Abstract

Background

Pulmonary sequestration (PS), a rare congenital anatomic anomaly of the lung, is usually treated through resection by a conventional thoracotomy procedure. The efficacy and safety of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) in PS treatment has seldom been evaluated. To address this research gap, we assessed the efficacy and safety of VATS in the treatment of PS in a large Chinese cohort.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 58 patients with PS who had undergone surgical resection in our department between January 2003 and April 2014. Of these patients, 42 (72.4%) underwent thoracotomy, and 16 (27.6%) underwent attempted VATS resection. Clinical and demographic data, including patients’ age, sex, complaints, sequestration characteristics, approach and procedures, operative time, resection range, blood loss, drainage volume, chest tube duration, hospital stay, and complications were collected, in addition to short-term follow-up data.

Results

Of the 58 participating patients, 55 accepted anatomic lobectomy, 2 accepted wedge resection, and 1 accepted left lower lobectomy combined with lingular segmentectomy. All lesions were located in the lower lobe, with 1–4 aberrant arteries, except one right upper lobe sequestration. Three cases (18.8%) in the VATS group were converted to thoracotomy because of dense adhesion (n=1), hilar fusion (n=1), or bleeding (n=1). No significant differences in operative time, postoperative hospital stay, or perioperative complications were observed between the VATS and thoracotomy groups, although the VATS patients had less blood loss (P=0.032), a greater drainage volume (P=0.001), and a longer chest tube duration (P=0.001) than their thoracotomy counterparts.

Conclusions

VATS is a viable alternative procedure for PS in some patients. Simple sequestration without a thoracic cavity or hilum adhesion is a good indication for VATS resection, particularly for VATS anatomic lobectomy. Thoracic cavity and hilum adhesion remain a challenge for VATS.

Keywords: Pulmonary sequestration (PS), anatomic lobectomy, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS)

Introduction

Pulmonary sequestration (PS) is a rare congenital anatomic anomaly, although it is being reported with increasing frequency. PS is characterized as nonfunctional lung tissue without a normal tracheobronchial tree that is fed by an aberrant systemic artery (1). Many researchers have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of thoracotomy in treating PS (2,3). However, with the development of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), increasing numbers of pulmonary diseases are suited to being treated with VATS because of its optimal results. Thoracoscopic surgery may provide an alternative treatment option for PS (4,5), but its safety and efficacy have rarely been evaluated. In the study reported herein, we retrospectively reviewed the clinical characteristics of patients with PS who had undergone a total thoracoscopic resection and compared them with those of patients who had undergone thoracotomy in a large Chinese cohort.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed consecutive PS patients who had undergone surgical resection in the Thoracic Department of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, between January 2003 and April 2014. Patients were selected for VATS or thoracotomy according to the following criteria: peripheral lesion without a thoracic cavity and hilum adhesion evaluated by computed tomography (CT), adequate cardiopulmonary reserve, and no history of ipsilateral thoracic operation. The extent of pulmonary resection was mainly determined by the diameter and location of the lesion and the degree of lung function. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

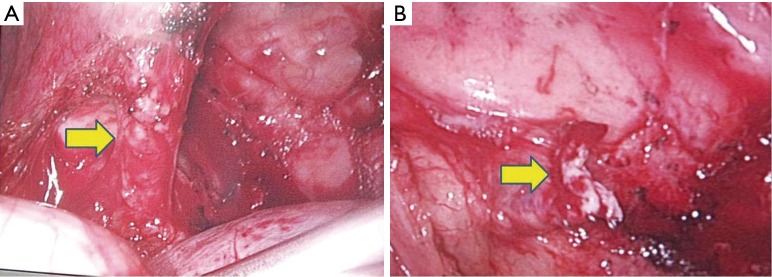

Patients were positioned in a lateral decubitus position, and double-lumen intubations were performed for single lung ventilation. Open thoracotomy was performed through conventional posterolateral latissimus dorsi-preserved thoracotomy. VATS was performed through 3 port incisions: an observation port (1 cm) at the seventh intercostal space in the mid-axillary line; working port (3–5 cm) in the fourth intercostal space in the anterior axillary line without rib spreading; and auxiliary port (1–2 cm) in the eighth intercostal space between the posterior axillary line and linea scapularis. Our experience suggested that it was unnecessary to change the location of the port with respect to the site of the lesion. The inferior pulmonary ligament was separated to mobilize the ectopic vessels. Drawing on our experience, we separated the ectopic vessels closest to the lung tissue to avoid uncontrolled bleeding, and then ligated the ectopic vessels before dissecting them with a lineal stapler to avoid laceration and rupture of the stamp. The lineal stapler is placed through working port with the tip between the ectopic vessels and lung tissue. The lung tissue is pulled into the stapler, while the tip is held in place. Then, the dissection between vessels and lung tissue is continued (Figure 1). Subsequently, we separated the normal structures and performed a routine dissection. All patients were managed postoperatively and discharged with few complications. At a three-month follow-up, we observed that all ectopic vessels had been resolved.

Figure 1.

The produce of dissection aberrant artery. (A) The aberrant artery (arrow) is separated in the operation; (B) the aberrant artery (arrow) is cut with a stapling device.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The quantitative variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and presented as mean ± standard deviations using an independent-samples t-test. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Between January 2003 and April 2014, 76 patients were diagnosed with PS in our department, of whom 58 underwent pulmonary resection. VATS was attempted on 16 of these patients, and 42 were treated via posterolateral thoracotomy. The clinical characteristics of the two patient groups are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of VATS and thoracotomy groups.

| Characteristics | VATS group (n=16) | Thoracotomy group (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male:female) | 11:5 | 23:19 | 0.334 |

| Age (years) | 34.2±14.0 | 38.7±13.5 | 0.261 |

| Preoperative symptoms | 12 | 30 | 0.786 |

| Preoperative misdiagnosis | 4 | 18 | 0.210 |

| Location of sequestration (RL:LL) | 3:13 | 8:34 | 0.979 |

| Type of sequestration (ELS:ILS) | 0:16 | 4:38 | 0.484 |

| Origin of aberrant artery (TA:AA:other) | 14:2:0 | 36:4:2 | 0.649 |

| Number of aberrant artery (1:2:3) | 14:1:1 | 38:3:1 | 0.768 |

VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery; RL, right lung; LL, left lung; ELS, extralobar sequestration; ILS, intralobar pulmonary sequestration; TA, thoracic aorta; AA, abdominal aorta.

No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of their clinical characteristics. Forty-two patients (72.4%) exhibited preoperative symptoms: recurrent pneumonia (cough, expectoration and fever) in 27 cases; hemoptysis or bloody sputum in 10 cases; chest pain in 4 cases; and chest distress in 1 case (Table 2). No symptoms were present in 16 cases. Thirty-six patients (62.1%) were diagnosed preoperatively by computed tomographic angiography (CTA) with an obviously aberrant artery, but others were misdiagnosed with lung cancer, bronchiectasis, or other infectious lesions. In the majority of patients, the PS was located in the lower lobe (98.3%), with the left lower lobectomy (LLL) a more frequent location than the right lower lobe (RLL) (LLL:RLL =46:11). In this type of PS, intralobar pulmonary sequestration (ILS) is more common than extralobar pulmonary sequestration (ELS) (ILS:ELS =54:4). All ectopic vessels were resolved after lung resection. Patients with infections were given antibiotic therapy preoperatively, and those without were given antibiotic prophylaxis.

Table 2. Preoperative symptoms of VATS and thoracotomy groups.

| Main symptoms | VATS group (n=12) | Thoracotomy group (n=30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | 2 | 2 | 0.319 |

| Expectoration | 6 | 6 | 0.052 |

| Fever | 2 | 9 | 0.375 |

| Hemoptysis | 1 | 7 | 0.263 |

| Bloody sputum | 0 | 2 | 0.909 |

| Chest pain | 1 | 3 | 0.868 |

| Chest distress | 0 | 1 | 0.631 |

VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Forty-four patients (75.9%) exhibited pleural adhesion intraoperatively, of which only 10 cases were dense adhesion. Three patients in the VATS group were converted to thoracotomy because of dense adhesion (n=1), hilar fusion (n=1), or bleeding (n=1). With the exception of one case in the thoracotomy group, in which more than one aberrant artery injury occurred and was treated properly with a blood loss of approximately 500 mL, no patients received intraoperative or postoperative transfusions. An aberrant artery from the thoracic aorta was confirmed in 50 patients (86.3%), an abdominal aorta in 6 patients (10.3%), pulmonary artery in 1 patient (1.7%), and subclavian artery in 1 patient (1.7%). Fifty-two patients (89.7%) were confirmed to have one aberrant artery, 4 (6.9%) to have two, and 2 (3.4%) to have three. The venous return of all patients was noted to be through the pulmonary vein.

All 58 patients underwent pulmonary resection: 55 accepted anatomic lobectomy, 2 accepted wedge resection, and 1 accepted left lower lobectomy combined with lingular segmentectomy. No significant differences were found between the two patient groups in terms of operative time, postoperative hospital stay, or perioperative complications, although the VATS patients experienced less blood loss (P=0.032) and had a greater drainage volume (P=0.001) and longer chest tube duration (P=0.001) than the thoracotomy patients (Table 3).

Table 3. Perioperative clinical data of VATS and thoracotomy groups.

| Clinical data | VATS group (n=16) | Thoracotomy group (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 122±40 | 129±36 | 0.500 |

| Resection range (LR:WR) | 15:1 | 40:2 | 0.628 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 116±90 | 210±162 | 0.032 |

| Drainage volume (mL) | 900±463* | 555±279 | 0.001 |

| Chest tube duration (day) | 5.88±1.36 | 3.98±1.66 | 0.001 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 7.44±2.03 | 7.14±1.92 | 0.609 |

| Postoperative complications (yes:no) | 5:11 | 6:36 | 0.272 |

*, except one patient with lymphorrhagia (n=15). VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery; LR, lobectomy resection; WR, wedge resection.

No perioperative deaths occurred in either group, although 11 patients experienced postoperative complications (Table 4): 3 cases of pulmonary infection (1 case of secondary aspergillus infection); 3 cases of intractable air leakage (cured by pleurodesis); 2 cases of delayed bleeding (cured by secondary hemostasis); 1 case of lymphorrhagia (cured by thoracic duct ligation); 1 case of cardiac arrhythmia (cured by medical therapy); and 1 case of pleural effusion (cured by thoracentesis). No significant difference in perioperative complications was observed between the two groups (P=0.272).

Table 4. Postoperative complications of VATS and thoracotomy groups.

| Perioperative complications | VATS group (n=16) | Thoracotomy group (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary infection | 1 | 2 | |

| Intractable air leakage | 1 | 2 | |

| Delayed bleeding | 0 | 2 | |

| Lymphorrhagia | 1 | 0 | |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 1 | 0 | |

| Pleural effusion | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 0.272 |

VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Of the 58 participating patients, 8 were lost to follow-up. The follow-up period for the other 50 patients ranged from 2 to 66 months, with a median of 36 months. No deaths or recurrences occurred during the follow-up period.

Discussion

PS is a congenital lung malformation that is usually detected as non-functional pulmonary tissue vascularized by an aberrant artery but without a normal bronchopulmonary tree (6). Since its first description by Huber in 1877 (7), PS has accounted for 0.15–6.4% of all reported congenital lung anomalies (8). It is usually classified as either extralobar or intralobar.

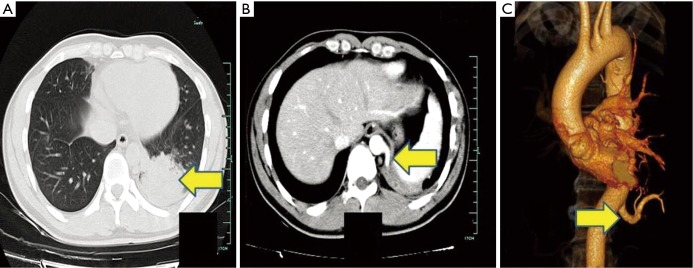

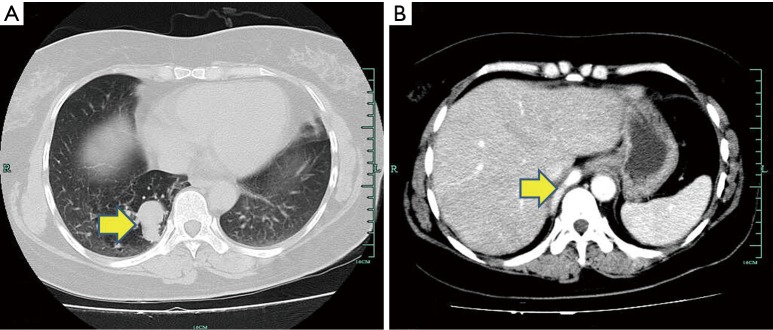

Because PS constitutes a benign lesion accompanied by such complications as cough, sputum, fever, and hemoptysis, but is not specific, it is difficult to diagnose preoperatively. The condition is more common in the lower lobes (2). Hence, physicians should be alert to it when a solid lesion is detected in the lower lobe, particularly when the lesion is close to the mediastinum. Tomographic angiography, three-dimensional CTA in particular, can show the aberrant blood vessels and thus assist in diagnosis (9,10) (Figures 2,3). However, PS has no specific clinical symptoms, and CTA is not routinely performed for all patients. In our study, misdiagnosis occurred in 22 cases (37.9%) before the aberrant vessels were detected intraoperatively. One patient in the VATS group suffered a massive hemorrhage and was converted to the thoracotomy group.

Figure 2.

The left aberrant blood vessel is detected by tomographic angiography. (A) A mass (arrow) is detected in the left lower lobe in chest CT; (B,C) an aberrant artery (arrow) arises from the descending thoracic aorta.

Figure 3.

The right aberrant blood vessel is detected by tomographic angiography. (A) A mass (arrow) is detected in the right lower lobe (RLL) in chest CT; (B) an aberrant artery (arrow) arises from the celiac artery.

The definitive treatment of PS is surgical excision. Posterolateral thoracotomy is also a safe and effective approach, but is accompanied by greater trauma and more pain (11). VATS, an effective, minimally invasive approach to lung resection, also constitutes an alternative approach to PS treatment. However, very few studies on its use in such treatment have been published to date (4,5). Lobectomy and sub lobectomy are traditionally considered more appropriate surgical options, depending on the location and size of the lesion. We do not agree with the performance of a pneumonectomy unless the ipsilateral lobes have no function because of the high risk of perioperative morbidity or mortality and poor postoperative quality of life. In our study, 55 of the 58 participating patients accepted an anatomic lobectomy, 2 accepted wedge resection, and 1 accepted a left lower lobectomy combined with a lingular segmentectomy.

For experienced surgeons, VATS is a safe and effective procedure for the management of some cases of PS. In the current study, fewer pleural adhesions than expected were encountered, even though recurrent inflammation may lead to pleural reaction and pleural adhesions. VATS is still feasible for most patients with pleural adhesions, unless the adhesions are too dense for dissection by VATS. In that situation, and in the case of any intraoperative difficulty, the surgeon would be wise to convert to thoracotomy. The main intraoperative difficulty lies in identification of the aberrant artery. Aberrant arteries usually hide in the inferior pulmonary ligament and number 1–3 or more (2). The use of an electric coagulation hook and ultrasonic dissector is effective in keeping the surgical field clear of errhysis. Once the aberrant artery has been dissected, ligation using a silk suture can follow, and the artery can be cut by a lineal stapler. For patients with a wider inferior pulmonary ligament, dissection must be performed carefully to ensure that the aberrant artery is not omitted, thereby causing unexpected difficulties. In some cases, circuitous and varicose bronchial arteries can lead to perioperative bleeding if they are not handled appropriately. A titanium clip and ultrasonic dissector are frequently used in our practice to handle this problem.

Our department started using VATS for anatomic lung resection in 2009, but before 2010 we preferred posterolateral thoracotomy because of technical problems. As we now perform more VATS procedures for PS, selection bias may have existed in this study. The more frequent use of hemostatic agents may cause patients treated with VATS to experience less blood loss and have a greater drainage volume and longer chest tube duration than their thoracotomy counterparts.

In conclusion, VATS is a safe, alternative procedure to treat PS in select patients, as determined by experienced surgeons. Simple sequestration without a thoracic cavity or hilum adhesion is a good indication for VATS resection, particularly a VATS anatomic lobectomy. However, a thoracic cavity and hilum adhesion remain a challenge for VATS treatment.

Acknowledgements

Funding: The authors acknowledge supported by the Key Project of Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Plan, China (2014C03032).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Kravitz RM. Congenital malformations of the lung. Pediatr Clin North Am 1994;41:453-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei Y, Li F. Pulmonary sequestration: a retrospective analysis of 2625 cases in China. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:e39-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gezer S, Taştepe I, Sirmali M, et al. Pulmonary sequestration: a single-institutional series composed of 27 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:955-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Pu Q, Ma L, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery for pulmonary sequestration compared with posterolateral thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:557-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen JF, Zhang XX, Li SB, et al. Complete video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for pulmonary sequestration. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:31-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements BS, Warner JO. Pulmonary sequestration and related congenital bronchopulmonary-vascular malformations: nomenclature and classification based on anatomical and embryological considerations. Thorax 1987;42:401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pryce DM. Lower accessory pulmonary artery with intralobar sequestration of lung; a report of seven cases. J Pathol Bacteriol 1946;58:457-67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savic B, Birtel FJ, Tholen W, et al. Lung sequestration: report of seven cases and review of 540 published cases. Thorax 1979;34:96-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S, Ruan Z, Liu F, et al. Pulmonary sequestration: angioarchitecture evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography angiography. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;58:354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franco J, Aliaga R, Domingo ML, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary sequestration by spiral CT angiography. Thorax 1998;53:1089-92; discussion 1088-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagahiro I, Andou A, Aoe M, et al. Pulmonary function, postoperative pain, and serum cytokine level after lobectomy: a comparison of VATS and conventional procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]