Abstract

Stroke is the leading cause of disability in adults world-wide. Well-recognized environmental risk factors for stroke include hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation and atherosclerosis. Ischemic stroke, which accounts for ~85% of all stroke, is mainly caused by either intracranial thrombosis or extracranial embolism; hemorrhagic stroke can be classified as either intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Metalloproteins and metals play key roles in epigenetic events in living organisms, including hypertension, the most important modifiable risk factor for stroke. For example, Zinc (Zn) is located in the catalytic site of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), a component of the renin-angiotensin system which is important for blood pressure regulation., Cadmium, lead, selenium, calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium and other metals are well recognized to be associated with stroke risk and prognosis. Concentrations of metalloproteins in the blood plasma are important factors in a number of diseases including iron overload (hemochromatosis) and copper overload (Wilson’s disease). Exposure to toxic metals and pollutants in the air, water or food can lead to altered metabolism, which may alter levels of metalloproteins in plasma. Metalloproteins may be important for disease diagnosis. Thus, this study sought to develop a method of detecting metals and metalloproteins levels for distinguishing stroke types. In search of these, different analytical techniques such as affinity chromatography, size exclusion chromatography (SEC), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) and electrospray mass spectrometry (ESIMS) were used.

Keywords: Blood Plasma, ESIMS, HPLC, ICPMS, Metalloproteins, Stroke

Graphical abstract

Metalloproteins and metals play key roles in epigenetic events in living organisms, including hypertension, the most important modifiable risk factor for stroke. To detect metalloproteins and metals different analytical techniques, such as affinity chromatography, size exclusion chromatography (SEC), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) and electrospray mass spectrometry (ESIMS) are used.

1. Introduction

Stroke is the 3rd leading cause of death and the leading cause of disability in the USA, accounting for about $74 billion in costs in 2010.1 Stroke is classified as 1) Ischemic stroke (Subtypes: Atherothrombotic, Small vessel disease, Cardiac emboli etc); 2) Hemorrhagic stroke (Subtypes: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, Bleeding diathesis, Vascular malformation etc); and 3) Spinal cord stroke.2 There is no proven therapy for hemorrhagic stroke, and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA), the only approved therapy for ischemic stroke, is given to only ~3% of ~700,000 ischemic stroke patients annually.3 High blood pressure, disorders of heart rhythm (including atrial fibrillation), smoking/tobacco, high blood cholesterol/other lipids, physical inactivity, diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease/chronic kidney disease are well known risk factors for stroke.4

Metalloproteomics and metallomics are promising fields for addressing the storage, role, uptake and transport of trace metals vital for protein functions. The function of these proteins depends on the interaction between the bound metals and proteins.5, 6 About one-third of all proteins are associated with one or more metals. Metalloproteins are one of the most diverse classes of the proteins, contribute to neurodegenerative diseases and play a vital role in biological systems. Many biologically active proteins have essential metal atoms that provide a structural, catalytic and regulatory role critical to protein function.7 Zn, the most abundant transition metal in cells, plays a vital role in the functionalities of more than 300 enzymes, including the stabilization of DNA and gene expression.8 Se, W and Mo are essential in human health and also important in the environment. Transition metals such as Cu, Fe and Zn play important roles in life.9–11 Calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium appear to be involved in hypertension pathogenesis.12

In addition to mediating arterial hypertension, metals have also been associated with stroke risk and prognosis. In a recent analysis of 35 acute stroke patients and 44 controls, stroke severity was associated with transferrin (the main protein regulator of iron homeostasis) (r=−0.48, P=0.004), ceruloplasmin (circulating enzyme typically bound to copper that oxidizes Fe2+ ions) (r=0.43, P=0.012), and stroke lesion volume (r=0.50, P=0.004).13 In another study of 12,049 participants in the 1999–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a 50% increase in blood cadmium corresponded to a 35% increased odds of prevalent stroke (OR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.12–1.65).14 In addition, animal studies suggest that Zn-dependent pathways and Zn dyshomeostasis may contribute to stroke-related brain injury.15 In aggregate, these studies demonstrate that metals and metalloproteins very likely play a key role in how epigenetic differences contribute to stroke phenotype.

Gailer and co-workers recently provided insights into the underlying biomolecular mechanisms of the interaction of plasma proteins with toxic metals.16 Different mobile phase effects of detecting Cu, Fe and Zn metalloproteome pattern in rabbit plasma have been studied using size-exclusion chromatography coupled with an inductively coupled plasma atomic-emission spectrometer (SEC-ICP-AES).17 Analysis of plasma metalloproteome by SEC-ICP-AES can be applied to human diseases that are associated with increased or decreased concentrations of certain plasma metalloproteins.18 It has also been shown that metalloproteins require metal sensors that distinguish between inorganic elements in order to acquire the right metals.19

Concentrations of different levels of trace metals play a key role in determining different neurodegenerative diseases including Cu in Wilson’s disease20, Mg in ischemic stroke21, Cr, Cs and Sn in patients with brain tumors22, multiple sclerosis23, and Alzheimer’s disease24, 25, and trace metals in Parkinson’s disease26.

In this metalloprotein study the elements of interest were Mg, Al, Mn, Cu, Zn, Se, Mo and Pb. Magnesium (Mg) is the fourth most abundant mineral in the body and it is needed for more than 300 biochemical reactions in the body. There is an increased interest in the role of magnesium in preventing and managing disorders such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. “Epidemiologic evidence suggests that magnesium may play an important role in regulating blood pressure”.27 The observed associations between magnesium metabolism, diabetes, and hypertension increase the likelihood that magnesium metabolism may influence cardiovascular disease.28 Magnesium is known to be vasoprotective29, 30 mainly due to binding of, and antagonism by, Mg at calcium channels in smooth muscle.31–36

Aluminum (Al) is the most abundant metallic element in the earth’s crust. It can be absorbed into the body through the digestive tract, skin and the lungs. Aluminum can also accumulate in the brain causing seizures and reduced mental alertness. Elemental aluminum does not pass easily through the blood brain barrier, but certain Al compounds such as aluminum fluoride do. Al increases oxidative stress that is induced by Fe and other metals,37–39 increases neurofibrillary tangle-like endpoints,40–43 and induces apoptosis.44–46

Manganese (Mn) is a trace mineral present in small amounts in the body and found mostly in the liver, kidneys, pancreas and bones. Manganese plays an important role in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, calcium absorption and blood sugar regulation. It is also necessary for normal brain and nerve function.47 Low levels of manganese in the body can contribute to weakness, seizures, infertility and bone malformation. However, excess manganese in the diet could lead to high levels of manganese in the body tissues.48 Early life manganese exposure at high levels, or low levels, may impact neurodevelopment.49 Abnormal concentrations of manganese in the brain, especially in the basal ganglia, are associated with neurological disorders similar to Parkinson’s disease.

Copper (Cu) is the single most important nutrient in the body. A small amount of copper obtained from food is necessary, but too much copper is toxic.50 Copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD1) is a crucial antioxidant enzyme. Decreased superoxide by overexpression of SOD1 protects against development of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), while increased superoxide due to deficiency in SOD1 increases susceptibility to ICH.51

Zinc (Zn) is the second most common mineral in the body, after iron, and is found in every cell. It plays an important role in blood clotting, growth, thyroid function and proper insulin levels. Zinc is essential for normal vascular endothelial function, with both deficiency and toxicity disrupting this function leading to hypertension. Zn toxicity and deficiency have a wide range of physiological manifestations.52, 53

Selenium is usually incorporated into antioxidant enzymes as selenocysteine (SeCys) or selenomethionine (SeMet) and plays a key role in host oxidative defense. The most widely known SeCys-containing enzymes are thioredoxin reductase and glutathione peroxidase. Both are ubiquitous and found in bacteria, plants and mammals, including humans.54 Up to 25 SeCys-containing proteins exist in humans.55–57 Selenium impacts heart and blood vessels diseases, including stroke, given its role in “hardening of the arteries” (atherosclerosis).58

Molybdenum (Mo) is an essential element in human nutrition. Too little molybdenum in the diet may be responsible for various health problems.59 Excess molybdenum can cause abnormalities of the digestive tract, kidneys and liver resulting in poor appetite, nausea and weakness.60, 61 Excess molybdenum also may cause inflammatory spine and joint disease.

Lead (Pb) occurs naturally in the environment and low levels of lead are ingested through food, air, drinking water, soil, household dust and some consumer products. Lead also increases intravascular superoxide and free radical damage62, as well as altering vascular reactivity63, leading to lead-induced hypertension, development disorders, neurotoxicity and death.64 At low level exposure to lead, the main health effect is observed in the nervous system. Specifically, exposure to lead may have subtle effects on the intellectual development of infants and children.

Given the studies above, metalloproteins can clearly be directly related to certain diseases. The capability to compare the levels of these bio-molecules in a very complicated matrix such as plasma would be extremely useful. The following elements were analyzed for total elemental study: 7Li, 23Na, 24Mg, 27Al, 39K, 43Ca, 51V, 55Mn, 56Fe, 59Co, 60Ni, 63Cu, 66Zn, 75As, 78Se, 88Sr, 107Ag, 114Cd, 137Ba, 208Pb, 238U. Human plasma is a complex mixture of virtually all proteins expressed in humans from blood cells and/or tissue through active secretion or leakage. Hence, plasma should contain early markers for all possible diseases. Multiple chromatographic separations reduce the complexity of the plasma samples.65–68 Enhanced separation capabilities, and superior signal to noise ratio, applied to small amounts of samples make micro-fluidic devices a very useful tool as the last step in a shotgun proteomic study.69–71 In this case-control double-blind feasibility study, using chromatography and ICPMS techniques to detect and identify metalloproteins and metals in human plasma that may be useful for stroke diagnosis.

2. Experimental

2.1 Methods overview

Stroke patients who presented to The University of Cincinnati Hospital (TUH) emergency department (ED) were enrolled in a plasma banking project. Informed consent and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval were obtained. Blood draws were performed in the ED, and demographic and clinical information (time of onset, severity etc.) were recorded.

For this project, we analyzed twenty-nine plasma samples collected within 12 hours of symptom onset. Ten samples were controls (the control samples presented here are “stroke mimics”). Stroke mimics are the patients with complicated migraines or other symptoms initially concerning for stroke, but who ultimately did not have a stroke. Of the stroke case, 9 were hemorrhagic stroke and the remaining 10 were ischemic stroke. Demographics on the selected cases and controls are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample descriptions, the group of 29 samples consists of ten controls, nine intracerebral hemorrhage and ten acute ischemic stroke plasma samples. Demographics on the selected cases and controls are presented.

| Control (n=10) | * AIS (n=10) | # ICH (n=9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) Median (range) |

50.5 (33–79) | 72.0 (59–95) | 71.0 (40–82) |

| Race (% Black) | 30.0 | 20.0 | 33.3 |

| Gender (% Female) | 30.0 | 20.0 | 22.2 |

| Smoking (%) | 50.0 | 40.0 | 44.4 |

ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage;

AIS = acute ischemic stroke.

Ninety nine percent of the protein mass in plasma is comprised of twenty-two proteins such as human serum albumin (HSA), immunoglobulins, haptoglobin, transferrin, and lipoproteins, etc. We developed a series of multiple liquid chromatography separations for the plasma proteins. First, affinity chromatography that allowed removal of the two most abundant proteins HSA and IgG, which represent ~70% in mass of the total protein amount in plasma; next, size exclusion chromatography eliminated the low molecular weight compounds and gave an extended fractionation of the proteins present in the samples. This was then followed by ICPMS and nano liquid chromatography chip electrospray ionization (nanoLC-CHIP/ESIMS).

ICPMS represents the state-of-the-art instrumentation when it comes to trace element determination and speciation analysis of metals, metalloids and some biologically important non-metals such as P, S and the halogens. It is an analytical tool that has exceptional detection power (in the parts per trillion ranges) and the ability to analyze different isotopes. Many of these natural isotopes are highly preferred over their radioactive cousins. This detection ability is essential because it is thought that the low molecular weight region (< 100 kDa) is where important, but still unstudied, biological events occur. Furthermore, identification of differentially expressed metalloproteins in plasma would allow for targeted verification of candidate biomarkers for stroke diagnosis. The power and reliability of nanoLC-CHIP/ESIMS was used to identify the tryptic peptides obtained from the size exclusion chromatography-high performance liquid chromatography-diode array detector (SEC-HPLC-DAD) to detect proteins from the samples.

2.2 Apparatus

The human Multiple Affinity Removal System column 4.6 × 50 mm (MARS) was purchased from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA) to deplete HSA and IgG. For the size exclusion chromatography separation, a TSK Gel 3000SW 7.5 × 300 mm (Tosoh Bioscience, Germany) was used. The pre-concentration of samples was done by centrifugation (Sorvall instruments RC5C, Buckinghamshire, England). An Agilent 7700x ICPMS equipped with a plasma frequency-matching RF generator and an octopole collision/reaction system (ORS) was coupled with an Agilent 1100 LC. An Agilent 1100 series HPLC system equipped with a binary pump, vacuum membrane degasser, thermostated auto sampler, column oven, and diode array detector with a semi-micro flow UV-Vis cell was used for all chromatographic analysis (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The entire system was controlled using Chemstation software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For the sample concentration a freeze-dryer (Millrock Technology, NY, U.S.A) was used. Microwave laboratory instrumentation from CEM Corporation (Matthews, NC, U.S.A) was used for sample digestion.

An Agilent 6300 series HPLC-CHIP-ESI-Ion Trap XCT system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) coupled to an Agilent model 1200 LC was used to carry out protein identifications using a capillary binary pump for loading the sample into a microfluidic HPLC-Chip column and with a nano flow binary pump to provide the analytical flow for the RP separation on a Zorbax SB 300A C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

2.3 Reagents and solutions

Methanol, ammonium acetate, bovine serum albumin and formic acid were analytical grade purchased from Sigma. Ammonium bicarbonate, dithiothreitol, iodoacetamide, and acetic acid were purchased from Fluka (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A). Nitric acid (trace metal grade) was purchased from Fisher scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, U.S.A). Double deionized (DDI) water was prepared by passing distilled water through a NanoPure (18 MΩ) treatment system (Barnstead, Boston, MA, USA) and was used to prepare all solutions used in the experiments. For calibrating the SEC column, the SEC standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) mixture of molecular weight markers ranging from 1,300 Da to 670,000 Da was used. The protease used for the peptide mapping of the proteins was the modified sequence grade trypsin from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). For the sample concentration after the MARS system, spin concentrators for proteins (3 kDa MWCO, Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters) from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA) were used. Buffer A and buffer B mobile phases for MARS column and 5 kDa MWCO were purchased from Agilent (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.4 Procedures

2.4.1 Multiple chromatographic separations

The two most abundant proteins were removed in order to reduce the sample complexity. Recent studies show that the MARS system has comparatively high performance compared with other traditional depletion methods available on the market, both in terms of proteome coverage and reproducibility.72, 73 Thus, we used the MARS system for separation. The MARS column was used as directed. In short, the HPLC system was flushed with isopropyl alcohol for 10 minutes followed by flushing with water for 2 hours, then 2 blanks with and without column were injected into the system. The mobile phase used in the affinity chromatography to remove the HSA and IgG is a solution of unknown composition with a high concentration of nonvolatile salts. Plasma samples of 200 μl each were diluted four times with buffer A and 400 μl was injected into the system. The first fraction between 1.5 and 7.5 minutes was collected for further separation and the HSA and IgG retained in the column were eluted using buffer B. This process was carried out twice per sample in order to have enough protein concentration in the depleted fraction. After the fraction collection from the MARS system, the volume was reduced using a 3 kDa MWCO spin filter, the 3 ml collected were reduced to 300 μl by spinning for 35 min at 5,500 g at 4 °C, before preconcentrating the sample. The 3 kDa spin filters were passivated using a passivation solution, which is 0.2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin for two hours. After two hours the passivation solution was removed and rinsed with water thoroughly. Passivation of the spin filters can increase the recovery of the protein samples passed through the membrane filters.

Then following this separation, size exclusion chromatography was utilized. SEC allows removal of low molecular weight compounds present in the plasma, while preserving size based fractions of the proteins in the samples. As mentioned earlier, the mobile phase used in affinity chromatography contains considerable amounts of nonvolatile salts, so using a volatile buffer in the SEC process is necessary to prepare the fractions collected for preconcentration by freeze drying. Before running the actual samples, the column was calibrated with a UV detector (wavelength, 280 nm) by using a gel filtration standard mixture (molecular weight of thyroglobulin, 670 kDa; molecular weight of g-globulin, 158 kDa; molecular weight of ovalbumin, 44 kDa; molecular weight of myoglobin, 17 kDa; molecular weight of vitamin B12, 1.3 kDa (mixture from Bio-Rad Laboratories), with r=0.998. The concentrated samples collected after spinning were then introduced into the HPLC system, using the TSK 3000SW column with a pre-column 0.45 μm inline filter. The mobile phase used was 50 mM ammonium acetate at pH 6.5 with 5% of methanol at a flow rate of 0.7 ml min−1. The addition of methanol decreased the non-specific interaction of the sample with the stationary phase.74 The sample was loaded using a 200 μl loop and injected. After several injections it was observed through loss of resolution that column cleaning was essential. For the analysis, the column was cleaned after two injections (between every sample) by flushing with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 25 minutes as reported,75 followed by 30 minutes of equilibration with the analytical mobile phase. β-mercaptoethanol is used for cleaning the column because it denatures the some of the proteins via its ability to cleave disulfide bonds.

2.4.2 Size Exclusion Chromatography-ICPMS (Metalloproteins)

An Agilent 7700x ICPMS equipped with a plasma frequency-matching RF generator and an octopole collision/reaction system (ORS) was coupled with an Agilent 1100 LC. The instrumental operating conditions were as follows: forward power 1500W, carrier gas flow rate 1.1 l min−1, make-up gas flow rate 0.10 l min−1, nickel sampling and skimmer cones, collision/reaction cell gas He, 4 ml min−1. The isotopes 24Mg, 27Al, 55Mn, 63Cu, 66Zn, 78Se, 95Mo, 207Pb and 208Pb, were monitored. The mobile phase conditions for LC were used as discussed as above: 50 mM ammonium acetate pH 6.5 with 5% of methanol at a flow rate of 0.7 ml min−1.

2.4.3 ICPMS determination for Elements

The wet digestion of samples was carried out as follows: to a 100 μl aliquot of plasma sample 500 μl of 30% nitric acid, 50 μl of internal standard (composed of Sc, In, Ge and Bi), 200 μl of 31% hydrogen peroxide were added and microwave digested using different temperatures and ramp times; after cooling down the volume was brought to 5 ml with deionized water and later introduced to ICPMS system. The instrumental operating conditions were as follows: forward power 1500W, carrier gas flow rate 0.95 l min−1, make-up gas flow rate 0.10 l min−1, nickel sampling and skimmer cones, collision/reaction cell gas He, 4.5 ml min−1. 45Sc, 72Ge, 115In and 209Bi isotopes were used as internal standards. The list of metals analyzed for the study was described above in the introduction. Calibration was performed using the Claritas (SPEX Certiiprep) multi-element standard solution (5% nitric acid (v/v)) at element concentration levels: 0; 0.1; 0.3; 0.5; 1.0; 2.0; 5.0; 10; 25 and 40 μg l−1 with addition of the internal standards (5.0 μg l−1 Sc, 5.0 μg l−1 Ge, 5.0 μg l−1 In and 5.0 μg l−1 Bi).

2.4.4 Tryptic digestion and protein identification

The peaks from the SEC-HPLC were collected and freeze-dried. The typical procedure for tryptic digestion is: the pellet obtained after freeze-drying is resuspended in 25 microliters of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. After resuspension, 2 microliters of 100 mM DTT was added as reducing buffer and the mixture was heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes; this step unfolds the proteins and reduces the disulfide bonds. After cooling the sample, an alkylation was carried out to protect the thiol groups of the cysteine residues by adding 3 microliters of 100 mM iodoacetamide. The mixture was then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 minutes. This avoids the formation of new disulfide bonds, which complicate the peptide assignment from the MS/MS spectra. After the alkylation, 1 microliter of modified sequence grade trypsin solution was added and incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours and then 2 microliters of additional trypsin were added to complete the reaction, followed by incubation at 35 °C for 8 hours. At the end, 2 microliters of formic acid were added to stop the reaction, and the solution was ultra-filtered through a 5 kDa filter to remove the undigested proteins and the unreacted trypsin.

2.4.5 nanoHPLC-ESI-IT-MSMS analysis for protein identification

An Agilent 6300 Series mass spectrometer system, which is equipped with both capillary and nano pumps, was used for mass identification. The chip used for the analysis consists of a Zorbax 300SB C18 enrichment column (4 mm × 75 μm, 5 μm) and a Zorbax 300SB C18 analytical column (150 mm × 75 μm, 5 μm). Two microliters of sample were loaded via the capillary pump onto the on-chip enrichment column. Samples were loaded on to the enrichment column at a flow rate of 3 μL min−1 with a 97:3 ratio of solvent A (0.1% FA, formic acid (v/v), in water) and B (90% ACN (acetonitrile), 0.1% FA (v/v) in water). After the enrichment column was loaded, the on-chip microfluidics switched to the analytical column at a flow rate of 0.3 μL min−1. The following gradient conditions were used in the analysis: 0–5 min, 10% B; 5–85 min, 35%B; 85–90 min, 75% B; 90–95 min, 75% B; 95–98 min, 3% B; 98–105 min, 3% B. Full scan mass spectra were acquired over the m/z range 150–2200 in the positive ion mode (peptide charge: +1 to +3). For MS/MS experiments, experimental conditions consisted of: m/z range: 150–2200; isolation width: 2 m/z units, fragmentation energy: 30–200%, fragmentation time: 40 ms. The ionization system utilized was the microfluidic chip, which is automatically loaded and positioned into the MS nanospray chamber and also contains the electrospray tip.

The MS/MS data obtained from the experiments were exported to the online MASCOT (Matrix Science Inc.) database search engine, and submitted with the following parameters: Taxonomy (Mammals), Enzyme (Trypsin), Missed Cleavages (Two), Fixed modifications (Carbamidomethyl), Peptide tolerance (2 Da), MS/MS tolerance (0.8 Da), Peptide charge (+1,+2,+3) and Instrument (ESI-TRAP). MASCOT then searched against Uniprot database and the reported hits were validated doing a blast analysis of the reported peptides.

2.4.6 Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done using OriginPro; version: 8.5 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, U.S.A) and Statistica; version: 7 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, U.S.A). Statistical graphs (box charts) were used to represent different sets of data.

3. Results and Discussion

The main objective of this project was to detect the levels of metalloproteins and metals in different stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke) and control patients. Multiple chromatographic separations, ICPMS and a proteomics approach were used to detect metalloproteins, which may play a potential role in disease diagnosis. The detection of trace elements in plasma samples was carried out using ICPMS to determine different levels of various metals in stroke and control patients. Data were subjected to statistical evaluation.

Metalloproteins (SEC-ICPMS and ESI-MS/MS)

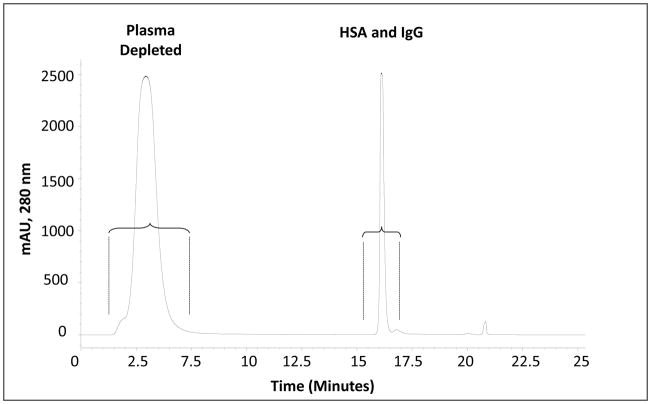

Metalloprotein detection was carried out using liquid chromatography ICPMS and ESI-MS/MS approaches. The first chromatography was immuno depletion of HSA and IgG from the plasma samples using a MARS affinity column, which effectively removed two most abundant proteins; a typical chromatogram for this separation is shown in Figure 1. From the chromatogram it can be observed that HSA and IgG were eluted as a single peak from the column and the fractions collected had high protein concentrations. The presence of HSA and IgG in the labeled fraction was confirmed by analyzing that fraction by SEC. Two signals were observed, collected and analyzed as described above to obtain the protein identification. Only these two proteins were reported as valid hits from the MASCOT search engine against the Uniprot database (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Chromatogram obtained from the immuno depletion of HSA and IgG from the plasma samples, the fraction collected for further separations was between 1.5 and 7.5 minutes for each sample. The fraction at 16 minutes is the HSA and IgG, which were separated from plasma samples after immuno-depletion (Affinity column).

The second separation selected was size exclusion chromatography on the lesser fractions in Figure 1. Its high capacity and its common use as a separation technique on biomolecules, such as proteins, suggested it would be an important part of the protocol.76, 77 This second LC separation shows four regions in the SEC chromatogram (chromatogram not shown). Although these did not allow a single-protein separation in this particular separation, through molecular weight fraction collection it decreased the number of total proteins for identification by ESIMS. It was also possible to discard the low molecular weight compounds eluted at the end of the SEC chromatogram. Using ammonium acetate, a volatile buffer, it was possible to use freeze-drying as an inexpensive preconcentration method in comparison to molecular weight cut-off filters (MWCO) filters.

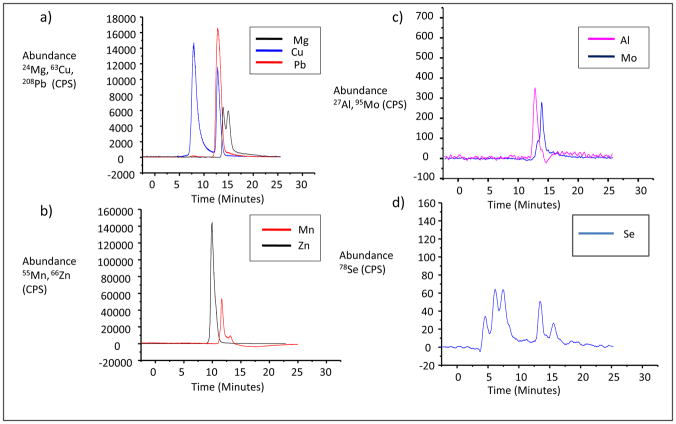

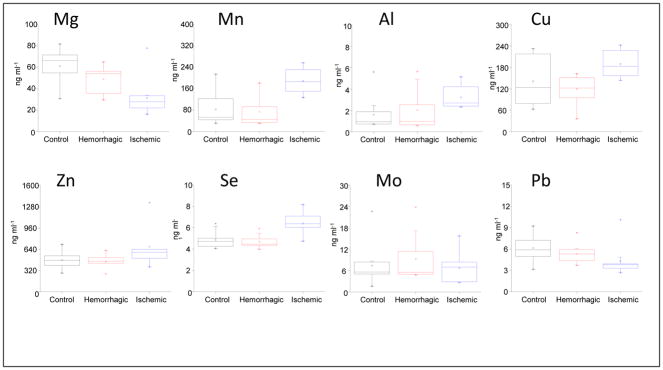

Metalloproteins were detected using the parameters mentioned under procedures. The metals observed were Mg, Al, Mn, Cu, Zn, Se, Mo and Pb. The typical SEC-ICPMS chromatograms for all observed metals are shown in Figure 2. The concentrations and standard deviations of the metalloproteins for controls, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke patients were calculated using origin software and the values are listed in Table 2. In order to statistically evaluate the differences in stroke patients, the Pair-Sample t-Test and statistics (box charts) were performed based on SEC-ICPMS peak concentrations of the fractions. The p-values (Pair-Sample t-Test) were calculated based on three sets of data, which were control vs. ischemic stroke, control vs. hemorrhagic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke vs. ischemic stroke. The p-values for these three sets of data are listed in Table 3. Two sets of data are considered significantly different if the p-value is less than 0.05. In comparison between control vs. ischemic stroke patients, the data were significantly different for metals Mg, Al, Mn, Cu and Se. They were not significantly different for Zn, Mo and Pb. In the comparison between control vs. hemorrhagic stroke, the only significantly different data were with Mg. Interestingly, with the comparison between hemorrhagic vs. ischemic stroke patients, data were significantly different for all metals, except Al. Apart from Pair-Sample t-Test, box chart statistics were performed for all the SEC-ICPMS fraction peak concentration data, and these are shown in Figure 3 for the various metalloproteins. These charts show readily the mean and the overlap or lack thereof, indicating significant differences in various sets of data.

Figure 2.

Typical SEC-ICPMS chromatogram, as a second LC separation. The metal peaks shown above are as follows: a) Mg (Black trace) Cu (Blue trace), Pb (Red trace); b) Mn (Red trace) and Zn (Black trace); c) Al (Pink trace) and Mo (Blue trace) and d) Se containing protein (Blue trace).

Table 2.

Summary of results obtained from the SEC-ICP-MS analysis of the depleted blood plasma. The results are expressed as the means and standard deviations of the concentration for the associated metals in the HMW fractions, expressed as ng ml−1.

| Associated metal | SEC fraction (≈MW range) | Control | Hemorrhagic Stroke | Ischemic Stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std dev | Mean | Std dev | Mean | Std dev | ||

| Mg | 2nd (80 kDa) | 61.2 | 16.5 | 49.0 | 13.4 | 31.5 | 17.3 |

| Al | 1st (100 kDa) | 1.6 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 1.1 |

| Mn | 1st (80 kDa) | 82.9 | 61.4 | 73.6 | 52.1 | 188 | 44.9 |

| Cu | 1st (200 kDa) | 141 | 70.8 | 119 | 42.2 | 190 | 36.4 |

| Zn | 1st (100 kDa) | 477 | 121 | 454 | 116 | 682 | 319 |

| Se | 2nd (150 kDa) | 4.9 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 6.4 | 1.0 |

| Mo | 1st(80 kDa) | 7.4 | 5.7 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 4.2 |

| Pb | 1st (80 kDa) | 59.9 | 18.7 | 52.0 | 13.7 | 41.9 | 20.8 |

Table 3.

The p values are obtained from Pair-Sample t-Test [Origin Pro 8.5 software] between the pairs of (Control : Ischemic stroke), (Control : Hemorrhagic stroke) and (Hemorrhagic stroke : Ischemic stroke). The p value < 0.05 indicates the values (associated metal concentrations) for that particular pair are significantly different from each other. The values in red are < 0.05.

| Associated metal | (Control : Ischemic stroke) | (Control : Hemorrhagic stroke) | (Hemorrhagic : Ischemic stroke) |

|---|---|---|---|

| p value | p value | p value | |

| Mg | <0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Al | <0.01 | 0.39 | 0.05 |

| Mn | <0.01 | 0.27 | <0.01 |

| Cu | 0.03 | 0.63 | <0.01 |

| Zn | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.04 |

| Se | <0.01 | 0.47 | <0.01 |

| Mo | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.04 |

| Pb | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.01 |

Figure 3.

Box charts obtained for all the metalloproteins. Charts obtained from Origin pro software, which describes the statistical difference between the three sets of stroke patients (Control, Hemorrhagic and Ischemic stroke). Box chart are graphical representations of key values from summary statistics and is helpful in quality analysis for rapid initial interpretion of the data distribution (Minimum 25th percentile; median; 75th percentile maximum).

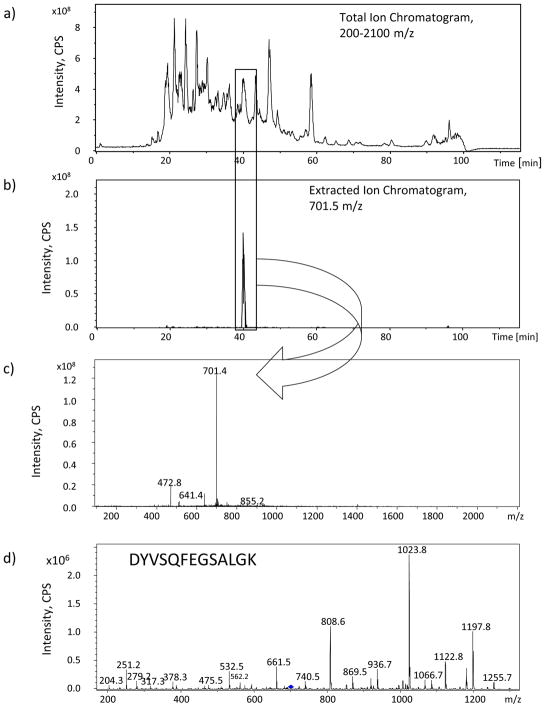

The metalloproteins and proteins present in different sets of samples were identified using nanoHPLC-ESI-IT-MS/MS analysis. An example of the tryptic peptide mapping performed is shown in Figure 4. In brief, from the total ion chromatogram it was possible to obtain the extracted ion chromatogram, based on the m/z isolation range of the precursor ion corresponding to the reported MASCOT peptide. The metalloproteins and proteins found in different sets of blood plasma samples are listed in Table 4. Some proteins listed are involved in diseases like stroke, arterial hypertension or tumor suppressor. For example, transthyretin is a thyroid hormone-binding protein, which transports thyroxine from the bloodstream to the brain.78 It is detected in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Transthyretin is implicated in leptomeningeal amyloidosis, which is characterized by primary involvement of the central nervous system. Some patients also develop vitreous amyloid deposition that leads to visual impairment (oculoleptomeningeal amyloidosis). Clinical features include seizures, stroke-like episodes, dementia, psychomotor deterioration, and variable amyloid deposition in the vitreous humor.79, 80 Microtubule-associated tumor suppressor 1 protein is highly expressed in brain. Its function is to reduce tumor growth and inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation and delays the progression of mitosis by prolonging metaphase.81, 82

Figure 4.

Peptide mapping approach used to assign the protein IDs. a) Total ion chromatogram obtained by nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS, for one of the peaks in the reverse phase separation, after tryptic digestion and identified by MASCOT as Apolipoprotein A-I. Apolipoprotein A-I protein is obtained from SEC fraction 1. b) Extracted ion chromatogram at m/z 701.5 ± 0.3, shows the signal for the peptide DYVSQFEGSALGK as [M-H]2+ ion with good chromatographic behavior. c) MS fragmentation of the ion m/z 701.5. d) MS/MS fragmentation of the ion m/z 701.5.

Table 4.

The list of metalloproteins and proteins found in the blood plasma of controls, hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke patients.

| Proteins | I.D | Metal Binding | Peptide Sequence | Protein score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase listerin | LTN1_HUMAN | Zn | NFLTSLVAGLSTERTK | 34.2 |

| Sodium channel protein type 1 subunit alpha | SCN1A_HUMAN | Na | KQKEQSGGEEK | 31.4 |

| Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 7 | TRPM7_HUMAN | Ca, Zn | FRLIYNSLGGNNRR | 35.6 |

| Probable protein phosphatase 1N | PPM1N_HUMAN | Mg, Mn | ERERIHAAGGTIR | 34.1 |

| Probable phospholipid-transporting ATPase IK | AT8B3_HUMAN | Mg | GGETVIRAGMGDSPGRGAPER | 32.1 |

| Transcriptional activator GLI3 | GLI3_HUMAN | Zn | MEAQSHSSTTTEKKK | 32.2 |

| MOSC domain-containing protein 1, mitochondrial | MOSC1_HUMAN | Mo | RPHQIADLFRPK | 50.5 |

| Stromelysin-1 | MMP3_HUMAN | Ca, Zn | TFPGIPKWRK | 30.1 |

| DNA nucleotidylexotransferase | TDT_HUMAN | Mg | VDSDQSSWQEGKTWK | 39.6 |

| Probable JmjC domain-containing histone demethylation protein 2C | JHD2C_HUMAN | Fe, Zn | QDMDVERSVSDLYKMK | 38.9 |

| Transthyretin | TTHY_HUMAN | GSPAINVAVHVFR | 43.0 | |

| Protein SZT2 | SZT2_HUMAN | RLDEATLDVITVMLVR | 39.4 | |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase MARK2 | MARK2_HUMAN | Mg | RFSDQAAGPAIPTSNSYSK | 47.6 |

| Lactotransferrin | TRFL_HUMAN | Fe | MKLVFLVLLFLGALGLCLAGR | 47.4 |

| Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase epsilon | PTPRE_HUMAN | MPNGILEEQEQQR | 16.8 | |

| Membrane-associated guanylate kinase, WW and PDZ domain-containing protein 2 | MAGI2_HUMAN | KVLCGGEPCPENGRSPGSVSTHHSSPR | 15.9 | |

| Microtubule-associated tumor suppressor 1 | MTUS1_HUMAN | TDDNSDDKIEDELQTFFTSDK | 45.9 | |

| Adenylate cyclase type 4 | ADCY4_HUMAN | Mg | AEEEDEKGTAGGLLSSLEGLK | 55.3 |

| Ecto-NOX disulfide-thiol exchanger 2 | ENOX2_HUMAN | Cu | DDSKFSEAVQTLLTWIER | 45.0 |

| Coagulation factor X | FA10_HUMAN | Ca | NTEQEEGGEAVHEVEVVIK | 35.6 |

| Collagen alpha-1(IV) chain | CO4A1_HUMAN | GEKGQAGPPGIGIPGLR | 34.6 | |

| Cytochrome P450 2C19 | CP2CJ_HUMAN | Fe | DFIDCFLIK | 37.3 |

| Terminal uridylyltransferase 7 | TUT7_HUMAN | Mg, Mn, Zn | HSGLRNILPITTAK | 46.2 |

| Sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger 2 | NCKX2_HUMAN | Ca, K, Na | QNGAANHVEK | 46.1 |

| DBH-like monooxygenase protein 1 | MOXD1_HUMAN | Cu | DFSINLLVCLLLLSCTLSTKSL | 55.4 |

| Nuclear receptor corepressor 2 | NCOR2_HUMAN | NHARKQWEQK | 41.0 | |

| A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 4 | ATS4_HUMAN | Zn | EEEIVFPEKLNGSVLPGSGAPAR | 49.3 |

| Adenomatous polyposis coli protein 2 | APC2_HUMAN | EPAVTKDPGPGGGRDSSPSPR | 56.9 | |

| Transcription factor HIVEP2 | ZEP2_HUMAN | Zn | KPPGNVISVIQHTNSLSRPNSFER | 55.3 |

| Voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit alpha-1C | CAC1C_HUMAN | Ca | LMGSAGNATISTVSSTQRKR | 60.4 |

| Glutamate [NMDA] receptor subunit epsilon-4 | NMDE4_HUMAN | Ca, Mg | TPAAAAPHHHRHR | 56.7 |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1_HUMAN | DYVSQFEGSALGK | 50.0 | |

| Fibrinogen alpha chain | FIBA_HUMAN | ALTDMPQMR | 43.9 | |

| Fibrinogen gamma chain | FIBG_HUMAN | Ca | YLQEIYNSNNQK | 38.4 |

| Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 | PON1_HUMAN | Ca | IQNILTEEPK | 54.8 |

| Serotransferrin | TRFE_HUMAN | Fe | DYELLCLDGTR | 58.0 |

| Prothrombin | THRB_HUMAN | Ca | SPQELLCGASLISDR | 64.5 |

| Angiotensinogen | ANGT_HUMAN | SLDFTELDVAAEK | 63.2 |

Type IV collagen is the major structural component of glomerular basement membranes. The C-terminal half of collagen alpha-1(IV) chain protein is found to possess the anti-angiogenic activity. It specifically inhibits endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation.83–85 Arresten, comprising the C-terminal NC1 domain, inhibits angiogenesis and tumor formation.86 Defects in collagen alpha-1(IV) chain are a cause of brain small vessel disease with hemorrhage. Brain small vessel diseases underlie 20 to 30 percent of ischemic strokes and a larger proportion of intracerebral hemorrhages.87–89 Apolipoprotein A-I is the major protein of plasma high-density lipoprotein, and is also found in chylomicrons. It participates in the reverse transport of cholesterol from tissues to the liver for excretion by promoting cholesterol efflux from tissues and by acting as a cofactor for the lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase. 90 Defects in Apolipoprotein A-I are a cause of high-density lipoprotein deficiency type 2, also known as familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia. Inheritance is autosomal dominant. Apolipoprotein A-I defects are a cause of amyloidosis type 8, which is a hereditary generalized amyloidosis due to deposition of apolipoprotein A1, fibrinogen and lysozyme amyloids. Clinical features include renal amyloidosis resulting in nephrotic syndrome, arterial hypertension and hepatosplenomegaly cholestasis.91–93

Prothrombin protein is expressed by liver and secreted in plasma. Prothrombin functions in blood homeostasis, inflammation and wound healing.94 Thrombin, which cleaves bonds at Arg and Lys, converts fibrinogen to fibrin. Genetic variations in prothrombin may be a cause of susceptibility to ischemic stroke.95 Defects in prothrombin are the cause of factor II deficiency, which is a very rare blood coagulation disorder characterized by mucocutaneous bleeding symptoms.96, 97 Angiotensinogen protein is an essential component of the renin-angiotensin system, a potent regulator of blood pressure, body fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. In response to lowered blood pressure, the enzyme renin cleaves angiotensinogen to produce angiotensin-1 (angiotensin 1-10).98–100 It is expressed by the liver and secreted in plasma. Genetic variations in angiotensinogen are a cause of susceptibility to essential hypertension.

Trace metals in blood plasma (ICPMS)

A total of 21 elements were analyzed on control, hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke plasma as per the procedure discussed above. The analytical accuracy was demonstrated by analyzing National Research Council Canada (NRCC) DORM-3 certified reference material and by the method of standard addition. For analyses of certified reference material, the results obtained were for Ni 1.67 ± 0.20 mg/kg, for Cu 18.7 ± 0.70 mg/kg, for Zn 59.2 ± 3.5 mg/kg, for As 10.0 ± 0.25 mg/kg, for Cd 0.30 ± 0.02 mg/kg and for Pb 0.37 ± 0.06 mg/kg (Certified values respectively: for Ni 1.28 ± 0.24 mg/kg, for Cu 15.5 ± 0.63 mg/kg, for Zn 51.3 ± 3.1 mg/kg, for As 6.88 ± 0.30 mg/kg, for Cd 0.29 ± 0.02 mg/kg and for Pb 0.39 ± 0.05 mg/kg). The mean elemental concentrations along with standard error of the mean (SEM) values are reported in Table 5. Standard error of the mean was preferred over standard deviation based on the diversity and variability of the samples from patients of varying medical history. Highest mean metal concentration levels for control patients were observed for Na (1090 μg/ml) followed by K (885 μg/ml), Mg (19.2 μg/ml), Zn (6.26 μg/ml), Ca (5.06 μg/ml), Al (2.60 μg/ml) and Cu (1.02 μg/ml). Highest mean metal concentration levels for ischemic stroke patients were observed for Na (1050 μg/ml) followed by K (1150 μg/ml), Mg (18.4 μg/ml), Zn (11.8 μg/ml), Ca (5.09 μg/ml), Al (3.13 μg/ml) and Cu (1.04 μg/ml). K (29%), Zn (88%), Ca (0.5%), Al (20%), Cu (1.9%) were higher and Na (3.8%), Mg (4.2%) were lower for ischemic stroke than the control patients.

Table 5.

The data are for the trace elements found in the blood plasma of control, hemorrhagic and ischemic patient samples. The table is divided into two parts a) The concentration for trace elements are reported in ng/ml; b) The concentration for trace elements are in μg/ml. SEM is the standard error of the mean and relatively high values are expected since the mean comes from samples of varying patient histories.

| Elements | Control | Hemorrhagic stroke | Ischemic stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (ng/ml) | SEM | Mean (ng/ml) | SEM | Mean (ng/ml) | SEM | |

| Li | 34.3 | 16.7 | 36.7 | 16.2 | 59.8 | 13.2 |

| V | 2.71 | 0.24 | 3.67 | 0.67 | 4.42 | 0.37 |

| Mn | 3.18 | 2.56 | 7.71 | 6.73 | 6.38 | 1.83 |

| Fe | 363 | 95.8 | 472 | 174 | 347 | 100 |

| Co | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.22 |

| Ni | 27.8 | 23.1 | 10.7 | 6.97 | 62.6 | 53.1 |

| As | 7.10 | 3.45 | 11.1 | 4.60 | 8.98 | 3.57 |

| Se | 161 | 7.93 | 160 | 8.43 | 169 | 8.92 |

| Sr | 41.2 | 4.41 | 55.1 | 7.17 | 56.1 | 2.97 |

| Ag | 43.1 | 11.4 | 22.5 | 5.83 | 88.8 | 20.3 |

| Cd | 0.66 | 0.36 | 1.30 | 0.43 | 1.89 | 1.09 |

| Ba | 584 | 47.4 | 863 | 146 | 964 | 143 |

| Pb | 1.56 | 0.68 | 6.40 | 3.15 | 3.34 | 1.08 |

| U | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| b) | Mean (μg/ml) | SEM | Mean (μg/ml) | SEM | Mean (μg/ml) | SEM |

| Na | 1090 | 39.9 | 1090 | 29.9 | 1050 | 34.2 |

| Mg | 19.2 | 0.78 | 19.0 | 0.91 | 18.4 | 0.75 |

| Al | 2.60 | 1.15 | 5.64 | 2.84 | 3.13 | 1.19 |

| K | 885 | 48.3 | 1130 | 127 | 1150 | 144 |

| Ca | 5.06 | 1.18 | 5.09 | 0.34 | 5.09 | 2.08 |

| Cu | 1.02 | 0.09 | 1.01 | 0.08 | 1.04 | 0.06 |

| Zn | 6.26 | 0.58 | 7.40 | 1.07 | 11.8 | 1.77 |

Highest mean metal concentration levels for hemorrhagic stroke patients were observed for Na (1090 μg/ml) followed by K (1130 μg/ml), Mg (19.0 μg/ml), Zn (7.40 μg/ml), Ca (5.09 μg/ml), Al (5.64 μg/ml) and Cu (1.01 μg/ml). K (27%), Zn (18.2%) and Al (116%) levels were significantly higher in the hemorrhagic stroke patients than the control patients. The data on metal-to-metal correlations in the plasma of control, hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke patients are given in Tables 6 (a–c). The correlations were done based on Pearson correlation coefficient (r) values which were obtained using Statistica Software. Correlation studies are used for finding relationships between variables. Three possible results for correlation studies are: positive, negative and no correlation. The correlation coefficient is a measure of correlation strength and can range from −1.00 to +1.00. Limitation of correlation studies is they can suggest that there is a relationship between two variables; they cannot prove one variable causes a change in another variable. Very strong positive correlations for control patients were found between Mn-Ni (r=1.00), Li-Al (r=0.98), Co-Ni (r=0.97), Al-As (r=0.97), Mn-Co (r=0.96), Li-As (r=0.93), V-Ba (r=0.89), V-Zn (r=0.88), Zn-Ba (r=0.88), As-U (r=0.88), Pb-U (r=0.87) and As-Pb (r=0.85). In addition, significant correlations were also noted between various metals which are highlighted in red in Table 6(a). For hemorrhagic stroke patients, very strong positive correlations were found between Ni-Pb (r=0.98), V-Mn (r=0.93), Mn-Pb (r=0.92), Mn-Ni (r=0.91), Al-Mn (r=0.90), Li-As (r=0.89), K-Ba (r=0.89), V-Zn (r=0.87) and V-Pb (r=0.86). In addition, significant correlations were also noted between various metals, which are highlighted in Table 6(b).

Table 6 (a).

Pearson correlation (r) coefficient matrix of metals in the blood plasma of control patients. Bold values in red are significant at p < 0.05. The values in bold red also indicate that there is a strong interaction between certain metals, for example with Li-Al, Na-Mg etc.

| Li | Na | Mg | Al | K | Ca | V | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Sr | Ag | Cd | Ba | Pb | U | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.98 | −0.25 | −0.58 | 0.09 | −0.15 | −0.22 | 0.05 | −0.14 | −0.02 | −0.26 | 0.93 | −0.05 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.68 | 0.78 |

| Na | 1.00 | 0.71 | −0.04 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.67 | −0.36 | −0.20 | −0.36 | −0.40 | −0.19 | 0.45 | −0.10 | 0.69 | −0.17 | −0.50 | −0.42 | 0.39 | −0.40 | −0.39 | |

| Mg | 1.00 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.38 | −0.13 | −0.66 | −0.47 | −0.08 | −0.14 | −0.30 | ||

| Al | 1.00 | −0.24 | −0.60 | 0.14 | −0.18 | −0.24 | 0.00 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.97 | −0.10 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.84 | |||

| K | 1.00 | −0.18 | 0.65 | −0.15 | −0.04 | −0.22 | −0.17 | 0.44 | 0.63 | −0.15 | 0.61 | 0.44 | −0.38 | 0.45 | 0.79 | −0.13 | −0.24 | ||||

| Ca | 1.00 | −0.11 | 0.38 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.34 | −0.19 | 0.04 | −0.59 | −0.04 | −0.46 | −0.51 | −0.35 | −0.30 | −0.41 | −0.68 | |||||

| V | 1.00 | −0.40 | −0.15 | −0.40 | −0.42 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.20 | 0.64 | 0.34 | −0.19 | 0.31 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Mn | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.51 | −0.27 | −0.17 | −0.46 | −0.04 | −0.38 | 0.11 | −0.31 | 0.26 | −0.03 | |||||||

| Fe | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.10 | −0.01 | −0.18 | −0.26 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.20 | −0.05 | ||||||||

| Co | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.58 | −0.30 | −0.03 | −0.56 | −0.05 | −0.25 | 0.03 | −0.28 | 0.32 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| Ni | 1.00 | 0.51 | −0.26 | −0.16 | −0.50 | −0.06 | −0.32 | 0.11 | −0.29 | 0.27 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Cu | 1.00 | 0.13 | −0.04 | −0.23 | 0.20 | −0.36 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.15 | −0.03 | |||||||||||

| Zn | 1.00 | −0.09 | 0.36 | 0.11 | −0.18 | 0.34 | 0.88 | −0.07 | −0.10 | ||||||||||||

| As | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 0.88 | |||||||||||||

| Se | 1.00 | 0.24 | −0.44 | 0.02 | 0.51 | −0.27 | −0.28 | ||||||||||||||

| Sr | 1.00 | 0.27 | 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 0.58 | |||||||||||||||

| Ag | 1.00 | 0.21 | −0.09 | 0.44 | 0.70 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cd | 1.00 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 0.49 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ba | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.10 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pb | 1.00 | 0.87 | |||||||||||||||||||

| U | 1.00 |

Table 6 (c).

Pearson correlation (r) coefficient matrix of metals in the blood plasma of ischemic stroke patients. Bold values in red are significant at p < 0.05. The values in bold red also indicate that there is a strong interaction between certain metals for example, with Li-Al, Na-Mg etc.

| Li | Na | Mg | Al | K | Ca | V | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Sr | Ag | Cd | Ba | Pb | U | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li | 1.00 | −0.21 | −0.21 | 0.86 | −0.35 | −0.42 | −0.44 | −0.24 | −0.53 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.60 | −0.43 | 0.90 | −0.61 | −0.12 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.27 | 0.58 | 0.74 |

| Na | 1.00 | 0.76 | −0.34 | −0.24 | 0.81 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.71 | −0.21 | 0.00 | 0.16 | −0.38 | 0.59 | −0.15 | 0.06 | −0.26 | −0.16 | 0.34 | −0.42 | |

| Mg | 1.00 | −0.52 | −0.16 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.47 | 0.41 | 0.08 | −0.15 | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.37 | −0.46 | ||

| Al | 1.00 | −0.17 | −0.52 | −0.26 | −0.01 | −0.34 | −0.14 | −0.25 | 0.36 | −0.34 | 0.97 | −0.60 | −0.15 | 0.26 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.35 | 0.77 | |||

| K | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.67 | −0.25 | 0.20 | −0.39 | 0.83 | −0.18 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.19 | −0.43 | 0.97 | −0.24 | −0.10 | ||||

| Ca | 1.00 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.35 | −0.14 | −0.12 | 0.46 | −0.58 | 0.87 | −0.33 | −0.19 | −0.20 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.53 | |||||

| V | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.14 | −0.39 | −0.04 | 0.74 | −0.26 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.47 | −0.52 | 0.64 | 0.08 | −0.15 | ||||||

| Mn | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.64 | −0.24 | −0.39 | 0.42 | −0.07 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.41 | −0.48 | 0.49 | 0.14 | −0.13 | |||||||

| Fe | 1.00 | 0.43 | −0.14 | −0.40 | 0.73 | −0.37 | 0.48 | 0.19 | −0.11 | −0.41 | 0.72 | −0.18 | −0.33 | ||||||||

| Co | 1.00 | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.24 | −0.19 | 0.29 | −0.15 | |||||||||

| Ni | 1.00 | −0.33 | −0.06 | −0.22 | −0.13 | −0.27 | −0.18 | −0.17 | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.19 | ||||||||||

| Cu | 1.00 | −0.13 | 0.49 | −0.27 | 0.44 | −0.14 | 0.14 | −0.21 | 0.65 | 0.54 | |||||||||||

| Zn | 1.00 | −0.35 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.06 | −0.48 | 0.88 | −0.07 | −0.23 | ||||||||||||

| As | 1.00 | −0.69 | 0.03 | 0.23 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.48 | 0.86 | |||||||||||||

| Se | 1.00 | −0.27 | −0.03 | −0.23 | 0.31 | −0.25 | −0.71 | ||||||||||||||

| Sr | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.24 | |||||||||||||||

| Ag | 1.00 | −0.20 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.19 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cd | 1.00 | −0.42 | −0.07 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ba | 1.00 | −0.09 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pb | 1.00 | 0.61 | |||||||||||||||||||

| U | 1.00 |

Table 6 (b).

Pearson correlation (r) coefficient matrix of metals in the blood plasma of hemorrhagic stroke patients. Bold values in red are significant at p < 0.05. The values in bold red also indicate that there is a strong interaction between certain metals, for example with Li-As, Na-Ca etc.

| Li | Na | Mg | Al | K | Ca | V | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Sr | Ag | Cd | Ba | Pb | U | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li | 1.00 | 0.16 | −0.60 | 0.42 | −0.33 | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.34 | −0.31 | −0.20 | −0.30 | −0.31 | 0.89 | −0.27 | 0.58 | 0.02 | −0.61 | −0.18 | −0.01 | 0.49 |

| Na | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.54 | −0.48 | 0.35 | −0.04 | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.57 | −0.23 | −0.15 | 0.80 | 0.35 | 0.33 | |

| Mg | 1.00 | −0.18 | 0.64 | 0.64 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.26 | −0.50 | 0.70 | −0.04 | −0.52 | 0.31 | 0.47 | −0.02 | −0.20 | ||

| Al | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.71 | −0.39 | 0.59 | 0.68 | −0.04 | 0.65 | −0.43 | 0.26 | 0.59 | 0.82 | 0.75 | |||

| K | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.76 | −0.17 | 0.71 | 0.33 | −0.43 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.37 | 0.04 | ||||

| Ca | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.65 | −0.29 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.60 | −0.15 | 0.61 | 0.54 | −0.17 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.28 | −0.12 | |||||

| V | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.83 | −0.01 | 0.87 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.50 | −0.16 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.38 | ||||||

| Mn | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.91 | −0.27 | 0.79 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.48 | −0.48 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.56 | |||||||

| Fe | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.27 | −0.27 | 0.36 | −0.17 | 0.65 | 0.04 | −0.50 | 0.34 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Co | 1.00 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.05 | −0.25 | −0.43 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| Ni | 1.00 | −0.32 | 0.72 | 0.10 | −0.16 | 0.40 | −0.35 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.40 | ||||||||||

| Cu | 1.00 | 0.14 | −0.54 | 0.27 | −0.06 | 0.44 | −0.18 | −0.03 | −0.37 | −0.70 | |||||||||||

| Zn | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.37 | 0.24 | −0.14 | 0.43 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.27 | ||||||||||||

| As | 1.00 | −0.18 | 0.52 | −0.25 | −0.37 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.83 | |||||||||||||

| Se | 1.00 | −0.08 | −0.38 | −0.15 | 0.59 | −0.26 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||||

| Sr | 1.00 | −0.18 | −0.06 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.26 | |||||||||||||||

| Ag | 1.00 | −0.37 | −0.35 | −0.31 | −0.54 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cd | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.67 | 0.01 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ba | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.27 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pb | 1.00 | 0.50 | |||||||||||||||||||

| U | 1.00 |

Very strong positive correlations for ischemic stroke patients were found between Al-As (r=0.97), K-Ba (r=0.97), Li-As (r=0.90), Zn-Ba (r=0.88), Ca-Se (r=0.87), As-U (r=0.86) and Li-Al (r=0.86). Significant correlations are also noted between various metals which are highlighted in Table 6(c). This simple correlation study reveals some common origin of these metals in the plasma of stroke patients. On the basis of the above observation it can be concluded that essential metals such as Mn, Cu and Zn are directly related with the toxic trace metals such as Pb and Ni, suggesting the uptake of these toxic metals in stroke patients. Among some of these selected metals: Cu (in control patients); Co, Sr, Ag (in hemorrhagic patients) and Ni, Sr, Ag, Cd (in ischemic stroke patients) were not significantly correlated with any other metal, suggesting possible independent roles. The relationship between pairs of metals in the plasma of three sets of groups shows a marked difference in metal-to-metal correlations. Na-Mg, Li-Al, Mn-Fe and Mn-Co were strongly correlated in control and ischemic stroke samples when compared to hemorrhagic stroke patient samples. Al-Mn, V-Mn, K-Se and Mg-Se were strongly correlated in hemorrhagic compared to control and ischemic stroke patients. Cu-Pb, Na-Co and As-Se were strongly correlated in ischemic compared to control and hemorrhagic stroke patients.

In this study, statistically significant differences were observed between different sets of patients for metalloprotein data but not for the total metals data. This observation could be due to the fact that we removed the two most abundant proteins (HSA and IgG) by affinity chromatography and further used SEC-ICPMS to detect metalloproteins. Our approach clearly detected the metals bound to proteins separate from metals that otherwise abound in plasma. So, detecting metalloproteins by the removal of most abundant proteins could be very useful identifying candidate protein biomarkers for diseases.

4. Conclusion

Using SEC-ICPMS as a screening tool for detecting high molecular weight fractions, associated with different metals in blood plasma between different stroke patients, is an effective and efficient approach for seeing differences in fractions of specific metal containing proteins. The immune depletion of the HSA allows focusing on functional metalloprotein levels, discarding the bulk of non-functional storing levels of the free metals. Pair-Sample t-Test and statistics (box charts) further showed statistical differences between these metalloproteins that may represent different stroke phenotypes. This study was also able to bring out marked differences in the distribution and correlations of selected trace metals in the blood plasma of stroke samples compared to control samples or different types of stroke samples.

Acknowledgments

We thank Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training grant (CCTST) [“Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award, NIH/NCRR Grant Number UL1RR026314.”], University of Cincinnati College of Medicine for its support for this research.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, Donnan GA, Hennerici MG. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:493–501. doi: 10.1159/000210432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 42:1952–1955. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams HP, Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EF. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–1711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tainer JA, Roberts VA, Getzoff ED. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1991;2:582–591. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(91)90084-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degtyarenko K. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:851–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis J, Del Castillo E, Montes Bayon M, Grimm R, Clark JF, Pyne-Geithman G, Wilbur S, Caruso JA. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:3747–3754. doi: 10.1021/pr800024k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3173–3178. doi: 10.1021/pr0603699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:196–201. doi: 10.1021/pr050361j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Elmi S, Rosato A. Proteins. 2007;67:317–324. doi: 10.1002/prot.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:209–216. doi: 10.1021/pr070480u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekmekci OB, Donma O, Tunckale A. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;95:203–210. doi: 10.1385/BTER:95:3:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altamura C, Squitti R, Pasqualetti P, Gaudino C, Palazzo P, Tibuzzi F, Lupoi D, Cortesi M, Rossini PM, Vernieri F. Stroke. 2009;40:1282–1288. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.536714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters JL, Perlstein TS, Perry MJ, McNeely E, Weuve J. Environ Res. 2010;110:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sensi SL, Paoletti P, Bush AI, Sekler I. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:780–791. doi: 10.1038/nrn2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jahromi EZ, Gailer J. Dalton Trans. 2010:329–336. doi: 10.1039/b912941n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahromi EZ, White W, Wu Q, Yamdagni R, Gailer J. Metallomics. 2010;2:460–468. doi: 10.1039/c003321a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manley SA, Gailer J. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2009;6:251–265. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldron KJ, Rutherford JC, Ford D, Robinson NJ. Nature. 2009;460:823–830. doi: 10.1038/nature08300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuerenburg HJ. J Neural Transm. 2000;107:321–329. doi: 10.1007/s007020050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lampl Y, Geva D, Gilad R, Eshel Y, Ronen L, Sarova-Pinhas I. J Neurol. 1998;245:584–588. doi: 10.1007/s004150050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.el-Yazigi A, Martin CR, Siqueira EB. Clin Chem. 1988;34:1084–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melo TM, Larsen C, White LR, Aasly J, Sjobakk TE, Flaten TP, Sonnewald U, Syversen T. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;93:1–8. doi: 10.1385/BTER:93:1-3:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molina JA, Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Aguilar MV, Meseguer I, Mateos-Vega CJ, Gonzalez-Munoz MJ, de Bustos F, Porta J, Orti-Pareja M, Zurdo M, Barrios E, Martinez-Para MC. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:479–488. doi: 10.1007/s007020050071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler H, Pajonk FG, Meisser P, Schneider-Axmann T, Hoffmann KH, Supprian T, Herrmann W, Obeid R, Multhaup G, Falkai P, Bayer TA. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:1763–1769. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dexter DT, Carayon A, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y, Wells FR, Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 4):1953–1975. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.4.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karppanen H. Ann Med. 1991;23:299–305. doi: 10.3109/07853899109148064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altura BM, Altura BT. Cell Mol Biol Res. 1995;41:347–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazard EM. Cal West Med. 1933;39:156–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herz R, Weber A, Reiss I. Biochemistry. 1969;8:2266–2271. doi: 10.1021/bi00834a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alcock N, Macintyre I. Clin Sci. 1964;26:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreland RS, Ford GD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;208:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turlapaty PD, Altura BM. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978;52:421–423. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrier O, Jr, Hester RK, Jurevics HA, Tenner TE., Jr Blood Vessels. 1976;13:321–337. doi: 10.1159/000158103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell WE. Eur J Biochem. 1973;33:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palaty V. J Physiol. 1971;218:353–368. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie CX, Mattson MP, Lovell MA, Yokel RA. Brain Res. 1996;743:271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pratico D, Uryu K, Sung S, Tang S, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. FASEB J. 2002;16:1138–1140. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0012fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bondy SC, Ali SF, Guo-Ross S. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1998;34:219–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02815081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leterrier JF, Langui D, Probst A, Ulrich J. J Neurochem. 1992;58:2060–2070. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin RW, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7221–7233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-07221.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muma NA, Singer SM. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1996;18:679–690. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(96)00126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abreo K, Abreo F, Sella ML, Jain S. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savory J, Rao JK, Huang Y, Letada PR, Herman MM. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:805–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu HJ, Hu QS, Lin ZN, Ren TL, Song H, Cai CK, Dong SZ. Brain Res. 2003;980:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson VJ, Kim SH, Sharma RP. Toxicol Sci. 2005;83:329–339. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hori H, Ohmori O, Shinkai T, Kojima H, Okano C, Suzuki T, Nakamura J. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:170–177. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Son EW, Lee SR, Choi HS, Koo HJ, Huh JE, Kim MH, Pyo S. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30:743–749. doi: 10.1007/BF02977637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarban S, Isikan UE, Kocabey Y, Kocyigit A. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2007;115:97–106. doi: 10.1007/BF02686022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Araya M, Olivares M, Pizarro F, Mendez MA, Gonzalez M, Uauy R. J Nutr. 2005;135:2367–2371. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wakisaka Y, Chu Y, Miller JD, Rosenberg GA, Heistad DD. Stroke. 2010;41:790–797. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shull S, Heintz NH, Periasamy M, Manohar M, Janssen YM, Marsh JP, Mossman BT. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24398–24403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Speich M, Auget JL, Arnaud P. Clin Chem. 1989;35:833–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu Q, Huang K, Xu H. J Inorg Biochem. 2003;94:301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(03)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kryukov GV, Gladyshev VN. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigo R, Gladyshev VN. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gladyshev VN, Kryukov GV, Fomenko DE, Hatfield DL. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:579–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stranges S, Marshall JR, Trevisan M, Natarajan R, Donahue RP, Combs GF, Farinaro E, Clark LC, Reid ME. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:694–699. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rajagopalan KV. Annu Rev Nutr. 1988;8:401–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.08.070188.002153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hassouneh B, Islam M, Nagel T, Pan Q, Merajver SD, Teknos TN. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1039–1045. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Redman BG, Esper P, Pan Q, Dunn RL, Hussain HK, Chenevert T, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1666–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ni Z, Hou S, Barton CH, Vaziri ND. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2329–2336. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Webb RC, Winquist RJ, Victery W, Vander AJ. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:H211–216. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.241.2.H211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Purdy RE, Smith JR, Ding Y, Oveisi F, Vaziri ND, Gonick HC. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee HJ, Lee EY, Kwon MS, Paik YK. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horvatovich P, Hoekman B, Govorukhina N, Bischoff R. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:1421–1437. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garcia A, Prabhakar S, Brock CJ, Pearce AC, Dwek RA, Watson SP, Hebestreit HF, Zitzmann N. Proteomics. 2004;4:656–668. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Issaq HJ. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:3629–3638. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200109)22:17<3629::AID-ELPS3629>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd Dis Markers. 2002;18:99–105. doi: 10.1155/2002/505397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu CC, MacCoss MJ. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2002;4:242–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5:302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dayarathna MK, Hancock WS, Hincapie M. Journal of Separation Science. 2008;31:1156–1166. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whiteaker JR, Zhang H, Eng JK, Fang R, Piening BD, Feng LC, Lorentzen TD, Schoenherr RM, Keane JF, Holzman T, Fitzgibbon M, Lin C, Cooke K, Liu T, Camp DG, 2nd, Anderson L, Watts J, Smith RD, McIntosh MW, Paulovich AG. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:828–836. doi: 10.1021/pr0604920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anspach B, Gierlich HU, Unger KK. J Chromatogr. 1988;443:45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)94781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Doker S, Mounicou S, Dogan M, Lobinski R. Metallomics. 2010;2:549–555. doi: 10.1039/c004508j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lecchi P, Gupte AR, Perez RE, Stockert LV, Abramson FP. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2003;56:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(03)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alvarez-Manilla G, Atwood J, 3rd, Guo Y, Warren NL, Orlando R, Pierce M. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:701–708. doi: 10.1021/pr050275j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Herbert J, Wilcox JN, Pham KT, Fremeau RT, Jr, Zeviani M, Dwork A, Soprano DR, Makover A, Goodman DS, Zimmerman EA, et al. Neurology. 1986;36:900–911. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saraiva MJ. Hum Mutat. 1995;5:191–196. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ellie E, Camou F, Vital A, Rummens C, Grateau G, Delpech M, Valleix S. Neurology. 2001;57:135–137. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seibold S, Rudroff C, Weber M, Galle J, Wanner C, Marx M. FASEB J. 2003;17:1180–1182. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0934fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodrigues-Ferreira S, Di Tommaso A, Dimitrov A, Cazaubon S, Gruel N, Colasson H, Nicolas A, Chaverot N, Molinie V, Reyal F, Sigal-Zafrani B, Terris B, Delattre O, Radvanyi F, Perez F, Vincent-Salomon A, Nahmias C. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Colorado PC, Torre A, Kamphaus G, Maeshima Y, Hopfer H, Takahashi K, Volk R, Zamborsky ED, Herman S, Sarkar PK, Ericksen MB, Dhanabal M, Simons M, Post M, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR, Sukhatme VP, Kalluri R. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2520–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zheng JP, Tang HY, Chen XJ, Yu BF, Xie J, Wu TC. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sudhakar A, Nyberg P, Keshamouni VG, Mannam AP, Li J, Sugimoto H, Cosgrove D, Kalluri R. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2801–2810. doi: 10.1172/JCI24813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 86.Nyberg P, Xie L, Sugimoto H, Colorado P, Sund M, Holthaus K, Sudhakar A, Salo T, Kalluri R. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3292–3305. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shah S, Kumar Y, McLean B, Churchill A, Stoodley N, Rankin J, Rizzu P, van der Knaap M, Jardine P. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010;14:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sibon I, Coupry I, Menegon P, Bouchet JP, Gorry P, Burgelin I, Calvas P, Orignac I, Dousset V, Lacombe D, Orgogozo JM, Arveiler B, Goizet C. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:177–184. doi: 10.1002/ana.21191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gould DB, Phalan FC, van Mil SE, Sundberg JP, Vahedi K, Massin P, Bousser MG, Heutink P, Miner JH, Tournier-Lasserve E, John SW. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1489–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Akerlof E, Jornvall H, Slotte H, Pousette A. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8986–8990. doi: 10.1021/bi00101a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ng DS, Leiter LA, Vezina C, Connelly PW, Hegele RA. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:223–229. doi: 10.1172/JCI116949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nakata K, Kobayashi K, Yanagi H, Shimakura Y, Tsuchiya S, Arinami T, Hamaguchi H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;196:950–955. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Booth SE, Hutton T, Nguyen O, Totty NF, Feest TG, Hsuan JJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7389–7393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Glenn KC, Frost GH, Bergmann JS, Carney DH. Pept Res. 1988;1:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Bautista LE, Sharma P. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1652–1661. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.11.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miyata T, Aruga R, Umeyama H, Bezeaud A, Guillin MC, Iwanaga S. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7457–7462. doi: 10.1021/bi00148a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miyata T, Morita T, Inomoto T, Kawauchi S, Shirakami A, Iwanaga S. Biochemistry. 1987;26:1117–1122. doi: 10.1021/bi00378a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goodfriend TL, Peach MJ. Circ Res. 1975;36:38–48. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.6.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weir MR, Dzau VJ. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:205S–213S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jankowski V, Vanholder R, van der Giet M, Tolle M, Karadogan S, Gobom J, Furkert J, Oksche A, Krause E, Tran TN, Tepel M, Schuchardt M, Schluter H, Wiedon A, Beyermann M, Bader M, Todiras M, Zidek W, Jankowski J. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:297–302. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000253889.09765.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]