Abstract

Background and objectives

The broader use of combined expanded criteria donor and donation after circulatory death (ECD/DCD) kidneys may help expand the deceased donor pool. The purpose of our study was to evaluate discard rates of kidneys from ECD/DCD donors and factors associated with discard.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

ECD/DCD donors and kidneys were evaluated from January 1, 2000 to March 31, 2011 using data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. The kidney donor risk index was calculated for all ECD/DCD kidneys. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine risk factors for discarding both donor kidneys. The Kaplan–Meier product limit method and the log-rank statistic were used to assess the cumulative probability of graft failure for transplants from ECD/DCD donors where the mate kidney was discarded versus both kidneys were used.

Results

There were 896 ECD/DCD donors comprising 1792 kidneys. Both kidneys were discarded in 44.5% of donors, whereas 51.0% of all available kidneys were discarded. The kidney donor risk index scores were higher among donors of discarded versus transplanted kidneys (median, 1.82; interquartile range, 1.60, 2.07 versus median, 1.67; interquartile range, 1.49, 1.87, respectively; P<0.001); however, the distributions showed considerable overlap. The adjusted odds ratios for discard were higher among donors who were older, diabetic, AB blood type, and hepatitis C positive. The cumulative probabilities of total graft failure at 1, 3, and 5 years were 17.3%, 36.5%, and 55.4% versus 13.8%, 24.7%, and 40.5% among kidneys from donors where only one versus both kidneys were transplanted, respectively (log rank P=0.04).

Conclusions

Our study shows a significantly higher discard rate for ECD/DCD kidneys versus prior reports. Some discarded ECD/DCD kidneys may be acceptable for transplantation. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the factors that influence decision making around the use of ECD/DCD kidneys.

Keywords: epidemiology and outcomes, kidney transplantation, cadaver organ transplantation, expanded criteria donor, donation after circulatory death, kidney, registries, risk factors, tissue donors, transplant recipients

Introduction

Kidney transplantation is the RRT of choice for patients with ESRD (1,2). Because of the shortage of transplantable organs, strategies, such as the use of kidneys from expanded criteria donors (ECDs) and donation after circulatory death (DCD), have been pursued to increase the deceased donor pool (3–5). Because more ECD and DCD kidney transplants are performed over time, the availability of kidneys that fulfill both ECD and DCD criteria (i.e., ECD/DCD kidneys) is likely to increase as well.

Selection of kidneys for transplantation requires careful consideration of the risks and benefits to potential recipients. As a result of this process, clinicians may discard kidneys deemed to be inappropriate for transplantation (6). In a previous study by our group, we evaluated the kidney donor risk index (KDRI) of ECD and/or DCD kidneys in a cohort of recipients of deceased donor kidney transplants (7). The KDRI is a continuous score that uses donor and transplant characteristics assessed at the time of transplantation to estimate the future risk of graft failure (i.e., higher KDRI indicates a higher risk of graft failure) (8). When we compared the KDRIs of all subgroups of ECD and/or DCD kidneys (including combined ECD/DCD kidneys), we found considerable overlap in their distributions. However, some clinicians may perceive the risk of using combined ECD/DCD kidneys as unacceptably high, resulting in the discard of ECD/DCD kidneys that may have been transplantable.

In this era of kidney transplantation, where organ demand continues to exceed supply, discarding potentially transplantable kidneys is of significant consequence to patients and the health care system (9,10). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the discard rate and the determinants of discard of ECD/DCD kidneys. We hypothesize that a significant proportion of ECD/DCD kidneys will be discarded. Furthermore, we hypothesize that an appreciable number of these discarded kidneys may be suitable for transplantation as reflected by their donor characteristics and KDRIs.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cohort study of all ECD/DCD donors (i.e., deceased donors who fulfill the criteria for both ECD and DCD) recovered between January 1, 2000 and March 31, 2011 using data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR defines a deceased donor as a person from whom at least one organ is recovered for the purpose of transplantation. Donors from whom the KDRI could not be calculated because of missing data were excluded from the study.

The outcome of interest was the discard of both kidneys from ECD/DCD donors. Discard was defined as recovery of kidneys from a donor with subsequent nonuse of both kidneys or no attempt to recover the kidneys from a donor where at least one nonkidney organ was procured. Thus, scenarios where one ECD/DCD kidney was discarded and the other was transplanted were not considered to have the outcome of discard in this study. From the donor perspective, at least one clinician deemed kidneys from these donors suitable for transplantation. For descriptive purposes, the proportion of kidneys discarded from all ECD/DCD donors was also ascertained.

To evaluate the outcomes of transplanted ECD/DCD kidneys, we used the Kaplan–Meier product limit method to construct survival curves for total graft failure in patients receiving a kidney from a donor whose other kidney was discarded. In addition, we used the same method to evaluate the outcomes of kidneys from donors where both kidneys were used for transplantation. Total graft failure was defined as the need for chronic dialysis, pre-emptive retransplantation, or death with graft function.

Donor characteristics and the KDRIs of transplanted versus discarded ECD/DCD kidneys were compared using parametric and nonparametric tests as appropriate. Among donors from whom both kidneys were discarded, the transplant factors in the KDRI were set to the referent donor (i.e., cold ischemia time of 20 hours, one HLA-B mismatch, two HLA-DR mismatches, single-kidney transplant, and not en bloc transplantation). A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to determine risk factors for discarding both kidneys from ECD/DCD donors. The following donor variables were included in the multivariable model: age, sex, race, cause of death, presence of hypertension, presence of diabetes, terminal serum creatinine, height, weight, blood type, presence of renal biopsy, pulsatile machine perfusion (PMP) use, heavy alcohol use (defined as greater than two drinks per day), and hepatitis B core or hepatitis C antibody positivity. Additional analyses were conducted to account for clustering of outcomes within transplant centers by calculating robust SEMs for model–based parameter estimates.

In our primary analyses, we included donors with both kidneys recovered for transplantation and subsequently discarded as well as donors with both kidneys not used because of nonrecovery. We felt that the decision to not recover kidneys for transplantation when another organ from the same donor was recovered is noteworthy because kidneys are among the most commonly recovered organs. As a result, we included these donors in our primary analyses. However, as a sensitivity analysis, we refitted the models after excluding donors from whom neither kidney was recovered for transplantation.

A two–sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 13.1 (StataCorp., College Station, TX). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University Health Network.

Results

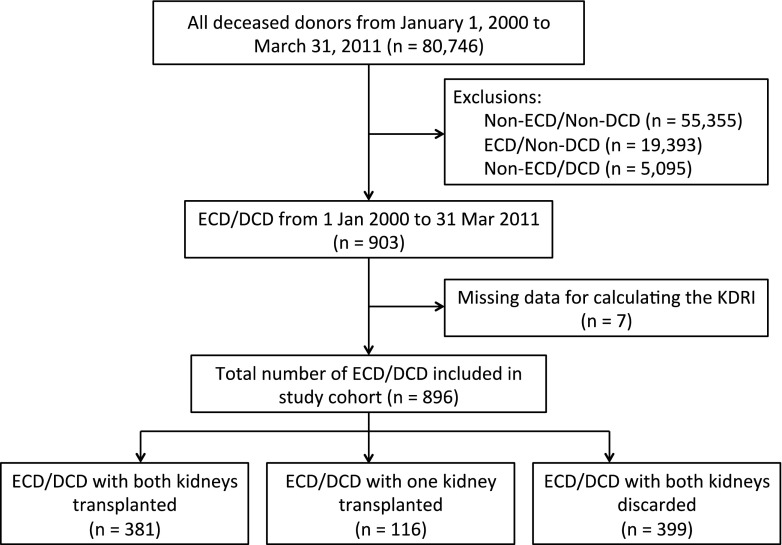

There were 903 donors of ECD/DCD kidneys eligible for study inclusion (Figure 1). After excluding seven donors with data missing to calculate the KDRI, the final cohort consisted of 896 deceased donors (497 had one or both kidneys transplanted, and 399 had both kidneys discarded). The prevalence of both kidneys being discarded from a given donor was 44.5% (399 of 896). This translated to 914 of 1792 ECD/DCD kidneys being discarded (51.0%). Discard rates differed slightly by transplant era, with a rate of 52.9% from 2000 to 2006 and 49.3% from 2007 to 2011.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. DCD, donation after circulatory death; ECD, expanded criteria donor; KDRI, kidney donor risk index.

The characteristics of the ECD/DCD kidney donors are shown in Table 1. The characteristics of donors from whom at least one kidney was transplanted were similar to donors from whom both kidneys were discarded, with the exception of a higher prevalence of diabetes and positivity for hepatitis B and/or C among donors who had both kidneys discarded. The median preterminal serum creatinine was also slightly higher among donors with both kidneys discarded. The presence of a renal biopsy and the use of PMP were more common among donors with at least one kidney transplanted.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of deceased donors of transplanted and discarded expanded criteria donor and donation after circulatory death kidneys

| Donor Characteristics | Both Kidneys Transplanted (n=381) | One Kidney Transplanted (n=116) | Both Kidneys Discarded (n=399) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean±SD | 59±5.3 | 60±5.8 | 59.7±5.9 | 0.12 |

| Women, % | 43.3 | 37.1 | 40.1 | 0.43 |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 89 | 84.5 | 84.2 | 0.12 |

| Black | 4.7 | 4.3 | 8.3 | |

| Hispanic | 3.4 | 6.9 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 2.9 | 4.3 | 2 | |

| Cause of death, % | ||||

| Anoxia | 21.3 | 25.9 | 24.8 | 0.21 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 63 | 55.2 | 59.7 | |

| Head trauma | 11.6 | 14.7 | 8.8 | |

| Other | 4.2 | 4.3 | 6.8 | |

| Hypertension, % | 74 | 79.3 | 74.4 | 0.50 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 12.9 | 15.5 | 28.6 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) | <0.001 |

| Body height (cm), median (IQR) | 170.2 (165.1, 180.0) | 171.5 (162.6, 177.8) | 172.7 (165, 178) | 0.83 |

| Body weight (kg), median (IQR) | 85.5 (74.0, 102.1) | 82.5 (70, 98) | 85 (71.0, 99.8) | 0.47 |

| Blood type, % | ||||

| A | 36.8 | 34.5 | 40.9 | 0.18 |

| B | 11.6 | 10.3 | 10 | |

| AB | 1.8 | 5.2 | 4.8 | |

| O | 49.9 | 50 | 44.4 | |

| Hepatitis C antibody positivity, % | 0.8 | 3.5 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Hepatitis B core antibody positivity, % | 2.9 | 6 | 6.3 | 0.002 |

| Renal biopsy, % | 94 | 97.4 | 75.7 | <0.001 |

| Pulsatile machine perfusion use, % | 79 | 80.2 | 39.9 | <0.001 |

| Heavy alcohol use | 16.8 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 0.21 |

IQR, interquartile range.

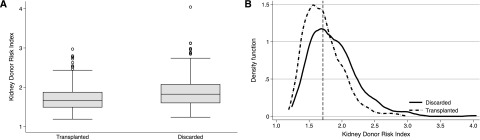

Figure 2 shows the KDRI distribution among donors with both kidneys discarded versus at least one kidney transplanted. Median (interquartile range [IQR]) KDRI was slightly higher among donors with both kidneys discarded compared with donors with at least one kidney transplanted (1.82; IQR, 1.60, 2.07 versus 1.67; IQR, 1.49, 1.87; P<0.001). However, the KDRI distributions of these two groups showed considerable overlap (Figure 2A). Among 399 donors with both kidneys discarded, 152 had KDRI scores that were below the median KDRI value of donors with at least one kidney transplanted (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Box plots and kernal density plots demonstrating significant overlap in kidney donor risk index scores in donors of transplanted and discarded kidneys. (A) Box plots of kidney donor risk index scores among donors of discarded and transplanted expanded criteria donor and donation after circulatory death (ECD/DCD) kidneys. (B) Kernel density plot of kidney donor risk index scores from donors of discarded ECD/DCD kidneys (solid line) and donors of transplanted ECD/DCD kidneys (dashed line); the vertical dashed line represents the median kidney donor risk index of donors of transplanted kidneys.

The results of the multivariable logistic regression model evaluating risk factors for discarding both ECD/DCD kidneys from the same donor are shown in Table 2. The adjusted relative odds of discard were higher among donors who were older, diabetic, blood type AB, and hepatitis C positive. A higher preterminal serum creatinine was also associated with higher odds of discard. However, the presence of a renal biopsy and PMP use were associated with lower odds of discard. Other factors, such as donor race, death by cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, and body height or weight, were not associated with higher odds of discard. The results of the multivariable logistic regression model accounting for clustering by transplant center were similar to the primary analyses, as was an analysis that excluded 56 donors with neither kidney recovered for transplantation (data not shown).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for discard by donor characteristics from a multivariable logistic regression model

| Donor Characteristics | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.09) | 0.003 |

| Men | 0.93 (0.60 to 1.45) | 0.86 |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | |

| Black | 1.23 (0.61 to 2.50) | 0.55 |

| Hispanic | 0.87 (0.40 to 1.95) | 0.74 |

| Other | 0.62 (0.23 to 1.65) | 0.34 |

| Cause of death, % | ||

| Anoxia | Reference | |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.29 (0.86 to 1.95) | 0.22 |

| Head trauma | 0.97 (0.54 to 1.73) | 0.91 |

| Other | 2.26 (1.08 to 4.70) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 1.03 (0.70 to 1.52) | 0.89 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.96 (1.30 to 2.97) | 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 3.13 (2.22 to 4.42) | <0.001 |

| Body height, cm | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.81 |

| Body weight, kg | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.55 |

| Blood type | ||

| O | Reference | |

| B | 1.23 (0.73 to 2.10) | 0.43 |

| AB | 2.88 (1.27 to 6.53) | 0.01 |

| A | 1.23 (0.88 to 1.72) | 0.24 |

| Hepatitis C antibody positivity | 3.43 (1.16 to 10.11) | 0.03 |

| Hepatitis B core antibody positivity | 1.67 (0.70 to 3.57) | 0.19 |

| Renal biopsy | 0.52 (0.30 to 0.91) | 0.02 |

| Pulsatile machine perfusion use | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.30) | <0.001 |

| Heavy alcohol use | 0.95 (0.59 to 1.51) | 0.82 |

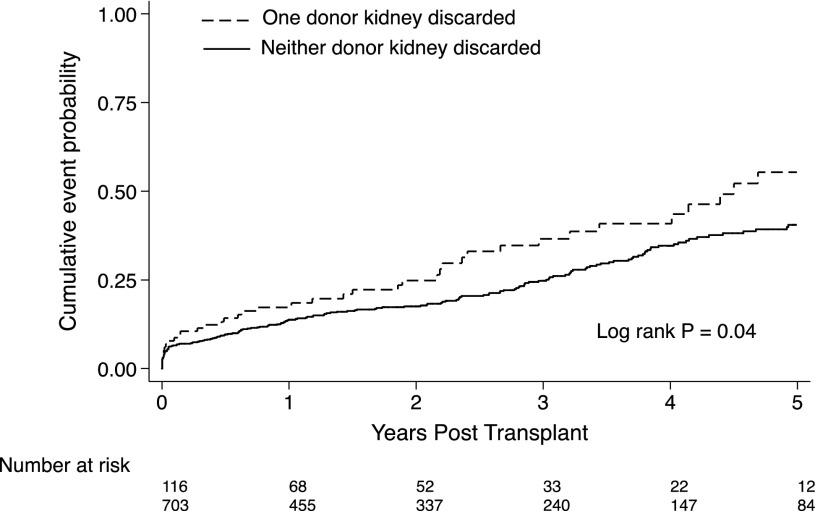

Among 497 donors of ECD/DCD kidneys from whom at least one kidney was transplanted, there were 116 donors where only one kidney was recovered and transplanted. Six recipients had graft failure (all of them caused by primary nonfunction), and 35 recipients died with graft function over 256.2 person-years of follow-up. The remaining 75 recipients were alive with a functioning graft at the end of study follow-up. From 381 donors with both ECD/DCD kidneys transplanted, there was a total of 703 recipients; 56 of these recipients received dual kidney transplants (i.e., two kidneys into one recipient). There were 32 recipients who developed graft failure, 23 (71.8%) of which were from primary nonfunction, and 154 recipients who died with graft function over 1682.5 person-years of follow-up. The cumulative probabilities of total graft failure at 1, 3, and 5 years post-transplant were 17.3%, 36.5%, and 55.4%, respectively, among kidneys from donors with only one kidney used and 13.8%, 24.7% and 40.5%%, respectively, among kidneys from donors with both kidneys used (log rank P=0.04) (Figure 3). Kaplan–Meier survival curves for death–censored graft failure and death with graft function are shown in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

The cumulative probabilities of total graft failure are higher among kidneys from donors where only one kidney was used compared to donors where both kidneys were used for transplantation. Kaplan–Meier curves for total graft failure among recipients of expanded criteria donor and donation after circulatory death kidneys from deceased donors where neither versus one kidney was discarded.

Discussion

The results of our study show that a significant proportion of kidneys from ECD/DCD donors are discarded. The observed discard rate of 51.0% among ECD/DCD kidneys is higher than that of ECD/non–DCD kidneys (32.0%–42.5%) and non–ECD/non–DCD kidneys (28.4%) in the modern era of kidney transplantation (6,11–13). Kidneys not recovered for transplantation are commonly excluded when calculating discard rates in other studies. Excluding these ECD/DCD kidneys in our study led to a discard rate of 47.7%, which remains higher than the rate published in the literature. As expected, several donor characteristics known to be associated with a higher risk of graft failure or adverse recipient outcomes were associated with higher odds of discard. However, other important donor characteristics also associated with an increased risk of graft failure (e.g., presence of hypertension, weight, death by cerebrovascular accident, and black race) were not associated with higher odds of discard. Furthermore, a significant overlap in KDRI distributions was observed between donors of transplanted and discarded kidneys. These findings suggest that a number of discarded ECD/DCD kidneys had similar KDRI profiles to many of the ECD/DCD kidneys that were transplanted.

In addition to the significant overlap of KDRI distributions, we found that 38% of donors of discarded kidneys had KDRI scores that fell below the median KDRI value of donors from whom at least one kidney was transplanted. These results suggest that some clinicians are opting to discard kidneys that other clinicians are willing to use. The identification of a suitable kidney for transplantation remains challenging because of the broad spectrum of risk that exists among ECD kidneys (14). We suspect that some clinicians will discard ECD/DCD kidneys primarily on the basis of the perception that the concomitant ECD/DCD insults will result in an unacceptable risk of graft failure for recipients of these kidneys.

Several studies have evaluated the outcomes of ECD/DCD kidneys. A retrospective study of deceased donor kidney transplants in the United Kingdom evaluated the effect of donor age on the risk of graft failure (15). Not surprisingly, donor age was associated with an increased risk of graft failure. However, the effect of donor age on graft survival was not substantially greater in DCD versus non–DCD kidney transplants. Similarly, Locke et al. (16) showed that donor age was associated with an increased risk of graft failure. However, the graft survival of recipients of ECD kidneys versus DCD kidneys from donors >50 years of age was similar. Previous work from our group evaluated the short- and long-term outcomes of ECD/DCD kidneys using the SRTR (7). Although DCD kidneys had a slightly increased risk of graft failure versus non–DCD kidneys, the relative hazard was not significantly greater in ECD versus non–ECD kidneys. Moreover, there was no significant increase in the relative hazard for graft failure of DCD versus non–DCD kidneys across a spectrum of KDRI scores. The results of these studies suggest that, when carefully selected, ECD/DCD kidneys may be appropriate for transplantation.

Our findings likely represent the variation in thresholds of acceptable risk among transplant clinicians and their respective transplant centers. Variation in discard rates on the basis of donor service area has been well documented among ECD kidneys, and our study suggests that this variation in practice likely persists when clinicians are faced with an ECD/DCD kidney offer (6). Also, in keeping with existing studies, the use of PMP was associated with significantly lower odds of discard in our study (6). However, it is unclear whether the use of PMP was a determining factor in the decision to accept an ECD/DCD kidney for transplantation or whether this represented the variation in PMP use across the United States. The presence of a kidney biopsy was also associated with lower odds of discard. However, the vast majority of biopsy results were unavailable in this study, and thus, it is difficult to make any inferences about the effect of kidney biopsies on the decision-making process. Finally, our study suggests that the decision to discard an ECD/DCD kidney is likely made in the context of the composition of the waiting list. In our study, kidneys from blood group AB donors were more likely to be discarded, which we hypothesize is because of the shorter waiting times for blood group AB deceased donor kidneys (3). In these instances, clinicians may be more likely to decline ECD/DCD kidneys with the expectation that a higher-quality kidney will become available in the near future.

In this study, there were 116 donors with one kidney discarded and the other transplanted. Assuming that both kidneys were potentially suitable for transplantation, this highlights conflicting viewpoints on the suitability of ECD/DCD kidneys for transplantation by different transplant clinicians. Among the recipients of these single kidneys, graft failure (i.e., need for chronic dialysis or pre-emptive retransplantation) was from primary nonfunction, which has been well documented to occur more frequently among recipients of DCD kidneys (17). Interestingly, the remaining graft losses occurred because of death with graft function (i.e., there were no death–censored graft losses in the follow-up period), and compared with recipients of ECD/DCD kidneys from donors with both kidneys used for transplantation, the cumulative incidence of total graft failure was slightly higher. However, this may be a function of the higher baseline hazard of death in recipients selected to receive these kidneys, because clinicians may preferentially allocate these kidneys to candidates with an increased probability of death on the waiting list. This highlights the importance of determining the survival benefit of ECD/DCD kidney transplantation versus remaining on the waiting list.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the rate and determinants of discard of ECD/DCD kidneys. Although the sample size is small, the donors included in this study represent the largest pool of ECD/DCD kidneys available for study to date. Furthermore, we included in our analysis the majority of the donor characteristics that are available to clinicians at the time of a kidney offer, and we used the KDRI to quantify donor quality.

Despite these notable strengths, our study has some limitations. First, the actual reason for discard of ECD/DCD kidneys is unknown. Although the decision to discard a kidney may have been because of donor characteristics that were evaluated in this study, other factors that are not completely captured in the registry, such as PMP parameters or kidney biopsy findings, may have also influenced their use or nonuse. Second, the decision-making process of the transplant clinician when faced with an ECD/DCD kidney offer is not captured, and therefore, it is not possible to determine clinicians’ attitudes toward ECD/DCD kidneys. Third, although we statistically accounted for the tendency of discarding ECD/DCD kidneys to cluster by transplant center, we did not have data to evaluate the determinants of discard at the level of the providers, hospitals, and/or organ procurement organizations. Fourth, although the SRTR captures all discarded and transplanted kidneys in the United States, our analysis is limited by the scope of the data elements within the registry. In our study, both the insufficient capture (i.e., missing kidney biopsy results) and the absence of data (i.e., reason for organ discard) are examples of important elements that may be driving clinical decision making. Fifth, it is important to note that this study examined discard rates in the United States exclusively. Given the differences in discard rates that exist between countries (Supplemental Table 1) (18,19), variation in use and nonuse of ECD/DCD kidneys by country is also likely to occur.

In summary, this study shows that there is a significant overlap in KDRI scores among ECD/DCD kidneys that are discarded versus used. This suggests that there may be a significant number of discarded ECD/DCD kidneys that may be acceptable for transplantation. Given the ongoing shortage of kidneys for transplantation, the use of carefully selected ECD/DCD kidneys may be an appropriate strategy to expand the deceased donor pool. Although the KDRI is an imperfect measure of donor quality, ECD/DCD kidneys with KDRI values below the national median for previously transplanted ECD/DCD kidneys should be given due consideration for use, especially in patient populations at increased risk for adverse outcomes on chronic dialysis. Because the number of ECD/DCD donors is likely to increase in the future, we sought to describe the use patterns of ECD/DCD kidneys to increase awareness of discard rates and start to better understand how to optimally select these kidneys for transplantation. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the specific factors that influence clinical decision making around the use of ECD/DCD kidneys as well as physicians’ attitudes toward ECD/DCD kidney offers. In particular, the reasons for discard or nonrecovery of kidneys are important data elements that should be captured in national registries. Moreover, there is a need to evaluate the potential survival benefit of using ECD/DCD kidneys for transplantation versus remaining on the waiting list for a non–ECD and/or non–DCD kidney to better inform patients about the risk-benefit tradeoff of receiving these kidneys.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR).

This work has been previously presented in abstract form at the World Transplant Congress (San Francisco, CA) on July 28th, 2014.

The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07190715/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N: A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int 50: 235–242, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Renal Data System: Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Institute for Health Information : Canadian Organ Replacement Register Annual Report. Treatment of End-Stage Organ Failure in Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada, Canadian Institute of Health Sciences, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snoeijs MG, Winkens B, Heemskerk MB, Hoitsma AJ, Christiaans MH, Buurman WA, van Heurn LW: Kidney transplantation from donors after cardiac death: A 25-year experience. Transplantation 90: 1106–1112, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sung RS, Christensen LL, Leichtman AB, Greenstein SM, Distant DA, Wynn JJ, Stegall MD, Delmonico FL, Port FK: Determinants of discard of expanded criteria donor kidneys: Impact of biopsy and machine perfusion. Am J Transplant 8: 783–792, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh SK, Kim SJ: Does expanded criteria donor status modify the outcomes of kidney transplantation from donors after cardiac death? Am J Transplant 13: 329–336, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, Andreoni KA, Wolfe RA, Merion RM, Port FK, Sung RS: A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: The kidney donor risk index. Transplantation 88: 231–236, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, Distant DA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Metzger RA, Ojo AO, Port FK: Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA 294: 2726–2733, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojo AO, Hanson JA, Meier-Kriesche H, Okechukwu CN, Wolfe RA, Leichtman AB, Agodoa LY, Kaplan B, Port FK: Survival in recipients of marginal cadaveric donor kidneys compared with other recipients and wait-listed transplant candidates. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 589–597, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodside KJ, Merion RM, Leichtman AB, de los Santos R, Arrington CJ, Rao PS, Sung RS: Utilization of kidneys with similar kidney donor risk index values from standard versus expanded criteria donors. Am J Transplant 12: 2106–2114, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein AS, Messersmith EE, Ratner LE, Kochik R, Baliga PK, Ojo AO: Organ donation and utilization in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant 10: 973–986, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirth RA, Pan Q, Schaubel DE, Merion RM: Efficient utilization of the expanded criteria donor (ECD) deceased donor kidney pool: An analysis of the effect of labeling. Am J Transplant 10: 304–309, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schold JD, Kaplan B, Baliga RS, Meier-Kriesche HU: The broad spectrum of quality in deceased donor kidneys. Am J Transplant 5: 757–765, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summers DM, Johnson RJ, Hudson A, Collett D, Watson CJ, Bradley JA: Effect of donor age and cold storage time on outcome in recipients of kidneys donated after circulatory death in the UK: A cohort study. Lancet 381: 727–734, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locke JE, Segev DL, Warren DS, Dominici F, Simpkins CE, Montgomery RA: Outcomes of kidneys from donors after cardiac death: Implications for allocation and preservation. Am J Transplant 7: 1797–1807, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber M, Dindo D, Demartines N, Ambühl PM, Clavien PA: Kidney transplantation from donors without a heartbeat. N Engl J Med 347: 248–255, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ANZOD Registry: ANZOD Registry Report: Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation Registry, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callaghan CJ, Harper SJ, Saeb-Parsy K, Hudson A, Gibbs P, Watson CJ, Praseedom RK, Butler AJ, Pettigrew GJ, Bradley JA: The discard of deceased donor kidneys in the UK. Clin Transplant 28: 345–353, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.