Abstract

Background

Many women diagnosed with breast cancer receive both standard cancer treatment and care from providers trained in the emerging field of medicine called ‘integrative oncology’ (IO) in which science-based complementary and alternative medical1 therapies are prescribed by physicians. The effectiveness of IO services has not been fully studied, so is yet unknown.

Purpose

Determine if a matched case-controlled prospective outcomes study evaluating the efficacy and safety of breast cancer IO care is feasible.

Methods

Methodological proof of principle requires demonstration that 1) it is possible to find matched control breast cancer patients using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program’s western Washington Cancer Surveillance System (CSS), and 2) an IO clinic can recruit breast cancer patients into a matched controlled study.

Results

A pilot study was conducted in 2008 (N=14) to determine if matched controlled women could be identified in the western Washington SEER database. All 14 women who were approached agreed to participate. The cases were matched to the CSS along five variables - age and stage at diagnosis, race, marital and ER/PR status. Multiple matches were found for 12 of the 14 participants.

Conclusion

A prospective cohort study with a matched comparison group is a feasible and potentially rigorous study design with high patient acceptability. It may provide valuable data for the evaluation of the effectiveness of IO care on patient health, relapse rate, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). A federally funded matched-case controlled outcomes study is currently underway at Bastyr University and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Keywords: breast cancer research methods, integrative oncology, naturopathic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine

Introduction

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)1 among breast cancer patients is significant and growing.2, 3 It is estimated that between 50% and 80% of women in the United States with breast cancer supplement their conventional medical treatment regimen with some form of CAM therapy.1, 4–9 Treatment is influenced by the growth of integrative oncology (IO) clinics that are operating, especially in large metropolitan areas of the United States. In spite of the growing number of cancer centers offering IO care, there has not yet been an adequate controlled study of clinical, laboratory, or quality of life outcomes associated with IO care.10, 11

IO care can improve patient outcomes through several possible mechanisms. These include the potential of improving the effectiveness of conventional treatments, treating side effects, and improving compliance. CAM treatments may facilitate cancer rehabilitation in the post-treatment setting, prevent cancer relapse, improve survival, and provide palliative end-of-life care. There are a number of botanical substances with demonstrated potent anti-cancer activity in vitro and in vivo.12, 13 Consultation with IO providers is also likely to improve health behaviors through patient education on nutrition, exercise, and stress reduction techniques. IO providers also counsel patients to avoid inappropriate CAM use that might lead to drug-herb or drug-nutrient interactions, potentially leading to reduced efficacy of standard care. CAM therapy may also provide patients with an opportunity to participate in decision-making about their treatment, leading them to feel they have some control of their health. This may increase patients’ satisfaction with their care and improve their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). The placebo effect of CAM is likely high in the IO setting because of the emphasis placed on communication and development of a therapeutic alliance with each patient and their family to address all levels of health (body, mind and spirit). For all these reasons, it would be valuable to assess the effects of IO holistically, and to assess a variety of outcomes including patient HRQOL and not just disease status or survival.

Integrative oncology studies to date

Many IO therapies involve the use of disease and immune modifying botanicals and nutrients that have varying levels of in-vivo evidence for anti-cancer activity. The anti-cancer mechanism of action of CAM therapies used in IO includes modulation of immunologic and molecular mechanisms of cancer initiation, promotion and metastasis. The basis of IO research has to date been of two types: 1) systematic reviews of randomized and non-randomized clinical trials of single natural product CAM treatments, such as mistletoe14, 15 and Trametes versicolor mushroom16–19; and 2) whole-person, health services oriented retrospective and prospective studies of IO survival outcomes compared to various non-randomized controls.

Randomized and non-randomized clinical trials of single natural product CAM treatments

The NIH has funded trials in both T. versicolor and mistletoe in Germany (NCT01378702), Korea (NCT00516022), Israel (NCT01401075; NCT 00516022) and the USA (NCT00079794; NCT00283478) to evaluate the safety and immunological effects of T. versicolor and mistletoe in phase I and II trials since 2001.

Based on these data, many IO physicians prescribe both T. versicolor and mistletoe to their cancer patients and they are often included in core protocols in IO clinics in the United States. Other specific targeted IO therapies such as curcumin, silymarin, resveratrol, garlic, omega-3 fatty acids, co-enzyme Q10, artemisinin, green tea and others, while in common use in IO clinics, are just now being evaluated in clinical trials as single agents. These products are available OTC and used by breast cancer patients and, at some IO clinics, prescribed as targeted therapies. As patients and clinicians await the results of these trials, studies using other methodologies, as they are commonly used in practice, would be helpful.

Use of historic data as controls in retrospective studies

Retrospective studies on survival outcomes in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving IO care have provided promising data regarding the possible survival benefit of IO care. Block et al were among the first to compare results in breast cancer patients treated at IO clinics with historical data published in breast cancer clinical trials. 20 Median survival in the IO-treated stage IV patients was 38 months and five-year survival was 27%, and this compared favorably to historic clinical trial results in stage IV breast cancer patients published in the 1990’s. Median survival reported in stage IV breast cancer ranged from 12 to 24 months and five-year survival was 17% among comparison patient data. These results may indicate a clinically significant treatment effect of IO care. However, the possibility of differences between the IO cases and the comparison women make the interpretation of the results uncertain. CAM-seeking cancer patients tend to be white, educated and employed, though this is also often true of clinical trial participants. Any differences in these demographics between the two groups might explain the difference in survival.

Use of ‘single visit’ controls to evaluate IO outcomes in lung cancer patients

McCulloch et al 21,22,23 have shown improved survival curves for stage I–IV lung and colon cancer patients receiving IO care at Pine Street Clinic located in the San Francisco Bay area. In 2006, this group presented retrospective outcomes data of survival in 239 non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) patients following treatment with an adjunctive natural medicine protocol that included science-based herbal and nutraceutical treatments similar to those utilized by other naturopathic and Chinese medicine IO physicians.21 The control group consisted of NSCLC patients who presented at the IO clinic but did not proceed with treatment. Treated patients showed an overall 44% reduced risk of death over 10 years compared to untreated controls, even when baseline treatment and health status adjustments were made. IO combined with conventional therapy, compared with conventional therapy alone, reduced the risk of death in stage I by 95%, stage II by 64%, stage III by 29%, and stage IV by 75%. Long-term IO care combined with conventional therapy improved survival, compared with conventional therapy alone. These data add indirect support for the hypothesis that adjunctive science-based natural medicine may have a positive survival benefit in lung cancer. McCulloch’s work is important because it demonstrates a significant clinical difference between lung patients who were exposed to IO care versus those that were motivated to make an appointment at the IO clinic but did not continue care after the first appointment. Results from McCulloch et al’s well-designed retrospective studies of IO with conventional therapy suggest that prospective studies of IO care combined with conventional treatment are warranted.

Methodological and ethical challenges associated with RCTs of IO oncology

Designing a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of IO care’s safety and efficacy, and not just a single agent treatment, faces several methodological challenges. First, federally-funded trials of IO care would require FDA approval to conduct research (INDs) for each element of IO care that involves a therapeutic substance (T. versicolor mushroom extract, mistletoe, curcumin, green tea, resveratrol, artemisinin, silymarin and melatonin to mention just a few commonly used IO treatments). Second, an IO RCT would require the development of a single standardized treatment algorithm that could be used as a strict protocol. Most IO clinics do not have strict standards of care or protocol guidelines of the sort needed for a definitive RCT, instead allowing providers to customize care to each individual patient. Third, once such a protocol is developed an estimated effect size for the protocol as a whole will be needed. If IO treatments are synergistic and their combination is more than the sum of their individual effects, this effect size could not be computed based on the effects found in single treatment studies. Estimates for conventional medicine RCTs examining behavioral and nutritional interventions commonly come from epidemiological research studies often conducted using non-randomized study designs and matched comparison groups.

There is also a potentially significant problem for an IO care RCT in patient recruitment. Patients already seeking IO care would be unlikely to enroll in a study with possible randomization to a non-treatment group. Similarly, those not already seeking IO care may be reluctant to sign up for randomization to IO activities they might find burdensome and that are not demonstrated to improve health.

Building strong evidence for efficacy of IO care may likely require RCTs. However, until we know more about the likely effects of IO care, we cannot proceed with RCTs. Therefore, it is appropriate to use other designs to create evidence to support an RCT proposal. For now, prospective outcomes studies using matched comparison women to assess the effects of IO care holistically via a health services approach may be most appropriate. The ethics of using clinical data collected from patients receiving reimbursed healthcare to evaluate those health services has been evaluated favorably. 24

Use of matched controlled studies to measure effect of CAM treatments in cancer patients

Matched controlled studies of CAM in breast cancer patients are rare. One, however, has been done. Lesperance et al., 2002 25 analyzed survival and recurrence outcomes in 90 women with unilateral non-metastatic breast cancer diagnosed between 1989 and 1998. All subjects were patients registered in the British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver Island Centre. Cases were women who were prescribed mega-doses of vitamins and minerals for at least two months by a single IO physician in addition to standard therapies. Control women were matched based on data available in hospital records including age, year of diagnosis, stage, TNM status, tumor grade, ER/PR status and conventional oncology treatment history. Breast cancer-specific survival and disease-free survival times were not improved for the vitamin/mineral treated group over those for the controls. These data support the use of a matched controlled design to evaluate IO effectiveness in breast cancer but are of limited value in evaluating these current IO practices for two reasons: 1) they did not control for CAM use in the control breast cancer patients, and 2) current day IO physicians rarely prescribe oral high dose vitamins and minerals except to correct deficiencies or for targeted short-term treatment.

While matching designs have added value and validity over historic literature controls, only clinics associated with major hospitals offering conventional treatment could use the methods used by Lesperance et al, 2002 25 to examine the outcomes of their care. Even then the size of sample a clinic associated with a single hospital can collect and examine is limited. We also know that CAM use and cancer outcomes are predicted by additional variables that the Lesperance study did not use for matching and which are commonly not available in routine hospital records. CAM use among breast cancer patients has been associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety, and these are associated with poorer outcomes in cancer patients. Ideally, education and ethnicity, which predict both CAM use and cancer outcomes, need to be included as matching variables in future matched controlled outcomes studies. A well-designed IO prospective outcomes study would also ideally include baseline measures of depression, anxiety and HRQOL in order to be able to control post-hoc for baseline status differences between IO cases and their matched controls.

A prospective matched controlled research design may provide adequate methodology to determine the safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of physician provided IO care. Such designs do not restrict patient choice and do not require a FDA IND for each element of the protocol. The difficulty of such studies for most clinics is in identifying appropriate comparison patients and collecting appropriate data on these comparison women. Using cancer registries to identify comparison patients who do not use IO could solve these problems. Such a study can be designed to include freestanding community IO clinics individually or networks of such clinics broadening the patient population studied and allowing for faster recruitment and enrollment which could allow for more timely evaluation.

We feel the IO field is now ready for well-designed matched controlled prospective epidemiological longitudinal studies of this type. But to whom exactly should IO clinic patients be compared? Clearly a matched comparison group should match the IO clinic cohort under study on as many disease status variables possible. This is the advantage of working with a cancer registry. Matching variables that are collected by a SEER cancer registry at patients’ diagnosis that could be included in IO matched controlled studies are shown in Table 1. Thus, patients in IO clinics in a cancer registry’s area of coverage could be identified and comparison patients with similar demographic characteristics and who were diagnosed with similar disease states could be identified.

Table 1.

SEER Cancer Surveillance System Variable List

| Patient personal identification data |

| Name |

| DOB |

| Zip code at time of diagnosis |

| SSN |

|

|

| Patient demographic identification |

| Race/ ethnicity |

| Marital status |

|

|

| Disease markers at FOC |

| Diagnosis date |

| TNM classification |

| Histopathology |

| Tumor markers (ER/PR, Her-2/neu) |

|

|

| Descriptive data |

| Conventional therapeutic regimen |

| Treatment timeline |

In order to examine the possibility that a cancer registry could provide the needed data to allow for the identification of a group of breast cancer patients suitable for study as comparison patients for a future study, we worked with the local site for the National Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute (SEER) (http://seer.cancer.gov) called the Washington State Cancer Surveillance System (CSS) (http://fhcrc.org/sharedresources.fhcrc.org/services/cancer-surveillance-system-css). The CSS is housed at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. Like many cancer registries it routinely provides data for epidemiological research studies.

This cancer registry has been found to reliably identify 99.8% of women in its 13 county recruitment area assuring access to a comprehensive listing of cancer patients and the possibility of identification of a representative sample of similar patients in a comparison group formed via the registry. Demonstration of feasibility requires that: 1) an IO clinic can recruit breast cancer patients into a matched controlled outcomes study; and 2) that it is possible to find matched control breast cancer patients using a cancer registry.

The Bastyr Integrative Oncology Research Center (BIORC) is an out-patient research center located on the Bastyr University campus in Kenmore, WA. Established in 2009, BIORC offers state-of-the-science CAM therapies to cancer patients, which are provided by CAM physicians, i.e., naturopathic physicians (NDs) who are board certified in naturopathic oncology and doctors of acupuncture and Oriental medicine (DAOM) who have specialty training in Chinese medicine oncology. IO medical providers are supported by a shared nursing staff and providers share patients’ medical charts. Complex cases are discussed among TCM and ND providers in a shared open office space. Progress notes are sent directly to each patient’s medical oncologist and primary care physician. Often treatment decisions in complex stage IV cancer cases will be made jointly by written, phone or email communications between IO and medical oncology providers.

At their first BIORC appointment patients are invited to participate in a prospective outcomes study and, if agreeable, are then consented to participate. After signing an informed consent form and a medical records release form, they are then asked to complete a 30 minute questionnaire which is offered again at six months, and then annually for five years or more. Baseline demographic data are acquired at the first appointment, and used to identify each cancer patient in the CSS registry and to find potential matched comparison patients. The questionnaire also includes validated instruments to assess health-related quality of life (HRQOL); the Medical Outcomes Survey (SF-36), worry about cancer scale (IES), Perceived Stress Scale, Meaning in Cancer Experience survey and Cancer Treatment Decision Making. Each patient is asked about their current marital and financial status and CAM use prior to their use of the clinic. Follow-up questionnaires assess general CAM use and adherence to IO prescriptions and treatments recommended at the clinic as these are potential predictors of cancer outcomes.

Matching IO cases to the cancer registry

Prior to opening BIORC we needed to insure that the CSS contained adequate numbers of potential matches for IO breast cancer patients. In 2008, we designed a pilot study to demonstrate the acceptability to patients of such procedures and the feasibility of using the registry to identify women matched for demographic and disease characteristics at the time of their diagnosis; and thus allowing us to determine whether there are a sufficient number of cases with similar prognostic characteristics in the registry to allow for matching. This pilot study was approved by both the Internal Review Boards’ of Bastyr University (BU) and of the FHCRC). We asked the CSS to find matched control women for fourteen (n=14) women with breast cancer cases receiving IO treatment under the care of the first author. These fourteen women, matched in terms of age, stage at diagnosis, estrogen and progesterone receptor status, ethnicity and marital status, agreed to participate. They signed a consent form, completed a questionnaire and their names were provided to the cancer registry.

RESULTS

When the CSS registry was queried about the existence of other breast cancer cases matching the demographic and disease characteristics of the IO breast cancer case women, the results shown in Table 2 below were obtained.

Table 2.

Results of matching pilot study demonstrating the ability to match BIORC breast cancer patients who receive integrative oncology care using the SEER CSS Registry.

| ID | Year of Diagnosis | Race | Ethnicity | Marital Status | Stage | ER | PR | # of Matches within 2 years of age | # of Matches within 5 years of age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-014 | 2000 | White | 0 | 2 | Localized | + | + | 81 | 155 |

| B-012 | 2003 | White | 0 | 2 | regional | + | + | 77 | 137 |

| B-002 | 2006 | White | 0 | 2 | Localized | + | + | 16 | 41 |

| B-001 | 2007 | White | 0 | 2 | metastatic | + | + | 4 | 7 |

| B-021 | 2007 | n/a | n/a | n/a | Localized | − | − | 3 | 6 |

| B-019 | 2007 | White | 0 | 1 | Localized | + | − | 1 | 2 |

| B-020 | 2007 | White | 0 | 1 | Localized | − | − | 6 | 6 |

| B-010 | 2007 | White | 0 | 1 | Localized | + | + | 10 | 34 |

| B-011 | 2008 | White | 0 | 1 | Localized | + | + | 20 | 33 |

| B-003 | 2008 | White | Hispanic | n/a | regional | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| B-015 | 2009 | n/a* | n/a* | n/a* | n/a | + | + | 12 | 29 |

| B-016 | 2009 | n/a* | n/a* | n/a* | metastatic | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| B-017 | 2009 | n/a* | n/a* | n/a* | in-situ | + | + | 5 | 15 |

| B-018 | 2009 | n/a* | n/a* | n/a* | n/a | + | + | 8 | 13 |

0 = no ethnicity

1 = single

2 = married

Data on demographics in registry incomplete at time of match for women who had been diagnosed in 2009. It may take up to 6 months for Western Washington CSS to collect and enter data into the registry.

Using the criteria that the case and the control must each have been diagnosed within two years of each other, we found eligible matched controls for 12 of the 14 participants (87%) ranging from 1–81 matches each with an average of 20 matches/ IO patient. However, the CSS was unable to find matches for two of the study patients; one woman of Hispanic ethnicity (there is only a small Hispanic population in the greater Seattle metropolitan area) and one relatively rare breast cancer case of a pre-menopausal woman with newly diagnosed with stage IV lobular breast cancer. With two exceptions, our pilot matching protocol demonstrates that the CSS registry contains an adequate number of potential matched controls for most IO breast cancer cases. When the age at diagnosis criteria is relaxed from within 2 years to within 5 years, many more matches were obtained. (See Table 2.) These pilot data provided methodological proof of principle and evidence of feasibility to proceed with a matched controlled prospective outcomes study of IO care in breast cancer patients.

Discussion

Based on pilot data showing that identifying breast cancer patients who match IO patients on key demographic and disease characteristics is feasible, we proceeded to design and propose a prospective matched controlled outcomes study, which is now funded and underway. We hypothesized that a matched case-control prospective outcomes study of breast cancer integrative oncology was feasible and could provide valuable data regarding key questions regarding whether and how well IO and CAM treatments work. We selected breast cancer because it is among the most common cancers and one IO clinic providers see frequently. Also the widespread use of self-prescribed CAM and IO services by this group of patients 2 and the burgeoning body of scientific data which elucidate the mechanism of action of some commonly used modalities 1, 17, 26, 27 makes this group of particular interest scientifically.

Prospective Outcomes Monitoring Study design considerations

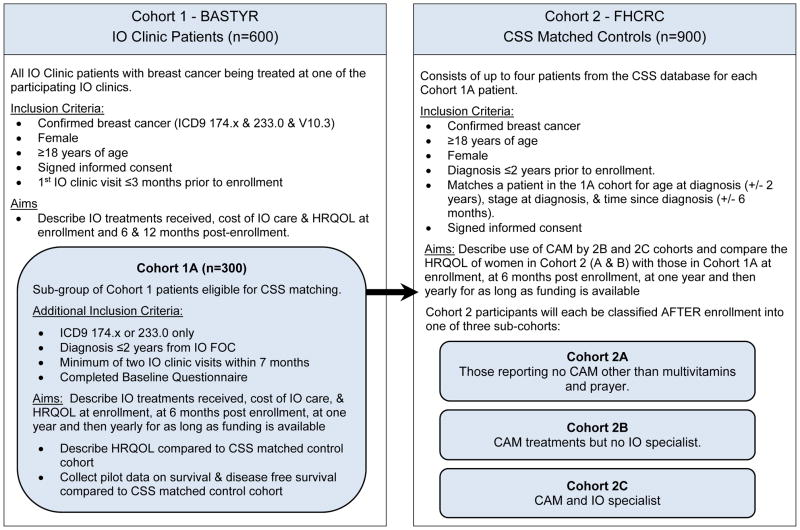

Most breast cancer patients who seek out IO also complete standard treatments including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and hormone treatments. Some of these patients do so before seeking IO care and others do not. They may also seek CAM treatments either on their own or seek care from CAM professional (chiropractors, massage therapists, etc.) who do not have specialty training or board certification in integrative oncology. Because self-prescribed CAM use and care from non-expert licensed care CAM professionals is widespread among breast cancer patients, we felt a matched controlled outcomes study should include an assessment of both CAM and conventional care received. Thus a matched controlled outcomes study requires separate examination of five cohorts nested within IO patients and CSS matched controls.

Cohorts

Cohort 1: IO cases (Breast cancer cases receiving integrated oncology treatment in addition to standard care (SC)

Cohort 1a: a subset of IO cases who have been diagnosed within 2 years of the first office visit (FOC) to an IO clinic Comparison groups:

Cohort 2a: SC alone (Standard care alone no reported CAM use)

Cohort 2b: CAM +SC (Breast cancer patients who use CAM treatments, most of which they would self-prescribe in addition to standard care.) This group includes breast cancer patients who receive care from licensed CAM providers who do not have advanced oncology training. Such a group could be examined separately depending on the availability of enough patients for each group.

Cohort 2c: CAM + non-research site IO. This group includes breast cancer patients who receive care from licensed IO providers who are not part of any of the participating IO clinical research sites. We expect this cohort to be small in number because we have recruited the most well-known IO clinics with the highest census. We will compare baseline and changes in HRQOL in breast cancer patients who self-prescribe CAM (Cohort 2B) matched with comparison women who do not use CAM (Cohort 2A). See Table 3 for definitions of the cohorts.

TABLE 3.

Cohort descriptions for a prospective matched controlled outcomes study of IO care.

For this study FHCRC and BU have recruited the participation of five additional western Washington State IO clinics (NCT01366248; http://clinicaltrials.gov) see Table 4 for the six Western Washington IO clinic recruitment sites.

Table 4.

Six western Washington IO clinic recruitment sites for Breast Cancer IO Prospective Matched Controlled Outcomes Study

| IO Clinic | Address | Study Clinician(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Bastyr Integrative Oncology Research Center | Kenmore, WA 98028 | Leanna J. Standish, ND, PhD, LAc, FABNO |

| Institute of Complementary Medicine | Seattle, WA 98122 | Chad Aschtgen, ND, FABNO |

| Red Cedar Wellness Center | Bellevue, WA 98004 | Janile Martin, ND, FABNO Laura A. James, ND, FABNO |

| Seattle Integrative Oncology at Providence Integrative Cancer Care | Lacey, WA 98503 | Chad Aschtgen, ND, FABNO |

| Seattle Cancer Treatment & Wellness Center | Renton, WA 98057 | Paul Reilly, ND, FABNO Mark Gignac, ND, FABNO Letitia Cain, ND, FABNO |

Care at each IO clinic includes evaluation and management by a naturopathic physician with board certification in naturopathic oncology (Fellows of the American Board of Naturopathic Oncology, http://www.oncanp.org/nat_onc.html). While specific treatments differ among the IO clinics, the approach and modalities are similar and include botanical and nutritional medicine (oral, parenteral), mind-body medicine, and exercise programs. Acupuncture is often recommended by NDs for symptom management and palliative care 28. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is provided by a co-licensed ND/L.Ac. or by referral to a DAOM (Doctor of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine) who specializes in oncology. (http://www.bastyr.edu/education/acupuncture/degree-curriculum/DAOM.asp). Most IO clinics include TCM evaluation and management that includes Chinese herbal formulas, moxibustion, qi gong and dietary recommendations. One aim of the IO outcomes study is to describe variations across IO clinics in type, dose and frequency of IO treatments prescribed. With time and sufficient number of enrolled patients, we will be able to associate IO treatments with specific outcomes.

The BU/FHCRC Breast Cancer Outcomes Study tracks each patient’s conventional oncologic treatment as well as IO therapies prescribed. Patient adherence and ability to tolerate both standard of care and IO treatments are tracked. Data on all conventional adjunctive treatments that are prescribed and completed are obtained from oncology medical records. Data on all IO care treatment recommendations are collected from the attending IO physician’s medical record. Adherence to IO treatment recommendations are assessed in the questionnaire each patient fills out at baseline, 6 months and then yearly.

Each IO clinic uses a standard set of recruitment and enrollment procedures and forwards data to BU and the FHCRC who coordinate work with the CSS registry. At baseline each participant patient completes informed consent procedures and signs a medical records release. IO cases fill out a 30 minute baseline questionnaire either at their first IO clinic visit or by mail shortly after. FHCRC mails questionnaires again at six months, then annually for five years or more. Each patient is asked about their current marital and financial status, as well as adherence to IO prescriptions and treatments recommended, as these are potential predictors of cancer outcomes.

Medical data are collected from each IO patient’s chart and includes the following variables: relapse status, stage, histology, tumor markers, ER, PR, and Her-2/neu recent scan reports, IO and conventional treatments including surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, monoclonal antibody therapy, and radiotherapy (and doses) received, co-morbidities, date of relapse and date of death. Laboratory data that are extracted include tumor marker values, 25-OH-vitamin D, and natural killer cell activity. The REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) clinical database is used for data entry and analysis. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. 29

Data on adverse effects of IO treatment will be collected using the Monitoring of Side Effects Scale (MOSES). These data are categorized for type and rated for severity using the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE VERSION 4.D). They will be used to assess safety of IO care. In order to evaluate cost-effectiveness of IO, we collect data on the cost of consultations and procedures (mostly reimbursed by third party payers) and IO pharmacy that is not covered by medical insurance.

Matched control subjects are eligible if they were diagnosed within 2 years of the IO case and invited to participate by FHCRC staff. Controls will be queried about their use of CAM, both self- and physician prescribed, so that each can be assigned to one of the following categories: 1) breast cancer cases receiving integrated oncology treatment in addition to standard care, 2) those that receive standard care alone, 3) breast cancer patients who self-prescribe CAM in addition to standard care, or 4) breast cancer patients who receive care from licensed CAM providers who are not part of the selected IO clinics. All follow-up questionnaires are distributed and collected by study staff working at FHCRC who will assure that all follow-up data is collected using identical procedures in both the IO case and both comparison groups.

Using a matched control comparison cohort as a study design, it may be possible to determine if IO care improves breast cancer survivor’s HRQOL at 6 and 12, 24, 36, 48, 60 months and forward in time after the initiation of IO care. The BU/FHCRC partnership has taken the necessary first steps to be able to compare outcomes including relapse-free survival and changes in HRQOL with that of women from the comparison cohort matched for prognosis at diagnosis who have not used IO care but have, and have not, used CAM treatments on their own. To assure that the clinical outcome measures of this IO study are commensurate with NCI guidelines we will use the definition of ‘invasive disease free survival’ derived from a panel of experts in breast cancer clinical trials representing medical oncology, biostatistics, and correlative science, as noted in Hudis et al, 2007. 30

A prospective matched case-comparison cohort will provide preliminary data where none are currently available. It may allow us to describe a standard protocol and provide an effect size estimate necessary before a RCT of IO care can be proposed. Collaboration with the western Washington State CSS registry allows for identification of an appropriate comparison group of women who have similar prognoses at diagnosis and on whom similar data on medical care use and outcomes can be collected.

Measuring IO Treatment Adherence

The 6 month and yearly questionnaire that is mailed to each study participant includes two questions to capture compliance with IO recommendations and prescriptions for IO substances, procedures, activities and referrals.

“Please provide information for each provider listed below. Check the box indicating the provider you have seen, provide the date of your last appointment.” The list contains “oncologist, primary care physician, naturopathic doctor, Chinese medicine provider, chiropractor, massage therapist, or other”.

“We are interested in your use of the following foods, herbs, and other substances. If you used these foods, herbs or other substances, please indicate with check marks those you used and answer the questions about that substance.” The list contains 70 CAM substances (herbs, nutriceuticals, etc.) and 33 CAM activities (acupuncture, yoga, biofeedback etc.).

Sample size considerations

We anticipate that enrollment of four women with breast cancer from the CSS registry per IO clinic-identified case receiving IO care will yield sufficient matched control women per IO case (1 case: up to 4 controls) for comparison purposes. This includes both matched women who do not use CAM treatments and matched women who use self-prescribed CAM treatments independent of a licensed CAM provider or MD with specialty training in IO. Such a cohort will allow us to provide a comprehensive description of CAM use and CAM users in a community setting and prospective examination of the influence of IO care and, perhaps, self-prescribed CAM treatment on the HRQOL of users. Collection of outcomes data on the patient cohorts will include survival, disease-free survival and a comprehensive multi-dimensional assessment of HRQOL. Short-term endpoints are changes in HR-QOL. We calculate that a sample size of 300 IO cases and 1200 matched controls would provide adequate power for a study that compared clinical outcomes of IO plus standard care compared to standard care alone. Long-term outcomes of disease free survival and relapse rates will require at least five years of data.

Our results thus far demonstrate that matching a cohort of IO patients to a matched group of women with breast cancer using a cancer registry is possible and provides a methodology by which the effectiveness of IO as routinely practiced in a community could be studied.

Conclusion

Based on the arguments and pilot data presented in this paper, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine is supporting a prospective matched-controlled breast cancer IO outcomes study (2010–2015). This study, currently underway at Bastyr University and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, is collecting quality of life and clinical outcome data from breast cancer patients receiving IO care in western Washington State. As of September 2011 the Bastyr/FHCRC study has enrolled 175 integrative oncology breast cancer cases and 78 matched controls.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Cleavage Creek Winery and NCCAM grant R01 AT5873.

Supported by NIH-NCCAM grants U19 AT1998, R01 AT5873, U19 AT6028 and Cleavage Creeks Cellars

Footnotes

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Leanna J. Standish, Bastyr University.

Erin Sweet, Bastyr University.

Eleonora Naydis, Bastyr University.

M. Robyn Andersen, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

References

- 1.Danhauer SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: findings from a randomized pilot study. Psycho-Oncology. 2009 Apr;18(4):360–368. doi: 10.1002/pon.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenlee H, Kwan ML, Ergas IJ, et al. Complementary and alternative therapy use before and after breast cancer diagnosis: the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Jan 31; doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahleh Z, Tabbara IA. Complementary and alternative medicine in breast cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2003 Sep;1(3):267–273. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navo MA, Phan J, Vaughan C, et al. An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynecologic or breast malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Feb 15;22(4):671–677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiGianni LM, Garber JE, Winer EP. Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Sep 15;20(18 Suppl):34S–38S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray RE, Fitch M, Goel V, Franssen E, Labrecque M. Utilization of complementary/alternative services by women with breast cancer. J Health Soc Policy. 2003;16(4):75–84. doi: 10.1300/J045v16n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson JW, Donatelle RJ. Complementary and alternative medicine use by women after completion of allopathic treatment for breast cancer. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004 Jan-Feb;10(1):52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashikaga T, Bosompra K, O’Brien P, Nelson L. Use of complimentary and alternative medicine by breast cancer patients: prevalence, patterns and communication with physicians. Support Care Cancer. 2002 Oct;10(7):542–548. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen J, Andersen R, Albert PS, et al. Use of complementary/alternative therapies by women with advanced-stage breast cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002 Aug 13;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagliaferri M, Cohen I, Tripathy D. Complementary and alternative medicine in early-stage breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2001 Feb;28(1):121–134. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber B, Scholz C, Reimer T, Briese V, Janni W. Complementary and alternative therapeutic approaches in patients with early breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006 Feb;95(3):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, et al. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm Res. 2008 Sep;25(9):2097–2116. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Standish LJAL, Ready A, Sivam G, Torkelson C, Wenner C. Textbook of Integrated Oncology: Botanical Oncology. Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kienle GS, Glockmann A, Schink M, Kiene H. Viscum album L. extracts in breast and gynaecological cancers: a systematic review of clinical and preclinical research. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:79. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostermann T, Raak C, Bussing A. Survival of cancer patients treated with mistletoe extract (Iscador): a systematic literature review. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:451. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh TC, Wu JM. Cell growth and gene modulatory activities of Yunzhi (Windsor Wunxi) from mushroom Trametes versicolor in androgen-dependent and androgen-insensitive human prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2001 Jan;18(1):81–88. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Standish LJ, Wenner CA, Sweet ES, et al. Trametes versicolor mushroom immune therapy in breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2008 Summer;6(3):122–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasser SP, Weis AL. Therapeutic effects of substances occurring in higher Basidiomycetes mushrooms: a modern perspective. Crit Rev Immunol. 1999;19(1):65–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zjawiony JK. Biologically active compounds from Aphyllophorales (polypore) fungi. J Nat Prod. 2004 Feb;67(2):300–310. doi: 10.1021/np030372w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block KI, Gyllenhaal C, Tripathy D, et al. Survival impact of integrative cancer care in advanced metastatic breast cancer. Breast J. 2009 Jul-Aug;15(4):357–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCulloch MBM, Gao J, Colford J. Survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients following treatment with an adjunctive Chinese herbal/vitamin protocol. Paper presented at: National Cancer Institute Conference on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Cancer Research; 2006; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCulloch M, Broffman M, van der Laan M, et al. Lung cancer survival with herbal medicine and vitamins in a whole-systems approach: ten-year follow-up data analyzed with marginal structural models and propensity score methods. Integr Cancer Ther. 2011;10(3):260–279. doi: 10.1177/1534735411406439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCulloch M, Broffman M, van der Laan M, et al. Colon Cancer Survival With Herbal Medicine and Vitamins Combined With Standard Therapy in a Whole-Systems Approach. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2011 Sep 1;10(3):240–259. doi: 10.1177/1534735411406539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans S, Block JB. Ethical issues regarding fee-for-service funded research within a complementary medicine context. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2001;7(6):697–702. doi: 10.1089/10755530152755252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesperance ML, Olivotto IA, Forde N, et al. Mega-dose vitamins and minerals in the treatment of non-metastatic breast cancer: an historical cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002 Nov;76(2):137–143. doi: 10.1023/a:1020552501345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider C, Segre T. Green tea: potential health benefits. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Apr 1;79(7):591–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirpara KV, Aggarwal P, Mukherjee AJ, Joshi N, Burman AC. Quercetin and its derivatives: synthesis, pharmacological uses with special emphasis on anti-tumor properties and prodrug with enhanced bio-availability. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009 Feb;9(2):138–161. doi: 10.2174/187152009787313855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Standish LJ, Kozak L, Congdon S. Acupuncture is underutilized in hospice and palliative medicine. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008 Aug-Sep;25(4):298–308. doi: 10.1177/1049909108315916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, et al. Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: the STEEP system. J Clin Oncol. 2007 May 20;25(15):2127–2132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]