Abstract

Although cross-sectional (between-person) comparisons consistently reveal age-related cognitive declines beginning in early adulthood, significant declines in longitudinal (within-person) comparisons are often not apparent until age 60 or later. These latter results have led to inferences that cognitive change does not begin until late middle age. However, because mean change reflects a mixture of maturational and experiential influences whose contributions could vary with age, it is important to examine other properties of change before reaching conclusions about the relation of age to cognitive change. The current study examined measures of stability, variability, and reliability of change, as well as correlations of changes in memory with changes in speed in 2,330 adults between 18 and 80 years of age. Despite substantial power to detect small effects, the absence of significant age differences in these properties suggests that cognitive change represents a qualitatively similar phenomenon across a large range of adulthood.

A considerable amount of data exists relating cognitive performance to adult age in nationally representative samples assessed with commercial cognitive test batteries (see Salthouse, 2010a for a review), in large convenience samples tested in the laboratory (e.g., Schaie, 2013; Ronnlund, et al., 2005), over the telephone (e.g., Lachman, et al., 2014), on the internet (e.g., Hampshire, et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2010; Logie & Maylor, 2009; Murre, et al., 2013; Sternberg et al., 2013), and with video games and personal electronic devices (e.g., Lee et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2014). Although there is often an increase in average performance until the age decades of the 60’s or 70’s for measures of general knowledge or vocabulary (Salthouse, 2014a), the dominant pattern with measures of efficiency or effectiveness of processing at the time of assessment is negative age relations starting when people are in their 20’s or 30’s.

The data in Figure 1 illustrate this phenomenon with results on a speeded substitution test from nationally representative samples used to establish the norms in different versions of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Note that the functions relating performance (in z-score units) to age are nearly parallel in the three time periods, with mean performance about .5 standard deviations above the sample mean for adults in their 20’s, and about 1.0 standard deviations below the sample mean for adults in their 70’s.

Figure 1.

Mean (and standard error) of sample Digit Symbol Coding test in nationally representative samples in three different time periods.

The age-cognition relations with cross-sectional data are quite consistent, but cross-sectional comparisons are sometimes considered misleading because assessments at different ages are based on different people who could vary in characteristics other than age that might affect their level of cognitive functioning. Because longitudinal studies are based on comparisons of the same people tested at different ages, they are often assumed to be more informative about age-related influences than cross-sectional studies. It is therefore noteworthy that although there are some reports of significant longitudinal declines among adults in their 40’s and 50’s, particularly for measures of speed (e.g., Anstey et al., 2014; Salthouse, 2011a; 2014b; Schaie, 1989; Singh-Manoux et al., 2012), significant within-person decline is typically not evident until adults are in their 60’s or later (Bielak et al., 2012; Giambra et al., 1995; Salthouse, 2010b; Schaie & Hertzog, 1983; Zelinski & Burnight, 1997).

Results such as these have been interpreted as indicating that little or no cognitive change occurs before about 60 years of age. However, the claim that cognitive change does not begin until the 60’s or later warrants careful examination because it has both theoretical and practical implications. For example, the search for causal factors contributing to cognitive decline could productively focus only on the period of middle or late adulthood if cognitive change does not occur until age 60 or later. Moreover, if cognitive change is exclusively a late-life phenomenon, efforts to distinguish normal and pathological trajectories, and interventions designed to minimize age-related declines, might safely ignore the periods of young and middle adulthood. However, both the search for causes and attempts to distinguish normal and pathological trajectories may be unproductive if the phenomenon of cognitive aging originated early in adulthood and adults in this age range are not included in the research.

Most of the prior research that has led to the conclusion that cognitive change begins in middle age or later has focused only on the mean value of change, and has not considered other important properties of change such as stability, variability, reliability, and correlations with changes in other cognitive abilities. This is unfortunate because, regardless of the relations of age with mean change, increased age might be associated with: (a) lower stability of scores if there is more across-occasion fluctuation in performance at older ages; (b) larger variability of change if there is greater divergence of the change trajectories at older ages; (c) higher reliability of change if a greater proportion of the variability in change is systematic at older ages; and (d) larger correlations of changes with one another if there is greater influence of a general factor of change at older ages.

Each of these characteristics is relevant to the issue of whether cognitive change represents the same phenomenon at different ages, but few systematic comparisons of their relations to age have been reported. To illustrate, although it is frequently assumed that individual differences in cognitive change are larger at older ages, only a limited number of comparisons of change variability at different ages have been published, and the results have been inconsistent. For example, Reynolds et al. (2002) reported greater change variance at older ages in some but not all cognitive measures, and little relation of age to change variability has been found in other studies (e.g., Finkel et al., 1998; Giambra, et al., 1995; Huppert & Whittington, 1993; Ronnlund & Nilsson, 2006). Furthermore, figures in Salthouse (2011a) and in Salthouse (2012a) revealed nearly constant standard deviations of change at different ages in cognitive measures from different data sets. A study by de Frias et al. (2007) is sometimes cited as having found age-related increases in change variance, but this may be misleading because the authors noted that “The majority of the variances were non-significant, which makes statistical comparisons across age groups redundant … [and] … interindividual differences in change tend to increase in old age, but could not be detected for the majority of the measures and age groups (p. 387)”.

Limited information is also available about age differences in the magnitude of correlations among changes in different cognitive abilities. In analyses of a subset of the current data, Tucker-Drob (2011) found no significant differences in the relations among changes in different cognitive domains. In another data set, Tucker-Drob et al. (2014) noted that correlations of changes in different cognitive variables were smaller for adults between 50 and 65 years of age compared to adults between 65 and 96 years of age, but direct statistical comparisons of the age differences in the correlations were not reported.

The goal of the current study was to examine properties of cognitive change in adults between 18 and 80 years of age who participated in the Virginia Cognitive Aging Project (VCAP) on at least two occasions. This project is ideally suited to investigate relations between age and cognitive change because it involved moderately large numbers of adults across a wide age range who have participated in at least two longitudinal occasions in which they performed multiple tests of several cognitive abilities. Key questions to be addressed were the relations of age with properties of cognitive change from a first to a second measurement occasion, including not only the mean value of change, but also stability, variability, reliability, and correlations with changes in other cognitive abilities. As noted above, each of these properties might be expected to exhibit significant age differences if cognitive change represents a qualitatively different phenomenon at different periods in adulthood.

Method

Sample

The current analyses are restricted to adults under 81 years of age at the first occasion to minimize influences of dementia and other late-life diseases that might affect cognition. Participants with Mini Mental State Exam (Folstein et al., 1975) scores less than 24 at either the first (T1) or second (T2) occasion were also excluded to reduce the impact of cognitive impairment on the results. In the primary analyses the individuals were grouped by 20-year age intervals to have sufficient power to detect possible age differences in relevant properties of change.

A unique feature of the VCAP study is a measurement-burst design, involving three sessions within a period of about two weeks at each occasion, during which the participants performed parallel versions of the primary tests. About half of the participants had complete scores on the second session of each occasion, which allowed correlations of the changes in the two sessions to be computed to estimate the reliability of change. Although intervals between the T1 and T2 measurement occasions varied across participants (see Salthouse, 2011c; 2014c), variability across intervals was ignored in the current analyses. However, nearly identical results were obtained when the analyses were repeated on data from participants in the middle 50% of the distribution of T1-T2 intervals. These individuals had a mean interval across occasions of 2.52 years and a standard deviation of 0.43, compared to the mean of 3.00 and standard deviation of 1.70 in the complete sample. Because the pattern of results among participants with a narrow range of intervals (i.e., from 2.0 to 3.2 years) was very similar to that in Table 2, interval variability can be inferred to have had little effect on the major findings.

Table 2.

Estimates of properties of latent change (with standard errors) and estimates of effect sizes.

| Age Group | Effect Sizes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y (18-39) | M (40-59) | O (60-80) | dY-O | dY-M | dM-O | |

| Mean Change | ||||||

| Memory | .13 (.02)* | .03 (.02) | −.09 (.02)* | −.45* | −.20* | −.26* |

| Speed | .06 (.02)* | −.02 (.01) | −.08 (.01)* | −.34* | −.19* | −.13* |

| Stability from T1 to T2 | ||||||

| Memory | .91* | .91* | .89* | .07 | −.02 | .09 |

| Speed | .94* | .89* | .91* | .02 | .05 | −.04 |

| Variance in Change | ||||||

| Memory | .09 (.02)* | .08 (.01)* | .09 (.01)* | .00 | −.03 | .03 |

| Speed | .04 (.02)* | .09 (.01)* | .06 (.01)* | .05 | .13* | −.11* |

| Reliability of Change (Correlation of change in session 1 with change in session 2) | ||||||

| Memory | .52* | .50* | .76* | .01 | −.06 | .07 |

| Speed | .82* | .60* | .68* | −.18* | −.04 | −.13* |

| Correlation Memory Change – Speed Change | .52* | .42* | .35* | −.04 | .01 | −.05 |

Note:

An in the age-group columns indicates that the value is significantly (p<.01) different from 0, and an * in the effect size columns indicates that the specified contrast was significantly (p<.01) different from 0 in an independent groups t-test.

Characteristics of the samples in the three age groups are reported in Table 1. Note that increased age was associated with slightly poorer self ratings of health, but with more years of education and higher estimated IQs.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants in three age groups.

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y (18-39) | M (40-59) | O (60-80) | Age r | |

| N | 475 | 1033 | 822 | NA |

| Age | 28.1 (6.7) | 50.8 (5.4) | 68.3 (5.8) | NA |

| Self-Rated Health | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | .08* |

| Education (years) | 14.8 (2.3) | 15.8 (2.6) | 16.3 (2.8) | .21* |

| T2 MMSE | 28.6 (1.6) | 28.7 (1.5) | 28.6 (1.5) | .00 |

| Est. IQ | 107.9 (13.7) | 111.5 (14.2) | 112.4 (12.8) | .09* |

| T1-T2 Interval (years) | 3.1 (2.0) | 3.1 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.4) | -.09* |

Note:

p<.01. Health is on a scale from 1 for “excellent” to 5 for “poor”. MMSE is the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein et al., 1975). Est. IQ was based on scores from three tests (Series Completion, Antonym Vocabulary, and Paper Folding) previously found to have a correlation of .93 with the Wechsler IV full scale IQ (Salthouse, 2014e). NA indicates that the value is not applicable.

Cognitive Measures

Only measures of memory and speed were examined in the current analyses because these were the only two abilities with significant change variance in each age group in an earlier report (Salthouse, 2014b). The memory measures consisted of the number of words recalled across four repetitions of the same list of 12 unrelated words, the number of response terms recalled across two lists of six unrelated stimulus-response word pairs, and the number of story units recalled across two stories, with two recall attempts for the second story. The speed measures all had fixed time limits, and consisted of the number of correct substitutions of a symbol for a digit according to a code table, the number of correct comparisons of line patterns, and the number of correct comparisons of sets of letters. Additional information about the measures, including reliability and validity (in the form of loadings of the measures on relevant ability factors), are contained in other publications (e.g., Salthouse, 2009; 2014b).

Individual test scores were converted to z-score units based on the test score mean and standard deviation on the first occasion. For some analyses, composite scores were formed by averaging the three z-scores for the relevant ability.

Analyses

Latent change models (McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994), with z-scores for the relevant tests serving as indicators of the cognitive ability constructs, were used to assess cognitive change. Details about the models used in the current study are provided in the appendix. Advantages of these models compared to other methods of assessing change are that they accommodate missing data with the full-information maximum likelihood algorithm, they simultaneously estimate level and change in performance, they minimize measurement error, they allow an evaluation of the fit of the model to the variance and covariance data, and they provide estimates of standard errors which can be used to derive effect sizes. With respect to this latter point, the standard error estimates can be converted to standard deviations by multiplying them by the square root of the sample size, and then effect size estimates (i.e., Cohen’s d) computed by dividing the difference between relevant parameter values by the pooled standard deviation. All of the latent change models had good fits to the data as the CFI values were greater than .96 and the RMSEA values were less than .07.

Results

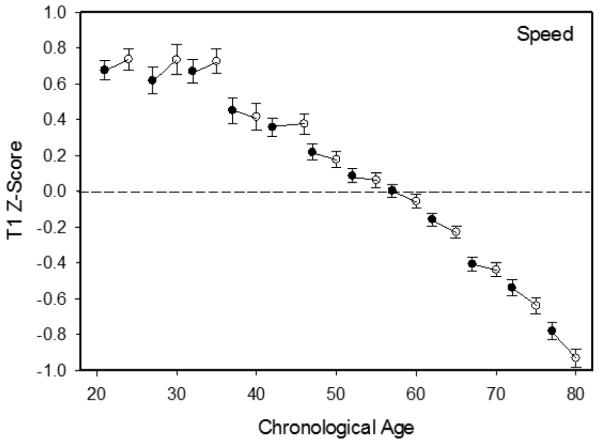

Composite scores from the first session on the T1 and T2 measurement occasions are portrayed by 5-year age groups in Figure 2 for memory, and in Figure 3 for speed. It can be seen that the change from the first to the second occasion was positive for participants younger than about 35 years of age, but that the change in both cognitive domains was negative at the oldest ages. Linear and quadratic relations of age were examined on the latent change estimates, and only the linear age trends were significant (p<.01).

Figure 2.

Mean (and standard error) of composite memory scores on the first session of the first occasion (filled circles) and the second occasion (open circles).

Figure 3.

Mean (and standard error) of composite speed scores on the first session of the fir occasion (filled circles) and the second occasion (open circles).

Because some of the relevant measures are group-based statistics (e.g., stability, reliability, variance), the sample was divided into three age groups for all remaining analyses. Results of analyses comparing properties of change obtained from the latent change analyses in the three age groups are presented in Table 2. In addition to the means and standard errors, the entries in the three columns on the right of the table contain estimates of effect sizes for the differences between pairs of age groups.

Mean change corresponds to the latent change estimate across the T1 and T2 measurement occasions. Consistent with the patterns in Figures 2 and 3, the changes were positive at young ages, but were progressively more negative with increased age. With both the memory and the speed measures the changes were significantly more negative at older ages in contrasts of the young and middle groups, and of the middle and old groups.

Stability of change was assessed by the correlation between the scores of the latent ability variables at T1 and T2. All of the stability coefficients were high, and there were no significant age differences in the size of the coefficients.

Individual differences in the magnitude (and direction) of change were represented by the estimated variance in change. The change variance estimates were all significantly greater than zero, indicating that there were significant individual differences in the amount of change in each age group. However, comparisons across age groups revealed similar change variance in the three age groups for memory, and a non-monotonic pattern for speed in which the middle group had significantly greater change variance than both the young and old groups.

As noted earlier, many of the participants performed alternate versions of the tests on a second session at each occasion. Reliability of change was therefore estimated from the correlation of change from the first session of T1 to the first session of T2 with the change from the second session of T1 to the second session of T2. Because only reliable variance among the indicators can be shared, the latent change estimates for a given set of data are not affected by measurement error. However, reliability of the estimates within a single data set does not necessarily imply high generalizability of the change estimates from that data set to another set of data. In fact, examination of the entries in Table 2 reveals that the correlations of the latent changes across the two sessions ranged from .50 to .82. There were no significant age differences in the reliability of memory change, but reliability of speed change was significantly higher in the young group than in than the middle and older groups.

Finally, correlations between change in memory and change in speed ranged from .35 to .52. There were no significant differences among the correlations, and small effect sizes for the differences between correlations, across the three age groups.

Discussion

The results in Figures 2 and 3 and in the first rows of Table 2 confirm prior reports of significant within-person decline in cognitive functioning only in adults 60 years and older. However, rather than abruptly declining at a particular age, the age-change relations were continuous throughout adulthood, with positive change at young ages, and gradually more negative change with increased age. Results from studies comparing performance of individuals of the same age who are tested for the first time when longitudinal participants are tested for the second time suggest that much of the positive cognitive change is likely attributable to effects of prior test experience in the longitudinal participants (e.g., Salthouse, 2009; 2014d; in press).

Despite significant declines in mean change only at older ages, the results with other properties of change suggest that the phenomenon of cognitive change in healthy adults is qualitatively similar between about 18 and 80 years of age. Lower stability across occasions and greater variance in change might have been expected at older ages if individual differences in rates of change were larger with increased age. A higher proportion of the change might have been expected to be reliable at older ages if the change was more systematic with increased age. And finally, stronger correlations of the changes in different abilities at older ages might have been expected if influences on change were more general, and less domain-specific, with increased age. Even though the samples in the current study were moderately large, which was associated with high power to detect small effect sizes (i.e., power of at least .8 to detect an effect size of .2 in a two-tailed test with alpha of .01), none of these expectations was supported.

The variance in change was significantly greater than zero in both the memory and speed measures in each age group, indicating that people differ in the amount (or direction) of cognitive change. These results are consistent with the widely held assumption that some people age more gradually than others in terms of cognitive functioning. However, the most relevant information from the current perspective is not the magnitude of change variability at any given age, but instead the relation between age and variability in change. In other words, the issue is not whether there is heterogeneity at any given age, but whether there is heteroscedasticity, with greater variance at some ages than others. The results in Table 2 indicate that differences among people in the estimates of change were not significantly larger among people in their 60’s and 70’s than among people in their 20’s and 30’s, or in their 40’s, and 50’s. There was a non-monotonic relation of change variance to age with the speed measures, but age differences in speed change variance were not significant in the analysis of data from participants in the middle 50% of the distribution of T1-T2 intervals, and thus this particular result may not be robust. There is therefore little evidence in these data that individual differences in cognitive change are greater at older ages, when the mean change is most negative. As noted in the introduction, little or no relation of age to variability in cognitive change has also been reported in other studies (e.g., Finkel et al., 1998; Giambra et al., 1995; Huppert & Whittington, 1993; Ronnlund & Nilsson, 2006).

The availability of measures from different versions of the same tests on the second session allowed reliability of change to be estimated from the correlations of the estimated changes in the two sessions. Reliability information is relevant to the qualitative nature of change at different ages because even if the total variance remained constant, increased age might be associated with a higher proportion of systematic (i.e., reliable) variance in change. However, this was not the case as the reliability estimates were largest in the young group for the measures of speed, and no significant differences were evident for memory.

Another similar property across age groups was the magnitude of correlations of memory change with speed change. As is evident in Table 2, there were no significant differences among the correlations, and thus there was no indication of an increase with age as one might expect if a general influence on change was becoming more powerful at older ages.

The findings reported here are consistent with those from earlier reports in which different, and in many cases less powerful, analytical procedures were used with subsets of the participants from the current data set. That is, little or no age differences have been reported in measures of across-occasion stability (i.e., Salthouse, 2010b; 2012a; 2014b), variance of change (i.e., Salthouse, 2010b; 2012a; 2014b), reliability of change (i.e., Salthouse, 2010b; 2012b), and in the correlations between change in different cognitive measures (Salthouse, 2010b; 2010c; 2012b; Soubelet & Salthouse, 2011). Furthermore, little or no age differences have been found in other properties of change, including effects of the length of the interval between measurement occasions on the magnitude of change (Salthouse, 2011b), effects of an intervening assessment on change (Salthouse, 2014c), the level at which change occurs in a hierarchical structure (Salthouse, 2012c); and in the magnitude of relations of change with other variables (i.e., Salthouse, 2010b; 2011a; 2012b; 2014b; Soubelet & Salthouse, 2011). When considered in combination, the results reported here and in a number of earlier studies strongly suggest that cognitive change has similar properties at different ages in adulthood.

At least two potential limitations of the study should be noted. First, it is possible that the lack of age differences in properties of change was attributable to the older adults in the current sample having more years of education, higher estimated IQs, or a shorter average longitudinal interval, than participants in the other age groups. Although factors such as these could be operating, their effects would be expected to be greatest on mean change, and the significant age differences in mean change suggests that their influences were likely small in this study. A second possible concern is that experiential effects on change could have been greater at younger ages, which may have contributed to the positive change at young ages and possibly inflated change variance compared to older ages when experiential influences on change might have been smaller. Unfortunately, rigorous evaluation of this interpretation requires separate estimates of experiential and maturational components of change in adults of different ages which are not yet available.

To summarize, even though significant negative change may not be detected until late middle age, the relations of cognitive change to age appear to be primarily linear, with no discrete shift when the decline is first significantly less than zero. Furthermore, the lack of age differences in other properties of change suggests that the processes operating in the 60’s and 70’s are qualitatively similar to those operating in the 20’s and 30’s. Taken together, these results are consistent with the idea that cognitive change represents the same phenomenon at different ages, and hence may involve similar mechanisms, and causes, throughout adulthood. Efforts to understand, and ultimately modify, both pathological and normal cognitive aging should therefore consider the entire range of adulthood, and not merely a segment in late life in which the mean declines are most pronounced.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R37AG024270. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

The latent change models were analyzed with the AMOS (Arbuckle, 2013) structural equation modeling program. Scores on the three tests representing the relevant ability (i.e., memory or speed), administered on each occasion were converted to z-score units based on the T1 means and standard deviations. These scores were then used to define occasion-specific latent ability variables with equal factor loadings, intercepts, and residual variances of the indicator variables on each occasion. The second occasion latent variable (LV2) was regressed, with a fixed regression weight of 1, on the first occasion latent variable (LV1) to create a residual latent variable representing across-occasion change (LVChange). Because the LV2 factor is defined as LV1 plus LVChange, rearrangement of the terms indicates that LVChange = LV2 – LV1. This formulation of longitudinal change not only yields an estimate of change without measurement error, but also provides estimates of the mean and variance of change, and standard errors of each parameter.

Interpretation of the results of latent change models is based on the assumption that the latent variables have the same meaning at each occasion. This assumption was investigated with the four-step procedure described in Widaman et al. (2010). Model 1 is a configural invariance model in which there were across-time correlations of the factors and of the residuals for each variable, but no constraints on the parameter estimates at each occasion. Model 2 was a weak factor invariance model that differed from Model 1 in that the factor loadings were constrained to be equal at each occasion. Model 3 was a strong factor invariance model that differed from Model 2 in that intercepts (means of the manifest variables) were also constrained to be equal across occasions. The final model, Model 4, was a strict factor invariance model that differed from Model 3 in that unique variances for the variables were also constrained to be equal at each occasion.

The difference in the chi-square test indicated significant loss of fit when progressively more constraints were imposed across successive models. However, the absolute fit was very good (i.e., comparative fit index [CFI] > .985, and root-mean-square error of approximation [RMSEA] < .064) for all models, including the strict factor invariance model incorporating all constraints. It was therefore concluded that the latent variables had very similar meaning in both measurement occasions.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anstey KJ, Sargent-Cox K, Garde E, Cherbuin N, Butterworth P. Cognitive development over 8 years in midlife and its association with cardiovascular risk factors. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:653–665. doi: 10.1037/neu0000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 22.0) [Computer Program] SPSS; Chicago: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bielak AAM, Anstey KJ, Christensen H, Windsor TD. Activity engagement is related to level, but not change in cognitive ability across adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:219–228. doi: 10.1037/a0024667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Frias CM, Lovden M, Lindenberger U, Nilsson L-G. Revisiting the dedifferentiation hypothesis with longitudinal multi-cohort data. Intelligence. 2007;35:381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer E, Salthouse TA, McArdle JJ, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. Multivariate modeling of age and retest in longitudinal studies of cognitive abilities. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:412–422. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel D, Pedersen NL, Plomin R, McClearn GE. Longitudinal and cross-sectional twin data on cognitive abilities in adulthood: The Swedish Adoption/Twin Study of Aging. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1400–1413. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giambra LM, Arenberg D, Zonderman AB, Kawas C, Costa PT. Adult life span changes in immediate visual memory and verbal intelligence. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:123–139. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A, Highfield RR, Parkin BL, Owen AM. Fractionating human intelligence. Neuron. 2012;76:1225–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert FA, Whittington JE. Changes in cognitive function in a population sample. In: Cox BD, Huppert FA, Whichelow MJ, editors. The Health and Lifestyle Survey: Seven Years On. Dartmouth; Aldershot, England: 1993. pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Logie RH, Brockmole JR. Working memory tasks differ in factor structure across age cohorts: Implications for dedifferentiation. Intelligence. 2010;38:513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Agrigoroaei S, Tun PA, Weaver SL. Monitoring cognitive functioning: Psychometric properties of the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone. Assessment. 2014;21:404–417. doi: 10.1177/1073191113508807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Baniqued PL, Cosman J, Mullen S, McAuley E, Severeson J, Kramer AF. Examining cognitive function across the lifespan using a mobile application. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28:1934–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Logie RH, Maylor EA. An internet study of prospective memory across adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:767–774. doi: 10.1037/a0015479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Using multivariate data to structure developmental change. In: Cohen SH, Reese HW, editors. Life-span developmental psychology: Methodological contributions. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 223–267. [Google Scholar]

- Murre JMJ, Janssen SMJ, Rouw R, Meeter M. The rise and fall of immediate and delayed memory for verbal and visuospatial information from late childhood to late adulthood. Acta Psychologica. 2013;142:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CA, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. Individual variation for cognitive decline: Quantitative models for describing patterns of change. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:271–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnlund M, Nilsson L-G. Adult life-span patterns in WAIS-R Block Design performance: Cross-sectional versus longitudinal age gradients and relations to demographic factors. Intelligence. 2006;34:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ronnlund M, Nyberg L, Backman L, Nilsson L-G. Stability, growth, and decline in adult life span development of declarative memory: Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:3–18. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiology of Aging. 2009;30:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Major Issues in Cognitive Aging. Oxford University Press; New York: 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The paradox of cognitive change. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010b;32:622–629. doi: 10.1080/13803390903401310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Does the meaning of neurocognitive change change with age? Neuropsychology. 2010c;24:273–278. doi: 10.1037/a0017284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Cognitive correlates of cross-sectional differences and longitudinal changes in trail making performance. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011a;33:242–248. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.509922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Neuroanatomical substrates of age-related cognitive decline. Psychological Bulletin. 2011b;137:753–784. doi: 10.1037/a0023262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Effects of age on time-dependent cognitive change. Psychological Science. 2011c;22:682–688. doi: 10.1177/0956797611404900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Are individual differences in rates of aging greater at older ages? Neurobiology of Aging. 2012a;33:2373–2381. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Robust cognitive change. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012b;18:749–756. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Does the level at which cognitive change occurs change with age? Psychological Science. 2012c;23:18–23. doi: 10.1177/0956797611421615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Quantity and structure of word knowledge across adulthood. Intelligence. 2014a;46:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Correlates of cognitive change. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014b;143:1026–1048. doi: 10.1037/a0034847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Frequent assessments may obscure cognitive decline. Psychological Assessment. 2014c;26:1063–1069. doi: 10.1037/pas0000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Why are there different age relations in cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons of cognitive functioning? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014d;23:252–256. doi: 10.1177/0963721414535212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Evaluating the correspondence of different cognitive batteries. Assessment. 2014e;21:131–142. doi: 10.1177/1073191113486690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Aging cognition unconfounded by prior test experience. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu063. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Perceptual speed in adulthood: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:443–453. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Developmental influences on adult intelligence: The Seattle Longitudinal Study. 2nd Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW, Hertzog C. Fourteen-year cohort-sequential analyses of adult intellectual development. Developmental Psychology. 1983;19:531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, Glymour MM, Elbaz A, Berr C, Ebemeier KP, Ferrie JE, Dugravot A. Timing of onset of cognitive decline: Results from Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubelet A, Salthouse TA. Correlates of level and change in the Mini-Mental Status Exam. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:811–818. doi: 10.1037/a0023401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg DA, Ballard K, Hardly JL, Katz B, Doraiswamy PM, Scanlon M. The largest human cognitive performance dataset reveals insights into the effects of lifestyle factors and aging. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00292. Article 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JJ, Blair MR, Henrey AJ. Over the hill at 24: Persistent age-related cognitive motor decline in reaction times in an ecologically valid video game task begins in early adulthood. PLOS One. 2014;9:e9425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Drob EM. Global and domain-specific changes in cognition throughout adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:331–343. doi: 10.1037/a0021361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Drob EM, Reynolds CA, Finkel D, Pedersen NL. Shared and unique genetic and environmental influences on aging-related changes in multiple cognitive abilities. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:152–166. doi: 10.1037/a0032468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Ferrer E, Conger RD. Factorial invariance within longitudinal structural equation models: Measuring the same construct across time. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski EM, Burnight KP. Sixteen-year longitudinal and time lag changes in memory and cognition in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:503–513. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]