Abstract

Human umbilical cord blood (HUCB) cell therapies have shown promising results in reducing brain infarct volume and most importantly in improving neurobehavioral function in rat permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion, a model of stroke. In this study, we examined the gene expression profile in neurons subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) with or without HUCB treatment and identified signaling pathways (Akt/MAPK) important in eliciting HUCB-mediated neuroprotective responses. Gene chip microarray analysis was performed using RNA samples extracted from the neuronal cell cultures from four experimental groups: normoxia, normoxia + HUCB, OGD, and OGD + HUCB. Both quantitative RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry were carried out to verify the microarray results. Using the Genomatix software program, promoter regions of selected genes were compared to reveal common transcription factor-binding sites and, subsequently, signal transduction pathways. Under OGD condition, HUCB cells significantly reduced neuronal loss from 68% to 44% [one-way ANOVA, F(3, 16) = 11, p = 0.0003]. Microarray analysis identified mRNA expression of Prdx5, Vcam1, CCL20, Alcam, and Pax6 as being significantly altered by HUCB cell treatment. Inhibition of the Akt pathway significantly abolished the neuroprotective effect of HUCB cells [one-way ANOVA, F(3, 11) = 8.663, p = 0.0031]. Our observations show that HUCB neuroprotection is dependent on the activation of the Akt signaling pathway that increases transcription of the Prdx5 gene. We concluded that HUCB cell therapy would be a promising treatment for stroke and other forms of brain injury by modifying acute gene expression to promote neural cell protection.

Keywords: Ischemia, Human umbilical cord blood (HUCB), Gene expression, Cell signaling pathways

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the fourth leading cause of death and the leading cause of disability in the US today. Even so, there remains only one available treatment option (76). Inflammation is generally recognized as the major effector in the pathological progression of stroke (11,30,63,66,83), and enormous progress has been made toward identifying the roles of important immune-inflammatory signaling molecules, cells, and proteins in the process of initiation and development of postischemic inflammation (24). Over the past decade, there have been considerable developments in the area of human umbilical cord blood (HUCB) cell research and stem cell transplantation as a therapy for stroke. Intravenous administration of HUCB cells has been shown to exert therapeutic effects in animal models of stroke (12,65,79,82,84) as well as other neurodegenerative diseases (42,56,68). The mechanism underlying the structural and functional improvement and the cellular effects causing the observed benefits are not fully understood (54,78). It is has been shown that these neural cell protective effects of HUCB cells are mediated through releasing trophic factors (13,28,65).

Our laboratory and others have demonstrated the significance of the Akt pathway in eliciting the cellular protection response of HUCB cells to a stressed environment (9,17,18,46). Activation of both MAPK/Erk and Akt is known to be important in cell survival while the Akt pathway was found to be more important in inhibiting apoptosis (48,51,93). When HUCB cells are administered 48 h after a permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), apoptosis is significantly decreased (53). We have shown previously that soluble factors released from HUCB cells induce genes and protein expression that promote cell survival in oligodendrocytes, reduce oxidative stress, and alter inflammatory signaling. These factors converge on Akt phosphorylation to enhance peroxiredoxin 4 (Prx4) protein expression in ischemic white matter (65). The main goal of this study was to identify HUCB-induced neuronal genes associated with cellular survival. We have profiled gene expression in neurons exposed to HUCB treatment subsequent to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) and have determined signaling pathways related to cellular survival. We have utilized both in vitro and in vivo models to examine whether HUCB cells are dependent on Akt/MAPK for their neuroprotective responses. Thus, the results from this study will provide evidence for how soluble factors secreted by HUCB cells induce critical signaling pathways in neurons that result in enhanced cellular survival after ischemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary Neuron Culture

Primary neurons were isolated from E18 Sprague–Dawley rat embryos (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Rat pups were euthanized and were placed in ice-cold isotonic solution [composition (g/L): NaCl, 8; KCl, 0.4; KH2PO4, 0.03; glucose, 0.1; and sucrose, 20.2; in dH2O at pH 7.4; all components from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA]. After removing meninges and blood vessels, brains were placed in an isotonic solution of 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (Cellgro #25-053-CI; Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) at 37ºC for 10 min to disrupt the connective tissue. Trypsinization was then stopped using DMEM complete [DMEM+10% fetal calf serum + antibiotic–antimycotic (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)], and triturated through a fire-polished Pasteur pipette (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) until the solution became much more uniform. Supernatant was aspirated into another tube and centrifuged at 126 × g (1,500 rpm) for 10 min and then resuspended in DMEM complete. The cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 cell/cm2 onto poly-L-lysine-treated (Sigma-Aldrich) 24-well plates (Corning® Life Sciences, Corning, NY, USA). Media was changed to Neurobasal (#21003-049; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with B-27 (#17504-044; Invitrogen) the following day and every second day thereafter for 7 days.

Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Experiment

HUCB Cell Preparation

Just prior to the OGD experiment, cryopreserved HUCB mononuclear cells (AllCells, LLC, Alameda, CA, USA) were thawed in a 37ºC water bath and then washed twice in 10 ml PBS (136.9 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4)/100 μl DNase (1 mg/ml, #D4527-40KU; Sigma-Aldrich). The number of viable cells was determined using the trypan blue exclusion method (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell viability generally ranged from 80% to 90%. Neurons in experimental groups requiring the OGD conditions were cultured either alone or in a coculture with HUCB cells.

OGD

The OGD environment was created by deoxygenated sugar-free medium, Neurobasal-A (#05-0128DJ; Gibco/Invitrogen) bubbling with N2/CO2 (95%/5%; Airgas, Tampa, FL, USA) for 20 min. Media was replaced from cells undergoing OGD with the flashed media. An additional 400 μl of flashed media was added to cell culture inserts (0.2 μm, 10 mm, #136935; Nunc, Penfield, NY, USA) aseptically placed into the plate wells. In the OGD + HUCB group, freshly thawed HUCB cells were added to the top of the insert at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/cm2. The culture plate was then placed in an airtight hypoxic chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA, USA) that was flashed with the 95% N2/5% CO2 gas mixture for 10 min and sealed off from the ambient air. The experiments were conducted in a constant 37ºC environment by placing the chambers in a water-jacketed incubator for 20 h. For inhibition of Akt/MAPK, the same experimental procedures were performed except Akt inhibitor IV (Akti, 1.67 μl/ml, #124011; Calbiochem, Torrey Pines, CA, USA) and MAPK inhibitor U0126 (MAPKi, 1 μl/ml, #9903; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were added to the media. Media with inhibitors (4 ml) was evenly split in the well and the insert.

Fluorescein Diacetate/Propidium Iodide (FDA-PI) Assay

Assay mixture was made by adding 5 μl of FDA stock solution (5 mg/ml in acetone, #F1303; Invitrogen, Fisher Scientific) and 2 μl of PI working solution (0.02 mg/ml in PBS, #P1304MP; Invitrogen). The mixture was added to each well and incubated at 4ºC for 5 min. The cultures were then photographed under an Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope, and the number of living (FDA positive: green) and dead (PI positive: red) cells were counted using Image Pro II software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA). A minimum of five photographs were taken per condition.

RNA Preparation

Cells were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate- buffered saline and lysed with 350 μl of RNeasy Lysis Buffer (#79216; Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Cell lysate was collected and pipetted into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge (#74104; Qiagen) tubes and stored in a −80ºC freezer. RNA was isolated from each sample according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using the RNeasy mini kit (#74104; Qiagen). The RNA samples were then frozen and stored at −80ºC. The RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry (Fisher Scientific) at 260 nm, and the optical density (OD) was determined by the 260/280 ratio. The OD of the RNA was between 1.84 and 2.45. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with an Affinity Script QPCR cDNA Synthesis kit (Cat. No. 600559; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Gene Array

Gene chip microarray analysis was performed by the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center microarray core facility utilizing a GeneChip 3000 Scanner and a GCOS 1.4 with the Affymetrix MAS 5.0 algorithm to generate signal intensities, as well as a GeneChip Rat Genome 230 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Normalized microarray data were populated within a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Redmond, WA, USA), and neuronal gene expression was compared between cultures exposed to HUCB cells in OGD conditions and normoxic conditions. Genes with ≥1.5-fold increases and signal intensities more than 100 were identified for further investigation.

Confirmation of Gene Changes by Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR)

When expression increased by ≥1.5-fold in the HUCB-treated cells, we confirmed gene expression using RT-PCR. In this study, the profiled genes included genes known to be associated with inflammation and the immune response. All primers were purchased from SABioscience (Frederick, MD; sequences are proprietary). They were glycine receptor, β subunit (Glrb); cytochrome p450, family 3, subfamily a, polypeptide 23/polypeptide 1 (Cyp3a23/3a1); peroxiredoxin 5 (Prdx5); protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, O (Ptpro); chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2); chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20; vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (Vcam1); activating transcription factor 2 (Atf2); myotrophin (Mtpn); protein phosphatase 3, catalytic subunit, β isoform (Ppp3cb); glutaredoxin 1 (Glrx1); kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1); contactin 4 (Cntn4); doublecortin (Dcx); thymoma viral proto-oncogene 3 (Akt3); activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (Alcam); olfactomedin 3 (Olfm3); chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1; melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha); paired box 6 (Pax6); doublecortin-like kinase 1 (Dclk1); protein phosphatase 3, regulatory subunit B, α isoform (calcineurin B, type I; Ppp3r1); neuronal growth regulator 1 (Negr1), and stathmin-like 4 (Stmn4). Briefly, total RNA (20 ng/μl) from each sample was reserve transcribed in the presence of poly(dT) sequences. Reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μl containing 3 μl Oligo (dT) primers, 10 μl of cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (2×), 1 μl of Affinity Script RT/Rnase block enzyme mixture (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the balance RNAse-free H2O obtained from SABioscience (Frederick, MD, USA) and Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralvile, IA, USA). The amplification was carried out using the following cyclic parameters: 1) 5-min incubation at 25ºC for primer annealing; 2) 15 min at 42ºC for cDNA synthesis; and 3) 5 min at 95ºC to terminate the cDNA synthesis reaction (AffinityScript QPCR cDNA Synthesis Kit). Each PCR experimental reaction (25 μl) contained 1 μl of cDNA synthesis, 12.5 μl of Sybr Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene), and 2 μl of forward and reverse primers. The amplification protocol consisted of one cycle of 15 min at 95ºC; 40 cycles of 30 s at 55ºC; and one cycle of 30 s at 72ºC. Data were expressed as a function of the threshold cycle (Ct). The formula used to calculate the relative gene expression level was: Δ CT = CT(GOI) - avg.(CT(HKG)), where GOI is each gene of interest, and HKG is the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH). Changes in gene expression were expressed as a fold increase/decrease. The threshold for qualification as expression-determining induction was a 1.5-fold change. Genes that met the above criteria were further categorized as either upregulated or downregulated. Experiments were performed in duplicate.

Promoter Analysis–Transcription Factor Binding Sites

Accession numbers for the mRNA sequences of genes induced by HUCB cells were imported into the Genomatix software (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) program. The promoter sequences of the genes were then retrieved using the Genomatix Gene2Promoter program. Promoter regions common in selected genes were identified and further analyzed for common transcription factor binding sites (TFBS).

Animal Housing and Maintenance

A total of 10 adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 5 per control or HUCB-treated group; Harlan Laboratories) were kept in continuous 12-h dark/light cycles in a temperature-controlled room with water and chow ad libidum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the recommendations in the guide for the use of experimental animals from the National Institutes of Health. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine.

MCAO Surgery and HUCB Injection

MCAO surgeries were performed as described previously (78). Briefly, the common carotid artery was carefully isolated from the vagus nerve. Two closely spaced permanent knots were placed at the distal part of the ECA and incised using microscissors. A filament was inserted through the ECA into the internal carotid artery and advanced carefully to the origin of the middle cerebral artery. Afterward, the monofilament was ligated permanently, and the neck incision was closed using surgical suture. HUCB cells were thawed rapidly at 37ºC and transferred slowly into 10 ml of PBS with 100 μl DNase (1 mg/ml, #D4527-40KU; Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were then centrifuged for 10 min at 200 × g, and the supernatant was removed. The trypan blue dye exclusion method was used in order to determine the number of viable cells (Sigma-Aldrich). Rats were injected with 1 × 106 HUCB cells in a volume of 500 μl of PBS through the penile vein 48 h after the MCAO surgery.

Immunohistochemistry

Following OGD, cells were washed several times with PBS and fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific). Cells were then incubated in 5% donkey serum (LAMPIRE Biological Laboratories, Inc., Ottsville, PA, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween®-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h to permeabilize the cells and block nonspecific protein. The cells were then incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies including phospho-Akt (1:200; Cell Signaling) and mouse monoclonal anti-peroxiredoxin 5 (Prdx5) (1:80; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4ºC. The secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor® 488 donkey anti-rabbit (green) and Alexa Fluor® 594 (red) donkey anti-mouse (Invitrogen) were used at a 1:1,000 dilution for 1 h. DAPI was used to stain the cell nuclei (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Rats were perfused transcardially with 0.1 M PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 24 h and then equilibrated in 30% sucrose for an additional 24 h. Brains were cut into 30-μm coronal sections using a Micro cryostat (Hacker Instruments & Industries, Inc., Winnsboro, SC, USA) and mounted on slides. Several rinses in PBS were followed by incubation in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich)/3% normal goat serum (LAMPIRE Biological Laboratories, Inc.) for 1 h and incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies anti-Prdx5 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-Cxcl1 (1:250, #AF-515-NA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in PBS at 4ºC. The following day slides were washed and incubated for 1 h in biotinylated goat anti-rat antibody (1:500; Invitrogen), then washed 3 × 10 min before 1 h incubation in avidin–biotin complex (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Then slides were incubated in DAB (diaminobenzidine; Fisher Scientific) solution for 2–10 min. Slides were then dried, dehydrated through a graded alcohol series into xylene, and coverslipped with Permount mounting medium (360294H; BDH/VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). Five images in the region around the ischemic core in the ipsilateral hemisphere and the corresponding fields from the contralateral hemisphere were captured using an Olympus IX71 microscope, and positive staining was counted using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. The cell culture survival, microarray, and Prdx5 immunolabeling studies were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. The in vivo studies were analyzed with Students’ t-test for independent samples to assess significance. Alpha levels were set at 0.05 for all analyses. The GraphPad Prism 5.01 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all data analysis.

RESULTS

Coculturing HUCB Cells Rescued Neuronal Loss Following OGD

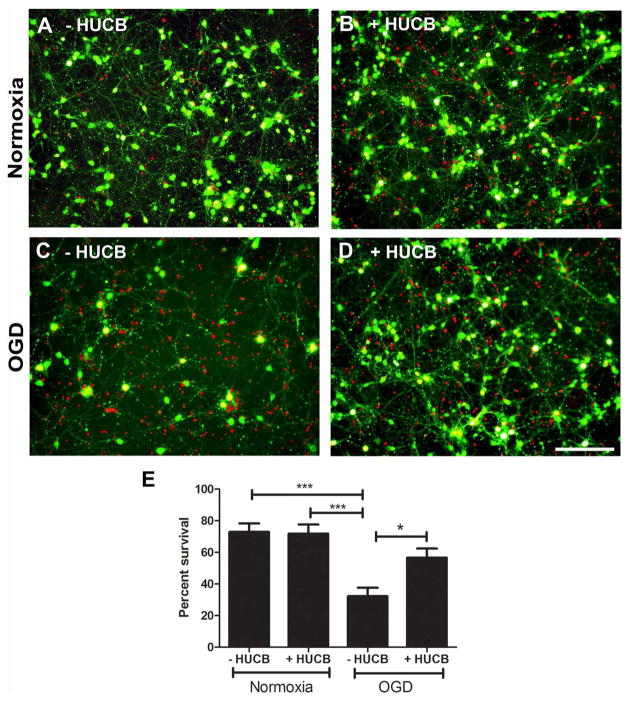

Primary cortical neuron cultures obtained from E18 Sprague–Dawley rat embryos were exposed to either 20 h of normoxic or OGD conditions in the presence or absence of HUCB cells (Fig. 1). Survival of neurons cocultured with HUCB cells under normoxic conditions was not different from neurons cultured alone (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1A, B, E). OGD induced neuronal loss (Fig. 1C). When the number of living and dead cells were quantified in each condition, there were significant differences between the groups [F(3, 16) = 11, p = 0.0003] (Fig. 1C, E). Under OGD conditions, HUCB cells significantly rescued neuronal loss (cell viability = 56 ± 6.45%) (Fig. 1D, E) compared to cultures of neurons alone (cell viability = 31 ± 6.07%) (p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

HUCB cells rescued neurons from OGD. There was no significant difference in cell viability determined using the FDA-PI assay in cultures exposed to normoxia in the absence (A) or presence of HUCB cells (B). There were more dead cells (red, PI) in the culture exposed to OGD in the absence of HUCB cells (C). Conversely, there were more viable cells (green, FDA) in the culture exposed to OGD treated with HUCB cells (D). (E) The percent survival of neurons exposed to either normoxia or OGD conditions for 20 h assessed by FDA-PI staining (***p < 0.0001, OGD vs. normoxic conditions; *p < 0.05, OGD vs. OGD + HUCB). Scale bar: 100 μM.

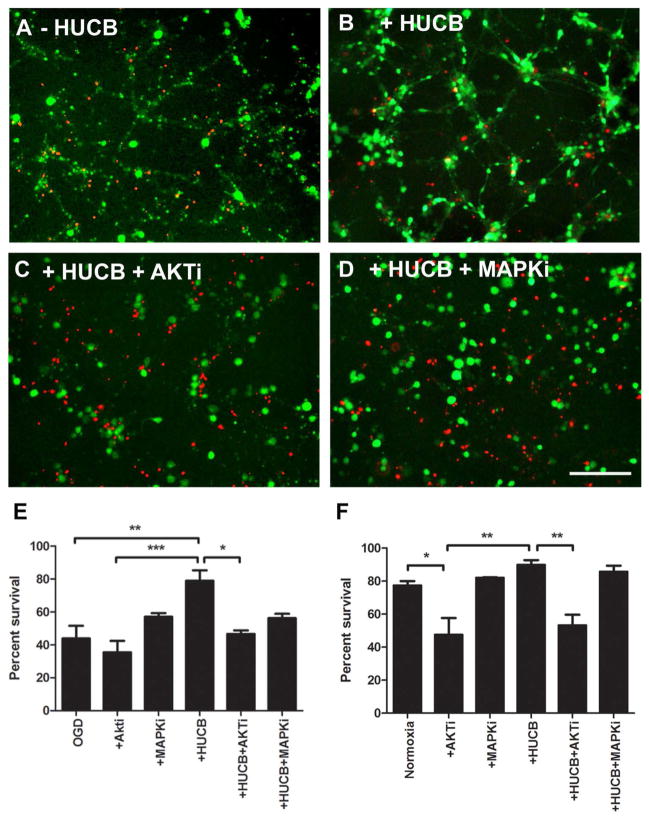

Blocking Akt Activity Prevents HUCB-Induced Neuronal Protection After OGD

We also examined in culture whether the neuroprotective effects of HUCB cells could be blocked by inhibiting Akt or MAPK signal transduction pathways by comparing neuronal cell viability after OGD, OGD with HUCB cells, OGD with HUCB cells and Akt inhibitor, and OGD with HUCB cells and MAPK inhibitor (Fig. 2). Cell viability between these four groups differed significantly [F(3, 11) = 8.663, p = 0.0031]. As expected, a significant loss of neurons was observed after exposure to OGD for 20 h (Fig. 2A). HUCB treatment significantly improved the survival of neurons compared with neurons exposed to OGD (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B, E). Interestingly, inhibition of the Akt pathway led to an extensive neuronal death even in the presence of HUCB cells (Fig. 2C, E), but Akt inhibitor administered in conjunction with OGD did not decrease cell survival over that observed with just OGD alone. We also replicated the study under normoxic conditions (Fig. 2F). Under these culture conditions, Akt inhibition significantly decreased neuronal survival from 77.4 ± 2.8 in the untreated culture to 47.5 ± 1.9 (p < 0.05). While HUCB cells did not significantly increase cell survival compared to the untreated cultures (89.9 ± 1.6), cell survival significantly decreased when Akti was added to the neuron–HUCB cell coculture (53.2 ± 3.3, p < 0.01), which was similar to survival in the Akti-only group. These results demonstrate that the Akt pathway has an important role in OGD conditions, and it may be the major pathway of HUCB-mediated neuroprotection in the OGD condition.

Figure 2.

HUCB cell-mediated neuroprotection depends on activation of the Akt signaling pathway. Significant neuronal loss was observed in neurons exposed to OGD (A). HUCB cell treatment rescued neuronal loss (B), while HUCB cells lose their neuroprotective effects after adding Akt inhibitor (Akti; Akt inhibitor IV) into the culture media (C). Addition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor (MAPKi; MAPK inhibitor U0126) failed to influence HUCB cell-mediated neuronal protection (D). When the percent survival of neurons under OGD conditions was calculated (E), Akt and MAPK inhibitors did not alter survival compared to OGD alone, but HUCB cells significantly increased survival. Akt inhibitor added to neuronal–HUCB cell cocultures significantly decreased cell survival. In normoxic cultures (F), the Akt inhibitor decreased cell survival in neuronal cultures with and without HUCB cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Scale bar: 100 μm.

In contrast to Akt inhibition, MAPK inhibition had no significant effect on neuronal survival in normoxic or OGD conditions (Fig. 2D–F).

HUCB in Neuronal Cultures Induced the Expression of Genes Related to the Immune-Inflammatory Response

Microarray analysis was performed to evaluate changes in gene expression following OGD exposure. Under normoxic conditions, 64 genes were found to be induced by the presence of HUCB cells; these genes are known to be important in the detoxification, immunogenic, cell trafficking, and signaling pathways (Table 1). Thirteen genes were identified as transcription factors associated with growth factor signaling, particularly nerve growth factor (NGF). The signaling group also contained a number of cell survival-related genes. In OGD conditions, 84 genes were found to be induced in neurons in the presence of HUCB cells. The groupings of these genes and individual genes deviated from those detected in the normoxia experiment. In fact, only one gene, myotropin, appeared on both lists. Genes related to detoxification and signaling were those with the greatest changes in the OGD group.

Table 1.

Genes Induced >1.5-Fold Increase in Neurons After HUCB Cell Treatment

| Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | Alcam | 1.51 |

| Activating transcription factor 2 | Atf2 | 2.32 |

| Apoptotic peptidase-activating factor 1 | Apaf1 | 3.03 |

| Cartilage acidic protein 1 | Crtac1 | 4.79 |

| Caspase 3, apoptosis-related cysteine protease | Casp3 | 2.49 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | Ccl2 | 2.28 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 | Ccl20 | 96.53 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | Cxcl1 | 1.84 |

| Chromogranin B | Chgb | 1.95 |

| Cold shock domain-containing E1, RNA-binding | Csde1 | 1.87 |

| Contactin 4 | Cntn4 | 10.94 |

| Corticotrophin releasing hormone-binding protein | Crhbp | 5.09 |

| Cytochrome P450, family 3 | Cyp3a23/3a1 | 125.36 |

| Doublecortin | Dcx | 1.86 |

| Glutaredoxin 1 (thioltransferase) | Glrx1 | 1.88 |

| Glycine receptor, α 2 subunit | Glra2 | 4.60 |

| Glycine receptor, β subunit | Glrb | 3.47 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α inhibiting 1 | Gnai1 | 1.49 |

| Kelch-like ECH-associated oriteub 1 | Keap1 | 6.57 |

| Muscle and microspikes RAS | Mras | 2.57 |

| Myotrophin | Mtpn | 1.97 |

| Natriuretic peptide receptor 3 | Npr3 | 34.49 |

| Neuronal growth regulator 1 | Negr1 | 1.87 |

| Olfactomedin 3 | Olfm3 | 2.54 |

| Opioid binding protein/cell adhesion molecule-like | Opcm1 | 2.10 |

| Peroxiredoxin 5 | Prdx5 | 1.75 |

| Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 1 | Prps1 | 2.16 |

| Protein kinase, cAMP-dependent, regulatory, type 2, α | Prkar2a | 1.96 |

| Protein phosphatase 3, catalytic subunit, β isoform | Ppp3cb | 1.66 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, O | Ptpro | 1.75 |

| Reticulon 3 | Rtn3 | 3.09 |

| Stathmin-like 4 | Stmn4 | 1.51 |

| Stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 2 | Scd2 | 1.86 |

| Thymoma viral proto-oncogene 3 | Akt3 | 1.80 |

| Tropomyosin 1, α | Tpm1 | 1.50 |

| UDP galactosyltransferase 8A | Ugt8a | 6.82 |

| Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | VCAM1 | 1.60 |

| Zinc finger protein 111 | Zfp111 | 2.66 |

qRT-PCR Confirms the Immune-Inflammatory Gene Expression in Neurons In Vitro

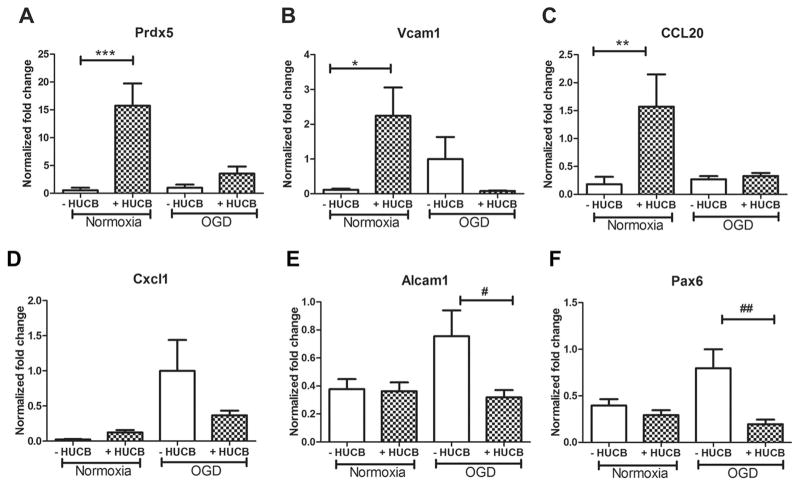

The 23 genes selected for confirmation by qRT-PCR were Glrb, Cyp3A23/3a1, Prdx5, Ptpro, CCL2, CCL20, Vcam1, Atf2, Mtpn, Ppp3r1, Glrx1, Keap1, Cntn4, Dcx, Akt3, Alcam1, Olfm3, Cxcl1, Pax6, Dclk1, Ppp3r1, Negr1, and Stmn4. When different treatment groups were normalized to OGD, Prdx5, Vcam1, and CCL20 were significantly induced in neurons treated with HUCB cells under normoxic conditions (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3A–C). There were no significant differences in expression of these three factors between the OGD HUCB-treated group compared to the OGD-alone groups (p > 0.05). Under OGD conditions, Cxcl1, Alcam1, and Pax6 tended to be increased compared to normoxia. HUCB cells significantly decreased expression of Alcam1 and Pax6 genes that were increased by OGD alone (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3E, F). Although expression of Cxcl1 was not statistically significant, there was a tendency for decreased expression of Cxcl1 in neurons treated with HUCB under OGD condition (Fig. 3D). HUCB induced expression of other genes, including Ptpro, Cntn4, and Glrb, both under normoxic and OGD conditions and decreased expression of Keap1; these results also failed to reach a statistically significant level.

Figure 3.

The effects of HUCB cell treatment on gene expression in neurons. Under normoxic conditions, HUCB cells significantly upregulated gene expression of (A) peroxiredoxin 5 (Prdx5; ***p < 0.001), (B) vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (Vcam1; *p < 0.05), and (C) chemokine C-C motif ligand 20 (CCL20; **p < 0.01) compared to normoxic cultures alone. Under OGD conditions, HUCB cells appeared to downregulate gene expression of (E) activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (Alcam1; #p < 0.05) and (F) paired box 6 (Pax6; ##p < 0.01) compared to OGD alone. There was a tendency to decrease expression of chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 1 (CXCL1) (D), but it did not reach significance. The results are expressed as mean fold change ± SEM.

Common Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBSs) Were Identified in HUCB-Treated Neurons

Gene expression is mediated by transcription factors, and a single transcription factor frequently binds regulatory regions of different genes (19,41). To identify shared TFBSs, the promoter region of genes altered in neuron coculturing with HUCB cells subsequent to OGD were analyzed by Genomatix software. The following common TFBSs were identified: heat shock factor 1(Hsf1), myeloid zinc finger protein (MZF1), zinc finger transcription factor (MyT1), cut-like homeodomain protein (Cux1), T-cell-specific transcription factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (TCF/LEF-1), and nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 (Nfat5); most of these TFBSs are involved in protective mechanisms against the deleterious consequences of ischemia-induced oxidative stress. These results indicate that genes upregulated by HUCB following OGD share this common signaling pathway (Table 2).

Table 2.

Transcriptional Factor Binding Sites Within the Promoter Regions Shared by HUCB Cell-Induced Genes

| Family | Matrix | Transcription Factor |

|---|---|---|

| V$CLOX | V$CLOX.01 | Cut-like homeodomain protein |

| V$RUSH | V$SMARCA 3.01 | SWI/SNF related proteins |

| V$PARF | V$TEF_HLF.01 | Thyrotrophic embryonic factor/hepatic leukemia factor |

| V$NFAT | V$NFAT5.01 | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 |

| V$MZF1 | V$MZF1.02 | Myeloid zinc finger protein MZF1 |

| V$MYT1 | V$MYT1.01 | MyT1 zinc finger transcription factor |

| V$LEFF | V$LEF1.01 | TCF/LEF-1 |

| V$HEAT | V$HSF1.01 | Heat shock factor 1 |

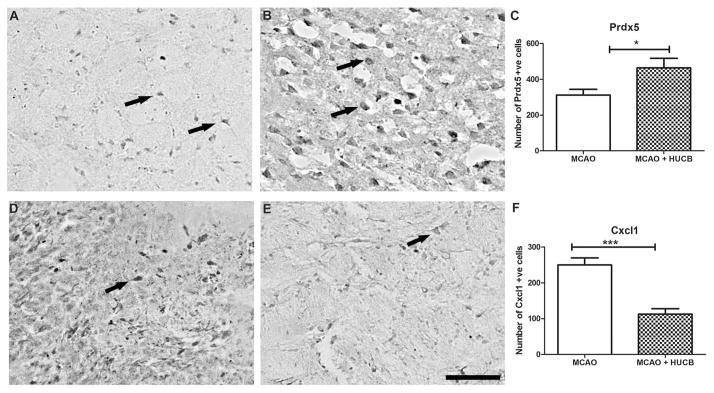

Protein Expression of Genes Modulated by HUCB Cells In Vitro Is Altered in Rat Brain After MCAO

While the changes in gene expression in vitro are suggestive of what is likely to occur in vivo, the simplified nature of the in vitro model system may not accurately reflect gene and protein expression in vivo. For that reason, we performed an additional study in the rat permanent MCAO model of stroke to determine if protein expression of two of the identified factors (Prdx5 and Cxcl1) changed after treatment with HUCB cells. A total of 10 rats (n = 5 per group) were used for this experiment. Immunostaining of rat brain sections for Prdx5 and Cxcl1 was performed subsequent to MCAO and HUCB cell treatment to determine protein expression. After MCAO, Prdx5-positive cells were present in the infarcted hemisphere (Fig. 4A). Rats treated with HUCB cells 48 h after MCAO demonstrated a significant increase in the number of Prdx5-positive cells (Fig. 4B, C). In contrast, there were many Cxcl1-positive cells around the infarct after MCAO (Fig. 4D), and HUCB treatment significantly reduced expression of this chemokine (Fig. 4E, F) in the ipsilateral hemisphere. Immunoreactivity was localized predominantly in the ipsilateral hemisphere. Five fields around the infarct core and corresponding hemisphere were randomly chosen, and the average positive staining was quantified using ImageJ software.

Figure 4.

Gene expression changes in the ipsilateral brain hemisphere from rats treated with HUCB cells 48 h after MCAO. HUCB cells induced Prdx5 protein (B, C) and reduced Cxcl1 (E, F) expression in the rat ipsilateral hemisphere compared to nontreated animals (A, D). Arrows indicate representative examples of positively labeled cells. Bar graphs show quantitative evaluation of Prdx5 (C) and Cxcl1 (F) expression. The results were expressed as mean number of positive cells ± SEM. *p < 0.05 compared with control group. Scale bar: 50 μm.

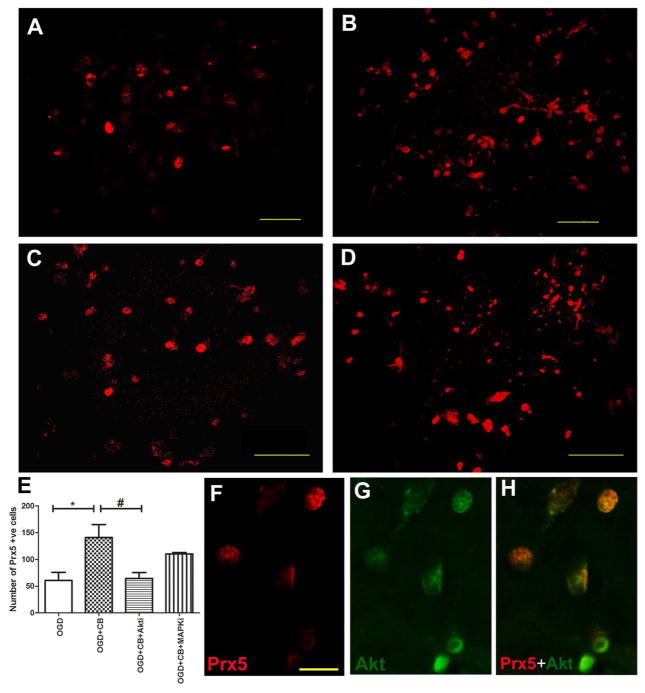

Upregulation of Prdx5 in the Neurons by HUCB After OGD Was Linked With Akt Signaling Pathway

To further investigate the molecular mechanism of HUCB cells on neuronal survival, we investigated the role of Akt or MAPK signaling pathways for the induction of Prdx5 by HUCB cells. The Akt pathway inhibitor IV and MAPK pathway inhibitor U0126 were used to confirm our results. We found that HUCB cells induced Prdx5 expression in the neurons after OGD, and blockade of the Akt pathway significantly reduced HUCB-mediated Prdx5 induction [F(3, 11) = 6.4, p = 0.0163] (Fig. 5). On the other hand, blocking the MAPK pathway had no influence on HUCB-mediated Prdx5 induction. Confocal images revealed that HUCB induced expression of phospho-Akt in neurons after OGD, which was colocalized with Prdx5 protein (Fig. 5F–H). Thus, neurons containing phospho-Akt colocalization with Prdx5 suggest that activation of this kinase increased transcription of the Prdx5 gene. These results suggested that PI3K/Akt pathway is involved in HUCB-induced neuronal survival.

Figure 5.

The Akt pathway plays a significant role in HUCB-mediated neuronal survival. In vitro expression of Prdx5 (abbreviated to Prx5 in figure) in neurons following OGD (A), OGD +HUCB (B), OGD + HUCB +Akti (C), and OGD + HUCB + MAPKi (D). There are significantly more Prdx5-positive cells in neurons following OGD alone and cocultured with HUCB, while inhibition of Akt negates the effects of HUCB [one-way ANOVA, F(3, 11) = 6.4, p = 0.0163]. Graphical representation of the number of Prdx5-positive neurons after HUCB treatment subsequent to OGD (E). Data are presented as mean Prdx5-positive cells ± SEM. *p < 0.5 OGD versus OGD + HUCB, #p < 0.05 OGD + HUCB versus OGD + HUCB +Akti. Confocal images showing Prdx5 colocalized with Akt (F–H). Scale bar: 50 μm (A–D); scale bar: 20 μm (F–H).

DISCUSSION

It has been shown extensively that cerebral ischemia alters gene expression (27,32,36). We have determined that HUCB cells confer neuroprotection by modification of the neuronal gene expression profile. Genes involved in the inflammatory response were significantly altered by HUCB treatment, including Prdx5, Vcam1, CCL20, Alcam1, and Pax6. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway plays a critical role in HUCB-mediated neuroprotection in both the in vitro OGD model and the in vivo rat stroke model. We observed that inhibition of Akt significantly abolished the neuroprotective effect of HUCB, while inhibition of the MAPK failed to exert any significant influence. Also, the presence of HUCB cells induced the antioxidant Prdx5 protein in neurons, and this was dependent on Akt activity. Thus, our results reveal the key mediators within the signaling cascade and genomic effectors of neuroprotection by HUCB cells, which provides insight into novel therapeutic strategies for stroke and other forms of brain injury.

Our main goal with this study was to identify the signaling pathways in neurons following cerebral ischemia that are modulated by the HUCB cells. Our group previously showed that the presence of HUCB cells promotes the expression of myelin-associated and antioxidant genes in cultured primary oligodendrocytes exposed to OGD (64). Subsequent study has extended this basic finding, showing that soluble factors released from HUCB cells increased Prx4 expression, thereby protecting oligodendrocytes through Akt signal transduction (64). Here we utilized both in vitro and in vivo models of stroke to determine whether the activation of Akt kinase is a pivotal transducer in HUCB-induced neuronal protection following ischemia. The roles of the Akt and MAPK signaling pathways on neuronal survival have been investigated extensively (20,26,34,40). The levels of both kinases increased within 1 to 3 h poststroke with a peak at 1 h (43). As levels of Akt and MAPK were decreased by 24 h after MCAO, a valid approach for stroke treatment would be to extend their activation beyond 24 h with HUCB cell administration. Our observations in this study indicated that soluble factors released from HUCB cells facilitated protection from hypoxia-induced cell death in rat primary cortical neurons. This is consistent with our previous work in which we showed that the HUCB cells produce a myriad of growth factors including the neurotrophin nerve growth factor β (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and neurotrophin 3, as well as ciliary neurotropic factor, platelet-derived growth factor BB, vascular endothelial growth factor, stromal-derived growth factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (13). Other research groups have confirmed that the cells produce NGF (8) as well as fibro-blast growth factor 2 (3) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (35,69,90). The effects of many of these neurotrophins and growth factors are mediated by the Akt signaling pathway (33,44,67,72,88,89,91).

The nervous system is more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of free oxygen radicals and other reactive oxygen species than other organ systems; moreover, the brain is relatively deficient in antioxidant species, with lower activity of glutathione peroxidase in comparison with other organs (25,70). Extensive evidence from experimental studies supports a crucial role of free radicals and the protective role of the peroxiredoxin family in the pathogenesis of stroke (15,52,87) and other neurological disorders involving oxidative and inflammatory stress (6,39,92). Prdx5 is an antioxidant enzyme expressed in the cytosol, mitochondria, nuclei, and peroxisomes whose primary function is the reduction of hydrogen peroxide (5,37,92). Recent evidence supports a significant role of Prdx5 in the regulation of mitochondrial ion transport and the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis (38), microglial activation through modulation of ROS/NO generation and activation of JNK signaling (73). The knockdown of Prdx5 accelerates microglial activation leading to increased production of ROS. Systemic administration of recombinant Prdx5 provided protection against ibotenate-induced excitotoxic stress and reduced the brain infarction in newborn mice (59). One study showed that infarct volume and neurological recovery strongly correlates with the low plasma antioxidant activity in stroke (75). In fact, stroke severity appears linked to the antioxidant activity of plasma. One report found that Prdx5 concentrations were lower in patients with more severe strokes and inversely correlated to biomarkers of systemic inflammation (39). This finding implies that Prdx5 is either degraded or its production is impaired in severe stroke. In our study, we found a significant increase in Prdx5 expression in HUCB cell-treated neurons in comparison with the nontreated group under normoxic conditions in vitro and after MCAO in vivo. These differences in results between the different model systems highlight the necessity of verifying cell culture studies in the whole animal.

Oxidative stress reduces phosphorylation of Akt in neurons, while neuroprotective substances increase Akt phosphorylation (85). Akt phosphorylation also protects astrocytes (21) and oligodendrocytes (2) from oxidative stress-induced cell death. It has been reported that Akt maintains Prdx activity by phosphorylating FOXO and preventing transcription of Prdx inhibitors (47). Also, the MAPK pathway plays a significant role in expression of Prdx5 in activated macrophages stimulated by IFN-γ or by LPS (1). Thus, Prdx5 may constitute an important component of the antioxidant effect of HUCB cells and may be a candidate for therapeutic targeting of oxidative stress in stroke. This is consistent with the work of Arien-Zakay et al., who found a 95% decrease in free radicals in a neuronal culture treated with HUCB cells (3).

Further, we have observed genes associated with angiogenesis, such as Vcam1, induced by HUCB cell treatment. An increased blood flow in the ischemic area within a few days after stroke has been reported, suggesting that angiogenesis occurs and may be crucial for neurological recovery. It was demonstrated that interaction of the leukocyte with very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) of Vcam1 is crucial for cerebral extravasation of lymphocytes (58). Recently, it was reported that inhibition of the VLA-4–Vcam1 axis by gene silencing of the VLA-4 reduced infarct volume and postischemic neuroinflammation (45). However, it was previously reported that there was no beneficial effects of blocking Vcam1 in protecting ischemic damage in both rats and mice (31), suggesting Vcam1 induction is not sufficient to induce T-cell trafficking into the brain parenchyma. Overexpression of Vcam1 may recruit leukocytes to the ischemic region and enhance inflammation, which always accompanies angiogenesis (86). A study that investigated the regulation of endothelial adhesion molecules found that Vcam1 expression was regulated through a negative regulation of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/GATA-6 pathway (77). Further, it was reported that rapamycin reduced endothelial expression of TNF-induced Vcam1 through activation of the MAPK pathway (81). Thus, HUCB-induced Vcam1 may be the key coordinator to organize inflammation and angiogenesis in the ischemic organ through recruiting inflammatory cells (13).

Chemokine synthesis subsequent to acute brain injury presents a novel target for anti-inflammatory treatment. Stroke elicits a peripheral immune response, which is likely also a useful target for anti-inflammatory factors induced by HUCB cells. Cxcl1/CINC-1/GRO-1, the rat equivalent of human interleukin-8 (IL-8), acts as a neutrophil chemoattractant and plays a role in the acute phase inflammatory response. It has previously been shown that IL-8 increases in the striatal, hippocampal, and frontal cortex of ischemic rat brain, peaking at 24–72 h postischemia compared with nonstroked tissue (55). In this study, we observed a significant reduction of Cxcl1 reduction in the rat brain treated with HUCB cells after MCAO. High levels of Cxcl1 accumulate in the brain of activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes, which can contribute to tissue damage by physically obstructing vessels and by releasing various bioactive mediators (80). Alcam1, also referred to as CD166, is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) and attracts and recruits leukocytes into the site of inflammation. Alcam1 is widely expressed in various cells, including neurons, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, lymphoid, and myeloid cells (74). Alcam1 is upregulated during neuroinflammation and replaces Vcam1 during transmigration of leukocytes across central nervous system endothelium (10). It was recently reported that there was increased long-term mortality in patients with high levels of Alcam1 at admission for acute ischemic stroke (71), which therefore could be a potential prognostic biomarker for acute ischemic stroke (57). Here we found a decreased expression of Alcam1 in the rat cortical cells treated with HUCB cells in an OGD model.

In this study, we have also analyzed the promoter regions of the genes induced by HUCB cells; we found common TFBSs, including Hsf1, MZF1, Cux1, Nfat5, and TCF/LEF-1. Determination of TFBS is important in order to identify key transcription factors and their corresponding intracellular signaling pathways. Hsf1, a molecular chaperone, regulates the synthesis of heat shock proteins (HSP), has specialized functions in protective mechanisms against deleterious consequences of oxidative stress (16,22). Cerebral ischemia induces formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing intracellular protein aggregation (14). It has been demonstrated that adenoviral-mediated gene transfer for major HSP70 over-expression reduces cerebral infarction by preventing intra-cellular proteins from denaturation that occur in response to oxidative stress (16,61). The zinc finger protein, MZF1, is a regulator protein that plays a crucial role in cell proliferation (23). MZF1 was also identified as a transcription-regulating gene induced in oligodendrocytes exposed to HUCB and OGD (64). MZF1 has been shown to increase FGF-2 protein expression in astrocytes (49). It has not been determined if oxidative stress modulates Cux1 expression; however, in pancreatic cancer cells, Akt induces Cux1 expression, decreasing apoptosis and increasing tumor growth (62). NFAT expression is increased in response to metal-induced generation of ROS (29). Thus, soluble factors from HUCB cells likely protect neurons by limiting oxidative damage. While not all these transcription factors are usually considered downstream targets of Akt, Akt can interact with most of them. For example, the common pathway of NFAT activation is through calcium and calcineurin signaling. However, NFAT is also targeted by the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Indeed, GSK-3β inhibition activates NFAT (60), TCF/Lef-1 (50), and Hsf1(4,7). GSK-3β is a downstream target of Akt. As such, Akt inhibits GSK-3β with the end result being activation of these transcription factors. Thus, clinical manipulation of the signaling pathways of HUCB cell-mediated neuroprotection may lead to therapeutic improvements to prevent or reduce the incidence of cerebral ischemia.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates that HUCB cells rescued neuronal loss after OGD via increasing transcription of genes related to survival and repair and inhibiting those related to cellular death and inflammation. These neuroprotective effects are mediated through the release of soluble factors from HUCB cells. The neurosurvival action of the secretants is transduced through Akt signaling to ramp up transcription of Prdx5 and other survival-associated genes while inhibiting genes such as Cxc11 that play a detrimental role in ischemic injury. Overall, the combined sources of evidence in this study suggest that HUCB cells exert their anti-inflammatory effects in stroke via the suppression of the induced peripheral inflammatory response and play a critical role maintaining blood–brain barrier function and leucocyte trafficking into the cerebral microvasculature. The mechanisms through which these genes prevent cell death could be a key etiological factor common to many neurodegenerative conditions, providing a simple and unifying concept to explain ischemic events in the brain.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the NINDS (RO1NS52839) to A.E.W. A.E.W. is a consultant and P.R.S. a cofounder of Saneron CCEL Therapeutics, Inc. A.E.W. and P.R.S. are inventors on multiple cord blood patents licensed to Saneron CCEL Therapeutics, Inc.

References

- 1.Abbas K, Breton J, Picot CR, Quesniaux V, Bouton C, Drapier JC. Signaling events leading to peroxiredoxin 5 up-regulation in immunostimulated macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(6):794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai K, Lo EH. Astrocytes protect oligodendrocyte precursor cells via MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(4):785–763. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arien-Zakay H, Lecht S, Bercu MMM, Tabakman R, Kohen R, Galski H, Nagler A, Lazarovici P. Neuroprotection by cord blood neural progenitors involves antioxidants, neurotrophic and angiogenic factors. Exp Neurol. 2009;216:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee MS, Chakraborty PK, Raha S. Modulation of Akt and ERK1/2 pathways by resveratrol in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cells results in the down-regulation of Hsp70. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banmeyer I, Marchand C, Clippe A, Knoops B. Human mitochondrial peroxiredoxin 5 protects from mitochondrial DNA damages induced by hydrogen peroxide. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(11):2327–2333. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell KF, Hardingham GE. CNS peroxiredoxins and their regulation in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14(8):1467–1477. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijur GN, Jope RS. Opposing actions of phosphati-dylinositol 3-kinase and glycogen synthase kinase-3-beta in the regulation of HSF-1 activity. J Neurochem. 2000;75(6):2401–2408. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracci-Laudiero L, Celestino D, Starace G, Antonelli A, Lambiase A, Procoli A, Rumi C, Lai M, Picardi A, Ballatore G, Bonini S, Aloe L. CD34-positive cells in human umbilical cord blood express nerve growth factor and its specific receptor TrkA. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;136(1–2):130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calatrava-Ferreras L, Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Herranz AS, Reimers D, Montero Vega T, Jimenez-Escrig A, Richart Lopez LA, Bazan E. Effects of intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood stem cells in 3-acetylpyridine-lesioned rats. Stem Cells Int. 2012:135187. doi: 10.1155/2012/135187. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cayrol R, Wosik K, Berard JL, Dodelet-Devillers A, Ifergan I, Kebir H, Haqqani AS, Kreymborg K, Krug S, Moumdjian R, Bouthillier A, Becher B, Arbour N, David S, Stanimirovic D, Prat A. Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule promotes leukocyte trafficking into the central nervous system. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(2):137–145. doi: 10.1038/ni1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamorro A, Hallenbeck J. The harms and benefits of inflammatory and immune responses in vascular disease. Stroke. 2006;37(2):291–293. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000200561.69611.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Sanberg PR, Li Y, Wang L, Lu M, Willing AE, Sanchez-Ramos J, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood reduces behavioral deficits after stroke in rats. Stroke. 2001;32(11):2682–2688. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.098367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen N, Newcomb J, Garbuzova-Davis S, Davis Sanberg C, Sanberg PR, Willing AE. Human umbilical cord blood cells have trophic effects on young and aging hippocampal neurons in vitro. Aging Dis. 2010;1(3):173–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi K, Kim J, Kim GW, Choi C. Oxidative stress-induced necrotic cell death via mitochondria-dependent burst of reactive oxygen species. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2009;6(4):213–222. doi: 10.2174/156720209789630375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chrissobolis S, Miller AA, Drummond GR, Kemp-Harper BK, Sobey CG. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in cerebrovascular disease. Front Biosci. 2011;16:1733–1745. doi: 10.2741/3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christians ES, Yan LJ, Benjamin IJ. Heat shock factor 1 and heat shock proteins: Critical partners in protection against acute cell injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1 Supp):S43–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasari VR, Kaur K, Velpula KK, Dinh DH, Tsung AJ, Mohanam S, Rao JS. Downregulation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) by cord blood stem cells inhibits angiogenesis in glioblastoma. Aging. 2010;2(11):791–803. doi: 10.18632/aging.100217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasari VR, Veeravalli KK, Saving KL, Gujrati M, Fassett D, Klopfenstein JD, Dinh DH, Rao JS. Neuroprotection by cord blood stem cells against glutamate-induced apoptosis is mediated by Akt pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32(3):486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson EH. Gene regulatory function in development. In: Davidson EH, editor. Genomic Regulatory Systems: Development and Evolution. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endo H, Nito C, Kamada H, Nishi T, Chan PH. Activation of the Akt/GSK3beta signaling pathway mediates survival of vulnerable hippocampal neurons after transient global cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(12):1479–1489. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fauconneau B, Petegnief V, Sanfeliu C, Piriou A, Planas AM. Induction of heat shock proteins (HSPs) by sodium arsenite in cultured astrocytes and reduction of hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death. J Neurochem. 2002;83(6):1338–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: Evolutionary and ecological physiology. Ann Rev Physiol. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaboli M, Kotsi PA, Gurrieri C, Cattoretti G, Ronchetti S, Cordon-Cardo C, Broxmeyer HE, Hromas R, Pandolfi PP. Mzf1 controls cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15(13):1625–1630. doi: 10.1101/gad.902301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Bonilla L, Benakis C, Moore J, Iadecola C, Anrather J. Immune mechanisms in cerebral ischemic tolerance. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:44. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasegawa Y, Hamada J, Morioka M, Yano S, Kawano T, Kai Y, Fukunaga K, Ushio Y. Neuroprotective effect of postischemic administration of sodium orthovanadate in rats with transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(9):1040–1051. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085160.71791.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedtjarn M, Mallard C, Eklind S, Gustafson-Brywe K, Hagberg H. Global gene expression in the immature brain after hypoxia-ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(12):1317–1332. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000141558.40491.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henning RJ, Sawmiller D, Fleming D, Hunter L, Aufman J, Morgan MB. Human umbilical cord blood stem cells secrete growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines that protect vascular endothelial cells and cardiac myocytes from ischemia and injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(10s1):A110. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang C, Li J, Costa M, Zhang Z, Leonard SS, Catranova V, Vallyathan V, Ju G, Shi X. Hydrogen peroxide mediates activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) by nickel subsulfide. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8051–8057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: Role of inflammatory cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 2010;87(5):779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Justicia C, Martin A, Rojas S, Gironella M, Cervera A, Panes J, Chamorro A, Planas AM. Anti-VCAM-1 antibodies did not protect against ischemic damage either in rats or in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(3):421–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamphuis W, Dijk F, Bergen AA. Ischemic preconditioning alters the pattern of gene expression changes in response to full retinal ischemia. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1892–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10(3):381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawano T, Morioka M, Yano S, Hamada J, Ushio Y, Miyamoto E, Fukunaga K. Decreased akt activity is associated with activation of forkhead transcription factor after transient forebrain ischemia in gerbil hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(8):926–934. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelley KW, Arkins S, Minshall C, Liu Q, Dantzer R. Growth hormone, growth factors and hematopoiesis. Hormone Res. 1996;45(1–2):38–45. doi: 10.1159/000184757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YD, Sohn NW, Kang C, Soh Y. DNA array reveals altered gene expression in response to focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58(5):491–498. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knoops B, Goemaere J, Van der Eecken V, Declercq JP. Peroxiredoxin 5: Structure, mechanism, and function of the mammalian atypical 2-Cys peroxiredoxin. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(3):817–829. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kropotov A, Gogvadze V, Shupliakov O, Tomilin N, Serikov VB, Tomilin NV, Zhivotovsky B. Peroxiredoxin V is essential for protection against apoptosis in human lung carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(15):2806–2815. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunze A, Zierath D, Tanzi P, Cain K, Becker K. Peroxiredoxin 5 (PRX5) is correlated inversely to systemic markers of inflammation in acute stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(2):608–610. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lan R, Xiang J, Zhang Y, Wang GH, Bao J, Li WW, Zhang W, Xu LL, Cai DF. PI3K/Aktpathway contributes to neurovascular unit protection of Xiao-Xu-Ming decoction against focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:459467. doi: 10.1155/2013/459467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latchman DS. Transcriptional control–transcription factors. In: Owen E, editor. Gene Regulation: A eukaryotic perspective. 5. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group; 2005. pp. 243–305. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee HJ, Lee JK, Lee H, Carter JE, Chang JW, Oh W, Yang YS, Suh JG, Lee BH, Jin HK, Bae JS. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve neuropathology and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model through modulation of neuroinflammation. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(3):588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li F, Omori N, Jin G, Wang SJ, Sato K, Nagano I, Shoji M, Abe K. Cooperative expression of survival p-ERK and p-Akt signals in rat brain neurons after transient MCAO. Brain Res. 2003;962(1–2):21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03774-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y, Huang J, He X, Tang G, Tang YH, Liu Y, Lin X, Lu Y, Yang GY, Wang Y. Postacute stromal cell-derived factor-1α expression promotes neurovascular recovery in ischemic mice. Stroke. 2014;45(6):1822–1829. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liesz A, Zhou W, Mracsko E, Karcher S, Bauer H, Schwarting S, Sun L, Bruder D, Stegemann S, Cerwenka A, Sommer C, Dalpke AH, Veltkamp R. Inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking shields the brain against deleterious neuroinflammation after stroke. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 3):704–720. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim JY, Park SI, Oh JH, Kim SM, Jeong CH, Jun JA, Lee KS, Oh W, Lee JK, Jeun SS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor stimulates the neural differentiation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells and survival of differentiated cells through MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling pathways. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(10):2168–2178. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipton SA. NMDA receptor activity regulates transcription of antioxidant pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(4):381–382. doi: 10.1038/nn0408-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu XQ, Sheng R, Qin ZH. The neuroprotective mechanism of brain ischemic preconditioning. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30(8):1071–1080. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo X, Zhang X, Shao W, Yin Y, Zhou J. Crucial roles of MZF-1 in the transcriptional regulation of apomorphine-induced modulation of FGF-2 expression in astrocytic cultures. J Neurochem. 2009;108(4):952–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manolagas SC, Almeida M. Gone with the Wnts: b-catenin, T-cell factor, forkhead box O and oxidative stress in age-dependent diseases of bone, lipid and glucose metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(11):2605–2614. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maslov LN. Signaling mechanism of neuroprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning of brain. Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter. 2013;2013(3):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, Iadecola C. The science of stroke: Mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron. 2010;67(2):181–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newcomb JD, Ajmo CT, Jr, Sanberg CD, Sanberg PR, Pennypacker KR, Willing AE. Timing of cord blood treatment after experimental stroke determines therapeutic efficacy. Cell Transplant. 2006;15(3):213–223. doi: 10.3727/000000006783982043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newcomb JD, Sanberg PR, Klasko SK, Willing AE. Umbilical cord blood research: Current and future perspectives. Cell Transplant. 2007;16(2):151–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newman MB, Willing AE, Manresa JJ, Davis-Sanberg C, Sanberg PR. Stroke-induced migration of human umbilical cord blood cells: Time course and cytokines. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(5):576–586. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nikolic WV, Hou H, Town T, Zhu Y, Giunta B, Sanberg CD, Zeng J, Luo D, Ehrhart J, Mori T, Sanberg PR, Tan J. Peripherally administered human umbilical cord blood cells reduce parenchymal and vascular beta-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer mice. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17(3):423–439. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozerlat I. ALCAM as a prognostic marker for acute ischemic stroke. Nature Rev Neurol. 2011;7(9):474. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panes J, Granger DN. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions: Molecular mechanisms and implications in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(5):1066–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plaisant F, Clippe A, Vander Stricht D, Knoops B, Gressens P. Recombinant peroxiredoxin 5 protects against excitotoxic brain lesions in newborn mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34(7):862–872. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi J-Y, Xu M, Lu ZZ, Zhang Y-Y. 14-3-3 inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I-induced proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajdev S, Hara K, Kokubo Y, Mestril R, Dillmann W, Weinstein PR, Sharp FR. Mice overexpressing rat heat shock protein 70 are protected against cerebral infarction. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(6):782–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ripka S, Neese A, Riedel J, Bug E, Aigner A, Poulsom R, Fulda S, Neoptolemos J, Greenhalf W, Barth P, Gress TM, Michl P. Cux1: Target of Akt signalling and mediator of resistance to apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2010;59(8):1101–1110. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.189720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rivers-Auty J, Ashton JC. Neuroinflammation in ischemic brain injury as an adaptive process. Med Hypotheses. 2014;82(2):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rowe DD, Leonardo CC, Hall AA, Shahaduzzaman MD, Collier LA, Willing AE, Pennypacker KR. Cord blood administration induces oligodendrocyte survival through alterations in gene expression. Brain Res. 2010;1366:172–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rowe DD, Leonardo CC, Recio JA, Collier LA, Willing AE, Pennypacker KR. Human umbilical cord blood cells protect oligodendrocytes from brain ischemia through Akt signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):4177–4187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.296434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samson Y, Lapergue B, Hosseini H. Inflammation and ischaemic stroke: Current status and future perspectives. Rev Neurol. 2005;161(12 Pt 1):1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(05)85190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sango K, Yanagisawa H, Komuta Y, Si Y, Kawano H. Neuroprotective properties of ciliaryneurotrophic factor for cultured adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130(4):669–679. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0484-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shahaduzzaman M, Golden JE, Green S, Gronda AE, Adrien E, Ahmed A, Sanberg PR, Bickford PC, Gemma C, Willing AE. A single administration of human umbilical cord blood T cells produces long-lasting effects in the aging hippocampus. Age. 2013;35(6):2071–2087. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9496-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin homeostasis through local production of insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(1):73–79. doi: 10.1038/ni1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shohami E, Beit-Yannai E, Horowitz M, Kohen R. Oxidative stress in closed-head injury: Brain antioxidant capacity as an indicator of functional outcome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17(10):1007–1019. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smedbakken L, Jensen JK, Hallen J, Atar D, Januzzi JL, Halvorsen B, Aukrust P, Ueland T. Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule and prognosis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2453–2458. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su Y, Cui L, Piao C, Li B, Zhao LR. The effects of hematopoietic growth factors on neurite outgrowth. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun HN, Kim SU, Huang SM, Kim JM, Park YH, Kim SH, Yang HY, Chung KJ, Lee TH, Choi HS, Min JS, Park MK, Kim SK, Lee SR, Chang KT, Lee SH, Yu DY, Lee DS. Microglial peroxiredoxin V acts as an inducible anti-inflammatory antioxidant through cooperation with redox signaling cascades. J Neurochem. 2010;114(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swart GW. Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (CD166/ALCAM): Developmental and mechanistic aspects of cell clustering and cell migration. Eur J Cell Biol. 2002;81(6):313–321. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Topcuoglu MA, Demirkaya S. Low plasma antioxidant activity is associated with high lesion volume and neurological impairment in stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(9):2273. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2266-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Towfighi A, Saver JL. Stroke declines from third to fourth leading cause of death in the United States: Historical perspective and challenges ahead. Stroke. 2011;42(8):2351–2355. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.621904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsoyi K, Jang HJ, Nizamutdinova IT, Park K, Kim YM, Kim HJ, Seo HG, Lee JH, Chang KC. PTEN differentially regulates expressions of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 through PI3K/Akt/GSK-3beta/GATA-6 signaling pathways in TNF-alpha-activated human endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2010;213(1):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vendrame M, Cassady J, Newcomb J, Butler T, Pennypacker KR, Zigova T, Sanberg CD, Sanberg PR, Willing AE. Infusion of human umbilical cord blood cells in a rat model of stroke dose-dependently rescues behavioral deficits and reduces infarct volume. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2390–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141681.06735.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vendrame M, Gemma C, Pennypacker KR, Bickford PC, Davis Sanberg C, Sanberg PR, Willing AE. Cord blood rescues stroke-induced changes in splenocyte phenotype and function. Exp Neurol. 2006;199(1):191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vieira SM, Lemos HP, Grespan R, Napimoga MH, Dal-Secco D, Freitas A, Cunha TM, Verri WA, Jr, Souza-Junior DA, Jamur MC, Fernandes KS, Oliver C, Silva JS, Teixeira MM, Cunha FQ. A crucial role for TNF-alpha in mediating neutrophil influx induced by endogenously generated or exogenous chemokines, KC/CXCL1 and LIX/CXCL5. Brit J Pharmacol. 2009;158(3):779–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang C, Qin L, Manes TD, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Tellides G, Pober JS. Rapamycin antagonizes TNF induction of VCAM-1 on endothelial cells by inhibiting mTORC2. J Exp Med. 2014;211(3):395–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang F, Maeda N, Yasuhara T, Kameda M, Tsuru E, Yamashita T, Shen Y, Tsuda M, Date I, Sagara Y. The therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord blood transplantation for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and ischemic stroke. Acta Med Okayama. 2012;66(6):429–434. doi: 10.18926/AMO/48962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Q, Tang XN, Yenari MA. The inflammatory response in stroke. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184(1–2):53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Womble TA, Green S, Shahaduzzaman M, Grieco J, Sanberg PR, Pennypacker KR, Willing AE. Monocytes are essential for the neuroprotective effect of human cord blood cells following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rat. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2014;59:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu J, Li Q, Wang X, Yu S, Li L, Wu X, Chen Y, Zhao J, Zhao Y. Neuroprotection by curcumin in ischemic brain injury involves the Akt/Nrf2 pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yoon JK, Park BN, Shim WY, Shin JY, Lee G, Ahn YH. In vivo tracking of 111In-labeled bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in acute brain trauma model. Nucl Med Biol. 2010;37(3):381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoshimura A, Ito M, Kondo T, Shichita T. Peroxiredoxin triggers post-ischemic inflammation. Seikagaku. 2013;85(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zachary I. Neuroprotective role of vascular endothelial growth factor: Signalling mechanisms, biological function, and therapeutic potential. NeuroSignals. 2005;14(5):207–221. doi: 10.1159/000088637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang HY, Zhang X, Wang ZG, Shi HX, Wu FZ, Lin BB, Xu XL, Wang XJ, Fu XB, Li ZY, Shen CJ, Li XK, Xiao J. Exogenous basic fibroblast growth factor inhibits ER stress-induced apoptosis and improves recovery from spinal cord injury. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013;19(1):20–29. doi: 10.1111/cns.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang MJ, Sun JJ, Qian L, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Cao W, Li W, Xu Y. Human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells enhance the expression of neurotrophic factors and protect ataxic mice. Brain Res. 2011;1402:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zheng L, Ishii Y, Tokunaga A, Hamashima T, Shen J, Zhao QL, Ishizawa S, Fujimori T, Nabeshima Y, Mori H, Kondo T, Sasahara M. Neuroprotective effects of PDGF against oxidative stress and the signaling pathway involved. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(6):1273–1284. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu H, Santo A, Li Y. The antioxidant enzyme peroxiredoxin and its protective role in neurological disorders. Exp Biol Med. 2012;237(2):143–149. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhu YM, Wang CC, Chen L, Qian LB, Ma LL, Yu J, Zhu MH, Wen CY, Yu LN, Yan M. Both PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways participate in the protection by dexmedetomidine against transient focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Brain Res. 2013;1494:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]