Abstract

Thyroglobulin (Tg) is a vertebrate secretory protein synthesized in the thyrocyte endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it acquires N-linked glycosylation and conformational maturation (including formation of many disulfide bonds), leading to homodimerization. Its primary functions include iodide storage and thyroid hormonogenesis. Tg consists largely of repeating domains, and many tyrosyl residues in these domains become iodinated to form monoiodo- and diiodotyrosine, whereas only a small portion of Tg structure is dedicated to hormone formation. Interestingly, evolutionary ancestors, dependent upon thyroid hormone for development, synthesize thyroid hormones without the complete Tg protein architecture. Nevertheless, in all vertebrates, Tg follows a strict pattern of region I, II-III, and the cholinesterase-like (ChEL) domain. In vertebrates, Tg first undergoes intracellular transport through the secretory pathway, which requires the assistance of thyrocyte ER chaperones and oxidoreductases, as well as coordination of distinct regions of Tg, to achieve a native conformation. Curiously, regions II-III and ChEL behave as fully independent folding units that could function as successful secretory proteins by themselves. However, the large Tg region I (bearing the primary T4-forming site) is incompetent by itself for intracellular transport, requiring the downstream regions II-III and ChEL to complete its folding. A combination of nonsense mutations, frameshift mutations, splice site mutations, and missense mutations in Tg occurs spontaneously to cause congenital hypothyroidism and thyroidal ER stress. These Tg mutants are unable to achieve a native conformation within the ER, interfering with the efficiency of Tg maturation and export to the thyroid follicle lumen for iodide storage and hormonogenesis.

Introduction to Thyroglobulin and Its Role in Formation of Thyroid Hormones

The Tg Polypeptide and Thyroid Hormones in Evolution

-

Tg Primary Structure

Tg cysteine-rich repetitive units

The ChEL domain

Tg Iodination and Hormonogenesis

-

Tg Domain Foldability and Interdomain Interactions

Intramolecular chaperone and molecular courier functions

Dimerization function

The challenges of folding Tg region I

-

Chaperones and Oxidoreductases That Play a Role in Tg Maturation

The CRT/CNX cycle

Substrate recognition by CRT/CNX

Glycan-dependent oxidoreductase activity

Glycoprotein ERAD

Tg as a model substrate for CRT/CNX/ERp57 in secretory protein folding

Other oxidoreductases of the ER

Evidence of ER-oxidoreductase involvement in Tg folding

Alternatives Within the Tg Folding Pathway

-

Understanding Mutations Causing Congenital Hypothyroidism

Nonsense mutations and single nucleotide insertion/deletion

Acceptor and donor splice site mutations

Missense mutations

Conclusion

I. Introduction to Thyroglobulin and Its Role in Formation of Thyroid Hormones

The thyroid is the endocrine gland that synthesizes and secretes the thyroid hormones (THs) T3 and T4. Synthesis of T4, the primary form of TH released by the thyroid gland, consists of two sequential steps: iodination of selected tyrosines of thyroglobulin (Tg; a large glycoprotein), and coupling of two doubly iodinated tyrosines within Tg to produce T4. Thus, TH synthesis relies on iodide availability. Iodide abundance is not only limited in the terrestrial environment, but its intake is also variable, and this strikingly contrasts with the fact that TH is required continuously throughout human life. During fetal life and childhood, TH is critical for brain development, controlling myelination, somatogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and formation of neural processes, and the requirement continues in adult life as a regulator of intermediary metabolism (1). Thus, whereas insufficient iodide intake results in hypothyroidism and can promote goiter development in patients of all ages, in critical windows of development during fetal life and childhood it causes irremediable neurological manifestations.

To minimize the deleterious effects of iodide deficiency, a unique strategy for the structure of the thyroid gland evolved: specifically, iodinated TH precursor protein is stored extracellularly. This arrangement permits a massive storage that is even greater than the extensive intracellular storage capacity of the secretory granules of other endocrine cell types. Indeed, the anatomical unit of the thyroid follicle is the functional unit for TH synthesis within the mature thyroid gland. Thyroid follicles comprise a monolayer of polarized thyrocytes with the basolateral surface facing the bloodstream and the apical surface delimiting a central, spherical, follicle lumen (Figure 1). The lumen is filled with “colloid” (mainly highly concentrated Tg in different states of oligomerization) (2). Tg itself evolved under pressure to maximize iodide storage, as well as being an efficient molecular scaffold for TH synthesis, and the need to serve as the body's primary reservoir for iodide storage and TH synthesis amounts to two distinct evolutionary pressures that are simultaneously fulfilled by Tg within the thyroid follicular structure.

Figure 1.

TH synthesis and secretion. The thyroid gland is comprised of follicles and surrounding blood vessels. Follicles are the functional unit for TH synthesis and secretion. Thyroid follicles are a spherical monolayer of polarized thyrocytes with the basolateral surface facing the bloodstream and the apical surface delimiting a central follicle lumen. Iodine is taken up by thyrocytes by the action of the NIS exploiting the Na+ electrochemical gradient generated by the Na+/K+ ATPase. I− crosses the apical membrane and reaches the follicular lumen (I− efflux) by the action of the anion exchanger Pendrin and/or other transporters. I− is oxidized by TPO in the presence of H2O2 generated by the Duox2. Reactive iodide is covalently linked to selected tyrosyl residues of Tg to generate MIT and/or DIT. Under these oxidizing conditions, MIT and DIT are coupled to form THs T3 and T4. Newly synthesized Tg, TPO, and Duox2 are made in the ER and fold with the aid of general (CNX, CRT, etc) and dedicated (Duox maturation factor 2 for Duox2) chaperones before transport to the apical membrane. Newly secreted and iodinated Tg is endocytosed and degraded in lysosomes, and THs undergo transport to the bloodstream. The iodide from uncoupled MIT and DIT is recycled by tyrosine dehalogenase (Dehal1). Intact Tg is normally found in serum at low levels, but may exhibit increased concentrations in serum under conditions of increased thyroid cell mass (279), TSH stimulation (279), Graves' disease (280), subacute thyroiditis (281), and thyroid carcinoma. In the latter condition, post-thyroidectomy and ablation of residual thyroid tissue, serum Tg levels are used to monitor residual disease (282).

Remarkably, even when the huge extracellular colloid deposit is not considered, Tg is still the predominant protein of the thyroid gland. Tg has a monomeric molecular mass of approximately 330 kDa, and at approximately 2750 amino acid residues (after cleavage of the signal peptide), Tg falls in the largest 1% of proteins in the vertebrate proteome. The N-terminal two-thirds of the protein, known as Tg region I-II-III (3), contains multiple cysteine-rich repeat motifs, mainly the Tg type-1 domains (4), whereas the carboxyl-terminal region of Tg shows homology with the acetylcholinesterase (AChE; α-β hydrolase fold) superfamily (5) and is known as the cholinesterase-like (ChEL) domain. Roughly 10% of the molecular mass of Tg is carbohydrate, mostly N-linked oligosaccharides acquired as Tg (like other secretory and membrane glycoproteins) passes through the secretory pathway (6, 7). Tg possesses about 120 cysteine residues, and during its conformational maturation about 60 intramolecular disulfide bonds are formed (8). Thus, the achievement of the native three-dimensional structure of Tg is an elaborate and slow process (9, 10). Tg contains at least 66 tyrosine residues (in human Tg, and varying slightly between species). The percentage of tyrosine residues that become iodinated normally varies with dietary iodide intake, but under iodide-sufficient conditions, there may average 10–15 monoiodotyrosine (MIT) plus diiodotyrosine (DIT) residues, of which three or four may be recovered as TH (11, 12). At first glance, TH formation may appear as a wasteful process in which the thyrocyte must synthesize a protein of 330 kDa that can give rise to only three or four TH molecules. However, Tg is able to form THs at extremely low levels of iodination (even 4 mol of iodide per mole of Tg) (13), with the major TH-forming sites at the extreme N terminus (T4) and C terminus (T4 and T3), whereas other iodotyrosines constitute the body's primary reservoir of iodide for recycling within the thyroid gland (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cartoon view of Tg structure and function. Tg can be considered to have two main regions: the N-terminal, three-fourths are composed of cysteine-rich repeated motifs; and the carboxyl-terminal, one-fourth is composed of the ChEL domain. Thyroid hormonogenesis in Tg of most vertebrates favors T4 at a conserved site near the N terminus, T3 at a conserved site near the C terminus, and iodide storage via iodotyrosines located at various sites along the polypeptide chain.

II. The Tg Polypeptide and Thyroid Hormones in Evolution

The appearance of a molecular mechanism of TH synthesis based on Tg-like and thyroperoxidase (TPO)-like proteins appears to have preceded the evolution of the thyroid follicle. Indeed, TH synthesis occurs in the most basal nonvertebrate cephalochordates such as amphioxus and urochordates such as the sea squirt Ciona intestinalis (Figure 3). In these organisms, the endostyle (contained within the hypobranchial groove of the pharynx) accumulates iodide and synthesizes TH despite the absence of a thyroid follicular structure (14). In amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae), a large (still unidentified) protein that incorporates iodide via peroxidase activity (15) produces T3 and T4 (16). Recently, taking advantage of the complete amphioxus genome sequence (17, 18), orthologs of the main genes involved in TH synthesis and metabolism (sodium-iodide symporter [NIS], TPO, deiodinase enzymes) have been identified (19, 20). However, a typical Tg was not found, but many genes with homology to esterases or containing the Tg type-1 domain were noted. Among the latter predicted open reading frames is a protein of about 2400 amino acids (Bf_123169, estimated molecular mass of about 260 kDa), comprising numerous Tg type-1 domains (19). Thus, the hormonogenic function in an evolutionary ancestor of the Tg protein may have preceded the contiguity of N- and C-terminal regions found in modern vertebrate Tg. Moreover, these findings raise interesting questions as to whether the hormonogenic function associated with Tg appeared in evolution first in the region enriched in Tg type-1 repeat domains (the N-terminal region of modern vertebrate Tg) or in the ChEL-domain portion (the C-terminal region of modern vertebrate Tg). The answer to these questions may have to await cloning the TH precursor protein(s) of amphioxus and other nonvertebrate chordates. However, if the amphioxus TH precursor identified biochemically (16) does turn out to be the predicted 2400 residue protein (Bf_123169) (19), then this would imply that the capability to synthesize TH efficiently may have originated in proximity to Tg type-1 repeat domains.

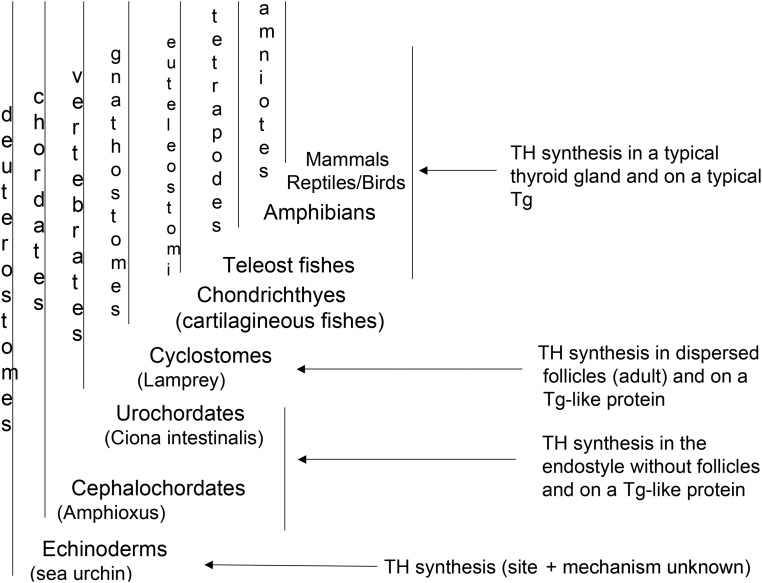

Figure 3.

Evolutionary progression of TH synthesis (from left to right). TH synthesis preceded the appearance of thyroid follicles or modern vertebrate Tg. In simple chordates such as the nonvertebrate amphioxus and Ciona intestinalis, TH synthesis occurs in the endostyle, an exocrine gland located in the pharyngeal region. Typical thyroid follicles can be recognized in the vertebrate lamprey, but only at the time of metamorphosis. In these simpler organisms, many orthologs of genes involved in TH synthesis have been identified, but not a complete modern-day vertebrate Tg—only various gene products containing Tg type-1 repeat domains or others homologous to ChEL. A complete modern-day vertebrate Tg is detectable in all teleost fishes and above.

In species even more primitive than chordates, THs are nevertheless important inducers of metamorphosis, such as in some echinoderms (sea urchins, sea biscuits, and sand dollars) (21–23). In such species, several proteins containing Tg type-1 repeat domains and others homologous to ChEL have been found (4). Moreover, peroxidase activity-dependent T4 production has also been demonstrated (24). In the sea urchin genome, as in amphioxus, many orthologs of genes involved in TH synthesis and metabolism—but not Tg—have been identified (19). Once again, these results point strongly to an origin of TH synthesis that precedes evolutionary development of the modern vertebrate Tg protein.

As above, in nonvertebrate chordates and in lamprey (and amphibians), TH signaling is also required for metamorphosis. In the parasitic lamprey, a simple vertebrate, the endostyle is present during the larval stage (ammocoetes), but after metamorphosis, a thyroid follicular organization develops (25). When iodoproteins from adult lamprey thyroid tissue (Petromyzon fluviatilis L.) were analyzed by velocity gradient centrifugation, the major component had a sedimentation coefficient of 12S and a molecular mass of 331 000 (26) and a larger 17–18S species; thus, the lamprey iodoprotein appears—features characteristic of the modern vertebrate Tg monomer although no typical Tg gene is yet described in publicly available genomes (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/downloads.html). Unfortunately, the low DNA coverage of publicly available genome sequences of cartilaginous fish (http://esharkgenome.imcb.a-star.edu.sg/) also does not yet reveal Tg (19), despite a follicular thyroid structure with extracellular colloidal protein that is highly likely to be enriched in stored THs (27) (Figure 4). From these analyses, it is still too early to say whether there is precise evolutionary coincidence of the follicular organization of the thyroid gland and a polypeptide exhibiting the typical structure of modern-day vertebrate Tg. However, the fact that vertebrate Tg is designed both for TH synthesis and iodide storage leaves open the possibility that these two functions might have derived from distinct gene products before the evolutionary need for iodide storage in sea creatures. Clearly, in teleost fishes and above, genetic rearrangements to include both Tg type-1 repeat domains and a contiguous carboxyl-terminal ChEL domain have already taken place.

Figure 4.

Thyroid morphology from thresher shark. This figure shows abundant extracellular colloidal protein, highly suggestive of Tg accumulation. [Reproduced from J. D. Borucinska and M. Tafur: Comparison of histological features, and description of histopathological lesions in thyroid glands from three species of free-ranging sharks from the northwestern Atlantic, the blue shark, Prionace glauca (L.), the shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrhinchus Rafinesque, and the thresher, Alopias vulpinus (Bonnaterre). J Fish Dis. 2009;32:785–793 (27), with permission. © John Wiley & Sons Ltd.]

III. Tg Primary Structure

The Tg gene structure, promoter region, splicing, and mRNA have been extensively described (28–33) and will not be reviewed again here. The primary structure of Tg was first deduced by reconstructing the predicted sequence from a series of overlapping bovine Tg cDNA clones (34). The encoded primary sequence of Tg (2749 amino acids in human Tg, after cleavage of the signal peptide) includes contiguous disulfide-rich regions I, II, and III (occupying the first ∼2170 residues) comprised of multiple repeat domains with cysteines at conserved positions, followed by the carboxyl-terminal ChEL region of approximately 520 residues. Beginning from the N terminus, the first 1200 residues of Tg are composed primarily of “Tg type-1 repeats” with an average size of roughly 60 amino acids, with three of the repeats bearing nonhomologous insertions as well as a “linker” between repeats 1–4 and 1–5, plus an approximately 235-residue “hinge” segment (all included within region I); three short type-2 repeats plus one additional type-1 repeat (altogether called region II); and finally, five type-3 repeats (about 520 residues, altogether called region III) (Figure 5). In sum, the first 2170 residues of Tg are described as regions I-II-III. The concluding ChEL domain contains only six of the many Cys residues of Tg.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the regional primary structure of Tg. The 270-kB homo sapiens Tgn gene (GenBank accession no. NT_008046 [older] or NG_015832 [current]) located on chromosome 8q24.2–8q24.3 (28–33) contains 48 exons separated by introns of varying sizes up to 64 kB, ultimately encoding an 8.5-kB mRNA (also see Figure 13). Within the encoded polypeptide shown in the figure, the various domains, insertions, and connecting sequences are not drawn to scale. The 11 Tg type-1 domains are in dark gray with four nonhomologous insertions designated as white vertical bars. The three type-2 repeats are in white, and five type-3 repeats are in light gray. The ChEL domain follows, and Tg concludes with a short stretch of nondomain sequence. The numbers above are approximate positions based on numbering the mature Tg peptide as position 1. The numbers below indicate the number of Cys residues in each domain, and numbers below the arrows specify Cys residues contained within linker and hinge and in a segment connecting type-2 and type-3 repeats.

A. Tg cysteine-rich repetitive units

1. Tg type-1 repeat: general structure and evolution

Tg type-1 repeats are classified as a domain superfamily recognized within the Structural Classification of Proteins database (35). The domain is notable for a central CWCV sequence and usually contains six cysteines in a conserved order (34). The Tg type-1 domain has been found as part of several functionally unrelated proteins. In the case of Tg itself, Tg type-1 repeats are subdivided into type-1A with six cysteines and type-1B with four cysteines (in the ninth and 11th repeats). Tg also contains an 11th type-1 repeat not contiguous with the others (residues 1492–1546) (36).

To begin to trace the evolution of the Tg type-1 domain, Novinec et al (4) collected a large dataset retrieved from GenBank or reconstructed from expressed sequence tag databases comprising genome sequences encoding 170 proteins containing 333 type-1 Tg domains. The Tg type-1 domains are specific modules that appeared early in the evolution of Metazoa, found mostly in extracellular proteins, and appear to be linked to the need to develop cell-cell or cell-matrix contacts. Many of the modern type-1 repeat-containing proteins appear to retain a function as a regulator of cysteine or cation-dependent protease activity (37, 38), and for some of them it has been shown that their inhibitory properties reside within the Tg type-1 domains (38–41)—including equistatin from sea anemone (40, 42), saxiphilin from bullfrog (38), and peptidase inhibitor from chum salmon egg (43).

Overall, in vertebrates, Tg type-1 repeats have been assembled into proteins organized in seven different modular architectures exemplified by: 1) testican; 2) secreted modular calcium binding protein (SMOC); 3) nidogens; 4) IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs); 5) major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-associated invariant chain; 6) Trop; and 7) Tg—with the last three being vertebrate-specific (Figure 6). These distinct architectures may allow type-1 domains to perform additional functions that are either superimposed or separated from the protease regulator function. As one example, human testican-1 (44) serves not only as a protease inhibitor but also as a substrate for certain cysteine cathepsin proteases (41). Early type-1 repeat-containing proteins evolved from their invertebrate homologs by incorporation of other vertebrate-specific domains. The oldest of the modular architectures, present throughout metazoans, are found in testican and the SMOCs, which are composed of Tg type-1 and SPARC-type extracellular calcium-binding (EC) domains with two different orders of presentation (EC-Tg type-1 in testican, Tg type-1-EC in SMOCs). Nidogen/entactin (a sulfated glycoprotein that is widely distributed in basement membranes and is tightly associated with laminin) (45) is already present in the urochordate Ciona intestinalis (together with IGFBP) and evolved by insertion of a Tg type-1 domain into a modular architecture composed of epidermal growth factor-like and nidogen domains. Three of the remaining four modular architectures (Trop, MHC class II-associated invariant chain, and Tg) appear to have been formed during vertebrate evolution (Figure 6). These unique modular architectures appear linked to specialized functions: the IGFBPs are involved IGF binding (46), the p41 splice variant of the MHC class II-associated invariant chain is involved in antigen processing (47), the Trops are involved in cell adhesion (48) and epithelial development (49), and of course Tg is involved in TH synthesis (50).

Figure 6.

Modular architecture of vertebrate Tg type-1 domain-containing proteins. The various domains and connecting sequences are not to scale. Tg type-1 domains are in gray, with other domains in white. AC, testican acidic region; CL, invariant chain class II-associated invariant chain peptide (CLIP) fragment; EC, SMOC, and Testican, extracellular calcium-binding domains; EGF, epidermal growth factor–like domain; FS, follistatin-like domain; G1, nidogen G1 domain; G2, nidogen G2 domain; IC, invariant chain intracellular domain; IGFBP, IGF binding protein domain; LY, low-density lipoprotein receptor-like YWTD repeat; SMOC, SMOC-unique domain; Tg1, Tg type-1 repeat; Tg2, Tg type-2 repeat; Tg3, Tg type-3 repeat; TM, transmembrane region; TST, testican-unique domain.

In teleost fishes, the Tg type-1 repeat domains can already be found to be organized in two clusters: an N-terminal cluster of four domains followed by a linker, with subsequent type-1 repeats thereafter. The N-terminal cluster of four domains may be linked to thyroid hormonogenesis—when the positions of iodinated tyrosyl residues are analyzed in teleost fishes, these map to iodination sites at Tyr-130 and Tyr-239 in the N-terminal cluster (51)—and certainly iodination at Tyr-130 has been suggested by several groups to be linked to T4 formation in mammals. Thus, there is a real possibility that at least a portion of thyroid hormonogenesis may be conserved within the N-terminal cluster of Tg type-1 repeat domains in all vertebrates. Many of the additional downstream iodination sites of Tg regions I-II-III of amniotes may have appeared as a consequence of the sea-to-land habitat change of tetrapods, favoring long-term iodide storage.

2. Sequence conservation and insertions in the Tg type-1 domains

Between different members of the Tg type-1 domain superfamily, there is high primary sequence variation. The residues that are most conserved include the central cysteine structure containing the CWCV motif and a Cys that tends to represent the final residue of each domain (36), plus Gly at positions 28 and 49, Gln at position 34, and Val at position 45 (Figure 7A). The relatively low number of conserved residues indicates the spectrum of Tg type-1 domain-containing protein variability (52).

Figure 7.

Targeting Tg type-1 domains 1–10 with protease sensitivity, glycosylation, and iodination: insertions in the basic domain. A, Tg domains are aligned according to Ref. 29. Conserved residues are indicated when present at least five times (in bold), with the exception of Y130 and Y685; otherwise they are generically indicated as X. Numbers within the sequence indicate the length of segments without similarities between domains. The four large insertions in domains 1.3 (two), 1.7, and 1.8, and the linker (248 residues between domains 1.4 and 1.5) appear to be regions of preferential proteolytic sensitivity, glycosylation, and iodination. B, Spacing between cysteine residues in proteins possessing type-1 domains. Disulfide linkages and spacing between the cysteines for GA733–2 and IGFBP-1,6 are from Refs. 54 and 53, respectively. In Tg, the spacings between linked cysteines in the basic domain common to GA733–2 and IGFBP-1,6 are variable as a result of four major (and some minor) insertions (see Figures 5 and 7A), whereas other spacings between adjacent disulfide linked pairs are highly conserved and equal to those of the GA733–2 and IGFBP-1,6.

The disulfide-bonding pattern of the Tg type-1 domain, although not determined experimentally in Tg, has been determined in IGFBP-6 and GA733-2 (53, 54), producing covalent bonds in the order Cys1-Cys2, Cys3-Cys4, and Cys5-Cys6. In Tg are four major sequences of variable length, unrelated to the repetitive unit but inserted into repeats 1–3, 1–7, and 1–8 (Figure 5). As a result of these insertions, the spacings between presumptive disulfide partners in some of these repeat domains are quite variable, including between Cys3-Cys4 (in repeats 1–3 and 1–7), Cys5-Cys6 (in repeat 1–3), and Cys1-Cys2 (in repeat 1–8). By contrast, Tg type-1 domains across other proteins (IGFBP-1 and -6 [Ref. 53], and GA733–2 [Ref. 54]) do not show such variations (Figure 7B).

In addition to the four inserted sequences are the linker region that falls cleanly between Tg repeats 1–4 and 1–5 (55) and the hinge region that follows immediately after Tg repeat 1–10 (56). The linker region is likely to be important for the ultimate proteolytic cleavage of Tg (see Section III.A.4), whereas the novel hinge region is likely to be critical to overall Tg folding (55).

3. Origin of type-1 insertions, linker, and hinge regions

Parma et al (29) sequenced the exon/intron junctions of the first 16 exons of the Tg gene, corresponding to the 10 Tg type-1 domains, and compared them with the protein sequence. There is often a correlation of “one exon-one domain” within modular proteins (57). Indeed, Tg repeat domains 1–2, 1–4, 1–7, and 1–10 are each encoded by a single exon, and domain 1–5 together with 1–6 is encoded by one exon. To the contrary, domains 1–1, 1–3, and 1–9 are interrupted by one intron, and domain 1–8 is interrupted by two introns. Of these “intradomain” interruptions, introns 5, 6, and 11 are located near the borders of the novel inserted sequences, intron 8 is near the border of the linker, and other introns appear to separate natural disulfide-linked cysteine partners (Figure 7A). This suggests the possibility that during evolution, there may have been exonization of previous intronic sequences to create the novel insertions (29).

4. Functional roles of the type-1 insertions, linker, and hinge regions

Preservation of possible exonization events during evolutionary development of the vertebrates suggests that they may provide selective advantage. The actual fold of the Tg type-1 domain has been resolved in the crystal structure of the p41 fragment–cathepsin L complex (52), and more recently, in solution, for the isolated p41 fragment (58) and the C-terminal part of IGFBP-6 (46). When the two conformations are superimposed, the three disulfide bonds create three loops, with the first containing an α-helix in its N-terminal part and the second connecting an antiparallel β-sheet, but the IGFBP-6 domain exhibits prolongation of the N-terminal α-helix and elaboration of the second loop because of insertions in these positions (Figure 8). As noted above, several type-1 domains within Tg contain insertions falling between disulfide-linked cysteines, plus there is the presence of the linker region between type 1–4 and type 1–5 repeats (Figure 7A). These features are also likely to extend loops within Tg region I (to a greater extent than in IGFBP-6) as well as to present unique peptide sequence for post-translational modifications and proteolytic cleavage (Table 1). Interestingly, except for the proximal linker region, these additional peptide sequences lack Cys residues (Table 1), indicating that they have high flexibility rather than participating in covalent scaffolding of the protein.

Figure 8.

The fold of Tg type-1 domain. Superimposition of three-dimensional structures of the Tg type-1 domain of IGFBP-6 (light gray) (46) and p41 fragment (dark gray) (58). The three disulfide bonds (shown as sticks) determine three loops, with the first containing an α-helix in its N-terminal part, and the second connecting an antiparallel β-sheet held in place by the second disulfide bond. Between various members of the family bearing this domain, including Tg itself, the domain structure tends to differ in the elaboration of sequences within loop I and loop II.

Table 1.

Features of Tg Type-1 Repeat Domains

| Repeat | C-C | aa | Cysteine Residues | Protease Sensitivity |

Glycosylation |

Iodination |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Bovine | Human | Bovine | Human | Mouse | ||||

| Large insertions and linker | |||||||||

| 1.3 | C3-C4 | 40 | No | 179 | |||||

| 1.3 | C5-C6 | 43 | No | 240 | 239 | 239don | |||

| Linker | 248 | 2 | Cluster A | Cluster A | 465 | 464 | 363 | ||

| 532* | 510 | 476 | 410 | ||||||

| 551* | |||||||||

| 1.7 | C3-C4 | 123 | No | 795* | 797 | 834 | 766 | 765 | |

| 847don | |||||||||

| 864 | |||||||||

| 1.8 | C1-C2 | 99 | No | Cluster B | Cluster B | 928 | 926 | 973 | 973acc |

| Small insertions | |||||||||

| 1.2 | C1-C2 | 18 | No | 91 | |||||

| 1.5 | C1-C2 | 6 | No | 597 | |||||

| 1.7 | C1-C2 | 27 | No | 729 | |||||

| 1.10 | C1-C2 | 14 | No | 1142 | |||||

| 1.10 | C5-C6 | 3 | No | 1184 | |||||

| Outside insertions | 57 | 1121 | 130don | 130 | |||||

| 685acc | 672 | ||||||||

| 684 | |||||||||

| 1095 | |||||||||

Abbreviations: C-C, the pair of disulfide-linked cysteines in a given Tg type-1 repeat; a-a, number of amino acids inserted in the corresponding pair of disulfide-linked cysteines; acc, TH acceptor site; don, TH donor site. Cysteine residues indicates the number of cysteine residues by inspection of the sequence of human Tg (van de Graaf et al, 2001 [33]). Protease sensitivity sites, glycosylation sites, and iodinated tyrosines primarily cluster in the four major insertions and linker region of the Tg type-1 domains, secondarily in the small insertions, suggesting that they represent solvent-exposed segments available for modifications and cleavage.

Cathepsins.

When sites of proteolytic cleavage of human, bovine, and rat Tg were analyzed, four major clusters of cleavage sites were identified: cluster A falls around residue 500 in the linker region, cluster B is around residue 990 in an inserted sequence within the type 1–8 repeat, cluster C is located near residue 1800 (within the type-3 repeats), and cluster D is around residue 2515 (in the ChEL domain). Dunn et al (59) analyzed the sensitivity of Tg to cathepsins—the enzymes that initially hydrolyze Tg upon endocytosis to liberate TH—and described primary cleavage sites in these clusters, which are thought to enhance liberation of TH. Additional cleavages have been found to occur in the insertion within domain 1–3 (position 240; Figure 7A and Table 1), in small insertions in domain 1–10 of bovine Tg (positions 1142 and 1184; Figure 7A and Table 1), and in the small insertion in domain 1–5 of human Tg (position 597; Figure 7A and Table 1) (60). Thus, of those cleavage sites that reside within the Tg type-1 domains, all are located within disulfide loops or in the linker region, suggesting that these segments “present themselves” to proteases for processing. Moreover, when the locations of actual glycosylation sites have been analyzed, all but one (residue 57) fall in these loops or in the linker region of human Tg (61), and the same pattern is observed in bovine Tg (Figure 7A and Table 1). Altogether, these data strongly suggest that the insertion and linker regions represent solvent-exposed segments available for modifications and cleavage (59, 62, 63).

Because Tg is the molecular scaffold for TH synthesis and iodide storage, it is worthwhile to note the location of iodination sites within Tg type-1 domains. Of the 7–9 Tg type-1 tyrosines that have been found to be iodinated (51, 64) 55–70% are present in insertion and linker segments, with most being involved in iodide storage rather than hormonogenesis. Thus, we hypothesize that the insertions and linker segments have been preserved because of their evolutionary advantage in long-term iodide storage (which occurred upon sea-to-land migration of vertebrates), whereas the flexibility of these loops may not be optimal to meet the rigid structural requirements needed for iodotyrosine coupling for hormonogenesis.

5. Tg type-2 and -3 repeats

The middle part of Tg is constituted of three type-2 repeats, each of 14 to 17 residues, two of which are cysteines that are distant members of the GCC2/GCC3 domain superfamily (65). Additionally, there are five type-3 repeats, subdivided into 3a with eight cysteines each and 3b with six cysteines each, alternating with each other, and which exhibit only internal homology. Similar to the Tg type-1 repeats, it is thought that the Cys residues of type-2 and type-3 repeats are all consumed in internal disulfide bonds (34).

B. The ChEL domain

The carboxyl-terminal ChEL domain of Tg (about 520 amino acids) shows homology with the AChE (66) and other esterases (5). These enzymes belong to the class of α-β hydrolase fold superfamily, characterized by α–helices and β-strands that roughly alternate along the polypeptide chain (67). The crystal structure of several members of this superfamily has been solved; they are characterized by a common core: an α/β sheet of eight β-strands connected by α-helices (68, 69) (Figure 9, boxed). AChE, the prototype from this superfamily (70), is a homodimer held together by a four-helix bundle composed of helices α-7/8 and α-10 from each subunit (where 7/8 indicates the loop connecting β-strands 7 and 8, and 10 indicates the C-terminal segment following β-strand 10) (71–73). The four-helix bundle may be further stabilized by a interchain disulfide involving the C-terminal C536, but this is not required for homodimerization (74).

Figure 9.

The Cholinesterase family fold. The ChEL domain of Tg shows homology with members of the α-β hydrolase fold superfamily (68, 69) including AChE (66, 70), whose structure is shown. Like ChEL, AChE forms a homodimer held together by a four-helix bundle composed of helices α-7/8 and α-10 from each subunit (gray cylindrical segments) (71–73).

A comparison of the known three-dimensional structures of AChE and a neuroligin (a related ChEL protein) (75, 76) with that predicted for ChEL by ESyPred3D (77) supports a shared overall protein architecture between these AChE paralogs (78). Notably, all six Cys residues involved in AChE intrachain disulfide pairing are conserved in Tg, suggesting that they form the same intradomain disulfide bonds (79). However, whereas some members of the superfamily have enzymatic activity that depends upon a catalytic triad of three amino acids (Ser, Glu/Asp, and His) (80) (Figure 9) positioned in a β-sheet platform at the bottom of a narrow and deep gorge (81), the ChEL domain of Tg lacks the Ser residue of the catalytic triad as well as conserved flanking residues (Table 2) such that it does not encode an active esterase (82). Thus, the Tg ChEL domain has diverged away from catalytic functions in favor of a critical role in three-dimensional protein assembly (see Section V) as well as in TH synthesis.

Table 2.

Absence of the Esterase Catalytic Triad in Tg

| 200 | 326 | 440 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torpedo | AChE | VTLFGE S AGGASV | NKD E GSFF | GVI H GY |

| Bovine | AChE | VTLFGE S AGAASV | AKD E GSYF | GVP H GY |

| Human | AChE | VTLFGE S AGAASV | VKD E GSYF | GVI H GY |

| Rat | Tg | VTLAAD R GGADVA | SQD D GLIN | G– H GS |

| Mouse | Tg | VTLAAD R SGADVA | SQD D GLIN | G– H GS |

| Bovine | Tg | VTLAAD R GGADIA | SQD D GLIN | S– H SS |

| 2368 | 2496 | 2601 |

Numbering is provided for the critical residues of Torpedo AChE (above) as well as for bovine Tg (below). Note that Tg in all species lacks the critical Ser residue of the catalytic triad of AChE.

IV. Tg Iodination and Hormonogenesis

The most specific post-translational modification of Tg is iodination leading to T4 and T3 synthesis. Indeed, through the combined actions of the NIS, dual-function oxidase (Duox), and TPO, iodide becomes covalently linked to tyrosyl residues on Tg to form MIT or DIT. Selected pairs of DIT residues serve as functional hormonogenic units; a coupling reaction permits a donor DIT to contribute its iodophenyl group via a quinol-ether linkage to a DIT acceptor that serves as the site of T4 formation. Analogous coupling of an MIT donor with a DIT acceptor leads to de novo formation of T3. (Coupling of noniodinated tyrosine donor with a DIT acceptor could result in formation of 3,5-T2, which is not an active TH.) Both T4 and T3 are formed while still residing within the Tg polypeptide backbone (83). Release of the iodophenyl moiety at the donor site during the coupling reaction leaves a dehydroalanine that also resides within Tg, and this is converted to pyruvic acid upon cleavage of the polypeptide chain (84–88). Interestingly, when Tg is iodinated (even nonenzymatically) in vitro, it leads to similar levels of iodide incorporation as well as TH synthesis (86), indicating that hormone formation is encoded primarily within the structure of the Tg substrate rather than via specificity of the TPO enzyme.

The three-dimensional structure of Tg is designed for efficient TH formation within the Tg molecule. Iodinated Tg yields much more T4 and T3 than iodination of other proteins, whereas denatured Tg is an incompetent substrate for hormonogenesis (89). Indeed, even limited structural modifications decrease the efficiency of hormone formation (90). The initial iodination of Tg tyrosyl residues tends to occur at preferred sites and in a preferred order (91). After incorporation of the first few iodide atoms into Tg, formation of DIT becomes favored over the formation of additional MIT residues (92), increasing the chances for hormone formation. Moreover, because DIT becomes deprotonated with a pKa of 6.5 (whereas MIT has a pKa around 8.5), physiological pH favors DIT as an acceptor site in the coupling reaction, creating the hormonogenic inner ring of T4 and T3 (93). In vivo, T4 is formed in Tg from human goiters even at 4 mol of iodide per mole of Tg (13). Thus, the tyrosine residues that are iodinated first are preferentially used for hormone formation, whereas preferential synthesis of T4 is not observed upon iodination of other proteins such as casein or fibrinogen or upon iodination of denatured Tg (94). At an average level of iodination, out of 134 tyrosyl residues per human Tg dimer, only 25–30 are iodinated, and only six to eight of these form iodothyronines (11, 12). Tyrosine 5 is the most efficient T4-forming residue in most species, and in rat Tg this has been shown to be the first tyrosine residue to become iodinated (95). In short, Tg encodes a “hierarchy of tyrosyl residues” that preferentially are mono-iodinated, di-iodinated, and coupled to form THs using donor and acceptor sites at specific positions in the three-dimensional Tg protein structure.

The identification of these sites has been performed by limited proteolysis of Tg followed by sequencing or mass spectrometry of peptides to find iodotyrosines, iodothyronines (acceptor sites), and dehydroalanine or pyruvic acid (donor sites). As reviewed elsewhere (33), four main hormonogenic acceptor DIT residues have been identified in Tg from several animal species, including position 5 (“site A”), 2554 (“site B”), 2747 (“site C”), and 1291 (“site D”). (These sites correspond to most reports in which Tg numbering begins with the first residue after signal peptide cleavage.) Other minor acceptor sites include 2568, 685, and 632 (not present in human Tg). As noted above, Tyr-5 is the most favored site for T4 formation (Tyr-2554 is second most efficient for T4 formation), whereas Tyr-2747 is the preferential site of T3 formation (51, 96). It has been noted that T3 is specifically increased within the Tg protein of patients with Graves' disease and iodide deficiency (11, 97).

One explanation for a relative increase of T3 synthesis in Tg at low iodine intake may be a higher MIT/DIT molar ratio at low levels of Tg iodination (12, 13, 98). In rabbit Tg, at an average level of iodination, the two major T4-forming sites (Tyr-5 and Tyr-2554) can be found to contain both T4 and T3, with a prevalence of T4 (96), indicating that donor tyrosines are fractionally distributed between a majority of DIT and a minority of MIT. Interestingly, in human Tg, the iodination status of the acceptor Tyr-5 is relatively insensitive to the level of iodination, being mostly DIT under all conditions (51), whereas the major T4 donor site (Tyr-130) shows a 1.57-fold increase in MIT/DIT ratio under low iodine conditions (51), which could increase the relative synthesis of T3. However, in Graves' patients, Tg also shows a higher T3 content that cannot be explained by diminished iodination (11). It has been reported that TSH increases the T3/T4 ratio in Tg by directly enhancing T3 synthesis (99). TSH receptor activation might enhance monoiodination of donor tyrosines or might even change donor iodotyrosines to different MIT residues, which would clearly imply structural changes in the Tg synthesized under high TSH conditions. Because TSH has known structural effects on Tg (eg, altered glycosylation) (100), the possibility exists that enhancement of T3 formation is the indirect result of TSH receptor activation affecting earlier post-translational modifications that subtly change Tg structure, which may occur in iodine deficiency as well as in Graves' disease (because both have TSH receptor stimulation). (As a caveat, it must be noted that the T3/T4 ratio embedded within the Tg protein can be further increased in thyroid secretion [Ref. 101] as a result of cytosolic T4 to T3 deiodination by thyroid-expressed iodothyronine deiodinases type-1 [D1] and type-2 [D2]) (102, 103). Indeed, increased TSH receptor activation in Graves' patients may lead to increased D1 mRNA and enzyme activity (104–106). However, because Tg itself is never free in the cytosol, to the best of our knowledge, Tg itself does not serve as a substrate for these deiodinases.

Several donor DIT or MIT residues have been described, including at positions 5, 926, 986 or 1008, and 1375 of bovine Tg (88); 2469 and/or 2522 of calf Tg (107); and 130, 847, and 1448 of human Tg (51).

Recently, using a shotgun-based mass spectrometry approach, the iodination sites have been directly analyzed on mouse Tg without purification, which may avoid inherent bias (64). In this case, 36 iodinated tyrosines, four hormonogenic sites, and two donor sites were identified. In the mouse Tg protein sequence, homonogenic sites were reported at positions 5 (T4 only), 973 (T3 only, and this position had not previously been reported as a hormonogenic site), and 1290 and 2552 (both T3 and T4). Dedieu et al (64) did not detect any dehydroalanine (donors) in mouse Tg, but they did detect pyruvic acid (donors) with peptide bond cleavage at Tyr-239 (a previously unreported donor site) and Tyr-2519 (which corresponds to the donor site identified in calf Tg at position 2522) (107). However, in these types of studies, the identified donors will not be matched with particular acceptors until we learn which donor-acceptor couples are brought into close proximity within the three-dimensional structure of Tg and in an orientation that permits formation of a charge transfer complex between the partners (108). As noted above, Tg polypeptide is comprised of four regions bearing intra-domain and intra-regional disulfide bonds; thus, it seems likely that the folding domains of Tg may coincide with at least some if not all of the hormone-forming sites because many donor-acceptor iodotyrosine pairs are localized in the same region of individual Tg monomers. With this in mind, it is not surprising that DIT at position 130 is a donor to DIT at position 5 for T4 formation (84, 109)—representing one of the most prominent early iodination sites of Tg. Position 1375 was suggested to be a donor for position 1291, both being in the middle part of Tg (87). Analogously, a segment comprising the 224 C-terminal amino acids of rat Tg was reported to be capable of hormone formation (110), suggesting that donor(s) site(s) may also be contained in this fragment (although they are neither positions 2469 nor 2522 reported in calf Tg [Ref. 107]—corresponding to positions 2468 and 2521 of rat Tg—because these residues are not contained within the 224 residue C-terminal fragment).

Besides the information encoded by the three-dimensional organization of Tg, the residues in the local environment flanking the iodination sites may also favor iodination and/or coupling. In vitro iodination of human Tg reveals three “consensus sequences” that, according to the prevailing view, favor iodination and coupling (50): Asp/Glu-Tyr, Ser/Thr-Tyr-Ser, and Glu-X-Tyr. The two major T4-forming sites at positions 5 and 2554 have the sequence Glu-Tyr and Asp-Tyr, respectively (51). The sequence Asp-Tyr is also found at minor hormone forming sites including 1291, 2568, and 973 in human Tg (and the corresponding positions in other species) (96). However, in human Tg, the Asp/Glu-Tyr “consensus sequence” is also found at four other sites that have not been reported to be iodinated. In mouse Tg, Dedieu et al (64) found Asp/Glu-Tyr at eight positions with hormone formation at positions 5, 2552, 1290, and 973 (position 5 carried only T4 and position 973 carried only T3), plus iodination without hormone formation at four remaining positions. Thus, in both humans and mice, the Asp/Glu-Tyr sequence appears associated with acceptor tyrosyl residues, although not all Asp/Glu-Tyr sites are associated with hormone formation.

The Ser/Thr-Tyr-Ser “consensus sequence” is associated with T3 synthesis at the carboxyl terminus of Tg in many species, including human, mouse, calf, guinea pig, and rabbit (50). In human Tg, the Ser/Thr-Tyr-Ser sequence also surrounds positions 864 and 1448, sites that have been found to be iodinated without hormone formation (51); but in mouse Tg, this sequence is present only at the carboxyl-terminal T3-forming site (and it has not yet been possible to determine whether this is invariably associated with T3 formation or also with T4 formation).

The Glu-X-Tyr “consensus sequence” appears to favor iodination over hormone formation. In human Tg, this sequence occurs seven times; all the tyrosyl residues are iodinated, with only one being a minor acceptor (at position 685), although two are potential donor sites (at positions 130 and 847) (51). In the mouse, six of eight such occurrences were found to be associated with iodination rather than hormone formation (64), and again, two potential donor sites were identified (at positions 130 and 239). On the basis of these results in both mice and humans, it appears that Glu-X-Tyr is most favorable for iodination, whereas the Asp/Glu-Tyr sequence does indeed tend to favor acceptor-site function in the hormonogenic coupling reaction. More work is still clearly needed to understand fully the chemical mechanism underlying the donor-acceptor pairing.

To liberate T4-forming as well as T3-forming sites from Tg, cathepsin proteases are likely to be involved (59). Upon incubation of endopeptidase-rich lysosomal extracts with in vivo-labeled Tg, it was shown that initial cleavages involve the liberation of hormone-containing iodopeptides that precede the release of free TH, and cathepsins B and L (more than cathepsin D) are important in this process (111). More recently, the presence in thyroid of cathepsins K (112) and S (113) has also been demonstrated. Early cathepsin-mediated proteolytic processing begins with attack near the major hormonogenic sites at both ends of the Tg molecule, resulting in a slightly smaller-than-normal dimeric Tg with diminished TH content, removed by limited proteolysis (114). Although cathepsins reside mostly in endo-lysosomes (59, 111), minor amounts of all cathepsins can be detected in the follicular lumen (113) and may be functional within the extracellular environment (115, 116). In the follicular lumen, especially in conjunction with iodination, higher-order oligomers of Tg are formed (2) via disulfide bonds (117) and dityrosine bridges (118). Such iodine-rich, multimeric Tg is not enriched in TH (119) possibly because hormone-rich iodopeptides have already been released by limited proteolysis. Indeed, follicular Tg analyzed under reducing conditions gives rise to multiple iodinated fragments, including several fragments that contain the main N-terminal hormonogenic site (120). These findings suggest the hypothesis that secreted cathepsins may be responsible for initial processing of follicular Tg, including the higher-order covalently-linked oligomers (112, 113, 117, 118)—although it must be noted that peptide bond cleavage may also occur during the oxidative process of iodination itself (121).

V. Tg Domain Foldability and Interdomain Interactions

A. Intramolecular chaperone and molecular courier functions

Because iodination and coupling reactions are catalyzed at the apical surface of the thyrocyte, Tg must be transported along the secretory pathway as a prerequisite for thyroid hormonogenesis. Interestingly, rather than causing defects in its ability to synthesize TH per se, most Tg mutations responsible for congenital hypothyroidism (see Section VIII) cause folding defects that result in a failure of Tg intracellular transport to the site of iodination. Tg folding engages assistance from multiple endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones and oxidoreductases, but also requires internal regional interactions within Tg.

When Tg region I-II-III is expressed separately from ChEL (stop codon at position 2169) and ChEL is also expressed in isolation (by introducing an artificial N-terminal signal peptide), ChEL is rapidly folded and secreted, whereas region I-II-III remains incompletely folded and trapped within the ER (3) (Figure 10A). By contrast, simultaneous coexpression of the secretory ChEL with Tg region I-II-III rescues oxidative folding, stability, and secretion of this latter (Figure 10B), and the two separate proteins (I-II-III and ChEL) remain associated even after their secretion (3). Intriguingly, when an artificial N-terminal signal peptide is positioned at the 5′ end of II-III, this polypeptide also folds easily in the ER and is rapidly secreted (56) (Figure 10A). Thus, it seems likely that the intramolecular rescue by ChEL is directed mostly toward the improved folding stability of Tg region I. Curiously, other members of the family of ChEL proteins such as AChE and neuroligins (75, 76) can also bind to I-II-III, but they are not able to perform the intramolecular rescue of I-II-III folding, stability, or secretion (78).

Figure 10.

Folding and secretion of truncated Tg segments. A, Autonomous folding and secretion of distinct Tg truncation mutations. From this we propose that folding the segment shown at bottom, including both linker and hinge regions, may be rate-limiting for Tg folding and export. See Section V for details. B, Intramolecular chaperone function of ChEL. ChEL rescues secretion of Tg region I-II-III. However, isolated II-III easily folds in the ER and is also rapidly secreted. Thus, the intramolecular rescue by ChEL appears to be directed mostly toward the improved folding stability of a portion of Tg region I. However, ChEL rescue of region I folding/stability requires the presence of II-III. See Section V for details.

A true molecular chaperone shows preferential binding to early folding intermediates over more/fully mature forms. In contrast, secretory ChEL shows preference for mature forms of I-II-III, and as noted above, it remains associated with I-II-III along the entire secretory pathway (3). Moreover, when ChEL was engineered to be retained in the ER (by appending to it the retention signal KDEL), ChEL-KDEL facilitated the oxidative maturation of I-II-III, but secretion of I-II-III was no longer promoted (3). Thus, ChEL stabilizes a well-folded form of I-II-III and functions as a molecular courier for Tg transport along the secretory pathway.

B. Dimerization function

Follicular 19S Tg (660 kDa, the predominant form of Tg in the thyroid follicle lumen) is a homodimer of two 12S monomers (330 kDa) assembled into a compact ovoid structure (122). However, formation of 19S Tg does not take place in the follicular lumen, but occurs rather in the ER before intracellular transport to the Golgi complex (9, 123). Moreover, inhibiting dimerization decreases the efficiency of Tg export from the ER and its ensuing secretion (124). These findings are in accordance with the view that acquisition of a proper quaternary structure is required for efficient secretory protein export from the ER (125).

Like AChE (66) and its related family members, ChEL undergoes homodimerization via formation of a four-helix bundle at its C-terminal end (71–73). Using the PSIPRED program for prediction of protein secondary structure (126), it was noted that sequences in the carboxyl-terminal portion of the Tg ChEL domain are also predicted with high confidence to form helical segments that are positioned identically to the dimerization helices of AChE (74). Indeed, the isolated ChEL domain was found capable of dimerization with full-length Tg (whereas isolated I-II-III cannot), whereas insertion of an N-linked glycan into the upstream dimerization helix inhibits homodimerization of the isolated ChEL domain. Indeed, even AChE and neuroligins can cross-dimerize with the Tg ChEL domain (although the dimers are less stable than those formed by ChEL with Tg). These results indicate that the ChEL domain in general, and these helices in particular, plays a role in Tg dimerization. However, addition of the same glycosylation site in full-length Tg did not efficiently block Tg dimerization and secretion. Thus, additional interactions involving upstream Tg regions with ChEL domain further stabilize the Tg dimer complex in a way that can overcome a modest insult to the four-helix bundle (74, 78). It is currently unknown whether the stable Tg dimer-formation and molecular courier functions represent the same ChEL binding associations or are two discrete interactions within the Tg molecule.

Cross-dimerization of ChEL despite the presence of modest structural insult to one of the dimerization partners (78) has interesting pathophysiological implications. In congenital hypothyroidism with defective Tg, an autosomal recessive trait, most patients bearing a mutant Tgn allele are heterozygotes. Importantly, through cross-dimerization in such heterozygous patients, it is formally possible that the ChEL domain from the wild-type gene product may suppress in trans the intracellular transport defect of the mutant gene product. For example, missense mutations in the ChEL domain of Tg from rodent models of congenital hypothyroidism (rdw/rdw homozygous G2300R [Refs. 127 and 128] and cog/cog homozygous L2263P [Ref. 129]) have been introduced into the homologous sequence within AChE, and not surprisingly they inhibit enzyme activity (82). Moreover, these mutations also block Tg homodimerization (130) and interfere with the molecular courier function of ChEL (3). However, when coexpressed with wild-type Tg, the mutant rdw-Tg cross-dimerizes with the wild-type protein, and secretion of rdw-Tg is partially restored (78). Thus, in patients heterozygous for mutant Tg, the possibility of (partial or total) trans-suppression of the mutant phenotype exists, which may help to account for the recessive phenotype.

The phenomenon of suppression in trans may also imply that different naturally occurring mutations within the Tg ChEL domain may have different cross-dimerization capability and/or different molecular courier activity (and different degrees of suppression of the disease phenotype in heterozygotes). This possibility suggests that some Tgn mutant heterozygotes may exhibit predisposition to mild hypothyroidism and goiter.

C. The challenges of folding Tg region I

The final step(s) of Tg conformational maturation appear(s) to involve a covalent plication of the protein as detected by a sudden jump in band mobility by nonreducing SDS-PAGE (55). This process has been referred to as the “D-to-E transition,” implying formation of one or two disulfide bonds engaging Cys partners that are normally separated by a significant distance along the primary sequence. In contrast, the vast majority of Tg disulfide bridges employ cysteines that form much shorter disulfide loops (see Section III.A.3). The nine type-1A and two type-1B repeats are thought to consume most or all of their internal thiols (36), and this is thought to occur also in type-2 and type-3 repeats (34), as well as in the ChEL domain (66, 79). Thus, it is likely that the long-range disulfide(s) involved in the D-to-E transition employ cysteines outside the repeats or ChEL units. Region I is particularly implicated in the long-range disulfide(s) because the oxidative folding of isolated region I appears to reproduce the D-to-E transition when it is expressed in the presence of II-III and ChEL (55). Naturally occurring mutation of Tg-C1245R is associated with Tg misfolding, leading to hypothyroidism and goiter (131, 132), and indeed mutation of Cys1245 (and to a lesser extent, Cys1489) inhibits the D-to-E transition, strongly implicating the hinge region in the formation of at least one long-range disulfide bond within Tg region I (55).

Within the many repeats of Tg region I, a truncation Tg-A340X, comprising precisely the first through fourth type-1 repeats, has also been found to function as an independent folding unit that is rapidly and efficiently secreted without assistance from other Tg regions (55) (Figure 10A). The transport competence of this truncated segment of region I suggests an evolutionary significance of this cluster comprised of the first four Tg type-1 that, remarkably, also encompasses the main T4-forming site at Tyr-5 and the DIT donor at Tyr-130. Presumably, expansion of this cluster with more Tg type-1 domains and insertions provided evolutionary benefit in iodide storage, even as it rendered the larger Tg protein more difficult to fold.

The isolated region I, especially that ranging from the hinge segment to the linker segment, is the most difficult part of Tg to fold (Figure 10A) and is in part responsible for the strong binding of Tg to BiP and GRP94 (56). Interestingly, ChEL rescues the isolated region I only in cells that also coexpress secretory II-III (Figure 10B), although ChEL does not bind to isolated II-III (56). These data suggest that conformational maturation of region I—particularly the portion from the linker to the hinge segment—is facilitated by the presence of both II-III and ChEL, altogether suggesting a ternary complex involving regions I + II-III + ChEL.

VI. Chaperones and Oxidoreductases That Play a Role in Tg Maturation

A. The CRT/CNX cycle

About 20–30% of proteins synthesized in eukaryotic cells are translocated into the lumen of the ER en route to their final destination. Of these, about 80% are N-glycosylated by transfer en bloc of the Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide by the action of the oligosaccharyl transferase complex (Figure 11) (133). Addition of N-glycans to the nascent polypeptide has two major consequences. First, by virtue of their hydrophilicity, glycans shield hydrophobic stretches on nascent proteins (134), increasing protein solubility and decreasing nonproductive interactions (135). Because the molecular chaperone BiP also binds hydrophobic stretches on nascent proteins (136, 137), N-linked glycosylation helps to limit BiP binding. Second, this modification shifts the selection of ER chaperones for assistance in protein folding. Specifically, N-linked glycans of nascent folding proteins attract the binding of calreticulin (CRT) and calnexin (CNX) that act as lectins for monoglucosylated-Man9GlcNAc2. Indeed, the distance from the N terminus to the first N-glycan can help determine whether the emerging polypeptide will interact first with these lectin-like chaperones or with BiP (138–140).

Figure 11.

Structure of N-linked core oligosaccharide added to the polypeptide chains.

The monoglucosylated N-glycan is initially generated by the action of glucosidase I (which produces doubly glucosylated-Man9GlcNAc2) and glucosidase II (which generates sequentially monoglucosylated-Man9GlcNAc2 and unglucosylated Man9GlcNAc2) (141–143). Thus, the action of glucosidase II first generates the monoglucosylation binding site for CRT/CNX but ultimately eliminates the binding site, preventing further CRT/ CNX association (Figure 11). Productive protein folding may occur either during the period of association with CRT/CNX (144–146) or immediately after dissociation from these lectin-like chaperones (133, 147). However, many proteins have domains that need more time to fold to the native state. Such non-native glycoproteins are recognized by UDP- Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase (UGGT), which restores one glucose to the A-branch of Man9GlcNAc2, regenerating monoglucosylated oligosaccharides that can rebind to CRT/CNX (Figure 11) (141, 142). In vitro studies have demonstrated that UGGT recognizes exposed hydrophobic patches situated C-terminal to the glycan (148). Although the severity of misfolding is correlated with the degree of reglucosylation (149), UGGT is not thought to recognize completely disordered conformations (150–152) that tend to be preferred by BiP.

Deglucosylation-reglucosylation reactions, catalyzed by sequential activities of glucosidase II and UGGT, continue to cycle until the glycoprotein is no longer processed by UGGT (which may signify that it has reached its native fold) or until it becomes degraded by the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway. Some glycoproteins may require only the single initial deglucosylation event and single round of binding to lectin-like chaperones en route to the native state; other substrates require multiple iterative rounds of reglucosylation and lectin-chaperone binding (146). For multidomain proteins like Tg, each round of reglucosylation allows that individual misfolded domain to selectively recruit CRT/CNX for folding assistance (152, 153), whereas other domains may engage other chaperones.

B. Substrate recognition by CRT/CNX

CRT and CNX possess identical oligosaccharide binding specificity (154–157), but their function is not identical because the newly synthesized protein substrates that they bind are not identical (154, 158, 159). Substrate selection by CRT and CNX may be related, at least in part, to protein folding context and topographic considerations (154, 158). CNX is a type-I membrane protein comprised of a globular domain that binds oligosaccharide and an extended P (proline-rich) domain (160), whereas CRT is a soluble protein containing an oligosaccharide-binding domain and a P domain (161). CNX is in close association with the translocon complex and may interact preferentially with membrane-associated glycans once they are exposed, whereas CRT tends to interact with glycans when they become more freely accessible in the ER lumen (162–164); thus CNX tends to interact first, whereas CRT interactions tend to peak thereafter (162). Consequently, CRT may have a preference for lumenal proteins, and CNX may have a preference for membrane proteins (154, 165). However, CNX substrates do not automatically associate with CRT upon selective CNX depletion; instead, they tend to associate with BiP (159). This finding suggests the possibility that substrate proteins not selected by CNX may tend to bypass the CRT/CNX cycle, instead utilizing distinct ER chaperones (138–140). In multidomain proteins, it is likely that some domains exhibit narrow specificity for selected ER chaperones, whereas others may be more promiscuous in chaperone binding.

C. Glycan-dependent oxidoreductase activity

The CRT/CNX chaperones can facilitate formation, isomerization, and reduction of disulfide bonds through the action of ERp57, a member of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family of ER oxidoreductases (166–168). ERp57 associates noncovalently with the P domain of either CRT or CNX (169). In addition there is an ERp57 pool associated with tapasin—a protein involved in MHC class I peptide loading (170–172). Independently of CRT/CNX, ERp57 can interact with no more than a small subset of secretory protein substrates (170, 171, 173).

ERp57 deletion is lethal at the whole organism level but is not at the cellular level—similar to that seen for CRT and CNX (174, 175). This is explained by the fact that only a finite number of proteins in an organism are strictly dependent on the CRT/CNX/ERp57 system for folding (Table 3); thus, there are backup folding systems operative at the cellular level. Indeed, ERp57 deletion may be compensated by the function of other oxidoreductases, such as ERp72 (176, 177).

Table 3.

Classification of Cellular Proteins Based on UGGT/CRT/CNX/ERp57 Requirement

| ER Chaperone Requirement | Substrate | Folding in ERp57−/− Cells | Folding in Castanospermine-Treated Cells | Small Disulfide-Rich Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do not prefer UGGT-CRT/CNX-ERp57 | Most cellular glycoproteins | Yes | Yes | No |

| Prefer (but do not require) UGGT-CRT/CNX-ERp57 | Clusterina | No | Yes | No |

| Require UGGT-CRT/CNX-ERp57 | β1 integrin (LDL-R) Tg | No | No | Yes |

Abbreviation: LDL-R, low-density lipoprotein receptor.

In ERp57−/− cells, clusterin is recruited to a nonfunctional cycle by the presence of CNX, whereas in castanospermine-treated cells, clusterin does not even enter the cycle and may adopt surrogate chaperones.

However, for a selected subset of glycoprotein substrates, there can be devastating consequences for the loss of ERp57 activity (176)—for example, β1 integrin does not fold in ERp57−/− cells or in cells treated with castanospermine so as to prevent formation of a monoglucosylated substrate (and thereby deny entry into the CRT/CNX cycle) (173, 177). A similar folding defect is observed upon expression of an ERp57-R282A mutant that does not bind CRT or CNX, indicating a requirement for these lectin-like chaperones (173). The “small disulfide-rich” domains of β1 integrin that ultimately engage all internal cysteines into intradomain disulfide bonds do have a high potential for disulfide mispairing during folding. Thus, the requirement for UGGT/CRT/CNX may be linked to ERp57-induced formation of proper disulfide bonds in small disulfide-rich domains (177). Another secretory glycoprotein, prosaposin (178), comprised of four small disulfide-rich domains and a single N-linked glycan (179), has similarly been found to be a prominent UGGT substrate that is acted upon by ERp57 (180). In UGGT−/− MEF cells, prosaposin secretion is impaired, and ER-retained prosaposin displays improper disulfide bond formation thought related to insufficient ERp57 engagement. Table 2 provides a list of cellular glycoproteins and their relative dependence upon UGGT/CRT/CNX/ERp57 for successful folding.

D. Glycoprotein ERAD

Trimming of mannose residues from N-linked glycans occurs as a part of successful transport of native-state glycoproteins and is a prerequisite for the formation of complex (Golgi-modified) glycans found on mature glycoproteins (181). Mannose trimming is also linked to processing of misfolded glycoproteins that are targeted for ERAD (182). There may be decreased efficiency of UGGT activity on lower mannose N-glycan forms (183) and decreased efficiency of ER glucosidase-II (184); both may limit further rounds of reglucosylation/deglucosylation, favoring release of misfolded glycoproteins from CRT/CNX and promoting ERAD (185).

For substrates entrapped in the ER, glycoproteins first tend to lose a “B-chain (middle branch) mannose” (Figure 11) (186)—indicative of ER mannosidase I (ER man-I) activity, which remains compatible with continued reglucosylation of the misfolded substrate by UGGT (187). ER man-I, which provides an α1,2-mannosidase activity, is implicated in ERAD based on evidence that the α1,2-mannosidase inhibitor, kifunensine, stabilizes glycoproteins that are normally degraded—including misfolded Tg (188). The mechanism of degradation includes recognition of the misfolded Man8 glycoprotein by EDEM-I (189, 190) that facilitates ERAD (189, 191). Additional components, including EDEM-3 and OS-9, may engage the remaining trimmed glycan (192) for subsequent delivery of the misfolded glycoprotein to the cytosol via retrotranslocation. Indeed, ER mannose trimming events appear to enhance ERAD efficiency (193). Conceivably, ER man-I could be responsible for N-glycan cleavage all the way down to the Man5GlcNAc2 form (Figure 11) (194), especially if the glycoprotein substrates are targeted to the pericentriolar “ER quality control compartment” where ER man-I is particularly concentrated (193). Ultimately, retrotranslocation initiated by OS-9 includes roles for SEL1 and HRD1 (189, 191). SEL1 together with HRD1 activates a transmembrane E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that promotes degradation of ubiquitylated ERAD substrates by cytosolic proteasomes (189).

E. Tg as a model substrate for CRT/CNX/ERp57 in secretory protein folding

Tg, with up to 60 disulfide bonds and between 10 and 15 N-linked oligosaccharides per Tg monomer (depending on the species) (61), is a good candidate to be a CRT/CNX/ERp57 client protein. Indeed, newly synthesized Tg interacts with CRT and CNX in a carbohydrate-dependent manner, with kinetics that are concomitant with the maturation of Tg intrachain disulfide bonds (10). Indeed, Tg is the first endogenous protein reported in ternary complexes with CRT and CNX in the ER of live cells (10).

Tg type-1 repeats share structural homology with the small disulfide-rich domains found in several proteins noted above (53, 54, 177) (see Section VI.C). These small disulfide-rich domains have a high potential to form non-native disulfide bonds and are substrates for the reductase activity of ERp57 (177); thus, Tg type-1 repeats could be a good target for CRT/CNX/ERp57. Consistent with this, when thyrocytes were treated with castanospermine to block Tg entry in the CRT/CNX cycle, the oxidative folding of Tg monomers and Tg dimerization was impaired, Tg association with BiP/GRP78 and GRP94 was increased, the ER stress response (including ERAD) was activated, and a partial Tg escape from ER quality control with increased secretion of free monomers yet decreased overall Tg secretion was evident (124).

F. Other oxidoreductases of the ER

Formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds (195) are catalyzed by multiple ER oxidoreductases that belong to the PDI family, comprising over 20 members (196–198). Formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds implies transient formation of a mixed disulfide between the enzyme and the substrate. Because it is believed that the time needed to complete one catalytic cycle of each oxidoreductase is quite short, the mixed disulfides are extremely short-lived. Recently, mutant oxidoreductases—so-called “trap mutants”—have been employed to prolong the half-life of these mixed disulfide species (177, 199).

G. Evidence of ER-oxidoreductase involvement in Tg folding

Even without the use of trap mutants, it has been possible to isolate several mixed disulfides between wild-type Tg and endogenous oxidoreductases, represented by “adduct bands A, B, and C” (124, 200). Because Tg adducts appear during the time course when Tg oxidative folding is ongoing (200), and because their resolution is not blocked by inhibition of ERAD (124), they most likely represent folding intermediates of Tg. One subcomponent within adduct B involves Tg-ERp57 complexes, and another subcomponent includes Tg-PDI complexes. Adduct A is enriched in Tg-ERp72 complexes, and adduct C is enriched in Tg-CaBP1 (the human P5) complexes. Interestingly, each adduct band contains not only the primary-associated ER oxidoreductase, but also lower levels of additional co-associated ER oxidoreductases. Thus, the same Tg molecule can simultaneously bind to more than one ER oxidoreductase, each working on its respective preferred binding site in a kinetically overlapping way (200).

In recent years, the concept of different “chaperone networks” has been raised. In this concept, a subset of ER chaperones constitutes a preformed network that can bind protein substrates as a unit (201). Different chaperone networks may be preassembled with specific oxidoreductases, as is the case for ERp57 with CRT/CNX (168, 176, 173) or for P5/CaBP1 with BiP (199). PDI, on the other hand, is thought to bind substrates directly through its b' domain (202). Indeed, for some oxidoreductases, substrate specificity may be linked to an interaction with a specific chaperone network. Thus, the simultaneous binding of different oxidoreductases to the same Tg molecule may also imply the simultaneous binding of different chaperone networks that can act on different Tg domains. Importantly, oxidative maturation of Tg appears to continue—seemingly within the adducts—in parallel with the oxidative maturation of Tg monomers. Presumably, this is because the adducts represent a small fraction of Tg molecules “caught in the act” of formation of a disulfide bond. If adducts A, B, and C formed along a linear folding pathway, then it would be expected that, as oxidation proceeds, Tg molecules would successively pass from A to B to C. However, adducts A, B, and C do not follow a precursor-product relationship. Thus it appears that, when engaged in an adduct enriched in a given chaperone/oxidoreductase complex, the Tg molecules are undergoing oxidative folding with assistance of that chaperone/oxidoreductase network (200), resulting in a finite number of parallel tracks of oxidative Tg folding leading to the native (transport-competent) state.

VII. Alternatives Within the Tg Folding Pathway

Large multidomain proteins are commonly thought to fold in the ER of eukaryotic cells in a sequential or vectorial manner (203, 204), although the low-density lipoprotein receptor is an exception to this view (205). During folding of the low-density lipoprotein receptor in the ER, non-native disulfide bonds between cysteines of different small disulfide-rich domains may form (205, 206), which are then isomerized via the function of ERp57 (177) and other oxidoreductases of the PDI family, as well as ERdj5 (207) that works in conjunction with BiP to play a profolding role distinct from its recognized role in misfolded glycoprotein degradation (208–211). For Tg, the difficult to fold region I is indeed comprised of small disulfide-rich domains (177). Thus, Tg type-1 repeats may form non-native disulfides that require the isomerase function of ERp57 in conjunction with CRT/CNX rebinding as directed by UGGT. Indeed, the association of ERp57 with Tg I-II-III can mostly be attributed to its binding to Tg region I (200). Interestingly, as noted above, ChEL must ultimately serve to stabilize one or more folded segments within Tg region I. Because ChEL also binds well to ERp57 (200), ChEL might possibly assist in part by recruiting CRT/CNX/ERp57 to region I to execute its intramolecular chaperone function. Moreover, in addition to ERp57, Tg folding is simultaneously promoted by a different chaperone/oxidoreductase network that operates in a parallel track (200). These features tend to support a nonsequential model of Tg folding involving several predominant intermediates, all of which are en route to the native state.

Experimental evidence suggests that the amino terminus of Tg starts to fold with assistance of the CRT/CNX cycle (124). The unfolded N-terminal type-1 repeats are likely to form non-native mixed disulfides, including with ER oxidoreductases (PDI, ERp72, CaBP1), thereby becoming favorable substrates of UGGT and subjected to numerous cycles of folding. Because other parts of Tg cotranslationally appear in the ER lumen, part II-III readily folds, and lastly, the ChEL domain emerges. This last domain may also be captured in the CRT/CNX/ERp57 cycle (the ChEL domain of human Tg has the first glycan at position 40) (61) and is brought into proximity of Tg region I to which it binds. The ChEL domain may complete its own folding in just one or few cycles, but once associated with region I, ChEL can assist in stabilizing Tg region I.

VIII. Understanding Mutations Causing Congenital Hypothyroidism

Congenital TH insufficiency affects 1 in 2000–4000 newborns (212). Early diagnosis and TH replacement are critical to promote normal growth and neurological development. Most countries have adopted primary newborn screening of TSH or TH levels. Causes of congenital hypothyroidism include: 1) thyroid dysgenesis and resistance to TSH, characterized by deficient thyroid gland development (for review, see Ref. 213); and 2) dyshormonogenesis, including defects in the NIS (214), pendrin (SLC26A4) (215), TPO (216), Duox 2 (217), Duox maturation factor 2 (217), iodotyrosine dehalogenase 1 (218), and Tg (219). Dyshormonogenesis comprises a heterogeneous spectrum of hypothyroidism with a typically enlarged thyroid (goiter) because of chronic stimulation by TSH that is elevated in response to the reduced circulating levels of TH. The various forms of congenital hypothyroidism are traditionally diagnosed on the basis of the presence of goiter, iodide uptake, serum Tg, and perchlorate discharge test (212). In particular, patients with Tg defects present with hypothyroidism and very low levels of serum Tg (220). However, all congenital hypothyroidism patients are ultimately treated with TH supplementation.