Abstract

The E2F transcription factor is a key cell cycle regulator. However, the inactivation of the entire E2F family in Drosophila is permissive throughout most of animal development until pupation when lethality occurs. Here we show that E2F function in the adult skeletal muscle is essential for animal viability since providing E2F function in muscles rescues the lethality of the whole-body E2F-deficient animals. Muscle-specific loss of E2F results in a significant reduction in muscle mass and thinner myofibrils. We demonstrate that E2F is dispensable for proliferation of muscle progenitor cells, but is required during late myogenesis to directly control the expression of a set of muscle-specific genes. Interestingly, E2f1 provides a major contribution to the regulation of myogenic function, while E2f2 appears to be less important. These findings identify a key function of E2F in skeletal muscle required for animal viability, and illustrate how the cell cycle regulator is repurposed in post-mitotic cells.

The transcriptional regulators E2F/Dp play a critical role in cell-cycle regulation, but it is unclear why E2F-deficient flies die. Here, the authors show this is linked to the function of E2F in adult Drosophila skeletal muscle, with the contribution of E2f1 being most important in post-fusion muscle.

The transcriptional regulators E2F/Dp play a critical role in cell-cycle regulation, but it is unclear why E2F-deficient flies die. Here, the authors show this is linked to the function of E2F in adult Drosophila skeletal muscle, with the contribution of E2f1 being most important in post-fusion muscle.

The E2F/DP heterodimeric transcription factors (hereafter referred as E2F) are the key cell cycle regulators and downstream targets of the Retinoblastoma tumour suppressor protein (pRB). Besides their prominent role in tumorigenesis, pRB and E2F are also critical in normal animal development; however, the phenotypes of the E2F and Rb knockout animals are not fully understood1,2,3. The arrangement of the Drosophila Rb pathway is simpler, yet highly analogous to that in mammals4. In flies, there are two E2Fs, an activator E2f1 and a repressor E2f2. Both Drosophila E2Fs heterodimerize with a single obligatory partner Dp, and, therefore, the loss of Dp eliminates all E2F activity and fully phenocopies the E2f1 E2f2 double-mutant phenotype5,6. While most E2F targets are occupied by both E2f1 and E2f2, the relative contribution of each E2F family member to the overall level of expression of the target gene varies. The cell cycle E2F targets are regulated primarily by E2f1-dependent activation, while E2f2 represses the expression of differentiation genes and developmental genes in cycling cells6,7,8.

The streamlined version of the Drosophila E2F/Dp provides a unique opportunity to examine the impact of the complete genetic loss of E2F during development. Unexpectedly, E2f1 E2f2 double-mutants progress normally throughout most of development, without any obvious defects in cell proliferation, differentiation or apoptosis9,10. Eventually, E2F-deficient animals die during pupal stages, and no E2f1 E2f2 double-mutant adults could be recovered, suggesting that E2F is absolutely essential for animal viability. However, the studies on E2F-deficient animals thus far have failed to uncover a defect that could account for their lethality, and, therefore, the essential function of E2F in animal development remains unknown.

Here we show that E2F has an essential function in adult skeletal muscle, which is necessary and sufficient for animal viability. Although E2F is fully dispensable for proliferation of muscle progenitor cells, it is required for muscle growth and myofibrillogenesis. We show that E2F directly regulates the expression of late myogenic genes, with E2f1 providing the major contribution compared with E2f2. Overall, these results illustrate how a cell cycle transcriptional regulator is repurposed in post-mitotic cells to carry out an essential function during myogenic differentiation.

Results

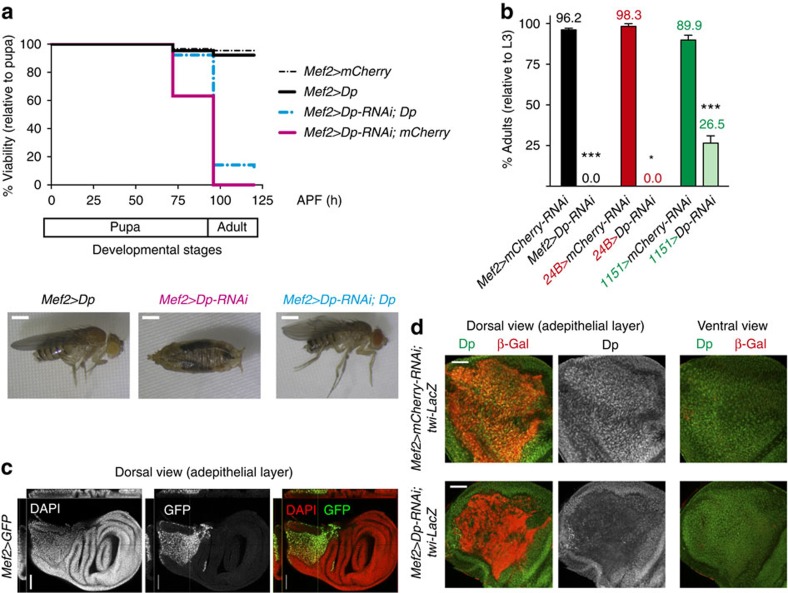

Muscle-specific loss of Dp is lethal

To identify the tissue in which E2F function is required for animal viability, we induced tissue-specific knockdown of Dp using RNA interference (RNAi) and the UAS/GAL4 system. The UAS-Dp-RNAi was crossed to a panel of GAL4 drivers, and animal viability was scored (Supplementary Table 1). Unexpectedly, the depletion of Dp using the myogenic Mef2-GAL4 driver resulted in fully penetrant pupal lethality that mimicked the lethal phenotype of the whole-body Dp mutant (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Table 1). This result was validated using another muscle-specific GAL4 driver, 24B-GAL4, and two independent nonoverlapping UAS-Dp-RNAi lines. Notably, pupal lethality in Mef2>Dp-RNAi animals was partially rescued by co-expression of a UAS-Dp transgene (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1. Muscle-specific inactivation of Dp results in lethality.

(a) The number of viable flies was quantified throughout pupa development. The pan-muscular Mef2-GAL4 driver was used to knockdown Dp by RNAi (UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4, magenta line, n=654 flies). Re-expression of Dp partially rescues the lethality (UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp, cyan-coloured dotted line, n=536 flies). The matching control flies are Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi (dotted black line, n=417 flies) and Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (solid black line, n=523 flies). Data from three independent experiments were plotted. Representative images of adults and pharate pupa are shown at the bottom. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. (b) Lethality was quantified as the percentage of eclosed adults relative to the number of third instar larvae (L3). The GAL4 drivers Mef2-GAL4 (black bar, n=239 and 173 flies), 24B-GAL4 (red bar, n=64 and 71 flies) and 1151-GAL4 (green bar, n=159 and 158 flies) were crossed either to UAS-mCherry-RNAi or UAS-Dp-RNAi. Mean±s.e.m. Data from at least two independent experiments were plotted, Mann–Whitney test. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001. (c) The expression of Mef2-GAL4 is restricted to the adepithelial cells of late third instar larval wing discs. Several confocal images were taken in a z-stack. Orthogonal confocal cross-sections are presented on the top and left side of each image. Scale bar, 100 μm. (d) Wing discs of late third instar larvae stained with anti-Dp antibody (green) and labelled with twi-lacZ marker (β-Gal, red). Although Dp is localized in nuclei throughout the wing disc, Dp protein was specifically depleted only in the adult myoblast of UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4 (bottom panel) compared with control Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi (top panel). Two different confocal planes of the discs are shown: the dorsal view, which contains the adepithelial layer (left panel), and the ventral view (right panel). The experiment was repeated twice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

In Drosophila, the adult skeletal muscles are formed during pupal development11. The myoblasts, also known as adult muscle precursors, proliferate in the adepithelial layer at the dorsal proximal side of the wing imaginal disc that give rise to the adult flight muscles12. In late third instar larvae, these proliferating myoblasts can be visualized by the expression of Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2 (Mef2) and Twist bHLH (Twi) transcription factors13,14, using Mef2-GAL4-driven GFP (green fluorescent protein) and twi-lacZ markers, respectively (Fig. 1c,d). The efficiency of muscle-specific Dp knockdown was confirmed by staining wing imaginal discs of Mef2>Dp-RNAi; twi-lacZ animals with Dp and β-Gal antibodies. Dp was depleted specifically in myoblasts (β-Gal-positive) but not in the adjacent epithelial cells of the wing imaginal disc (β-Gal-negative; Fig. 1d).

Both Mef2-GAL4 and 24B-GAL4 are broadly expressed in all muscle types throughout development. In contrast, 1151-GAL4 is expressed exclusively in adult muscle precursors, developing adult skeletal muscles and tendon cells for the jump muscles, while it is not expressed in larval, cardiac or visceral muscles15,16,17,18. Inactivation of Dp using 1151-GAL4 resulted in a threefold reduction in the number of eclosing adults with lethality occurring at the pupal stage (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the 1151>Dp-RNAi escapers were significantly defective in their ability to fly and jump (Supplementary Table 1), which indicates impaired adult skeletal muscle function and development19. Consistently, depletion of Dp with either Mhc.F3-580-GAL4 or Act88F-GAL4, which are expressed in differentiating indirect flight muscles, resulted in similar flight/jump defects (Supplementary Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest an essential role for E2F in adult skeletal muscles, which is crucial for animal viability.

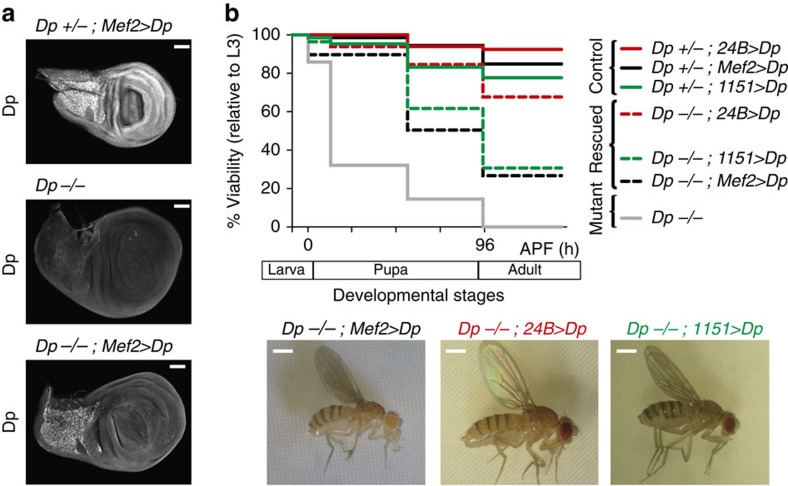

Muscle-specific expression of Dp rescues Dp-mutant lethality

Results described above raise the possibility that the lethality in Dp mutants is due to the loss of Dp function in the muscle. If this is the case, then providing Dp function in muscles should be sufficient to rescue the whole-body Dp mutant, and permit the completion of development to adulthood. We expressed a UAS-Dp transgene in the Dp null mutant animals (Dp−/−) using the Mef2-GAL4 driver. Dp−/− animals were generated by crossing a known Dp null allele, Dpa3 (refs 5, 10), to a deficiency that removes the entire Dp gene, Df(2R)Exel7124. The muscle-specific expression of Dp in Dp−/−; Mef2>Dp animals was confirmed by staining wing discs with the Dp antibody. Dp expression was indeed restricted to adult myoblasts in the adepithelial layer and was completely absent in the imaginal disc (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Expression of Dp in adult skeletal muscles rescues the lethality of the whole-body Dp−/− null mutant animals.

(a) Confocal sections of the adepithelial cells show that Dp expression is restricted to the adult myoblasts of the rescued animals (Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp, bottom panel), compared with the Dp-mutant (Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124, middle panel), and control (Dpa3/+;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp, top panel). Representative images are shown. Scale bar, 0.5 μm. (b) The number of viable flies was quantified throughout development. Dp mutants, Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124 (grey line, n=445), are lethal at mid-pupa stage. The lethality is partially rescued by overexpressing UAS-Dp in the muscle using either Mef2-GAL4 (black dotted line, n=204 flies), 24B-GAL4 (red dotted line, n=65 flies) or 1151-GAL4 (green dotted line, n=72 flies). Control genotypes are Dpa3/+; Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (black solid line, n=337 flies), Dpa3/+;24B-GAL4/UAS-Dp (red solid line, n=66 flies) and 1151-GAL4;Dpa3/+;UAS-Dp (green solid line, n=113 flies). At least two independent experiments were performed using at least six replicates per genotype each. The genotypes Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp, Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124;1151-GAL4/UAS-Dp, and their respective controls were confirmed by single-fly PCR and by sequencing the Dp-mutant allele in individual flies. Representative images are shown at the bottom. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. See also Supplementary Fig. 1.

Strikingly, while all Dp null mutants died during pupal development, 27% of Dp−/−; Mef2>Dp animals survived to adulthood (Fig. 2b). The rescued adult flies did not show any gross morphological defects, although they displayed a subtle rough eye phenotype and sterility, the latter likely reflects the known requirement of Dp in oogenesis20,21. Another muscle-specific driver, 24B-GAL4, provided an even stronger rescue (68% of rescued Dp−/−; 24B>Dp adults, Fig. 2b). The lethality of the Dp mutant was also rescued when Dp expression was limited to adult myoblasts and adult skeletal muscles using 1151-GAL4 (31% of rescued Dp−/−;1151>Dp adults, Fig. 2b). We confirmed that the rescue was not due to leaky expression of Mef2-GAL4 and 24B-GAL4 drivers in non-related muscle tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1).

These results provide strong genetic evidence that the lethality in the Dp mutant was not caused by the requirement for E2F/Dp in the entire organism, but rather was due to the requirement of E2F/Dp function in adult skeletal muscle. Therefore, to understand why E2F/Dp is so important in this tissue, we examined its role during adult skeletal muscle development.

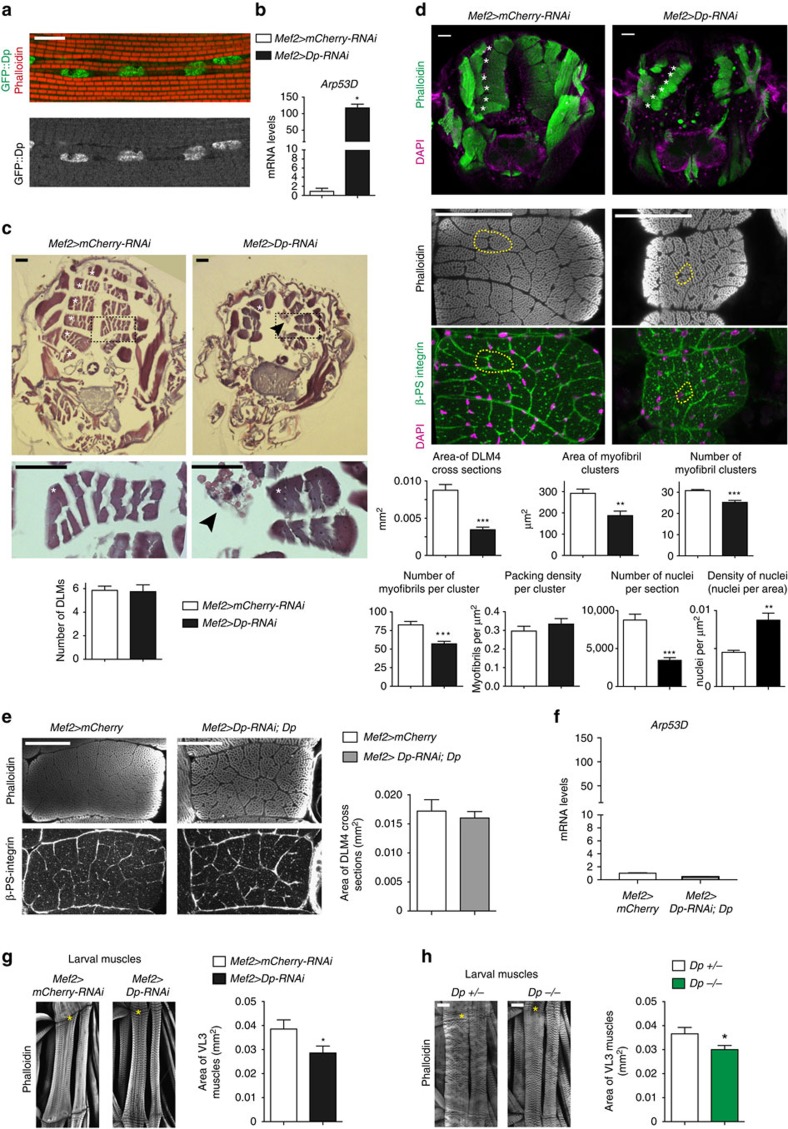

Knockdown of Dp reduces the size of adult skeletal muscles

Staining with anti-Dp antibody and the Dp[GFP] reporter line22 revealed that Dp is broadly expressed in various muscle types (Supplementary Fig. 2A,B). High Dp levels were detected in the nuclei of larval body wall muscles, in cardiac and pericardial nuclei of the larval cardiac tube, in adult muscle precursors and in the indirect flight muscles of adult flies (Supplementary Fig. 2C–F) and pharate pupa (Fig. 3a). Since Dp mutants die at an early pupal stage, we examined Mef2>Dp-RNAi animals at the time point immediately preceding the lethal stage. The efficiency of Dp depletion was confirmed by measuring the expression of a known E2F target gene, Arp53D, which is de-repressed in response to E2F inactivation7 (Fig. 3b). The indirect flight muscles constitute more than 70% of the entire skeletal muscle mass and comprises two groups of muscles: dorsal longitudinal muscles (DLMs) and dorsal ventral muscles23. The architecture of DLMs was analysed by staining the transverse paraffin-embedded tissue sections with haematoxylin and eosin dyes. Most Mef2>Dp-RNAi pharates displayed six DLMs per hemithoraces (Fig. 3c), indicating that the main steps of muscle development are unaffected. However, each DLM cross-section area was significantly thinner compared with the control (white asterisks, Fig. 3c,d) suggesting that the overall muscle mass is reduced.

Figure 3. Loss of Dp reduces the size of larval and adult skeletal muscles.

(a) Dp::GFP localizes in DLM nuclei of DpGFP pharates. Scale bar, 10 μm. See Supplementary Fig. 2. (b) Arp53D expression in flight muscle is de-repressed in Dp knockdown. RT–qPCR, mean±s.e.m., N=3 samples per genotype, Mann–Whitney test, *P<0.05. (c,d) Muscle size is reduced in Dp-depleted muscles. Transverse sections of pharate thoraces (ventral to the bottom). Each hemithorax contains six DLM (white asterisks, left panel). Scale bar, 50 μm. (c) Paraffin-embedded sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin. DLM4 (dashed black boxes) magnified at the bottom panel. Black arrowheads point the aggregates/clumps. Quantification of total number of DLMs per hemithorax, mean±s.d., N=21, 16 per genotype, Mann–Whitney test, P>0.05. (d) Sections stained with Phalloidin and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; top panel). DLM 4 stained with Phalloidin (middle panel), β-PS integrin to mark the plasma membrane and DAPI (bottom panel). Cluster of myofibrils is outlined (yellow dashed line). Quantification of DLM4 cross-section area per fly (mm2). Area of myofibril clusters, total number of myofibril cluster, total number of myofibrils per cluster, myofibril density per cluster area (μm2), total number of nuclei and density of nuclei per DLM4 area (μm2) are quantified per DLM4, mean±s.e.m., N=8 per genotype, t-test with Welch's correction, **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Three independent experiments. (e) Muscle size is rescued in thoraces of 2- to 5-day-old UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp adults compared with Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry. Sections stained with Phalloidin and β-PS integrin. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification of DLM4 cross-section area per fly (mm2), mean±s.e.m., n=8, 10 per genotype, t-test with Welch's correction, P>0.05. Two independent experiments. (f) Arp53D expression in flight muscles is rescued. Same genotype as in e. Mean±s.e.m., N=3 samples per genotype, Mann–Whitney test, P>0.05. (g,h) Third instar larval body wall muscle area is reduced in (g) Dp-depleted muscles and (h) in Dp−/− mutant. Body wall muscles VL3 (asterisks) and VL4 stained with Phalloidin. Anterior is to the top. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification of VL3 muscle area, mean±s.e.m., unpaired t-test with Welch's correction, P<0.05. Three independent experiments. (g) n=10, 11, (h) n=12, 10 per genotype. Genotypes (b–d,g) Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi and UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4, (h) Dpa3/+ and Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124.

The structure of DLMs closely parallels that of vertebrate skeletal muscles. In DLMs, myofibrils are organized in clusters, with each cluster being surrounded by a membrane (dashed line in Fig. 3d). The area of each myofibril cluster is determined by the number of myofibrils and their packing density within the cluster. Thus, the small DLM size could be due to a reduction in the number of clusters or the cluster size. Frozen transverse tissue sections of thoraces were co-stained with Phalloidin and β-PS integrin antibody to visualize the myofibrils and the surrounding membrane, respectively (Fig. 3d). The overall structure and organization of DLM3 and DLM4 was examined. The number of clusters per DLM, the area of each cluster and the number of myofibrils per cluster were reduced in Mef2>Dp-RNAi compared with control. However, the packing density remained unaffected (Fig. 3d). Consistently, the number of nuclei per DLM was reduced. Importantly, the reduced muscle size was largely rescued by the re-expression of the UAS-Dp transgene in the Dp-depleted muscle of adult animals (Fig. 3e). As expected, Arp53D became fully repressed, confirming that Dp function is restored in Mef2>Dp-RNAi;UAS-Dp (Fig. 3f). Thus, we concluded that Dp-deficient muscles are smaller because of a reduction in the number of myofibrils per DLM without changes in muscle architecture.

To determine whether Dp depletion affects the size of other types of muscles in Drosophila, body wall preparations of third instar larvae were stained with phalloidin, and the size of the ventral longitudinal 3 (VL3) muscle was measured. As in the flight muscles, the Dp-depleted larval muscles were thinner (Fig. 3g). Importantly, the size of VL3 was reduced in Dp−/− mutant to a similar extent to Mef2>Dp-RNAi larvae (Fig. 3h). Thus, we concluded that the reduced muscle size was specifically the result of Dp depletion in Mef2>Dp-RNAi larvae because it was also observed in mutant animals. However, the reduction in larval muscle size was relatively subtle, thus suggesting that E2F plays a minor role in larval skeletal muscle development in contrast to its requirement in adult skeletal muscles.

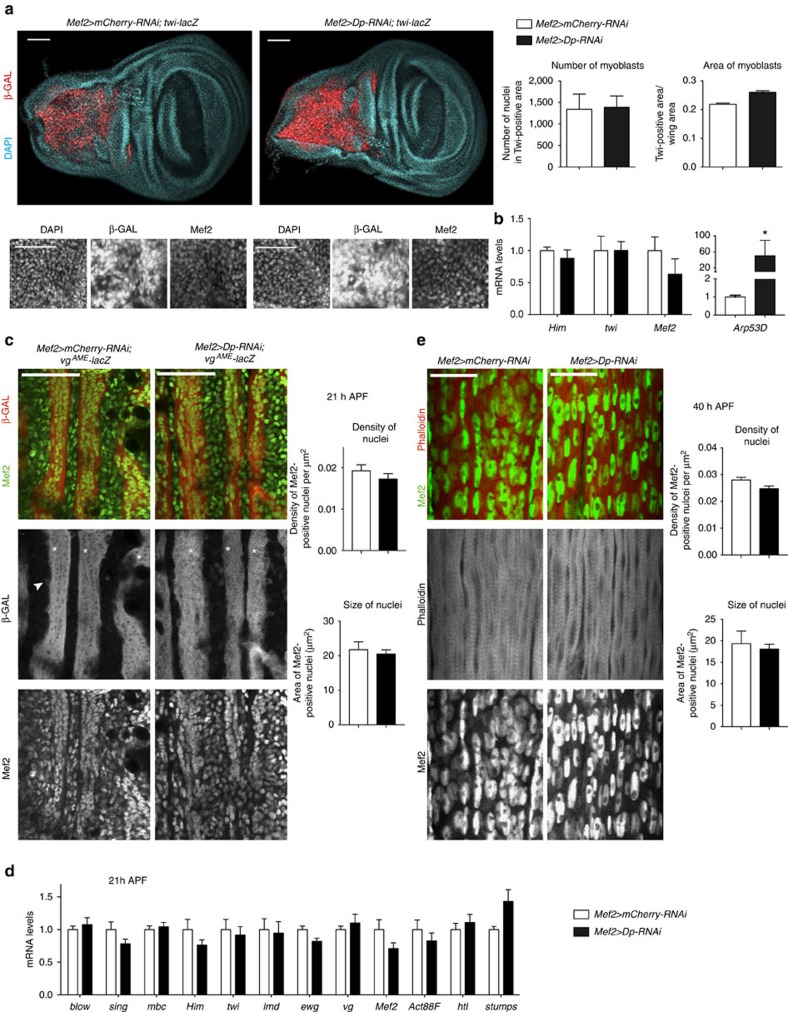

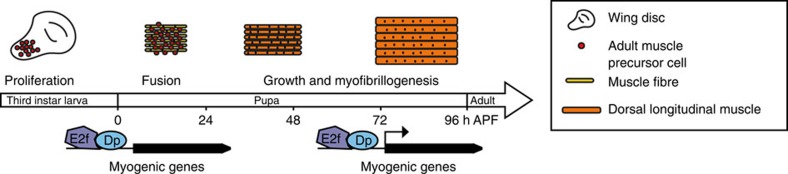

Dp depletion does not alter myoblast proliferation or fusion

Drosophila muscle development occurs in a highly ordered manner that is tightly coordinated with the myogenic transcription programme. Adult myoblasts proliferate during larval stages within the adepithelial layer of the wing imaginal disc. In early pupae, myoblasts migrate and fuse into multinucleated myotubes. Fusion is completed by 36 h APF (after pupa formation), and, during the remainder of pupal development, DLMs increase in size because of the addition of myofibrils, and the assembly of the sarcomeres23,24,25. This late stage of myogenesis is characterized by a high level of expression of genes encoding structural and contractile proteins, which supports the increase in muscle mass. Thus, the final muscle size is determined by (1) the number of myoblasts and their fusion competence, (2) the proper assembly of myofibrils and (3) the ability of the muscle to grow. To understand why the loss of Dp results in reduced muscle size, we examined the effect of Dp depletion on each step of myogenesis.

We began by analysing proliferation in Dp-depleted adult myoblasts. The adult myoblasts within the adepithelial layer of Mef2>Dp-RNAi and control discs were blindly quantified using twi-lacZ reporter and Mef2 antibody as myoblast-specific markers (Fig. 4a). The number of Dp-depleted myoblasts and the corresponding area were indistinguishable from that of control (Fig. 4a). Consistently, the expression of genes encoding myogenic regulators, twi, Holes-in-muscles (Him) and Mef2, was not significantly different in Dp-depleted adult myoblasts compared with control (Fig. 4b). Dp depletion was efficient because the E2F target Arp53D was strongly de-repressed (Fig. 4b). Thus, the small size of Dp-deficient adult muscles was not because of a reduction in the pool of adult myoblasts.

Figure 4. Loss of E2F does not affect myoblast proliferation or fusion at the onset of myotube formation.

(a) Myoblast area and number are not altered. Confocal images of late third instar wing discs stained with anti-β-GAL (twi-lacZ), anti-Mef2 antibody and DAPI. Z-stack-projected images of adepithelial area were magnified. Quantification of total number of nuclei in Twi-positive area using DAPI staining, and Twi-positive area relative to total wing area, mean±s.e.m., n=14, 10 wing discs per genotype, t-test with Welch's correction, P>0.01. Two independent experiments. (b) The expression of myoblast-specific genes in wing discs is not affected. Expression of twi, Holes-in-muscles (Him) and Mef2 genes quantified by RT–qPCR. Arp53D was de-repressed in Dp-depleted wing discs. Mean±s.e.m., N=3 and 5 samples per genotype, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), P>0.05 (left panel) and Mann–Whitney test, *P<0.05 (right panel). (c) The onset of myotube differentiation proceeds normally. Developing DLMs (asterisks) at 21 h APF stained with the reporter vgAME-lacZ to mark the onset of myotube formation and anti-Mef2 antibody. Arrowhead points to a fusion event. Anterior is to the top. Quantification of the total number of Mef2-positive nuclei per image (μm2), the area of Mef2-positive nuclei (μm2), mean±s.e.m., N=9 thoraces per genotype, t-test with Welch's correction, P>0.05. Three independent experiments. (d) The expression of myogenic genes in developing flight muscles at 21 h APF is normal. The genes measured are blown fuse (blow), singles bar (sing), myoblast city (mbc), Holes-in-muscles (Him), twist (twi), lame duck (lmd), erect wing (ewg), vestigial (vg), Mef2, Act88F, htl and stumps. mean±s.e.m., N=4 independent samples per genotype, two-way ANOVA, P>0.05. (e) Myoblast fusion to developing DLMs is not grossly altered. Developing DLMs at 40 h APF stained with Phalloidin to mark early myofibrils and anti-Mef2 antibody. Anterior is to the top. Quantification of the total number of Mef2-positive nuclei per area (μm2), the area of Mef2-positive nuclei (μm2), Mean±s.e.m., N=8 thoraces per genotype, t-test with Welch's correction, P>0.01. Two independent experiments. Genotypes are Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi and UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4. Scale bar, 50 μm (a–c), and 20 μm (e).

Next, developing myotubes were visualized with the vestigial adult muscle enhancer (vgAME-lacZ) reporter26 at 21 h APF when wild-type migrating myoblasts are undergoing fusion. Dp-depleted myotubes properly activated vgAME-lacZ expression (white asterisks, Fig. 4c) and, in several cases, expression of vgAME-lacZ was detected in individual myoblasts immediately before fusion similarly to that observed in control (arrowhead, Fig. 4c). Counting the number of Mef2-positive nuclei in the nascent myotubes and surrounding myoblasts revealed a subtle, yet not statistically significant, reduction in Mef2>Dp-RNAi (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that at 21 h APF both migration and fusion proceeded normally.

This conclusion was corroborated using quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR (qRT–PCR). The expression of genes encoding fusion proteins (blow, sing, mbc), myogenic regulators (Him, twi, lame duck (lmd), Mef2, erect wing (ewg), vg), muscle progenitor specification genes (heartless (htl), stumps) and the structural gene Actin 88F (Act88F) was normal at 21 h APF in Dp-depleted muscles (Fig. 4d).

To determine whether all migrating Dp-depleted myoblasts properly completed fusion to developing DLMs, we examined DLMs at 40 h APF, when fusion is complete. The multinucleated DLMs were stained with Phalloidin to reveal the overall architecture, and with Mef2 antibody to mark individual nuclei. The number of nuclei in Dp-depleted DLMs was slightly but not significantly reduced (Fig. 4e). Thus, knockdown of Dp does not affect the overall pool of myoblasts or their ability to migrate and fuse properly.

Growth is defective in Dp-depleted adult skeletal muscles

The development of the indirect flight muscles culminates in myofibrillogenesis, during which actin and myosin filaments are assembled to form myofibrils, which in turn contain the highly ordered repetitive contractile units known as sarcomeres. Sarcomeres are composed of parallel thick and thin filaments. Thin filaments from neighbouring sarcomeres are crosslinked in the Z-disc, and thick filaments are crosslinked in the M-line. The indirect flight muscles express specific proteins, such as Flightin (Fln), and muscle-specific isoforms of structural proteins, such as Act88F and Troponin C isoform 4 (refs 27, 28, 29). Myofibrillogenesis is accompanied by a dramatic increase in muscle size. The robust expression of muscle structural genes is needed to support muscle growth during the remainder of pupal development.

The DLMs were dissected from pharate adults (96 h APF), and longitudinal sections were stained with phalloidin to visualize myofibril organization. Dp-depleted muscle showed a mild disorganization in the myofibril structure. The assembly of sarcomere was assessed using a GFP-tagged Mhc isoform, weeP26, that localizes to two foci flanking the M-line at the core of the sarcomere30. The localization of weeP26 in Dp-depleted muscles was more diffuse and the intensity of the signal was reduced compared with control (Fig. 5a). The Z-line constitutes a critical anchoring point for thin filaments and can be visualized using the Sls-GFP reporter30. Notably, the pattern of Z-lines in Dp-depleted DLMs was less definitive than in control (Fig. 5b). In addition, myofibril width was significantly reduced in Dp-depleted DLMs, as shown by the plot profile of phalloidin intensity over distance (Fig. 5c), suggesting an impaired recruitment of thick filaments. Interestingly, nuclei were larger in Dp-depleted muscles than in control (Fig. 5d). Thus, Dp-depleted muscles formed sarcomeres properly; however, the sarcomere structure was less pronounced, which might result from stoichiometric imbalance among sarcomere components31.

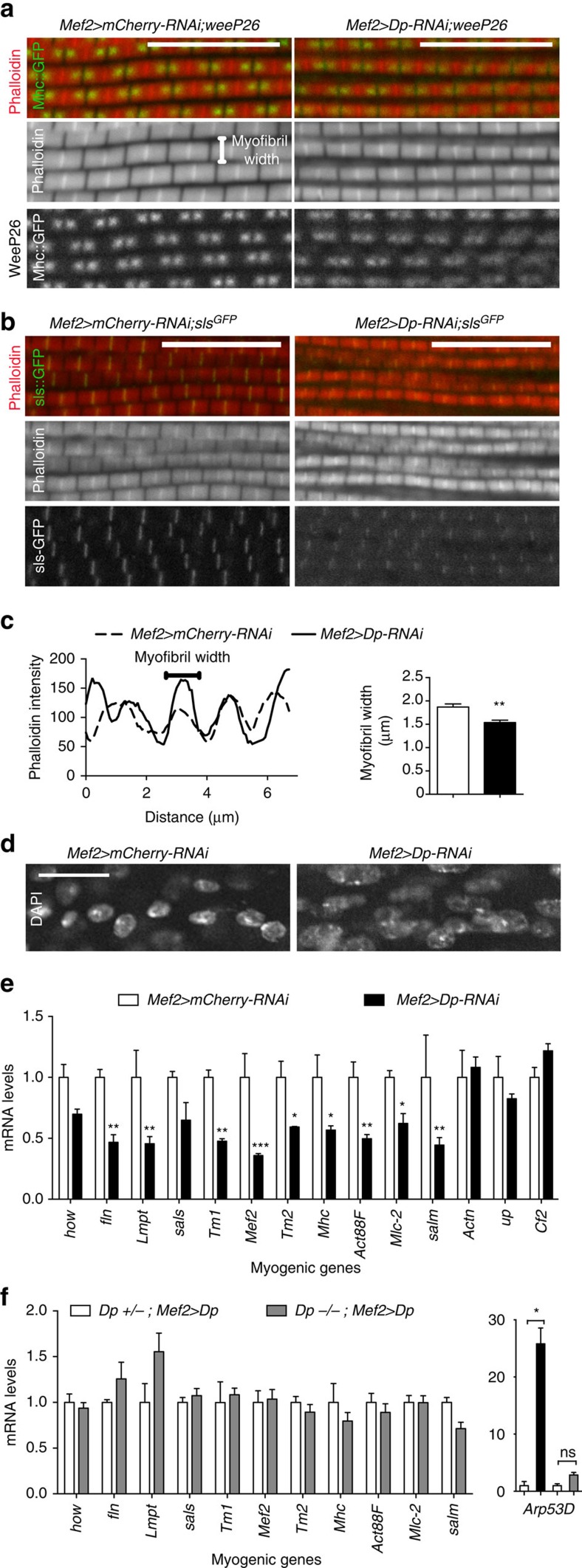

Figure 5. E2F controls myofibrillogenesis in flight muscles by regulating myogenic gene expression.

(a–c) Myobrils and sarcomeric proteins are slightly misassembled in Dp-depleted muscles at the pharate stage. Confocal images of DLMs in a sagittal view stained with Phalloidin (red) in a GFP-tagged splice variant Mhc-IFM19 background (weeP26), to mark A-band structure (a), or in an Sls-GFP background to mark Z-band structure (b). Scale bar, 5 μm. (c) Profile plot of phalloidin intensity over distance. A line perpendicular to myofibril orientation was drawn to determine the number of myofibrils per distance. Quantification of myofibril width (μm), mean±s.e.m., N=8 and 7 hemithoraces per genotype, t-test with Welch's correction, **P<0.01. (d) Nuclei are enlarged in Dp-depleted muscles. Confocal images of DLMs in a sagittal view stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. (e,f) Muscle-specific gene expression is compromised in Dp-depleted flight muscles at the pharate stage, and rescued by overexpressing Dp only in muscles of Dp-mutant background. Muscle genes are how, fln, Lmpt, sals, Tm1, Mef2, Tm2, Mhc, Act88F, Mlc2, salm, Actn, Cf2 and upheld (up, TpnT or wupB). Mean±s.e.m., N=3 independent samples per genotype, two-way ANOVA (e), Kruskal–wallis test (f), *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Genotypes are (a–e) Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi (left panel, white bar) and UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4 (right panel, black bar), and (f) Dpa3/+; Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (white bar) and Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (grey bar).

Since myofibrillogenesis and the accompanying muscle growth depend on robust expression of structural genes, we examined the level of myogenic transcripts in flight muscles of pharate using qRT–PCR. The expression of genes encoding structural and contractile proteins, such as Myosin heavy chain (Mhc), fln, Tropomyosin 1 (Tm1), Tropomyosin 2 (Tm2), Myosin light chain 2 (Mlc2), sarcomere length short (sals) and Act88F, and myogenic regulators, such as held out wings (how), Limpet (Lmpt), Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (Mef2) and spalt major (salm), were markedly reduced (Fig. 5e). We confirmed the decreased expression of these genes with an independent UAS-Dp-RNAi transgene (Mef2>Dp-RNAi-TRiP, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Importantly, the defect in gene expression was fully rescued by muscle-specific re-expression of the UAS-Dp transgene in the Dp−/− mutant background (Dp−/−; Mef2>Dp, Fig. 5f, grey box) and was partially rescued in the Dp-RNAi background (Mef2>Dp-RNAi;UAS-Dp, Supplementary Fig. 4). In each experiment, we monitored the expression of Arp53D to ensure the efficient depletion of Dp in RNAi experiments and the rescue following Dp re-expression (Supplementary Fig. 3B and Figs 3f and 5f). Not every structural gene was reduced following Dp knockdown, such as upheld (or Troponin T) and α-actinin (Actn; Fig. 5e). Similarly, the myogenic transcription factor Chorion factor 2 (Cf2), which represses the expression of Act88F in indirect flight muscles32, was unaffected (Fig. 5e).

These results suggest that the loss of Dp does not alter muscle development, but rather affects the growth of muscles, which is likely to be due to the reduced expression of a subset of late myogenic genes.

Mitochondria are abnormal in Dp-depleted muscles

During DLM growth, mitochondria undergo extensive fusion, increase in size33 and become large and tubular as revealed by mitogFP marker (Fig. 6a). Dp-depleted muscles failed to properly remodel mitochondria, which remained thin and elongated, resembling mitochondria at earlier time points of muscle development33. E2F/Dp was shown to regulate mitochondrial function by directly controlling the expression of mitochondria-associated genes in the eye34. In Dp-depleted muscle, the expression of mitochondria-associated E2F target genes, COX5A, ND-B17.2 and Idh (ref. 34), were downregulated (Fig. 6b). Thus, the role of E2F in the regulation of mitochondria is conserved in Drosophila skeletal muscle.

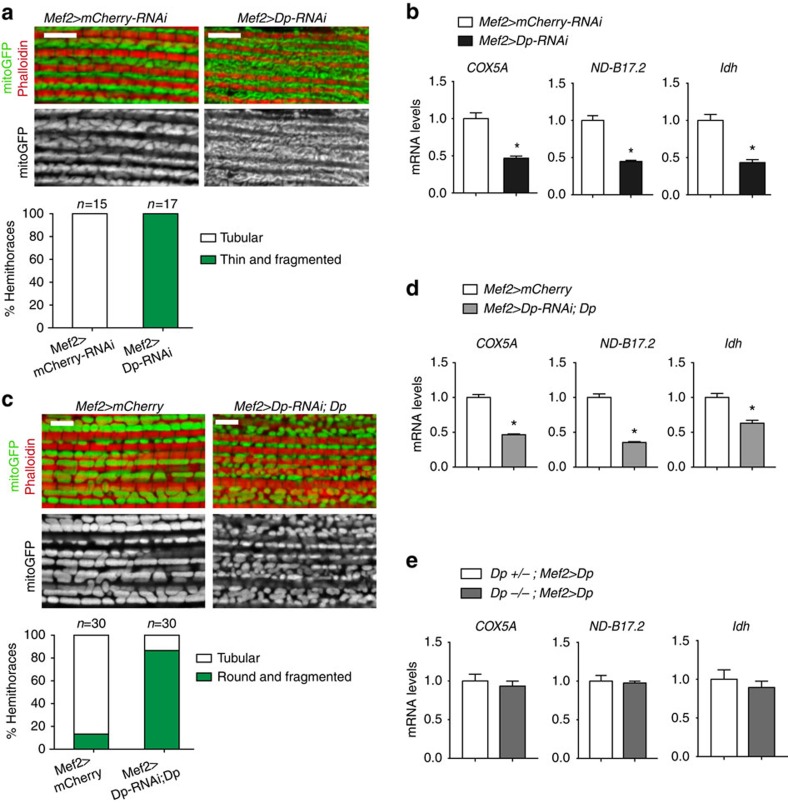

Figure 6. Mitochondria are abnormal in Dp-depleted muscles.

The structure of mitochondria (a) and the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes (b) are compromised in Dp-depleted muscles at the pharate stage. Although mitochondrial structure (c) and gene expression (d) are not fully reversed in the partially rescued adult flies (2- to 5-day-old), gene expression is fully restored in the rescued pharates that express Dp in Dp-mutant background (e). (a,c) Confocal images of DLMs stained with Phalloidin (red) and mitoGFP (green) to label mitochondria in a sagittal view. Scale bar, 5 μm. Quantification of hemithoraces displaying (a) round/tubular or thin/fragmented mitochondria shape, N=15 and 17 hemithoraces per genotype, (c) tubular or round/fragmented mitochondria shape, n=30 hemithoraces per genotype. Two independent experiments were performed. (b,d,e) The expression of the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5A (Cox5A, also known as CoVa), NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) B17.2 subunit (ND-B17.2, CG3214) and Isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh, CG6439), quantified using RT–qPCR in indirect flight muscles of pharate pupae (b,e) and adult flies (d). Mean±s.e.m., N=3 independent samples per genotype, Mann–Whitney test, *P<0.05. Genotypes are (a,b) Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi (left panel and white bar) and UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4 (right panel and black bar), (c,d) Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry (left panel and white bar) and UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (right panel and grey bar), and (e) Dpa3/+; Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (white bar) and Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Dp (grey bar).

We analysed mitochondrial morphology in rare Mef2>Dp-RNAi;UAS-Dp animals that were rescued to adulthood by muscle-specific expression of Dp (Fig. 1a) and no longer displayed the muscle growth defect (Fig. 3e). Interestingly, the mitochondrial network in Mef2>Dp-RNAi;UAS-Dp adults remained abnormal (Fig. 6c). Consistent with persistent mitochondrial defects, the expression of mitochondria-associated genes also remained low (Fig. 6d). These data suggest that both the muscle growth defect and the lethality of Mef2>Dp-RNAi animals can be rescued, at least partially, without fully suppressing the mitochondrial defect. Notably, in the Dp−/− mutants that were rescued to adulthood by expression of UAS-Dp with Mef2-GAL4, the expression of mitochondria-associated genes was fully restored (Fig. 6e). The rescue of mitochondria network correlated with animal viability rescue, as ∼30% of Dp−/−; Mef2>Dp reached the adult stage versus 10% of Mef2>Dp-RNAi; Dp (Figs 1a and 2b). Thus, the rescue of muscle growth defects and mitochondrial function is needed in Dp-deficient animals to survive to adulthood.

E2F directly regulates the expression of late myogenic genes

To investigate the role of the E2F/Rb pathway in regulating the expression of late myogenic genes, we selected genes that were downregulated in Dp-deficient muscles and contained putative E2F-binding sites in the proximity of the transcription start site. Chromatin was isolated from pharate pupa and was subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–qPCR. Significantly, upstream regions of myogenic genes, such as how, fln, Lmpt, sals, Tm1 and Mef2, were specifically enriched with E2f1, E2f2, Dp and Rbf antibodies in comparison with a nonspecific antibody (IgG, Fig. 7a). No enrichment was detected for the negative site, which did not contain predicted E2F-binding sites. Some myogenic genes, such as Tm2, did not show any enrichment upstream the transcription start site (Fig. 7a), suggesting that either their expression is indirectly regulated by E2F or E2F binds to a different region from the one tested using ChIP–qPCR.

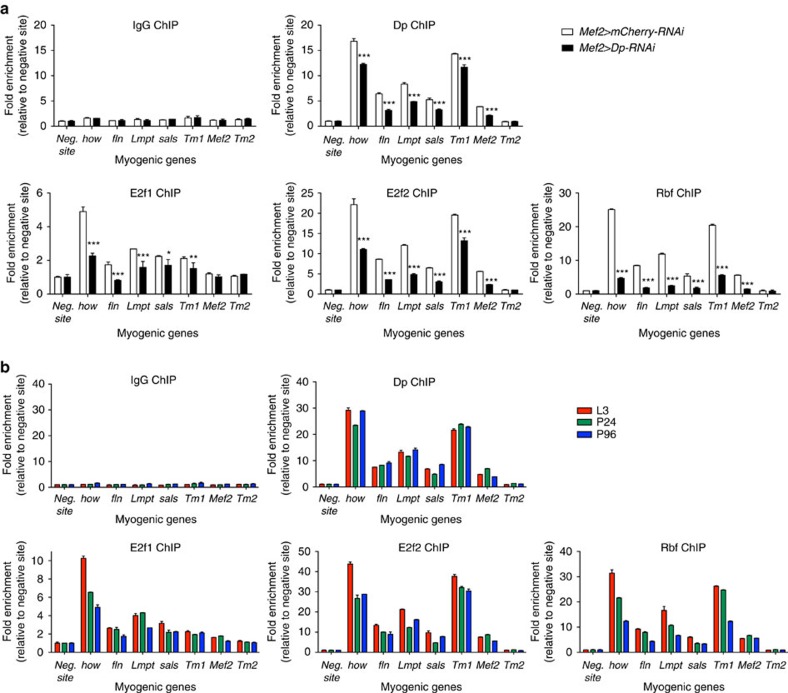

Figure 7. The E2F/Rb pathway directly controls myogenic gene expression throughout development.

E2f1, E2f2, Dp and Rbf proteins are enriched upstream several myogenic genes in a Dp-dependent manner (a), and throughout development (b). Chromatin from pharate pupae (P96, a,b), third instar larvae (L3, b) and early pupae (P24, b) were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against Dp (top right panel), E2f1 (bottom left panel), E2f2 (bottom middle panel) or Rbf (bottom right panel), and compared with nonspecific control antibodies (top left panel). Muscle genes are how, fln, Lmpt, sals, Tm1, Mef2 and Tm2. The negative site does not contain predicted E2F-binding sites. The qPCR data are shown as fold enrichment relative to the negative site for each ChIP sample. Mean±s.d., n=2 replicates, two-way ANOVA, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Genotypes are (a) Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi (white bar) and UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4 (black bar), and (b) Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi.

Next, we performed ChIP–qPCR using chromatin isolated from Mef2>Dp-RNAi pharate adults, in which Dp was depleted exclusively in muscles, while the remainder of the animals expressed normal levels of endogenous Dp. The muscle-specific depletion of Dp resulted in significantly reduced enrichment of E2f1, E2f2, Dp and Rbf on the myogenic genes (Fig. 7a). This suggests that E2F/Dp is present as a complex, and that the recruitment of Rbf is E2F-dependent.

Since the expression of the contractile and structural genes is restricted to a narrow window during mid to late pupal development, we examined the occupancy of E2F/Dp/Rbf on these genes during different time points in development. Chromatin was isolated from third instar larva, early pupa (24 h APF) and pharate (96 h APF) animals. Notably, E2f1, E2f2, Dp and Rbf were highly enriched at these promoters even before the activation of fln, Lmpt and Tm1 gene expression (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that, although E2F/Dp is required for the expression of several myogenic genes, it is insufficient to activate their expression by itself. Therefore, other myogenic transcription factors are operating at this point to induce their expression.

E2f1 provides a major contribution to skeletal muscle growth

During cell proliferation, E2f1 and E2f2 act antagonistically to each other, with E2f1 being an activator and E2f2 acting as a repressor7,9. The loss of E2f1 blocks cell proliferation and results in larval lethality35,36; however, this defect is rescued by the E2f2 mutation as E2f1 E2f2 double mutants proliferate normally and survive until the pupal stage9. To determine the relative contribution of E2f1 and E2f2 in muscle, each E2F family member was inactivated singularly, and the impact on myogenesis was investigated. Since E2f1 mutants are lethal at larval stages, we used UAS-E2f1-RNAi37. As expected, depletion of E2f1 in proliferating myoblasts with Mef2-GAL4 significantly impaired proliferation and resulted in early pupal lethality before muscle differentiation. Therefore, E2f1 was depleted specifically in the post-fusion indirect flight muscles with a late myogenic Act88F-GAL4 driver17. The efficiency of E2f1 depletion was confirmed using qRT–PCR (Fig. 8a).

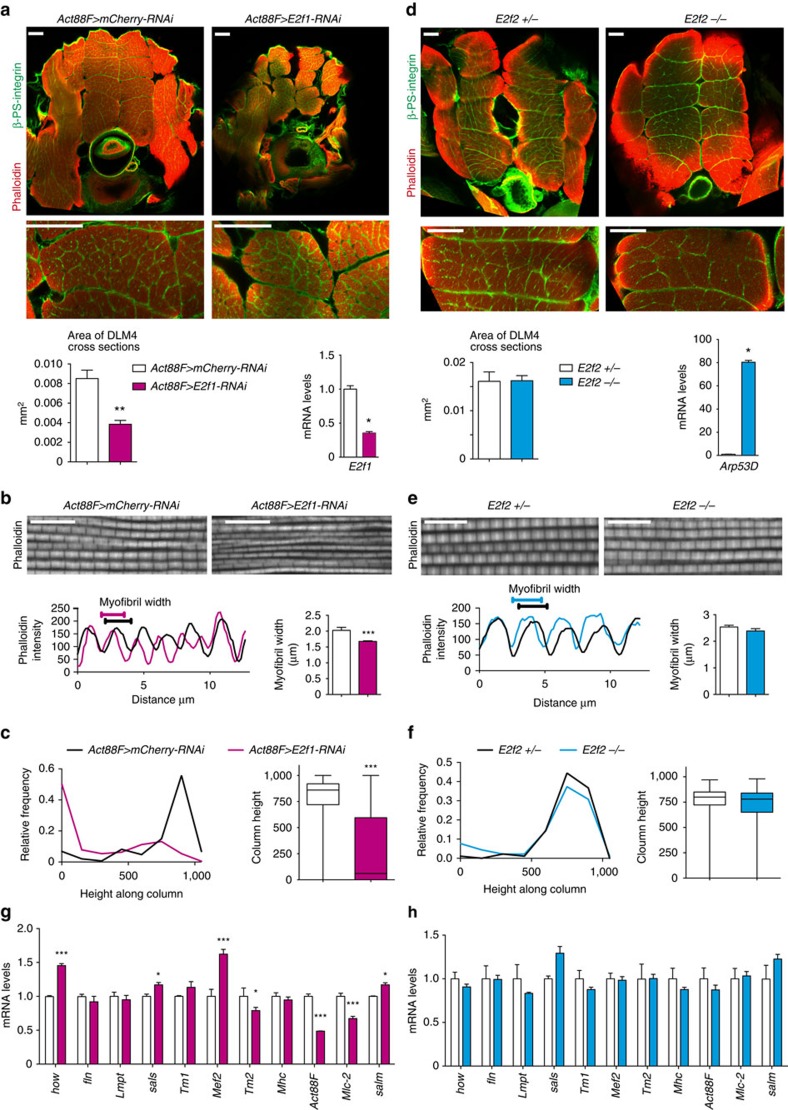

Figure 8. E2f1 is a major contributor to muscle growth and function in post-fused indirect flight muscles.

(a,d) Muscle size is reduced in E2f1-depleted muscles (Act88F>E2f1-RNAi), whereas E2f2 mutant muscles are normal. Transverse sections stained with Phalloidin and β-PS integrin (ventral to the bottom, top panel). DLM4 is magnified (middle panel). Scale bar, 50 μm. Representative images are shown. Quantification of DLM4 cross-section area per fly (mm2), mean±s.e.m., Mann–Whitney test, **P<0.01. (a) n=6, (d) n=3,4 flies per genotype. Expression of E2f1 (a, bottom right panel) and Arp53D (b, bottom right panel) in flight muscles measured by RT–qPCR. Mean±s.e.m., N=3 independent samples per genotype, Mann–Whitney test, *P<0.05. (b,e) Myofibril width is slightly reduced in Act88F>E2f1-RNAi, whereas in E2f2 mutant it is normal. Confocal images of DLMs in a sagittal view stained with Phalloidin. Scale bar, 10 μm. Profile plot of phalloidin intensity over distance (bottom left panel). A line perpendicular to myofibril orientation was drawn to determine the number of myofibrils per distance. Quantification of myofibril width (μm; bottom right panel), mean±s.e.m., Mann–Whitney test, **P<0.01. (b) n=7,8, (e) n=6 hemithoraces per genotype. (c,f) Flight performance is poor in Act88F>E2f1-RNAi adult flies, whereas in E2f2 mutant it is normal. Female flies were flipped into a mineral-coated column, and the frequency of flies landing over the height of the column was scored. Box plots (Min to Max), Mann–Whitney test, ***P<0.001. Three independent experiments were conducted. (c) n=147,205, (f) n=90,91 flies per genotype. (g,h) Muscle-specific gene expression is compromised in Act88F>E2f1-RNAi flight muscles of pharate, whereas no gross alteration is found in E2f2 mutant. Genes are how, fln, Lmpt, sals, Tm1, Mef2, Tm2, Mhc, Act88F, Mlc2 and salm. Mean±s.e.m., N=3 independent samples per genotype, two-way ANOVA, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. Genotypes (a–c,g) Act88F-GAL4;UAS-mCherry-RNAi and Act88F-GAL4;UAS-E2f1-RNAi, (d–f,h) E2f2c03344/+ and E2f2c03344/E2f276Q1. Pharate (P96 h APF, a,b,g) and adult flies (c,d–f,h).

Transverse sections of thoraces of Act88F>E2f1-RNAi pharates were co-stained with Phalloidin and β-PS integrin antibody to reveal the organization of the DLMs. The depletion of E2f1 resulted in the reduced overall size of DLMs, while the overall structure and the number of DLMs remained unaffected (Fig. 8a). The area of DLM4 cross-sections, as well as DLM3, was significantly reduced in Act88F>E2f1-RNAi (Fig. 8a), which was highly reminiscent of the muscle defect in Mef2>Dp-RNAi (Fig. 3d). Notably, the analysis of DLM sagittal sections revealed an altered myofibril assembly (Fig. 8b), like in Dp-depleted muscles (Fig. 5a–c). Importantly, Act88F>E2f1-RNAi adult flies were severely impaired in their ability to fly, implying dysfunctional flight muscles (Fig. 8c). In this test, adult flies with fully functional flight muscles were able to fly to the highest region of the 1,000-ml cylinder when flipped into the column, while flightless flies usually fall to the bottom of the cylinder19. The relative distribution of flies over the height of the cylinder and the median distribution are shown in Fig. 8c. In contrast, the loss of E2f2 had no effect on muscle size, myofibril width or the ability to fly (Fig. 8d–f).

To understand why the inactivation of E2f1 exerts a stronger effect on muscle morphology and function than the loss of E2f2, we evaluated the expression of myogenic genes in the flight muscles of each genotype. In agreement with the muscle defects observed above, the expression of myogenic genes was strongly deregulated in the absence of E2f1 (Fig. 8g). Depletion of E2f1 resulted in the downregulation of Tm2, Act88F and Mlc2 genes. Interestingly, we observed higher levels of the myogenic regulators Mef2, how and salm that regulate the expression of muscle genes. This may explain why some structural genes were expressed at normal or higher levels in E2f1 depletion. Unlike E2f1, the loss of E2f2 exerted a much weaker effect on the myogenic transcriptional programme (Fig. 8h). Although some of the muscle-specific genes were slightly downregulated in the flight muscles of the E2f2 mutant, none of the changes were statistically significant.

Collectively, these results suggest that E2f1 provides greater contribution to adult skeletal muscle development than E2f2.

Discussion

In this report, we addressed a long-standing question in the E2F field: why do E2F-deficient animals die? Our goal was to understand what is the essential function of E2F in animal development. By expressing a Dp transgene in a spatially restricted pattern in Dp null mutant animals, we identified adult skeletal muscles as a critical tissue in which E2F function is necessary and sufficient for animal viability. Surprisingly, E2F requirement was restricted to late myogenesis when muscles undergo extensive growth. E2F occupies the promoters of muscle-specific genes, and their expression is markedly reduced in the absence of E2F, suggesting that E2F is directly involved in the control of myofibrillogenesis (Fig. 9). Thus, the role of E2F in regulating skeletal muscle growth is essential for animal viability.

Figure 9. Model of myogenic gene expression regulation by E2F/Dp during Drosophila development.

The adult myoblasts are localized in the adepithelial layer of wing discs. The myoblasts proliferate through larval development and fuse to the nascent muscle fibres in the thoracic cavity of pupae. On completion of fusion (∼36 h APF), the developing DLMs significantly increase their size, and both sarcomere units and myofibrils are assembled. Although E2F/Dp complexes occupy promoters of myogenic genes throughout development, they are needed only within a narrow temporal window during muscle growth to directly control the expression of several muscle genes. This novel role for E2F in late muscle differentiation is necessary and sufficient for adult fly viability.

Previous genome-wide studies in Drosophila revealed two broad categories of E2F target genes6,7,8. One group is regulated primarily by E2f1 activation and consists of cell cycle genes. Another group comprises genes related to gametogenesis, development and differentiation. These targets are regulated exclusively by E2f2-dependent repression, while E2f1 is never present on these targets. Therefore, the role of Drosophila E2F in differentiation was thought to prevent the inappropriate expression of differentiation programmes in cycling cells. Here we show that E2f1 has an important function in late muscle differentiation, where it controls the expression of muscle-specific genes.

Even though both E2f1 and E2f2 can be detected using ChIP on myogenic genes at different developmental stages, E2f1 is more important than E2f2 during muscle growth. This conclusion is supported by the strong impact of E2f1 knockdown on the size of the indirect flight muscles, and the poor performance of E2f1-depleted muscles in the flight ability test. In contrast, the E2f2 mutation did not affect muscle size and function nor myogenic gene expression. These observations point to the functional importance of E2f1 during myogenic differentiation. However, we noted that Act88F>E2f1-RNAi results in a less severe phenotype than the knockdown of Dp with Mef2-GAL4. The differences in the severity of the phenotypes could be due to the knockdown efficiency of E2f1 and Dp, which is always a concern with any RNAi experiment, and the different strength, tissue specificity and timing of expression of two GAL4 drivers. Alternatively, this difference may reflect a partial redundancy between E2f1 and E2f2 since Dp depletion functionally inactivates both E2fs. In agreement, the knockdown of E2f1 exerted less severe effect on target gene expression in comparison with Dp depletion; thus, E2f2 could partially compensate for the loss of E2f1. Such an interpretation also parallels the relationship between the mammalian activator E2f3a and the repressor E2f4 during neuronal differentiation. In neural precursor cells (NPCs), both E2f3a and E2f4 bind and regulate the expression of differentiation genes; however, only E2f3 and not E2f4-deficient NPCs exhibit differentiation defects38,39.

The knockdown of Dp in the myogenic lineage revealed that the major defect associated with the loss of E2F function is the dramatic reduction in the size of the adult skeletal muscles. The most obvious explanation is that this is due to the reduced proliferation of Dp-deficient myoblasts, which would decrease the pool of myoblasts available for the formation of myotubes. A reduction in the number of myoblasts was shown to result in smaller muscles24,40,41. However, Dp-depleted myoblasts proliferated normally within the adepithelial layer in the wing imaginal disc, and there was no clear reduction in the number of migrating Dp-depleted myoblasts during fusion or in the number of nuclei in myotubes after the completion of fusion. The apparent lack of proliferation defect is in agreement with the normal packing density of myofibrils in Dp-depleted muscles, since reducing the number of myoblasts would result in loosely packed myofibrils24. In addition, altered myoblast proliferation was shown to reduce the total number of DLMs24,40,41, which was not the case in Dp-depleted muscles. Despite the lack of proliferation defects, we noted a small decrease in the number of nuclei in fully differentiated Dp-depleted fibres at 96 h APF, indicating that some nuclei are eliminated during muscle growth. However, the reduction in the number of nuclei does not precede the muscle growth defect, and therefore it is likely to be a secondary event. Thus, the knockdown of Dp does not interfere with the normal progression of development, and E2F function is dispensable for cell proliferation in flight muscle development.

During late myogenesis, muscle volume increases because of the continuous addition of filaments to myofibrils and accompanied muscle growth. These processes rely on high levels of expression of muscle-specific structural proteins. How the expression of late myogenic genes is maintained in adult muscles is not completely understood. The Cf2 transcription factor was previously linked to the control of structural gene expression; however, it acts as a repressor in adult flight muscles32. Other factors that may operate at this point to maintain muscle gene expression have not yet been identified, but might include Salm, Exd, Hth and the alternative splicing regulator Arrest, which are all involved in muscle fibre specification42,43,44,45. One implication of our work is that E2F contributes to the high level of expression of late muscle genes, and this contribution is needed to support myofibrillogenesis and muscle growth (Fig. 9). Among myogenic E2F targets are the muscle structural genes, including Act88F, Mhc and fln. Intriguingly, myofibrils were shown to be thinner in Act88F and Mhc heterozygotes, suggesting that even small changes in the levels of structural proteins, as found in Dp-depleted muscles, alter the stoichiometry of contractile proteins and could affect myofibril assembly46,47. Consistently, the sarcomere structure was less pronounced and the myofibril width was reduced in Dp-depleted muscles, indicating the presence of subtle defects in myofibril assembly. However, E2F is detected only on a subset of promoters of downregulated myogenic genes, suggesting that some of the transcriptional changes observed in Mef2>Dp-RNAi could be indirect. This could be the consequence of the altered expression of the key myogenic regulators, such as Mef2, how and Lmpt, which are misexpressed in Dp-depleted muscle and are direct targets of E2F.

The size of the indirect flight muscles also depends on mitochondrial fusion24. E2F/Dp was previously shown to regulate the expression of mitochondria-associated genes in Dp-mutant animals. Therefore, Dp-dependent mitochondrial morphology defects could also account for the muscle growth phenotype in Dp-deficient adult skeletal muscles.

An unexpected finding of our work is that the lethality of E2F-deficient animals is largely due to the requirement of E2F in adult skeletal muscles. Thus, during Drosophila development the essential function of E2F is not to control cell proliferation but rather to regulate terminal differentiation by engaging a myogenic transcriptional programme. Intriguingly, mammalian E2F factors were shown to regulate differentiation of various cell types by promoting tissue-specific transcriptional programmes. During myogenic differentiation, E2f3 is recruited to the promoters of muscle-specific genes and plays a critical role in their regulation48. In NPCs, E2f3 and E2f4 govern cell fate decisions and directly regulate the expression of differentiation genes38. Thus, the role of E2F in the regulation of tissue-specific transcriptional programmes is highly conserved, and the relevance of our findings extends beyond the fly model.

Methods

Fly stocks

The lines 1151-GAL4 (refs 15, 16, 17), Act88F-GAL4 (ref. 17) and P{twi-βgal} were provided by Richard. M. Cripps. The stock P{PTT-un1}slsZCL2144 characterized as a Z-band marker in the indirect flight muscles49 expresses a GFP-tagged Sls protein50. The line weeP26 produces a Mhc-IFM19 splice variant fused to GFP51. The stock vgAME-lacZ was used to mark the developing indirect flight muscles26. The stock P{PTT-GA}DpCA06954 (ref. 22) from the Carnegie collection, here annotated as DpGFP, contains a GFP-expressing protein trap insertion. The expression of the GFP::Dp fusion protein was confirmed using western blot analysis (see details in Supplementary Fig. 2B). The P{UAS-Dp.D} stock used to overexpress Dp was recombined out from P{UAS-E2f1.N}3B,P{UAS-Dp.D}1-4b/TM6B,Tb (refs 52, 53). The Dp−/− null mutant, denoted here as Dpa3/Df(2R)Exel7124, is a trans-heterozygote between the Dpa3 null allele of Dp (refs 5, 10) and the deficiency Df(2R)Exel7124, which deletes the entire Dp gene. The stocks P{UAS-mito-HA-GFP.AP}, which expresses GFP with a mitochondrial import signal, P{UAS-GFP.nls}, which expresses GFP with a nuclear localization signal, the GAL4 drivers P{GawB}how24B, P{GAL4-Mef2.R}54, P{Mhc-GAL4.F3-580}32, P{GAL4-twi.G}, P{GAL4-twi.2xPE}, P{GAL4-arm.S}, P{GawB}AB1, P{GawB}c729, P{GawB}34B, P{r4-GAL4}, P{GawB}elavC155, P{nSyb-GAL4.P}, P{GawB}D42, P{GawB}inscMz1407, P{GawB}tey5053A and Act5C-GAL4, were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA). The line rP298-GAL4 (ref. 55), a GAL4 insertion in the kirre locus (also known as Duf) was a gift from Mary K Baylies. The stocks P{tinC-Gal4.Δ4} and P{bap3-GAL4} were kindly provided by Manfred Frasch56,57. Both P{Hand4.2-GAL4} and P{GMH5-GAL4}58 stocks were a gift from Rolf Bodmer. The line UAS-Dp-RNAi was obtained from the library RNAi-GD (ID 12722) at the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (Vienna, Austria). The gene expression phenotype was confirmed using P{TRiP.JF02519}attP2 from TRiP at Harvard Medical School. The lethality phenotype using Mef2-GAL4 driver was confirmed with UAS-Dp-RNAi4654R-2 from NIG-Fly Stock centre and P{TRiP.HMS00245}attP2 from TRiP. The lines {UAS-E2f1-RNAi}37, E2f2c03344 and E2f276Q1 (refs 9, 59) were used. The stocks P{VALIUM20-mCherry}attP2 and P{UAS-mCherry.VALIUM10}attP2 from TRiP collection were used as control and obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. All fly crosses were made at 25 °C in vials containing standard cornmeal-agar medium, except for the crosses containing Act88F-GAL4 driver, which were kept at 29 °C during development.

Fly viability experiment

Fly viability was assessed by collecting and transferring third instar larvae to fresh vials at 25 °C. The total number of larva, pupa, as well as pharate pupa, and adult flies able to eclose out of the pupal case was scored over time. The pupal developmental stages were assessed by following markers of metamorphosis as described in ref. 60. Images of 2- to 5-day-old adult flies were taken with the microscope Zeiss Discovery V8, × 0.63. In the case of the rescue experiments, at least 65 flies per genotype were scored in three independent experiments, except for the rescue using 1151-GAL4 driver, which was performed twice. The genotypes were confirmed using PCR and sequencing in the rescue experiments using Mef2-GAL4 and 1151-GAL4 drivers in the Dp-mutant background. The viability experiment using different GAL4 drivers and Dp-RNAi was scored at least twice if Dp knockdown induced lethality.

Flight test

The test of flight ability was adapted from ref. 19. Adult females were collected on eclosion and recovered at 25 °C for 4–6 days. A 1,000-ml cylinder was coated with mineral oil. Flies were flipped to the top of the column. Flies able to fly land on the top section of the column, while flightless flies fall to the bottom of the cylinder. The landing spot along the height of the cylinder was scored for each fly, and the frequency of landing spots per height of the cylinder was plotted. Each experiment was carried out three times. At least 20 flies per genotype were tested in each replicate.

Histology

Pharate animals were removed from their pupal case at 96 h APF and were fixed with 4% formaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Thoraces were embedded in paraffin, and sections of 8-μm thickness were cut using a microtome61. Haemotoxylin and eosin staining was performed using standard procedures. Images were taken using the bright-field microscope Zeiss ApoTome. At least 16 flies per genotype were scored.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Tissues were dissected and immediately fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS twice for 10 min each and blocked in 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min. Samples were incubated with antibodies overnight at 4 °C in 2% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. After washing four times for 10 min each in 0.1% Triton X-100 (in PBS), samples were incubated with appropriate Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, used at 1:300) for 90 min in 10% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. After washing with 0.1% Triton X-100 (in PBS), tissues were stored in glycerol with antifade, and then mounted on glass slides. All steps were performed at room temperature, unless otherwise stated. The DLMs of pupa staged at 21 h APF were dissected as in ref. 62, fixed for 20–30 min, and washed in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100. Thoraces of 2- to 5-day-old adult or pharate pupa staged at ∼96 h APF were fixed for 30 min in relaxing buffer. Thoraces were bisected in the sagittal plane, and were then fixed for an additional 15 min as described in ref. 63. In the case of transverse plane sectioning, flies were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and cut twice with a razor. The transverse sections were fixed for 1 h (ref. 24). For larval body wall musculature staining, larva was dorsally opened, pinned in a Sylgard dish and fixed for 20 min. A minimum of five to eight animals per genotype was dissected per experiment, except for the experiment that required quantitative analysis, in which case the staining was carried out two or three times.

The primary antibodies were mouse anti-β-gal (40-1a, 1:200, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)), mouse anti-β PS-integrin (CF.6G11, 1:50, DSHB), rabbit polyclonal anti-Dp (#212, 1:300)7 and rabbit anti-Mef2 (1:1,000)64. Rhodamine–phalloidin or fluorescein isothiocyanate–phalloidin were used to counterstain and stain thin filaments, and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for nucleus staining.

Fluorescent images were acquired with the laser-scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM Observer.Z1) using × 20/0.8, × 40/1.2 and × 100/1.45 objectives. Images were processed using Photoshop (Adobe Systems). All images are confocal single-plane images and are oriented anterior to the left, unless otherwise stated. Only representative images are shown.

Quantitative and statistical analysis

The total number of myoblasts in the adepithelial cells of the wing disc in late third instar larvae (120 h after egg-laying) was determined by marking the adult myoblast with twi-lacZ and Mef2 antibodies. Images were taken with confocal microscopy in a z-stack to cover all nuclei in the adepithelial layer, and then were projected into a single plane. The area covered by the adult myoblasts, as well as the disc area, was quantified using the ImageJ software. The plugin Image-based Tool for Counting Nuclei was used to determine the myonuclear number in the myoblast-positive area of the adepithelial layer. A minimum of 10 wing discs per genotype was scored.

The density and size of nuclei at 21 and 40 h APF were determined by staining nuclei of both myoblasts and developing DLMs using Mef2 antibody. Both the number and area of nuclei were measured using the analyse particle tool of the ImageJ software. The area of the selected region of interest was measured to calculate nuclear density. Two or three independent experiments were conducted per time point. A minimum of eight animals per genotype was scored.

The number of myofibrils was counted as the number of peaks of grey value (that is, Phalloidin intensity) over a distance of 20 or 40 μm using the plot profile tool from the ImageJ software. Three independent lines perpendicular to myofibril orientation were drawn over a set of myofibril clusters to count the number of peaks (that is, myofibrils). An average was calculated for each image (that is, hemithorax). Myofibril width was calculated as the distance divided by the total number of myofibrils within the selected region. At least six hemithoraces per genotype was quantified.

ImageJ was also used to quantify DLM 3 and DLM 4 cross-section area, as well as the myofibril cluster area in the transverse sections of indirect flight muscles, and the total area of the body wall muscle VL3. The numbers of muscle fibres, myofibrils and nuclei were manually counted per DLM cross-section in pharate animals. At least two independent experiments were conducted. A minimum of eight flies per genotype was quantified.

Images of the DLM sagittal section were blindly scored as either tubular or thin/fragmented regarding mitochondrial shape. At least 15 hemithoraces stained with mitoGFP were quantified per genotype. Two independent experiments were conducted.

Graphs were generated with the GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (Graphpad Software). The group means were analysed for overall statistical significance using the unpaired Student's t-test with Welch's correction, two-way analysis of variance and non-parametric analysis (Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis).

RT–qPCR and ChIP–qPCR

Tissue was dissected as described above from at least three to five different animals. Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription to measure standard mRNAs was performed using the SensiFAST cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bioline) according to the manufacturer's specifications. qPCR was performed with the SensiFast SYBR No-ROX Mix (Bioline) on a LightCycler 480 (Roche). The reference genes RpL32, RpL30 and β-tubulin were validated as stable control genes65. Normalization was calculated using the geometric mean of these reference genes. Primer sequences are in Supplementary Table 2. At least three independent biological samples were collected for each genotype and developmental stage. Each sample was measured twice. Raw data for ChIP–qPCR presented in Fig. 7a are in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, and raw data included in Fig. 7b are in Supplementary Table 5.

The degenerate E2F-binding sites NWTSSCSS7 and the Drosophila E2F motif TTGGCGC6 were identified from searches carried out with the Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools66. The evolutionary conservation between D. melanogaster and D. erecta was considered to predict E2F-binding sites.

At least 15 animals staged at third instar larvae, and pupae at∼24 and 96 h APF were dissected out of their pupal cases and homogenized. Chromatin was extracted using homogenizer with 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM sodium butyrate and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche) as in ref. 67. Samples were crosslinked for 15 min at room temperature in 1.8% formaldehyde, and 225 mM Glycine was added. Then, cells were lysed with 15 mM HEPES at pH 7.6, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% lauroylsarcosine and 10 mM sodium butyrate with protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche), and were sheared using a Branson 450 Sonifier. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-DP (#212 (ref. 7)), mouse anti-Rbf (DX3/DX5, ratio 1:1 (ref. 68)), rabbit anti-E2f1 (#210 (refs 7, 69), ratio 1:1) and rabbit anti-E2f2 antibodies (#79 (9)). Rabbit IgG (Sigma) was used as nonspecific antibodies. Complexes were pulled down with Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen), washed with lysis buffer four times, washed twice with TE (pH 8), eluted and decrosslinked overnight at 65 °C; RNA was degraded with RNase A (Sigma) for 1 h at 37 °C and protein was digested with proteinase K for 2 h at 50 °C. DNA was purified by phenol–chloroform extraction, followed by overnight ethanol precipitation. The input genomic DNA (before precipitation), as well as immunoprecipitated DNA, was quantified using qPCR as described here. Primer sequences are in Supplementary Table 2. A negative sequence site that does not contain any predicted E2F-binding sites, and the positive target genes, Arp53D, was used as controls (Supplementary Table 2). The protein enrichment was calculated as the percentage of immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input DNA (prior DNA precipitation) for each antibody. Data presented are relative to the negative binding site for each ChIP. Each sample was measured twice.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zappia, M. P. and Frolov, M. V. E2F function in muscle growth is necessary and sufficient for viability in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 7:10509 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10509 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-4 and Supplementary Tables 1-5

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Cripps, N. Dyson, F. Schnorrer, M. Spletter and M. Truscott for helpful discussions. We are grateful to M.K. Baylies, M. Frasch, A. Lalouette, R.M. Cripps, F. Demontis, M.V. Taylor, E.E.M. Furlong, the Bloomington Stock Center, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, the TRiP at Harvard Medical School and the NIG-Fly Stock Center for fly stocks, and to B. Paterson and the DSHB for antibodies. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant GM93827 and GM110018 (M.V.F.), by a Scholar Award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (M.V.F.) and by the postdoctoral fellowship from American Heart Association (M.P.Z.).

Footnotes

Author contributions M.P.Z. and M.V.F. conceived the project, designed the experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. M.P.Z. performed the experiments.

References

- DeGregori J. & Johnson D. G. Distinct and overlapping roles for E2F family members in transcription, proliferation and apoptosis. Curr. Mol. Med. 6, 739–748 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaquinta P. J. & Lees J. A. Life and death decisions by the E2F transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 649–657 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.-Z., Tsai S.-Y. & Leone G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 785–797 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Heuvel S. & Dyson N. J. Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 713–724 (2008) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolov M. V., Moon N.-S. & Dyson N. J. dDP is needed for normal cell proliferation. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 3027–3039 (2005) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenjak M., Anderssen E., Ramaswamy S., Whetstine J. R. & Dyson N. J. RBF binding to both canonical E2F targets and noncanonical targets depends on functional dE2F/dDP complexes. Mol. Cell Biol. 32, 4375–4387 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova D. K., Stevaux O., Frolov M. V. & Dyson N. J. Cell cycle-dependent and cell cycle-independent control of transcription by the Drosophila E2F/RB pathway. Genes Dev. 17, 2308–2320 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georlette D. et al. Genomic profiling and expression studies reveal both positive and negative activities for the Drosophila Myb MuvB/dREAM complex in proliferating cells. Genes Dev. 21, 2880–2896 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolov M. V. et al. Functional antagonism between E2F family members. Genes Dev. 15, 2146–2160 (2001) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royzman I., Whittaker A. J. & Orr-Weaver T. L. Mutations in Drosophila DP and E2F distinguish G1-S progression from an associated transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 11, 1999–2011 (1997) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D. & VijayRaghavan K. in Muscle Development in Drosophila (ed. Sink H. 125–138Landes Bioscience/Springer Science (2006) . [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J., Bate M. & Vijayraghavan K. Development of the indirect flight muscles of Drosophila. Development 113, 67–77 (1991) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate M., Rushton E. & Currie D. A. Cells with persistent twist expression are the embryonic precursors of adult muscles in Drosophila. Development 113, 79–89 (1991) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganayakulu G. et al. A series of mutations in the D-MEF2 transcription factor reveal multiple functions in larval and adult myogenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 171, 169–181 (1995) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S. & VijayRaghavan K. Homeotic genes and the regulation of myoblast migration, fusion, and fibre-specific gene expression during adult myogenesis in Drosophila. Development 124, 3333–3341 (1997) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anant S., Roy S. & VijayRaghavan K. Twist and Notch negatively regulate adult muscle differentiation in Drosophila. Development 125, 1361–1369 (1998) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryantsev A. L., Baker P. W., Lovato T. L., Jaramillo M. S. & Cripps R. M. Differential requirements for Myocyte Enhancer Factor-2 during adult myogenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 361, 191–207 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler C., Daczewska M., Da Ponte J. P., Dastugue B. & Jagla K. Coordinated development of muscles and tendons of the Drosophila leg. Development 131, 6041–6051 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps R. M., Ball E., Stark M., Lawn A. & Sparrow J. C. Recovery of dominant, autosomal flightless mutants of Drosophila melanogaster and identification of a new gene required for normal muscle structure and function. Genetics 137, 151–164 (1994) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myster D. L., Bonnette P. C. & Duronio R. J. A role for the DP subunit of the E2F transcription factor in axis determination during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 127, 3249–3261 (2000) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royzman I., Austin R. J., Bosco G., Bell S. P. & Orr-Weaver T. L. ORC localization in Drosophila follicle cells and the effects of mutations in dE2F and dDp. Genes Dev. 13, 827–840 (1999) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M. et al. The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics 175, 1505–1531 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D., Anant S., Ruiz-Gomez M., Bate M. & VijayRaghavan K. Founder myoblasts and fibre number during adult myogenesis in Drosophila. Development 131, 3761–3772 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai M. & Nongthomba U. Effect of myonuclear number and mitochondrial fusion on Drosophila indirect flight muscle organization and size. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 2566–2577 (2013) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. C. & Beall C. Ultrastucture of developing flight muscle in drosophila. assembly of myofibrils. Dev. Biol. 160, 443–465 (1993) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard F. et al. Integration of differentiation signals during indirect flight muscle formation by a novel enhancer of Drosophila vestigial gene. Dev. Biol. 332, 258–272 (2009) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigoreaux J. O., Saide J. D., Valgeirsdottir K. & Pardue M. Lou. Flightin, a novel myofibrillay protein of Drosophila stretch activated muscles. J. Cell Biol. 121, 587–598 (1993) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg E. A., Mahaffey J. W., Bond B. J. & Davidson N. Transcripts of the six Drosophila actin genes accumulate in a stage- and tissue-specific manner. Cell 33, 115–123 (1983) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz R. et al. Expression patterns of the whole Troponin C gene repertoire during Drosophila development. Gene Expr. Patterns 4, 183–190 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfanos Z. & Sparrow J. C. Myosin isoform switching during assembly of the Drosophila flight muscle thick filament lattice. J. Cell Sci. 126, 139–148 (2013) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigoreaux J. O. Genetics of the Drosophila flight muscle myofibril: a window into the biology of complex systems. Bioessays 23, 1047–1063 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski K. M. & Schulz R. A. CF2 represses Actin 88F gene expression and maintains filament balance during indirect flight muscle development in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 5, e10713 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai M., Katti P. & Nongthomba U. Drosophila Erect wing (Ewg) controls mitochondrial fusion during muscle growth and maintenance by regulation of the Opa1-like gene. J. Cell Sci. 127, 191–203 (2014) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus A. M. et al. Loss of dE2F compromises mitochondrial function. Dev. Cell 27, 438–451 (2013) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook A., Xie J., Du W. & Dyson N. Requirements for dE2F function in proliferating cells and in post-mitotic differentiating cells. EMBO J. 15, 3676–3683 (1996) . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duronio R. J., O'Farrell P. H., Xie J.-E., Brook A. & Dyson N. The transcription factor E2F is required for S phase during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 9, 1445–1455 (1995) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris E. J. et al. E2F1 represses beta-catenin transcription and is antagonized by both pRB and CDK8. Nature 455, 552–556 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian L. M. et al. Tissue-specific targeting of cell fate regulatory genes by E2f factors. Cell Death Differ http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2015.36 (2015) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan K. a. et al. Unique requirement for Rb/E2F3 in neuronal migration: evidence for cell cycle-independent functions. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4825–4843 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D. & Kumar Roy J. Rab11 plays an indispensable role in the differentiation and development of the indirect flight muscles in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 8, e73305 (2013) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J. J. et al. A dominant negative form of Rac1 affects myogenesis of adult thoracic muscles in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 285, 11–27 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbauer C. et al. Spalt mediates an evolutionarily conserved switch to fibrillar muscle fate in insects. Nature 479, 406–409 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryantsev A. L. et al. Extradenticle and homothorax control adult muscle fiber identity in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 23, 664–673 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oas S. T., Bryantsev A. L. & Cripps R. M. Arrest is a regulator of fiber-specific alternative splicing in the indirect flight muscles of Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 206, 895–908 (2014) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spletter M. L. et al. The RNA-binding protein Arrest (Bruno) regulates alternative splicing to enable myofibril maturation in Drosophila flight muscle. EMBO Rep. 16, 178–192 (2015) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall C. J., Sepanski M. A. & Fyrberg E. A. Genetic dissection of Drosophila myofibril formation: effects of actin and myosin heavy chain null alleles. Genes Dev. 3, 131–140 (1989) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Zaragoza E., Mas J. A., Vivar J., Arredondo J. J. & Cervera M. CF2 activity and enhancer integration are required for proper muscle gene expression in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 125, 617–630 (2008) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asp P., Acosta-Alvear D., Tsikitis M., Van Oevelen C. & Dynlacht B. D. E2f3b plays an essential role in myogenic differentiation through isoform-specific gene regulation. Genes Dev. 23, 37–53 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart C. et al. Modular proteins from the Drosophila sallimus (sls) gene and their expression in muscles with different extensibility. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 953–969 (2007) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin X., Daneman R., Zavortink M. & Chia W. A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15050–15055 (2001) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne P. J., Brotman J. S., Sweeney S. T. & Davis G. Green fluorescent protein tagging Drosophila proteins at their native genomic loci with small P elements. Genetics 165, 1433–1441 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Xie J.-E. & Dyson N. J. Ectopic expression of dE2F and dDP induces cell proliferation and death in the Drosophila eye. EMBO J. 15, 3684–3692 (1996) . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld T. P., de la Cruz A. F. A., Johnston L. A. & Edgar B. A. Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell 93, 1183–1193 (1998) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganayakulu G., Schulz R. a. & Olson E. N. Wingless signaling induces nautilus expression in the ventral mesoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 176, 143–148 (1996) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon S. D. & Chia W. Drosophila Rolling pebbles: a multidomain protein required for myoblast fusion that recruits D-Titin in response to the myoblast attractant dumbfounded. Dev. Cell 1, 691–703 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo P. C. H. & Frasch M. A role for the COUP-TF-related gene seven-up in the diversication of cardioblast identities in the dorsal vessel of Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 104, 49–60 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffran S., Küchler A., Lee H. H. & Frasch M. biniou (FoxF), a central component in a regulatory network controlling visceral mesoderm development and midgut morphogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 15, 2900–2915 (2001) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells R. J., Fitzgerald E., Cypser J. R., Tatar M. & Bodmer R. Insulin regulation of heart function in aging fruit flies. Nat. Genet. 36, 1275–1281 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus A. M., Nicolay B. N., Rasheva V. I., Suckling R. J. & Frolov M. V. dE2F2-independent rescue of proliferation in cells lacking an activator dE2F1. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 8561–8570 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Golic K. G. & Hawley R. S. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press (2005) . [Google Scholar]

- Morriss G. R. et al. in Myogenesis Vol. 798, ed. DiMario J. X. 127–152Humana Press (2012) . [Google Scholar]

- Weitkunat M. & Schnorrer F. A guide to study Drosophila muscle biology. Methods 68, 2–14 (2014) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F. et al. Systematic genetic analysis of muscle morphogenesis and function in Drosophila. Nature 464, 287–291 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly B. et al. Requirement of MADS domain transcription factor D-MEF2 for muscle formation in Drosophila. Science 267, 688–693 (1995) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J. et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3, RESEARCH0034 (2002) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden J. Regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3593–3596 (2003) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre N., Lavrov S., Hennetin J., Bellis M. & Cavalli G. Mapping the distribution of chromatin proteins by ChIP on chip. Methods Enzymol. 410, 316–341 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W. E. I., Vidal M., Xie J.-E. & Dyson N. RBF, a nove RB-related gene that regulates E2F activvity and interacts with cyclin E in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 10, 1206–1218 (1996) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seum C. et al. Position-effect variegation in Drosophila depends on dose of the gene encoding the E2F transcriptional activator and cell cycle regulator. Development 122, 1949–1956 (1996) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-4 and Supplementary Tables 1-5