Abstract

Background

Environmental enteropathy (EE) is a subclinical enteric condition found in low-income countries that is characterized by intestinal inflammation, reduced intestinal absorption, and gut barrier dysfunction. We aimed to assess if EE impairs the success of oral polio and rotavirus vaccines in infants in Bangladesh.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational study of 700 infants from an urban slum of Dhaka, Bangladesh from May 2011 to November 2014. Infants were enrolled in the first week of life and followed to age one year through biweekly home visits with EPI vaccines administered and growth monitored. EE was operationally defied as enteric inflammation measured by any one of the fecal biomarkers reg1B, alpha-1-antitrypsin, MPO, calprotectin, or neopterin. Oral polio vaccine success was evaluated by immunogenicity, and rotavirus vaccine response was evaluated by immunogenicity and protection from disease. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01375647.

Findings

EE was present in greater than 80% of infants by 12 weeks of age. Oral poliovirus and rotavirus vaccines failed in 20.2% and 68.5% of the infants respectively, and 28.6% were malnourished (HAZ < − 2) at one year of age. In contrast, 0%, 9.0%, 7.9% and 3.8% of infants lacked protective levels of antibody from tetanus, Haemophilus influenzae type b, diphtheria and measles vaccines respectively. EE was negatively associated with oral polio and rotavirus response but not parenteral vaccine immunogenicity. Biomarkers of systemic inflammation and measures of maternal health were additionally predictive of both oral vaccine failure and malnutrition. The selected biomarkers from multivariable analysis accounted for 46.3% variation in delta HAZ. 24% of Rotarix® IgA positive individuals can be attributed to the selected biomarkers.

Interpretation

EE as well as systemic inflammation and poor maternal health were associated with oral but not parenteral vaccine underperformance and risk for future growth faltering. These results offer a potential explanation for the burden of these problems in low-income problems, allow early identification of infants at risk, and suggest pathways for intervention.

Funding

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1017093).

Keywords: Environmental enteropathy, Malnutrition, Oral vaccine failure

Highlights

-

•

Environmental enteropathy was present in the majority of Dhaka slum children at 12 weeks of age.

-

•

Growth in the first year of life was negatively impacted by environmental enteropathy

-

•

Oral vaccine response, but not parenteral vaccine response, was negatively impacted by environmental enteropathy

-

•

Biomarkers predictive of malnutrition and vaccine failure fell into three clusters: gut inflammation, systemic inflammation and maternal factors.

Malnutrition and oral vaccine failure are common in infants living in unsanitary conditions in low income countries. We hypothesized that exposure to infections of the gut at an early age could result in an inflammatory condition of the intestine termed Environmental Enteropathy (EE), and that this in turn could contribute to malnutrition and vaccine response. Children from an urban slum in Dhaka Bangladesh were enrolled within the first week of life, and vaccine response and growth measured to age one year. Most children were infected by two or more enteric infections and had the characteristic inflammation of EE. Both malnutrition and oral vaccine failure were associated with EE. We concluded that improvement in child health in low income countries will likely require prevention or treatment of gut damage due to infection.

1. Introduction

Environmental enteropathy (EE) is a subclinical yet apparently common illness in low income countries that is characterized by small intestine inflammation with shortened villi, intestinal barrier dysfunction, and reduced nutrient absorption (Korpe and Petri, 2012, Campbell et al., 2003, McKay et al., 2010). EE is associated with poverty and unsanitary living conditions, and hypothesized to be caused by repeated or chronic exposure to enteropathogens and by malnutrition (Korpe and Petri, 2012).

EE in turn is suspected to contribute to the development of malnutrition and hinder its treatment, via small intestinal damage and resulting inflammation (Korpe and Petri, 2012, Prendergast and Kelly, 2012). Vaccines against enteric pathogens such as rotavirus and poliovirus have shown lower efficacy in developing countries, particularly in malnourished populations (Haque et al., 2014, Levine, 2010, Grassly et al., 2006, Zaman et al., 2010), suggesting that oral vaccine response could be adversely affected by EE.

The primary objective of the PROVIDE study was to test the hypothesis that there is an association between EE and impaired performance of the oral polio vaccine (OPV) and rotavirus vaccine in Bangladesh. A set of fecal proteins were used as biomarkers to noninvasively measure EE surrounding the time of vaccination. Myeloperoxidase, calprotectin, and neopterin were chosen to represent enteric inflammation, while alpha-1 anti-trypsin and reg1B were chosen to represent compromised intestinal epithelial integrity. In addition, biomarkers of nutrition and systemic inflammation, socioeconomic status, and maternal health were measured. Nutritional status was assessed by micronutrients and anthropometry measurements. Systemic inflammation was evaluated with inflammatory and regulatory cytokines, acute phase proteins (CRP, ferritin), and sCD14 (Supplemental Table 1). The primary outcomes were OPV serum neutralizing antibody titers and Rotarix® IgA titer, and Rotarix® success. Antibody titers were evaluated as a continuous variable. Secondary outcomes were growth as measured by HAZ and WAZ over one year.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study design and recruitment of the PROVIDE cohort has been described previously (Kirkpatrick et al., 2015a, Kirkpatrick et al., 2015b). In brief, a birth cohort of 700 infants from the Mirpur urban slum in Dhaka, Bangladesh were recruited and followed by twice weekly household visits and scheduled clinic visits over the first 2 years of life. All EPI-approved vaccines were administered by the study staff, and half of the infants were randomized to receive the Rotarix® vaccine. There was rolling admission of subjects over the first 18 months and the study spanned from May 2011–November 2014. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the ICDDR,B (FWA 00001468) and the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Virginia (FWA 00006183) and the University of Vermont (FWA 00000727). The PROVIDE cohort data has been utilized to assess Rotarix® efficacy (Kirkpatrick et al., 2015b).

2.2. Biomarker Selection and Definition

Biomarkers measured were selected to report on environmental factors postulated to affect nutrition and vaccine response: enteric inflammation, systemic inflammation, nutrition, socioeconomics, maternal health, and sanitation (Supplemental Table 1). These groupings did not affect the outcome of the statistical results.

2.3. Measurement of Vaccine Response and Malnutrition

Vaccine immunogenicity was measured in plasma at 18 and/or 52 weeks of age, and Rotarix® success was measured as protection from rotavirus diarrhea from weeks 18–52 in vaccinated infants (Supplemental Table 2). Height and weight were measured at enrollment and at every clinic visit using a Seca 354 Digital Baby Scale and Seca 416 Infantometer. Weight for age (WAZ), weight for height (WHZ), and height for age (HAZ) were measured using the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study Child Growth Standards (The World Health Organisation, the United Nations Children's Fund's, 2009). The change in HAZ and WAZ was calculated by subtracting the enrollment from the 52 week values.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Univariate linear or logistic regression analyses for continuous or binary responses (Rotarix® success only) were performed to evaluate the marginal effect of individual biomarker on the responses. False Discovery Rate (FDR) was used to correct for multiple comparisons with potentially informative biomarkers identified with a 20% FDR cutoff. Multivariable regression analysis with the Smoothly Clipped Absolute Deviation (SCAD) regularization was conducted to identify predictive biomarkers jointly, and the final model for each response was determined based on the optimal tuning parameter using 10-fold cross-validation criteria. Given several dozens of available biomarkers as potential predictors, traditional variable selection methods such as stepwise regression may not be practical or less efficient. Modern penalized regression methods, such as LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) or SCAD, can effectively identify the subset of biomarkers that are truly informative for the responses of interest (Tibshirani, 1996, Fan and Li, 2001). By imposing some penalty in the regression model fitting, these penalized methods can shrink the coefficients of those unimportant biomarkers to zero while retain those important ones. Note that a biomarker has an effect on a response if and only if its coefficient is nonzero. Thus the final models shall include all important biomarkers with parsimonious representation, enhanced interpretability, and improved prediction precision. The SCAD method was used in this study for its better statistical properties of variable selection and parameter estimation. All the SCAD analyses were performed using the “grpreg” package in R 3.1 (www.r-project.org). In addition, the hierarchical clustering analysis of biomarkers was performed to classify and present biomarkers graphically according to their correlated structure and similarity patterns. The function “hclustvar” in the R package “ClustOfVar” was used in the clustering analysis (www.r-project.org). The method can accommodate a mixture of quantitative and qualitative variables and classify those strongly correlated or similar biomarkers into the same clusters using homogeneity criterion (Chavent et al., 2011). Besides clustering analysis and multivariable analysis with SCAD as indicated, all other statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Cohort

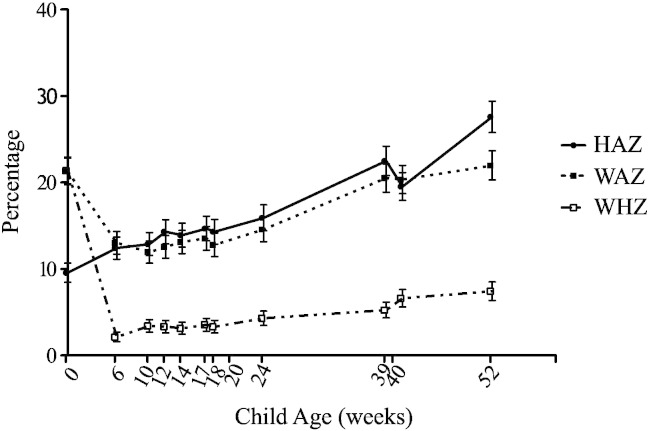

At enrollment the average age was 4.9 days of age, average HAZ and WAZ were − 0·90 and − 1·29 respectively. 28.9% of mothers were illiterate. Average monthly family income was 13,000 Taka (169 US dollars). Breastfeeding was nearly universal up to one year of age, with an exclusive breastfeeding taking place for an average 120 days. Over the first year of life infants with stunting (HAZ < − 2) increased from 9.5% at enrollment to 27.6%, with 22% of the infants underweight (WAZ < − 2) and 7.4% wasted (WHZ < − 2) at week 52 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Anthropometry over the first 52 weeks of life. Height and weight were taken at scheduled clinic visits, and transformed to standardized z-scores. The X axis depicts the age of the child, the Y axis depicts the percentage of infants in the cohort who had a HAZ, WAZ, or WHZ of <− 2.

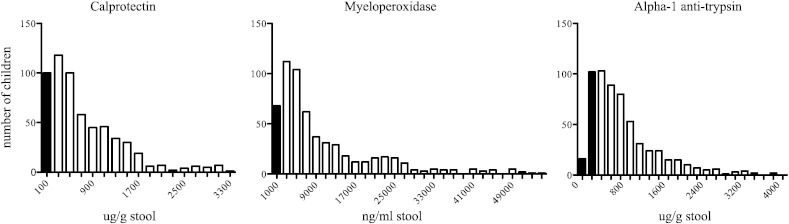

3.2. Enteric Inflammation Was Prevalent at 12 weeks of Age

Stool samples at 12 weeks of age were analyzed for biomarkers of EE. Fecal measures myeloperoxidase (MPO) and calprotectin, markers of neutrophil inflammation and biomarkers of inflammatory bowel disease, were abnormal in 82% and 94% of the infants respectively. Fecal alpha-1-antitrypsin was also elevated in 82% of the infants (Fig. 2). We concluded that the majority of the infants had evidence of enteric inflammation by 12 weeks of age.

Fig. 2.

Environmental enteropathy in infants. Frequency distribution of fecal calprotectin, myeloperoxidase, and alpha-1 anti-trypsin at age 12 weeks using ELISA. Black columns represent normal values, and white columns represent abnormal values. Normal values were based on Western standards: calprotectin > 200 μg/g (82.7% elevated), myeloperoxidase > 2000 ng/ml (88.1% elevated), alpha-1 anti-trypsin is > 270 μg/g (81.9% elevated).

Calprotectin n = 596, MPO n = 591, alpha-1 anti-trypsin n = 592.

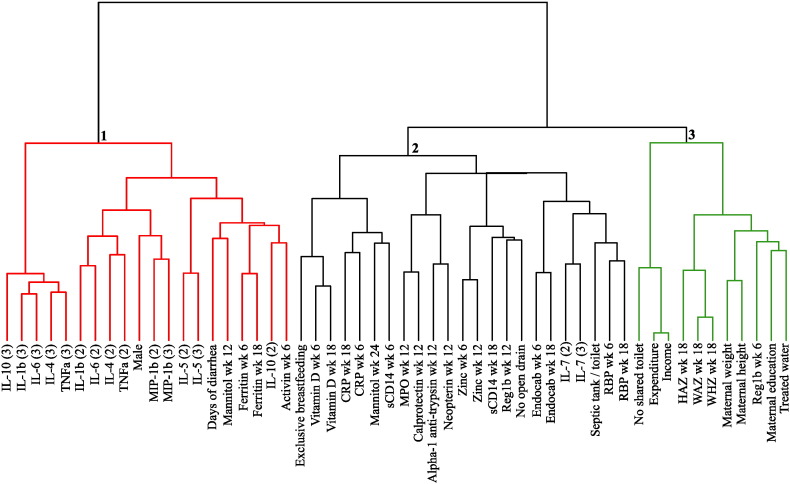

3.3. Clustering Analysis of the Biomarkers

The relationships among biomarkers were explored by a cluster analysis. There were three major clusters among all the biomarkers (Fig. 3). Cluster 1 included days of diarrhea through week 18 and was dominated by systemic inflammatory biomarkers, particularly plasma cytokines and the acute phase reactant ferritin; mannitol absorption was also in this cluster. Cluster 2 contained all of the biomarkers considered evidence of enteric inflammation (fecal reg1B, alpha-1-antitrypsin, MPO, calprotectin, and neopterin), micronutrients, and two systemic inflammatory biomarkers, sCD14 and CRP (potentially reflecting bacterial translocation from the gut). Two of the four sanitation markers (the absence of an open sewer and access to a toilet/septic tank) were also in Cluster 2. Cluster 3 comprised maternal health biomarkers including mother's height, weight, and education, HAZ at 18 weeks, and socioeconomic measures including income, access to treated water, and no shared toilet. The intestinal regeneration biomarker fecal reg1B at 6 weeks of age was also present in cluster 3.

Fig. 3.

Cluster dendrogram of biomarkers. Biomarkers are clustered according to relatedness; adjacent markers are the most closely correlated, while increased distance indicates decreasing correlations. Biomarker clusters are numbered 1 (systemic inflammation), 2 (enteric inflammation and malabsorption), and 3 (maternal health).

3.4. EE Was Associated With OPV and Rotarix® Underperformance and Failure but Not Parenteral Vaccine Underperformance and With Malnutrition

Based on the results from the cluster analysis, reg1B, calprotectin, neopterin, MPO, and alpha-1 antitrypsin were considered as biomarkers of EE. Biomarkers of EE measured during the time of vaccination were tested by multivariable analysis for association with outcomes of vaccine response and nutrition. EE was associated with the infants' response to OPV2 (fecal reg1B), OPV3 (fecal reg1B and calprotectin), Rotarix® IgA (fecal alpha-1-antitrypsin), and Rotarix® success (fecal reg1B and neopterin) (Table 1). While other biomarkers on cluster 2 associated with these parenteral-administered vaccines, biomarkers of EE were not associated with the response to the vaccines tetanus, pertussis, diphtheria, Haemophilus influenza type B and measles (Table 1). EE biomarkers fecal reg1B and MPO were also negatively associated with changes in WAZ and HAZ from enrollment to age one year (Table 1). Univariate analysis also revealed that markers of enteric inflammation, including the EE biomarkers, associated with change in WAZ and HAZ (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

SCADa-selected biomarkers and coefficients. Direction of association is indicated by (+) or (−) next to biomarker name. Vaccination “outcome” refers to the detectable antibody titer of the indicated vaccine.

| Outcomes | Cluster 1 biomarkers | Cluster 2 biomarkers | Cluster 3 biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHAZ (n = 498) |

Days of diarrhea (−) | Reg1B week 12 (−) | Expenditure (+) |

| Mannitol (−) | MPO (−) | Maternal height (+) | |

| Ferritin week 18 (−) | CRP week 6 (−) | Access to treated water (+) | |

| sCD14 week 6 (−) RBP week 6 (+) vitamin D (−) Zinc (−) | WAZ week 18 (+) | ||

| ΔWAZ (n = 498) |

Ferritin week 18 (−) | Reg1B week 12 (−) | Maternal education (+) |

| IL-1β (2) (−) | MPO week 12 (−) | Maternal weight (+) | |

| IL-1β (3) (−) | CRP week 6 (−) | Access to treated water (+) | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (−) | HAZ week 18 (+) | ||

| Zinc week 6 (−) | WHZ week 18 (+) | ||

| OPV1 (n = 509) |

sCD14 week 6 (−) | ||

| sCD14 week 18 (+) | Maternal education (+) | ||

| OPV2 (n = 509) |

Ferritin week 6 (−) | RBP week 6 (+) | |

| Zinc week 6 (+) | Reg1β week 6 (−) | ||

| Access to Septic tank/toilet (+) | WAZ week 18 (+) | ||

| OPV3 (n = 509) |

Mannitol week 12 (−) | Reg1β week 12 (−) | |

| Calprotectin week 12 (+) | Maternal height (+) | ||

| WHZ week 18 (+) | |||

| Rotarix IgA (n = 261) |

IL-10 (2) (−) | Alpha-1 anti-trypsin (−) | |

| IL-10 (3) (+) | Exclusive breastfeeding (−) | ||

| Vitamin D week 6 (+) | |||

| Rotarix Success (n = 261) |

Male (−) | Reg1β week 12 (+) | Reg1β week 6 (+) |

| Neopterin week 12 (−) | Maternal education (+) | ||

| sCD14 week 6 (−) | |||

| RBP week 6 (−) | |||

| Vitamin D week 18 (−) | |||

| Zinc week 18 (+) | |||

| Tetanus week 18 (n = 510) |

Days of diarrhea (+) | Endocab week 18 (+) | WAZ week 18 (+) |

| IL-6 (2) (+) | sCD14 week 18 (+) | ||

| IL-6 (3) (+) | RBP week 6 (+) | ||

| RBP week 18 (+) | |||

| Tetanus Week 52 (n = 481) |

Ferritin week 6 (+) | sCD14 week 18 (−) | Maternal weight (+) |

| Expenditure (+) | |||

| WAZ week 18 (+) | |||

| Pertussis—Ptx (n = 481) |

Ferritin week 6 (+) | CRP week 18 (−) | Maternal weight (+) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (+) | Income (+) | ||

| WHZ week 18 (+) | |||

| Diphtheria (n = 481) |

Ferritin week 6 (+) | WAZ week 18 (+) | |

| Activin week 6 (+) | |||

| HiB (n = 481) |

Days of diarrhea (+) | Septic tank/toilet (−) | WAZ week 18 (+) |

| Mannitol week 12 (−) | WHZ week 18 (+) | ||

| Measles (n = 481) |

Endocab week 6 (−) | ||

| sCD14 week 6 (+) | |||

| sCD14 week 18 (−) | |||

| RBP week 18 (−) | |||

| Vitamin D week 6 (+) |

Smoothly Clipped Absolute Deviation (SCAD) was applied for the multivariable analysis to identify a small subset of important biomarkers. SCAD imposes a penalty in the regression model to shrink small coefficients of unimportant biomarkers to zero and retain important biomarkers in the model, simultaneously producing coefficient estimates for the selected biomarkers.

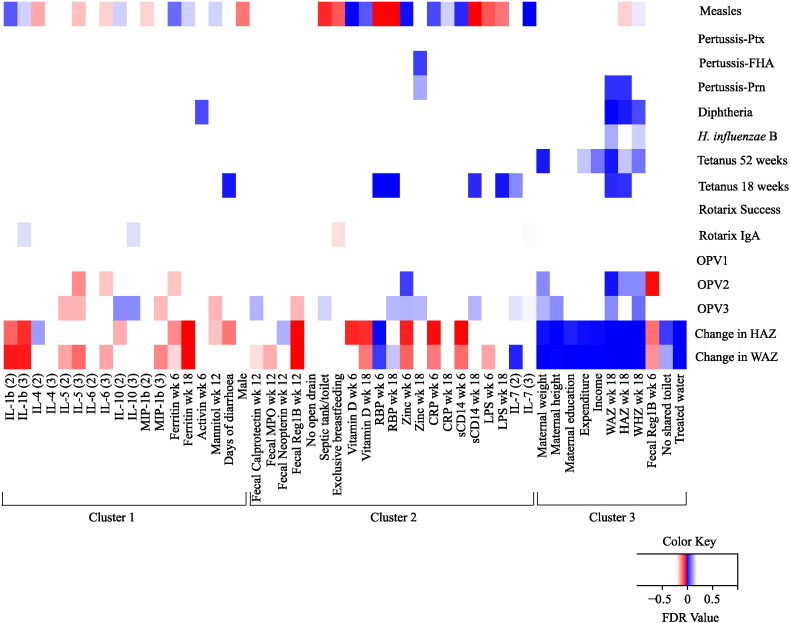

Fig. 4.

Heatmap of FDR values from univariate linear regression analysis. Biomarkers with a FDR value of 0.2 or below for at least one outcome are depicted on the heatmap. Markers are grouped according to hierarchal cluster results. A positive correlation is indicated by a blue box, and a negative correlation is indicated by a red box. Color patterns reveal associations of biomarkers with outcomes, indicating an improvement or worsening of response. An FDR value close to 0 indicates a strong correlation. Color intensity is indicative of FDR value: darker colors are closer to 0.

Not every biomarker of EE was selected by multivariable analysis, likely due to the fact that they were clustered, but notably reg1B was predictive of OPV2, OPV3, and Rotarix® success. Univariate analysis, likely by virtue of only considering the marginal effect, revealed fewer EE biomarkers than the multivariable SCAD analysis that considered the joint effect (Fig. 4). One biomarker postulated to be a measure of EE, the lactulose:mannitol ratio, was unable to be measured in this cohort due to a naturally occurring substance in the urine of infants that co-eluted with lactulose on HPIC (data not shown).

3.5. Systemic Inflammation Was Associated With Oral and Parenteral Vaccine Response and With Malnutrition

As opposed to fecal EE biomarkers, systemic inflammatory markers were associated with parenteral and oral vaccine responses, as well as with nutrition by multivariable analyses. Cluster 1 systemic biomarkers and their associated vaccine outcomes were: ferritin (OPV2, tetanus, pertussis, diphtheria ΔWAZ, ΔHAZ), IL-10 (Rotarix® IgA), activin (diphtheria), and IL-1b (ΔWAZ) (Table 1). CRP (pertussis, ΔWAZ) and sCD14 (OPV1, measles, tetanus, Rotarix® success, ΔHAZ) from cluster 2 were also associated with some outcomes. Many of the systemic biomarkers identified were positively associated with parenteral vaccine response, as opposed to the negative association with oral vaccine and nutrition.

3.6. Nutritional Status at the Time of Vaccination Was Associated With Oral and Parenteral Vaccine Response

Multivariable analysis demonstrated that malnutrition at the time of vaccination, as measured by WAZ, HAZ and/or WHZ, affected the response to every vaccine measured with the exception of Rotarix®, measles and OPV1. Not unexpectedly, 18 week nutritional status predicted that at one year of life (Table 1). Biomarkers of micronutrients were also associated with vaccine response, including retinol binding protein (RBP), zinc and ferritin for OPV2 and RBP, zinc and vitamin D for Rotarix®, and RBP and ferritin for tetanus. Change in HAZ and WAZ in turn was associated with RBP, vitamin D, zinc, and ferritin (Table 1).

3.7. Maternal Height and Weight Were Not Associated With Vaccine Response

While maternal malnutrition, as measured by height and weight, is known to predict infant malnutrition (as was the case for this study), this was not generally true for vaccine response, with only tetanus linked to maternal weight by multivariable analysis (Table 1); univariate analysis showed the same results, with an additional weak association with OPV3 (Fig. 4).

3.8. Quantifiable effect of biomarkers on Rotavirus and Malnutrition

Biomarkers selected by SCAD were analyzed for the ability to explain the variation seen in ΔHAZ and rotavirus vaccine-induced plasma IgA through evaluation of the attributable fraction of variance. For Rotarix® IgA the percent variance explained was approximately 24% while for ΔHAZ the biomarkers selected by multivariable analysis explained 46·3% of the observed variation.

To further understand the effect of EE during the first year of life, CRP elevation was evaluated for effect on change in HAZ from 0–52 weeks. CRP, a systemic inflammation biomarker that clusters with the EE biomarkers, was measured in the cohort at 6, 18, and 40 weeks, making it an ideal marker of sustained inflammation. Infants were classified into four groups: Group 0 consisted of those infants if none of their CRPs were elevated, Group 1 if one CRP measure was elevated, Group 2 if two CRPs were elevated and Group 3 if all three CRPs were elevated. Group 0 was considered as the reference in this analysis. Infants were found to be significantly more likely to have a negative change in HAZ if CRP was elevated at 2 or more time points (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of ΔHAZ by elevated CRP groups.

| CRP groupa | No. of children (%) | ΔHAZ | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 0: no elevated CRP | 102 (17.9) | − 0.40 ± 0.96 | Reference |

| Group 1: one elevated CRP | 178 (31.2) | − 0.47 ± 0.88 | 0.54 |

| Group 2: two elevated CRPsc | 186 (32.6) | − 0.65 ± 0.86 | 0.02 |

| Group 3: three elevated CRPsc | 104 (18.2) | − 0.75 ± 0.86 | 0.005 |

CRP was measured at weeks 6, 18 and 40 with median (25th to 75th quartile) as 0.24 (0.06 to 0.56), 0.62 (0.21 to 1.65), and 0.98 (0.20 to 3.42), respectively. An elevated CRP was defined as if the CRP measure was above the median for the week being measured.

Pairwise P-values from one-way ANOVA, where the differences of ΔHAZ among the four CRP groups were compared with Group 0 (the reference).

Sustained inflammation with respect to CRPs was defined as if at least two CRP measures were elevated. Significantly greater HAZ reductions were observed in children with sustained inflammation when compared to those with one or zero elevated CRP (pairwise P value = 0.04 and 0.009 for Groups 2 and 3, respectively).

4. Discussion

This prospective longitudinal study of infants in an urban slum from Bangladesh enabled analysis of the impact of EE at the time of vaccination on EPI vaccine response and nutrition. The most important finding was that EE was associated with failure of Rotarix® and underperformance of OPV but had no impact on the immunogenicity of the parenteral-administered EPI vaccines. Malnutrition was also associated with EE. The identification of EE as predictive of OPV and Rotarix® underperformance and malnutrition was all the more remarkable for the fact that over 80% of infants had EE, with over half demonstrating sustained inflammation associated with EE. That oral vaccine underperformance and malnutrition were both associated with EE suggests that gut damage induced by EE is common to their pathogenesis.

4.1. Three Pathways Affecting Vaccine Response and Growth

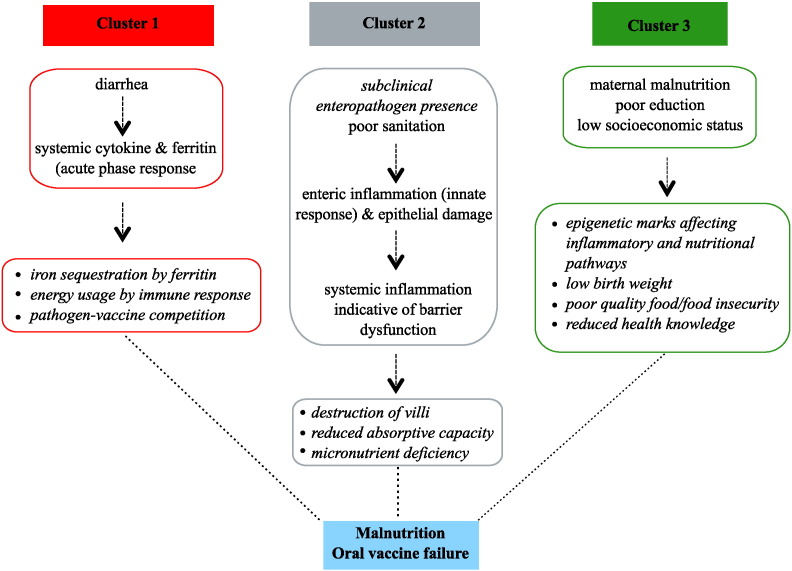

The clustering of biomarkers (Fig. 3) immediately suggested interrelated responses to environmental stressors (Fig. 5), with gut damage, inflammation, and maternal health as underlying processes common to oral vaccine failure and stunting.

Fig. 5.

Proposed pathways to oral vaccine underperformance and failure and malnutrition. Potential mechanisms are shown by which the three biomarker clusters [(1) systemic inflammation, (2) enteric inflammation, and (3) maternal health] could impact oral vaccines and nutrition.

Cluster 1 was comprised predominantly of markers of systemic inflammation and diarrheal disease. Diarrhea has been previously associated with growth faltering and OPV failure (Haque et al., 2014, Richard et al., 2013, Mondal et al., 2009, Myaux et al., 1996, Richard et al., 2014) and our work suggests this may be due in part to the development of systemic inflammation. We hypothesize that systemic inflammation as a result of diarrheal disease could contribute to oral vaccination underperformance by inhibiting attenuated live virus replication due to up-regulated antiviral responses. Systemic inflammation could contribute to malnutrition by activation of the anorexia-inducing activin-myostatin pathway (Han et al., 2013) as well as by consuming energy which otherwise could be used for growth. Ferritin levels were also negatively associated with growth. Ferritin is an acute phase protein and elevated levels likely indicate the presence of active infection; it is also possible that ferritin's role iron sequestration as a defense against pathogen assault results in reduced free iron for growth requirements (Wang et al., 2010).

Cluster 2 biomarkers included the EE biomarkers of gut damage and inflammation, as well as micronutrients, consistent with EE being associated with gut dysfunction. We previously had demonstrated that intestinal damage predicted growth faltering in infants in Bangladesh and Peru, as measured by fecal reg1B (Peterson et al., 2013). The current work validated and extended this observation by showing that oral vaccine underperformance and failure was also associated with enteric inflammation and damage. While unable to diagnose environmental enteropathy directly by small bowel biopsy, noninvasive measures in stool of epithelial damage (reg1B and alpha-1 antitrypsin), and enteric immune inflammation (myeloperoxidase, calprotectin, and neopterin) served as surrogates. These biomarkers were tightly clustered, supporting their use as measures of EE. Previous studies focused on nutrition but not vaccine response found that increased fecal alpha-1 anti-trypsin, MPO and neopterin were associated with linear growth defects (Kosek et al., 2013). The micronutrients zinc and vitamins A and D were also on cluster 2, consistent with environmental enteropathy-induced malabsorption which would further lead to growth faltering and poor immune function (Korpe and Petri, 2012, Richard et al., 2014, Han et al., 2013).

Cluster 3 represents a pathway centered on the health and socioeconomic status of the mother. Maternal height and nutrition is known to be associated with child mortality and growth, an association not seen with paternal height (Ozaltin et al., 2010, Di Cesare et al., 2015). Novel to this study was the finding that cluster 3 was associated with OPV1 (maternal education) and tetanus (maternal weight). Children born to short mothers are significantly more likely to have a low birth-weight, become stunted, and to die before five years of age (Black et al., 2008). Intrauterine nutrient availability as well as transgenerational epigenetic effects (Dominguez-Salas et al., 2014, Wu et al., 2004) could act to affect a child's nutritional status. Additionally, the educational status of women has been found to have twice the effect of that of males education on a child's overall health (Christiaensen and Alderman, 2004).

Strikingly, the EE biomarkers associated with oral vaccine underperformance and malnutrition did not associate with parenteral vaccine performance. Parenteral vaccine biomarkers were instead composed mainly of nutritional and systemic inflammatory biomarkers. Measles displayed variable directional associations. While univariate analysis revealed associations in all clusters, the strongest associations were seen in cluster 2, a result complimented by the SCAD selection. In common with the other parenteral vaccines there was no association of any enteric inflammation biomarkers. Instead, associations are strongest with micronutrients and acute phase proteins. In contrast to oral vaccine response, RBP had a negative effect on measles antibody response. The effect of vitamin A on measles seroconversion is unclear, with at least one paper demonstrating a negative effect(Garly and Aaby, 2003). Our results would support this, though it is important to keep in mind that RBP is a surrogate marker for vitamin A. The seemingly contradictory associations of measles antibody titer to the biomarkers could be due to the genetic component of measles vaccine response. There are high levels of heritability in vaccine response, with HLA alleles strongly affecting the humoral response (Jacobson and Poland, 2004). Underlying genetic control of measles antibody titer could cause interference in the analyses used in this study.

A child's growth in the first year of life was associated with biomarkers from each of the three clusters. EE and systemic inflammation biomarkers had negative associations with growth; this result indicates that localized enteric inflammatory damage and broad systemic inflammation both are likely to have an important effect on nutritional status. Maternal health was also identified as particularly important for tetanus vaccine response and child nutrition, with improved maternal health correlating with improved child growth. The SCAD analysis is of particular importance as the identification of biomarkers for vaccine response and nutrition representing enteric inflammation, systemic inflammation, and maternal nutrition, suggests three areas of potential intervention and monitoring.

This study had several limitations. Most importantly it was an observational study and therefore unable to demonstrate causality. Further, the study population was exclusively from a low-income urban slum where EE by our working definition was near universal. Comparison to healthy infants from a higher socioeconomic class in Dhaka could add to the understanding of EE impact on child health. The statistical analysis focused on linear relationships; it is possible that some of the biomarkers measured have a more complex relationship with the outcomes. Finally, the gold-standard tests for EE, the lactulose:mannitol ratio and biopsies, could not be used due to the very young age of our study cohort. However, combining the observations of previous research on EE with accepted tests for enteric inflammation, the study has broken significant new ground by developing a working definition of EE and demonstrating its importance in oral vaccine underperformance and failure.

5. Conclusions

EE was associated with Rotarix® failure and underperformance of OPV and predicted the development of malnutrition. Understanding the triggers of environmental enteropathy and designing interventions to prevent or treat it are therefore of immense importance. EE is uniquely seen in settings with high exposure to enteric pathogens, malnutrition and poor sanitation (Korpe and Petri, 2012, Prendergast and Kelly, 2012, Keusch et al., 2014, Guerrant et al., 2008). The absence of diarrhea on cluster 2 that contains the EE biomarkers leads us to postulate that asymptomatic enteric infection may contribute to environmental enteropathy. Infants in Dhaka, Bangladesh as young as one month have been found on average to have two enteric pathogens present in stool samples even without overt diarrhea (Taniuchi et al., 2013). It is possible that such subclinical infections could be causing a chronic innate immune activation localized to the gut. Within cluster 2 were also the sanitation markers reporting proximity to an open drain or the availability of a septic tank toilet; as for enteric inflammation biomarkers, it is interesting that these do not cluster with diarrheal burden. This clustering further supports the hypothesis that low-level exposure to pathogens drives enteric inflammation.

These results are of significance at the level of public health. Interventions focusing on EE, systemic inflammation, and improvement of maternal health could be predicted to make an impact on child health through improved oral vaccine response and nutrition. We have discovered that oral vaccine failure is likely the result of some of the same pathological processes that drive malnutrition, increasing the need for multifaceted interventions. The identification of systemic and enteric inflammatory clusters emphasizes the necessity of multi-pronged intervention strategies to EE to fully address malnutrition and oral vaccine failure. The use of noninvasive stool measurements to evaluate EE, as opposed to biopsy, also lends itself to application in future interventional studies: identification of biomarkers should make possible at-risk stratification and assessment of therapeutic response.

Oral vaccine failure and malnutrition affect more than one in four children worldwide, and are not adequately addressed by currently known interventions. This study, by better defining clusters of characteristics associated with malnutrition and vaccine failure, fills a knowledge gap to allow rational design and testing of interventions.

Author Contributions

CN wrote the paper and analyzed the data; ML and JM conducted the biomarker data analysis, RH co-designed the study and led the field site; DM, RC, MC, DD supported the field work; FK, WW and SO measured vaccine responses; EB measured biomarkers, BK co-designed the study and led the clinical site management; and WP led the study and edited the manuscript.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other contributing agencies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Raphael Gottardo for consultation on biostatistics, Alex Mentzer for assistance in measures of parenteral vaccine response, and the families of Mirpur for their participation in this study. This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and NIH grant 5R01 AI043596. The funders did not have any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.09.036.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplemental Table 1. Biomarkers measured between 6 and 18 weeks of age. The column of means and SE indicates values for the PROVIDE population.

Supplemental Table 2. Measurement of vaccine response.

References

- Black R.E., Allen L.H., Bhutta Z.A., Caulfield L.E., de Onis M., Ezzati M. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. (Jan 19) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D.I., Murch S.H., Elia M., Sullivan P.B., Sanyang M.S., Jobarteh B. Chronic T cell-mediated enteropathy in rural west African children: relationship with nutritional status and small bowel function. Pediatr. Res. 2003;54(3):306–311. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000076666.16021.5E. (Oct) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavent M, Kuentz V, Liquet B, Saracco J. ClustOfVar: an R package for the clustering of variables. J. Stat. Softw. 2011;50:1–16.

- Christiaensen L., Alderman H. Child malnutrition in Ethiopia: can maternal knowledge augment the role of income? Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2004;52(2):287–312. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cesare M., Bhatti Z., Soofi S.B., Fortunato L., Ezzati M., Bhutta Z.A. Geographical and socioeconomic inequalities in women and children's nutritional status in Pakistan in 2011: an analysis of data from a nationally representative survey. Lancet Glob. Health. 2015;3(4):e229–e239. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Salas P., Moore S.E., Baker M.S., Bergen A.W., Cox S.E., Dyer R.A. Nature Publishing Group; 2014. Maternal Nutrition at Conception Modulates DNA Methylation of Human Metastable Epialleles; p. 3746. (Nat Commun.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Li R. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. J. Am. Stat. 2001;96:1348–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Garly M.L., Aaby P. The challenge of improving the efficacy of measles vaccine. Acta Trop. 2003;85(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassly N.C., Fraser C., Wenger J., Deshpande J.M., Sutter R.W., Heymann D.L. New strategies for the elimination of polio from India. Science. 2006;314:1150–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1130388. (80-) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant R.L., Oriá R.B., Moore S.R., Oriá M.O.B., Lima A.A.M. Malnutrition as an enteric infectious disease with long-term effects on child development. Nutr. Rev. 2008;66(9):487–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00082.x. (Sep) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H.Q., Zhou X., Mitch W.E., Goldberg A.L. 45(10) Elsevier Ltd; 2013. Myostatin/Activin Pathway Antagonism: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Potential; pp. 2333–2347. (Int J Biochem Cell Biol). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque R., Snider C., Liu Y., Ma J.Z., Liu L., Nayak U. Oral polio vaccine response in breast fed infants with malnutrition and diarrhea. Vaccine. 2014;32(4):478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.056. (Elsevier Ltd, Jan 16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson R.M., Poland G.A. The genetic basis for measles vaccine failure. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2004;93(445):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb03055.x. (discussion 46–7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keusch G.T., Denno D.M., Black R.E., Duggan C., Guerrant R.L., Lavery J.V. Environmental enteric dysfunction: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical consequences. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;59 Suppl. 4(Suppl. 4):S207–S212. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu485. (Nov 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B.D., Colgate E.R., Mychaleckyj J.C., Haque R., Dickson D.M., Carmolli M.P. The “Performance of Rotavirus and Oral Polio Vaccines in Developing Countries” (PROVIDE) study: description of methods of an interventional study designed to explore complex biologic problems. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;92(4):744–751. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B.D., Haque R., Colgate R.E., Dickson D.M., Carmolli M.P., Mychaleckyj J.C. 2015. The Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination and Serum Zinc on the Burden of Rotavirus Diarrhoea in Bangladesh: A Randomised Controlled Trial. (submitted for publication) [Google Scholar]

- Korpe P.S., Petri W.A. Environmental enteropathy: critical implications of a poorly understood condition. Trends Mol. Med. 2012;18(6):328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.007. (Elsevier Ltd, Jun) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek M., Haque R., Lima A., Babji S., Shrestha S., Qureshi S. Fecal markers of intestinal inflammation and permeability associated with the subsequent acquisition of linear growth deficits in infants. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013;88(2):390–396. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0549. (Feb) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M.M. Developing countries : lessons from a live cholera vaccine. BMC Biol. 2010;8(129):2–11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay S., Gaudier E., Campbell D., Prentice A., Albers R. Environmental enteropathy: new targets for nutritional interventions. Int. Health. 2010;2(3):172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal D., Haque R., Sack R.B., Kirkpatrick B.D., WAP Short report: attribution of malnutrition to cause-specific diarrheal illness : evidence from a prospective study of preschool children in Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;80(5):824–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myaux J., Unicomb L., Besser R., Modlin J., Uzma A., Islam A. Effect of diarrhea on the humoral response to oral polio vaccination. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1996;15(3):204–209. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaltin E., Hill K., Subramanian S.V. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1507–1516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson K.M., Buss J., Easley R., Yang Z., Korpe P.S., Niu F. REG1B as a predictor of childhood stunting in Bangladesh and Peru 1–3. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;97(4):1129–1133. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.048306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast A., Kelly P. Enteropathies in the developing world: neglected effects on global health. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;86(5):756–763. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0743. (May) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S.A., Black R.E., Gilman R.H., Guerrant R.L., Kang G., Lanata C.F. Diarrhea in early childhood: short-term association with weight and long-term association with length. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013;178(7):1129–1138. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S.A., Black R.E., Gilman R.H., Guerrant R.L., Kang G., Rasmussen Z.A. Catch-up growth occurs after diarrhea in early childhood. J. Nutr. 2014;21:965–972. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.187161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniuchi M., Sobuz S.U., Begum S., Platts-Mills J.A., Liu J., Yang Z. Etiology of diarrhea in Bangladeshi infants in the first year of life analyzed using molecular methods. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208(11):1794–1802. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit507. (Dec 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organisation, the United Nations Children's Fund . 2009. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Knovich M.A., Coffman L.G., Torti F.M., Torti S.V. Vol. 1800. Elsevier B.V.; 2010. Serum Ferritin: Past, Present and Future; pp. 760–769. (Biochim. Biophys. Acta.). (Aug) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Cudd T.A., Meininger C.J., Spencer T.E. Maternal nutrition and fetal development. J. Nutr. 2004;13:2169–2172. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman K., Dang D., Victor J., Shin S., Yunus M., Dallas M. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in Asia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9741):615–623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Biomarkers measured between 6 and 18 weeks of age. The column of means and SE indicates values for the PROVIDE population.

Supplemental Table 2. Measurement of vaccine response.