 5.47 | 6.74 | 0.620 | 0.964 | 1 | 3 |

| 11 | 3.23 | 5.40 | 0.468 | 0.612 | 1 | 2 |

| 12 | 5.24 | 9.78 | 0.617 | 0.874 | 1 | 3 |

| 14 | 6.018 | 9.928 | 0.595 | 0.897 | 5 | 4 |

| 15 | 2.678 | 5.662 | 0.425 | 0.615 | 1 | 4 |

| 16 | 3.261 | 8.016 | 0.421 | 0.630 | 5 | 4 |

| 17 | 3.248 | 5.236 | 0.589 | 0.765 | 4 | 4 |

| 18 | 5.954 | 8.247 | 0.878 | 0.607 | 5 | 4 |

| 19 | 2.712 | 4.52 | 0.332 | 0.438 | 1 | 4 |

Table 5.

Results of the statistical analysis of the FDG-PET data

| Variable | t test (p values) | Wilcoxon (p values) |

|---|---|---|

| FDG data | ||

| SUV | 0.08 | 0.65 |

| SUVmax | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| SUV T/C | 0.003 | 0.008 |

| FDGmax T/C | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| SUV T/WM | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| FDGmax T/WM | 0.06 | 0.28 |

| Visual score A | 0.004 | 0.10 |

| Visual score B | 0.89 | 0.82 |

Note a level of 0.002 is considered significant by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with multiple comparison adjustment

Fig. 6.

Box plots showing the comparisons between the radionecrosis and recurrence groups for FDG SUV, FDG SUVmax, FDG SUV T/C, and FDG SUV T/WM. See Table 5 for p values.

Discussion

The intent of this investigation was to explore the capacity of FLT-PET to distinguish recurrence from radionecrosis in previously treated gliomas. The study assumed that monitoring changes in clinical findings and MRI examinations, or lack thereof, through the course of the disease allowed this distinction to be made, since only one case in this report had pathological confirmation. In this and other publications, radionecrosis was assumed when there was no worsening of clinical and MRI examinations over months to years in the absence of any further treatment intervention [6–13]. Recurrence was considered the accurate assessment when clinical deterioration progressed along with worsening MRI findings ending in death. The quality of our results needs to be judged with these limitations in mind, since it may be inaccurate to assume that radionecrosis cannot cause clinical and MRI deterioration ending in death. Also, in this type of study, selection and measurement biases may influence results. Certainly, surgical pathology and/or autopsy findings would provide important supportive evidence to any claim that one or the other process is active in any given case. Doubtless, in a significant percentage of cases, both tumor progression and radionecrosis may be active at the same time in different proportions such that eventual growth of an ineradicable glioma dominates clinical outcome and imaging findings.

That said, the results of the present investigation suggest that FLT-PET may be able to distinguish between recurrence and radionecrosis with dynamic imaging and mathematical modeling to derive parameters of interest. KFLT and k3 were the only measures that reached significance by the Wilcoxon test. KFLT is more reliably assessed than k3 as our prior work showed the precision of the estimates (SEE/mean) over the expected range to be acceptable for KFLT (4% error) but not for k3 (49% error) [5]. The phosphorylation fraction (k3/k2+k3) did not reach significance. Assessed by the Wilcoxon test, all the additional approaches for analyzing the FLT data that did not entail dynamic imaging and parameter estimation failed to distinguish recurrence from radionecrosis in this small data set. These approaches included FLTSUV, FLTSUVmax, simple visual analysis by nuclear medicine specialists, or deriving uptake ratios of tumor/cortex or tumor/white matter regions.

There are now several FLT-PET reports involving gliomas but only a few have addressed the question of tumor recurrence vs radionecrosis. In most of these reports, uptake was assessed by visual and semiquantitative methods such as SUV and SUVmax, or tumor/normal ratios (TNR) [29–33]. Choi et al. reported one case of radionecrosis as a FLT-PET false positive by TNR [30]. Saga et al. showed a case of granuloma after treatment of a GBM that showed FLT uptake by SUVmax and the TNR [32]. These approaches fail to separate the uptake due simply to blood-brain barrier breakdown (transport) from uptake due to retention in the salvage pathway (flux). They risk interpreting any uptake as indicative of proliferation when in reality blood-brain barrier breakdown may be all the images are depicting.

Of more relevance, Schiepers et al. reported seven patients with high-grade gliomas and two with metastatic tumors who underwent dynamic FLT-PET studies [34]. Lesions that were predominantly tumor could be separated from lesions dominated by treatment changes by the parameter, k3, and the phosphorylation fraction (k3/k2+k3). Neither K1 nor flux distinguished between the two groups. Small numbers of patients in their and our studies and different analysis methods could explain why these results differ from ours. This same group reported that FLT-PET separated three stable patients from 15 others with recurrence by means of the FLT SUVmax [29]. However, these three patients lacked contrast enhancement on MRI T1Gd which could be interpreted to mean there was no blood-brain barrier breakdown to allow access of the FLT to the tumor cells.

Our results suggest that FLT-PET performs better than FDG-PET in distinguishing recurrence from radionecrosis. At the time interval of 75–90 min when we imaged, FDG T/C and T/WM ratios reached significance in the t tests but not the Wilcoxon. This time interval is later than was used in prior reports on FDG [7, 10, 35–43]. FDG T/C and T/WM ratios increase with time after injection which may partially explain this trend toward favorable results in a small number of cases [44].

From our data, sensitivity and specificity can be compared with results of other FDG studies, but it must be emphasized that the number of cases in our study is small. With a FDG T/C ratio cutoff of 0.4, the sensitivity and specificity for recurrence calculated to be 93% and 75%, respectively. For T/WM with cutoff of 0.61, sensitivity was 93% again and specificity was 50%.

From other reports, the sensitivity of FDG-PET for distinguishing recurrence of glioma from radionecrosis is typically 73% to 86%, although some reports claim 100% [7, 10, 35–43]. Specificity is problematic in that estimates range from 22% to 100%. Among these reports, methods varied; most included visual analysis or comparison of lesion uptake determined visually or by SUV to a reference noninvolved region such as adjacent or contralateral brain. Imaging usually started at about 45 min postinjection and ended by 60 min. The percentage of patients that had pathology confirmation varied as well. In the instructive report by Ricci et al., there were 31 patients suspected of harboring a recurrence in whom the pathology was positive in 22 and negative in nine [41]. With the cutoff of FDG uptake being greater than white matter, the sensitivity was 86% but the specificity only 22%. With the cutoff set at greater than cortex, the sensitivity was 73% and specificity was 56%.

The results of PET with other tracers so far do not single out a best approach for distinguishing recurrence from radionecrosis. From reviewing several studies, Singhal et al. reported that 11C-l-methionine PET yielded a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 72% for detecting recurrence [45] but more recently, Terakawa et al. reported 75% for both sensitivity and specificity [46]. Chen et al. found that 3,4-dihydroxy-6-18F-fluoro-L-phenylalanine PET separated four patients with radionecrosis from 37 with recurrence [47]. PET with 13N-NH3 separated two patients with radionecrosis from six with recurrence [12]. Despite these many reports, the contribution of PET to this important clinical question obviously still requires further studies that include confirmation by analysis of surgical or autopsy pathology. The same can be said for approaches with single-photon emission computed tomography with Tl-201, technetium-99m hexamethyl propyleneamine oxime, technetium-99m sestamibi, and I-123-α-methyl-l-tyrosine [7, 48–52].

It is beyond the scope of this discussion to present an exhaustive review of magnetic resonance imaging methods and results that bear on the question of recurrence vs radionecrosis. Briefly, estimates of sensitivity range from 64% to 89% and specificity from 83% to 89% when choline/creatinine and choline/n-acetylaspartate ratios are estimated by spectroscopy [50, 53–55]. MR technology and applications are rapidly evolving such that comparisons among the many reports remain challenging. Nevertheless, by measuring metabolite and/or apparent diffusion coefficient ratios, diagnostic accuracy reaches 86% to 96% in selected series [6, 11, 13, 56, 57]. These results set a high bar of performance for PET imagers to exceed especially in a practice environment where MR is becoming nearly universally available ahead of PET.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that FLT-PET is a promising approach for distinguishing recurrence from radionecrosis when applied rigorously with dynamic imaging and mathematical modeling for parameter estimations of flux and K1–k4, but is not useful by estimates of SUV or SUVmax, or visual analysis. Further studies are justifiable but should include surgical pathology and/or autopsy confirmation. FDG-PET may well have more to contribute if rigorous coregistration of the PET images with MRI define better the tumor ROI, and tumor/cortex and tumor/white matter ratios are calculated. Whether delayed interval imaging with FDG (well past 60 min) might better separate radionecrosis from recurrence currently is only a hypothesis, namely that tumor tissue may retain trapped FDG longer than normal brain and the cellular elements associated with necrotic debris.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Pam Pham, Michele F. Wanner, Jeffrey Scharnhorst, and Neha Patel are gratefully acknowledged for their indispensable help. Supported by National Cancer Institute Contract N01-CM-37008 and NIH grants CA42045 and S10 RR17229.

References

- 1.Grierson JR, Schwartz JL, Muzi M, Jordan R, Krohn KA. Metabolism of 3′-deoxy-3′-[F-18]fluorothymidine in proliferating A549 cells: validations for positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Spagnolli F, et al. Disease progression or pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy treatment: pitfalls in neurooncology. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:361–367. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Chalmers L, Van Horn A, Sloan AE. Early necrosis following concurrent Temodar and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:81–83. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spence AM, Muzi M, Link JM, Hoffman JM, Eary JF, Krohn KA. NCI-sponsored trial for the evaluation of safety and preliminary efficacy of FLT as a marker of proliferation in patients with recurrent gliomas: safety studies. Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:271–280. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muzi M, Spence AM, O'Sullivan F, et al. Kinetic analysis of 3′-deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine in patients with gliomas. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1612–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hein PA, Eskey CJ, Dunn JF, Hug EB. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the follow-up of treated high-grade gliomas: tumor recurrence versus radiation injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:201–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn D, Follett KA, Bushnell DL, et al. Diagnosis of recurrent brain tumor: value of 201Tl SPECT vs 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1459–1465. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.6.7992747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim EE, Chung SK, Haynie TP, et al. Differentiation of residual or recurrent tumors from post-treatment changes with F-18 FDG PET. Radiographics. 1992;12:269–279. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.12.2.1561416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichy MP, Bachert P, Hamprecht F, et al. Application of (1)H MR spectroscopic imaging in radiation oncology: choline as a marker for determining the relative probability of tumor progression after radiation of glial brain tumors. RoFo. 2006;178:627–633. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-926744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valk PE, Budinger TF, Levin VA, Silver P, Gutin PH, Doyle WK. PET of malignant cerebral tumors after interstitial brachytherapy. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:830–838. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.6.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weybright P, Sundgren PC, Maly P, et al. Differentiation between brain tumor recurrence and radiation injury using MR spectroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1471–1476. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiangsong Z, Weian C. Differentiation of recurrent astrocytoma from radiation necrosis: a pilot study with (13)N-NH (3) PET. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng QS, Li CF, Liu H, Zhen JH, Feng DC. Distinction between recurrent glioma and radiation injury using magnetic resonance spectroscopy in combination with diffusion-weighted imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reischl G, Blocher A, Wei R, et al. Simplified, automated synthesis of 3′[18F]fluoro-3′-deoxy-thymidine ([18F]FLT) and simple method for metabolite analysis in plasma. Radiochim Acta. 2006;94:447–451. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamacher K, Coenen HH, Stocklin G. Efficient stereospecific synthesis of no-carrier-added 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose using aminopolyether supported nucleophilic substitution. J Nucl Med. 1986;27:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minoshima S, Berger K, Lee K, Mintun M. An automated method for rotational correction and centering of three-dimensional functional brain images. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1579–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham MM, Lewellen BL. High-speed automated discrete blood sampling for positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:1357–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundgren B, Bottiger D, Ljungdahl-Stahle E, et al. Antiviral effects of 3′-fluorothymidine and 3′-azidothymidine in cynomolgus monkeys infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzi M, Mankoff DA, Grierson JR, Wells JM, Vesselle H, Krohn KA. Kinetic modeling of 3′-deoxy-3′-fluorothymidine in somatic tumors: mathematical studies. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewellen TK, Kohlmyer SG, Miyaoka RS, Kaplan MS, Stearns CW, Schubert SF. Investigation of the performance of the General Electric ADVANCE positron emission tomograph in 3D mode. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1996;43:2199–2206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinahan PE, Townsend DW, Beyer T, Sashin D. Attenuation correction for a combined 3D PET/CT scanner. Med Phys. 1998;25:2046–2053. doi: 10.1118/1.598392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mankoff DA, Shields AF, Graham MM, Link JM, Krohn KA. A graphical analysis method to estimate blood-to-tissue transfer constants for tracers with labeled metabolites. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:2049–2057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patlak CS, Blasberg RG. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:584–590. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chishty M, Begley DJ, Abbott NJ, Reichel A. Functional characterisation of nucleoside transport in rat brain endothelial cells. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1087–1090. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000072843.93264.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells JM, Mankoff DA, Muzi M, et al. Kinetic analysis of 2-[11C]thymidine PET imaging studies of malignant brain tumors: compartmental model investigation and mathematical analysis. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:151–159. doi: 10.1162/15353500200202112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Sullivan F. Metabolic images from dynamic positron emission tomography studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1994;3:87–101. doi: 10.1177/096228029400300106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Sullivan F. Imaging radiotracer model parameters in PET: a mixture analysis approach. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1993;12:399–412. doi: 10.1109/42.241867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spence AM, Muzi M, Graham MM, et al. Glucose metabolism in human malignant gliomas measured quantitatively with PET, 1-[C-11] glucose and FDG: analysis of the FDG lumped constant. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:440–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W, Cloughesy T, Kamdar N, et al. Imaging proliferation in brain tumors with 18F-FLT PET: comparison with 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:945–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi SJ, Kim JS, Kim JH, et al. [18F]3′-deoxy-3′-fluorothymidine PET for the diagnosis and grading of brain tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:653–659. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1742-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobs AH, Thomas A, Kracht LW, et al. 18F-fluoro-L-thymidine and 11C-methylmethionine as markers of increased transport and proliferation in brain tumors. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1948–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saga T, Kawashima H, Araki N, et al. Evaluation of primary brain tumors with FLT-PET: usefulness and limitations. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:774–780. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000246820.14892.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto Y, Wong TZ, Turkington TG, Hawk TC, Reardon DA, Coleman RE. 3′-Deoxy-3′-[F-18]fluorothymidine positron emission tomography in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: comparison with Gd-DTPA enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:340–347. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiepers C, Chen W, Dahlbom M, Cloughesy T, Hoh CK, Huang SC. (18)F-fluorothymidine kinetics of malignant brain tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1003–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asensio C, Perez-Castejon MJ, Maldonado A, et al. The role of PET-FDG in questionable diagnosis of relapse in the presence of radionecrosis of brain tumors. Rev Neurol. 1998;27:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chao ST, Suh JH, Raja S, Lee SY, Barnett G. The sensitivity and specificity of FDG PET in distinguishing recurrent brain tumor from radionecrosis in patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Cancer. 2001;96:191–197. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Chiro G, Oldfield E, Wright DC, et al. Cerebral necrosis after radiotherapy and/or intraarterial chemotherapy for brain tumors: PET and neuropathologic studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:189–197. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez-Rio M, Rodriguez-Fernandez A, Ramos-Font C, Lopez-Ramirez E, Llamas-Elvira JM. Diagnostic accuracy of 201Thallium-SPECT and 18F-FDG-PET in the clinical assessment of glioma recurrence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:966–975. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0661-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henze M, Mohammed A, Schlemmer HP, et al. PET and SPECT for detection of tumor progression in irradiated low-grade astrocytoma: a receiver-operating-characteristic analysis. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langleben DD, Segall GM. PET in differentiation of recurrent brain tumor from radiation injury. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1861–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ricci PE, Karis JP, Heiserman JE, Fram EK, Bice AN, Drayer BP. Differentiating recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis: time for re-evaluation of positron emission tomography? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:407–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Laere K, Ceyssens S, Van Calenbergh F, et al. Direct comparison of 18F-FDG and 11C-methionine PET in suspected recurrence of glioma: sensitivity, inter-observer variability and prognostic value. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:39–51. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang SX, Boethius J, Ericson K. FDG-PET on irradiated brain tumor: ten years' summary. Acta Radiol. 2006;47:85–90. doi: 10.1080/02841850500335101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spence AM, Muzi M, Mankoff DA, et al. 18F-FDG PET of gliomas at delayed intervals: improved distinction between tumor and normal gray matter. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1653–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singhal T, Narayanan TK, Jain V, Mukherjee J, Mantil J. (11)CL-methionine positron emission tomography in the clinical management of cerebral gliomas. Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terakawa Y, Tsuyuguchi N, Iwai Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 11C-methionine PET for differentiation of recurrent brain tumors from radiation necrosis after radiotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:694–699. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen W, Silverman DH, Delaloye S, et al. 18F-FDOPA PET imaging of brain tumors: comparison study with 18F-FDG PET and evaluation of diagnostic accuracy. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:904–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dadparvar S, Hussain R, Koffler SP, Gillan MM, Bartolic EI, Miyamoto C. The role of Tc-99m HMPAO functional brain imaging in detection of cerebral radionecrosis. Cancer J. 2000;6:381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez-Rio M, Martinez Del Valle Torres D, Rodriguez-Fernandez A, et al. (201)Tl-SPECT in low-grade gliomas: diagnostic accuracy in differential diagnosis between tumour recurrence and radionecrosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:1237–1243. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lichy MP, Henze M, Plathow C, Bachert P, Kauczor HU, Schlemmer HP. Metabolic imaging to follow stereotactic radiation of gliomas—the role of 1H MR spectroscopy in comparison to FDG-PET and IMT-SPECT. RoFo. 2004;176:1114–1121. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prigent-Le Jeune F, Dubois F, Perez S, Blond S, Steinling M. Technetium-99m sestamibi brain SPECT in the follow-up of glioma for evaluation of response to chemotherapy: first results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:714–719. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soler C, Beauchesne P, Maatougui K, et al. Technetium-99m sestamibi brain single-photon emission tomography for detection of recurrent gliomas after radiation therapy. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:1649–1657. doi: 10.1007/s002590050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ando K, Ishikura R, Nagami Y, et al. Usefulness of Cho/Cr ratio in proton MR spectroscopy for differentiating residual/recurrent glioma from non-neoplastic lesions. Nippon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;64:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hollingworth W, Medina LS, Lenkinski RE, et al. A systematic literature review of magnetic resonance spectroscopy for the characterization of brain tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1404–1411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plotkin M, Eisenacher J, Bruhn H, et al. 123I-IMT SPECT and 1H MR-spectroscopy at 3.0 T in the differential diagnosis of recurrent or residual gliomas: a comparative study. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:49–58. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000040810.77270.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rabinov JD, Lee PL, Barker FG, et al. In vivo 3-T MR spectroscopy in the distinction of recurrent glioma versus radiation effects: initial experience. Radiology. 2002;225:871–879. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253010997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng QS, Li CF, Zhang K, Liu H, Kang XS, Zhen JH. Multivoxel 3D proton MR spectroscopy in the distinction of recurrent glioma from radiation injury. J Neurooncol. 2007;84:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.