Abstract

Background and objectives

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and abnormal left ventricular (LV) geometry predict adverse outcomes in the general and hypertensive populations, but findings in CKD are still inconclusive.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We enrolled 445 patients with hypertension and CKD stages 2–5 in two academic nephrology clinics in 1999–2003 who underwent both echocardiography and ambulatory BP monitoring. LVH (LV mass >100 g/m2 [women] and >131 g/m2 [men]) and relative wall thickness (RWT) were used to define LV geometry: no LVH and RWT≤0.45 (normal), no LVH and RWT>0.45 (remodeling), LVH and RWT≤0.45 (eccentric), and LVH and RWT>0.45 (concentric). We evaluated the prognostic role of LVH and LV geometry on cardiovascular (CV; composite of fatal and nonfatal events) and renal outcomes (composite of ESRD and all-cause death).

Results

Age was 64.1±13.8 years old; 19% had diabetes, and 22% had CV disease. eGFR was 39.9±20.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2. LVH was detected in 249 patients (56.0%); of these, 125 had concentric LVH, and 124 had eccentric pattern, whereas 71 patients had concentric remodeling. Age, women, anemia, and nocturnal hypertension were independently associated with both concentric and eccentric LVH, whereas diabetes and history of CV disease associated with eccentric LVH only, and CKD stages 4 and 5 associated with concentric LVH only. During follow-up (median, 5.9 years; range, 0.04–15.3), 188 renal deaths (112 ESRD) and 103 CV events (61 fatal) occurred. Using multivariable Cox analysis, concentric and eccentric LVH was associated with higher risk of CV outcomes (hazard ratio [HR], 2.59; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.39 to 4.84 and HR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.47 to 5.26, respectively). Similarly, greater risk of renal end point was detected in concentric (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.44 to 3.80) and eccentric (HR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.42 to 3.74) LVH. Sensitivity analysis using LVH and RWT separately showed that LVH but not RWT was associated with higher cardiorenal risk.

Conclusions

In patients with CKD, LVH is a strong predictor of the risk of poor CV and renal outcomes independent from LV geometry.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease; left ventricular geometry; blood pressure monitoring, ambulatory; echocardiography; female; follow-up studies; humans; hypertension; hypertrophy, left ventricular

Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is highly prevalent in the nondialysis CKD (ND-CKD) population from the early stages of renal disease (1–6), and increased left ventricular mass index (LVMI) represents one of the main risk factors responsible for the high incidence of cardiovascular (CV) disease and mortality in patients with CKD (7). Indeed, in patients with ND-CKD, LVH on electrocardiogram is associated with an absolute increase in CV mortality risk of 25 per 1000 person-years, which constitutes the largest increase among traditional risk factors (8). More recent studies have confirmed that LVH assessed by echocardiography heralds adverse CV and renal outcomes (6,9–11).

Routine echocardiographic examination frequently includes, other than LVMI, data on relative wall thickness (RWT) to identify different increased left ventricular (LV) geometric patterns (12). This information is clinically relevant, because according to studies in cohorts of the general population and patients with essential hypertension, abnormal patterns of LV geometry adversely affect prognosis, with higher risk of CV events and all-cause mortality particularly evident in patients with concentric LVH (13–16). Conversely, data on the prognostic role of altered LV geometry are scarce and inconclusive in patients with ND-CKD; the only two studies available in this setting have shown that concentric and eccentric LVH is associated with either more rapid progression to ESRD or higher CV risk, respectively (10,17). These previous studies assessed these end points separately and during a limited follow-up not >4 years (10,17).

This study evaluates a cohort of patients with ND-CKD managed in the tertiary care setting to assess the association of LVH and LV geometry with cardiorenal prognosis defined by the composite end point of fatal and nonfatal CV events and the composite end point of ESRD and all-cause death before ESRD. Secondary aim is to identify the clinical correlates of LV geometry, including ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), which is now considered the most reliable tool for assessing true BP load in the ND-CKD population (18–21). The identification of factors associated with higher risk of progression to ESRD or death should disclose opportunities for better clinical management, thus improving prognosis and optimizing health expenditure for CKD care (22,23).

Materials and Methods

This multicenter, prospective cohort study was carried out in two nephrology clinics in which, as a routine procedure, ABPM and echocardiography are obtained in all patients to obtain better risk stratification independent of the severity of disease. We enrolled consecutive adult patients with ND-CKD from January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2003 with concomitant ABPM and echocardiographic evaluation performed ≤30 days apart. Patients were included in this study if they had either an eGFR by the four–variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or GFR=60–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 plus proteinuria >0.3 g/24 h assessed in two occasions with an interval ≥3 months. Exclusion criteria were true normotension (presence of office and 24-hour BP <130/80 mmHg in the absence of antihypertensive therapy), changes in GFR>30% in the previous 3 months, changes in antihypertensive therapy 2 weeks before ABPM, atrial fibrillation, severe coronary heart disease associated with the presence of wall motion abnormality by two-dimensional echocardiography, left bundle branch block, severe valvular heart disease as assessed by clinical examination and echocardiography, and either inadequate ABPM (<20 and less than seven recordings during the day and night, respectively) (24) or poor-quality echocardiography. Medical history, laboratory data, and current therapy were collected during the initial visit. Institutional Review Boards of the participating centers approved the protocol, and informed consent was obtained from all patients before study enrolment.

Patients were always seen by the same nephrologist in either clinic. All patients were instructed to restrict dietary salt (<6 g NaCl per day) and protein (≤0.8 g/kg body wt per day) using personalized written regimens where appropriate. Antihypertensive medications were administered to achieve office BP <130/80 mmHg. Drugs were distributed from 8 ante meridian (a.m.) to 10 post meridian (p.m.); doses of furosemide ≥50 mg/d were divided in two administrations (8 a.m. and 8 p.m.).

BP and Echocardiographic Measurements

Office BP was measured in both centers during the physician’s visit in a sitting position three times at 5-minute intervals. Measurements were obtained by the same physicians, one for each center, who were not aware of the results of ABPM. Similar ABPM protocols (Spacelabs 90207) were used in the two participating clinics as previously specified (18,19) and according to the European Society of Hypertension (24). The monitor recorded BP every 15 minutes (7 a.m. to 11 p.m.) or every 30 minutes (11 p.m. to 7 a.m.). Daytime and nighttime periods were derived from the diaries recorded by the patients during monitoring. Daytime and nighttime BP goals were <135/85 and <120/70 mmHg, respectively (24).

Echocardiographic evaluation was obtained using standard M mode and two-dimensional images (Vivid 7 Dimension-GE Healthcare Ultrasound; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Images were digitally stored and analyzed by two independent experienced cardiologists. A random sample of images obtained in one center was sent to the other center to evaluate concordance of measurements. Offline analysis was obtained using the workstation Echopac PC’08 version 7.0.0 GE Vingmed Ultrasound (GE Healthcare). An average of three measurements was made for each variable. End diastolic left ventricular internal diameter (LVIDd), diastolic posterior wall thickness (PWTd), and diastolic septal wall thickness were measured according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography (25). LVMI (in grams per meter2) was calculated using the following equation (25): LVMI=[0.832× [(diastolic septal wall thickness + LVIDd + PWTd)3 − (LVIDd)3] ×0.6]/body surface area.

Patients’ Classification and Outcomes

Patients were classified as having LVH if they had LVMI>100 g/m2 in women and >131 g/m2 in men (17). RWT was measured at end diastole as 2PWTd/LVIDd and considered to be increased if >0.45 according to the study by Chen et al. (10) and the Cardiovascular Risk Reduction by Early Anemia Treatment with Epoetin β (CREATE) Study (17). LVH and RWT were used to categorize LV geometry: normal (no LVH and normal RWT), concentric remodeling (no LVH and increased RWT), eccentric hypertrophy (LVH and normal RWT), and concentric hypertrophy (LVH and increased RWT).

This etiologic study aimed at evaluating the role of LVH and LV geometry on the composite end point of fatal and nonfatal CV events, the composite end point of renal death defined as ESRD and all-cause mortality before ESRD (primary end points), and the single components of renal death (secondary end points). ESRD was reached on the day that chronic dialysis started. Death certificates and autopsy reports were used to adjudicate CV deaths on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Mofidication. Nonfatal CV events requiring hospitalization (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, revascularization, peripheral vascular disease, and nontraumatic amputation) were adjudicated on the basis of hospital records; in patients with multiple nonfatal CV events, we included in the analysis the one occurring first. Patients were followed until August 31, 2014, death before ESRD, or ESRD and censored on the date of the last clinic visit. Secondary outcome was to evaluate the clinical correlates of eccentric and concentric LVH.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as means±SDs or medians and interquartile ranges and compared by ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis H test, respectively. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and compared by chi-squared test. Demographic and clinical factors associated with LVH were evaluated by logistic regression, whereas factors associated to eccentric and concentric LVH were identified by multivariable nominal logistic regression. Because the four categories of LV geometry were not clearly ranked in severity, we dichotomized the outcome between normal and concentric remodeling (patients without LVH) versus concentric and eccentric LVH.

We analyzed time to renal and CV end points by using Kaplan–Meier survival curves compared by log-rank test among four patterns of LV geometry and according to the presence of either LVH or increased RWT. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratio (HR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of altered LV geometry adjusted for the effect of potentially confounding variables defined a priori and using as reference patients with normal geometry. Functional form of continuous covariates was assessed using cumulative sums of Martingale residuals. Proportional hazards assumptions were evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals tests. Additional multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to test association of LVH and increased RWT with outcomes; this analysis was performed with LVH and increased RWT included in the Cox regression model separately or simultaneously. Models, when nested, were compared using the likelihood ratio test. Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

Figure 1 depicts the flow diagram of the study. We classified 125 patients (28.1%; 95% CI, 23.9 to 32.3) with normal geometry, 71 (16.0%; 95% CI, 12.6 to 19.4) with concentric remodeling, 124 (27.9%; 95% CI, 23.7 to 32.0) with eccentric LVH, and 125 (28.1%; 95% CI, 23.9 to 32.3) with concentric LVH. The prevalence of eccentric and concentric LVH was higher among patients with more advanced CKD (Figure 2). Patients with eccentric and concentric LVH were older, were predominantly women, had a longer duration of hypertension, and had lower levels of eGFR, albumin, and hemoglobin (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort development diagram. ABPM, ambulatory BP monitoring.

Figure 2.

Higher prevalence of eccentric and concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in patients with lower eGFR. LV, left ventricular.

Table 1.

Basal demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

| Population Characteristic (n=445) | Normal Geometry | Concentric Remodeling | Eccentric LVH | Concentric LVH | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 125 | 71 | 124 | 125 | NA |

| Age, yr | 58.5±15.2 | 62.5±14.6 | 66.9±12.8 | 67.9±10.6 | <0.001 |

| Sex, % | 21.6 | 19.7 | 51.6 | 51.2 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 21.6 | 21.1 | 15.3 | 19.2 | 0.61 |

| Prior CV disease, % | 20.0 | 14.1 | 25.8 | 24.8 | 0.21 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.3±4.0 | 26.3±4.1 | 27.5±5.0 | 26.9±4.9 | 0.16 |

| Duration of hypertension, yr | 7 [3–14] | 7 [3–16] | 9 [4–15] | 11 [6–20] | 0.001 |

| Renal disease, % | 0.27 | ||||

| Hypertension | 46.4 | 38.0 | 41.9 | 48.8 | |

| GN | 15.2 | 19.7 | 28.2 | 20.8 | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 11.2 | 15.5 | 6.5 | 11.2 | |

| ADPKD | 8.8 | 5.6 | 4.0 | 4.8 | |

| Other/unknown | 18.4 | 21.1 | 19.4 | 14.4 | |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 47.8±20.0 | 41.7±20.3 | 36.3±19.7 | 34.5±18.2 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.3±2.0 | 12.8±1.7 | 12.0±1.8 | 11.9±2.0 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 203±51 | 204±44 | 202±53 | 199±44 | 0.88 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 3.98±0.51 | 3.80±0.55 | 3.74±0.53 | 3.80±0.53 | 0.004 |

| Proteinuria, g/d | 0.3 [0.1–1.2] | 0.3 [0.1–1.1] | 0.5 [0.1–1.6] | 0.4 [0.1–1.1] | 0.66 |

| UNaV, mmol/d | 161±72 | 163±75 | 153±73 | 160±58 | 0.90 |

Data are means±SDs, medians [interquartile ranges], or percentages. eGFR was by the four–variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation. LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; NA, not applicable; CV, cardiovascular; BMI, body mass index; ADPKD, autosomal polycystic kidney disease; UNaV, urinary sodium excretion.

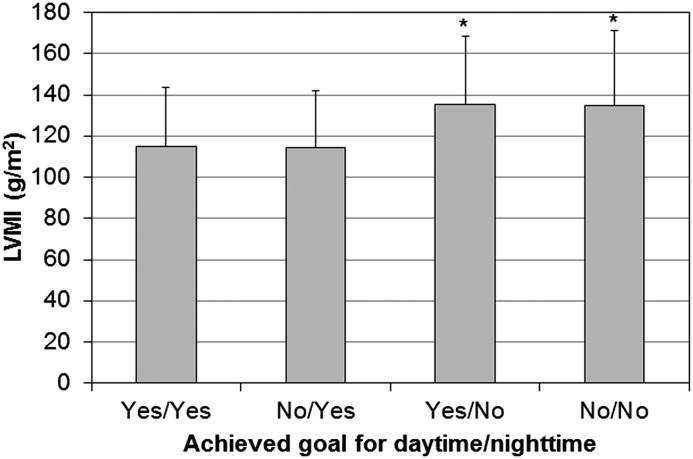

Echocardiographic and BP measurements are reported in Table 2. LVMI was lower in patients with eccentric LVH than in those with concentric LVH (P=0.02). Patients with LVH had a worse BP profile, with higher levels of daytime and nighttime systolic BP. Achievement of daytime goal (<135/85 mmHg) ranged from 48.4% to 59.2% and was similar among the four groups (P=0.29). In contrast, achievement of nighttime goal (<120/70 mmHg) was lower in patients with eccentric and concentric LVH (32.3% and 29.6%, respectively) compared with those with concentric remodeling (45.1%) and normal geometry (53.6%; P<0.001 for trend). Therefore, patients who did not reach nighttime BP goal had higher LVMI, regardless of whether daytime BP goal was achieved (Figure 3). Antihypertensive therapy did not differ among groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Office and ambulatory BP, echocardiographic parameters, and antihypertensive therapy at baseline

| Variable | Normal Geometry | Concentric Remodeling | Eccentric LVH | Concentric LVH | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office systolic BP, mmHg | 140±17 | 140±16 | 143±17 | 146±19 | 0.03 |

| Office diastolic BP, mmHg | 83±11 | 82±10 | 80±11 | 80±12 | 0.03 |

| 24-h Systolic BP, mmHg | 126±16 | 129±15 | 133±16 | 134±19 | 0.001 |

| 24-h Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76±11 | 75±10 | 75±11 | 75±13 | 0.69 |

| Daytime systolic BP, mmHg | 129±16 | 133±15 | 134±15 | 136±20 | 0.01 |

| Daytime diastolic BP, mmHg | 79±12 | 78±10 | 77±11 | 77±13 | 0.43 |

| Nighttime systolic BP, mmHg | 120±18 | 122±18 | 129±20 | 132±21 | <0.001 |

| Nighttime diastolic BP, mmHg | 70±13 | 69±11 | 71±12 | 71±14 | 0.87 |

| BP-lowering drugs, n | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | 0.92 |

| ACEI and/or ARB, % | 68.0 | 62.0 | 61.3 | 62.4 | 0.69 |

| Calcium channel blockers, % | 45.6 | 54.9 | 50.8 | 56.0 | 0.37 |

| β-Blockers, % | 25.6 | 16.9 | 29.0 | 32.0 | 0.13 |

| Diuretics, % | 37.6 | 29.6 | 41.9 | 36.8 | 0.40 |

| Left atrial diameter, cm | 3.91±0.43 | 3.75±0.33 | 4.09±0.62 | 3.95±0.55 | 0.01 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 62.2±7.1 | 62.4±6.6 | 58.2±8.6 | 61.6±8.0 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction ≤50%, % | 27.5 | 5.9 | 37.3 | 29.4 | 0.14 |

| Septal wall thickness, cm | 1.04±0.17 | 1.17±0.15 | 1.20±0.14 | 1.35±0.19 | NA |

| LV posterior wall, cm | 0.92±0.14 | 1.10±0.11 | 1.03±0.11 | 1.25±0.14 | NA |

| LV diastolic diameter, cm | 4.95±0.45 | 4.43±0.36 | 5.38±0.46 | 4.89±0.47 | NA |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.38±0.05 | 0.51±0.05 | 0.38±0.05 | 0.52±0.06 | NA |

| LV mass, g | 181±44 | 183±35 | 246±52 | 261±69 | NA |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 100±19 | 104±16 | 142±26 | 152±34 | NA |

Data are means±SDs or percentages. Nondippers are night-to-day ratios of systolic ambulatory BP ≥0.9. LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; ACEI, angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; NA, not applicable; LV, left ventricular.

Figure 3.

Left ventricular mass index (LVMI) in patients stratified according to achievement of goals for daytime BP (<135/85 mmHg) and nighttime BP (<120/70 mmHg). Data are means and SDs. *P<0.05 versus yes/yes and no/yes.

Multinomial regression analysis showed that age and women were associated with a greater risk of having both types of LVH (eccentric and concentric) (Table 3). A similar finding was observed with anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dl), which was associated with higher probability of eccentric and concentric LVH. Achievement of nighttime BP goal was linked to lower risk of having eccentric and concentric LVH by 67% and 56%, respectively, whereas achievement of daytime goal as well as office BP goal did not associate with LV geometry. Finally, diabetes and body mass index (BMI) were associated with greater odds of eccentric but not concentric LVH, whereas lower eGFR (<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2) was associated with concentric but not eccentric LVH (Table 3). Age, women, BMI, diabetes, anemia, lower eGFR, and nighttime BP goal also correlated with LVH independent of geometry (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlates of left ventricular hypertrophy by logistic regression analysis and correlates of eccentric or concentric left ventricular hypertrophy by multinomial logistic regression analysis

| Variable | LVH | Eccentric LVH | Concentric LVH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age, yr | 1.04 (1.03 to 1.06) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.07) | <0.001 |

| Women | 4.51 (2.77 to 7.35) | <0.001 | 4.74 (2.72 to 8.28) | <0.001 | 4.31 (2.48 to 7.49) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.15) | <0.01 | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19) | 0.002 | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.13) | 0.11 |

| Diabetes mellitus, yes versus no | 2.03 (1.09 to 3.80) | 0.03 | 2.78 (1.28 to 6.02) | 0.01 | 1.56 (0.77 to 3.17) | 0.22 |

| History of CVD, yes versus no | 1.61 (0.94 to 2.78) | 0.09 | 1.70 (0.91 to 3.16) | 0.10 | 1.54 (0.83 to 2.87) | 0.17 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||||

| >60 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 60–30 | 1.49 (0.79 to 2.81) | 0.22 | 1.12 (0.54 to 2.35) | 0.76 | 2.11 (0.92 to 4.82) | 0.08 |

| <30 | 2.08 (1.03 to 4.19) | 0.04 | 1.54 (0.68 to 3.46) | 0.30 | 2.96 (1.22 to 7.22) | 0.02 |

| Anemia, yes versus no | 2.38 (1.30 to 4.36) | <0.01 | 2.17 (1.10 to 4.31) | 0.03 | 2.58 (1.32 to 5.05) | <0.01 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 1.00 (0.63 to 1.59) | 0.99 | 0.85 (0.50 to 1.46) | 0.56 | 1.16 (0.67 to 1.99) | 0.60 |

| Office BP goal, yes versus no | 0.88 (0.46 to 1.67) | 0.68 | 0.99 (0.47 to 2.11) | 0.99 | 0.77 (0.36 to 1.66) | 0.51 |

| Daytime BP goal, yes versus no | 0.95 (0.55 to 1.65) | 0.86 | 0.96 (0.51 to 1.82) | 0.91 | 0.93 (0.49 to 1.76) | 0.83 |

| Nighttime BP goal, yes versus no | 0.38 (0.21 to 0.69) | 0.001 | 0.33 (0.17 to 0.65) | 0.001 | 0.44 (0.23 to 0.86) | 0.02 |

eGFR was by the four–variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <11 g/dl. Office BP goal is <130/80 mmHg. Daytime BP goal is <135/85 mmHg. Nighttime BP goal is <120/70 mmHg. LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Renal and CV Survival

During follow-up (median, 5.9 years; range, 0.04–15.3), we registered 188 renal deaths (112 patients required chronic dialysis and 76 died). The CV end point was registered in 103 patients (61 CV deaths and 42 nonfatal events). The incidence of renal and CV events was higher in patients with eccentric and concentric LVH (Figure 4). Multivariable Cox analysis confirmed that, compared with normal geometry, eccentric and concentric LVHs were both associated with a 2.6–2.8 times increase in risk of CV outcomes and a 2.3-fold greater risk of renal outcomes, whereas LV remodeling was not associated with any end point (Table 4). A similar risk association was detected between LV geometry and secondary end points (that is, ESRD and death) (Table 4).

Figure 4.

Global outcome was worse in patients with eccentric and concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Incidence of renal death (left panel) and fatal nonfatal cardiovascular (CV) events (right panel) in patients with normal geometry (thin line), concentric remodeling (thin dotted line), concentric LVH (bold line), and eccentric LVH (dotted bold line).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for primary outcomes (fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events and ESRD or death) and secondary outcomes (ESRD and all-cause death separately) in patients stratified according to left ventricular geometry

| LV Geometry | CV Outcomes | ESRD or Death | ESRD | All-Cause Death | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | |

| Normal geometry (n=125) | 15 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.6) | Reference | 31 | 3.3 (2.3 to 4.6) | Reference | 21 | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.4) | Reference | 10 | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | Reference |

| Concentric remodeling (n=71) | 11 | 2.3 (1.2 to 4.2) | 1.07 (0.49 to 2.35) | 15 | 2.9 (1.6 to 4.8) | 0.66 (0.35 to 1.25) | 11 | 1.9 (0.9 to 3.6) | 1.18 (0.53 to 2.63) | 4 | 1.0 (0.3 to 2.3) | 0.48 (0.15 to 1.55) |

| Eccentric LVH (n=124) | 36 | 6.0 (4.3 to 8.3) | 2.79 (1.47 to 5.26)b | 69 | 9.3 (7.3 to 11.8) | 2.30 (1.42 to 3.74)b | 42 | 5.7 (4.1 to 7.7) | 3.06 (1.58 to 5.90)b | 27 | 3.6 (2.4 to 5.2) | 2.32 (1.07 to 5.07)b |

| Concentric LVH (n=125) | 41 | 6.9 (4.9 to 9.4) | 2.59 (1.39 to 4.84)b | 73 | 10.4 (8.1 to 13.2) | 2.33 (1.44 to 3.80)b | 38 | 5.4 (3.8 to 7.4) | 2.91 (1.46 to 5.79)b | 35 | 5.1 (3.5 to 7.1) | 3.17 (1.50 to 6.71)b |

Event rate is expressed as event per 100 patient-years. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is defined as left ventricular (LV) mass index >100 g/m2 in women and >131 g/m2 in men. LVH and relative wall thickness (RWT) were used to define LV geometry: normal LV, no LVH and RWT≤0.45; LV remodeling, no LVH and RWT>0.45; eccentric LVH, LVH and RWT≤0.45; and concentric LVH, LVH and RWT>0.45. CV, cardiovascular; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Cox model is adjusted for age, sex, diabetes, history of CV disease, eGFR, hemoglobin, serum albumin, 24-hour proteinuria, and 24-hour systolic BP and stratified for center.

Significant HRs.

Because the risk of adverse outcomes in the four groups of LV geometry differed essentially because of LVH, we reran survival analysis including LVH and increased RWT separately. After adjusting for the confounders examined in the previous analysis, we confirmed that CV and renal risk were significantly associated with the presence of LVH, whereas RWT>0.45 did not influence outcomes (Table 5). No interaction was found between LVH and increased RWT for renal and CV outcomes (P=0.30 and P=0.45, respectively). The greater predictive role of LVH was confirmed by likelihood ratio test; specifically, adding LVH to increased RWT improved the model fit for renal death (P<0.001) and CV end point (P<0.001), whereas the model fit for both end points did not improve when increased RWT was added to LVH (P=0.45 and P=0.76, respectively).

Table 5.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for primary outcomes (fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events and ESRD or death) and secondary outcomes (ESRD and all-cause death separately) in patients stratified according to left ventricular hypertrophy and relative wall thickness

| Components of LV Geometry | CV Outcomes | ESRD or Death | ESRD | All-Cause Death | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Events (N) | Event Rate (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | |

| LVH | ||||||||||||

| Absent (n=196) | 26 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.7) | Reference | 46 | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.2) | Reference | 32 | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.1) | Reference | 14 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | Reference |

| Present (n=249) | 77 | 6.5 (5.1 to 8.1) | 2.61 (1.61 to 4.21)b | 142 | 9.8 (8.3 to 11.6) | 2.75 (1.87 to 4.06)b | 80 | 5.5 (4.4 to 6.9) | 2.79 (1.65 to 4.70)b | 62 | 4.3 (3.3 to 5.5) | 3.63 (1.95 to 6.77)b |

| RWT | ||||||||||||

| ≤0.45 (n=261) | 51 | 3.3 (2.5 to 4.3) | Reference | 101 | 5.9 (4.8 to 7.1) | Reference | 64 | 3.8 (2.9 to 4.8) | Reference | 37 | 2.1 (1.5 to 2.9) | Reference |

| >0.45 (n=184) | 52 | 4.9 (3.6 to 6.4) | 1.15 (0.78 to 1.71) | 87 | 7.2 (5.7 to 8.9) | 0.97 (0.72 to 1.30) | 48 | 3.9 (2.8 to 5.2) | 1.02 (0.68 to 1.52) | 39 | 3.3 (2.3 to 4.5) | 1.23 (0.78 to 1.95) |

Event rate is expressed as event per 100 patient-years. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is defined as left ventricular (LV) mass index >100 g/m2 in women and >131 g/m2 in men. CV, cardiovascular; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Cox model is adjusted for age, sex, diabetes, history of CV disease, eGFR, hemoglobin, serum albumin, 24-hour proteinuria, and 24-hour systolic BP and stratified for center.

Significant HRs.

A sensitivity analysis also including the patients with normotension (controlled BP in absence of antihypertensive therapy) confirmed results reported in Tables 3 and 4. The risk for adverse renal outcomes was higher in eccentric and concentric LVH (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.44 to 3.78 and HR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.46 to 3.82, respectively) as well as for CV events (HR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.49 to 5.31 and HR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.40 to 4.88 for eccentric and concentric LVH, respectively). Similarly, no association was found between increased RWT and risk of renal (0.96; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.28) or CV (1.16; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.72) events, whereas LVH portended a greater risk for adverse renal (2.74; 95% CI, 1.87 to 4.01) and CV (2.57; 95% CI, 1.60 to 4.12) outcomes.

Discussion

The association between increased LV mass and risk for adverse outcomes has been reported by other studies in patients with CKD (6,9–11). However, our study provides first-time evidence that, in patients with ND-CKD, the presence of LVH, independent of the different LV geometric pattern, portends a poor renal and CV long–term outcomes. In fact, both concentric and eccentric LVHs did associate with a two- to threefold increase in the risk of CV event, ESRD onset, and all-cause mortality.

Only two similar studies have been carried out in the ND-CKD population (10,17). A secondary analysis of the CREATE Study showed that both concentric and eccentric LVHs were associated with adverse CV outcomes, but no information was provided on renal outcomes (17). In contrast, our results differ from a prior study in an Asian cohort, where only concentric LVH had a significant effect on renal outcomes, with this being the only end point explored (10). Such a discrepancy can be explained by differences in race (all Asians patients), lower systolic and diastolic BP levels, and difference in the control group, which also included patients with concentric remodeling. Unfortunately, no additional differences could be detected, because the clinical characteristics of patients with concentric and eccentric LVH were not included in the report.

Our study highlights that LVH per se, rather than concentric or eccentric LVH, is the main predictor of cardiorenal prognosis. Indeed, when dissecting abnormal geometry in the two components used for defining it (that is, LVH and RWT), we found that LVH was the only factor associated to cardiorenal outcomes (Table 5). Previous studies in various non–CKD settings have reported contradicting results regarding the additional value provided by LV geometry (16,26,27). From the pathophysiologic standpoint, an increase in afterload (i.e., arterial hypertension or an increase in large arteries stiffness) can induce concentric LVH, whereas volume overload (i.e., anemia and hypervolemic states) leads to eccentric LVH (28). In patients with CKD, the simultaneous coexistence of all of these factors (hypertension, arterial stiffness, volume expansion, and anemia) may preclude the development of specific alterations in LV geometry because of an overlap of different hemodynamic stimuli. However, we cannot exclude that the selection of patients without severe coronary heart disease and dependent wall motion abnormality may have contributed to the lack of difference in the prognostic role of eccentric and concentric LVH.

In our cohort of patients with CKD managed in the nephrology tertiary care setting, the overall prevalence of LVH assessed by echocardiography was 56% overall and 61% in CKD stages 3–5. This prevalence is higher than that reported in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study (4,29) and the longitudinal changes of cardiac structure and function in chronic kidney disease (CASCADE) Study (5) (i.e., the two most recent available large cohort studies that have evaluated both the prevalence and the progression of cardiomyopathy in CKD). Furthermore, our cohort has a similar prevalence of concentric and eccentric LVH; however, concentric was the main geometric pattern in the CRIC Study (4), and eccentric was the most frequent abnormality in the CASCADE cohort (5). These differences may be likely ascribed to the greater prevalence in our cohort of ageing and CKD stages 4 and 5, both factors strictly associated with LVH (Table 3). Furthermore, the lower prevalence of LVH in the CASCADE cohort may be explained by race (all Asians patients) and the presence of lower BP levels and greater use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and β-blockers. These latter findings were also detected in the CRIC Study; however, there was a higher prevalence of diabetes and overweight/obesity, and 40% of the participants were black, an ethnic group peculiarly characterized by high incidence of LVH (30,31). All of these differences may also justify the discrepant result on the role of woman as a predictor of LVH. Indeed, in the CRIC Study, a nonsignificant 14% lower risk of having LVH was found in women (29), whereas we found that women were a strong predictor of LVH, which has been shown in previous observations (32,33). Additional possible explanations are related to the independent effect of BMI in women that has been reported to have a greater effect on LVH compared with in men (34,35). Indeed, in our cohort, BMI was greater in women than in men, with a twofold prevalence of obesity (data not shown).

Additional insights were attained by examining ABPM. Nighttime BP was identified as the main independent predictor of LVH and altered geometry (Table 3). This is a novel finding on the basis of the limited observations available so far in patients with CKD. Specifically, Wang et al. (36) found an association between LVH and 24-hour BP values but did not evaluate the role of daytime and nighttime BP. The association of LVH and nighttime BP has been previously reported in a single study limited to nondiabetic patients with advanced renal disease (37). Our results support previous observations from our group that nighttime BP is the main predictor of cardiorenal prognosis. Overall, the data from our previous study and this study indicate LVH as a potential mediator of adverse effect of nocturnal hypertension in patients with ND-CKD as previously shown in the non–CKD hypertensive population (38,39).

Some limitations have to be acknowledged in our study. First, only whites were examined. Second, echocardiographic measurements, although on the basis of evaluations of two independent observers, were not centralized. Third, we did not collect Doppler data, and we did not measure right-side parameters; therefore, we cannot evaluate a potential prognostic role of pulmonary hypertension on adverse outcomes as proposed by other investigators (40,41). By contrast, the strengths of this study include its multicenter nature, the nephrology tertiary care setting, the evaluation of patients with a wide range of eGFR, thus including both subjects in the early CKD stages and patients with more advanced renal failure, the assessment of both CV and renal outcomes, and the long follow-up.

The presence of LVH is a strong predictor of the risk of future adverse CV and renal outcomes in patients with CKD. Adding information on LV geometry does not enhance the stratification of cardiorenal risk. The strong association between LVH and nocturnal BP supports the role of nighttime BP load as the potential main determinant of LVH in patients with CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was endorsed by the Italian Society of Nephrology (Gruppo di Studio sul Trattamento Conservativo della Insufficienza Renale Cronica) without any financial support.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Paoletti E, Bellino D, Cassottana P, Rolla D, Cannella G: Left ventricular hypertrophy in nondiabetic predialysis CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 320–327, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Nicola L, Minutolo R, Chiodini P, Zoccali C, Castellino P, Donadio C, Strippoli M, Casino F, Giannattasio M, Petrarulo F, Virgilio M, Laraia E, Di Iorio BR, Savica V, Conte G, TArget Blood Pressure LEvels in Chronic Kidney Disease (TABLE in CKD) Study Group : Global approach to cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease: Reality and opportunities for intervention. Kidney Int 69: 538–545, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin A, Singer J, Thompson CR, Ross H, Lewis M: Prevalent left ventricular hypertrophy in the predialysis population: Identifying opportunities for intervention. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 347–354, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park M, Hsu CY, Li Y, Mishra RK, Keane M, Rosas SE, Dries D, Xie D, Chen J, He J, Anderson A, Go AS, Shlipak MG, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group : Associations between kidney function and subclinical cardiac abnormalities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1725–1734, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai QZ, Lu XZ, Lu Y, Wang AY: Longitudinal changes of cardiac structure and function in CKD (CASCADE study). J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1599–1608, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson GE, de Backer T, Contreras G, Wang X, Kendrick C, Greene T, Appel LJ, Randall OS, Lea J, Smogorzewski M, Vagaonescu T, Phillips RA, African American Study of Kidney Disease Investigators : Relationship of left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic function with cardiovascular and renal outcomes in African Americans with hypertensive chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 62: 518–525, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levey AS, Beto JA, Coronado BE, Eknoyan G, Foley RN, Kasiske BL, Klag MJ, Mailloux LU, Manske CL, Meyer KB, Parfrey PS, Pfeffer MA, Wenger NK, Wilson PW, Wright JT, Jr.: Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: What do we know? What do we need to learn? Where do we go from here? National Kidney Foundation Task Force on Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 853–906, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Cushman M, Manolio TA, Peterson D, Stehman-Breen C, Bleyer A, Newman A, Siscovick D, Psaty B: Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: Comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. JAMA 293: 1737–1745, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paoletti E, Bellino D, Gallina AM, Amidone M, Cassottana P, Cannella G: Is left ventricular hypertrophy a powerful predictor of progression to dialysis in chronic kidney disease? Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 670–677, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SC, Su HM, Hung CC, Chang JM, Liu WC, Tsai JC, Lin MY, Hwang SJ, Chen HC: Echocardiographic parameters are independently associated with rate of renal function decline and progression to dialysis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2750–2758, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SC, Chang JM, Liu WC, Huang JC, Tsai JC, Lin MY, Su HM, Hwang SJ, Chen HC: Echocardiographic parameters are independently associated with increased cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1064–1070, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganau A, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, de Simone G, Pickering TG, Saba PS, Vargiu P, Simongini I, Laragh JH: Patterns of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometric remodeling in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 19: 1550–1558, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krumholz HM, Larson M, Levy D: Prognosis of left ventricular geometric patterns in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 25: 879–884, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieb W, Gona P, Larson MG, Aragam J, Zile MR, Cheng S, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS: The natural history of left ventricular geometry in the community: Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of change in LV geometric pattern. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7: 870–878, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerdts E, Cramariuc D, de Simone G, Wachtell K, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB: Impact of left ventricular geometry on prognosis in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy (the LIFE study). Eur J Echocardiogr 9: 809–815, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muiesan ML, Salvetti M, Monteduro C, Bonzi B, Paini A, Viola S, Poisa P, Rizzoni D, Castellano M, Agabiti-Rosei E: Left ventricular concentric geometry during treatment adversely affects cardiovascular prognosis in hypertensive patients. Hypertension 43: 731–738, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckardt KU, Scherhag A, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, Clyne N, Locatelli F, Zaug MF, Burger HU, Drueke TB: Left ventricular geometry predicts cardiovascular outcomes associated with anemia correction in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2651–2660, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minutolo R, Agarwal R, Borrelli S, Chiodini P, Bellizzi V, Nappi F, Cianciaruso B, Zamboli P, Conte G, Gabbai FB, De Nicola L: Prognostic role of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in patients with nondialysis chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 171: 1090–1098, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minutolo R, Gabbai FB, Agarwal R, Chiodini P, Borrelli S, Bellizzi V, Nappi F, Stanzione G, Conte G, De Nicola L: Assessment of achieved clinic and ambulatory blood pressure recordings and outcomes during treatment in hypertensive patients with CKD: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 744–752, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ: Prognostic importance of ambulatory blood pressure recordings in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 69: 1175–1180, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabbai FB, Rahman M, Hu B, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Contreras G, Faulkner ML, Hiremath L, Jamerson KA, Lea JP, Lipkowitz MS, Pogue VA, Rostand SG, Smogorzewski MJ, Wright JT, Greene T, Gassman J, Wang X, Phillips RA, African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Study Group : Relationship between ambulatory BP and clinical outcomes in patients with hypertensive CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1770–1776, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taal MW, Brenner BM: Renal risk scores: Progress and prospects. Kidney Int 73: 1216–1219, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honeycutt AA, Segel JE, Zhuo X, Hoerger TJ, Imai K, Williams D: Medical costs of CKD in the Medicare population. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1478–1483, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, Clement D, de la Sierra A, de Leeuw P, Dolan E, Fagard R, Graves J, Head GA, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Mallion JM, Mancia G, Mengden T, Myers M, Ogedegbe G, Ohkubo T, Omboni S, Palatini P, Redon J, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, vanMontfrans G, Verdecchia P, Waeber B, Wang J, Zanchetti A, Zhang Y, European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring : European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens 31: 1731–1768, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ, Chamber Quantification Writing Group. American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee. European Association of Echocardiography : Recommendations for chamber quantification: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 18: 1440–1463, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Battistelli M, Bartoccini C, Santucci A, Santucci C, Reboldi G, Porcellati C: Adverse prognostic significance of concentric remodeling of the left ventricle in hypertensive patients with normal left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol 25: 871–878, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Simone G, Izzo R, Chinali M, De Marco M, Casalnuovo G, Rozza F, Girfoglio D, Iovino GL, Trimarco B, De Luca N: Does information on systolic and diastolic function improve prediction of a cardiovascular event by left ventricular hypertrophy in arterial hypertension? Hypertension 56: 99–104, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colucci WS, Braunwald E: Pathophysiology of heart failure. In: Heart Disease. A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 6th Ed., edited by Braunwald E, Zipes DP, Libby P, Philadelphia, WB Saunders Company, 2001, pp 503–533 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ricardo AC, Lash JP, Fischer MJ, Lora CM, Budoff M, Keane MG, Kusek JW, Martinez M, Nessel L, Stamos T, Ojo A, Rahman M, Soliman EZ, Yang W, Feldman HI, Go AS, CRIC and HCRIC Investigators : Cardiovascular disease among hispanics and non-hispanics in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2121–2131, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kizer JR, Arnett DK, Bella JN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Province MA, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Liu JE, Devereux RB: Differences in left ventricular structure between black and white hypertensive adults: The Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. Hypertension 43: 1182–1188, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drazner MH, Dries DL, Peshock RM, Cooper RS, Klassen C, Kazi F, Willett D, Victor RG: Left ventricular hypertrophy is more prevalent in blacks than whites in the general population: The Dallas Heart Study. Hypertension 46: 124–129, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerdts E, Okin PM, de Simone G, Cramariuc D, Wachtell K, Boman K, Devereux RB: Gender differences in left ventricular structure and function during antihypertensive treatment: The Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study. Hypertension 51: 1109–1114, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitta K, Iimuro S, Imai E, Matsuo S, Makino H, Akizawa T, Watanabe T, Ohashi Y, Hishida A: Risk factors for increased left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 17: 730–742, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Marcus R, Krause L, Weder AB, Dominguez-Meja A, Schork NJ, Julius S: Sex-specific determinants of increased left ventricular mass in the Tecumseh Blood Pressure Study. Circulation 90: 928–936, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Simone G, Devereux RB, Chinali M, Roman MJ, Barac A, Panza JA, Lee ET, Howard BV: Sex differences in obesity-related changes in left ventricular morphology: The Strong Heart Study. J Hypertens 29: 1431–1438, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Gong WY, Zhang J, Peng H, Tang H, Liu X, Ye ZC, Lou T: Disparate assessment of clinic blood pressure and ambulatory blood pressure in differently aged patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol 183: 54–62, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker B, Fabbian F, Giles M, Thuraisingham RC, Raine AE, Baker LR: Left ventricular hypertrophy and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 724–728, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuspidi C, Giudici V, Negri F, Sala C: Nocturnal nondipping and left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: An updated review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 8: 781–792, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuspidi C, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Sala C, Negri F, Grassi G, Mancia G: Nighttime blood pressure and new-onset left ventricular hypertrophy: Findings from the Pamela population. Hypertension 62: 78–84, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navaneethan SD, Wehbe E, Heresi GA, Gaur V, Minai OA, Arrigain S, Nally JV, Jr., Schold JD, Rahman M, Dweik RA: Presence and outcomes of kidney disease in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 855–863, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolignano D, Lennartz S, Leonardis D, D’Arrigo G, Tripepi R, Emrich IE, Mallamaci F, Fliser D, Heine G, Zoccali C: High estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in stage 2-4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 88: 130–136, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]