Abstract

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) profoundly suppress estrogen levels in postmenopausal women and are effective in breast cancer prevention among high-risk postmenopausal women. Unfortunately, AI treatment is associated with undesirable side effects that limit patient acceptance for primary prevention of breast cancer. A double-blind, randomized trial was conducted to determine whether low and intermittent doses of letrozole can achieve effective estrogen suppression with a more favorable side effect profile. Overall, 112 postmenopausal women at increased risk for breast cancer were randomized to receive letrozole at 2.5 mg once daily (QD, standard dose arm), 2.5 mg every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (Q-MWF), 1.0 mg Q-MWF or 0.25 mg Q-MWF for 24 weeks. Primary endpoint was suppression in serum estradiol levels at the end of letrozole intervention. Secondary endpoints included changes in serum estrone, testosterone, C-telopeptide (marker of bone resorption), lipid profile and quality of life measures (QoL) following treatment. Significant estrogen suppression was observed in all dose arms with an average of 75 – 78% and 86 – 93% reduction in serum estradiol and estrone levels, respectively. There were no differences among dose arms with respect to changes in C-telopeptide levels, lipid profile, adverse events (AEs) or QoL measures. We conclude that low and intermittent doses of letrozole are not inferior to standard dose in estrogen suppression and resulted in a similar side effect profile compared to standard dose. Further studies are needed to determine the feasibility of selecting an effective AI dosing schedule with better tolerability.

Keywords: letrozole, dosing regimens, breast cancer risk, estrogen suppression

Introduction

Prospective studies indicate a positive relationship between circulating estrogen levels in postmenopausal women and breast cancer risk [1]. The main source of estrogen in postmenopausal women arises from the conversion of androgens to estrogens by aromatase within adipose tissue. Adjuvant trials have shown that aromatase inhibitors (AI) (letrozole, exemestane, anastrozole) are more effective than tamoxifen in preventing breast cancer recurrence and reducing the risk of contralateral tumors in postmenopausal women [2, 3]. Exemestane and anastrozole are effective in breast cancer prevention among high-risk postmenopausal women as shown in two randomized, placebo-controlled trials [4, 5]. Unfortunately, AI therapy is associated with significant adverse events (AEs) which limit patient acceptability [6, 7]. There has been great interest in finding the lowest, effective AI dose that can improve drug tolerability and lead to better drug uptake and adherence.

Letrozole is the most potent nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor with respect to tissue and plasma estrogen suppression in postmenopausal women [8–10]. The current therapeutic dose of letrozole is 2.5 mg once daily for the treatment of hormone sensitive breast cancer in both the adjuvant and metastatic settings. Early phase clinical trials have explored the endocrine and clinical activity of lower letrozole doses in postmenopausal women with advanced hormone sensitive breast cancer. Daily letrozole doses ranging from 0.1 – 1.0 mg reduced serum estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2) levels to greater than 86% and 67% within two weeks of treatment, respectively [11–13]. In another study, daily letrozole doses of 0.5 mg reduced E1 and E2 levels below the limit of detection in 73% and 24% of patients, respectively [14]. In this study, no differences were observed in the AE profiles between the 0.5 mg and 2.5 mg daily dosing groups [14]. The half-life for letrozole is 3–4 days [15] suggesting that daily dosing may lead to increased drug accumulation and toxicity and that non-daily dosing may effectively suppress estrogen. Earlier studies have shown that serum estrogen suppression of greater than 72 hours was maintained with a single dose of 0.1 or 0.5 mg letrozole; and estrogen suppression was maintained for 7 days with a single 2.5 mg dose [16]. Taken collectively, the data suggest that low and intermittent letrozole doses may provide adequate estrogen suppression for chemoprevention.

We conducted a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding study of letrozole to determine whether low and intermittent doses can achieve effective estrogen suppression with a more favorable side effect profile than standard dosing in postmenopausal women with increased breast cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was a double-blind, randomized study conducted at the University of Arizona Cancer Center and Mayo Clinic Rochester to evaluate alternative letrozole dosing regimens. The primary study endpoint was the percentage of serum E2 suppression following 24 weeks of letrozole intervention. The secondary endpoints included the effects of letrozole intervention on serum E1 and testosterone levels, C-telopeptide (biochemical marker of bone resorption), lipid profile, AEs and quality of life (QoL) measures. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution.

Study Drug

Study drug was supplied by the Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute. The drug product was distributed as a hard, gelatin capsule (size 3) for oral administration. Each capsule contained 0 (placebo), 0.25, 1.0 or 2.5 mg of USP grade letrozole as the active ingredient. Inactive components included microcrystalline cellulose, lactose monohydrate, crospovidone, colloidal silicon dioxide, and magnesium stearate. The content of microcrystalline cellulose was adjusted to compensate for the different masses of letrozole drug substance in the different strength capsules, while the content of the remaining ingredients remained constant. Capsules were packaged in blister cards to facilitate drug adherence with intermittent dosing schedule. For the 2.5 mg QD arm, each blister contained a capsule with 2.5 mg of letrozole. For the intermittent dosing arms, blisters corresponding to Monday, Wednesday, and Friday contained capsules with the respective amount of letrozole (2.5 mg, 1.0 mg, or 0.25 mg) with placebo capsules packed in the remaining blisters.

Study Population

We recruited healthy postmenopausal women with ≥ 1.66% probability of developing invasive breast cancer within 5 years using the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/) or with a history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) treated by local excision alone. Postmenopausal status was defined as amenorrhea for greater than 12 months; history of hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; age ≥55 years of age with prior hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy; age 35 to 54 with a prior hysterectomy without oophorectomy or with unknown ovarian functional status with documented follicle-stimulating hormone level within the institution’s postmenopausal range. Other inclusion criteria included good performance status, normal liver and renal function, and a bilateral mammogram within the past year with a BIRADS score <3. Study exclusion criteria included a prior history of invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ; prior radiation therapy to the chest wall or breast; invasive cancer within the past five years except for non-melanoma skin cancer; concomitant treatment (or treatment within three months of study enrollment) with hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptives, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogs, prolactin inhibitors, anti-androgens, selective estrogen receptor modulators or herbal remedies; untreated osteoporosis; evidence of a suspicious lesion on bilateral mammogram within the past year requiring further workup. Written informed consent was obtained prior to study enrollment.

Study Procedures

Participants underwent clinical and laboratory evaluation for eligibility during the enrollment period. Eligible participants were randomized to receive 2.5 mg letrozole once daily (QD, standard dose arm), 2.5 mg letrozole every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (Q-MWF), 1.0 mg letrozole Q-MWF, or 0.25 mg letrozole Q-MWF for a 24-week period. Fasting morning blood samples were collected at baseline, end of letrozole treatment and 6-weeks post-intervention to obtain measurements of research endpoints and for safety monitoring. Adherence was determined by pill count and patient self-reporting during each visit. Safety of letrozole intervention was assessed by reported AEs and clinical labs. Adverse events were graded using NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. QoL was assessed using the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MENQOL) [17] and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) version 2 for health-related QoL [18].

Serum estrogen and testosterone levels were measured by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) assays [19, 20] with minor modifications to improve assay specificity. The detection limits were 1.25 pg/ml for E2, 0.63 pg/ml for E1 levels and 0.02 ng/ml for testosterone using 0.5 ml of serum. Samples with detection response below the limit of detection were assigned an arbitrary value. C-telopeptide levels were measured using an ELISA based immunoassay (Immunodiagnostic Systems, Inc. Fountain Hills, AZ). Lipid levels were determined in a certified commercial lab.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was the percentage of serum E2 suppression following 24 weeks of letrozole intervention. For study participants with missing serum E2 measurements at week 24 due to early termination of agent intervention, the serum E2 levels determined in the early termination samples were used to determine the suppression level at the end of intervention. Three one-sided two-sample t–tests were conducted on the ratio of the mean percentage of suppression of each of the three alternative dosing arms to that of the standard dose arm simultaneously to test for non-inferiority, where a non-inferiority margin of 0.7 was chosen. The same non-inferiority test was applied to compare the E1 suppression at the end of intervention in the alternative dosing arms to that in the standard dose arm. One-way ANOVA was performed to compare the continuous demographic characteristics (i.e. age and BMI) and mean percent change in serum C-telopeptide and cholesterol levels at the end of letrozole intervention among the dose groups. Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the categorical demographic characteristics among the dose groups.

Based on prior studies assessing the effects of AIs on quality of life, score changes of 5 points from baseline on SF-36 and 0.5 points from baseline on MENQOL were considered as potentially clinically meaningful [21, 22]. Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the proportion of women having worsened (SF-36 score, ≥5-point decrease; MENQOL score, ≥0.5-point increase), improved (SF-36 score, ≥5-point increase; MENQOL, ≥0.5-point decrease) or stable QoL relative to baseline among treatment groups. Fisher’s exact test was also performed to compare frequencies of self-reported AEs among the treatment groups.

Results

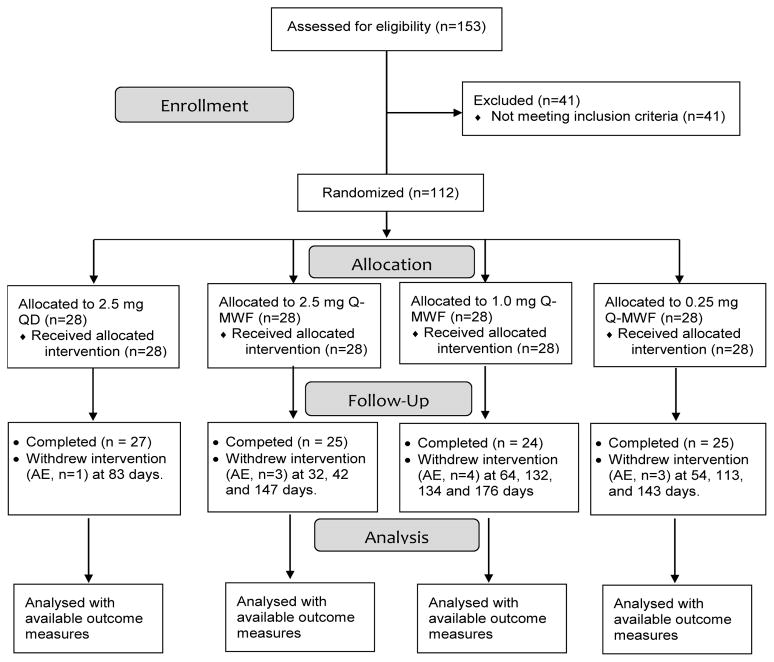

The study opened in March 2010 and closed to accrual in November 2013. The CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1. One hundred and twelve eligible participants were randomized into one of the four study arms (28 per arm). One, three, four, and three participants in the 2.5 mg QD, 2.5 mg Q-MWF, 1.0 mg Q-MWF, and 0.25 mg Q-MWF arm, respectively, were taken off agent intervention early due to AEs. Safety data were analyzed on all subjects who initiated agent intervention. Other endpoints were analyzed on all with available outcome data. The demographic characteristics and 5-year breast cancer risk of randomized participants are summarized in Table 1. These characteristics were well balanced among the dose arms. The mean age of participants was 63 years of age. Average BMI of participants was 29.8 ± 6.9 kg/m2. The majority of participants were white, non-Latino. The average 5-year breast cancer risk was 3.25 ± 1.54%. Sixty-two percent of study participants were accrued from the University of Arizona and 38% from Mayo Clinic in Rochester. The proportion of participants accrued between the 2 sites did not differ among treatment arms (p = 0.90). On average, participants took 98% of the assigned pills and there was no difference in agent adherence among the treatment arms (p = 0.63).

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT Diagram

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Variable | All (N=112) | 2.5 mg QD (N=28) | 2.5 mg Q-MWF (N=28) | 1.0 mg Q-MWF (N=28) | 0.25 mg Q-MWF (N=28) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 63±8a | 61±8 | 64±7 | 63±8 | 63±8 | 0.65 |

| White, n (%) | 110 (98.2%) | 28 (100%) | 27 (96.4%) | 28 (100%) | 27 (96.4%) | 1.00 |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 10 (8.9%) | 1 (3.6%) | 4 (14.3%) | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (10.7%) | 0.69 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.8±6.9 | 29.2±6.6 | 29.9±6.5 | 28.8±6.3 | 31.3±7.9 | 0.55 |

| 5-year breast cancer risk (%) | 3.25 ± 1.54 | 3.50 ± 2.01 | 3.08 ± 1.40 | 3.46 ± 1.40 | 2.97 ± 1.24 | 0.48 |

mean±standard deviation

derived from one-way ANOVA

Baseline serum estrogen levels and the percentage of estrogen suppression at the end of letrozole intervention are summarized in Table 2. Two participants in the 1.0 mg Q-MWF arm had elevated baseline serum E2 levels, resulting in a higher mean E2 level in this treatment arm. The percentage of estrogen suppression was significant for each dose arm (p < 0.0001) at the end of intervention with an average of 75 – 78% and 86 – 93% suppression for serum E2 and E1 levels, respectively. The percentage of estrogen suppression in the low and intermittent dose arms were non-inferior to standard dose arm at the end of letrozole intervention. Six weeks after letrozole discontinuation, the percentage of E2 suppression remained significant for the 2.5 mg QD (−29.0 ± 40.0%, p < 0.001) and 2.5 mg Q-WMF treatment arms (−33.2 ± 32.9%, p < 0.0001); the percentage of E1 suppression remained significant for each treatment arm (−39.5 ± 29.5% for 2.5 mg QD, p < 0.0001; −25.4 ± 31.9% for 2.5 mg Q-MWF, p < 0.01; −20.1 ± 35.5% for 1.0 mg Q-MWF, p = 0.01; −22.3 ± 34.4% for 0.25 mg Q-MWF, p < 0.01). Letrozole intervention did not result in significant changes in serum testosterone levels and there was no difference in the percent change of testosterone levels among the dose arms (data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline serum estrogen levels and percent change in serum estrogens at the end of letrozole intervention.

| Baseline | % Change | p-valuec | Upper CId | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol (E2), pg/ml | ||||

| 2.5 mg QD | 5.4±2.8a | −76.8±39.4 | <0.0001 | - |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 6.6±6.0 | −74.7±37.3 | <0.0001 | −62.7 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 16.9±42.6 | −77.7±33.6 | <0.0001 | −66.6 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 6.1±6.1 | −75.1±37.3 | <0.0001 | −63.0 |

| p-valueb | 0.16 | 0.99 | ||

| Estrone (E1), pg/ml | ||||

| 2.5 mg QD | 18.9±11.3 | −93.0±11.9 | <0.0001 | - |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 20.2±13.5 | −86.5±22.7 | <0.0001 | −79.1 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 18.1±13.7 | −88.1±20.6 | <0.0001 | −81.3 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 20.8±11.9 | −88.1±24.7 | <0.0001 | −80.1 |

| p-valueb | 0.85 | 0.66 |

mean±standard deviation

derived from one-way ANOVA

derived from paired t test for % changes within each group

upper bound of the one-sided 95% CI for % changes. All alternative dosing arms were non-inferior to the standard dose arm, based on a non-inferior margin of 0.7 (i.e., the upper bound in each alternative dosing arm was lower than 0.7 x mean % change in the standard dose arm)

Table 3 summarizes the change in serum C-telopeptide and lipids at the end of letrozole intervention. There were no differences in baseline C-telopeptide levels among the study arms. C-telopeptide levels increased significantly for each treatment group (47.67 ± 70.86% for 2.5 mg QD, p < 0.01, 37.08 ± 57.41% for 2.5 mg Q-MWF, p < 0.01; 48.73 ± 46.23% for 1.0 mg Q-MWF, p < 0.0001; and 48.25 ± 70.68% for 0.25 mg Q-MWF, p < 0.01). The percent change in C-telopeptide levels was not different among the treatment groups (p = 0.88). Baseline total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and cholesterol/HDL levels were also similar among treatment arms. There was no difference in the percent change for total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglyceride levels among the dose groups following letrozole intervention. Although a significant increase in cholesterol/HDL ratio was observed in the standard dose arm (6.13 ± 11.44%, p = 0.01), the change in cholesterol/HDL ratio was not different among the dose groups (p = 0.67). The baseline triglyceride levels were also different among the dose groups (p = 0.04) with the levels in the standard dose arm lower than those in the 2.5 mg Q-MWF arm. Even though there was a significant increase in triglycerides in the standard dose arm (27.45 ± 36.61%, p = 0.01), the percent change in triglycerides was not different among the treatment groups (p = 0.17).

Table 3.

Baseline serum C-telopeptide and lipids and percent change in C-telopeptide and lipids at the end of letrozole intervention.

| Baseline | % Change | p-valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-telopeptide, ng/ml | |||

| 2.5 mg QD | 0.53±0.46 | 47.67±70.86 | <0.01 |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 0.47±0.25 | 37.08±57.41 | <0.01 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 0.38±0.17 | 48.73±46.23 | <0.0001 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 0.39±0.23 | 48.25±70.68 | <0.01 |

| p-valueb | 0.21 | 0.88 | |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | |||

| 2.5 mg QD | 204±43 | 3.68±11.66 | 0.11 |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 204±39a | 3.36±13.49 | 0.22 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 198±35 | 2.17±13.85 | 0.47 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 207±28 | −1.75±14.40 | 0.57 |

| p-valueb | 0.86 | 0.47 | |

| LDL, mg/dL | |||

| 2.5 mg QD | 120±38 | 4.28±15.84 | 0.18 |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 117±30 | 5.83±23.68 | 0.23 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 114±31 | 2.28±19.37 | 0.59 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 122±26 | −1.68±18.53 | 0.67 |

| p-valueb | 0.82 | 0.58 | |

| HDL, mg/dL | |||

| 2.5 mg QD | 65±15 | −2.12±12.24 | 0.39 |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 60±17 | 1.01±14.04 | 0.72 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 64±15 | −0.69±13.01 | 0.81 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 62±16 | −1.78±12.46 | 0.50 |

| p-valueb | 0.63 | 0.82 | |

| Chol/HDL | |||

| 2.5 mg QD | 3.30±0.86 | 6.13±11.44 | 0.01 |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 3.57±0.81 | 3.96±17.61 | 0.26 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 3.16±0.63 | 3.41±11.09 | 0.16 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 3.55±0.97 | 0.91±17.28 | 0.80 |

| p-valueb | P=0.25 | P=0.67 | |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | |||

| 2.5 mg QD | 100±40 | 27.45±36.61 | 0.01 |

| 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 135±62 | 7.92±38.56 | 0.28 |

| 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 103±28 | 16.20±43.67 | 0.10 |

| 0.25 mg Q-MWF | 122±52 | 7.09±28.32 | 0.24 |

| p-valueb | 0.04 | 0.17 |

mean±standard deviation

test equality among the four groups based on one-way ANOVA

derived from paired t test for the % change within each group

The results of the quality-of-life responses at the end of letrozole intervention are summarized in Table 4. For the mental and physical domains of the SF-36 tool, no differences were observed in the proportion of women who experienced worsened, stable, and improved QoL scores among the treatment groups. For MENQOL assessment, the majority of study participants did not experience a clinically meaningful change in the QoL scores within the psychosocial, physical, or sexual domains. No differences were observed in the proportion of women who had worsened, stable, or improved QoL scores among the dose groups for each domain assessed in MENQOL.

Table 4.

Quality-of-life response analyses at the end of letrozole interventiona

| 2.5 mg QD | 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 0.25 mg Q-MWF | Pb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Improved (%) |

Stable (%) |

Worsen (%) |

Improved (%) |

Stable (%) |

Worsen (%) |

Improved (%) |

Stable (%) |

Worsen (%) |

Improved (%) |

Stable (%) |

Worsen (%) |

|

| SF-36 | |||||||||||||

| Mental Component summary | 17.9 | 78.6 | 3.6 | 26.9 | 53.9 | 19.2 | 4.4 | 73.9 | 21.7 | 29.6 | 63.0 | 7.4 | 0.19 |

| Physical Component summary | 18.5 | 70.4 | 11.1 | 26.9 | 50.0 | 23.1 | 12.5 | 75.0 | 12.5 | 18.5 | 59.3 | 22.2 | 0.60 |

| Mental health | 17.9 | 67.9 | 14.3 | 26.9 | 46.2 | 26.9 | 8.3 | 66.7 | 25.0 | 25.9 | 66.7 | 7.4 | 0.23 |

| Role-physical | 14.8 | 70.4 | 14.8 | 23.1 | 57.7 | 19.2 | 4.2 | 91.7 | 4.2 | 22.2 | 66.7 | 11.1 | 0.21 |

| Bodily pain | 17.9 | 50.0 | 32.1 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 23.1 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 29.6 | 40.7 | 29.6 | 0.78 |

| Role-emotional | 7.4 | 85.2 | 7.4 | 30.7 | 61.5 | 7.7 | 4.2 | 80.3 | 12.5 | 22.2 | 74.1 | 3.7 | 0.11 |

| Physical function | 32.1 | 42.9 | 25.0 | 26.9 | 65.4 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 91.7 | 8.3 | 22.2 | 55.6 | 22.2 | 0.12 |

| Vitality | 32.1 | 42.9 | 25.0 | 38.5 | 34.6 | 26.9 | 8.3 | 54.2 | 37.5 | 22.2 | 55.6 | 22.2 | 0.22 |

| General health | 17.9 | 78.6 | 3.6 | 15.4 | 73.1 | 11.5 | 8.3 | 83.3 | 8.3 | 14.8 | 63.0 | 22.2 | 0.45 |

| Social function | 3.6 | 75.0 | 21.4 | 19.2 | 57.7 | 23.1 | 4.2 | 87.5 | 8.3 | 25.9 | 55.6 | 18.5 | 0.07 |

| MENQOL | |||||||||||||

| Vasomotor | 17.9 | 39.3 | 42.9 | 30.8 | 38.5 | 30.8 | 20.8 | 33.3 | 45.8 | 7.7 | 38.5 | 53.9 | 0.49 |

| Psycho-social | 35.7 | 60.7 | 3.6 | 34.6 | 50.0 | 15.4 | 12.5 | 62.5 | 25.0 | 34.6 | 46.2 | 19.2 | 0.16 |

| Physical | 25.0 | 53.6 | 21.4 | 26.9 | 50.0 | 23.1 | 16.7 | 58.3 | 25.0 | 15.4 | 50.0 | 34.6 | 0.88 |

| Sexual | 17.9 | 60.7 | 21.4 | 26.9 | 50.0 | 23.1 | 8.3 | 70.8 | 20.8 | 23.1 | 50.0 | 26.9 | 0.67 |

The response analysis was based on the proportion of women having worsened (SF-36 score, ≥5-point decrease; MENQOL score, ≥0.5-point increase), improved (SF-36 score, ≥5-point increase; MENQOL, ≥0.5-point decrease) or stable QoL relative to baseline.

Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the response results on each domain of quality of life between the four dose groups.

Safety data analysis was implemented on all study participants. Table 5 summarizes the frequency of self-reported AEs. The majority of participants reported at least one AE. The prevalence of participants with AEs deemed possibly, probably, and definitely related to letrozole intervention differed significantly among the treatment arms (p = 0.04) with 60.7%, 35.7%, 71.4, 64.3% of participants reporting related AEs for 2.5 mg QD, 2.5 mg Q-MWF, 1.0 mg Q-MWF, and 0.25 mg Q-MWF, respectively. However, the frequency of related AEs did not appear dose dependent.

Table 5.

Self-reported adverse events.

| Event | 2.5 mg QD | 2.5 mg Q-MWF | 1.0 mg Q-MWF | 0.25 mg Q-MWF | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 28 (100%)a | 27 (96.4%) | 27 (96.4%) | 28 (100%) | 1.00 |

| Related AEc | 17 (60.7%) | 10 (35.7%) | 20 (71.4%) | 18 (64.3%) | 0.04 |

| Any SAE | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.90 |

N (%of total)

derived from Fisher’s exact test

including possibly, probably and definitely related AEs

Discussion

In this double-blind, randomized clinical trial of high-risk postmenopausal women, effective estrogen suppression was demonstrated across all dosing regimens of letrozole: 2.5 mg daily, 2.5 mg Q-MWF, 1 mg Q-MWF, 0.25 mg Q-MWF. Following 24 weeks of treatment, estrogen suppression averaging between 75 – 78% and 86 – 93% from baseline, was observed for serum E2 and E1 levels, respectively. The extent of estrogen suppression with low and intermittent letrozole doses was non-inferior to the standard daily dose. Estrogen suppression in the standard dose arm was observed six weeks following drug discontinuation, with E2 and E1 levels suppressed by 29% and 40% from baseline, respectively. The recuperation of estrogen levels 6 weeks after letrozole discontinuation occurred in all treatment arms with a trend favoring dose-dependency.

Our study also examined whether low and intermittent letrozole doses would affect rates of bone resorption. Increased bone resorption with letrozole therapy poses a significant problem for postmenopausal women who are already at increased risk for developing osteoporosis. C-telopeptide, a cross-linked peptide of type I collagen [23], is a sensitive serum biochemical marker released during bone resorption and correlates inversely with bone mineral density response to AI therapy. Therapy related response using C-telopeptide levels can be determined within 3 to 6 months of therapy rather than 1 to 2 years, as demonstrated with DEXA scans. Harper-Wynne et al. showed that 3 months of standard letrozole therapy leads to increased bone resorption, as measured by C-telopeptide levels [24]. In our study, we demonstrate that C-telopeptide levels increased significantly from baseline in all dose groups. The increase in C-telopeptide levels was similar among the letrozole dose groups, suggesting that low and intermittent doses had similar adverse effects on bone resorption compared to standard dose. Because the inhibition of aromatase impacts normal physiological processes associated with steroid hormones [25, 26], we examined the effects of different letrozole dosing regimens on lipid profile. There were no significant changes noted in cholesterol levels for each dose arm. The finding of minimal changes in serum lipids is consistent with results from prior placebo controlled trials [27, 28].

We assessed QoL measures related to menopausal symptoms and general health using two validated questionnaires. Our results revealed no significant difference in QoL impact by dose arm at the end of the intervention for either the SF-36 or the MENQOL. The impact of the standard dose of letrozole compared with placebo on QoL was assessed in the MA.17 trial using SF-36 and MENQOL scores [21]. The study showed that the standard letrozole dose did not have an adverse impact on overall QoL. Small effects were seen in some domains consistent with a minority of patients experiencing changes in QoL compatible with a reduction of estrogen synthesis. Such small effects are not likely detectable with the sample size incorporated in our study.

Of the 112 participants, one, three, four, and three participants discontinued intervention early due to AEs in the standard dose (2.5 mg QD), the 2.5 mg Q-MWF, 1.0 mg Q-MWF, and 0.25 mg Q-MWF arms, respectively. The presence of adverse effects to result in early termination was noted in each dose group but the number of early drop-outs did not show a consistent dose relationship. There was a significant difference in the frequency of self-reported related AEs among the dose arms, although the frequency did not appear to be dose dependent.

There are some limitations with our study. We chose to measure the suppression in E2 levels as the primary endpoint because E2 is the most biologically active estrogen. However, letrozole intervention in all treatment arms effectively suppressed estrogens, resulting in post-intervention E2 levels below the limit of detection in 64–67% of the participants and E1 levels below the limit of detection in 53–63% of participants. Suppression of estrogen levels below the limit of detection may have limited our ability to detect differences among treatment arms. Future studies should consider the measurement of estrone sulfate to differentiate the extent of estrogen suppression as estrone sulfate is rarely suppressed below the limit of detection [29]. Furthermore, the study was adequately powered for evaluation of estrogen suppression by non-inferiority test but not powered for evaluation of secondary endpoints. It is possible that the lack of significant differences in AEs and QoL measures is related to the small sample size. In addition, the study duration of 24 weeks was adequate to evaluate estrogen suppression, but may not be long enough to observe changes in AEs and QoL. Another limitation is that a univariate non-inferiority test does not adjust for potential confounders such as age and BMI in regards to estrogen suppression.

We conclude that low and intermittent doses of letrozole (as low as 1/24th of the total dose received in the standard dose arm) were not inferior to the standard dose in estrogen suppression at the end of agent intervention. The effective estrogen suppression with low and intermittent letrozole doses was accompanied by similar adverse effects on C-telopeptide levels when compared to standard dose. The changes in QoL and self-reported AEs were also similar among the dose groups. Future studies should characterize the relationship between the extent of systemic estrogen suppression and breast tissue drug activity and side effects to evaluate the feasibility of selecting an AI dose/schedule for effective estrogen suppression with a favorable side effect profile.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by a contract (N01CN35158 to HHS Chow) from the National Cancer Institute and the Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant (CA023074).

The authors thank Valerie Butler, Heidi Fritz, Bettina Hofacre, Samantha Castro, Jean Jensen, Wade Chew, Catherine Cordova, Steve Rodney, and Jose Guillen-Rodriguez for their excellent assistance in the performance of the clinical study and endpoint assays.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no Conflict of Interest to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01077453

References

- 1.Clemons M, Goss P. Estrogen and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:276–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF investigators AL. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative G. Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Bradley R, Ingle J, Aihara T, Bliss J, Boccardo F, Coates A, Coombes RC, et al. Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:1341–1352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, Dowsett M, Knox J, Cawthorn S, Saunders C, Roche N, Mansel RE, von Minckwitz G, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Ales-Martinez JE, Cheung AM, Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, McTiernan A, Robbins J, Johnson KC, Martin LW, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381–2391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huiart L, Ferdynus C, Giorgi R. A meta-regression analysis of the available data on adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer: summarizing the data for clinicians. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:325–328. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:459–478. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon JM, Renshaw L, Young O, Murray J, Macaskill EJ, McHugh M, Folkerd E, Cameron DA, A’Hern RP, Dowsett M. Letrozole suppresses plasma estradiol and estrone sulphate more completely than anastrozole in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1671–1676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler J, Helle H, Ekse D, Duong NK, Evans DB, Nordbo Y, Aas T, Lonning PE. Letrozole is superior to anastrozole in suppressing breast cancer tissue and plasma estrogen levels. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6330–6335. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisler J, Haynes B, Anker G, Dowsett M, Lonning PE. Influence of letrozole and anastrozole on total body aromatization and plasma estrogen levels in postmenopausal breast cancer patients evaluated in a randomized, cross-over study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:751–757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demers LM, Lipton A, Harvey HA, Kambic KB, Grossberg H, Brady C, Santen RJ. The efficacy of CGS 20267 in suppressing estrogen biosynthesis in patients with advanced stage breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;44:687–691. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipton A, Demers LM, Harvey HA, Kambic KB, Grossberg H, Brady C, Adlercruetz H, Trunet PF, Santen RJ. Letrozole (CGS 20267). A phase I study of a new potent oral aromatase inhibitor of breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:2132–2138. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2132::aid-cncr2820750816>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bisagni G, Cocconi G, Scaglione F, Fraschini F, Pfister C, Trunet PF. Letrozole, a new oral non-steroidal aromastase inhibitor in treating postmenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer. A pilot study. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:99–102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajetta E, Zilembo N, Dowsett M, Guillevin L, Di Leo A, Celio L, Martinetti A, Marchiano A, Pozzi P, Stani S, Bichisao E. Double-blind, randomised, multicentre endocrine trial comparing two letrozole doses, in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:208–213. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buzdar AU, Robertson JF, Eiermann W, Nabholtz JM. An overview of the pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of the newer generation aromatase inhibitors anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane. Cancer. 2002;95:2006–2016. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iveson TJ, Smith IE, Ahern J, Smithers DA, Trunet PF, Dowsett M. Phase I study of the oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor CGS 20267 in healthy postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:324–331. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.2.8345035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, van Maris B, Ross A, Franssen E, Guyatt GH, Norton PG, Dunn E. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24:161–175. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)82006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. Book How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. City: QualityMetric; 2000. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson RE, Grebe SK, DJOK, Singh RJ. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of estradiol and estrone in human plasma. Clin Chem. 2004;50:373–384. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moal V, Mathieu E, Reynier P, Malthiery Y, Gallois Y. Low serum testosterone assayed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Comparison with five immunoassay techniques. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;386:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whelan TJ, Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pater JL, Tu D, Pritchard K, Liu S, Shepherd LE, Palmer M, Robert NJ, et al. Assessment of quality of life in MA. 17: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of letrozole after 5 years of tamoxifen in postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6931–6940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maunsell E, Goss PE, Chlebowski RT, Ingle JN, Ales-Martinez JE, Sarto GE, Fabian CJ, Pujol P, Ruiz A, Cooke AL, et al. Quality of life in MAP.3 (Mammary Prevention 3): a randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating exemestane for prevention of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1427–1436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garnero P. Biomarkers for osteoporosis management: utility in diagnosis, fracture risk prediction and therapy monitoring. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12:157–170. doi: 10.1007/BF03256280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harper-Wynne C, Ross G, Sacks N, Salter J, Nasiri N, Iqbal J, A’Hern R, Dowsett M. Effects of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole on normal breast epithelial cell proliferation and metabolic indices in postmenopausal women: a pilot study for breast cancer prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:614–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:225–230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goss PE. Risks versus benefits in the clinical application of aromatase inhibitors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:325–332. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cigler T, Tu D, Yaffe MJ, Findlay B, Verma S, Johnston D, Richardson H, Hu H, Qi S, Goss PE. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCIC CTG MAP1) examining the effects of letrozole on mammographic breast density and other end organs in postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0662-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasan KM, Goss PE, Pritchard PH, Shepherd L, Palmer MJ, Liu S, Tu D, Ingle JN, Heath M, Deangelis D, Perez EA. The influence of letrozole on serum lipid concentrations in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer who have completed 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen (NCIC CTG MA. 17L) Ann Oncol. 2005;16:707–715. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geisler J, Lonning PE. Endocrine effects of aromatase inhibitors and inactivators in vivo: review of data and method limitations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;95:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]