Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a source of bioactive fragments called matricryptins or matrikines resulting from the proteolytic cleavage of extracellular proteins (e.g., collagens, elastin, and laminins) and proteoglycans (e.g., perlecan). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), cathepsins, and bone-morphogenetic protein-1 release fragments, which regulate physiopathological processes including tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis, a pre-requisite for tumor growth. A number of matricryptins, and/or synthetic peptides derived from them, are currently investigated as potential anti-cancer drugs both in vitro and in animal models. Modifications aiming at improving their efficiency and their delivery to their target cells are studied. However, their use as drugs is not straightforward. The biological activities of these fragments are mediated by several receptor families. Several matricryptins may bind to the same matricellular receptor, and a single matricryptin may bind to two different receptors belonging or not to the same family such as integrins and growth factor receptors. Furthermore, some matricryptins interact with each other, integrins and growth factor receptors crosstalk and a signaling pathway may be regulated by several matricryptins. This forms an intricate 3D interaction network at the surface of tumor and endothelial cells, which is tightly associated with other cell-surface associated molecules such as heparan sulfate, caveolin, and nucleolin. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying the behavior of this network is required in order to optimize the development of matricryptins as anti-cancer agents.

Keywords: matricryptins, endostatin, matricellular receptors, interaction networks, anticancer drugs

Introduction

Matricryptins are biologically active fragments released from extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and glycosaminoglycans by proteases (Davis et al., 2000). We have extended the definition of matricryptins to the ectodomains of membrane collagens and membrane proteoglycans, which are released in the ECM by sheddases, and to fragments of ECM-associated enzymes such as lysyl oxidase, which initiates the covalent cross-linking of collagens and elastin, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which contribute to ECM remodeling (Ricard-Blum and Salza, 2014; Ricard-Blum and Vallet, 2015). The molecular functions of matricryptins and the biological processes they regulate have been reviewed with a focus on collagen and proteoglycan matricryptins (Ricard-Blum and Ballut, 2011), on matricryptins regulating tissue repair (Ricard-Blum and Salza, 2014), angiogenesis (Sund et al., 2010; Boosani and Sudhakar, 2011; Gunda and Sudhakar, 2013), cancer (Monboisse et al., 2014), and on the proteases releasing matricryptins (Ricard-Blum and Vallet, 2015).

Synthetic peptides and/or domains derived from matricryptin sequences and recapitulating their biological roles are also able to regulate angiogenesis and/or cancer in various tumor cells and cancer models (Rosca et al., 2011). They include sequences of tumstatin (He et al., 2010; Han et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015a), laminins (Kikkawa et al., 2013), endostatin (Morbidelli et al., 2003), endorepellin (Willis et al., 2013), and the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 (Ugarte-Berzal et al., 2012, 2014). Neither these peptides nor the ectodomains of membrane collagens and syndecans are described here due to space limitation. We focus on the major matricryptins, which control cancer, metastasis, and angiogenesis, a pre-requisite for tumor growth and a therapeutic target (Folkman, 1971; Welti et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2015), and on their receptors.

Regulation of angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis by matricryptins

Matricryptins regulate wound healing, fibrosis, inflammation, angiogenesis, and cancer and are involved in infectious and neurodegenerative diseases (Ricard-Blum and Ballut, 2011; Ricard-Blum and Salza, 2014; Ricard-Blum and Vallet, 2015). Most of the matricryptins regulating angiogenesis and tumor growth are derived from collagens IV and XVIII (Monboisse et al., 2014; Walia et al., 2015), elastin (Robinet et al., 2005; Pocza et al., 2008; Heinz et al., 2010), fibronectin (Ambesi et al., 2005), laminins (Tran et al., 2008), osteopontin (Bayless and Davis, 2001; Lund et al., 2009; Yamaguchi et al., 2012), MMPs (Bello et al., 2001; Ezhilarasan et al., 2009), proteoglycans (Goyal et al., 2011), and hyaluronan (Cyphert et al., 2015; Table 1). They are released from the ECM by a variety of proteinases (matrixins, adamalysins, tolloids, cathepsins, thrombin, and plasmin; Ricard-Blum and Vallet, 2015; Wells et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Matricryptins, receptors, and signaling pathways regulated by matricryptins in endothelial and tumor cells.

| Receptors | Matricryptins | Signaling pathways | Cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTEGRINS | ||||

| α1β1 | Arresten (α1 chain of collagen IV) | Inhibition of FAK/c-Raf/MEK1/2/ERK1/2/p38 MAPK pathway; Inhibition of hypoxia-induced expression of HIF 1α and VEGF | ECs | Sudhakar et al., 2005 |

| HSC-3 human tongue squamous carcinoma cells | Aikio et al., 2012 | |||

| α2β1 | Endorepellin (C-terminus of perlecan) | Activation of SHP-1 | ECs | Nyström et al., 2009 |

| Activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1; Dephosphorylation of VEGFR2; Down-regulation of VEGFA | ECs | Goyal et al., 2011 | ||

| Down-regulation of VEGFR2 | ECs | Poluzzi et al., 2014 | ||

| Procollagen I C-propeptide | HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells | Weston et al., 1994 | ||

| α3β1 | Tumstatin (α3 chain of collagen IV) | Integrin α3β1 is a trans-dominant inhibitor of integrin αv | ECs | Borza et al., 2006 |

| Canstatin (α2 chain of collagen IV) | ECs | Petitclerc et al., 2000 | ||

| α4β1 | N-terminal osteopontin fragment | HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells | Bayless and Davis, 2001 | |

| PEX domain of MMP-9 | Human chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells | Ugarte-Berzal et al., 2012 | ||

| α4β7 | N-terminal osteopontin fragment | RPMI 8866 human lymphoblastoid cell line | Green et al., 2001 | |

| α5β1 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) KD = 975 and 451 nM, 2 binding sites, soluble endostatin, immobilized full-length integrin; (Faye et al., 2009b) | Inhibition of FAK/c-Raf/MEK1/2/p38/ERK1 MAPK pathway | ECs | Sudhakar et al., 2003 |

| Induction of phosphatase-dependent activation of caveolin-associated Src family kinases | ECs | Wickström et al., 2002 | ||

| Induction of recruitment of α5β1 integrin into the raft fraction via a heparan sulfate proteoglycan-dependent mechanism. | ECs | Wickström et al., 2003 | ||

| Induction of Src-dependent activation of p190RhoGAP with concomitant decrease in RhoA activity and disassembly of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions | ||||

| Hemangioendothelioma-derived cells | Guo et al., 2015 | |||

| N-terminal osteopontin fragment | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma (SW480 cells) | Yokosaki et al., 2005 | ||

| α6β1 | Tumstatin (α3 chain of collagen IV) | ECs | Maeshima et al., 2000 | |

| α9β1 | N-terminal osteopontin fragment | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma (SW480 cells) | Yokosaki et al., 2005 | |

| αvβ3 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) KD = 1.2 μM and 501 nM, 2 binding sites, soluble endostatin, immobilized full-length integrin; (Faye et al., 2009b) | ECs | Rehn et al., 2001 | |

| Canstatin (α2 chain of collagen IV) | Induction of two apoptotic pathways through the activation of caspase-8 and caspase-9 | ECs | Magnon et al., 2005 | |

| Induction of caspase 9-dependent apoptotic pathway | Human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231) | Magnon et al., 2005 | ||

| ECs | Petitclerc et al., 2000 | |||

| Tumstatin (α3 chain of collagen IV) | Inhibition of Cap-dependent translation (protein synthesis) mediated by FAK/PI3K/Akt/mTOR/4E-BP1 pathway | ECs | Maeshima et al., 2000; Sudhakar et al., 2003 | |

| ECs | Petitclerc et al., 2000 | |||

| Inhibition of the activation of FAK, PI3K, protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), and mTOR | ECs | Maeshima et al., 2002 | ||

| It prevents the dissociation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E protein from 4E-binding protein 1 | ||||

| Stimulation of FAK and PI3K phosphorylation | Human metastatic melanoma cell line (HT-144) | Pasco et al., 2000 | ||

| Inhibition of the growth of tumors dependent on Akt/mTOR activation (functional PTEN required) | Human glioma cells | Kawaguchi et al., 2006 | ||

| Tetrastatin (α4 chain of collagen IV) KD = 148 nM (2-state model, soluble tetrastatin, immobilized full-length integrin) | Human melanoma cells (UACC-903) | Brassart-Pasco et al., 2012 | ||

| NC1 domain of α6 chain of collagen IV | ECs | Petitclerc et al., 2000 | ||

| Procollagen II N-propeptide | Human chondrosarcoma cell line (hCh-1) | Wang et al., 2010 | ||

| PEX domain of MMP-2 | ECs | Brooks et al., 1998 | ||

| N-terminal osteopontin fragment | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma (SW480 cells) | Yokosaki et al., 2005 | ||

| VGAPG, VGAP (elastin peptides) | Human melanoma cell lines (WM35 and HT168-M1) | Pocza et al., 2008 | ||

| αvβ5 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) | ECs | Rehn et al., 2001 | |

| Canstatin (α2 chain of collagen IV) | Induction of two apoptotic pathways through the activation of caspase-8 and caspase-9 | ECs | Magnon et al., 2005 | |

| Induction of caspase 9-dependent apoptotic pathway | Human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231) | Magnon et al., 2005 | ||

| ECs | Petitclerc et al., 2000 | |||

| Tumstatin (α3 chain of collagen IV) | ECs | Pedchenko et al., 2004 | ||

| Procollagen II N-propeptide | Human chondrosarcoma cell line (hCh-1) | Wang et al., 2010 | ||

| N-terminal osteopontin fragment | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma (SW480 cells) | Yokosaki et al., 2005 | ||

| αvβ6 | N-terminal osteopontin fragment | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma (SW480 cells) | Yokosaki et al., 2005 | |

| GROWTH FACTOR RECEPTORS | ||||

| VEGFR1 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) | ECs | Kim et al., 2002 | |

| Endorepellin (C-terminus of perlecan) KD = 1 nM (soluble endorepellin, immobilized ectodomain of VEGFR1) | ECs | Goyal et al., 2011 | ||

| VEGFR2 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) | Inhibition of VEGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR2 and activation of ERK, p38 MAPK, and p125FAK | ECs | Kim et al., 2002 |

| Endorepellin (C-terminus of perlecan) | Attenuation of VEGFA-evoked activation of VEGFR2 at Tyr1175 | ECs | Goyal et al., 2011 | |

| KD = 0.9 nM (soluble endorepellin, immobilized ectodomain of VEGFR2) | ||||

| Attenuation of both the PI3K/PDK1/Akt/mTOR and the PKC/JNK/AP1 pathways | ECs | Goyal et al., 2012 | ||

| Induction of the formation of the Peg3-Vps34-Beclin 1 autophagic complexes via inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway | ECs | Poluzzi et al., 2014 | ||

| Induction of autophagy through a VEGFR2 dependent but α2β1 integrin-independent pathway | ||||

| EGFR | Laminin-332 EGF-like (domain III) of the γ2 chain | Stimulation of EGFR phosphorylation; Induction of ERK phosphorylation | Human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231) | Schenk et al., 2003 |

| CHEMOKINE RECEPTORS | ||||

| CXCR2 | Proline-glycine-proline (collagen matrikine) | Activation of Rac1, increase in phosphorylation of ERK, PAK and VE-cadherin | ECs | Hahn et al., 2015 |

| HEPARAN SULFATE PROTEOGLYCANS | ||||

| Glypican-1 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) | ECs | Karumanchi et al., 2001 | |

| Glypican-4 | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) | ECs | Karumanchi et al., 2001 | |

| Syndecan-1 | LG45 domain of the α3 chain of laminin-332 | HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells | Carulli et al., 2012 | |

| Syndecan-4 | LG45 domain of the α3 chain of laminin-332 | HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells | Carulli et al., 2012 | |

| ELASTIN RECEPTOR COMPLEX | ||||

| Elastin receptor complex | Elastin peptides (xGxxPG sequences) | 67 kDa elastin binding protein (an alternatively spliced form of β-galactosidase) | ECs | Robinet et al., 2005 |

| Human melanoma cell lines (WM35 and HT168-M1) | Pocza et al., 2008 | |||

| GALECTIN-3 RECEPTOR | ||||

| Galectin-3 receptor | VGVAPG and VAPG (elastin peptides) | Human melanoma cell lines (WM35 and HT168-M1) | Pocza et al., 2008 | |

| LACTOSE-INSENSITIVE RECEPTOR | ||||

| Lactose-insensitive receptor | VGVAPG (elastin peptide) | M27 subline of murine Lewis lung carcinoma | Blood and Zetter, 1993 | |

| AGVPGLGVG and AGVPGFGAG (elastin peptides) | Human lung carcinoma cells | Toupance et al., 2012 | ||

| CD44, RHAMM AND TLR4 | ||||

| CD44 | Hyaluronan oligosaccharides (3–10 disaccharides) | PKC-α phosphorylation of γ-adducin, a membrane cytoskeletal and actin-binding protein, Activation of ERK1/2 | ECs | Matou-Nasri et al., 2009 |

| Stimulation of ERK1/2 signaling Inhibition of CD44 clustering (3–10 disaccharides) | Human breast cancer cells (BT-159, ductal carcinoma) | Yang et al., 2012 | ||

| N-terminal osteopontin fragment (Leu1-Gly127) | CD44-mediated OPN binding requires β1 integrin | Rat BDX2 fibrosarcoma cells | Katagiri et al., 1999 | |

| C-terminal osteopontin fragment (Leu132-Asn278) | CD44-mediated OPN binding requires β1 integrin | Rat BDX2 fibrosarcoma cells | Katagiri et al., 1999 | |

| Osteopontin fragment (5 kDa, residues 167–210) | Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells | Takafuji et al., 2007 | ||

| PEX domain of MMP-9 | Human chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells | Ugarte-Berzal et al., 2014 | ||

| LYVE-1 | Hyaluronan oligosaccharides (3–10 disaccharides) | Increased tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase Cα/βII and ERK1/2 | ECs | Wu et al., 2014 |

| TLR4 | Hyaluronan oligosaccharides (4, 6, 8-mer HA fragments) | ECs | Taylor et al., 2004 | |

| RHAMM | Hyaluronan oligosaccharides (2–10 disaccharides) | Activation of ERK1/2 | ECs | Gao et al., 2008 |

| Hyaluronan oligosaccharides (3–10 disaccharides) | Activation of ERK1/2 Up-regulation of cdk1/Cdc2 | Matou-Nasri et al., 2009 | ||

| CELL SURFACE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN | ||||

| Nucleolin | Endostatin (α1 chain of collagen XVIII) KD = 13 nM; (Shi et al., 2007) | Hemangioendothelioma-derived cells | Guo et al., 2015 | |

Receptors identified in other cell types and the associated signaling pathways are mentioned in the text. 4E-BP1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; AP1, activation protein 1; Cdk1/Cdc2, cyclin-dependent kinase-1; CXCR2, CXC chemokine receptor 2; CXCL1, Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1; EC, endothelial cell; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; LG, laminin G domain-like; LYVE-1, Lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; PAK, p21-activated kinase; PDK, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKB, protein kinase B; PKC, protein kinase C; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RHAMM, receptor for HA-mediated motility; SHP-1, Src homology-2 protein phosphatase-1; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; VE-cadherin, vascular endothelial cadherin; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFR, Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Matricryptins regulating angiogenesis and tumor growth target endothelial cells and/or tumor cells (Robinet et al., 2005; Tran et al., 2008; Sund et al., 2010; Boosani and Sudhakar, 2011; Ricard-Blum and Ballut, 2011; Toupance et al., 2012; Kikkawa et al., 2013; Monboisse et al., 2014; Ricard-Blum and Salza, 2014; Monslow et al., 2015; Nikitovic et al., 2015; Ricard-Blum and Vallet, 2015; Walia et al., 2015). Several matricryptins inhibit the proliferation and the migration of endothelial cells, block cell cycle at G1 as shown for anastellin (Ambesi et al., 2005) and endostatin (Hanai et al., 2002) and induce apoptosis. Arresten, derived from the C-terminus of the α1 chain of collagen IV, activates FasL mediated apoptosis for example (Verma et al., 2013). Endostatin and endorepellin, a matricryptin of perlecan, induce autophagy of endothelial cells, the autophagic activity of endorepellin being mediated by a VEGFR2-dependent pathway (Nguyen et al., 2009; Poluzzi et al., 2014). A modified endostatin (Endostar) induces autophagy in hepatoma cells (Wu et al., 2008). Matricryptins normalize tumor vasculature, which improves the delivery of cytotoxic drugs to the tumor and hence the response to anti-cancer treatments (Jain, 2005). Endostatin contributes to the normalization of tumor vasculature in a lung cancer model (Ning et al., 2012), and in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, where it enhances the effect of radiotherapy and reduces hypoxia (Zhu et al., 2015), possibly by a crosstalk between cancer and endothelial cells mediated by the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor and VEGF expression.

Matricryptins derived from collagens IV and XVIII target tumoral cells. Arresten inhibits migration and invasion of squamous cell carcinoma and induces their death (Aikio et al., 2012). Endostatin inhibits the proliferation of some cancer cells (e.g., the HT29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line) but not of others (e.g., the MDA-MB-231 human mammary adenocarcinoma cell line) (Ricard-Blum et al., 2004). Matricryptins enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to a cytotoxic drug and even reverse in part their resistance to this drug. A tumstatin peptide increases the sensitivity of non-small cell lung carcinoma cells to cisplatin (Wang et al., 2015c) and Endostar enhances the sensitivity to radiation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma xenografts in mice (Wen et al., 2009).

Matricryptins regulate angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis by various molecular mechanisms. The anti-angiogenic activities of tumstatin and endostatin contribute to tumor suppression by p53 via the upregulation of the α(II) collagen prolylyl hydroxylase (Folkman, 2006; Teodoro et al., 2006). Endostatin inhibits proliferation and migration of glioblastoma cells by inhibiting T-type Ca2+ channels (Zhang et al., 2012), and its ATPase activity contributes to its anti-angiogenic and antitumor properties (Wang et al., 2015b). This matricryptin inhibits hemangioendothelioma by downregulating chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 via the inactivation of NF–κB (Guo et al., 2015).

Receptors and co-receptors of matricryptins

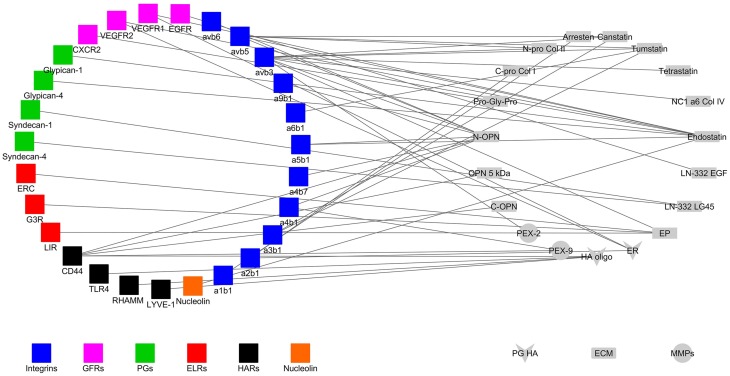

Matricryptins regulating angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis bind to several receptors, and co-receptors (Figure 1, Faye et al., 2009a) to modulate signaling pathways and fulfill their biological functions (Table 1). The other ligands of the receptors (e.g., ECM proteins, proteoglycans, growth factors, and chemokines) are not represented in Figure 1 for the sake of clarity. Pathways regulated by matricryptins in endothelial or tumor cells via unidentified receptors and/or in other cell types are mentioned below but are not listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Interaction network of matricryptins (right) and their receptors (left) expressed at the surface of endothelial and cancer cells. ab, alpha and beta integrin subunits; C-Pro Col, C-propeptide of procollagen; CXCR, chemokine CXC receptor; ECM, extracellular matrix; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EP, elastin peptide; ER, endorepellin; ERC, elastin receptor complex; ELR, elastin receptor; ES, endostatin; G3R, galectin-3 receptor; GFR, growth factor receptor; HA oligo, hyaluronan oligosaccharide; HAR, hyaluronan receptor; LN LG45, laminin domain LG45; LIR, lactose insensitive receptor; LYVE-1, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1; N-Pro Col, N-propeptide of procollagen; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NC1, non-collagenous domain; OPN, osteopontin; PEX, hemopexin domain; PG, proteoglycan; RHAMM, receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility; TLR4, toll-like receptor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Integrins

There are 24 integrins comprised of an α subunit and a β subunit (Barczyk et al., 2010). They lack intrinsic kinase activity and are the major adhesion receptors of the ECM, controlling ECM assembly, cell-matrix interactions, cell migration, and tumor growth (Missan and DiPersio, 2012; Xiong et al., 2013). A number of matricryptins bind to integrins at the surface of tumor and/or endothelial cells (Table 1). Matricryptins also interact with purified integrins (e.g., αvβ5 integrin for endostatin; Rehn et al., 2001; Faye et al., 2009b), or on other cell types. The αvβ3 integrin is the main receptor targeted by matricryptins (Figure 1).

Anastellin decreases the activation state of α5β1 integrin on endothelial cells (Ambesi and McKeown-Longo, 2014). Arresten interacts with α3β1/αvβ3 and α1β1/α2β1 integrins at the surface of HPV-16-immortalized proximal tubular epithelial cells and mesangial cells respectively, whereas tumstatin binds to immortalized glomerular epithelial cells through α3β1 and α2β1 integrins (Aggeli et al., 2009). The above integrins are also involved in the effects of matricryptins on other cell types. Endostatin, generated by cerebellar Purkinje cells, contributes to the organization of climbing fiber terminals in these neurons by binding and signaling through α3β1 integrin (Su et al., 2012). The adhesion of smooth muscle cells to anastellin is mediated by both β1 integrins and cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans, which triggers ERK1/2 activation in these cells (Mercurius and Morla, 2001) and the induction of osteoclast apoptosis by the N-propeptide of procollagen II is mediated by αv or β3 integrin subunits (Hayashi et al., 2011).

Growth factor and chemokine receptors

Growth factor receptors belong to the tyrosine kinase receptor family. They regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle, survival and apoptosis and play a role in cancer (McDonell et al., 2015). VEGR receptors 1–3 (Roskoski, 2008; Grünewald et al., 2010; Simons, 2012) and EGF receptor (Lemmon et al., 2014) interact with matricryptins (Table 1). Two endostatin peptides bind to VEGFR3 (Han et al., 2012, 2015) and EGF-like repeats of tenascin C interact with EGFR, inducing phosphorylation of the receptor and of ERK MAP kinases in NR6 mouse fibroblasts (Swindle et al., 2001). Endorepellin simultaneously engages VEGFR2 and α2β1 integrin, both expressed by endothelial cells, and regulate angiogenesis and autophagy through a dual receptor antagonism (Goyal et al., 2011; Poluzzi et al., 2014). Anastellin inhibits lysophospholipid (Ambesi and McKeown-Longo, 2009) and VEGF165-dependent signaling in endothelial cells by preventing the formation of the complex containing VEGFR2 and neuropilin-1 at the surface of endothelial cells (Ambesi and McKeown-Longo, 2014). One matricryptin of collagen I interacts with a member of the chemokine receptor family, the CXC chemokine receptor 2 (Stadtmann and Zarbock, 2012; Veenstra and Ransohoff, 2012).

Cell surface proteoglycans

Proteoglycans are divided into intracellular, pericellular, extracellular, and cell-surface families (Iozzo and Schaefer, 2015). Syndecans are transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans (Couchman et al., 2015), which play a role in cell adhesion, migration, receptor trafficking, growth factor interactions, angiogenesis (De Rossi and Whiteford, 2014) and cancer (Barbouri et al., 2014). They are enzymatically shed from the cell surface and compete with their membrane forms for ligand binding (Manon-Jensen et al., 2010). They act in synergy with integrins to control cell adhesion and other biological processes (Morgan et al., 2007; Roper et al., 2012; Humphries et al., 2015), and the binding of heparan sulfate chains to integrin α5β1 promotes cell adhesion and spreading (Faye et al., 2009b). Syndecans act as co-receptors of VEGF and control tumor progression in association with integrins (Grünewald et al., 2010; Soares et al., 2015). Glypicans, membrane-associated proteoglycans with a glycosylphosphatidyl anchor, regulate Wnt, Hedgehog, fibroblast growth factor, and bone morphogenetic protein signaling (Filmus et al., 2008; Iozzo and Schaefer, 2015). One matricryptin, endostatin, binds to glypicans via their heparan sulfate chains (Karumanchi et al., 2001).

Elastin receptors

The Elastin Receptor Complex (ERC) is composed of two membrane associated proteins (the protective protein/cathepsin A and neuraminidase-1) and of the elastin-binding protein, an inactive spliced variant of lysosomal β-galactosidase (Blanchevoye et al., 2013). Elastin peptides activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 via a Ras-independent mechanism in fibroblasts (Duca et al., 2005), the enzymatic activity of neuraminidase-1 being responsible for signal transduction (Duca et al., 2007). Another, still unidentified, receptor of elastin peptides exists at the surface of macrophages (Maeda et al., 2007). Furthermore, elastin peptides regulate tumor cell migration and invasion through an Hsp90-dependent mechanism (Donet et al., 2014).

CD44, receptor for HA-mediated motility (RHAMM) and toll-like receptors (TLRs)

Hyaluronan, a non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan, has two major receptors, CD44 and RHAMM, which mediate its roles in inflammation and cancer (Toole, 2009; Misra et al., 2015; Nikitovic et al., 2015). The binding to, and activation of, receptors depend on the size of HA, its oligosaccharides stimulating angiogenesis (Gao et al., 2008). CD44, which has several isoforms regulates cell proliferation, adhesion and migration, and is involved in tumorigenesis (Jordan et al., 2015). A sequence in the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 (PEX9) impairs tumor cell adhesion to PEX9/MMP9 through interaction with CD44 (Ugarte-Berzal et al., 2014). RHAMM has splicing variants and is located inside the cell and on the cell surface, where it is anchored via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (Tolg et al., 2014; Misra et al., 2015). Toll-like receptors are pattern recognition receptors involved in innate immunity (Rakoff-Nahoum and Medzhitov, 2009). Low-molecular weight hyaluronan induces the formation of a complex containing CD44, TLR2/TLR4, the actin filament-associated protein AFAP-110, and a myeloid differentiation factor MyD88, which triggers cytoskeleton activation and results in tumor invasion (Bourguignon et al., 2011).

Other membrane and cell surface-associated proteins

Matricryptins form complexes with membrane or membrane-associated proteins. Caveolin- participates in the formation of membrane caveolae, which are platforms for signal transduction (Fridolfsson et al., 2014) and forms a complex with α5β1 integrin and endostatin in lipid rafts at the endothelial cell surface (Wickström et al., 2002) (Table 1). Nucleolin, a multifunctional protein, localized inside the cell and at the cell surface (Berger et al., 2015), binds to endostatin and triggers its internalization in endothelial cells in association with the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor and the α5β1integrin (Shi et al., 2007; Song et al., 2012).

Matricryptins as potential drugs

Matricryptins are potential anti-cancer drugs, either alone, or in combination with other treatments, but their use in pre-clinical and clinical studies remains challenging. Indeed matricryptins may display opposite activities depending on the context. The anti-tumoral effect of endostatin is enhanced by silencing of the proteoglycan versican, which decreases the inflammatory and immunosuppressive changes triggered by anti-angiogenic therapy (Wang et al., 2015d). However, endostatin may induce the proliferation of carcinoma cells, whereas its effect on cancer invasion is modulated by the tumor microenvironment (Alahuhta et al., 2015). Endorepellin stimulates angiogenesis in a stroke model by increasing VEGF levels, and exerts a neuroprotective effect in this model via α5β1 integrin and VEGFR2 (Lee et al., 2011). In addition, endostatin exhibits a biphasic response curve both for its anti-angiogenic and anti-tumoral properties (Celik et al., 2005; Javaherian et al., 2011), which requires to test a large range of concentrations to determine the optimal dose for treatment. Another challenge is that matricryptins may themselves contain cryptic sequences displaying opposite activities as reported for the anti-angiogenic matricryptin endostatin, which contains an embedded pro-angiogenic sequence (Morbidelli et al., 2003). Different matricryptins regulate the same biological process in an opposite way as reported for the regulation of the angiogenic signaling in choroidal endothelial cells by hexastatin and elastokines (Gunda and Sudhakar, 2013), or distinct steps of a biological process as described for anastellin and endostatin (Neskey et al., 2008).

Matricryptins can be modified to extend the half-life, and their efficacy (Xu et al., 2007; Zheng, 2009; Ricard-Blum and Ballut, 2011; Ricard-Blum and Salza, 2014). Most of the examples detailed below concern endostatin, which is extensively studied and has been approved for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer in China (Biaoxue et al., 2012) under a recombinant form, Endostar, which contains an extra metal chelating sequence (MGGSHHHHH) at the N-terminus enhancing its solubility and stability (Jiang et al., 2009). PEGylation (Nie et al., 2006; Tong et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2014), and the fusion of endostatin to low molecular weight heparin or to the Fc region of an IgG enhance its half-life and its anti-angiogenic, or anti-tumoral activities (Lee et al., 2008; Jing et al., 2011; Ning et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015b).

Tumors may escape from anti-tumoral and anti-angiogenic matricryptins by upregulating factors, which stimulate angiogenesis (Fernando et al., 2008). The combination of matricryptins with inhibitors of pro-angiogenic pathways, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy enhance their therapeutic efficacy. Tumstatin has been fused to another endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis, vasostatin (Gu et al., 2014) and to tumor necrosis factor α, which has anti-tumoral and anti-angiogenic properties, which results in a more effective fusion protein than tumstatin alone (Luo et al., 2006). Endostatin has been fused to the proapoptotic domain (BH3) of the BAX protein (Chura-Chambi et al., 2014), to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (Zheng et al., 2013) and one of its anti-angiogenic sequences to an heptapeptide inhibitor of MMPs (Qiu et al., 2013). Endostatin has also been fused to protein sequences targeting it to tumors and/or tumor vasculature such as humanized antibodies against tyrosine kinase-type receptor HER2 (Shin et al., 2011) or against tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 highly expressed in human tumor tissues (Lee et al., 2015), the RGD integrin-binding sequence (Jing et al., 2011), and a liver-targeting peptide (circumsporozoite protein CSP I-plus (Ma et al., 2014; Bao et al., 2015).

Several approaches improve the delivery of matricryptins to tumors and endothelial cells (Xu et al., 2007; Ricard-Blum and Ballut, 2011) such as conditionally replicating oncolytic adenoviral vector for arresten (Li et al., 2015a), naked plasmid electrotransfer in muscle for tumstatin overexpression (Thevenard et al., 2013), and the nonpathogenic and anaerobic bacterium, Bifidobacterium longum, which proliferates in the hypoxic zones within tumors for tumstatin expression (Wei et al., 2015). Endostatin has been delivered in polylactic acid nanoparticles (Hu and Zhang, 2010), in gold nanoshells, which are very efficient on lung cancer cells when associated with near-infrared thermal therapy (Luo et al., 2015) and into microbubbles in combination with ultrasonic radiation in a cancer model (Zhang et al., 2014). Dendrimers mimicking the surface structure of endostatin and loaded with anticancer drug, result in both angiogenesis inhibition by endostatin and death of cancer cells by the anticancer drug (Jain and Jain, 2014).

Clinical trials of endostatin mostly focus on solid tumors in association with cytotoxic drugs (https://clinicaltrials.gov/). These trials include phase I (Lin et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2014), II (Lu et al., 2015), and III trials (Wang et al., 2005). Although endostatin did not improve overall survival, progression-free survival, and objective response rate when combined with etoposide and carboplatin in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer phase II trial (Lu et al., 2015), it significantly improves the response rate and median time to tumor progression when combined with vinorelbine and cisplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients compared to chemotherapy alone (Wang et al., 2005). Promising results have been obtained with endostatin associated with paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracile in patients with refractory malignant ascites secondary to ovarian cancer (Zhao et al., 2014).

Concluding remarks

Several matricryptins such as the propeptide of lysyl oxidase, which is a tumor suppressor (Min et al., 2007; Ozdener et al., 2015) and the netrin-like domain of procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1, a new anti-angiogenic matricryptin (Salza et al., 2014), warrant further investigation in angiogenesis, and tumor models to decipher their mechanisms of action at the molecular and cellular levels. Matricryptins are useful for treating fibroproliferative disorders (Yamaguchi et al., 2012; Wan et al., 2013) and fundus oculi angiogenesis diseases (Zhang et al., 2015). The finding that a peptide derived from endostatin can be delivered orally in vivo and exerts anti-fibrotic activity (Nishimoto et al., 2015) paves the way for the development of new matricryptin drugs with oral bioavailability, which is a preferred administration route for long-term treatment. Matricryptins are also used as biomarkers in serum and in cerebrospinal fluid (Ricard-Blum and Vallet, 2015; Salza et al., 2015) and may serve as imaging agents when labeled with (99m)Tc as shown for endostatin (Leung, 2004) and tumstatin (He et al., 2015) and for tumstatin conjugated to iron oxide nanoparticles (Ho et al., 2012).

Author contributions

SV drafted the Section Receptors and Co-receptors of Matricryptins and Table 1 and made the figure. SB made bibliographical searches for all the sections and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- HA

hyaluronan

- MAPK

mitogen-associated protein kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- RHAMM

receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

References

- Aggeli A. S., Kitsiou P. V., Tzinia A. K., Boutaud A., Hudson B. G., Tsilibary E. C. (2009). Selective binding of integrins from different renal cell types to the NC1 domain of alpha3 and alpha1 chains of type IV collagen. J. Nephrol. 22, 130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikio M., Alahuhta I., Nurmenniemi S., Suojanen J., Palovuori R., Teppo S., et al. (2012). Arresten, a collagen-derived angiogenesis inhibitor, suppresses invasion of squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 7:e51044. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alahuhta I., Aikio M., Väyrynen O., Nurmenniemi S., Suojanen J., Teppo S., et al. (2015). Endostatin induces proliferation of oral carcinoma cells but its effect on invasion is modified by the tumor microenvironment. Exp. Cell Res. 336, 130–140. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambesi A., Klein R. M., Pumiglia K. M., McKeown-Longo P. J. (2005). Anastellin, a fragment of the first type III repeat of fibronectin, inhibits extracellular signal-regulated kinase and causes G(1) arrest in human microvessel endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 65, 148–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambesi A., McKeown-Longo P. J. (2009). Anastellin, the angiostatic fibronectin peptide, is a selective inhibitor of lysophospholipid signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 255–265. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambesi A., McKeown-Longo P. J. (2014). Conformational remodeling of the fibronectin matrix selectively regulates VEGF signaling. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3805–3816. 10.1242/jcs.150458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao D., Jin X., Ma Y., Zhu J. (2015). Comparison of the structure and biological activities of wild-type and mutant liver-targeting peptide modified recombinant human endostatin (rES-CSP) in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 Cells. Protein Pept. Lett. 22, 470–479. 10.2174/0929866522666150302125218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbouri D., Afratis N., Gialeli C., Vynios D. H., Theocharis A. D., Karamanos N. K. (2014). Syndecans as modulators and potential pharmacological targets in cancer progression. Front. Oncol. 4:4. 10.3389/fonc.2014.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barczyk M., Carracedo S., Gullberg D. (2010). Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 339, 269–280. 10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless K. J., Davis G. E. (2001). Identification of dual alpha 4beta1 integrin binding sites within a 38 amino acid domain in the N-terminal thrombin fragment of human osteopontin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13483–13489. 10.1074/jbc.M011392200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello L., Lucini V., Carrabba G., Giussani C., Machluf M., Pluderi M., et al. (2001). Simultaneous inhibition of glioma angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and invasion by a naturally occurring fragment of human metalloproteinase-2. Cancer Res. 61, 8730–8736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger C. M., Gaume X., Bouvet P. (2015). The roles of nucleolin subcellular localization in cancer. Biochimie 113, 78–85. 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaoxue R., Shuanying Y., Wei L., Wei Z., Zongjuan M. (2012). Systematic review and meta-analysis of Endostar (rh-endostatin) combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 10:170. 10.1186/1477-7819-10-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchevoye C., Floquet N., Scandolera A., Baud S., Maurice P., Bocquet O., et al. (2013). Interaction between the elastin peptide VGVAPG and human elastin binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1317–1328. 10.1074/jbc.M112.419929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blood C. H., Zetter B. R. (1993). Laminin regulates a tumor cell chemotaxis receptor through the laminin-binding integrin subunit alpha 6. Cancer Res. 53, 2661–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boosani C. S., Sudhakar Y. A. (2011). Proteolytically derived endogenous angioinhibitors originating from the extracellular matrix. Pharm. Basel Switz. 4, 1551–1577. 10.3390/ph4121551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza C. M., Pozzi A., Borza D.-B., Pedchenko V., Hellmark T., Hudson B. G., et al. (2006). Integrin alpha3beta1, a novel receptor for alpha3(IV) noncollagenous domain and a trans-dominant Inhibitor for integrin alphavbeta3. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20932–20939. 10.1074/jbc.M601147200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon L. Y. W., Wong G., Earle C. A., Xia W. (2011). Interaction of low molecular weight hyaluronan with CD44 and toll-like receptors promotes the actin filament-associated protein 110-actin binding and MyD88-NFκB signaling leading to proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production and breast tumor invasion. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 68, 671–693. 10.1002/cm.20544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassart-Pasco S., Sénéchal K., Thevenard J., Ramont L., Devy J., Di Stefano L., et al. (2012). Tetrastatin, the NC1 domain of the α4(IV) collagen chain: a novel potent anti-tumor matrikine. PLoS ONE 7:e29587. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks P. C., Silletti S., von Schalscha T. L., Friedlander M., Cheresh D. A. (1998). Disruption of angiogenesis by PEX, a noncatalytic metalloproteinase fragment with integrin binding activity. Cell 92, 391–400. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80931-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulli S., Beck K., Dayan G., Boulesteix S., Lortat-Jacob H., Rousselle P. (2012). Cell surface proteoglycans syndecan-1 and -4 bind overlapping but distinct sites in laminin α3 LG45 protein domain. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 12204–12216. 10.1074/jbc.M111.300061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik I., Sürücü O., Dietz C., Heymach J. V., Force J., Höschele I., et al. (2005). Therapeutic efficacy of endostatin exhibits a biphasic dose-response curve. Cancer Res. 65, 11044–11050. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Du Y., Li P., Wu F., Fu Y., Li Z., et al. (2014). Phase I trial of M2ES, a novel polyethylene glycosylated recombinant human endostatin, plus gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2, 586–590. 10.3892/mco.2014.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chura-Chambi R. M., Bellini M. H., Jacysyn J. F., Andrade L. N., Medina L. P., Prieto-da-Silva A. R. B., et al. (2014). Improving the therapeutic potential of endostatin by fusing it with the BAX BH3 death domain. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1371. 10.1038/cddis.2014.309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman J. R., Gopal S., Lim H. C., Nørgaard S., Multhaupt H. A. B. (2015). Syndecans: from peripheral coreceptors to mainstream regulators of cell behaviour. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 96, 1–10. 10.1111/iep.12112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyphert J. M., Trempus C. S., Garantziotis S. (2015). Size Matters: molecular weight specificity of hyaluronan effects in cell biology. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2015:563818. 10.1155/2015/563818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. E., Bayless K. J., Davis M. J., Meininger G. A. (2000). Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am. J. Pathol. 156, 1489–1498. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65020-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi G., Whiteford J. R. (2014). Syndecans in angiogenesis and endothelial cell biology. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42, 1643–1646. 10.1042/BST20140232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donet M., Brassart-Pasco S., Salesse S., Maquart F.-X., Brassart B. (2014). Elastin peptides regulate HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cell migration and invasion through an Hsp90-dependent mechanism. Br. J. Cancer 111, 139–148. 10.1038/bjc.2014.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duca L., Blanchevoye C., Cantarelli B., Ghoneim C., Dedieu S., Delacoux F., et al. (2007). The elastin receptor complex transduces signals through the catalytic activity of its Neu-1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12484–12491. 10.1074/jbc.M609505200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duca L., Lambert E., Debret R., Rothhut B., Blanchevoye C., Delacoux F., et al. (2005). Elastin peptides activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 via a Ras-independent mechanism requiring both p110gamma/Raf-1 and protein kinase A/B-Raf signaling in human skin fibroblasts. Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 1315–1324. 10.1124/mol.104.002725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezhilarasan R., Jadhav U., Mohanam I., Rao J. S., Gujrati M., Mohanam S. (2009). The hemopexin domain of MMP-9 inhibits angiogenesis and retards the growth of intracranial glioblastoma xenograft in nude mice. Int. J. Cancer 124, 306–315. 10.1002/ijc.23951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye C., Chautard E., Olsen B. R., Ricard-Blum S. (2009a). The first draft of the endostatin interaction network. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22041–22047. 10.1074/jbc.M109.002964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye C., Moreau C., Chautard E., Jetne R., Fukai N., Ruggiero F., et al. (2009b). Molecular interplay between endostatin, integrins, and heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22029–22040. 10.1074/jbc.M109.002840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando N. T., Koch M., Rothrock C., Gollogly L. K., D'Amore P. A., Ryeom S., et al. (2008). Tumor escape from endogenous, extracellular matrix-associated angiogenesis inhibitors by up-regulation of multiple proangiogenic factors. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1529–1539. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmus J., Capurro M., Rast J. (2008). Glypicans. Genome Biol. 9:224. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. (1971). Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 285, 1182–1186. 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. (2006). Tumor suppression by p53 is mediated in part by the antiangiogenic activity of endostatin and tumstatin. Sci. STKE 2006:pe35. 10.1126/stke.3542006pe35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson H. N., Roth D. M., Insel P. A., Patel H. H. (2014). Regulation of intracellular signaling and function by caveolin. FASEB J. 28, 3823–3831. 10.1096/fj.14-252320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Yang C. X., Mo W., Liu Y. W., He Y. Q. (2008). Hyaluronan oligosaccharides are potential stimulators to angiogenesis via RHAMM mediated signal pathway in wound healing. Clin. Investig. Med. 31, E106–E116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Pal N., Concannon M., Paul M., Doran M., Poluzzi C., et al. (2011). Endorepellin, the angiostatic module of perlecan, interacts with both the α2β1 integrin and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2): a dual receptor antagonism. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25947–25962. 10.1074/jbc.M111.243626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Poluzzi C., Willis C. D., Smythies J., Shellard A., Neill T., et al. (2012). Endorepellin affects angiogenesis by antagonizing diverse vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)-evoked signaling pathways: transcriptional repression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and VEGFA and concurrent inhibition of nuclear factor of activated T cell 1 (NFAT1) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 43543–43556. 10.1074/jbc.M112.401786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P. M., Ludbrook S. B., Miller D. D., Horgan C. M., Barry S. T. (2001). Structural elements of the osteopontin SVVYGLR motif important for the interaction with alpha(4) integrins. FEBS Lett. 503, 75–79. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02690-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünewald F. S., Prota A. E., Giese A., Ballmer-Hofer K. (2010). Structure-function analysis of VEGF receptor activation and the role of coreceptors in angiogenic signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 567–580. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Sun C., Luo J., Zhang T., Wang L. (2014). Inhibition of angiogenesis by a synthetic fusion protein VTF derived from vasostatin and tumstatin. Anticancer. Drugs 25, 1044–1051. 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunda V., Sudhakar Y. A. (2013). Regulation of tumor angiogenesis and choroidal neovascularization by endogenous angioinhibitors. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 5, 417–426. 10.4172/1948-5956.1000235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Geng X., Chen Y., Qi F., Liu L., Miao Y., et al. (2014). Pre-clinical toxicokinetics and safety study of M2ES, a PEGylated recombinant human endostatin, in rhesus monkeys. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 69, 512–523. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Song N., He T., Qi F., Zheng S., Xu X.-G., et al. (2015). Endostatin inhibits the tumorigenesis of hemangioendothelioma via downregulation of CXCL1. Mol. Carcinog. 54, 1340–1353. 10.1002/mc.22210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C. S., Scott D. W., Xu X., Roda M. A., Payne G. A., Wells J. M., et al. (2015). The matrikine N-α-PGP couples extracellular matrix fragmentation to endothelial permeability. Sci. Adv. 1:e1500175. 10.1126/sciadv.1500175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K.-Y., Azar D. T., Sabri A., Lee H., Jain S., Lee B.-S., et al. (2012). Characterization of the interaction between endostatin short peptide and VEGF receptor 3. Protein Pept. Lett. 19, 969–974. 10.2174/092986612802084465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K.-Y., Chang M., Ying H.-Y., Lee H., Huang Y.-H., Chang J.-H., et al. (2015). Selective binding of endostatin peptide 4 to recombinant VEGF receptor 3 in vitro. Protein Pept. Lett. 22, 1025–1030. 10.2174/0929866522666150907111953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanai J., Dhanabal M., Karumanchi S. A., Albanese C., Waterman M., Chan B., et al. (2002). Endostatin causes G1 arrest of endothelial cells through inhibition of cyclin D1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16464–16469. 10.1074/jbc.M112274200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S., Wang Z., Bryan J., Kobayashi C., Faccio R., Sandell L. J. (2011). The type II collagen N-propeptide, PIIBNP, inhibits cell survival and bone resorption of osteoclasts via integrin-mediated signaling. Bone 49, 644–652. 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Hao Y., Long W., Song N., Fan S., Meng A. (2015). Exploration of peptide T7 and its derivative as integrin αvβ3-targeted imaging agents. OncoTargets Ther. 8, 1483–1491. 10.2147/OTT.S82095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Jiang Y., Li Y.-J., Liu X.-H., Zhang L., Liu L.-J., et al. (2010). 19-peptide, a fragment of tumstatin, inhibits the growth of poorly differentiated gastric carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 25, 935–941. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06209.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A., Jung M. C., Duca L., Sippl W., Taddese S., Ihling C., et al. (2010). Degradation of tropoelastin by matrix metalloproteinases–cleavage site specificities and release of matrikines. FEBS J. 277, 1939–1956. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. N., Kohler N., Sigdel A., Kalluri R., Morgan J. R., Xu C., et al. (2012). Penetration of endothelial cell coated multicellular tumor spheroids by iron oxide nanoparticles. Theranostics 2, 66–75. 10.7150/thno.3568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Zhang Y. (2010). Endostar-loaded PEG-PLGA nanoparticles: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Nanomed. 5, 1039–1048. 10.2147/IJN.S14753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Lan H., Liu F., Wang S., Chen X., Jin K., et al. (2015). Anti-angiogenesis or pro-angiogenesis for cancer treatment: focus on drug distribution. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 8369–8376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries J. D., Paul N. R., Humphries M. J., Morgan M. R. (2015). Emerging properties of adhesion complexes: what are they and what do they do? Trends Cell Biol. 25, 388–397. 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo R. V., Schaefer L. (2015). Proteoglycan form and function: A comprehensive nomenclature of proteoglycans. Matrix Biol. J. 42, 11–55. 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain K., Jain N. K. (2014). Surface engineered dendrimers as antiangiogenic agent and carrier for anticancer drug: dual attack on cancer. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 5075–5087. 10.1166/jnn.2014.8677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R. K. (2005). Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science 307, 58–62. 10.1126/science.1104819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaherian K., Lee T.-Y., Tjin Tham Sjin R. M., Parris G. E., Hlatky L. (2011). Two Endogenous antiangiogenic inhibitors, endostatin and angiostatin, demonstrate biphasic curves in their antitumor profiles. Dose Response. 9, 369–376. 10.2203/dose-response.10-020.Javaherian [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.-P., Zou C., Yuan X., Luo W., Wen Y., Chen Y. (2009). N-terminal modification increases the stability of the recombinant human endostatin in vitro. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 54, 113–120. 10.1042/BA20090063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y., Lu H., Wu K., Subramanian I. V., Ramakrishnan S. (2011). Inhibition of ovarian cancer by RGD-P125A-endostatin-Fc fusion proteins. Int. J. Cancer 129, 751–761. 10.1002/ijc.25932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A. R., Racine R. R., Hennig M. J. P., Lokeshwar V. B. (2015). The Role of CD44 in Disease Pathophysiology and Targeted Treatment. Front. Immunol. 6:182. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karumanchi S. A., Jha V., Ramchandran R., Karihaloo A., Tsiokas L., Chan B., et al. (2001). Cell surface glypicans are low-affinity endostatin receptors. Mol. Cell 7, 811–822. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00225-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri Y. U., Sleeman J., Fujii H., Herrlich P., Hotta H., Tanaka K., et al. (1999). CD44 variants but not CD44s cooperate with beta1-containing integrins to permit cells to bind to osteopontin independently of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid, thereby stimulating cell motility and chemotaxis. Cancer Res. 59, 219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi T., Yamashita Y., Kanamori M., Endersby R., Bankiewicz K. S., Baker S. J., et al. (2006). The PTEN/Akt pathway dictates the direct alphaVbeta3-dependent growth-inhibitory action of an active fragment of tumstatin in glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 66, 11331–11340. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa Y., Hozumi K., Katagiri F., Nomizu M., Kleinman H. K., Koblinski J. E. (2013). Laminin-111-derived peptides and cancer. Cell Adhes. Migr. 7, 150–256. 10.4161/cam.22827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-M., Hwang S., Kim Y.-M., Pyun B.-J., Kim T.-Y., Lee S.-T., et al. (2002). Endostatin blocks vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated signaling via direct interaction with KDR/Flk-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27872–27879. 10.1074/jbc.M202771200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B., Clarke D., Al Ahmad A., Kahle M., Parham C., Auckland L., et al. (2011). Perlecan domain V is neuroprotective and proangiogenic following ischemic stroke in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3005–3023. 10.1172/JCI46358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-H., Jeung I. C., Park T. W., Lee K., Lee D. G., Cho Y.-L., et al. (2015). Extension of the in vivo half-life of endostatin and its improved anti-tumor activities upon fusion to a humanized antibody against tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 in a mouse model of human colorectal carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 7182–7194. 10.18632/oncotarget.3121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.-Y., Tjin Tham Sjin R. M., Movahedi S., Ahmed B., Pravda E. A., Lo K.-M., et al. (2008). Linking antibody Fc domain to endostatin significantly improves endostatin half-life and efficacy. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1487–1493. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A., Schlessinger J., Ferguson K. M. (2014). The EGFR family: not so prototypical receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6:a020768. 10.1101/cshperspect.a020768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung K. (2004). (99m)Tc-Ethylenedicysteine-endostatin, in Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database (MICAD). (Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US)). Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK23681/ (Accessed November 16, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Qi Z., Li H., Hu J., Wang D., Wang X., et al. (2015a). Conditionally replicating oncolytic adenoviral vector expressing arresten and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand experimentally suppresses lung carcinoma progression. Mol. Med. Rep. 12, 2068–2074. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.-N., Yuan Z.-F., Mu G.-Y., Hu M., Cao L.-J., Zhang Y.-L., et al. (2015b). Inhibitory effect of polysulfated heparin endostatin on alkali burn induced corneal neovascularization in rabbits. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 8, 234–238. 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2015.02.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Huang H., Li S., Li H., Li Y., Cao Y., et al. (2007). A phase I clinical trial of an adenovirus-mediated endostatin gene (E10A) in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 648–653. 10.4161/cbt.6.5.4004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S., Li L., Luo Y., Zhang L., Wu G., Chen Z., et al. (2015). A multicenter, open-label, randomized phase II controlled study of rh-endostatin (Endostar) in combination with chemotherapy in previously untreated extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 10, 206–211. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund S. A., Giachelli C. M., Scatena M. (2009). The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 3, 311–322. 10.1007/s12079-009-0068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Xu M., Zhu X., Zhao J., Man S., Zhang H. (2015). Lung cancer cellular apoptosis induced by recombinant human endostatin gold nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 8758–8766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.-Q., Wang L.-H., Ma X.-L., Kong J.-X., Jiao B.-H. (2006). Construction, expression, and characterization of a new targeted bifunctional fusion protein: tumstatin45-132-TNF. IUBMB Life 58, 647–653. 10.1080/15216540600981743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Jin X.-B., Chu F.-J., Bao D.-M., Zhu J.-Y. (2014). Expression of liver-targeting peptide modified recombinant human endostatin and preliminary study of its biological activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 7923–7933. 10.1007/s00253-014-5818-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda I., Mizoiri N., Briones M. P. P., Okamoto K. (2007). Induction of macrophage migration through lactose-insensitive receptor by elastin-derived nonapeptides and their analog. J. Pept. Sci. 13, 263–268. 10.1002/psc.845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima Y., Colorado P. C., Kalluri R. (2000). Two RGD-independent alpha vbeta 3 integrin binding sites on tumstatin regulate distinct anti-tumor properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23745–23750. 10.1074/jbc.C000186200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima Y., Sudhakar A., Lively J. C., Ueki K., Kharbanda S., Kahn C. R., et al. (2002). Tumstatin, an endothelial cell-specific inhibitor of protein synthesis. Science 295, 140–143. 10.1126/science.1065298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnon C., Galaup A., Mullan B., Rouffiac V., Bouquet C., Bidart J.-M., et al. (2005). Canstatin acts on endothelial and tumor cells via mitochondrial damage initiated through interaction with alphavbeta3 and alphavbeta5 integrins. Cancer Res. 65, 4353–4361. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manon-Jensen T., Itoh Y., Couchman J. R. (2010). Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J. 277, 3876–3889. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matou-Nasri S., Gaffney J., Kumar S., Slevin M. (2009). Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan induce angiogenesis through distinct CD44 and RHAMM-mediated signalling pathways involving Cdc2 and gamma-adducin. Int. J. Oncol. 35, 761–773. 10.3892/ijo_00000389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonell L. M., Kernohan K. D., Boycott K. M., Sawyer S. L. (2015). Receptor tyrosine kinase mutations in developmental syndromes and cancer: two sides of the same coin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, R60–R66. 10.1093/hmg/ddv254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurius K. O., Morla A. O. (2001). Cell adhesion and signaling on the fibronectin 1st type III repeat; requisite roles for cell surface proteoglycans and integrins. BMC Cell Biol. 2, 18. 10.1186/1471-2121-2-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C., Kirsch K. H., Zhao Y., Jeay S., Palamakumbura A. H., Trackman P. C., et al. (2007). The tumor suppressor activity of the lysyl oxidase propeptide reverses the invasive phenotype of Her-2/neu-driven breast cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 1105–1112. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S., Hascall V. C., Markwald R. R., Ghatak S. (2015). Interactions between hyaluronan and its receptors (CD44, RHAMM) regulate the activities of inflammation and cancer. Front. Immunol. 6:201. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missan D. S., DiPersio M. (2012). Integrin control of tumor invasion. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 22, 309–324. 10.1615/CritRevEukarGeneExpr.v22.i4.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monboisse J. C., Oudart J. B., Ramont L., Brassart-Pasco S., Maquart F. X. (2014). Matrikines from basement membrane collagens: a new anti-cancer strategy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 2589–2598. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monslow J., Govindaraju P., Puré E. (2015). Hyaluronan - a functional and structural sweet spot in the tissue microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 6:231. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morbidelli L., Donnini S., Chillemi F., Giachetti A., Ziche M. (2003). Angiosuppressive and angiostimulatory effects exerted by synthetic partial sequences of endostatin. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 5358–5369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. R., Humphries M. J., Bass M. D. (2007). Synergistic control of cell adhesion by integrins and syndecans. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 957–969. 10.1038/nrm2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neskey D. M., Ambesi A., Pumiglia K. M., McKeown-Longo P. J. (2008). Endostatin and anastellin inhibit distinct aspects of the angiogenic process. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 27:61. 10.1186/1756-9966-27-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. M. B., Subramanian I. V., Xiao X., Ghosh G., Nguyen P., Kelekar A., et al. (2009). Endostatin induces autophagy in endothelial cells by modulating Beclin 1 and beta-catenin levels. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 3687–3698. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00722.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y., Zhang X., Wang X., Chen J. (2006). Preparation and stability of N-terminal mono-PEGylated recombinant human endostatin. Bioconjug. Chem. 17, 995–999. 10.1021/bc050355d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitovic D., Tzardi M., Berdiaki A., Tsatsakis A., Tzanakakis G. N. (2015). Cancer microenvironment and inflammation: role of hyaluronan. Front. Immunol. 6:169. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning T., Jiang M., Peng Q., Yan X., Lu Z.-J., Peng Y.-L., et al. (2012). Low-dose endostatin normalizes the structure and function of tumor vasculature and improves the delivery and anti-tumor efficacy of cytotoxic drugs in a lung cancer xenograft murine model. Thorac. Cancer 3, 229–238. 10.1111/j.1759-7714.2012.00111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto T., Mlakar L., Takihara T., Feghali-Bostwick C. (2015). An endostatin-derived peptide orally exerts anti-fibrotic activity in a murine pulmonary fibrosis model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 28, 1102–1105. 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström A., Shaik Z. P., Gullberg D., Krieg T., Eckes B., Zent R., et al. (2009). Role of tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in the mechanism of endorepellin angiostatic activity. Blood 114, 4897–4906. 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdener G. B., Bais M. V., Trackman P. C. (2015). Determination of cell uptake pathways for tumor inhibitor lysyl oxidase propeptide. Mol. Oncol. 10, 1–23. 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasco S., Monboisse J. C., Kieffer N. (2000). The alpha 3(IV)185-206 peptide from noncollagenous domain 1 of type IV collagen interacts with a novel binding site on the beta 3 subunit of integrin alpha Vbeta 3 and stimulates focal adhesion kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32999–33007. 10.1074/jbc.M005235200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedchenko V., Zent R., Hudson B. G. (2004). Alpha(v)beta3 and alpha(v)beta5 integrins bind both the proximal RGD site and non-RGD motifs within noncollagenous (NC1) domain of the alpha3 chain of type IV collagen: implication for the mechanism of endothelia cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2772–2780. 10.1074/jbc.M311901200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitclerc E., Boutaud A., Prestayko A., Xu J., Sado Y., Ninomiya Y., et al. (2000). New functions for non-collagenous domains of human collagen type IV. Novel integrin ligands inhibiting angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8051–8061. 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocza P., Süli-Vargha H., Darvas Z., Falus A. (2008). Locally generated VGVAPG and VAPG elastin-derived peptides amplify melanoma invasion via the galectin-3 receptor. Int. J. Cancer 122, 1972–1980. 10.1002/ijc.23296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poluzzi C., Casulli J., Goyal A., Mercer T. J., Neill T., Iozzo R. V. (2014). Endorepellin evokes autophagy in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 16114–16128. 10.1074/jbc.M114.556530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z., Hu J., Xu H., Wang W., Nie C., Wang X. (2013). Generation of antitumor peptides by connection of matrix metalloproteinase-9 peptide inhibitor to an endostatin fragment. Anticancer Drugs 24, 677–689. 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328361b7ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S., Medzhitov R. (2009). Toll-like receptors and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 57–63. 10.1038/nrc2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehn M., Veikkola T., Kukk-Valdre E., Nakamura H., Ilmonen M., Lombardo C., et al. (2001). Interaction of endostatin with integrins implicated in angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 1024–1029. 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S., Ballut L. (2011). Matricryptins derived from collagens and proteoglycans. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 16, 674–697. 10.2741/3712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S., Féraud O., Lortat-Jacob H., Rencurosi A., Fukai N., Dkhissi F., et al. (2004). Characterization of endostatin binding to heparin and heparan sulfate by surface plasmon resonance and molecular modeling: role of divalent cations. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2927–2936. 10.1074/jbc.M309868200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S., Salza R. (2014). Matricryptins and matrikines: biologically active fragments of the extracellular matrix. Exp. Dermatol. 23, 457–463. 10.1111/exd.12435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S., Vallet S. D. (2015). Proteases decode the extracellular matrix cryptome. Biochimie. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinet A., Fahem A., Cauchard J.-H., Huet E., Vincent L., Lorimier S., et al. (2005). Elastin-derived peptides enhance angiogenesis by promoting endothelial cell migration and tubulogenesis through upregulation of MT1-MMP. J. Cell Sci. 118, 343–356. 10.1242/jcs.01613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper J. A., Williamson R. C., Bass M. D. (2012). Syndecan and integrin interactomes: large complexes in small spaces. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 22, 583–590. 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosca E. V., Koskimaki J. E., Rivera C. G., Pandey N. B., Tamiz A. P., Popel A. S. (2011). Anti-angiogenic peptides for cancer therapeutics. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 12, 1101–1116. 10.2174/138920111796117300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R. (2008). VEGF receptor protein-tyrosine kinases: structure and regulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 375, 287–291. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salza R., Oudart J.-B., Ramont L., Maquart F.-X., Bakchine S., Thoannès H., et al. (2015). Endostatin level in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 44, 1253–1261. 10.3233/JAD-142544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salza R., Peysselon F., Chautard E., Faye C., Moschcovich L., Weiss T., et al. (2014). Extended interaction network of procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1 in the extracellular matrix. Biochem. J. 457, 137–149. 10.1042/BJ20130295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S., Hintermann E., Bilban M., Koshikawa N., Hojilla C., Khokha R., et al. (2003). Binding to EGF receptor of a laminin-5 EGF-like fragment liberated during MMP-dependent mammary gland involution. J. Cell Biol. 161, 197–209. 10.1083/jcb.200208145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Huang Y., Zhou H., Song X., Yuan S., Fu Y., et al. (2007). Nucleolin is a receptor that mediates antiangiogenic and antitumor activity of endostatin. Blood 110, 2899–2906. 10.1182/blood-2007-01-064428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S.-U., Cho H.-M., Merchan J., Zhang J., Kovacs K., Jing Y., et al. (2011). Targeted delivery of an antibody-mutant human endostatin fusion protein results in enhanced antitumor efficacy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 603–614. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M. (2012). An inside view: VEGF receptor trafficking and signaling. Physiology (Bethesda) 27, 213–222. 10.1152/physiol.00016.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M. A., Teixeira F. C. O. B., Fontes M., Arêas A. L., Leal M. G., Pavão M. S. G., et al. (2015). Heparan sulfate proteoglycans may promote or inhibit cancer progression by interacting with integrins and affecting cell migration. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:453801. 10.1155/2015/453801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N., Ding Y., Zhuo W., He T., Fu Z., Chen Y., et al. (2012). The nuclear translocation of endostatin is mediated by its receptor nucleolin in endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 15, 697–711. 10.1007/s10456-012-9284-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtmann A., Zarbock A. (2012). CXCR2: from bench to bedside. Front. Immunol. 3:263. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J., Stenbjorn R. S., Gorse K., Su K., Hauser K. F., Ricard-Blum S., et al. (2012). Target-derived matricryptins organize cerebellar synapse formation through α3β1 integrins. Cell Rep. 2, 223–230. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar A., Nyberg P., Keshamouni V. G., Mannam A. P., Li J., Sugimoto H., et al. (2005). Human alpha1 type IV collagen NC1 domain exhibits distinct antiangiogenic activity mediated by alpha1beta1 integrin. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2801–2810. 10.1172/JCI24813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Sudhakar A., Sugimoto H., Yang C., Lively J., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. (2003). Human tumstatin and human endostatin exhibit distinct antiangiogenic activities mediated by alpha v beta 3 and alpha 5 beta 1 integrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4766–4771. 10.1073/pnas.0730882100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Sund M., Nyberg P., Eikesdal H. P. (2010). Endogenous matrix-derived inhibitors of angiogenesis. Pharmaceuticals 3, 3021–3039. 10.3390/ph3103021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swindle C. S., Tran K. T., Johnson T. D., Banerjee P., Mayes A. M., Griffith L., et al. (2001). Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats of human tenascin-C as ligands for EGF receptor. J. Cell Biol. 154, 459–468. 10.1083/jcb.200103103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takafuji V., Forgues M., Unsworth E., Goldsmith P., Wang X. W. (2007). An osteopontin fragment is essential for tumor cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 26, 6361–6371. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H., Yang S., Liu C., Cao J., Mu G., Wang F. (2012). Enhanced anti-angiogenesis and anti-tumor activity of endostatin by chemical modification with polyethylene glycol and low molecular weight heparin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 66, 648–654. 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. R., Trowbridge J. M., Rudisill J. A., Termeer C. C., Simon J. C., Gallo R. L. (2004). Hyaluronan fragments stimulate endothelial recognition of injury through TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17079–17084. 10.1074/jbc.M310859200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro J. G., Parker A. E., Zhu X., Green M. R. (2006). p53-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis through up-regulation of a collagen prolyl hydroxylase. Science 313, 968–971. 10.1126/science.1126391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenard J., Ramont L., Mir L. M., Dupont-Deshorgue A., Maquart F.-X., Monboisse J.-C., et al. (2013). A new anti-tumor strategy based on in vivo tumstatin overexpression after plasmid electrotransfer in muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 432, 549–552. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolg C., McCarthy J. B., Yazdani A., Turley E. A. (2014). Hyaluronan and RHAMM in wound repair and the “cancerization” of stromal tissues. Biomed Res. Int. 2014:103923. 10.1155/2014/103923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y., Zhong K., Tian H., Gao X., Xu X., Yin X., et al. (2010). Characterization of a monoPEG20000-Endostar. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 46, 331–336. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole B. P. (2009). Hyaluronan-CD44 interactions in cancer: paradoxes and possibilities. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 7462–7468. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toupance S., Brassart B., Rabenoelina F., Ghoneim C., Vallar L., Polette M., et al. (2012). Elastin-derived peptides increase invasive capacities of lung cancer cells by post-transcriptional regulation of MMP-2 and uPA. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 29, 511–522. 10.1007/s10585-012-9467-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran M., Rousselle P., Nokelainen P., Tallapragada S., Nguyen N. T., Fincher E. F., et al. (2008). Targeting a tumor-specific laminin domain critical for human carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 68, 2885–2894. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugarte-Berzal E., Bailón E., Amigo-Jiménez I., Albar J. P., García-Marco J. A., García-Pardo A. (2014). A novel CD44-binding peptide from the pro-matrix metalloproteinase-9 hemopexin domain impairs adhesion and migration of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15340–15349. 10.1074/jbc.M114.559187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugarte-Berzal E., Bailón E., Amigo-Jiménez I., Vituri C. L., del Cerro M. H., Terol M. J., et al. (2012). A 17-residue sequence from the matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) hemopexin domain binds α4β1 integrin and inhibits MMP-9-induced functions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27601–27613. 10.1074/jbc.M112.354670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra M., Ransohoff R. M. (2012). Chemokine receptor CXCR2: physiology regulator and neuroinflammation controller? J. Neuroimmunol. 246, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R. K., Gunda V., Pawar S. C., Sudhakar Y. A. (2013). Extra cellular matrix derived metabolite regulates angiogenesis by FasL mediated apoptosis. PLoS ONE 8:e80555. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia A., Yang J. F., Huang Y.-H., Rosenblatt M. I., Chang J.-H., Azar D. T. (2015). Endostatin's emerging roles in angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, disease, and clinical applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1850, 2422–2438. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y.-Y., Tian G.-Y., Guo H.-S., Kang Y.-M., Yao Z.-H., Li X.-L., et al. (2013). Endostatin, an angiogenesis inhibitor, ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Respir. Res. 14:56. 10.1186/1465-9921-14-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Dong X., Xiu P., Zhong J., Wei H., Xu Z., et al. (2015a). T7 peptide inhibits angiogenesis via downregulation of angiopoietin-2 and autophagy. Oncol. Rep. 33, 675–684. 10.3892/or.2014.3653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Sun Y., Liu Y., Yu Q., Zhang Y., Li K., et al. (2005). Results of randomized, multicenter, double-blind phase III trial of rh-endostatin (YH-16) in treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Lung Cancer 8, 283–290. 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2005.04.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Lu X.-A., Liu P., Fu Y., Jia L., Zhan S., et al. (2015b). Endostatin has ATPase activity, which mediates its antiangiogenic and antitumor activities. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14, 1192–1201. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Chen P., Tang M., Li J., Pei Y., Cai S., et al. (2015c). Tumstatin 185-191 increases the sensitivity of non-small cell lung carcinoma cells to cisplatin by blocking proliferation, promoting apoptosis and inhibiting Akt activation. Am. J. Transl. Res. 7, 1332–1344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Bryan J., Franz C., Havlioglu N., Sandell L. J. (2010). Type IIB procollagen NH(2)-propeptide induces death of tumor cells via interaction with integrins alpha(V)beta(3) and alpha(V)beta(5). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20806–20817. 10.1074/jbc.M110.118521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Li Z., Wang Y., Cao D., Wang X., Jiang M., et al. (2015d). Versican silencing improves the antitumor efficacy of endostatin by alleviating its induced inflammatory and immunosuppressive changes in the tumor microenvironment. Oncol. Rep. 33, 2981–2991. 10.3892/or.2015.3903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]